Abstract

Objectives

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and insomnia symptoms are often found to occur together. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between sleep and IBS complaints, and their impact on reported health and daytime functioning.

Methods

An online advertisement invited people with difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep to participate in an online survey. Sleep characteristics were assessed and the Birmingham IBS Symptoms Questionnaire was completed, including subscales on IBS-related constipation, pain, and diarrhoea. Perceived immune functioning and general health were self-rated and the lapses subscale of the Manchester Driver Behaviour Questionnaire was completed as a proxy of daytime functioning.

Results

Significant associations were found between sleep symptoms and IBS-related constipation, pain, and diarrhoea reports. Most sleep variables were negatively affected in subjects reporting IBS complaints, as reflected in patients reporting poorer sleep quality and less satisfaction with their sleep pattern. The associations with sleep difficulties were most pronounced for IBS-related pain. Being a woman, of younger age, and having an insomnia diagnosis were factors that were associated with having significantly more severe IBS symptoms. The association with IBS was significant for the severity of difficulty falling asleep, but not for the severity of difficulty maintaining sleep.

Conclusion

There is a clear relationship between sleep, perceived health, and IBS complaints. The association with IBS complaints was significant for difficulty falling asleep, but not for difficulty maintaining sleep, which may have implications for the combined treatment of sleep difficulties and IBS-related pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is defined by the ROME IV criteria as a functional bowel disorder, characterised by recurrent abdominal pain associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits [1]. The abdominal pain is accompanied by diarrhoea or constipation, or both. IBS symptoms should be present for at least 1 day per week during the past 3 months, with a symptom onset of at least 6 months before the diagnosis is made [1]. IBS complaints are related to changes in mucosal barrier integrity and secretion which causes an increased sensitivity of the bowel and changed bowel motility. Several psychological and physiological stressors may impact the severity of IBS complaints [2,3,4], including comorbid disorders such as insomnia [5]. Insomnia is diagnosed in 10–20% of adults and is defined by difficulty falling asleep, maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, or poor sleep quality (i.e., non-restorative sleep) [6, 7]. Both IBS and insomnia have been associated with daytime impairment and distress, and reduced quality of life [5, 8].

IBS is often associated with disturbed and insufficient sleep [5, 9, 10]. On the one hand, for example, Lee et al. reported that total sleep time (TST), sleep onset latency (SOL), difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep, and the number of awakenings at night relate to the severity of IBS symptoms [10]. On the other hand, IBS complaints, in particular pain, often have a significant impact on sleep. Therefore, the association between IBS and insomnia is of a bi-directional nature. In a recent study, the association between sleep complaints and IBS was investigated among 1950 Dutch students [5]. The analysis revealed that IBS symptoms severity was significantly associated with the severity of insomnia symptoms, sleep quality, sleep onset latency, and number of nightly awakenings. Having IBS complaints was negatively correlated with perceived general health, perceived immune functioning, and quality of life. However, the data were collected from a relative young and healthy population and most participants did not screen positive for having insomnia. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to specifically recruit adult subjects with sleep difficulties to further investigate the association between IBS and sleep. As both insomnia and IBS are heterogeneous conditions, it was determined whether the nature and extent of sleep difficulties (i.e., sleep initiation problems, sleep maintenance problems, or both) had a differential impact on specific IBS complaints (constipation, pain, or diarrhoea). The impact of gender and having a formal insomnia diagnosis on experiencing IBS complaints was also evaluated. Finally, disturbed sleep and IBS complaints were related to health perception and their impact on daytime functioning was assessed by investigating to what extent these complaints affect driving ability.

2 Methods

In February 2018, subjects, aged 18 and older, were invited via a Facebook advertisement to complete an online survey, created in Survey Monkey. The advertisement specifically targeted subjects ‘having difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep (insomnia)’. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences of Utrecht University approved the study. As an incentive to participate, subjects could enter a prize draw to win a pillow. Data were stored anonymous (personal data, i.e., email addresses were removed from the dataset).

The survey first gathered information on demographics. These were followed by a series of questions about the nature and extent of sleep problems (i.e., sleep initiation problems, sleep maintenance problems, or both), IBS complaints (constipation, pain or diarrhoea), health perception (self-rated general health and immune functioning), and daytime functioning (lapses during driving).

2.1 Sleep Complaints

Data were collected on the type and duration of sleep disturbances and whether or not the insomnia was formally diagnosed. The severity of sleep difficulties was assessed for ‘difficulty falling asleep’ and ‘difficulty maintaining sleep’ on a scale ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (very). To calculate total sleep time and sleep onset latency, information on common sleep characteristics was collected using items from the Groningen Sleep Quality Scale (GSQS) [11]. Perceived ‘sleep quality’ and ‘satisfaction with sleep pattern’ were scored on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (very poor) to 10 (excellent).

2.2 IBS Complaints

The presence and severity of IBS symptoms were evaluated with a modified Dutch version of the Birmingham IBS Symptom Questionnaire [12]. The questionnaire comprises 11 items with 6-answer possibilities, ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). The sum-score of all items represents overall IBS symptom severity and higher scores indicate a greater likelihood of diagnosis of IBS. In addition, scores on three symptom-specific scales representing the factors ‘constipation’ (three items), ‘pain’ (three items), and ‘diarrhoea’ (five items) were calculated.

2.3 Perceived Health Status and Immune Functioning

Self-rated current immune functioning and perceived general health were assessed using single-item questions and rated on a scale ranging from 0 (very poor) to 10 (excellent) [13]. Past-year immune status was assessed with the Immune Status Questionnaire (ISQ) [14]. The ISQ is a 7-item scale assessing the frequency of experiencing sudden high fever, diarrhoea, headache, skin problems, muscle and joint pain, common cold, and coughing, on a scale ranging from never (0), sometimes (1), regularly (2), often (3) to (almost) always (4). The total ISQ score ranges from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating a poorer past year’s immune fitness.

2.4 Daytime Functioning—Driving

As a measure of daytime functioning that may be affected by disturbed sleep, the Dutch version of the lapses subscale of the Manchester Driver Behaviour Questionnaire was completed [15]. The lapses subscale consists of eight items that can be rated on a six-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (nearly all the time). Lapses are defined as brief periods of inattention and reduced alertness, which may be a risk factor for car crashes [16, 17]. Higher scores indicate more lapses.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS statistics, version 25). Bivariate correlations between the IBS scores and the variables were calculated using the Spearman’s ρ correlation coefficient for non-parametric data and the Pearson’s r correlation coefficient for parametric data. In particular, analyses were conducted to compare (1) men and women, (2) those with and without a formal insomnia diagnosis, and (3) those with sleep initiation problems, sleep maintenance problems, or both. The groups were compared using ANOVA in case of a normal distribution, and the nonparametric Independent Samples Mann–Whitney U test was applied if the data were not normally distributed.

3 Results

Of the N = 1031 subjects who opened the link to the survey, N = 25 were excluded from the study as they did not accept the terms and conditions of the survey; another N = 41 were excluded as they did not present with sleep problems; and N = 94 were excluded because their data were unreliable or incomplete (i.e., who stopped the survey before completing questions on sleep and IBS). Data from N = 871 subjects, of which N = 698 (83.1%) women, were included in the analysis. The mean (SD) age of the study cohort was 37.0 (13.3) years and their mean (SD) BMI was 26.6 (5.6) kg/m2. As sometimes subjects skipped answering some of the questions of the survey, the total number of participants varies between the different correlations, as indicated in tables.

Table 1 gives an overview of associations between sleep and IBS variables. It shows that various sleep difficulties correlate significantly, albeit modestly, with the overall IBS severity and the subscales for constipation, pain, and diarrhoea. Of note, there were significant correlations between IBS complaint severity and difficulty falling asleep, but not for difficulty maintaining sleep. The duration of sleep problems was not significantly associated with the severity of IBS complaints. Amongst the various IBS symptoms, the correlations were strongest with IBS-related pain. In addition, IBS severity correlated significantly with self-rated general health and immune functioning. Finally, driving impairment, operationalized as lapses during driving, correlated significantly with the severity of IBS complaints (overall, and the three subscales).

Table 2 presents the correlations calculated for men and women separately. The correlation in women was generally more robust than those observed in men. In fact, the associations between sleep variables and IBS complaints among men often did not reach statistical significance. Women had significantly higher scores on difficulty to falling asleep, reported a significantly higher number of nightly awakenings, and had a significantly higher BMI relative to men.

Table 3 compares subjects diagnosed as having insomnia with subjects that did not have this diagnosis. Subjects with an insomnia diagnosis reported significantly more severe sleep disturbances, as well as significantly more severe IBS symptoms. The correlations between sleep and IBS complaints in diagnosed patients were stronger than those observed in subjects without an insomnia diagnosis.

Subjects with difficulty falling asleep had significantly less nightly awakenings and were younger than subjects with sleep maintenance difficulties. The groups did not significantly differ on other sleep outcome measures. Subjects that reported having both sleep initiation and maintenance complaints experienced sleep problems for a significantly longer duration, had a shorter total sleep time, more nightly awakenings, and were accordingly less satisfied with their sleep and sleep quality than subjects with only one of the sleep symptoms. As expected, they rated their general health and perceived immune functioning as lower than those who reported only one sleep complaint. The association with IBS complaints was significant for the severity of difficulty falling asleep, but not for the severity of difficulty maintaining sleep (see Table 4).

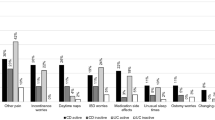

Finally, the association of current immune functioning and past year’s immune fitness with sleep and IBS outcomes was investigated. The results are summarised in Fig. 1. Perceived current immune functioning (Fig. 1, top) correlated significantly with the total IBS score, and the subscales for constipation, diarrhoea, and pain (p < 0.0001). For sleep outcomes, perceived immune functioning correlated significantly with sleep quality (p = 0.0001) and the number of nightly awakenings (p = 0.004), but not with TST (p = 0.127). In accordance, past year’s immune fitness (Fig. 1, bottom) correlated significantly with the total IBS score, and the subscales for constipation, diarrhoea, and pain (p < 0.0001). For sleep outcomes, ISQ scores correlated significantly with sleep quality (p = 0.0001) and the number of nightly awakenings (p = 0.037), but not with TST (p = 0.392).

Associations between sleep, immune functioning, and IBS. Significant associations (p < 0.05) are depicted as uninterrupted lines. Note: in the top figure, current immune functioning was rated from 0 (poor) to 10 (excellent), resulting in negative correlations with sleep and IBS complaints. In the bottom figure, past year’s immune fitness was assessed with the ISQ in which higher scores represent poorer immune fitness, resulting in positive correlations with sleep and IBS outcomes

4 Discussion

The current study in adults with insomnia and or disturbed sleep (induction and or maintenance) showed that sleep is negatively associated with the presence of IBS. This is reflected in patients reporting poorer sleep quality and less satisfaction with their sleep pattern. The associations were most pronounced for the IBS subscale of pain, which is consistent with the previous research [5]. Disturbed or insufficient sleep for any cause exacerbates pain. This finding suggests that the improving sleep behaviourally and/or pharmacologically will reduce IBS-associated pain. Further, these data show that having IBS complaints is associated with the severity of difficulty falling asleep, but not with the severity of difficulty maintaining sleep. This finding suggests that the most important therapeutic approach would be behavioural treatment intended to reduce sleep latency (e.g., relaxation training) or pharmacological intervention with hypnotic agents with short sleep latency. Future research is needed to determine if there is a phase delay among IBS patients given their difficulty falling asleep. If so, the use of light to phase advance IBS patients might relieve the sleep impairments as well as the pain associated with it.

While sleep initiation seems to be the dominant problem, it is important to recognise that sleep difficulties were worst in the group that reported having both difficulty falling asleep and sleep maintenance problems (see Table 4). In terms of IBS, these are the subjects that reported significantly higher scores on overall IBS complaints, and more specific IBS pain complaints, compared to subjects who only reported sleep maintenance problems. The association between IBS complaints and sleep difficulties is further supported by the comparison of diagnosed insomnia relative to non-diagnosed patients. The associations with IBS complaints were greater in subjects with a formal insomnia diagnosis and those using sleep medication. These patients report significantly more severe sleep disturbances, as well as significantly more severe IBS symptoms compared to subjects with no formal insomnia diagnosis. These findings may reflect the fact that subjects with more severe complaints are more likely to visit their physician and inquire for treatment.

IBS is a chronic disorder that is present in all age groups. However, older people tend to have milder symptoms than younger IBS patients [18, 19]. Consistent is that data of the current study found significant negative correlations between age and the severity of IBS complaints. This might be explained by the fact that older people become more tolerant to IBS symptoms over time. A paradoxical finding is that sleep disturbance aggravates with age while IBS symptoms seem to moderate with age. This seeming discrepancy might in fact be explained by the fact that IBS is related primarily to sleep induction and the primary sleep difficulty in the elderly is sleep maintenance.

IBS and insomnia occur more often in women than in men [8], and in line, in the current study, the observed correlations between IBS and sleep were stronger in women compared to men. Women also had significantly higher absolute scores on the IBS subscales. Thus, both sleep disturbances and IBS complaints were more frequently reported and more severe in women compared to men. This observation has been reported previously by Lee et al. who argued that sex differences in both autonomic and attentional processes may facilitate sex-specific general stress responses that may also affect the presence and severity of IBS complaints [20].

The associations between IBS and sleep complaints have clear implications for quality of life and the performance of daily activities. Also, in the current study, significant associations were observed indicating that subjects with more IBS and/or sleep complaints report poorer general health and reported poorer immune functioning. As an example of a daily activity, effects on driving performance were operationalized by assessing lapses during driving. In women with an increasing severity of IBS symptoms, significantly more lapses were reported. In men, the correlations between IBS complaints and lapses were not significant.

Previous studies showed that perceived health and immune status are associated with both sleep quality and insomnia complaints [21], and IBS complaints [5]. Donner et al. [21] reported significant associations between sleep complaints and perceived immune functioning, whereas Balikji et al. [5] found significant associations between IBS symptom severity and insomnia complaints (r = 0.32, p = 0.0001), sleep quality (r = − 0.21, p = 0.0001), sleep onset latency (r = 0.11, p = 0.0001) and the number of nightly awakenings (r = 0.24, p = 0.0001). Similar associations were found in the current study, confirming that significant associations were found between IBS and sleep outcomes (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). In addition, both sleep and IBS outcomes correlated significantly with current perceived immune functioning and past year’s immune fitness (see Fig. 1). Correlations were most strong in men, subjects formally diagnosed with insomnia, and those who report having both sleep initiation and sleep maintenance problems (see Tables 2, 3, 4). Together, the observed multiple significant interrelationships further support the growing evidence that the immune system is involved in the pathogenesis of both insomnia and IBS.

The current findings suggest that people with IBS complaints can significantly improve their IBS-related health status by improving their sleep. The data suggest that, in this context, a focus on sleep initiation problems would be most effective. This may be accomplished by adopting adequate sleep practices, but they may also benefit from behavioural as well as pharmacological treatment of insomnia.

Several limitations have to be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, the current study consists of a relatively young study population. Since the subjects were recruited via Facebook, this has limited the number of elderly who participated, as they less frequently use social media and computers than younger adults. Therefore, it is not clear how the current findings can be translated to older age groups, which limits the generalizability to the population at large. Second, the current study population consisted of relatively more women (83.1%) than men, reflecting the higher prevalence of IBS and sleep disturbance in women than men [8, 22]. However, the study population was sufficiently large for conducting statistical analyses for both sexes. Third, the data of our study were assessed solely by self-report. Recall bias, thus, may have influenced the outcome. Biomarkers of IBS, objective measurement of pain sensitivity, and objective assessments of sleep such as polysomnography should be implemented in future studies to verify the observed relationships.

Taken together, the current findings underline the associations between sleep, perceived health, and IBS complaints. Sleep complaints can exacerbate IBS complaints, and vice versa. Given this, the data suggest that a combined treatment of insomnia and IBS complaints should be most effective.

References

Lacy BE, Maerin F, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1393–407.

Drossman A. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and ROME IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1262–79.

Boeckxstaens G, Camilleri M, Sifrim D, Houghton LA, Eisenbruck S, Lindberg G, Azpiroz F, Parkman HP. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: physiology/mobility—sensation. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1292–304.

Vanner SJ, Greenwood-van Meerveld B, Mawe GM, Shea-Donohue T, Verdu EF, Wood J, Grundy D. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: basic science. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1280–91.

Balikji S, Mackus M, Brookhuis K, Garssen J, Kraneveld AD, Roth T, Verster JC. The association of sleep, perceived immune functioning, and irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2018;7:238.

Cao XL, Wang SB, Zhong BL, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Li L, Chiu HF, Lok GK, Lu JP, Jia FJ, Xiang YT. The prevalence of insomnia in the general population in China: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170772.

Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2016;165(2):125–33.

Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7–10.

Goldsmith G, Levin JS. Effect of sleep quality on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Digest Dis Sci. 1993;38:1809–14.

Lee SK, Yoon DW, Lee S, Kim J, Choi K-M, Shin C. The association between irritable bowel syndrome and the coexistence of depression and insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2017;2017(93):1–5.

van der Mulder-Hajonides Meulen WREH, Wijnberg JR, Hollander JJ, De Diana IPF, van den Hoofdakker RH. Measurement of subjective sleep quality. Eur Sleep Res Soc Abstr. 1980;5:98.

Roalfe AK, Roberts LM, Wilson S. Evaluation of the Birmingham IBS symptom questionnaire. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:30.

Van Lantman Schrojenstein M, Otten LS, Mackus M, de Kruijff D, van de Loo AJAE, Kraneveld AD, Garssen J, Verster JC. Mental resilience, perceived immune functioning, and health. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:107–12.

Van de Loo AJAE, Wilod Versprille LJF, Mackus M, Kraneveld AD, Garssen J, Verster JC. Development of the Immune Status Questionnaire (ISQ). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(Supplement 1):S300.

Lajunen T, Parker D, Summala H. The Manchester Driver Behaviour Questionnaire: a cross-cultural study. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36:231–8.

Parker D, McDonald L, Rabbitt P, Sutcliffe P. Elderly drivers and their accidents: the Aging Driver Questionnaire. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32:751–7599.

Verster JC, Bervoets AC, de Klerk S, Roth T. Lapses of attention as outcome measure of the on-the-road driving test. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:283–92.

Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;46:71–80.

Tang YR, Yang WW, Liang ML, Xu XY, Wang MF, Lin L. Age-related symptom and life quality changes in women with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7175–8.

Lee OY, Mayer EA, Schmulson M, Chang L, Naliboff B. Gender-related differences in IBS symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;21:84–93.

Donners AAMT, Tromp MDP, Garssen J, Roth T, Verster JC. Perceived immune status and sleep: a survey among Dutch students. Sleep Disord. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/721607.

Chang L, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1686–701.

Funding

This study was supported by Utrecht University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Thomas Roth has received Grants/research support from Aventis, Cephalon, Glaxo Smith Kline, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Wyeth and Xenoport and has acted as a consultant for Abbott, Acadia, Acoglix, Actelion, Alchemers, Alza, Ancil, Arena, Astra Zeneca, Aventis, AVER, BMS, BTG, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, Elan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, Glaxo Smith Kline, Hypnion, Impax, Intec, Intra-Cellular, Jazz, Johnson & Johnson, King, Lundbeck, McNeil, Medici Nova, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Orexo, Organon, Prestwick, Procter-Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Resteva, Roche, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Vanda, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport. Joris Verster has received Grants/research support from the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment, Janssen, Nutricia, Red Bull, Sequential, and Takeda, and has acted as a consultant for the Canadian Beverage Association, Centraal Bureau Drogisterijbedrijven, Clinilabs, Coleman Frost, Danone, Deenox, Eisai, Janssen, Jazz, More Labs, Purdue, Red Bull, Sanofi-Aventis, Sen-Jam Pharmaceutical, Sepracor, Takeda, Toast!, Transcept, Trimbos Institute, Vital Beverages, and ZBiotics. The other authors have not potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences of Utrecht University approved the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdulahad, S., Huls, H., Balikji, S. et al. Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Immune Fitness, and Insomnia: Results from an Online Survey Among People Reporting Sleep Complaints. Sleep Vigilance 3, 121–129 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-019-00066-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41782-019-00066-4