Abstract

Recent research has considered the contribution of faith-based actors (FBAs) and religious norms to global sustainability and climate governance. However, as yet, it has paid little attention to the relationship between religion and climate politics in the EU. The EU is supposedly a secular body. Nevertheless, FBAs participate in its climate policy discourse, and, therefore, their normative contributions are of interest. In this article, therefore, we explore the role of FBAs in the EU climate discourse with respect to two specific questions: what, if any, specific normative arguments and claims do the FBAs contribute to the EU’s climate policy discourse; and, can or do the relevant normative arguments and claims serve as a basis for collaboration or are they a source of normative conflict between different FBAs or between FBAs and non-FBAs? To answer these questions, we draw on the EU’s transparency register and a content analysis of a specific dialogue between FBAs and the EU’s institutions. On this basis, we identified a range of active FBAs within EU climate politics and demonstrated that they contribute to the European climate discourse by adding deep-rooted values. One way this is achieved is through the connection of climate values to “creation” and the divine command to mankind which can give specific meaning to one’s understanding of nature and fellow humans, as well as one’s sense of responsibility towards both. Furthermore, we find a basis for both agreement and conflict in references to religious norms and ideas. Many actors from different faiths and secular backgrounds emphasize the compatibility of faith-based and other norms. However, other actors highlight differences in perspectives and challenges to climate governance that arise from “conservative” religious norms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Faith-based actors (FBAs) are increasingly pursuing ambitious goals in international climate policy. They participate in climate-related political discourses and engage in policy events that focus on climate change governance. Prominent examples of FBA engagement with these issues include the papal encyclical “Laudato Si’” and the “Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change,” which were both published before the Paris climate summit in 2015 (Abdellah 2020; Reuber and Fuchs 2019). Scholars have also documented attempts by FBAs to generate joint statements and initiate activities that specifically promote a religious approach to sustainability at the United Nations (UN) climate summits (Glaab 2017).

However, what is the situation in the EU? Currently, the European Green Deal represents an apparent attempt to establish a supranational policy to address global warming. However, as with the UN, the European institutions also offer civil society organizations institutionalized venues for participating in policy discourse and development—after all, the EU is, as a community of countries, seen as a primarily secular entity (Casanova 2019; v. Sass 2019; Berger 1999; Lehmann 2007). Furthermore, it is made up of increasingly pluralistic societies and is thus faced with the challenge of striking agreements that integrate different points of view and that are considered legitimate from different perspectives. Therefore, it is interesting to inquire into the potential contribution FBAs could make to the EU’s climate policy discourse. Who represents religious interests in the European climate policy discourse? What specific normative contributions do the FBAs make here? Do these ideas have common ground, and thus reveal an ability to strengthen religion’s potential to contribute to climate governance or does normative conflict prevail? What is the situation between FBAs and non-faith-based civil society actors in this respect? After all, research has highlighted that the use of religious content in politics can evoke value conflicts and division between FBAs and between FBAs and other actors (Willems 2007). Indeed, the view of religion as a source of conflict used to dominate entire research fields (Huntington 1996).

Analysing the potential of FBAs to contribute to the European climate policy discourse does not mean that we are simply assuming a general greening of and through religion. Religious ideas, including ideas about humankind’s dominion over nature or the “prosperity gospel,” have been and continue to be regularly used to promote and defend unsustainable practices (Carr et al. 2012; McCammack 2007; White 1967; Wilson and Steger 2013). Moreover, the seriousness of religiously motivated climate activism can also be questioned in relation to actual investments in energy savings and renewable energy sources on the ground, i.e. in the local religious communities (Kommission Weltkirche der Deutschen Bischofskonferenz 2021). Nevertheless, Tucker and Grim (2001) stress that most religions today advocate for climate protection and sustainability. Likewise, many other researchers have documented a number of relevant actions undertaken by FBAs in international governance (Baumgart-Ochse and Wolf 2019; Haynes 2013; Glaab 2014, 2017; Glaab and Fuchs 2018).

Acknowledging the potential contribution and the past and present challenges to climate governance that are related to religious actors and religious thought, this article inquires into the normative contribution FBAs can potentially make to European climate policy discourse using the example of one specific dialogue between FBAs and the EU’s institutions. Scholars and practitioners have highlighted that changes in norms and values are a necessary condition for a successful sustainability transformation. Given this need, the potential contribution of FBAs deserves particular attention as norms and values are at the core of their activities. At the same time, religious ideas may conflict with each other. Indeed, religious ideas not only cause conflict between different religions but also within religions. Thus, our analysis aims to identify the positions of specific FBAs as well as the normative agreements and disagreements between themselves and between the FBAs and other actors within the dialogue.

We use the term faith-based actor as a description of institutionalized non-governmental organizations that are, according to their declaration, based on religious values and/or traditions. In so doing, we adopt a definition that is prevalent in the political science literature (e.g., Democratic Progress Institute 2012; Berger 2003; Haynes 2014). As they are most visible through their participation in political arenas, we focus specifically on organized actors who manifest a faith-based self-identification in their name or motivation (as, for instance, indicated on their website).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The following section lays out the institutional context and norm-based focus of our inquiry. Subsequently, we detail our methodological approach in terms of identifying relevant actors and analysing the dialogue. We then present our empirical findings before summarizing our article and discussing the implications for research and policy in the concluding paragraph.

2 FBAs and religious norms at the EU

Quite a bit of research has addressed the role of religious actors in international governance today (Baumgart-Ochse and Wolf 2019). Scholars have examined the role of FBAs in peace and conflict, development, health, and human rights, for instance (Bercovitch and Kadayifci-Orellana 2009; Carrette and Miall 2017; Beinlich 2019; Clarke 2019; Coni-Zimmermann and Perov 2019). They have also paid considerable attention to the role of FBAs in sustainability governance, concerning both ecological and social sustainability (Glaab et al. 2019). This research has documented the specific normative contributions of FBAs to sustainability governance at the United Nations. For example, Glaab and Fuchs (2018) identified the use of a more comprehensive definition of sustainability and wellbeing in FBAs’ submissions to the Rio +20 summit. They also showed that FBAs tend to use less utilitarian and technocratic arguments than other civil society actors, emphasizing moral norms and spiritual values. However, this does not mean that religious actors promote religious views, in a narrow sense, in international policy discourse. Haynes (2013), for instance, highlighted that FBAs tend to employ secular language in order to be heard and accepted at the UN, while Glaab and Fuchs (2018) found strategic variance in FBAs’ reference to secular or religious norms.

Such understanding of the specific role of FBAs in sustainability and climate governance within the EU is still missing. This may be due to the EU’s reputation as a secular realm of governance. However, as Habermas (2008, 2011) asserted, religion still has a specific potential in modern societies, primarily in motivational and ethical regards. He argues that religious actors and norms may add references to values and deeper meaning to an otherwise (supposedly) rational discourse and that they may offer answers to societal problems that are not or only insufficiently provided by other norms and ideas. Likewise, Morrison et al. (2015) argue, in line with Posas (2007), that religions could add an ethical dimension to the climate discourse and, therefore, encourage their members to that purpose. Sachdeva (2016) also underlines that religious values may have a more profound impact on human identity and behaviour than secular incentives.

Indeed, an institutionalized avenue for FBA participation in EU governance does exist. In general, the EU’s institutions are open for contributions from all sectors of society. Article 11 of the treaty of the European Union calls specifically for “an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society.” Institutionalized dialogues have, for example, the purpose of facilitating a regular, transparent, and open exchange between the EU’s institutions and organized civil society around socially relevant topics such as migration and human rights.

FBAs have access to EU governance, in particular, through the regular high-level meetings between representatives of the EU institutions, religious communities and philosophical and non-confessional humanist organizations. Both the European Parliament and the European Commission assign responsibility for these dialogues to one of their vice presidents. With these high-level talks, the EU institutions attempt to integrate the diverse religious voices from within the EU into the policy discourse. Although the EU is perceived as mostly secularized, the meetings show that there is room within the institutionalised processes for religious views and exchange. Indeed, the Maastricht Treaty and, even more so, the Treaty of Lisbon structured and intensified relations between the EU institutions and religious organizations. While FBA engagement in EU governance was rare at the beginning of the European integration process, many FBAs maintain offices in Brussels and participate in various fields of EU governance, today (Liedhegener 2013; Leustean 2013). Accordingly, the question of the normative contributions of FBAs to EU climate governance is a relevant one to ask.

We approach norms using the constructivist approach to norms that is prevalent in the international relations literature. According to this literature, norms can be defined as “[…] standards of appropriate behaviour of an actor […]” (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998, p. 891) or “[…] intersubjective understandings that constitute actors’ interests and identities, and create expectations as well as prescribe what appropriate behavior ought to be” (Björkdahl 2002, p. 21). From this constructivist point of view, norms include both constitutive and constraining aspects. They bring categories into being (e.g., categories of actors or actions) while also limiting action and defining what is perceived as legitimate. Thereby, norms reflect intersubjectively shared understandings and ascribe values to material and immaterial objects (Wiener 2008). When examining norms, we pay attention to what they say about a problem, value, and action (Winston 2018). The problem aspect of a norm identifies the relevant context and issues to be addressed. This may include obstacles, reasons, and outcomes that should be rectified. The value aspect is defined as beliefs that give meaning to action or situations and give people orientation in their surroundings (Hitlin and Piliavin 2004). Values can give moral weight to problems and actions. Finally, the action aspect of a norm describes what is supposed to be done and may represent the proposed solution for tackling a given problem. The action puts the value of the norm into practice (Winston 2018; Carpenter 2007).

Importantly, norms are not as static as theorizing may suppose. They have a “dual nature” (Wiener 2007), which means that they are both stable and flexible at the same time. Norms exist in a particular form at any given point in time but constantly evolve in between. Actors are constrained by norms but also shape them. In fact, every reference to a norm also likely brings about a change in its substance—even if that change is ever so slight (Graf 2016).

In line with this constructivist approach towards norms, we can also examine how actors construct and shape dynamics between norms. Through discursive acts connecting different norms, actors can attribute a broad range of meanings. This agency can target positive forms of norm interplay (e.g., connections between norms or additions) as well as negative forms (e.g., competition or conflict), thus broadening or limiting the scope, validity, and application of specific norms (Fehl and Rosert 2020).

In our inquiry, we concentrate on references to religious norms by FBAs and other actors. This includes norms that can be identified as religious in a narrow sense in that they entail a reference to transcendence. It also includes broader norms, such as “justice”, which FBAs tend to link to their normative traditions and beliefs but which are just as likely to be referenced by non-FBA actors.

For the analysis of agreement or conflict, we focus on norm relations and dynamics between different norms or aspects of norms as guided by Fehl and Rosert (2020), who differentiate between synergetic and conflicting norms. Both types of norm relation describe the interplay of two norms with similar thematic, timely and social overlap but also with divergences in the norm content (problem, value, action). Fehl and Rosert argue that conflicting norm relations tend to occur between norms with different definitions of underlying problems and/or actions. In contrast, norms with similar descriptions of problems and actions but different values often facilitate synergies between norms.

In sum, we expect to find that FBAs engage in the EU climate policy discourse with normative arguments, drawing more or less explicitly on religious norms. We are also interested in identifying discursive acts that establish common ground between faiths and other sectors of society or draw out differences. Thereby, we hope to identify the potential for collaboration and conflict related to religious actors’ roles and arguments in climate governance.

3 Data and method

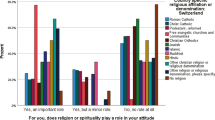

In the course of our analysis, we conducted two separate investigations. First, we identified FBAs active in European Climate Governance using the European transparency register.Footnote 1 The register, which is accessible online, provides filtering options for different types of actors (e.g., professional consultancies, in-house lobbyists, non-governmental organizations) and fields of interest, allowing us to measure the presence and distribution of FBAs in European climate governance. To identify the FBAs that work on topics related to climate politics, we built a subset of the transparency register, integrating all actors with a religious affiliation in their corporate name or motivation and who indicated an interest in the topic “climate action.” Actors who register in the transparency register can sort themselves into their relevant sections. We included most actors from the section “Organisations representing churches and religious communities” (not including humanist organizations) and also integrated FBAs from the section “Non-governmental organisations”. We then categorized the resulting list of actors by religious affiliation, which we identified through the actors’ websites.

Secondly, in order to investigate the specific contributions FBAs bring into the climate politics’ discourse and their potential for normative agreement or conflict, we qualitatively analysed the transcript of a dialogue meeting between FBAs, representatives of the European institutions, and other actors. The dialogue was organized in January 2020 by the European Parliament under the title “The European Green Deal: Preserving our Common Home”. It brought together representatives from Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, and Humanist organizations as well as scientific and political representatives from the European Parliament and the European Commission. An audience also attended the sessions. The dialogue consisted of statements presented by the panellists, a debate between the panellists, and questions and comments from a larger audience. The meeting was recorded and the video was released on the European Parliament’s website.Footnote 2 We transcripted it and to evaluate it, we conducted a computer-assisted qualitative content analysis following the rule-bound procedure outlined by Mayring (2014). The process is appropriate for handling large amounts of data while applying a qualitative-interpretive analysis of latent meanings (Mayring and Fenzl 2019). Following this procedure, we deductively built the starting categories according to our research interest and subsequently derived specific subcodes inductively from the material. We carried out the coding process in several rounds using three coders, implementing a qualitative validation process through repeated discussion and adaptation.

The data presented in this article is part of the larger research project “Religion as a Resource in European and International Climate Politics” at the Cluster of Excellence for Religion and Politics at the University of Münster. In subsequent phases of the project, we will compare the results discussed here with insights we gain through interviews with representatives from faith-based and non-religious organizations and data in the online texts of the organizations registered on the EU transparency register.

4 The presence of FBAs in EU climate governance

In 2020, 12,000 organizations were listed on the EU’s transparency register. Among them, there are 62 FBAs that name climate action as a field of interest. Among all the organizations listed in this field, 1.21% are FBAs. Of course, the register is not necessarily a complete listing of all the actors present in EU governance, as actors are only required to register to participate in certain forms of political engagement. Yet, it is unlikely that reality differs vastly from this picture. Thus, while FBAs are active in this political field in the EU, they play only a minor role, numerically speaking (Fig. 1).

However, these FBAs come from a range of religious backgrounds, with a strong emphasis on the Christian faith (77%). Given that, according to data from the Eurobarometer 2019 on Discrimination in the European Union, about 97% of the EU’s population who affiliated themselves with a religion claim to be Christian this predominance is not surprising.Footnote 3 Among the Christian denominations, Catholic FBAs, in particular, are present in this thematic field at the EU level (about 46% of the Christian FBAs belong to this denomination), followed by Protestant Christians, who amount to approximately 23%. In addition, Orthodox, Anglican, and Mormon organizations seem to be active Christian FBAs in EU climate politics. It is striking that about 21% of the Christian FBAs in the field of EU climate politics identify as ecumenical and thus do not represent a single denomination or do not (openly) affiliate with one specific Christian denomination. This could be the first evidence of inter-Christian cooperation on the topic of climate action (Fig. 2).

In addition to Christian FBAs, there are many different religious backgrounds among the FBAs working on climate action represented in the EU’s transparency register. At 6%, the ratio of Muslim FBAs in this data is even higher than the percentage of Muslims in the EU’s population who affiliated themselves with a religion (2% according to the Special Eurobarometer 2019 on Discrimination in the European Union). The higher percentage of Muslim FBAs may reflect the absence of an overarching Islamic organization that centralizes and coordinates the interests and concerns of Muslims within the EU. Similarly, new religious and spiritual movements, which are mainly close to the Hindu tradition, and Pagan FBAs constitute a greater portion of the registry than in the EU’s population. This may reflect a particular proximity to nature. However, this may also be the result of their overall small number.

5 FBAs’ normative positioning in the dialogue

During the Article 17 dialogue “The European Green Deal. Preserving our Common Home”, the participating FBAs notably emphasized two norm clusters that have the value of responsibility for creation at their core. Indeed, the degree to which FBAs present a homogenous picture in this regard is striking. On the one hand, they accentuate a responsibility towards nature. On the other hand, they stress a responsibility towards other humans and aspects of justice that are connected to this. Hence, the similarities in their points of view, religious-based values and duties could easily facilitate synergetic climate norms.

5.1 Responsibility towards nature

The statements made by the FBAs problematize climate change and point out its human-induced character. From their perspective, the existing economic and societal system enables over-consumption, materialism, and emissions and leads to the destruction of nature. Some of the statements further divide the problem into two: a systematic aspect and an individual aspect. They consider the economic system to be responsible for climate effects but also highlight problems arising from personal attitudes and behaviour:

There is a lot of talk of decarbonization and the poison which carbon represents vis à vis the atmosphere, but we don’t say what the Buddha said was a big problem of humankind 2600 years ago: Greed. Avidity. And that’s why we got to solve the problems of greed and cupidity. (Representative of the French Buddhist Union)Footnote 4

In order to end mankind’s destruction of nature, the FBAs unanimously promote change on both levels. On the systemic level, they call for political action to affect a paradigm shift and, on the individual level they demand a change of attitudes. They connect the latter to a conversion to a faithful way of living and acting according to one’s knowledge. According to their arguments, just talking about a climate emergency would not be enough. Rather, religiously inspired change in our way of life is what matters: “Calling ourselves Muslim is not enough. It says in the Koran several times, it’s about believing AND doing good deeds” (Representative of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science).

At the same time, all FBAs who participated in the dialogue advocated for taking immediate practical action and leading by example. Furthermore, the Muslim and Christian representatives harmoniously stress the importance of hope as a specific faith-based resource. They argue that, their faith inspires them to act in the right way, even if situations seem hopeless.

The statements by FBAs connect both problems and required actions to underlying values. In the FBAs’ views, deep-rooted values, faith, and religious traditions can motivate the radical change required to successfully tackle climate change. They promote the protection of nature as God’s creation and highlight God’s command that humans should care for his creation. Nature is presented as an expression of God’s work that has an intrinsic value. Consequently, living a faithful life should also involve loving God’s creation and therefore respecting planetary boundaries. The representative of the Vatican, as well as the Buddhist FBAs in particular, strongly emphasize the need to have compassion for nature:

You cannot care or protect […] what you don’t love. […] If we want to care for our common home, we need to start loving it. And loving is to discover how it works, the marvelous nature, I think as religions, we need to connect people with God as creator or God’s creation and in the contemplation of nature. All our religions are based on nature. And we have disconnected a little bit. We are responsible for that, but we have to start promoting it. Because if we love nature, it is impossible not to care about it. (Representative of the Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development)

However, the FBAs do not only mention positive emotions like hope, love, and compassion as specific faith-based resources in this context. Some of them also refer to negative emotions such as guilt and fear, if less frequently. The Muslim and Orthodox representatives stress that people will be judged depending on their deeds at the end of life, thereby reminding everyone of the need to live according to the requirements of faith.

5.2 Responsibility towards other humans

The second norm cluster brought forward by the FBAs during the dialogue focuses on responsibility towards humans. Here the statements highlight aspects of procedural, intergenerational, and global justice. The faith-based representatives underline that social factors must be at the centre of each political decision. Policies should rely on the values of responsibility and justice towards other humans, solidarity, and the participation of affected people. Statements by both Christian and Muslim representatives show that aspects discussed in the previous section on responsibility towards nature, such as the divine command to do good deeds and the warning of a judgment at the end of life, apply similarly here. These values add social weight to the problems the FBAs identify in relation to climate change and the social impact it imposes on humans. The Jewish representative even actively differentiated between divine and human-induced actions, stating that the problem of climate change is a consequence of the latter.

The FBAs promote comprehensive action that considers social aspects, or even prioritizes them, when tackling these problems. Concerning procedural justice, the FBAs draw attention to the social effects of climate-friendly adaptation measures (e.g., unemployment of coal miners). To face this challenge, they promote facilitating the participation of those affected in political deliberations. In their view, politicians should enable dialogues with diverse societal groups and listen to their concerns. Moreover, the faith-based representatives stress the importance of bringing people on board with climate adaptation measures.

Access, participation is all what it is about. Without having access to and participation of people, there is no way that we can address the targets of the sustainable development goals. (Representative of the Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development)

Policies and laws, even if important, they are not enough. They need to be properly explained and people need to be brought on board. People need to understand that caring for the environment is not against them, but for them. (Representative of the Conference of European Churches)

As another aspect of responsibility towards humans, the FBAs focus on global justice. In their view, climate change cannot be regarded solely on a European level. Instead, its effects must be considered on a global scale. Accordingly, actions for tackling climate effects must integrate the global perspective by, for example, providing more affected countries with funds.

Finally, the faith-based representatives also talk about intergenerational justice. They call on politicians to take immediate measures because the (lack of) action today will have irreversible effects for future generations. Future generations should not have to live with the environmental damage we cause today through our way of life. Thus, the FBAs declare climate change an emergency and highlight the task of integrating the losses of future generations into political considerations. The Islamic representative again connects this aspect with a moral appeal:

Maybe you should reconsider your path and behave a bit better so that indeed the aims of Sharia’h can be achieved, also for future generations. (Representative of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science)

5.3 Potential for agreement

The exchange of opinions between the members of the panel demonstrates their effort to emphasize the unifying aspects of their different points of view. Hence, they construct and shape the dynamics between norms by adding religious meaning based on a shared understanding of the problems and desired action. The dialogue’s title, “Preserving our Common Home” already indicates a focus on joint interests. It also links back to the title of the papal encyclical “Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home.” Perhaps not surprisingly then, the metaphor of the “common home” evolved as a central theme within the various statements: the political, humanist, scientific, and religious representatives emphasized that in the light of climate change, there is a common challenge to face, a common goal to achieve, and related courses of action to take.

The noted commonalities notwithstanding, the speakers’ contributions also illustrate that there is an awareness of differences in their approaches. In part, they have different backgrounds and offer different responses. This applies to the representative of the European Humanists Federation and the liberal Renew Europe Group in particular, as they expressed the greatest ideological distance from any religion during the dialogue. However, these differences did not seem to hinder agreement, rather they were perceived as a natural and legitimate circumstance in a pluralistic society. In particular, the representative of the liberal Renew Europe Group seems to allocate religion a role as a mediator able to reach conservative people and motivate them to act in an ecologically friendly way.

In this vein, different actors highlight the potential contribution of various sources addressing specific aspects of climate politics. For religion, as one of these sources, the participants see a particular potential to articulate moral elements and appeal to intrinsic motives. The FBAs themselves refer to their collective potential to motivate people to change their way of life and act, even in hopeless situations, to do something good. From their point of view, religions can give hope and appeal to deep values. Thus, FBAs advocate cooperation and mutual learning between religions and between religions and other actors to realize this potential on a broader scale. Likewise, non-FBA participants recognize the potential of specific religious contributions to the environmental discourse in their contributions to the dialogue. They agree that a different way of life will be necessary to fight climate change and that this goal will only be achieved if people are inherently convinced. They ascribe this task of convincing and motivating individuals, in part, to religious organizations. The speakers emphasize the religious potential to address climate-related problems through “deep values,” which means that they can give commonly shared ecological values a deeper meaning through their specific worldview (e.g., references to God’s creation). This seems to apply to questions concerning the relationship between humans and nature in particular, as well as to associated questions of justice:

Your work and advocacy have allowed the promotion of a comprehensive, holistic approach to ecology. You have in the past and you will be continuing in the future to ensure that the spiritual, ethical, the social dimension of ecology are better understood and taken into account when talking about the environment. […] Your voice is a particular voice, and it needs to be heard by politicians and by society at large. (Vice-President of the European Commission in charge of the Art. 17 dialogues)

In some cases, the speakers even report on occasions when they have already experienced this potential:

I know from experience that faith groups and leaders […] played a big role and have a big role to play. I can testify leading the negotiations for Paris how much the Pope’s publication Laudato Si’ has played a role. It has resonated with many. Even beyond, much beyond the catholic sphere. And on a day-to-day basis, as communities transition away from fossil fuels, my organization is very invested in Poland as well, we have seen the church playing a really big role in countering the narrative that seeks to undermine the idea of alternative pathways towards cleaner and decarbonized societies. I will always remember before the COP in Katowice, how the Church in Poland have published a prayer that was really putting climate change and action at the centre of their activities. It has created a total difference around the COP 24 in Katowice. (Representative of the European Climate Foundation)

Also, some politicians experience religion as a source of inspiration or motivation in climate politics themselves. For example, a Representative of the Renew Europe Group indicates this when reporting that a member of the European People’s Party (EEP) had identified the Pope’s appeal as a reason for her vote on climate change. The same EPP member also referred to the emotions of love for nature and guilt for acting in a non-sustainable manner—which the FBAs had raised earlier in the dialogue—as a motivating force. Another indication is given by another member of the European Parliament from the EPP parliamentary group, who indicates that he was “[p]ersonally […] very much inspired by the encyclical Laudato Si’ from Pope Francis” (Representative of the Committee on Environment, Public, Health & Food Safety, European Parliament). While other participants underline the potential of religion to motivate and reach others in climate politics, these two members of the European Parliament show that religious values may also reach the political process via channels other than FBAs.

5.4 What could hinder agreement? Scepticism and conflicting values

All in all, the statements made by the main speakers during the dialogue have a very diplomatic tone. They stress commonalities and the specific role of religion in climate discourse, which they see, primarily, as the provision of “deep values.” Nonetheless, there are also moments in the dialogue where participants, from the audience especially, raise issues that could hinder agreement. This demonstrates that conditions for facilitating understanding may differ across religions. In particular, there is some concern regarding a lack of familiarity with non-Christian faiths. The Muslim representative’s statement emphasized that this results in a higher pressure to justify Muslim approaches in public:

[F]or some reasons Islam seems to be getting less positive reviews in the news than some other faiths. I am not encouraging, or I am not expecting you to convert, but let’s show some curiosity in each other’s faith-centred approaches, opportunities for intrinsic motivation to work together on the current climate emergency. […] Let’s go for a joint Jihad. Yes, I am using that word purposely because it actually means: striving for good. And by using that word also reclaiming the hijacking of that word of this term by extremists and Islamophobes. (Representative of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science)

The subsequent reaction from the political actor who chaired the discussion acknowledges a lack of knowledge of prevalent Islamic concepts:

That was quite interesting, especially for me to listen to a very positive interpretation of Sharia’h and Jihad. We know that it was abused, but I was not aware that we can use it in such a positive way. (Representative of the Committee on Environment, Public, Health & Food Safety, EP)

In addition, speakers from the audience openly address conflicts between FBAs and other actors that could hinder agreement on climate change. Whereas the main speakers at the meeting emphasized commonalities, questions from the audience problematized religious “conservatism”. For example, one speaker from the audience drew attention to conservative religious values concerning family planning and conception. He argued that—in the context of an exploding world population—these traditional values may hinder progress in climate protection. Another audience member highlighted a contradiction between the FBAs’ statements and what he believed he knew about God’s commands to humans in Genesis:

Can I suggest that there is a contradiction here somewhere. In the Bible, without claiming to be steeped in these things, without being an expert, but in Genesis, it refers somewhere, I don’t have it off the top of my head, but it’s about fish, birds and all the creatures that live and crawl and die, it talks about them/it’s really a command to human beings to exercise dominion over creation. And I think that is contradictory to the injunctions we have been hearing around the room this afternoon. (Person from the audience)

The Catholic representative acknowledged that he is aware of this and that, in his view, this significant misunderstanding of Genesis has been used to legitimate an anthropocentric worldview. He argues, however, that this interpretation is not valid as, in a Christian understanding, it is not humankind but God who is at the centre of everything (Representative of the Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development). Furthermore, the Muslim representative argued that there is an equivalence of every species in the Koran. Therefore, from the Muslim perspective, humans may not abuse nature because it is a manifestation of God’s divine actions. They should learn from the creation about God’s will and his work, just as they learn from the verses of the Koran (Representative of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science). However, the Jewish representative argued that there is still a hierarchy of humans over nature, although this does not mean that humans have the right to abuse nature (Representative of the Central Israelite Consistory of Belgium).

Both examples, by demonstrating a lack of knowledge about Islamic concepts as well as scepticism towards Christian and/or Jewish values and conservatism, reveal the potential for open and hidden conflicting norm dynamics. In both cases, non-FBAs perceive religious values and concepts as part of a problem (whether the climate crisis or religion in politics in general), while the FBAs underline their role as a part of the solution. By explaining their religious values, some FBAs try to bridge those perceived divergences in the content of the norms.

6 Discussion and conclusion

This article aimed to identify the presence in and normative contribution of FBAs to the EU’s climate policy discourse. Regarding the latter, we were particularly interested in the potential for normative agreement and conflict among FBAs and between FBAs and other actors. We wanted to understand to what extent religious norms and ideas may function as a mobilizing resource in EU climate governance. In pursuit of our objectives, we first assessed the presence of FBAs via the European transparency register. We then evaluated the normative contribution of FBAs via a qualitative content analysis of a 2020 high-level dialogue on “The European Green Deal: Preserving Our Common Home” involving representatives of FBAs, non-FBA organizations, and EU institutions.

We focused on one specific dialogue. Further (comparative) research clearly is necessary. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that religion, or more precisely religious actors and religious norms, may provide a specific contribution to the European climate discourse by adding deep-rooted values that can give additional weight to problems of climate change and motivate action. The results thereby reveal a solid correspondence to similar findings relating to the UN (Glaab et al. 2019) while adding essential insight to that literature. In the dialogue analysed here, FBAs emphasize the association of climate values with creation thereby giving special meaning to nature and fellow humans and one’s responsibility toward them. Religiously framed emotions of love and compassion for nature, as well as suffering and guilt, emphasize this potential. In this context, FBAs highlight both individual and systemic problems leading to over-consumption and the destruction of nature. Accordingly, they demand fundamental changes to our values and justify them through the divine command to protect nature and vulnerable people while simultaneously cautioning against being held responsible for one’s actions at the end of life.

Agreement and a sense of the collective potential for religion to positively contribute to climate governance are also apparent in the views of representatives of different religious actors as well as between religious and non-religious actors. In particular, a consensus about the problems that must be faced regarding climate change appears to build a fundamental basis for such agreement. Discursive acts in support of such normative agreement include emphasizing and constructing commonalities and complementarity, i.e., the ability of religious organizations to mobilize additional resources. Thus, at some points, we witness the translation of religious norms and ideas into broader idioms, allowing them to be interpretable from different points of view. Representatives simultaneously highlighted the value of complementary approaches, with other actors and norms being considered more effective at reaching different segments of society. Hence, we see how actors actively shape the dynamics between norms and formed synergetic norms. On the one hand, the closeness of the FBAs positions and climate-related values towards the obligation to care for God’s creation makes it easy for them to find common grounds. On the other hand, actors with broader ideological distance attempt to shape climate norms by underlining the benefit of adding deep-rooted values (e.g., religious values) to the shared climate norms.

While most contributions to the dialogue focused on the normative common ground between FBAs or between religious and secular thought, a potential for normative conflict also became visible. Interpretations of religious thought as entailing a divine command for human dominion over nature, conservative religious stances on family planning and birth control, and references to a lack of knowledge and understanding, especially with respect to non-Christian faiths, reveal such potential sources of disagreement. They also highlight the extent to which religion may still function or be perceived as a barrier to tackling climate change. This is more so the case, given that our material led to a bias towards “climate-friendly” FBAs, willing to participate in the specific dialogue. Thus, future research will have to assess the likelihood of inner-religious conflict and conflict between religious and secular perspectives more broadly. Of course, conflicting normative views are not necessarily irreconcilable. Instead, such conflict is also subject to discursive (de)construction. Thus, future inquiries will need to focus specifically on the construction of (dis)agreement as well.

When looking at the potential for normative agreement and conflict, it is also interesting to note that the EU’s dialogue with religious actors is separate from other EU high-level climate dialogues with other stakeholders. FBAs are rarely invited to or participate in these other events (except implicitly as members of a more extensive societal network). Thus, access to FBAs in the EU is simultaneously institutionalized and institutionally limited, something that needs to be kept in mind when interpreting their potential influence. Given our findings on the specific contribution religious norms and ideas can make to climate governance, this could be an indication of untapped potential for mobilizing societal support for climate policies in general and the Green Deal in particular.

Notes

Societal actors can enroll themselves in the register if they intend to interact with EU institutions and decision-makers. The record aims to enable transparency in the lobbying process of the EU’s institutions. Registration is a precondition for some activities. For example, members of the European Parliament are only allowed to meet with lobbyists registered on the transparency register. https://ec.europa.eu/info/about-european-commission/service-standards-and-principles/transparency/transparency-register.

https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/webstreaming?d=20200128&lv=OTHER_EVENTS.

Please note that the transcript partly consists of text from simultaneous translation.

Participants were asked: “Do you consider yourself to be …?”. Possible Answers were: Catholic, Orthodox Christian, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim-Shia, Muslim-Sunni, Other Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, Non believer/Agnostic, Other, Refusal. 66% affiliated themselves to a religion. 64% affiliated to Christianity (European Commission 2019).

The quotes in this section all drawn from the transcript of the recorded Article 17 Dialogue “The Green Deal: Preserving our common Home”, which can be rewatched here: https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/webstreaming?d=20200128&lv=OTHER_EVENTS.

Literatur

Abdellah, Antar. 2020. The islamic declaration on global climate change. Middle Eastern Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences 1(2):77–93.

Baumgart-Ochse, Claudia, and Klaus Dieter Wolf (eds.). 2019. Religious NGOs at the United Nations. London: Routledge.

Beinlich, Ann-Kristin. 2019. And you, be ye fruitful, and multiply. In Religious NGOs at the United Nations, ed. Claudia Baumgart-Ochse, Klaus Dieter Wolf, 64–83. London: Routledge.

Bercovitch, Jacob, and Ayse Kadayifci-Orellana. 2009. Religion and mediation. International Negotiation 14(1):175–204.

Berger, Julia. 2003. Religious non-governmental organizations. International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 14(1):15–39.

Berger, Peter. 1999. The Desecularization of the world. In The desecularization of the world, ed. Peter Berger, 1–18. Washington: Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Björkdahl, Annika. 2002. Norms in international relations. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 15(1):9–23.

Carpenter, R. Charli. 2007. Setting the advocacy agenda. International Studies Quarterly 51(1):99–120.

Carr, Wylie Allen, Michael Patterson, Laurie Yung, and Daniel Spencer. 2012. The faithful skeptics. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 6(3):276–299.

Carrette, Jeremy R., and Hugh Miall (eds.). 2017. Religion, NGOs and the United Nations. London: Bloomsbury.

Casanova, José. 2019. Global religious and secular dynamics. Washington: Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs.

Clarke, Gerard. 2019. Faith-based organizations and international development in a post-liberal world. In Religious NGOs at the United Nations, ed. Claudia Baumgart-Ochse, Klaus Dieter Wolf, 84–105. London: Routledge.

Coni-Zimmermann, Melanie, and Olga Perov. 2019. Religious NGOs and the quest for a binding treaty on business and human rights. In Religious NGOs at the United Nations, ed. Claudia Baumgart-Ochse, Klaus Dieter Wolf, 106–125. London: Routledge.

Democratic Progress Institute. 2012. Civil society mediation in conflict resolution. London: Democratic Progress Institute. Working Paper.

European Commission. 2019. Special Eurobarometer 493. Discrimination in the European Union. Brussels: European Commission. https://doi.org/10.2838/5155.

Fehl, Caroline, and Elvira Rosert. 2020. It’s complicated. PRIF working paper, Vol. 49. Frankfurt: Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung.

Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization 52(4):887–917.

Glaab, Katharina. 2014. Religiöse Akteure in der globalen Umweltpolitik. In Religionen—Global Player in der internationalen Politik?, ed. Ines-Jacqueline Werkner, Oliver Hidalgo, 235–251. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Glaab, Katharina. 2017. A climate for justice? Globalizations 14(7):1110–1124.

Glaab, Katharina, and Doris Fuchs. 2018. Green Faith? Environmental Values 27(3):289–312.

Glaab, Katharina, Doris Fuchs, and Johannes Friederich. 2019. Religious NGOs at the UNFCCC. In Religious NGOs at the United Nations, ed. Claudia Baumgart-Ochse, Klaus Dieter Wolf, 47–63. London: Routledge.

Graf Antonia. 2016. Diskursive Macht. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Habermas, Jürgen. 2008. Notes on post-secular society. New Perspectives Quarterly 25(4):17–29.

Habermas, Jürgen. 2011. Vorpolitische Grundlagen des demokratischen Rechtsstaates? In Dialektik der Säkularisierung, ed. Jürgen Habermas, Joseph Ratzinger, 15–37. Freiburg: Herder.

Haynes, Jeffrey. 2013. Faith-based organisations at the United Nations. EUI Working Paper, Vol. 2013/70

Haynes, Jeffrey. 2014. Faith-based organizations at the United Nations. New York: Palgrave.

Hitlin, Steven, and Jane Allyn Piliavin. 2004. Values: reviving a dormant concept. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 30(1):359–393.

Huntington, Samuel. 1996. The clash of civilizations. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kommission Weltkirche der Deutschen Bischofskonferenz (ed.). 2021. Wie sozial-ökologische Transformation gelingen kann. https://www.digi-log.org/de/projekt/2/sws-studie. Accessed 25 July 2021.

Lehmann, Hartmut. 2007. Säkularisierung. Der europäische Sonderweg in Sachen Religion. Göttingen: Wallstein.

Leustean, Lucian. 2013. Religious actors in the European Union. Cuadernos Europeos De Deusto 48:95–106.

Liedhegener, Antonius. 2013. Mehr als Binnenmarkt und Laizismus? In Europäische Religionspolitik, ed. Ines-Jacqueline Werkner, Antonius Liedhegener, 223–238. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Mayring, Phillip. 2014. Qualitative content analysis. Klagenfurt: Beltz.

Mayring, Philipp, and Thomas Fenzl. 2019. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, ed. Nina Baur, Jörg Blasius, 633–648. Wiesbaden: Springer.

McCammack, Brian. 2007. Hot damned America. American Quarterly 59(3):645–668.

Morrison, Mark, Roderick Duncan, and Kevin Parton. 2015. Religion does matter for climate change attitudes and behavior. PLoS one https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134868.

Posas, P.J. 2007. Roles of religion and ethics in addressing climate change. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics https://doi.org/10.3354/esep00080.

Reuber, Paul, and Doris Fuchs. 2019. Politische Raumkonstruktionen von Gesellschaft und Umwelt in der päpstlichen Enzyklika “Laudato Si”. In Enzyklika Laudatio si’ – ein interdisziplinärer Nachhaltigkeitsansatz?, ed. Marianne Heimbach-Steins, Sabine Schlacke, 55–76. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Sachdeva, Sonya. 2016. Religious identity, beliefs, and views about climate change. In Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science, ed. Sonya Sachdeva. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

v. Sass, Hartmut. 2019. Von Deutungsmächten wunderbar verborgen. In Säkularisierung und Religion, ed. Irene Dingel, Christiane Tietz, 11–37. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Tucker, Mary Evelyn, and John Grim. 2001. Introduction: the emerging alliance of world religions and ecology. Daedalus 130(4):1–22.

White, Lynn, Jr.. 1967. The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science 155(3767):1203–1207.

Wiener, Antje. 2007. Dual quality of norms and governance beyond the state. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 10(1):47–69.

Wiener, Antje. 2008. The invisible constitution of politics. Cambridge: CUP.

Willems, Ulrich. 2007. Kirchen. In Interessenverbände in Deutschland, ed. Thomas von Winter, Ulrich Willems, 316–340. Wiesbaden: VS.

Wilson, Erin, and Manfred Steger. 2013. Religious globalisms in the post-secular age. Globalizations 10(3):481–495.

Winston, Carla. 2018. Norm structure, diffusion, and evolution. European Journal of International Relations 24(3):638–661.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klinkenborg, H., Fuchs, D. Religion: A resource in european climate politics? An examination of faith-based contributions to the climate policy discourse in the EU. Z Religion Ges Polit 6, 83–101 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41682-021-00082-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41682-021-00082-0