Abstract

This study analyzes the literature syllabi of Cambridge Assessment International Education (CAIE), a highly influential international education organization that determines curricula and conducts examinations for nearly one million students annually. Although CAIE describes its syllabi as internationalized and free from cultural bias and discrimination, little research has been conducted to confirm or reject these claims. Using a framework of postcolonial feminism and postdevelopment theory, this study analyzes author representation in CAIE literature syllabi to reveal potential colonial and patriarchal dimensions. We analyze the six CAIE literature syllabi in terms of author nationality, world region, and gender. The results indicate a clear bias in favor of European male authors and a consistent underrepresentation of women authors from the Global South. Authors of the MENA region are entirely excluded from the syllabi. Women authors from Latin America are also almost entirely absent. The study concludes that CAIE literature syllabi are not sufficiently international or multicultural, but instead reflects the continued legacy of colonial relations between British education and the Global South. Since the colonial era, CAIE has continued to enact banking education at a global scale by conceiving of the Global South as lacking in literature worthy of study. In order to begin to decolonize their literature syllabi, we suggest that CAIE should draw from diverse literature throughout World Englishes, especially literature written by women authors in the Global South.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cambridge Assessment International Education (CAIE), formed in 1858 in Cambridge, England, is an international not-for-profit organization that annually prescribes the curricula for nearly one million primary and secondary students. The organization is the largest provider of international education programs for students of 5 to 19 years of age (CAIE 2018b). According to CAIE (2018a), schools accredited by CAIE are located in over 160 different countries across 9 global regions, including North America, Latin America, the UK, and Ireland, Europe, Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Northeast Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia and the Pacific. The majority of these schools are private and located in the Global South (CAIE 2018a). The presence of CAIE fits within a larger contemporary context of growing international education, in which CAIE is one of the most influential organizations.

To understand the global influence of CAIE today, it is necessary to address the organization’s colonial history. CAIE expanded its global presence in the late twentieth century as a push to “civilize” colonized populations through an English-medium education. Now, according to its mission statement, CAIE seeks to:

provide educational benefit through provision of international programmes and qualifications for school education and to be the world leader in this field. Together with schools, we develop Cambridge learners who are confident, responsible, reflective, innovative, and engaged—equipped for success in the modern world. (CAIE 2018b)

A culturally neutral approach is cornerstone to CAIE, who say in developing their syllabi, they have:

This claim to “avoid bias of any kind,” including “indirect discrimination,” is investigated in this article, particularly in relation to secondary-level literature in CAIE. The combination of a growing international education system, the predominance of CAIE within the growing system, and the organization’s colonial history suggests that a critical analysis of CAIE syllabi may have significant implications for international education. If CAIE aims to be a world leader for education, the organization’s actions and inactions should be scrutinized and held to the highest standard.

Most studies that examine specific literature curricula in terms of race, gender, and cultural representation use participant interviews as their primary methodology. A number of studies found that curricula that include literature written by people of color, women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) authors enables a diversity of students to identify with characters and issues explored in the texts (Athanases 1998; Beach 2005; Glazier and Seo 2005). Athanases (1998) concludes that literature curricula that privileges white, straight European males marginalize students who are not within that narrow identity category. Another found that marginalized students experience empowerment by engaging with the counter-narratives in literary texts written by people of color and women (Beach 2005). In Singapore, a study found that the focus of literature curricula on Western authors contributed to students’ perceptions of literature as an academic subject with limited applicability to the local cultural context (Dass et al. 2012). All of these studies use interviews with students to analyze individual experiences with literature curricula implementation as they relate to race, gender, and culture.

Although student interviews are the most common methodology of analyzing the race, gender, and cultural representation within literature curricula, other approaches have been taken. Boston and Baxley (2007) use intensive textual analysis to demonstrate that the pedagogical use of literature written by black women is more relevant and empowering to black female students. Applebee (1991, 1992) conducted two studies with a more extensive scope that categorized texts used in US literature curricula in terms of literary genre as well as the race and gender of authors. Both studies concluded that the preponderance of white male authors in literature curricula marginalizes women and people of color in the classroom and in the canon. Like Applebee’s studies, our research categorizes texts by author identity to trace cultural and gender representation in broadly implemented literature curricula. However, while Applebee analyzed exclusion in literature curricula of the USA, our research concerns curricula implemented in over 150 countries, most of which are in the Global South. Therefore, this study offers critical insight into the colonial dimensions of the CAIE literature curricula that shape the education of students throughout the world.

Theoretical framework

Postcolonial theory

Our study addresses the colonial history of CAIE with postcolonial theory, which argues that since colonialism involves the profound transformation of societies and culture, scholars should study and resist the lasting impacts of colonialism into the present era (Bhabha 2012; Fanon 2007; Said 1994). Postcolonial theory is especially concerned with the continued unequal power relations between societies that were colonized and their former colonial metropoles. To contextualize the geography and gender of the CAIE literature curricula, it is necessary to trace the organization’s colonial roots.

CAIE is the most widely recognized English-medium qualification provider in many countries that were colonized by Britain, such as India and South Africa. The CAIE curricula are developed by the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UCLES), also known as Cambridge Assessment. UCLES began administering school examinations in Britain’s colonial territories in 1864. Thereafter, it was instrumental in Britain’s systematic re-education of its colonial subjects to establish British hegemony in the realm of knowledge production (Ball 1983; Bray 1997, 1998; Lillis 1985; Omolewa 1976). The global expansion of UCLES in the late nineteenth century was part of a broader push among British institutions to “civilize” colonized populations through British-led English-language education. British international education has been often criticized as a colonial instrument that marginalizes local perspectives and, more recently, as a neocolonial project (Altbach 1975; Bray 1993, 1997; Quist 2001).

Freire (2012) focuses on the way in which the colonized internalize the oppressive discourses of the colonizer. He identifies the colonial educational model as a key site in which oppressed students develop a sense of racial inferiority. By positing the male colonizer as the teacher who “knows,” colonial education considers students to be devoid of useful perspectives, characterized by lack rather than fullness. At the intersections of marginalized identities, and in particular those of women from the Global South, education has the potential to profoundly disempower through internalized oppression.

Similarly, Freire (2012) problematizes the banking concept of education, which positions knowledge as static and originating primarily from the educator. This knowledge is then deposited into students’ minds without serious concern for their own subjectivities or agency. Banking education projects “an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as processes of inquiry” (Freire 2012, p.72). This was the logic of the colonial education system through which the colonizer intended to lift the colonized from their “savage ignorance” and introduced “civilized” ideas into their minds. The banking concept of education reflects the developmental dynamics between CAIE and schools in the Global South, because CAIE decides which texts are useful for students to read, regardless of the potential importance of community and locality. CAIE can be seen in this relationship as the knower, while schools in the Global South are being deposited certain information deemed important by CAIE. To help determine whether or not Freire’s postcolonial critique of banking education applies to CAIE literature syllabi used today, our data classifies authors by location within the North-South divide, under the assumption that this generally correlates to the geographies of the colonizer and colonized.

Postdevelopment theory

Postdevelopment theory argues that colonial narratives have been reworked into development discourses, and fulfill a similar, but not identical, function (Brigg 2002; Simon 2006). Just as colonial discourse and its banking education regard the colonized as devoid of knowledge and thus requiring the colonizer’s education, development discourse constructs the Global South as defined by a fundamental deficit or lack (Freire 2012). This lack extends into “a series of factors linked to cultural considerations, such as education and the need to foster modem cultural values” (Escobar 2012, p. 40). Postdevelopment theory is therefore helpful in considering CAIE’s intervention into educational spaces in the Global South.

Although Cambridge Assessment’s philosophies of curriculum development and international development are not public, some materials on their website indicate what they might be. Among those is a Cambridge Assessment promotional video on what Cambridge Assessment “means for developed and developing countries,” in which Professor James Tooley observes that:

the curriculum and the assessment system that is used in these countries [like West Africa is] the one that was brought in circa 1900… by the British, and it has not really changed over much. They have not been able to bring their curriculum and assessment system up to date for the modern interconnected world. (Tooley 2014)

The portrayal of the Global South as spatially disconnected from modernity and temporally located in the past stems from colonial discourses, and is still present in some theories of development today. According to Tooley (2014), “in terms of national curricula, and national examinations, I’m not convinced that governments are equipping people very well for the international world” (Tooley 2014). Instead, increased global trade and migration allows international organizations to educate students “almost irrespective, sometimes, of what the Department of Education is doing in the country.” Tooley sees Britain as a principal driver of education in many countries of the Global South, during colonialism and into the present era. This conception is disempowering for educators in the Global South and serves to reinforce dependency on the Global North. Given the colonial history of UCLES, CAIE’s continued influence in the Global South risks producing neocolonial discourses if Cambridge Assessment does not critically re-evaluate its past and present.

As a development education organization, CAIE may serve to disempower local schools, teachers, and students, conceiving of them as inherently underdeveloped and in need of help from foreign experts. The idea that marginalized students must be “developed” by actors from the Global North has received criticism from both postdevelopment theory and critical pedagogy, two fields of thought that merge in the educational theories of Paulo Freire (Pieterse 2000, p.177). Literature education is of particular concern here because of the history of colonial literature in articulating the differences between the civilized European and the backwards indigene, notably in Kipling’s (1899) “The White Man’s Burden” and Dickens’ (1853) “The Noble Savage.” The myth that the colonized is inferior in knowledge, and thus needs the goodwill of European culture and its educators, continues to the present day in development discourse. By tracing the geography of authors in the CAIE literature syllabi, it can be determined whether the literature of the Global South is deemed worthy for study, or whether particular cultural standpoints are being privileged over others.

Postcolonial feminism

Postcolonial feminism argues that women in Latin America, Africa, and Asia are marginalized in mainstream feminist discourse, which largely centers the experiences of white women, as well as within analyses of colonialism, which privilege the perspectives of the colonizer (Alexander and Mohanty 2012; Suleri 1992; Hooks 2004). Mohanty (1988) criticizes Western colonial discourses that group women from the Global South as a monolithic category and calls for an intersectional analysis in which race, class, and gender are seen as interconnected and inseparable structures of violence. Thus, our study resists the temptation to analyze the authors by single-identity categories like “gender” when possible. Instead, we separated authors into region-gender groups whenever possible, such as “women in Europe” or “men in Asia.” This allows our analysis to focus on the ways in which women authors from Latin America, Africa, and Asia are often simultaneously marginalized within multiple axes of identity.

Postcolonial feminism is a lens which has been underutilized in analyses of transnational education. A considerable body of research has used postcolonial theory to critique international education (Rizvi 2005; Tikly 2001; Woolman 2001). Far less research has considered the relationship between transnational education and gender (Kanan and Baker 2015). The mainstream approach to investigating development education and transnational education does not use the intersectional analysis proposed by postcolonial feminism, and thus cannot adequately explain the convergence of patriarchy and colonialism as they shape the contemporary educational landscape. One objective of this research is to investigate whether the politics of author representation in international literature education can be explained merely through a gender or postcolonial analysis, or whether it lies somewhere at the intersection of colonialism and patriarchy.

Our theoretical framework possibly strays from postcolonial feminism in our analysis of women in the Global South as a category of author. This risks reproducing what Mohanty (1988) calls “monolithic images of ‘Third World Women’ as women who can only be defined as material subjects, not through the relationship of their materiality to their representations” (p.352). She observes that such discourses intimate that all women of the Global South have similar experiences and perspectives, regardless of ethnicity and class. Despite these risks, we chose to analyze, in addition to groups based on region and gender, another grouping of four broad authorships: women in the Global South, men in the Global South, women in the Global North, and men in the Global North. This mode of analysis is merely supplemental to the predominant region-gender analysis, tracing the broader postcolonial implications of author representation in the literature syllabi.

Methodology

We chose to analyze the curricula of Cambridge International Examinations because of its prominence in transnational education and internationalized curricula. Cambridge Secondary 2 and Cambridge Advanced are the only Cambridge programs that prescribe set texts for literature, and are thus the focus of our study. Since this study was mainly concerned with the applicability of CAIE literature curricula in transnational contexts, we chose to omit syllabi that are only used in single countries, such as 0427 (US only) and 0477 (UK only).

Of the four qualifying programs—IGSCE, O Level, AS/A Level, and Pre-U—six syllabi were eligible for analysis. Our data set consisted of all literary works mentioned as set texts in these six syllabi, which totaled over 600 poems, dramas, short stories, and novels. Because many syllabi were published in different years and for different examination dates, we always chose the most recent syllabus. For example, the syllabus used for O Level (2010) is set for examination in 2019, while the syllabus used for Pre-U (9765) is set for 2018, but both syllabi are the most recent available for their respective programs.

Most syllabi consisted of two different kinds of text: set texts and portfolio texts. The former are texts that are required for study and are eventually used in the final assessments, while the latter are texts that are suggested for individual portfolio work. After narrowing in on the set texts of the six syllabi, we gathered data regarding the variables below.

Type of work

Texts were divided into four categories: poems, short stories, novels, and dramas. These categories roughly correlate with distinctions drawn in the Cambridge syllabi themselves. Novels and dramas are likely to occupy more time in the classroom per text, and thus we analyzed all four categories as separate data sets. Extensive poems, such as one of the Canterbury Tales, were considered to be poems despite their length. Small anthologies of short plays by one author were counted as single dramas. Dividing texts into types also allowed us to identify which areas of the syllabus were most problematic in terms of author representation.

Gender of author

To analyze the diversity of gender among set texts, the gender identity of each author was collected. Despite the significance of gender identity as a standalone variable, we were most interested in studying the intersectionality of gender with the variables of nationality and position within the Global North-South divide (see below for the description of the latter two variables). This decision coincides with the call for intersectionality analysis within postcolonial feminism (Mohanty 1988). We were not aware of any authors in the CAIE syllabi who identify without gender, or with non-binary genders.

Nationality of author

To determine whether the set texts represent a truly international corpus, we measured variables of author identity such as global region and nationality. Nationality was defined as country of citizenship. Citizenship information was readily available because authors featured in CAIE syllabi are well-known public figures with prolific bodies of published work. In the case of multiple citizenships or changes of citizenship, we almost always considered the later citizenship to represent nationality, rather than citizenship of birth. This gave a result that accurately represented the body of national literature to which the author is considered to have contributed. The sole exception is Aravind Adiga, the Indian author who acquired Australian citizenship. Since he currently resides in India and has published a large portion of his bibliography while living in that country, we chose to consider him as from India, in contradiction to the method we developed (Hall and Wilson 2008). Authors who have lived overseas without changing their citizenship status are considered to be of their country of origin (e.g., Anita Desai is listed as of Indian nationality in our data despite having lived for a considerable amount of time in the USA).

Position of nationality within Global North-South Divide

We chose to classify authors by location within the North-South divide, under the assumption that this generally correlates to the geographies of the colonizer and colonized (Sparke 2007). We defined the Global North as consisting of countries that rated 0.8 and over in the 2013 Human Development Index, of the (United Nations Development Programme 2013). This includes the USA, Europe, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. The Global South includes Latin America (except French Guiana), the Caribbean, Africa, and most of Asia. On the syllabi we analyzed, there were no authors from countries that would put this definition of Global South and Global North at odds with commonly used classifications, such as Turkey, Russia, and Qatar.

Region

We assigned a region to each author based on nationality. The regions were Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Europe, Asia, Australasia, Latin America, and North America. We used the United Nations’ definition of Sub-Saharan Africa. We defined MENA with the broadest geography possible, including Turkey and other countries often not considered part of the region. Europe was considered to be the Western European and Others Group, with the exclusion of Canada, Israel, Turkey, Australia, and New Zealand. Asia was broadly defined as including Central Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. Australasia was Australia and New Zealand. North America consisted of the USA and Canada. Latin America was defined as Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. Exclusions of other regions of the world, such as Eastern Europe, reflect areas that are not represented in the CAIE syllabi that we analyzed.

Results

Type of work

We analyzed our data as four separate data sets, divided by type of work: Poetry, dramas, short stories, and novels. Poetry represented 80.7%, novels represented 5.3%, short stories represented 8.8%, and dramas represented 5.1%, of total texts.

Gender identity within four types of work

Our analysis begins with observing the gender identity of the authors within the four types of work. Table 1 shows that three of the four types of text have more male authors than women authors, with dramas accounting for the largest difference at 90.6% men and 9.4% women. The novel is the only category where women are favored, with women accounting for 60.6% of the works.

Gender identity and North/South divide

When expanding identity variables to include both gender identity and position in the North-South divide, the data demonstrates the intersectional nature of marginalization in the literature syllabi. It should be noted that men from the Global North are the most represented identity in three of the four types of work. In every category of text, men from the Global North have more works represented than men from the Global South and women from the Global South combined. While considerably more women novelists are represented than male novelists, women from the Global North outnumber women from the Global South by more than 5 times. Women from the Global South authored 1.2% of the poetry, 9.1% of novels, 14.5% of short stories, and none of the dramas. Author representation appears to operate intersectionally in the syllabi. However, position within the North-South divide was somewhat more determinant of underrepresentation than gender.

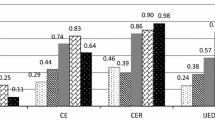

Gender identity and global region

A regional analysis of authors in the CAIE literature syllabi also demonstrated intersectional dynamics of author representation (Table 2). Europe and North America were overrepresented in every type of literature, with men usually taking precedence in their category. Latin American, African, and Asian authors were consistently underrepresented, regardless of the type of work. Women from these regions were almost always less represented than their male counterparts. There were no works at all by authors of the MENA region.

Europe had considerable influence in each work type, representing 67.2% of poetry, 71.9% of dramas, 40.0% of short stories, and 48.5% of novels. In each category, European authors were more represented than any other single region. European men were the single largest group represented in each category, except novels, in which they were equal with European women.

North America was the second most represented region in each category, with 16.3% of poetry, 18.8% of dramas, 23.6% of short stories, and 18.2% of novels. Types of work for North American authors were heavily gendered, with men dominating North American poems and dramas, and women dominating North American short stories and novels.

Authors from Asia had considerably less representation than their European and North American counterparts. There were no dramas written by an Asian author. Asia was hardly represented in poetry, with just 1.4% of the poems. Women in Asia were represented in just 3.0% of the novels, 0.8% of the poetry, and none of the dramas. However, women in Asia were represented in 10.9% of the short stories, which was the third most represented group after men in Europe (36.4%) and women in North America (16.4%).

African authors were best represented in novels, in which they consisted of 12.1% of texts. They also represented 10.9% of short stories and 9.4% of dramas. In poetry, African authors are almost entirely excluded, representing just 0.6% of all poems. Women authors from Africa have equal representation as male authors from Africa in short stories and novels, but are entirely excluded from poems and dramas.

There are no authors from Latin America represented in short stories, novels, or drama. Latin American authors make up 6.2% of the poetry in the syllabi. Of that 6.2%, male authors were represented in 93.5% of the works. The only literature by a Latin American woman is a single poem by Guyanese author Grace Nichols, which appears in two of the six syllabi.

The UK is the favored country of texts in every type of work, with at least double the representation of the second most favored country—the USA—in three of the four sections. When combining the selected works from the UK and the USA, the two countries’ presence accounts for over half of the texts in each of the four categories of text. Specifically, authors from both countries combined makeup 73.6% of all poetry, 60.7% of novels, 61.8% of stories, and 78.2% of all dramas.

Poetry by UK men makes up 29.2% of the category, while UK women make up 28%. Men from the USA account for 14.7% of poetry and US women account for 1.6%. With the exception of men from Australia and Ireland, women and men from the UK and the USA are the four most featured identities in the poetry section. In the novel section, work by women from the UK is slightly favored over UK men, but double that of women’s work from the US and eight times the work of US men. Men from the UK are heavily favored in the story section. Women from the USA account for the second largest amount of work in the entire section at 16.4%, more than that of all other single countries featured in the story section. UK men write 53.1% of all dramas, while men from the US account for the second largest amount of dramas (15.6%). Every other country featured in the poetry section accounts for at least half of the number of selected texts of the UK and the USA.

Work by syllabi

The data set in this study consists of six syllabi. All syllabi had somewhat similar proportions of author representation with the exception of Pre-U Literature in English and IGCSE World Literature, which had noteworthy differences.

Pre-U Literature in English had far less diversity of authorship than the rest of the syllabi. There were no authors of the Global South featured in any category of work. The dramatic works were written entirely by European authors, 71.4% of which were written by men. European authors wrote 87.5% of the novels and 58.2% of the poems featured.

Despite its ostensibly global scope, IGCE World Literature featured only marginally diverse authorships, and only pertaining to some types of work. There were two novels in the syllabus, one by Zimbabwean woman Tsitsi Dangarembga and the other by Australian woman Henry Handel Richardson. The poetry on the syllabus was 42.9% written by authors from the Global South, which is remarkable given that the average representation of poets from the Global South for all six syllabi was just 8.2%. That being said, women from the Global South wrote just 7.1% of the poems in the World Literature syllabus, demonstrating that intersectionality remains at work here. Short stories and dramas were less diverse in the World Literature syllabus than the average of all six syllabi, with the 90% of the novels in this syllabus written by authors from the Global North and the dramas written entirely by men from the Global North.

Discussion

Our results confirm that the literature syllabi administered by CAIE reinforce the cultural hegemony of literature from men in the Global North. Women in Sub-Saharan Africa, MENA, Asia, and Latin America are severely underrepresented in the CAIE literature syllabi. Their exclusion in relation to both men from the Global South and women from the Global North suggests that their literature is subject to intersectional oppression. It is therefore imperative that CAIE considers that its literature curricula may be influenced by patriarchy and a legacy of colonialism.

The CAIE literature syllabi enact banking education at a global scale by depositing literature from the Global North into the educational spaces of the Global South. This transnational banking education may engender internalized oppression among those in the Global South who encounter the curricula in the classroom (Lowery 2016). As students in the Global South learn to read and analyze literature in CAIE syllabi, they also learn that the literature from Southern authors is less worthy of attention than that of Northern authors. At the same time, as students from the Global North engage with these curricula, they reinforce that their own perspectives are the most important to global culture. Since marginalization in the CAIE literature syllabi operates at the intersection of colonialism and patriarchy, women in the Global South are faced with curricula that do not regard their perspective to be of equal value. While in Freire’s banking education teachers are posited as the sole possessor of knowledge, CAIE’s banking education at the global scale may render teachers as lacking literary knowledge and therefore requiring guidance. Just as students are mandated to read certain literary works deemed important by CAIE, teachers are mandated to teach these specific texts. This encroaches upon the professional autonomy of teachers to engage with works that they deem significant for their specific communities.

The CAIE literature syllabi reflect a presumed “lack” of English literature in the Global South that justifies its banking pedagogy and developmental relationship with Southern educational spaces. In addition to conceiving of students and teachers as empty of knowledge, the banking education present in CAIE’s literature syllabi empties a broader cultural terrain by refusing to acknowledge the Global South as an abundant source of English literature. This cultural terrain, which Kachru (1992) calls “World Englishes,” consists of a plurality of cultural spaces that are excluded from author representation in the CAIE literature syllabi. For instance, MENA has a significant population of English speakers, 28 million of whom are in Egypt alone (Euromonitor International 2012, p.128). The absence of authors in the CAIE syllabi who are from Egypt or other MENA countries omits a significant population of English speakers. Similarly, India and Philippines together have 169 million English speakers, over half the number of English speakers in Europe (Doughty 2010; Gonzalez 2004, p.10; Masani 2012). Despite the considerable prevalence of Asian countries in the English-speaking world relative to European countries, Asian authors are always far less represented in CAIE syllabi: Novels by European authors are represented five times more than those by Asian authors, poems by European authors represented 48 times more than those by Asian authors, and dramas include no Asian authors at all.

English-language literature is culturally significant to English speakers on every continent, as evidenced by various prizes awarded regularly for English literature from around the world. These include the Caine Prize for African Writing, the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, the Barry Ronge Fiction Prize (South Africa), the Singapore Literature Prize, the Palanca Awards (Philippines), the Gratiaen Prize (Sri Lanka), and the Guyana Prize for Literature. It is the responsibility of influential educational institutions like Cambridge Assessment to acknowledge World Englishes and their crucial yet historically marginalized contribution to literature and to present them as equally significant in classrooms across the world.

To begin decolonizing the banking education that operates through its literature syllabi, CAIE must fully recognize literature from the Global South—especially literature written by women authors in the Global South—as not only prolific but also essential to literature education. Literature syllabi that center perspectives of the Majority World are necessary for both cultural and personal empowerment. In presenting a postcolonial feminist approach to standpoint theory, Lenz (2004, p.100) argues that postcolonial literature written by women authors presents standpoints that engender “the deconstruction and decentralization of dominant ideologies.” Not only does deconstructing representations of gender, race, and other identity categories contribute to a socially liberatory education, it also marks a cultural space from which to resist internalized oppression.

CAIE should ensure that the corpus of literature represented in its syllabi reflects the international significance of Englishes as well as the institutional scope of CAIE’s globally-implemented curricula. In each syllabus, Cambridge Assessment (2014, p.60) includes the claim that it “has taken great care in the preparation of this syllabus and related assessment materials to avoid bias of any kind.” Our results show that CAIE literature syllabi feature a marked bias that favors male authors from the Global North. As the world’s largest international education provider, CAIE is tremendously influential in establishing norms and setting standards for international education. If its education intends to impart an international perspective upon students, then the global culture that CAIE reproduces and presents to students is one in which the perspectives of European men remain central. To work towards a form of international education that challenges colonialism and patriarchy, CAIE should proportionally include female and male authors from all regions of the world.

Limitations and considerations for future research

Our analysis is rooted in postcolonial feminism, which stresses the avoidance of grouping women from the Global South into one identity category. Instead, Mohanty (1988) argues that ethnicity and class must also be considered to gain a more nuanced understanding of the social positions of women. This type of analysis was not possible in our study. While our analysis avoided analyzing single identities, like “gender,” we were unable to address the identity politics of ethnicity and class, thus greatly limiting our intersectionality analysis. North-South position, as determined in our study by most recent citizenship obtained, can relate to both ethnicity and class but does not explicitly describe either. Defining authors in terms of social class would be very difficult at this scale of quantitative analysis. We considered sorting authors by ethnicity, but decided not to because that approach would not adequately address the contentious politics of defining race and ethnicity. This study’s lack of ethnicity and class analysis means that our results do not trace the mechanisms of exclusion that operate within numerous axes of identity simultaneously. The results only identify whether or not there is a problem of author representation in the CAIE curricula, rather than attempt to explain the nuances of identity politics and literature (re)production in the diverse political, cultural, and geographical contexts of the Global South.

Our analysis was also limited in its definition of nationality. Although nationality is commonly defined as country of citizenship, in terms of identity it embodies a shared history, language, and geography. By defining it in terms of citizenship in this study, complexity is sacrificed in favor of precision. Accordingly, this study does not account the multiple national identities that some authors may have.

In addition, our research was limited in our gender analysis. While there are no authors who publicly identify as nonbinary or agender in CAIE syllabi, our use of a binary definition of gender did not address the complexities of gender identity. Our analysis was not explicit in discussing the limitations of excluding transgender, nonbinary, and agender authors from CAIE syllabi. Similarly, this study did not examine the representation of LGBTQ authors in the CAIE syllabi, which is particularly relevant given the historical role of literature in mainstreaming LGBTQ perspectives.

The scope of our research left us unable to investigate how CAIE syllabi and texts are used in the classroom, the content in the selected texts, and how the texts affect student experiences. Further research into these areas could address larger questions about text usage in the classroom and the relationship between content and diversification. Such research would attend to the agency of students and teachers, examining the ways in which they respond to and challenge the literature syllabi’s centering of male authors from the Global North.

The selection process for literature in CAIE syllabi lacks transparency, making it difficult to pinpoint their motives and theoretical rationales. This barrier limited our ability to place our statistical findings within the context of CAIE selection philosophy, which would ultimately provide a richer critical analysis of CAIE’s syllabi selection process. While we reached out to the CAIE to inquire about their philosophy and the selection of their literature texts, we were not given the opportunity to have a discussion around this topic.

Conclusion

The results of our study indicate that the colonial legacy of CAIE continues to shape its literature curricula. Upon close examination of the selected texts in CAIE literature courses, it is apparent that the authors represented in the syllabi are overwhelmingly male and from the Global North. Women authors from Sub-Saharan Africa, MENA, Asia, and Latin America are severely underrepresented. Despite the cultural prevalence World Englishes and literature in these regions, CAIE mostly overlooks their value. This suggests that CAIE curricula are not substantially multicultural, but instead teach nearly one million students across the world that literature written by Southern women are less worthy of study. The results of this study demonstrate that in the CAIE literature syllabi, women from the Global South are being marginalized at the intersection of patriarchy and colonialism, and that the geographic and gender inequalities of its author representation can only be understood by considering both modes of exclusion.

If CAIE intends to provide an education that holds the perspectives from women in the Global South equal to those of men in the Global North, it must deeply reconsider the author representation in the selected texts of its literature syllabi. CAIE should be particularly careful to avoid reproducing banking education, since it unilaterally sets the curricula for students in dozens of countries across the Global South. Teachers and students in the Global South receive CAIE’s curricula from across the colonial difference, far removed from CAIE’s discussions and decision-making regarding the curricula in their classrooms. Therefore, the rationales and philosophies that inform CAIE syllabi should be made transparent so that they are open to analysis and critique from those affected by its decisions.

CAIE not only governs the education of students globally, it also substantially influences the agendas of international education as a whole. The colonial and patriarchal exclusions discussed in this study, through which cultural significance is located in literature produced by men in the Global North, raise concerns about the type of development that international education organizations are working towards. The construction of the Global South as an emptied cultural terrain not only undergirds the injustices of colonial education, but it also continues to enable the inherent inequalities of developmental relations between international organizations and the peripheral spaces upon which they intervene. CAIE’s literature syllabi appear to be reproducing internalized oppression in the very spaces where it should be empowering students with its education.

References

Alexander, M. J., & Mohanty, C. (Eds.). (2012). Feminist genealogies, colonial legacies, democratic futures. New York, NY: Routledge.

Altbach, P. (1975). Literary colonialism: Books in the Third World. Harvard Educational Review, 45(2), 226–236.

Applebee, A. N. (1991). A Study of High School Literature Anthologies. Report Series 1.5. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED333468.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2018.

Applebee, A. N. (1992). Stability and change in the high-school canon. The English Journal, 81(5), 27–32.

Athanases, S. Z. (1998). Diverse learners, diverse texts: Exploring identity and difference through literary encounters. Journal of Literacy Research, 30(2), 273–296.

Ball, S. J. (1983). Imperialism, social control and the colonial curriculum in Africa. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 15(3), 237–263.

Beach, R. W. (2005). Conducting research on teaching literature: the influence of texts, contexts, and teacher and on responses to multicultural literature. In Proceedings from The National Reading Conference. Oak Creek, WI: NRC.

Bhabha, H. K. (2012). The location of culture. Oxon: Routledge.

Boston, G. H., & Baxley, T. (2007). Living the literature: race, gender construction, and black female adolescents. Urban Education, 42(6), 560–581.

Bray, M. (1993). Education and the vestiges of colonialism: self-determination, neocolonialism and dependency in the South Pacific. Comparative Education, 29(3), 333–348.

Bray, M. (1997). Education and colonial transition: the Hong Kong experience in comparative perspective. Comparative Education, 33(2), 157–170.

Bray, M. (1998). National self-determination and international dependence: The organisation and control of secondary school examinations in the small states of the Commonwealth. Assessment in Education, 5(2), 151–173.

Brigg, M. (2002). Post-development, Foucault and the colonisation metaphor. Third World Quarterly, 23(3), 421–436.

Cambridge Assessment (2014). Syllabus: Language and Literature in English 8695 (4th version). http://www.cambridgeinternational.org/images/164512-2016-2018-syllabus.pdf . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Cambridge Assessment International Education (2018a). Find a Cambridge school. http://www.CAIE.org.uk/i-want-to/find-a-cambridge-school/ . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Cambridge Assessment International Education (2018b). What we do. http://www.CAIE.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/ . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Dass, R., Chapman, A., & O'Neill, M. (2012). Literature in English: how students in Singapore schools deal with the subject. Malaysian Journal of ELT Research, 8(2), 1.

Dickens, C. (1853). The noble savage. Household Words, 7(168), 337–339.

Doughty, S. (2010, October 4). English now the language of Europe as two-thirds of continent’s people can speak it. The Daily Mail. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1317470/English-language-Europe-thirds-continents-people-speak-it.html . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Escobar, A. (2012). Encountering development: the making and unmaking of the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Euromonitor International. (2012). The benefits of the English language for individuals and soCAIEties: quantitative indicators from Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/Euromonitor%20report%20final%20July%202012.pdf . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Fanon, F. (2007). The wretched of the earth. New York, NY: Grove.

Freire, P. (2012). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Glazier, J., & Seo, J. A. (2005). Multicultural literature and discussion as mirror and window? Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(8), 686–700.

Gonzalez, A. (2004). The social dimensions of Philippine English. World Englishes, 23(1), 7–16.

Hall, L., & Wilson, P. (2008). Booker for loner Aravind Adiga with liking for Aussie egalitarianism. Surry Hills: The Australian.

Hooks, b. (2004). Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kachru, B. (1992). World Englishes: approaches, issues and resources. Language Teaching, 25(1), 1–14.

Kanan, H. M., & Baker, A. M. (2015). Influence of international schools on the perception of local students’ individual and collective identities, career aspirations and choice of university. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(3), 251–268.

Kipling, R. (1899). The white man’s burden (p. 12). New York: McClure’s Magazine.

Lenz, B. (2004). Postcolonial fiction and the outsider within: Toward a literary practice of feminist standpoint theory. NWSA Journal, 16(2), 98–120.

Lillis, K. M. (1985). Processes of secondary curriculum innovation in Kenya. Comparative Education Review, 29(1), 80–96.

Lowery, C. L. (2016). Critical transnational pedagogy. In E. J. Francois, M. B. M. Avoseh, & W. Griswold (Eds.), Perspectives in transnational higher education (pp. 55–73). Rotterdam: Sense.

Masani, Z. (2012). English or Hinglish: which will India choose? BBC News. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20500312 . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Mohanty, C. T. (1988). Under Western eyes: feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Feminist Review, 30, 61–88.

Omolewa, M. (1976). The adaptation question in Nigerian education, 1916-1936: a study of an educational experiment in secondary school examination in colonial Nigeria. Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, 8(3), 93–119.

Pieterse, J. N. (2000). After post-development. Third World Quarterly, 21(2), 175–191.

Quist, H. O. (2001). Cultural issues in secondary education development in West Africa: away from colonial survivals, towards neocolonial influences? Comparative Education, 37(3), 297–314.

Rizvi, F. (2005). International education and the production of cosmopolitan identities. RIHE International Publication Series, 9. Conference paper. Presented at the March 4th, 2005 Transnational Seminar Series at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Said, E. (1994). Orientalism. New York, NY: Random House.

Simon, D. (2006). Separated by common ground? Bringing (post)development and (post)colonialism together. Geographical Journal, 172(1), 10–21.

Sparke, M. (2007). Everywhere but always somewhere: critical geographies of the Global South. The Global South, 1(1), 117–126.

Suleri, S. (1992). Woman skin deep: feminism and the postcolonial condition. Critical Inquiry, 18(4), 756–769.

Tikly, L. (2001). Globalisation and education in the postcolonial world: towards a conceptual framework. Comparative Education, 37(2), 151–171.

Tooley, J. [Cambridge Assessment] (2014). International education: a view on what it means for developed and developing countries. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6EZmYr7-j84 . Accessed 26 June 2018.

UK Equality Act (ch. 15). (2010). Act of parliament. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/pdfs/ukpga_20100015_en.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2018.

United Nations Development Programme. (2013). Human development report.

Woolman, D. C. (2001). Educational reconstruction and post-colonial curriculum development: a comparative study of four African countries. International Education Journal, 2(5), 27–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Golding, D., Kopsick, K. The colonial legacy in Cambridge Assessment literature syllabi. Curric Perspect 39, 7–17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-018-00062-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-018-00062-0