Abstract

Protein–protein interactions are crucial in many biological processes. Therefore, determining the complex structure between proteins is valuable for understanding the molecular mechanism and developing drugs. Many proteins like ion channels are formed by symmetric homo-oligomers. In this study, we have proposed a hierarchical docking algorithm to predict the structure of Cn symmetric protein complexes, which is referred to as CHDOCK. The symmetric binding modes were first constructed by an FFT-based docking algorithm and then optimized by our iterative scoring function for protein–protein interactions. When tested on a symmetric protein docking benchmark of 212 homo-oligomeric complexes with Cn symmetry, CHDOCK obtained a significantly better performance in binding mode predictions than three state-of-the-art symmetric docking methods, M-ZDOCK, SAM, and SymmDock. When the top 10 predictions were considered, CHDOCK achieved a success rate of 44.81% and 72.17% for unbound docking and bound docking, respectively in comparison to those of 36.79% and 65.09% for M-ZDOCK, 31.60% and 54.25% for SAM, and 30.66% and 31.60% for SymmDock. CHDOCK is computationally efficient and can normally complete a symmetric docking calculation within 30 min. The CHDOCK can be freely accessed by a web server at http://huanglab.phys.hust.edu.cn/hsymdock/.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Protein–protein interactions are crucial in many biological processes like signal transduction, intracellular trafficking, and immune recognition. Among all protein–protein interactions, a significant portion is formed by symmetric homo-oligomers (Andre et al. 2008; Goodsell and Olson 2000; Poupon and Janin 2010). According to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al. 2000), more than one third of the proteins have some types of symmetry. For example, many transmembrane proteins like ion channels are formed by symmetric homo-oligomer assemblies. The symmetry of homo-oligomeric proteins is thought to be associated with many potential benefits like greater stability, reduced aggregation, and robustness to errors in synthesis (Andre et al. 2008; Goodsell and Olson 2000). The interface between symmetric homo-oligomers is often the targeting site for regulating the biological processes (Petsalaki and Russell 2008). Therefore, determining the complex structure of symmetric proteins is important (Lensink et al. 2016, 2018). Theoretically, one can use a general protein–protein docking approach to predict the complex structure of symmetric homo-oligomers by docking one monomer against the other (Comeau et al. 2004; de Vries et al. 2010, 2015; Torchala et al. 2013; Tovchigrechko and Vakser 2006). However, such a general docking strategy is not efficient for symmetric homo-oligomers. On one hand, the general protein–protein docking approach treats two interacting partners as different proteins and therefore often don’t generate the complex structures with strict symmetry; On the other hand, general protein–protein docking normally don’t consider the symmetry restraints during the docking process, and therefore is not computationally efficient. Therefore, specialized protein–protein docking algorithms are needed for predicting the complex structure of symmetric protein homo-oligomers.

One important symmetry in proteins is cyclic symmetry (Cn), for which the oligomeric structure can be constructed by n consecutive rotations of 360°/n around a single rotational axis of one subunit (Andre et al. 2008). Despite the importance of symmetric protein homo-oligomers, only a few algorithms have been developed for symmetric protein docking. Wolfson et al. developed a fast docking algorithm for cyclically symmetric complexes through local feature matching, which is referred to as SymmDock (Schneidman-Duhovny et al. 2005). SymmDock constructs the symmetric homo-oligomer complexes by restricting the search to symmetric cyclic transformations. The Weng group developed an FFT-based algorithm for symmetric protein–protein docking by restricting the search space with cyclic symmetry (M-ZDOCK) (Pierce et al. 2005). Based on the symmetric protein complexes in the PDB, several web servers that use template-based methods like ROBETTA (DiMaio et al. 2011), SWISS-MODEL (Biasini et al. 2014), and GalaxyGemini (Lee et al. 2013) have also been proposed to predict the homo-oligomeric structure. In addition, Ritchie and Grudinin presented a fast docking algorithm, which is named SAM, for predicting the symmetrical models of protein complexes with arbitrary point group symmetry through a spherical polar FFT-based algorithm (Ritchie and Grudinin 2016). Very recently, the Seok group has developed a combination modeling approach, GalaxyHomomer, for homo-oligomer structure prediction from a monomer sequence or structure by template-based modeling if homologous complexes are available in the PDB or ab initio docking (Baek et al. 2017).

However, despite the significant progress in the development of symmetric docking algorithms, there is still much room in improving the docking accuracy. Recently, we have developed a new pairwise shape-based scoring approach to consider long-range interactions (LSC) of protein atoms by an exponential form in FFT-based protein–protein docking. Tested on general protein–protein complexes, our LSC approach showed a significant advantage over the traditional grid-based method (Yan and Huang 2018). Extending the LSC approach to symmetric complexes, we have here developed a fast ab initio docking approach for the symmetric docking of homo-oligomers with Cn symmetry by an FFT-based search algorithm with LSC, which is referred to as CHDOCK.

Results and discussion

Comparison with other programs

We have tested our symmetric docking algorithm CHDOCK on the bound and unbound structures of our symmetric protein docking benchmark of 212 Cn targets (Yan and Huang 2019). Table 1 lists the success rates of CHDOCK in binding mode predictions for bound and unbound docking on the 212 cases with Cn symmetry when the top 1, 10, and 100 predictions are considered. The corresponding results are also shown in Fig. 1. For comparison, Table 1 and Fig. 1 also give the corresponding results of three other Cn symmetric docking algorithms, M-ZDOCK (Pierce et al. 2005), SymmDock (Schneidman-Duhovny et al. 2005), and SAM (Ritchie and Grudinin 2016), on this benchmark, in which the same clustering criteria have been applied to their final binding modes during the calculation of success rates. It can be seen from Table 1 and Fig. 1 that CHDOCK obtained a significantly better performance than the other three docking methods for bound docking and achieved a success rate of 55.19%, 72.17%, and 90.57% for top 1, 10, and 100 predictions, respectively, in comparison to those of 45.76%, 65.09%, and 89.15% for M-ZDOCK, 38.85%, 54.25%, and 84.91% for SAM, and 16.04% 31.60%, and 67.45% for SymmDock.

The success rates of our CHDOCK and three other symmetric docking methods in binding mode predictions on our protein docking benchmark of 212 Cn symmetric complexes for bound docking (A) and unbound docking (B). For each method, from left to right are for the results of top 100, 10, and 1 prediction, respectively

Similar trends can also be observed in the results for unbound docking, though the performance differences among different algorithms are not as much as those for bound docking due to the impact of conformational changes in the unbound structures. Namely, CHDOCK also performed significantly better than the other three methods for unbound docking and obtained a success rate of 30.66%, 44.81%, and 68.40% for top 1, 10, and 100 predictions, respectively, in comparison to those of 26.42%, 36.79%, and 66.51% for M-ZDOCK, 19.34%, 31.60%, and 63.68% for SAM, and 11.79%, 30.66%, and 58.49% for SymmDock (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Besides the success rate of docking, we have also compared the average root mean square deviation (RMSD) of ‘hit(s)’ (i.e., successful binding mode predictions) for both bound docking and unbound docking with the other three programs when the top 1, 10, 100 predictions were considered. The results are listed in Table 2 and the corresponding results are shown in Fig. 2. From Table 2 and Fig. 2, we can see that CHDOCK also performed much better and obtained more accurate binding modes than the other three programs for both bound docking and unbound docking. For bound docking, CHDOCK obtained an average RMSD of 1.10, 1.51 and 2.11 Å for top 1, 10 and 100 predictions, respectively, in comparison to those of 2.27, 2.80 and 3.46 Å for the second-best method M-ZDOCK. As for unbound docking, similar results can also be observed. CHDOCK obtained an average RMSD of 2.54, 3.12 and 4.07 Å for top 1, 10, 100 predictions, respectively, while M-ZDOCK obtained a higher RMSD of 3.26, 3.86 and 5.07 Å. Interestingly, one can also note that among the four docking programs, if a method performs better in the success rate of binding mode prediction, it also performs better in the average RMSD of ‘hits’. That means, the performance comes from both the number and the quality of successful predictions.

The average RMSD of first ‘hit(s)’ of our CHDOCK and three other symmetric docking methods tested on our protein docking benchmark of 212 Cn symmetric complexes for bound docking (A) and unbound docking (B). For each method, from left to right are for the results of top 100, 10, and 1 prediction, respectively

Performance of scoring function

To investigate the performance of our scoring function, we also tested our pure FFT-based docking, named CHDOCK_lite, on the benchmark, which only uses the shape complementarity to filter and sort docking poses. The docking results for bound docking and unbound docking are shown in Fig. 3. It can be seen from the figure that CHDOCK performed much better than CHDOCK_lite. With the help of our scoring function ITScorePP (Huang and Zou 2008), the success rate of bound docking for top 1 prediction increased from 21.70% to 55.19% and for unbound docking, the success rate increased from 11.32% to 30.66%. The great improvement of CHDOCK compared to CHDOCK_lite demonstrates the important role of our scoring function.

Discussions

CHDOCK and M-ZDOCK are both the three-dimensional (3D) FFT-based docking algorithms and adopt the similar sampling strategy. However, the difference between CHDOCK and M-ZDOCK is that CHDOCK adopts a better shape complementarity score LSC (Yan and Huang 2018) and a more powerful scoring function ITScorePP (Huang and Zou 2008). In our previous study on hetero protein complexes (Yan and Huang 2018), LSC has shown its better performance than PSC (Chen and Weng 2003) used in M-ZDOCK. ITScorePP also showed a better performance in scoring decoys and finding the near native structures (Huang and Zou 2008). Therefore, the better performance of CHDOCK than M-ZDOCK would be attributed to both the shape complementarity score LSC and our scoring function ITScorePP. Although CHDOCK has achieved better performance than the other three docking programs, the success rate for top 1 prediction is still not high, especially for unbound docking. There are much room to improve the existing methods and develop new docking programs in the future.

Examples of the docking model

Figure 4 shows the top binding modes predicted by our CHDOCK for both bound and unbound docking on three example targets. It can be seen from the figure that the predicted complexes overlap well with the experimental native structures, and give a ligand RMSD of 0.42 and 4.03 Å for C2 symmetric target 1MSC, 0.92 and 3.38 Å for C4 symmetric target 1OVO, and 0.95 and 1.20 Å for C6 symmetric target 1KQ1, respectively. The good consistency between the predicted and native structures in both bound and unbound docking demonstrates the reliability of our CHDOCK.

Comparisons between the top predicted binding modes and native structures for three targets 1MSC (C2 symmetry) (A), 1OVO (C4 symmetry) (B) and 1KQ1 (C6 symmetry) (C). The native structure is colored in pink and the predicted structure is colored by chains. For each column, the upper and lower ones are for bound docking and unbound docking, respectively

Conclusion

We have developed a hierarchical docking algorithm for predicting the complex structures of homo-oligomers with Cn symmetry, which referred to as CHDOCK. The Cn symmetric binding modes were first generated by an FFT-based docking algorithm, in which a shape complementarity scoring function was used to consider long-range interactions. Then, the binding modes with best shape complementarity were optimized with our iterative scoring function for protein–protein interactions. Our symmetric docking algorithm CHDOCK was evaluated on a diverse benchmark of 212 Cn symmetric protein complexes from the PDB, and was compared with three state-of-the-art symmetric docking approaches including M-ZDOCK, SAM, and SymmDock. It shows that CHDOCK achieved a significantly better performance than the other three docking methods in both the number and the quality of successful predictions for bound docking and unbound docking. The results demonstrate the strong predictive power of our hierarchical docking algorithm CHDOCK in modeling Cn symmetric protein complexes.

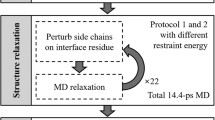

Materials and methods

FFT-based translational search

The putative symmetrical complexes were constructed from a monomer or subunit in 3D translational space by a modified version of our general FFT-based docking algorithm (Yan et al. 2017; Yan and Huang 2018). Specifically, we first made two copies of the subunit or monomer. One was called “receptor” subunit and the other “ligand” subunit. For docking with Cn symmetry, the receptor subunit was fixed and the ligand subunit was rotated by an angle of 360°/n around the z-axis. To perform an FFT-based search, both the receptor and ligand subunits needed to be mapped onto a 3D grid of \(N \times N \times N\) grid points (Chen and Weng 2003; Katchalski-Katzir et al. 1992). The grid points within the VDW radius of any protein atoms were considered inside the molecule, and the others were considered as outside the protein. Here, the VDW radii for standard protein atoms were taken from the study by Li and Nussinov (1998). Then, the inside-protein grid points were divided into three parts: surface layer, near-surface layer, and core region. It is defined that a grid point belonged to the surface layer if any of its neighboring grid points is outside the protein. Similarly, a grid point belonged to the near-surface layer if any of its neighbors is in the surface layer. All the other grid points except the surface and near-surface layers inside the protein were defined as the core region. According to the above definitions, one can see that the near-surface layer and core region were normally occupied by the protein atoms, and the surface layer separated the inside protein from the outside space. Then, each grid point for the receptor (R) and ligand (L) subunits was assigned a complex value as:

and

where \({J^2} = - 1\), l, m, and n are the indices of the 3D grid (\(l,m,n = 1, \ldots ,N\)), and r is the distance between the grid points of (i, j, k) and (l, m, n). Here, \(i \in \left[ {l - 3,l + 3} \right]\), \(j \in \left[ {m - 3,m + 3} \right]\) and \(k \in \left[ {n - 3,n + 3} \right]\) for the surface layer, and \(i \in \left[ {l - 1,l + 1} \right]\), \(j \in \left[ {m - 1,m + 1} \right]\) and \(k \in \left[ {n - 1,n + 1} \right]\) for the near-surface layer, respectively. And also, the grid point (i, j, k) should belong to near-surface layer or protein core.

With the above mapping of the proteins on the grid, the shape complementarity score between two neighboring subunits of a symmetric complex around the z-axis can be generally expressed by the following equation (Chen and Weng 2003; Katchalski-Katzir et al. 1992):

where o and p are the number of grid points by which the ligand (L) is shifted with respect to the receptor (R) in the x–y plane, respectively. There is no shift in the z-axis because the rotational axis is parallel to the z-axis, which reduces the sampling space in one translational dimension. The correlation of Eq. 3 can be calculated by an FFT-based algorithm. A higher correlation score means a better shape complementarity between two grids for a relative translation of (o, p) (Katchalski-Katzir et al. 1992).

Rotational sampling strategy

To perform a global sampling approach for putative binding modes, one needs to search the six-dimensional (i.e., 3 translational + 3 rotational) space. The exhaustive search in 3D translational space can be performed by an FFT-based approach, as described in the previous section. The exhaustive search in the rotational space will be conducted in the space of Euler angles by taking into the Cn symmetry restriction account. Specifically, the monomer subunit is rotated by an interval of Euler angles (ϕ=0, Δθ, Δψ) in the rotational space, where the angular definition is based on the so-called “x-axis convention”. Namely, \(\phi\) is the first rotation about the z-axis, \(\theta \in \left[ {0,{\uppi \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\uppi 2}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} 2}} \right]\) is the second rotation about the former x-axis (now \(x'\)), and ψ ∈ (0,2π] is the third rotation about the former z-axis (now \(z'\)). It is unnecessary to sample the ϕ angles as the rotational axis is z-axis. In addition, θ only needs to be sampled within \(\left[ {0,{\uppi \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {\uppi 2}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} 2}} \right]\) instead of \(\left[ {0,{{\pi }}} \right]\) because of the rotational symmetry. All these reduce the sampling space in the rotational space.

Then, for each rotation of the monomer subunit, an FFT-based algorithm was used to calculate the shape complementarity between the grids of the receptor and the ligand in the translational space. During the docking calculation, an angle interval of 10° was used for rotational sampling, and a spacing of 1.2 Å was adopted in discretizing proteins onto grids for FFT-based translational search. Evenly distributed Euler angles were used for the rotational search, resulting in a total of 360 orientations in the rotational space. For each rotation, up to the top 100 translations with best shape complementarities were kept and optimized by our scoring function ITScorePP (Huang and Zou 2008). The binding mode that corresponds to the best energy score in an FFT-based translational search was kept for each rotation of the ligand subunit, yielding a total of 360 ligand binding modes for a docking run. Our FFT-based docking algorithm is computationally efficient and on average can complete a full docking calculation in 30 min on a 2.6 GHZ Intel CPU core.

Scoring function

All the binding modes generated from the initial stage were evaluated by ITScorePP (Huang and Zou 2008) and minimized according to their binding scores by a SIMPLEX optimization method. The binding energy score is a summation of the binding scores over all the interfaces between the subunits of the predicted complex. The final ranked binding modes were clustered with an RMSD cutoff of 5 Å, where the RMSD was calculated using the backbone atoms. If two binding modes have a ligand RMSD of <5 Å, the one with the better score is kept.

Benchmark

Based on the protein complexes in the PDB, we have also constructed a non-redundant benchmark for our symmetric protein–protein docking. Briefly, all the homo-oligomeric protein complexes with Cn symmetry were collected from the crystal structures with resolution better than 2.5 Å. The symmetry type of a complex was determined by its biological unit. The symmetric homo-oligomer complexes were then clustered according to their SCOP (version 1.75) family IDs (Lo Conte et al. 2000). For the complexes belonging to the same family, the one with the best resolution was selected as the representative, corresponding to a bound case of our benchmark, in which each subunit was called the bound structure of the complex. For the bound structure in each bound case, the unbound structure was identified by searching against the PDB database for the asymmetric structures using the BLASTP (protein–protein BLAST) algorithm of the BLAST package (Camacho et al. 2009). If an asymmetric structure had >95% sequence identity with the bound structure and covered >95% of the sequence alignment, the asymmetric structure was regarded as a candidate of the unbound structure. If there were multiple unbound structures for a subunit protein, the one with the high resolution was selected as the representative. This yielded a total of 212 homo-oligomeric protein complexes with Cn symmetry (http://huanglab.phys.hust.edu.cn/SDBenchmark/) (Yan and Huang 2019). All the structures in the benchmark have their original coordinates without any random rotation.

Evaluation criteria

The quality of a predicted binding mode was measured by the ligand RMSD (LRMSD). Here, the RMSD was calculated based on the backbone atoms of the ligand subunit after optimal superimposition of the receptor subunit and the native structure. The docking performance was evaluated by the success rate, i.e., the fraction of the targets with at least one hit in the test set when a certain number of top predictions were considered. Here, a hit is a prediction with a ligand RMSD of <10 Å (Huang 2014).

References

Andre I, Strauss CE, Kaplan DB, Bradley P, Baker D (2008) Emergence of symmetry in homooligomeric biological assemblies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:16148–16152

Baek M, Park T, Heo L, Park C, Seok C (2017) GalaxyHomomer: a web server for protein homo-oligomer structure prediction from a monomer sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res 45:W320–W324

Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE (2000) The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28:235–242

Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Gallo Cassarino T, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, Schwede T (2014) SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W252–W258

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL (2009) BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform 10:421

Chen R, Weng Z (2003) A novel shape complementarity scoring function for protein–protein docking. Proteins 51:397–408

Comeau SR, Gatchell DW, Vajda S, Camacho CJ (2004) ClusPro: a fully automated algorithm for protein–protein docking. Nucleic Acids Res 32:W96–W99

de Vries SJ, van Dijk M, Bonvin AM (2010) The HADDOCK web server for data-driven biomolecular docking. Nat Protoc 5:883–897

de Vries SJ, Schindler CE, Chauvot de Beauchene I, Zacharias M (2015) A web interface for easy flexible protein–protein docking with ATTRACT. Biophys J 108:462–465

DiMaio F, Leaver-Fay A, Bradley P, Baker D, Andre I (2011) Modeling symmetric macromolecular structures in Rosetta3. PLoS ONE 6:e20450

Goodsell DS, Olson AJ (2000) Structural symmetry and protein function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 29:105–153

Huang S-Y (2014) Search strategies and evaluation in protein–protein docking: principles, advances and challenges. Drug Discov Today 19:1081–1096

Huang S-Y, Zou X (2008) An iterative knowledge-based scoring function for protein–protein recognition. Proteins 72:557–579

Katchalski-Katzir E, Shariv I, Eisenstein M, Friesem AA, Aflalo C, Vakser IA (1992) Molecular surface recognition: determination of geometric fit between proteins and their ligands by correlation techniques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:2195–2199

Lee H, Park H, Ko J, Seok C (2013) GalaxyGemini: a web server for protein homo-oligomer structure prediction based on similarity. Bioinformatics 29:1078–1080

Lensink MF, Velankar S, Kryshtafovych A, Huang SY, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Sali A, Segura J, Fernandez-Fuentes N, Viswanath S, Elber R (2016) Prediction of homoprotein and heteroprotein complexes by protein docking and template-based modeling: a CASP-CAPRI experiment. Proteins 84:323–348

Lensink MF, Velankar S, Baek M, Heo L, Seok C, Wodak SJ (2018) The challenge of modeling protein assemblies: the CASP12-CAPRI experiment. Proteins 86:257–273

Li AJ, Nussinov R (1998) A set of van der Waals and coulombic radii of protein atoms for molecular and solvent-accessible surface calculation, packing evaluation, and docking. Proteins 32:111–127

Lo Conte L, Ailey B, Hubbard TJ, Brenner SE, Murzin AG, Chothia C (2000) SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database. Nucleic Acids Res 28:257–259

Petsalaki E, Russell RB (2008) Peptide-mediated interactions in biological systems: new discoveries and applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol 19:344–350

Pierce B, Tong W, Weng Z (2005) M-ZDOCK: a grid-based approach for C n symmetric multimer docking. Bioinformatics 21:1472–1478

Poupon A, Janin J (2010) Analysis and prediction of protein quaternary structure. In: Data mining techniques for the life sciences. Springer, pp 349–364

Ritchie DW, Grudinin S (2016) Spherical polar Fourier assembly of protein complexes with arbitrary point group symmetry. J Appl Crystallogr 49:158–167

Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ (2005) PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W363–W367

Torchala M, Moal IH, Chaleil RA, Fernandez-Recio J, Bates PA (2013) SwarmDock: a server for flexible protein–protein docking. Bioinformatics 29:807–809

Tovchigrechko A, Vakser IA (2006) GRAMM-X public web server for protein–protein docking. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W310–W314

Yan Y, Huang S-Y (2018) Protein–protein docking with improved shape complementarity. In: International conference on intelligent computing. Springer, pp 600–605

Yan Y, Huang S-Y (2019) A non-redundant benchmark for symmetric protein docking. Big Data Min Anal 2:92–99

Yan Y, Wen Z, Wang X, Huang SY (2017) Addressing recent docking challenges: a hybrid strategy to integrate template-based and free protein–protein docking. Proteins 85:497–512

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1305800 and 2016YFC1305805), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31670724), and the startup grant of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (3004012104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Yumeng Yan, Sheng-You Huang declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Y., Huang, SY. CHDOCK: a hierarchical docking approach for modeling Cn symmetric homo-oligomeric complexes. Biophys Rep 5, 65–72 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41048-019-0088-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41048-019-0088-0