Abstract

Psychological burnout is strongly associated with negative effects on people’s life, including their emotional well-being and physical health. Due to prolonged periods of stress, heavy workloads, limited resources and time constraints, teachers are prone to burnout, leading to aversive, prolonged consequences. While previous studies have investigated various factors associated with their burnout, we explored the association between teachers’ relational and personal variables, applying a cross-sectional method. The sample consisted of 248 Israeli teachers (85.1% worked in educational settings for typically developing children, 52.4% were employed in high schools), who completed the following questionnaires: Teachers’ burnout, Perceived social support, Gratitude, Hope, Active entitlement and Loneliness. Results demonstrated negative links between burnout and social support, gratitude and hope as well as a positive link with loneliness. A serial multiple mediation revealed that, whereas social support and hope were associated with lower levels of burnout, feelings of loneliness and a sense of entitlement were related to higher levels of it. Furthermore, gratitude, hope, a sense of entitlement, and loneliness linked social support with burnout. We concluded with a discussion of the implications for future research, theory, and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Burnout is a common psychological phenomenon representing a prolonged aversive response to chronic interpersonal and situational stressors on the job. This condition is usually characterized by overwhelming exhaustion, a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of achievement due to chronic stress, excessive work demands, or exposure to challenging and emotionally draining situations (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022). Teachers’ burnout is considered a well-known and common expression of this phenomenon. Extensive research has pointed out the harmful consequences of burnout among teachers, the emotional distress it brings about, and its negative impact on their ability to fulfill their role and care for the students who depend on them (Agyapong et al., 2023). These studies have focused on the manifestations and ramifications of this phenomenon as well as on the structural characteristics of its formation (Garcia-Arroyo et al., 2019). Our goal was to identify the personal and relational factors associated with teachers’ burnout. To do so, we developed a model positing that the relational resilience factors of social support and gratitude and the personal resilience factor of hope would be associated with lower levels of teachers’ burnout. In addition, according to this model, teachers’ loneliness might be linked to higher levels of burnout. The relationship between sense of entitlement and burnout remains open-ended.

1 Teachers’ Burnout

Psychological burnout, often referred to simply as "burnout," is a state of chronic emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by excessive and prolonged stress. It is primarily associated with the workplace or prolonged periods of stress and is not simply a result of being tired or overworked for a short period (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022). According to Maslach (1998), one of the key theories in the field, burnout occurs when there is a high level of emotional exhaustion, coupled with a strong sense of depersonalization and lack of personal accomplishment. These components are interrelated and influence each other (Ozturk, 2020). Burnout is often associated with high-stress environments, excessive workloads, lack of control or autonomy, unclear job expectations and inadequate support systems (Alarcon, 2011; Mijakoski et al., 2022). Burnout can affect various aspects of people’s lives, including their emotional well-being, physical health, sense of accomplishment and overall quality of life (Nadon et al., 2022). It can also impact both their physical and mental health, leading to various symptoms (Lyndon et al., 2017). Examples include chronic illness, sleep disturbances, changes in appetite, anxiety and depression (Edú-Valsania et al., 2022; Madigan, et al., 2023).

Accordingly, teachers’ burnout is a complex phenomenon that occurs when educators experience physical, emotional and mental exhaustion due to prolonged and excessive stress associated with their profession (Maslach et al., 2001). This phenomenon can have serious consequences for both teachers and students, as it affects the overall quality of education and the wellbeing of those involved (Agyapong et al., 2022; Madigan & Kim, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2023). The literature has identified several factors that contribute to teachers’ burnout. For example, teachers’ heavy workloads, coupled with limited resources and time constraints, may be detrimental, especially when teachers are expected to meet high standards in terms of students’ achievement and classroom management (Madigan et al., 2021). Additionally, managing diverse classrooms with students of various learning abilities, backgrounds, and needs can be challenging (Park & Shin, 2020). Teachers’ lack of autonomy may also lead to frustration, as they experience limited control over curriculum decisions (Agyapong et al., 2023). Finally, dealing with students’ emotional and behavioral challenges may take a toll on teachers, contributing to their burnout (Agyapong et al., 2022; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2020).

2 Gender Related Teacher Burnout

Some studies have explored the personal factors that may account for teachers’ burnout. For example, research has looked at gender as a possible variable, with mixed findings. Some studies have found gender differences in the vulnerability to burnout (Garcia-Arroyo et al., 2019; Kasalak & Dağyar, 2021; Pavlidou et al., 2022), while others have not (Jamaludin & You, 2019; Răducu & Stănculescu, 2022). One of the explanations regarding these mixed results posited that while burnout is present among men and women, its expression may be different, making it challenging to identify and address gender sensitivity to burnout (Innstrand et al., 2011). Whereas women teachers may be more likely to internalize their stress and emotional exhaustion, leading to symptoms such as depression and anxiety, men teachers may exhibit more externalizing behaviors, such as increased absenteeism or frustration with students (Pavlidou et al., 2022). Other researchers, however, suggested that gender-related factors may override each other. For instance, as the usual primary caregivers in their families, women teachers may face unique challenges related to their work-life balance. Adding these challenges to social expectations and gender roles might increase the stress that women teachers must deal with, making them potential candidates for burnout (Wei & Ye, 2022). Alternatively, Zhang et al. (2022) suggested that, compared with men teachers, women teachers may look more favorably on the school’s culture and manage their emotions more proactively to maintain their relationships in the school, work collaboratively with others and actively seek consensus in the school.

In order to extend the research on teachers’ burnout, we focused attention on the interpersonal and intrapersonal factors associated with levels of burnout, while taking into account well-established demographic variables such as gender within this field. Thus, we developed a model exploring the links between the teachers’ perceived social support, gratitude, hope, sense of entitlement, and loneliness in their work and the degree to which they felt burned out.

3 Social Support

Social support refers to the assistance, care, and comfort that people provide to one another. It can come from various sources, including family, friends, coworkers, and community groups. One prominent framework within social support theory is the stress-buffering model (Cohen & Wills, 1985) suggesting that social support acts as a buffer or protective factor against the negative impact of stress on an individual's well-being. According to this model, social support helps individuals cope with stress by providing emotional, instrumental, or informational resources. The presence of supportive others can alter the perception of stress and enhance one's ability to manage and cope with challenging situations. The effectiveness of social support as a buffer may be influenced by various factors, including the type of support, the quality of the relationship, and individual characteristics (Cohen & McKay, 2020; Szkody et al., 2021). Accordingly, past research suggested that perceived social support plays a crucial role in maintaining emotional well-being, coping with stress, and navigating life's challenges (Harandi et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). Perceptions about social support have been linked repeatedly to various benefits, including feeling less isolated, lonely, and depressed. These perceptions also improve people’s ability to deal with traumatic events, illnesses or life changes. They also help people make more informed decisions and improve their problem-solving skills (Brooks et al., 2019; Kelly et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018).

Given these beneficial effects of perceived social support, it is not surprising that previous studies have indicated the significant links between social support and teachers’ burnout. These studies suggest that the ability to rely on colleagues, share the difficulties and challenges of the profession with other members of the educational staff (i.e., support within the educational framework, meaning internal support), as well as receive reassurance and encouragement from family members and friends (i.e., support outside the educational framework, meaning external support) may reduce burnout and protect against its adverse consequences (Fiorilli et al., 2017, 2019; Marcionetti & Castelli, 2023). Thus, we included the perception of social support as an independent factor in our proposed model.

4 Gratitude

Gratitude is defined as the ability to appreciate the positive aspects of one’s life, whether significant and central or incidental and limited. It is an emotional response that arises when individuals recognize and acknowledge the assistance, consideration, and support they have received from others or from various circumstances (Jans-Beken et al., 2020; Portocarrero et al., 2020). One key theory related to gratitude is the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, proposed by Fredrickson (2004). While this theory does not focus exclusively on gratitude, it provides a framework for understanding how positive emotions, including gratitude, contribute to overall well-being. According to the theory’s premise, gratitude is a positive emotion that broadens people’s outlook, making them more likely to notice and appreciate positive aspects of their lives, and fostering a broader and more inclusive perspective. Over time, the experience of gratitude is believed to help people build personal resources, develop positive coping mechanisms and reinforce patterns of positive thinking (Xiang & Yuan, 2021; Yang et al., 2023). Indeed, research has indicated that cultivating a sense of gratitude can help shift one’s focus away from negativity and pessimism and promote a more positive and contented mindset (Portocarrero et al., 2020). Accordingly, practicing gratitude has been linked to various psychological, emotional, and even physical benefits, including improved affect, a sense that one’s life is meaningful, a reduction in stress, and better overall well-being (Confino et al., 2023; Deichert et al., 2021).

Extensive research has been conducted on the proactive, even preventive, effects of gratitude on reducing burnout in a wide variety of professions including medical teams, athletes, and students (Camero & Carrico, 2022; Ruser et al., 2020; Yukhymenko-Lescroart, 2022). For instance, a study by Guan and Jepsen (2020) identified gratitude as a positive resource for healthcare teams, buffering the effects of cognitive overload on emotional exhaustion and the effects of response modulation on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Similar findings have been observed within the realm of teaching (Chesak et al., 2019; Turinas et al., 2023). For example, a systematic review of school-based positive psychology interventions, which included interventions dealing with gratitude, outlined the proactive and preventative strategies that teachers could learn to use to help them cope with the demands of the profession and reduce the likelihood of their burnout (Vo & Allen, 2022).

5 Hope

Hope refers to a fundamental human cognition with accompanying emotions that helps individuals cope with challenges, setbacks and uncertainty. Hope can play a significant role in maintaining people’s mental and emotional wellbeing as it provides a sense of purpose and direction, even during turbulent times (Pleeging et al., 2021). Thus, we were guided in our study by Snyder’s (2002) theory of hope as a cognitive process that drives motivation and goal attainment. This theory suggests that hope consists of two main components: agency thinking, meaning the ability to engage in intentional actions, make choices, and exert control over their environment, and pathways thinking, which refers to the ability to identify and create feasible routes to achieve one’s goals. Hope, according to Snyder (2002), emerges when these two components are combined. People with high levels of hope tend to set clear goals, develop multiple strategies to achieve them, and maintain a strong belief in their ability to navigate challenges and obstacles (Gallagher & Lopez, 2018).

Research based on hope theory suggests that hope has positive effects on various aspects of life, including academic achievement, coping with illness, managing stress, and pursuing personal and professional goals (Cheavens et al., 2019; Duncan et al., 2021; Einav & Margalit, 2022). Scholars have also suggested that maintaining a hopeful outlook can improve people’s emotional well-being and resilience, which in turn can help prevent or alleviate burnout (Duncan & Hellman, 2020; Gungor, 2019; Pharris et al., 2022). Similarly, teachers who reported high levels of efficacy, optimism, resilience and hope also reported the lowest levels of burnout (Ferradás et al., 2019).

6 Sense of Entitlement

A sense of entitlement is the belief or expectation that one is deserving of special treatment, privileges, or advantages without necessarily having earned them through one’s actions or efforts (Jordan et al., 2017). Studies have investigated the role of a sense of entitlement as a risk factor or a form of resilience. Those who feel entitled often have attitudes and engage in behaviors based on the sense that they are owed something, and feel frustrated when these expectations are not met (Grubbs & Exline, 2016; Lange et al., 2019; Li, 2021). Nevertheless, other studies have pointed out the beneficial aspects of a having a sense of entitlement. These studies maintain that such feelings promote self-advocacy, efficacy, and assertiveness, encouraging a more balanced perspective on personal rights and responsibilities. They concluded that a sense of entitlement can be an important coping resource (Brant & Castro, 2019; Confino et al., 2023; George-Levi & Laslo-Roth, 2021).

Piotrowski and Żemojtel-Piotrowska (2009) proposed a model of the sense of entitlement consisting of three forms: active entitlement, based on the protection of one’s self-interests; passive entitlement, which focuses on the conviction that institutions and organizations are obligated to satisfy one’s needs, and revenge entitlement, based on the protection of one’s self-interests when they are threatened or violated. Out of the three, active entitlement seems to be a proactive and an agentic aspect of psychological wellbeing, and thus regarded as a resilience factor. Research has confirmed this hypothesis, establishing a positive relationship between active entitlement and subjective wellbeing (Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al., 2017), hope and satisfaction with life (George-Levi and Laslo-Roth, 2021), and growth after suffering a trauma (Confino et al., 2023).

However, surprisingly, there is relatively little research on the links between a sense of entitlement and burnout. The few studies that have been conducted deal with the contribution of “third-party” entitled parties such as customers (Fisk & Neville, 2011; Kim et al., 2021; Ouyang et al., 2022) or students (Jiang et el., 2017) to employees’ burnout. To the best of our knowledge, to date, no one has examined the link between a sense of entitlement and burnout among teachers.

While the variables reviewed thus far might be linked to reduced levels of teachers’ burnout, we posit that there is one factor that can be associated with higher levels of teachers’ burnout—loneliness.

7 Loneliness

Known for its harmful effects, loneliness is a complex and often distressing emotional state that arises when a person feels isolated or disconnected from others. Research has indicated that loneliness is not about being physically alone. Rather, it is more of a feeling of lack of meaningful social connections or the perception that one’s social needs are not being met (Peplau, 1985). One key theory in the study of loneliness is the social cognitive theory of loneliness developed by Cacioppo and Patrick (2008). This theory suggests that loneliness arises from a combination of social and cognitive factors. Specifically, perceived social isolation is triggered by cognitive biases such as negative expectations about social interactions, heightened sensitivity to social threats, or a tendency to interpret ambiguous social cues in a negative way. This theory also posits that social interactions provide rewards that are crucial for well-being. Loneliness may result from a lack of these social rewards, leading to a cycle where individuals withdraw further from social interactions (Cacioppo et al., 2015).

Research has suggested that loneliness can be caused by various factors, such as separation, lack of close relationships, social isolation, major life changes such as moving to a new place or losing a loved one, and even the rise of social media, which can sometimes lead to feelings of inadequacy or upward comparisons (MacDonald et al., 2020). Prolonged loneliness can have negative impacts on people’s mental, emotional, and physical health. It has been linked to increased stress, depression, anxiety, and even certain physical health problems (Barjaková et al., 2023; Dahlberg et al., 2022; Heinrich & Gullone, 2006).

Therefore, it is not surprising that a significant amount of research has examined the relationship between loneliness and burnout, citing teachers as a population at risk (Fornaciari, 2019; Hosseini et al., 2023; Lan et al., 2019). Thus, experiencing loneliness can result in several negative outcomes such as lack of emotional outlets, a limited number of coping mechanisms, feeling more stressed, lack of a work-life balance, and the absence of social recognition, which may be associated with increased burnout in teachers (Eryılmaz & Kara, 2021; Tvedt et al., 2021).

8 Current Research

Extensive research has pointed out the harmful consequences of burnout among teachers, the emotional distress it brings about, and the way it negatively affects their ability to fulfill their role adequately and care for the students who depend on them. In this regard, teachers in Israel are no different from the international community of teachers (Fisherman, 2016). Research in this field has focused on the nature of this phenomenon, its mental and emotional ramifications among those in the educational system, as well as the underlying structural characteristics of burnout such as the educational setting and restraints on learning outcomes.

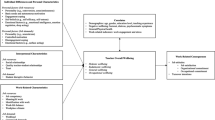

We present a comprehensive model in which we hypothesize that (H1) the interpersonal factor of social support and the intrapersonal factors of gratitude and hope may be associated with lower levels of teachers’ burnout. In addition, the model posits that (H2) loneliness will be related to higher levels of burnout. We leave the association between burnout and the sense of entitlement as an open question. Lastly, we hypothesize that (H3) the relationship between perceived social support and burnout will be linked by gratitude, hope, a sense of entitlement and loneliness.

9 Method

9.1 Participants

To test our hypotheses, we recruited a sample of Jewish Israelis currently working as teachers via an Israeli-based sampling service, “Ipanel.” Their participation was voluntary, and the participants were compensated for filling out the survey. Data was collected during January 2023. Out of the 250 participants who completed the survey, we excluded one participant who did not identify as Jewish and another who had taken the survey twice.

The final sample consisted of 248 Israeli teachers (169 women and 79 men) ranging in age from 24 to 74 years old (M = 44.47, SD = 11.72). Almost all of the participants (94%) had an academic degree or equivalent, with 43% holding an M.A degree or above. The vast majority of the participants (85.1%) worked in educational settings for typically developing children, while the rest (14.9%) worked in special education settings. Almost half of the participants (47.6%) worked in elementary schools, and the rest (52.4%) were employed in high schools. They had worked in their current educational setting for 1 year to 48 years (M = 14.97, SD = 11.06). Comparing the men and women teachers with regard to their age and seniority did not yield any significant differences. We conducted a sensitivity power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) for linear multiple regressions. A random model, including the five factors (assuming an α of 0.05, two-tailed; and a power of 0.80) revealed that the final sample (N = 248) had sufficient power to detect a small-sized effect of R2 = 0.0.059.

10 Measures

10.1 Social Support

To assess social support, we used the Hebrew adaptation (Statman, 1995) of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS;; Zimet et al., 1988). The scale consists of three subscales: perceived support from peers (“I can rely on my friends when I have problems”), from family (“My family truly tries to help me”), and from significant others (“There is someone close to my heart with whom I can share both happiness and sorrow”). The scale entails 12 items ranked on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). In the current study, the measure demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.940.

10.2 Gratitude

To measure feeling grateful across situations, we used the Hebrew adaptation (Zimmerman, 2011) of the Gratitude Questionnaire– 6 (GQ-6; McCullough et al., 2002;). This scale has six items (e.g., “I have so much in life to be thankful for”) ranked on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In the current study, the measure demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of.772.

10.3 Hope

To assess levels of hopeful thinking, the Hebrew adaptation (Lackaye & Margalit, 2006) of the Trait Hope Scale (Snyder, 2002) was used. The scale includes six items (e.g., “I can achieve most of my goals”) ranked on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Cronbach’s α reliability for the scale in the current study was.890.

10.4 Sense of Entitlement

To assess participants’ beliefs regarding their sense of entitlement, we used The Entitlement Questionnaire – Short Form (Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al., 2017). Although the original scale consists of 15 items, we included only the active sense of entitlement subscale in its Hebrew version (Confino et al., 2023) whose five items deal with one’s self-interests and self-reliance in achieving life’s goals (e.g., “I deserve the best”). The items are ranked on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). For the current study, the measure demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of.724.

10.5 Loneliness

To assess subjective feelings of loneliness, we used a 4-item adapted loneliness scale (based on Hughes et al., 2004). The scale retains three core items from Hughes et al. that measure perceptions of loneliness (e.g., “I feel alone”) ranked on a 1 (never) to 4 (often) Likert scale. Mund et al. (2022) added another item – “I am lonely” – to Hughes et al.’s (2004) original 3-item scale. Prior research has established a strong correlation (r = 0.82) between the brief 3-item version and the original 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980), supporting its validity as a concise measure of loneliness. In the current study, the 4-item measure demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.881.

10.6 Teachers’ Burnout

To assess teachers’ burnout, we used the Hebrew adaptation (Friedman, 2003) of the 14-item Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) This adapted scale includes Likert-type frequency items ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always) relevant over the past 2–3 months, such as “I feel that teaching is tiring me too much.” After reversed coding the item, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis indicating that all of the items except for the reversed item loaded on a single factor. We therefore computed the mean of the entire scale. In the current study, the measure demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.927.

10.7 Demographics

We asked the participants about their age, gender, level of education, marital and parental status. In addition, we asked about their seniority in their current educational setting, roles in school, type of educational setting (elementary or high school), and employment in regular or special education.

11 Procedure

The participants were invited to fill out the survey that was administered online via Qualtrics. The participants received a small monetary compensation for their participation. Prior to their participation, the participants signed a consent form that explained that their responses would be anonymous. They were also provided with the contact information of the first author. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s institution.

12 Data Analysis

We conducted the analyses using IBM SPSS 29 for Windows with maximum likelihood estimation. Initially, we performed preliminary analyses including bivariate correlations to examine the associations among the research measures, as well as a MANOVA to explore gender differences. Following these analyses, we conducted a multiple hierarchical regression analysis to test the relative contributions of the interpersonal factors (social support, sense of entitlement) and the intrapersonal factors (hope, gratitude and loneliness) in accounting for variance in the teachers’ burnout. To control for the demographic variables (age, gender, parenthood, type of education (regular/special), type of educational setting (elementary/high school), role in the school, and seniority), we included these variables in the model in the first step. In the second step, we added the interpersonal factors to test their role in explaining the dependent variable. In the third step, the intrapersonal factors were entered.

Next, to explore the relationships among the variables and to identify any mediating paths, we used Hayes’s (2018) bootstrapping approach. We utilized Hayes’ PROCESS 4.0 macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2018; Model 6) and Preacher and Hayes’s (2008) bootstrapping method with 5000 resamples with replacement. We chose bootstrapping because it provides a more reliable estimate of indirect association, does not assume normality and evaluates total, direct and indirect association (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Bootstrapping also has higher power and better type I error control than other mediation analyses. It tests the intervening variables’ indirect association as a whole model and does not require the interpretation of each path. We determined significance by examining the 95% confidence interval produced by the bootstrapping mediation analyses. In order for the mediation model to attain significance, the confidence interval must not include zero. This approach has two advantages over alternative methods of testing mediation. First, multiple mediating variables can be assessed simultaneously. Second, bootstrapping methods were used to generate confidence intervals for estimates of the products of the model coefficients for the indirect or mediated associations. In this analysis social support was the independent variable, teachers’ burnout was the dependent variable, and gratitude, hope, entitlement and loneliness were the mediators. We also controlled for the participants’ age and gender. Statistical significance was considered at P-value < 0.05.

Before turning to the results, it is important to add a word of caution about the language that we used in reporting the findings of our study. We discuss the results in terms of associations due to the correlational nature of the data.

13 Results

First, we calculated the bivariate correlations between the research variables. As expected, the results, which appear in Table 1, showed that social support, gratitude, and hope were negatively associated with burnout. Loneliness was positively associated with burnout and negatively associated with the remaining factors. Taking into consideration the possible role of gender, we conducted a MANOVA, in which the independent variable was the participant’s gender and the dependent variables were burnout, social support, gratitude, hope, sense of entitlement, and loneliness. According to Wilk’s Lambda, there was a main effect for gender, F (6, 241) = 3.25, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.075. Separate univariate ANOVAs revealed significant main effect for gender in hope F(1, 246) = 4.03, p = 0.046, η2 = 0.016 and burnout, F(1, 246) = 10.30, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.040, suggesting that women teachers were less hopeful (M = 4.30, SD = 0.80) and experienced more burnout (M = 3.50, SD = 0.94) than men teachers (M = 4.51, SD = 0.73, M = 3.08, SD = 1.03, respectively).

14 Stepwise Multiple Hierarchical Regressions

We examined whether the research variables were associated with the participants’ degree of burnout. We therefore conducted a stepwise multiple hierarchical regression. In the first step we entered the unstandardized scores on the demographic variables (age, gender, parenthood), type of education (regular/special), type of educational setting (elementary/high school), role in the school, and seniority The analysis revealed R2 = 0.110, Cohen’s f2 = 0.124 with a significant positive association with gender, indicating that women reported higher levels of burnout (B = 0.44, SE = 0.13, t = 3.28, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.174, 0.700]. No other significant association was found.

In the second step, we added perceived social support and sense of entitlement to the analysis. The results of R2 = 0.161, R2 (change) = 0.051, Cohen’s f2 = 0.192) suggested that burnout had significantly negative associations with age (B = -0.018, SE = 0.009, t = -2.12, p = 0.035, 95% CI [-0.036, -0.001]) and with social support (B = -0.19, SE = 0.06, t = -3.35, p = 0.001, 95% CI [-0.308, -0.080]), indicating that older teachers who perceived high level of social support, experienced less burnout. In addition, the association with gender remained significant (B = 0.45, SE = 0.13, t = 3.48, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.196, 0.709]). The association between burnout and a sense of entitlement was not significant (B = 0.13, SE = 0.07, t = 1.83, p = 0.068, 95% CI [-0.010, 0.262).

In the third step, we added hope, gratitude, and loneliness to the analysis. The analysis of R2 = 0.267, R2 (change) = 0.106, Cohen’s f2 = 0.364 suggested that burnout had a significant association with type of education (B = -0.35, SE = 0.16, t = -2.18, p = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.665, -0.033]). Thus, those who teach in regular education settings experienced more burnout than teachers in special education settings. In addition, burnout had a significantly negative association with age (B = -0.02, SE = 0.01, t = -2.77, p = 0.006, 95% CI [-0.039, -0.007]). The positive association with gender (B = 0.35, SE = 0.13, t = 2.74, p = 0.007, 95% CI [0.097, 0.593]) remained significant. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that burnout had a significantly positive association with sense of entitlement (B = 0.18, SE = 0.07, t = 2.66, p = 0.008, 95% CI [0.047, 0.312]), a negative association with gratitude (B = -0.20, SE = 0.07, t = -2.66, p = 0.008, 95% CI [-0.343, -0.051]), a positive association with loneliness (B = 0.26, SE = 0.09, t = 2.92, p = 0.004., 95% CI [0.086, 0.441]), and a negative association hope (B = -0.24, SE = 0.08, t = -2.87, p = 0.004, 95% CI [-0.404, -0.075]). Thus, younger women who teach in regular education schools, who felt more entitled, lonelier, less hopeful and less grateful reported higher levels of burnout. At this step, the association of burnout with social support was no longer significant (B = 0.02, SE = 0.07, t = 0.36, p = 0.72, 95% CI [-0.107, 0.155]). The third step of the regression explained 26.7% of the variance in burnout – F (12,232) = 7.05, p < 0.001.

15 Mediation Analyses

In order to further examine whether the intrapersonal factors of gratitude and hope and the interpersonal factors of sense of entitlement and loneliness could account for the link between perceived social support and burnout, we conducted a serial multiple mediation analysis. We did so by using model 6 in Hayes (2018) to identify any indirect associations, with gender and age as the covariates. We tested the mediation analyses using the bootstrapping method, with bias-corrected confidence estimates (MacKinnon, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). This approach yielded a 95% confidence interval of the indirect associations with 5,000 bootstrap resamples (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

As Table 2 and Fig. 1 indicate, the total association of perceived social support with burnout was significant. In addition, gratitude connected the link between perceived social support and hope. Furthermore, hope and loneliness connected the link between perceived social support and burnout. Finally, entitlement and loneliness connected the link between hope and burnout. The remaining paths were not significant.

Given that we entered perceived social support and the four mediating variables into the equation simultaneously, the link between perceived social support and burnout was weakened and did not remain significant. Thus, we concluded that the link between support and burnout was not only direct, but also indirect, through hope and loneliness. In addition, the link between gratitude and entitlement was explained indirectly, through hope. The overall model was significant, F (3, 243) = 11.20, p < 0.001, explaining 34.9% of the total variance.

16 Discussion

Teachers’ burnout is a serious, multifaceted problem with wide-ranging effects (Lyndon et al., 2017; Nadon et al., 2022). Many studies deal with the factors that exacerbate this phenomenon or provide strategies to address it (Madigan and Kim, 2021; Park and Shin, 2020). With a growing understanding of the complexity of this phenomenon, the purpose of the current study was to map the key factors associated with burnout, specifically those linked to resilience and risk, and identifying the potential links between them.

In line with past research, perceived social support and hope were related to lower levels of burnout, whereas loneliness was related to higher levels of it. This pattern of findings supports previous studies suggesting social support and hope as resilience factors that strengthen the teachers’ ability to face the ongoing challenges of teaching (Ferradás et al., 2019; Marcionetti and Castelli, 2023). These findings also accord with Maslach (1998), suggesting that the presence of supportive others, intertwined with a hopeful outlook on the future, may counteract each of the factors involved in burnout- emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a sense of lack of accomplishment. In contrast, those who felt lonely were less able to deal with the demands of the job and fight burnout (Eryılmaz and Kara, 2021). Therefore, we suggest that the ability to share the difficulties and challenges inherent in the profession with a supportive social network and maintain a sense of purpose and direction, even during turbulent times, helps teachers avoid burnout and function according to their own expectations as well as those of the systems around them. Alternatively, feeling isolated, disconnected or even depersonalized makes it more difficult for teachers to deal with the daily challenges presented by students, parents, and the educational system.

Earlier studies presented inconsistent results regarding the role of a sense of entitlement in people’s work, because the interpretation of “entitlement” depends on the specific context in which it is used. Thus, it can have positive or negative connotations depending on the situation (Brant and Castro, 2019; Lange et al., 2019). In addition, to the best of our knowledge, to date, no research has investigated its role in burnout. Our results indicated that a sense of active entitlement is associated with intensified levels of teachers’ burnout. Therefore, in our study, feelings of active entitlement may have been linked to the notion that they are being deprived of their rights and do not receive the consideration or recognition from others that they deserve. Considering the limited research about the relationship between a sense of entitlement and teachers’ burnout, we encourage future studies to explore how we can use entitlement, and active entitlement specifically, to promote proactive actions that will have a positive effect on teachers, empowering them to pursue their goals even when faced with ongoing challenges or obstacles.

The perception of social support, one of the key variables previously linked to burnout, has important interrelationships with the remaining variables we explored. In fact, as was noted previously, once other variables were entered to the equation, social support lost its significance. Specifically, social support was associated with higher levels of hope, which were then linked to lower levels of burnout as well as reduced loneliness, which, as expected, was related to increased burnout. In addition, perceived social support was associated with increased gratitude, which in turn was related to increased hope and reduced burnout. These interrelated links provide additional support for the stress-buffering model of social support (Cohen and Wills, 1985), suggesting that the resources provided by others associated with hope, gratitude and reduced loneliness may help buffer the stress inherent in burnout. Moreover, these mediation paths, despite the indisputable importance of social support in reduced burnout, underscored the value of personal and interpersonal variables. Thus, the study demonstrated the importance of the personal factors of hope and gratitude and the interpersonal factor of loneliness in the teachers’ ability to fight burnout. Together, these findings suggest that future studies could examine if providing social support through activities such as corporate events or team retreats should be accompanied by reducing stress and strengthening the individual and interpersonal characteristics of the teacher, through which social support acts.

Of the key factors in the proposed model, hope plays a central role. The extensive direct and indirect links between hope and burnout confirm and reinforce previous research in the field. These links, clearly articulated in Snyder (2002), emphasize the vital importance of hope in the ability to anticipate the future, set goals, and plan ways of achieving them (Duncan and Hellman, 2020; Gungor, 2019; Pharris et al., 2022). Burnout makes it difficult for teachers to deal with frequent, recurring challenges. Therefore, those who can look ahead, set goals, and have a sense of purpose and meaning are best positioned to ward off burnout.

Finally, gender is a consistent factor in predicting burnout, with women teachers reporting higher levels of burnout than men teachers. This finding joins a long line of studies on the subject, some of which indicate gender as a relevant factor in burnout (Kasalak and Dağyar, 2021; Pavlidou et al., 2022), while others do not (Răducu and Stănculescu, 2022). Note that gender also was associated with hope, a factor that was related to burnout, again in the same direction. It can therefore be assumed that if women teachers are indeed less hopeful, they are more likely than their men counterparts to experience burnout, together with its detrimental ramifications.

17 Limitations and Future Directions for Research

Our findings should be interpreted with caution, in view of several methodological limitations. First, our questionnaires are based on self-reports, reflecting mostly the participants’ conscious, possibly desired, image of themselves and their experience. Although people’s subjective perceptions affect various experiences in their lives (Bellemare, 2009), specifically perceived social support and burnout, other, less mindful aspects may also have an impact. Given the limitations regarding causal inferences embedded in cross-sectional designs, future research can use longitudinal studies with a more heterogeneous sample and mixed methods such as interviews or observations to investigation teachers’ burnout.

Regarding the current findings, gender differences in burnout require further examination. Researchers could explore the pathways through which they operate, particularly given the fact that women make up the majority of teachers. In addition, studies could investigate the links between a sense of entitlement and burnout in more depth, specifically for teachers and those in other high-risk professions. As mentioned, while sense of entitlement has been viewed in some studies as an important resource (Confino et al., 2023; George-Levi and Laslo-Roth, 2021), in the context of burnout it may be linked to overwhelming feelings of frustration and helplessness in the face of a reality that teachers regard as uncontrollable or unfavorable.

Finally, despite the fact that our findings shed light on our understanding of the factors that are associated with burnout, the phenomenon itself is a complex one composed of various aspects (Greenglass et al., 1998; Maslach et al., 2001) that future studies may address. For instance, focusing on individual characteristics such as emotional fatigue, pessimism, or alternately, personal advocacy, together with structural characteristics such as the school’s climate or policies may provide valuable insights into this phenomenon.

18 Summary and Clinical Implications

Many countries face an acute shortage of teachers (Wiggan et al., 2021). In addition, teachers sometimes remain in their jobs even after feeling burned out, with harmful consequences for all those around them (Nguyen and Springer, 2023). Thus, there are numerous reasons for identifying the factors that are associated with teachers’ burnout and using that information to help teachers to cope better. Based on our findings, we recommend several approaches to achieving this goal. Providing mentoring-based intervention programs for novice teachers, and strengthening mutual relationships among the teaching staff via support groups and peer learning could be helpful in promoting social support and alleviating loneliness. In addition, developing workshops that strengthen hopeful language and hopeful thinking about the future, already in place with regard to students (Rosenstreich et al., 2015) and parents (Einav & Margalit, 2019), combined with practicing a grateful outlook regarding the present, may strengthen the teachers’ personal resilience and provide them with the tools they need to face the challenges of the profession.

References

Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710706

Agyapong, B., Brett-MacLean, P., Burback, L., Agyapong, V. I. O., & Wei, Y. (2023). Interventions to reduce stress and burnout among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(9), 5625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095625

Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007

Barjaková, M., Garnero, A., & d’Hombres, B. (2023). Risk factors for loneliness: A literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 116163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116163

Bellemare, M. F. (2009). When perception is reality: Subjective expectations and contracting. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 91(5), 1377–1381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2009.01351.x

Brant, K. K., & Castro, S. L. (2019). You can’t ignore millennials: Needed changes and a new way forward in entitlement research. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(4), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12262

Brooks, M., Graham-Kevan, N., Robinson, S., & Lowe, M. (2019). Trauma characteristics and posttraumatic growth: The mediating role of avoidance coping, intrusive thoughts, and social support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(2), 232. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000372.supp

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. WW Norton & Company.

Camero, I., & Carrico, C. (2022). Addressing nursing personnel burnout in long-term care: Implementation of a gratitude journal. Holistic Nursing Practice, 36(3), E12–E17. https://doi.org/10.1097/hnp.0000000000000512

Cheavens, J. S., Heiy, J. E., Feldman, D. B., Benitez, C., & Rand, K. L. (2019). Hope, goals, and pathways: Further validating the hope scale with observer ratings. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 452–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484937

Chesak, S. S., Khalsa, T. K., Bhagra, A., Jenkins, S. M., Bauer, B. A., & Sood, A. (2019). Stress management and resiliency training for public school teachers and staff: A novel intervention to enhance resilience and positively impact student interactions. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 37, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.08.001

Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (2020). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In Handbook of psychology and health, Volume IV (pp. 253–267). Routledge.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Confino, D., Einav, M., & Margalit, M. (2023). Post-traumatic Growth: The roles of sense of entitlement, gratitude and hope. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00102-9

Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J., Frank, A., & Naseer, M. (2022). A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 26(2), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638

Deichert, N. T., Fekete, E. M., & Craven, M. (2021). Gratitude enhances the beneficial effects of social support on psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(2), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1689425

Duncan, A. R., Jaini, P. A., & Hellman, C. M. (2021). Positive psychology and hope as lifestyle medicine modalities in the therapeutic encounter: A narrative review. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 15(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827620908255

Duncan, A. R., & Hellman, C. M. (2020). The potential protective effect of hope on students’ experience of perceived stress and burnout during medical school. The Permanente Journal, 24. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/19.240

Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031780

Einav, M., & Margalit, M. (2019). Sense of coherence, hope theory and early intervention: A longitudinal study. Journal for Educators, Teachers and Trainers, 10(2), 64–75. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/60055

Einav, M., & Margalit, M. (2022). The hope theory and specific learning disorders and/or attention deficit disorders (SLD/ADHD): Developmental perspectives. Current Opinion in Psychology, 101471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101471

Eryılmaz, A., & Kara, A. (2021). Inhibitors of Teachers’ Career Adaptability: Burnout and Loneliness in Work Life. International Journal of Educational Researchers, 12(3), 41–51, https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijers .

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149

Ferradás, M. D. M., Freire, C., García-Bértoa, A., Núñez, J. C., & Rodríguez, S. (2019). Teacher profiles of psychological capital and their relationship with burnout. Sustainability, 11(18), 5096. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185096

Fiorilli, C., Albanese, O., Gabola, P., & Pepe, A. (2017). Teachers’ emotional competence and social support: Assessing the mediating role of teacher burnout. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1119722

Fiorilli, C., Benevene, P., De Stasio, S., Buonomo, I., Romano, L., Pepe, A., & Addimando, L. (2019). Teachers’ burnout: The role of trait emotional intelligence and social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2743.

Fisherman, S. (2016). Professional identity and burnout among teachers. Shaanan. (hebrew). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02743

Fisk, G. M., & Neville, L. B. (2011). Effects of customer entitlement on service workers’ physical and psychological well-being: A study of waitstaff employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(4), 391. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023802

Fornaciari, A. (2019). A lonely profession? Finnish Teachers’ Professional Commitments. Schools, 16(2), 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1086/705645

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Friedman, I. A. (2003). Self-efficacy and burnout in teaching: The importance of interpersonal-relations efficacy. Social Psychology of Education, 6(3), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024723124467

Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2018). The Oxford handbook of hope. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199399314.001.0001

Garcia-Arroyo, J. A., Osca Segovia, A., & Peiró, J. M. (2019). Meta-analytical review of teacher burnout across 36 societies: The role of national learning assessments and gender egalitarianism. Psychology & Health, 34(6), 733–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1568013

George-Levi, S., & Laslo-Roth, R. (2021). Entitlement, hope, and life satisfaction among mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04832-6

Greenglass, E. R., Burke, R. J., & Konarski, R. (1998). Components of burnout, resources, and gender-related differences. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(12), 1088–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01669.x

Grubbs, J. B., & Exline, J. J. (2016). Trait entitlement: A cognitive-personality source of vulnerability to psychological distress. Psychological Bulletin, 142(11), 1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000063

Guan, B., & Jepsen, D. M. (2020). Burnout from emotion regulation at work: The moderating role of gratitude. Personality and Individual Differences, 156, 109703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109703

Gungor, A. (2019). Investigating the relationship between social support and school burnout in Turkish middle school students: The mediating role of hope. School Psychology International, 40(6), 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034319866492

Harandi, T. F., Taghinasab, M. M., & Nayeri, T. D. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(9), 5212. https://doi.org/10.19082/5212

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

Hosseini, S. F., Manochehri, A., Karimi, M., & Manochehri, S. (2023). The role of transformational leadership in employee burnout with an emphasis on the mediating variables of anxiety, job stress and loneliness at work (Case study: Primary education teachers in Paveh city). Governance and Development Journal, 3(1), 143–170. https://doi.org/10.22111/JIPAA.2023.394329.1118

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

Innstrand, S. T., Langballe, E. M., Falkum, E., & Aasland, O. G. (2011). Exploring within-and between-gender differences in burnout: 8 different occupational groups. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 84, 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0667-y

Jamaludin, I. I., & You, H. W. (2019). Burnout in relation to gender, teaching experience, and educational level among educators. Education Research International, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7349135

Jans-Beken, L., Jacobs, N., Janssens, M., Peeters, S., Reijnders, J., Lechner, L., & Lataster, J. (2020). Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 743–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1651888

Jiang, L., Tripp, T. M., & Hong, P. Y. (2017). College instruction is not so stress free after all: A qualitative and quantitative study of academic entitlement, uncivil behaviors, and instructor strain and burnout. Stress and Health, 33(5), 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2742

Jordan, P. J., Ramsay, S., & Westerlaken, K. M. (2017). A review of entitlement: Implications for workplace research. Organizational Psychology Review, 7(2), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386616647121

Kasalak, G., & Dağyar, M. (2021). Teacher burnout and demographic variables as predictors of teachers’ enthusiasm. Participatory Educational Research, 9(2), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.22.40.9.2

Kelly, M. E., Duff, H., Kelly, S., McHugh Power, J. E., Brennan, S., Lawlor, B. A., & Loughrey, D. G. (2017). The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2

Kim, S. K., Zhan, Y., Hu, X., & Yao, X. (2021). Effects of customer entitlement on employee emotion regulation, conceding service behavior, and burnout: The moderating role of customer sovereignty belief. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2020.1797680

Lackaye, T., & Margalit, M. (2006). Comparisons of achievement, effort and self-perceptions among students with learning disabilities and their peers from different achievement groups. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(5), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194060390050501

Lan, Y., Ma, Y., Dong, K., Gu, S., & Yang, X. (2019). Association of workplace loneliness, job burnout and conscientiousness in teachers of special education in Guangxi. China Occupational Medicine, 438–441. ID: wpr-881815

Lange, J., Redford, L., & Crusius, J. (2019). A status-seeking account of psychological entitlement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(7), 1113–1128. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/9tvm2

Li, H. (2021). Follow or not follow?: The relationship between psychological entitlement and compliance with preventive measures to the COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences, 174, 110678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110678

Li, M. H., Eschenauer, R., & Persaud, V. (2018). Between avoidance and problem solving: Resilience, self-efficacy, and social support seeking. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12187

Lyndon, M. P., Henning, M. A., Alyami, H., Krishna, S., Zeng, I., Yu, T. C., & Hill, A. G. (2017). Burnout, quality of life, motivation, and academic achievement among medical students: A person-oriented approach. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6, 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-017-0340-6

MacDonald, K. J., Willemsen, G., Boomsma, D. I., & Schermer, J. A. (2020). Predicting loneliness from where and what people do. Social Sciences, 9(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9040051

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101714

Madigan, D. J., Kim, L. E., Glandorf, H. L., & Kavanagh, O. (2023). Teacher burnout and physical health: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 119, 102173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102173

Marcionetti, J., & Castelli, L. (2023). The job and life satisfaction of teachers: A social cognitive model integrating teachers’ burnout, self-efficacy, dispositional optimism, and social support. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 23(2), 441–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09516-w

Maslach, C. (1998). A multidimensional theory of burnout. Theories of Organizational Stress, 68(85), 16.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

Mijakoski, D., Cheptea, D., Marca, S. C., Shoman, Y., Caglayan, C., Bugge, M. D., Gnesi, M., Godderis, L., Kiran, S., McElvenny, D. M., Mediouni, Z., Mesot, O., Minov, J., Nena, E., Otelea, M., Pranjic, N., Mehlum, I. S., Van der Molen, H. F., & Canu, I. G. (2022). Determinants of burnout among teachers: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5776. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/9/5776

Mund, M., Maes, M., Drewke, P. M., Gutzeit, A., Jaki, I., & Qualter, P. (2022). Would the real loneliness please stand up? the validity of loneliness scores and the reliability of single-item scores. Assessment, 30(4), 1226–1248. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221077227

Nadon, L., De Beer, L. T., & Morin, A. J. (2022). Should burnout be conceptualized as a mental disorder? Behavioral Sciences, 12(3), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12030082

Nguyen, T. D., & Springer, M. G. (2023). A conceptual framework of teacher turnover: A systematic review of the empirical international literature and insights from the employee turnover literature. Educational Review, 75(5), 993–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1940103

Ouyang, C., Zhu, Y., Ma, Z., & Qian, X. (2022). Why employees experience burnout: An explanation of illegitimate tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 8923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158923

Ozturk, Y. E. (2020). A theoretical review of burnout syndrome and perspectives on burnout models. Bussecon Review of Social Sciences, 2(4), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.36096/brss.v2i4.235

Park, E. Y., & Shin, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of special education teachers’ burnout. Sage Open, 10(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/215824402091829.

Pavlidou, K., Alevriadou, A., & Antoniou, A. S. (2022). Professional burnout in general and special education teachers: The role of interpersonal coping strategies. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1857931

Peplau, L. A. (1985). Loneliness research: Basic concepts and findings. In Social support: Theory, research and applications (pp. 269–286). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315803128-28

Pharris, A. B., Munoz, R. T., & Hellman, C. M. (2022). Hope and resilience as protective factors linked to lower burnout among child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 136, 106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106424

Piotrowski, J., & Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M. (2009). Kwestionariusz roszczeniowości (The entitlement questionnaire). Roczniki Psychologiczne, 12(2), 151–178.

Pleeging, E., Burger, M., & van Exel, J. (2021). The relations between hope and subjective well-being: A literature overview and empirical analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16, 1019–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09802-4

Portocarrero, F. F., Gonzalez, K., & Ekema-Agbaw, M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 164, 110101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110101

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03206553

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Răducu, C. M., & Stănculescu, E. (2022). Personality and socio-demographic variables in teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 14272. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18581-2

Rosenstreich, E., Feldman, D. B., Davidson, O. B., Maza, E., & Margalit, M. (2015). Hope, optimism and loneliness among first-year college students with learning disabilities: A brief longitudinal study. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(3), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1023001

Ruser, J. B., Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M. A., Gilbert, J. N., Gilbert, W., & Moore, S. D. (2020). Gratitude, coach–athlete relationships and burnout in collegiate student-athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 15(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2019-0021

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA loneliness scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching: A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching, 26(7–8), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1304_01

Statman, R. (1995). Women’s adjustment to civilian life after retiring from the army. University of Haifa.

Szkody, E., Stearns, M., Stanhope, L., & McKinney, C. (2021). Stress-buffering role of social support during COVID-19. Family Process, 60(3), 1002–1015. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12618

Turinas, E., Mosley, K. C., & McCarthy, C. J. (2023). Understanding the impact of receiving gratitude on teachers: Assessing the effect of risk-for-stress on perception of gratitude. Teaching and Teacher Education, 133, 104267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104267

Tvedt, M. S., Bru, E., Idsoe, T., & Niemiec, C. P. (2021). Intentions to quit, emotional support from teachers, and loneliness among peers: Developmental trajectories and longitudinal associations in upper secondary school. Educational Psychology, 41(8), 967–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1948505

Vo, D. T., & Allen, K. A. (2022). A systematic review of school-based positive psychology interventions to foster teacher wellbeing. Teachers and Teaching, 28(8), 964–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2022.2137138

Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

Wei, C., & Ye, J. H. (2022). The impacts of work-life balance on the emotional exhaustion and well-being of college teachers in China. Healthcare, 10(11), 2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112234

Wiggan, G., Smith, D., & Watson-Vandiver, M. J. (2021). The national teacher shortage, urban education and the cognitive sociology of labor. The Urban Review, 53, 43–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-020-00565-z

Xiang, Y., & Yuan, R. (2021). Why do people with high dispositional gratitude tend to experience high life satisfaction? A broaden-and-build theory perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 2485–2498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00310-z

Yang, H., Liang, C., Liang, Y., Yang, Y., Chi, P., Zeng, X., & Wu, Q. (2023). Association of gratitude with individual and organizational outcomes among volunteers: An Application of Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. SAGE Open, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231210372.

Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M. A. (2022). Student academic engagement and burnout amidst COVID-19: The role of purpose orientations and disposition towards gratitude in life. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15210251221100415. https://doi.org/10.1177/15210251221100415

Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M. A., Piotrowski, J. P., & Maltby, J. (2017). Agentic and communal narcissism and satisfaction with life: The mediating role of psychological entitlement and self-esteem. International Journal of Psychology, 52(5), 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12245

Zhang, Y., Tsang, K. K., Wang, L., & Liu, D. (2022). Emotional labor mediates the relationship between clan culture and teacher burnout: An examination on gender difference. Sustainability, 14(4), 2260. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042260

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Zimmerman, S. (2011). Gratitude, wellbeing and personal growth among mothers to children with and without disabilities. Bar Ilan University.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to express our gratitude to Hadas Shwartz, the director of the Psycho-education center of Lod for her feedback and support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Peres Academic Center. We don’t have any funding for this manuscript nor any conflict of interest. We confirm that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by any other journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Michal Einav, Dan Confino, Noa Geva, and Malka Mergalit. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Michal Einav, Dan Confino, Noa Geva and Malka Mergalit and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Einav, M., Confino, D., Geva, N. et al. Teachers’ Burnout – The Role of Social Support, Gratitude, Hope, Entitlement and Loneliness. Int J Appl Posit Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00154-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00154-5