Abstract

The evaluation and improvement of scientific terminology translation plays a crucial role in consistently and accurately communicating knowledge at an academic level as well as in applying this theoretical knowledge in practice. This becomes even more important in countries such as Greece where the majority of scientific innovations originate from other, predominately English-speaking, countries. Consequently, the dissemination of this knowledge must go through a translation process. Within this context, the author is conducting postdoctoral research in the academic field of Environmental Engineering and Hydraulics in the School of Engineering of the AUTh, Department of Civil Engineering. The research focuses on evaluating English to Greek handbooks in the academic field of Environmental Engineering and Hydraulics by using a translation control mechanism based on seven variables firstly derived from the studies of Belgian translatologist Dirk Delabastita. The outcomes so far highlighted the quality of academic and translation work, but also identified a number of translation ambiguities, different semantic variations of terms within the source text in relation to their context, the complete absence of certain terms in the translated text, and the use of an incorrect term’s translation. The evaluation of all these cases constitutes a comprehensive decision-making process that can be applied by any translator of technical texts. This process involves first evaluating the translated texts in their mother tongue and then suggesting enhanced term translations, ultimately contributing to the establishment of a more cohesive scientific consensus in Environmental Engineering terminology to implement the optimal utilization of scientific environmental methods by the Greek academic community to protect the environment, particularly in the highly sensitive Eastern Mediterranean region. Moreover, this process represents an initial step toward creating a state-of-the-art tool in teaching technical translation and lexicography to Environmental Engineering students as well as introducing foreign terminology to students in the faculty of engineering and the schools of English language and literature in the department of translation and intercultural studies, with specialization in technical translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Technical translation plays a crucial part in the ever-growing need for international cooperation in scientific, technological, and industrial activities. This tendency is even more imperative in the European Union (EU), where the availability of technical information in a variety of languages, motivated by the fact that many companies focus their activities on international markets, but also as a result of EU legislation (Byrne 2006), increases the necessity for high-quality, up-to-date, and accurate translations of technical texts. The creation of a multi-language standardized terminology in the field of Environmental Engineering aims to strengthen international scientific cooperation, firstly between the EU countries, where European legislation needs to be thoroughly understood and implemented, and then with neighboring countries outside the EU in an area such as the Eastern Mediterranean, since environmental issues know no borders and transnational scientific synergy could constitute an important factor in dealing with major environmental hazards.

The theoretical framework of the research has been thoroughly presented by Dr. Christidou in her previous papers (Christidou 2018a, b, 2020; Christidou and Kamaroudis 2019) as part of her postdoctoral research, as well as her previous academic research studies (Christidou 2008, 2014, 2017). This paper presents the theoretical framework of the research and the in-depth sequence of collecting terms from an English technical academic text, titled “Handbook of solid waste management” by Tchobanoglous and Kreith (2002) as well as the comparing and processing procedure with its Greek translation “Handbook of solid waste management” [Εγχειρίδιο διαχείρισης στερεών αποβλήτων] (2010). The extensive analysis of indexes is based on the work of Belgian translatologist Dirk Delabastita (1989), who developed translation strategies inspired by the techniques employed by ancient Latin rhetoricians, as analyzed by Heinrich Lausberg (1988) in his extensive presentation on the figures of speech used by ancient Greek rhetoricians.

Theoretical framework

Technical translation as an object of translatology

Technical translation is a type of specialized translation involving technical texts in a given field that are addressed to other experts. These texts relate to technological subject areas that deal with the practical application of scientific and technological information. Each field requires some expert knowledge and a familiarity with the subject matter. Although specialized translation is commonly considered highly complex at the level of vocabulary, without denying the key role played by this important aspect in certain text types, grammatical aspects with certain meanings also need to be interpreted and rendered in a target text (Manfredi 2014)Footnote 1.

The first professor of translation whose views are closer to technical translation is Peter Newmark. He is surely not an “extremist,” but also not a representative of the via media. Newmark generally believes that a translation theory can neither be universal nor can it turn a bad translator into a good one. It can definitely, though, reveal bad writing and bad translation, and for that reason, and at the same time, it can suggest basic principles and guidelines, some of which can be rather contradictory. Newmark draws a distinction between communicative and semantic translation. The former includes the translation of nonliterary texts and focuses on the reader and the target language. On the contrary, the latter includes the translation of literary texts and places emphasis on the source language and the source text, viewing it from a morphological and a content point of view. Ultimately, he mentions the “small”—but actually “big”—problems of translation, such as the translation of proper names, institutions, cultural meanings, and metaphors, according to him the most significant, but also of terms that until then were ignored by the various theories of translation (Newmark 1995, 2005).

The distinction of text types introduced by Newmark is intensely extended as an analytical strategy by Katharina Reiss and the typological approach that she represents. According to it, the success of the translation mainly depends on whether the translator is aware of the type of the original text and maintains the special features that condition it. The text types are grouped in three basic types: informative, expressive, and operative texts. Each one’s characteristics are clearly depicted by their name. The first type aims at conveying information, so consequently the translation focuses on the precise communication of the information content. The second type is featured by the existence of an artistic or aesthetic style, and as a result, the translation has to respect the special characteristics of the original’s form. Finally, the third type aims at persuading or dissuading, that is, convincing the reader, and as a consequence the translator’s job lies in achieving the same impact on the reader as the original (Reiss 1983).

With the description of the aforementioned features, the concept of Skopos is innate, a concept that becomes the fundamental term of Christiane Nord’s translation theory, who continues the thinking of Reiss. Nord introduces functionalist study and translation criticism. After having performed a historical retrospect and reviewing other translation theorists of functionalism, such as Hans J. Vermeer, she presents the “Theory of Action” and the “Skopostheorie/Theory of Skopos.” In the first case, translating is conceived as “intentional” and “interpersonal interaction,” as well as “communicative” and “intercultural action,” also entering the field of “text processing.” In the second case, as one can understand by its naming, the “intention” and the “aim (purpose, skopos)” of the original text are being studied as components of translation, along with the abiding relationship with the “intratextual coherenceFootnote 2”. The intratextual coherence is definitely based on the morphosyntactic rules of the target language that guide the text syntax (Nord 1997).

Werner Koller, who also forms part of the German school, comments on the multi-used concept of equivalence (Äquivalenz), placing emphasis on denotative equivalence (denotative Äquivalenz), and spots translation strategies (Übersetzungsverfahren) that consist of particular types of correspondence (Entsprechungstypen): one-to-one correspondence (Eins-zu-eins-Entsprechung), one-to-many correspondence or diversification (Eins-zu-viele-Entsprechung/Diversifikation), many-to-one correspondence or neutralization (Viele-zu-eins-Entsprechung/Neutralization), one-to-zero correspondence or blank (Eins-zu-Null-Entsprechung/Lücke), and one-to-part correspondence (Eins-zu-Teil-Entsprechung). There are five suggested ways that the translator can adopt for the one-to-zero or blank correspondence: (a) adoption of the expression in the source language from the target language, either in inverted commas without transliteration or without inverted commas with transliteration according to the phonetic, graphemic, and/or morphologic rules of the target language, (b) loan translation (Lehnübersetzung), in which expressions of the source language are translated word-for-word in the target language but the newly created expressions were not existent in the language, (c) translation of the expression in the source language from one already existing in the target language with a similar meaning, and primarily, the closest to the meaning of the original expression, (d) the expression of the source language translated with a word of explanation or annotation in the target language, and (e) adjustment or adaptation, that is, substitution of the registered expressions of the source language in specific communicative situations, with a communicative verbal unit of the target language having a function and concept similar to that of the original expression (Koller 1992).

Apparently, the aforementioned views focus on the communicative dimension of the translator. The work of Basil Hatim and Ian Mason is considered to be within this framework, as seen in its title. Moreover, they stress the communicative aspect of translation, consisting of six parameters, which, in their opinion, the translator should take into account and research: (1) cohesion,Footnote 3 (2) coherence,Footnote 4 (3) intentionality,Footnote 5 (4) situationality,Footnote 6 (5) intertextuality,Footnote 7 and (6) informativity.Footnote 8 The first two parameters concern the purely verbal aspect of translation, that is, on a morphosyntactic level, the third and fourth the social—in a broader sense—aspect, and the latter two the semantic (Hatim and Mason 1997).

Many theorists and researchers followed the functional and communicative study of translation. One of them is Delabastita (1989), on whose work is based a significant part of the study and search of our translation tool, as will be presented further on. As noted by the author (Christidou 2018b) in this case, despite the modern theoretical background, the suggested typology derives from the ancient rhetoricians. However, this is not something striking, given the fact that the art of rhetoric has a mainly communicative character, as does translation. Furthermore, this happened with renowned success—naturally, on a practical level—in the historical beginnings of translation.

All the aforementioned theories of technical translation can play a greater or lesser role in evaluation, as the latter concludes a set of different functions that can be fulfilled by implementing the theoretical framework of technical translation.

Presentation of collecting and processing terms’ procedure

Collecting of terms

Firstly, a four-column table is created. The number of rows correspond to the number of terms indexed in the technical academic text. The four columns are labeled “English term,” “Greek translation,” “Translational choice,” and “Comments–suggestions,” respectively. Each English term is recorded in alphabetical order on the basis of the index of the source text. Next to the term, the word “index” is written, followed by the number of the page on which it appears in the index, all enclosed in brackets. Afterward, the term is located within the text according to the corresponding page number listed in the index. The located terms are recorded in the first column of the table under the respective entry, and if variations of the same term are identified, they are numbered sequentially. In cases in which a composite term appears in different parts of the same sentence, the entire context is recorded. If the composite term appears in different parts of the text, it is recorded next to the term number (e.g., 2a, 2b, etc.). The recorded terms are accompanied by the chapter number, page number, and line number on which they appear. After completing the recording of the English term, the process continues with locating and recording their Greek translations. The numbering of the Greek translations corresponds with their English counterparts. If the Greek index includes additional terms not found in the original index, these are recorded separately.

Processing of terms

The subsequent stage of the process involves recording the characterization and explanation of the translation strategy employed, along with comments on the translation process.

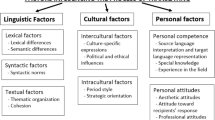

This typology includes the following translation strategies as they are presented in Table 1:

The aforementioned typology serves as a basis for studying the terms, initially as they appear in the indexes and subsequently as they appear in context within the text.

Furthermore, extensive lexicographic and bibliographic research was conducted by utilizing general and specialized dictionaries and online databases. When required, suggestions of more accurate translations were provided. The subsequent tables present a number of terms with each one of the collected and processed translation strategies, categorized accordingly.

Presentation of translation strategy examples

Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8.

Conclusions

The aforementioned lexicographical procedure aims in either preventing or correcting the existence of several scientific errors that could lead to the lack of the accuracy of content and, of course, to the ambiguity of terminology. Moreover, possible incorrect syntactic errors underline the lack of compatibility between common language and terminology. The translation manages to remain equivalent to the original text, usually in a communicative way, as it is required to achieve the same purpose, and this is obvious in its style. However, sometimes the grammar–syntactic rules of the Greek language may not be followed to a significant degree, and we can argue whether some translations would be typical of the Greek scientific literature.

As far as a general commentary regarding the processed terms is concerned, the published Greek translation can be described as an academic and translational work of high quality, where adherence to norms of the source text prevails over subscription to norms originating in the target culture (Toury 1995), thus leaning more on the translation’s adequacy rather than its acceptability by the target audience. Concerning the typological approach of the translational work (Reiss 1983), the translator is fully aware of the original text type and maintains the special features that condition it by producing an informative text type, thus focusing on the precise communication of the information content rather than respecting the special characteristics of the original’s form.

Minor linguistic problems that were traced during the term processing procedure do not alter the core of the scientific knowledge presented in the Greek translation of the book, but an adhesion to a more meticulous rendition would have covered most of the aforementioned problems. Therefore, it is advisable to include a high-skilled translatologist to the translation group when attempting to provide such an important scientific book to the Greek academic community.

The results of this research will be utilized for creating a digital bilingual scientific dictionary in the field of Environmental Engineering. This project will aid in building consensus and establishing a standardized terminology in the environmental domain, which should constitute a primary concern, especially at the university level.

Taking the aforementioned process into consideration, Dr. Christidou taught at the university level, in consultation with the professors of the Department of Civil Engineering, AUTh, some basic concepts of this translation evaluation procedure. Teaching was mainly focused on points of concern and ambiguity that occur in academic texts and their Greek translations. These teachings took place outdoors, either in landfills or in places that serve as an example of the city’s natural beauty, a fact that satisfied students immensely and tied them together as a group with common goals, namely the protection of the environment, by suggesting ways to enhance international scientific collaboration, given that the translator acts as a cultural mediator.

Notes

Translatology, in applied linguistics, is the study of translation, subsuming both interpretation of oral discourse and translation (in a narrow sense) of written discourse. The process of transferring an oral message from one language to another at the moment of utterance is variously known as simultaneous interpretation or simultaneous translation. The oral transference of a written message from one language to another is sight translation. (Crystal 2008).

A term that states that the target text makes sense within the communicative situation and culture in which it is received (Nord 1997).

The ways in which the components of the surface text, i.e., the actual words we hear or see, are mutually connected within a sequence. The surface components depend upon each other according to grammatical forms and conventions, such that cohesion rests upon grammatical dependencies (Beaugrande and Dressler 1981).

The term refers to the accessibility, relevance, and logic of the concepts and relations underlying the surface texture of a text (Munday 2009).

A feature of context that determines the appropriateness of a linguistic form to the achievement of a pragmatic purpose (Hatim and Mason 1997).

A general designation for the factors that render a text relevant to a current or recoverable situation of occurrence (Beaugrande and Dressler 1981).

The ways in which the production and reception of a given text depend upon the participants’ knowledge of other texts (Beaugrande and Dressler 1981).

The term designates the extent to which a presentation is new or unexpected for the receivers. Usually, the notion is applied to content, but occurrences in any language subsystem might be informative (Beaugrande and Dressler 1981).

References

Babiniotis G (2005) Dictionary of Modern Greek [Λεξικό της νέας ελληνικής γλώσσας]. 2nd edn. Lexicology Center [Κέντρο λεξικολογίας], Athens, ISBN 960-86190-1-7

Byrne J (2006) Technical translation - usability strategies for translating technical documentation. Springer, Netherlands, pp 2–4, ISBN: 978-1-4020-4652-0

Christidou S (2008) Translation difficulties of telecommunications academic texts (English <> Greek). Evaluation of translators’ behaviors [Μεταφραστικές δυσκολίες ακαδημαϊκών κειμένων τηλεπικοινωνιών (Αγγλική <> Ελληνική). Αξιολόγηση μεταφραστικών συμπεριφορών], Thessaloniki. Retrieved from http://invenio.lib.auth.gr/record/100715/files/gri-2008–1031.pdf. Accessed 8 Mar 2021

Christidou S (2014) Translation strategies implemented in the special fields of linguistics and telecommunications [Στρατηγικές μετάφρασης με εφαρμογή στα ειδικά πεδία της γλώσσας και των τηλεπικοινωνιών]. Dissertation, University of Western Macedonia

Christidou S (2017) At the crossroad of translation-translatology, linguistics, terminology and telecommunications – an interdisciplinary view of translation. Ostracon Publishing, Thessaloniki

Christidou S (2018a) Many roads lead to Rome, and we have found seven. A control mechanism of bilingual scientific texts translations. Babel 64 I2: 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00039.chr

Christidou S (2018b) History of translation – monograph. Stamoulis Publications, Thessaloniki, ISBN 978-618-5306-22-9

Christidou S, Kamaroudis S (2019) Implementation of the seven translation variables in the field of solid waste management as part of wastewater treatment: term investigation through the use of a psychometric questionnaire. In: Proceedings of the 7th international conference on environmental management, planning and economics (CEMEPE 2019) and SECOTOX conference, Mai 19–24, Mykonos Inland, pp 358–370, ISBN: 978-618-5271-73-2.

Christidou S (2020) Processing the creation of a bilingual scientific electronic dictionary: a first glance on the results of a lexicographical research on the field of environmental engineering. Proceedings of the sixth international symposium on green chemistry, development and circular economy conference, September 20–23, Thessaloniki, pp 256–263, ISBN: 978-618-5494-13-1

Christidou S, Kamaroudis S (2018a) Going beyond the seven roads incised by translation variables: supplementary term investigation by the use of a psychometric questionnaire. In: Proceedings of the fifth international conference on small and decentralized water and wastewater treatment plants (SWAT5), August 26–29, Thessaloniki, pp 488–498, ISBN: 978-960-243-710-0

Christidou S, Kamaroudis S (2018b) The art of compiling and sorting out the language of environmental engineering: creating a bilingual scientific dictionary. In: Theoretical aspects of lexicography and their practical implementation in the field of environmental engineering. Sixth CEMEPE and SECOTOX conference, June 25–30, Thessaloniki, pp 87–97

Crystal D (2008) A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics 6th edn. Blackwell publishing, New Jersey, p 494, ISBN: 978-1-405-15296-9

De Beaugrande R, Dressler W (1981) Introduction to text linguistics. Routledge, Oxford, ISBN 978-058-255-4856

Delabastita D (1989) Translation and mass communication: Film and T.V. translation as evidence of cultural dynamics. Babel 35 I.4: 193–218 https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.35.4.02del

Hatim B, Mason I (1997) The translator as communicator. Routledge, London, pp 14–28, ISBN: 978-041-511-7371

Koller W (1992) Einführung in die Übersetzungswissenschaft 2nd edn. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg – Wiesbaden, pp 214–236, ISBN 978-3494013794

Lausberg H (1998) A handbook of literary rhetoric. E. J. Brill, Leiden – Boston – Köln.

Manfredi M (2014) Translating text and context. Translation studies and systemic functional linguistics. From theory to practice Vol. II. Asterisco, Bologna, p 135, ISBN 978-88-96572-35-1

Munday J (2009) The Routledge companion to translation studies. Routledge, London, p 171, ISBN: 978-0-415-39641-7

Newmark P (1995) Approaches to translation. Phoenix ELT, New York, pp 38–56, ISBN 978-013-043-7952

Newmark P (2005) A textbook of translation. Longman, Essex, pp 46–47, ISBN 978-013-912-5935

Nord C (1997) Translating as a purposeful activity: functionalist approaches explained. St. Jérôme, Manchester, p 9, ISBN 978-190-065-0021

Reiss K (1983) Texttyp und Übersetzungmethode: D. operative Text. Julius Groos Verlag, Kronberg/Heidelberg, pp 18–23, ISBN 978-387-276-5093

Tchobanoglous G, Kreith F (2002) Handbook of solid waste management. 2nd edn. Mc Graw-Hill, New York, ISBN 978-007-135-6237

Tchobanoglous G, Kreith F (2010) Handbook of solid waste management [Εγχειρίδιο διαχείρισης στερεών αποβλήτων]. 2nd edn. Tziolas Publishing, Thessaloniki, ISBN 978-960-418-247-3

Toury G (1995) Descriptive translation studies and beyond. Benjamins, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, ISBN 978-902-722-4491

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. Dr. Christidou did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. No funding was received for conducting this study. No funds, grants, or other support was received. Dr. Christidou has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. Dr. Christidou certifies that she has no affiliations with nor involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. Dr. Christidou has no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Christidou has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Mohamed Ksibi.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Christidou, S. A window into the academic term control mechanism: a thorough presentation of processed terms in the process of completing an environmental science dictionary. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr 8, 753–765 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-023-00407-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-023-00407-w