Abstract

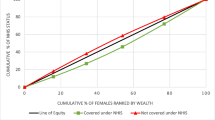

This paper presents an assessment of publicly funded health insurance (PFHI) schemes as a measure of social health protection (SHP) in the country. The study uses secondary data from the nationally representative large-scale survey data on household social consumption related to health from three National Sample Survey (NSS) rounds—60 (2004), 71 (2014), and 75 (2017–18). The analysis of PFHI schemes is done on three metrics—population coverage, service coverage, and financial coverage. The analytical framework of the paper is based on the conceptual framework of the universal health coverage (UHC) cube of the World Health Organization (WHO) (“UHC cube” exhibits three dimensions of coverage: i.e., breadth of the cube—the population [who is covered?], depth of the cube—services [which are covered], and height of the cube—cost sharing [what proportion of costs are covered?]). To achieve the long-standing goal of UHC, improvements need to be made across each dimension in order to help fill the cube (Van Leberghe 2008). From the available data on population coverage, the national estimates of PFHI coverage in the country show a limited proportion of rural and urban population being covered in 2017–18. PFHI schemes provide coverage for only selective secondary and tertiary care, and not comprehensive care as per the design of the schemes. Outpatient care including diagnostics, and medicines are not covered under these schemes. High out-of-pocket expenditures (OOPEs) despite PFHI schemes are observed with disproportionately higher expenditures in private hospitals. This raises serious concerns with the direction of public policy that prioritises the national PFHI, PMJAY (Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana) to solve the social health protection (SHP) problem for the workforce of the country. The existing social health insurance ESIS (Employees’ State Insurance Scheme) which only covers a small section of the labour force is, however, relatively better in terms of its benefits cover (second arm of the UHC cube) and financial protection (third arm of the UHC cube) as seen in the OOPE per hospitalisation case as compared to PFHI schemes and might offer useful lessons for expanding social security to the country’s workforce.

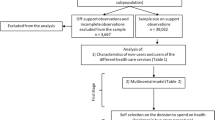

Source: Author’s estimates using unit-level NSS 75th round data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines UHC as “all people having access to the health care they need without suffering financial hardship”.

Shahra, Razavi (2022) Making the Right to Social Security a Reality for All Workers The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65(2)

ESIS is the statutory and contributory social health insurance for factory workers employed in factories with more than 10 workers and earning up to a ceiling of ₹21,000 per month and their families.

It also includes workers in shops, hotels, cinema halls, restaurants, road motor transport, newspapers, warehouses, ports, airports, NBFCs, insurance business establishments. Workers in educational institutes, private medical colleges are also included in 27 states.

ESIC Annual Report 2019–20 (Ministry of Labour and Employment, 2020)

See World Health Report (2008).

RSBY was launched by the Union government by the Ministry of Labour and Employment in 2008 to provide respite from hospitalisation expenses (mainly secondary care) up to ₹30,000 annual coverage for BPL households. It aimed to cover 70 million families or 350 million persons by the end of 2017. In 2011, it was expanded to cover unorganised sector workers including construction labourers, beedi workers sanitation workers, street vendors, domestic workers, rag-pickers, taxi and rickshaw drivers, and mine workers.

(https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=108156).

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc), Last accessed on 31.12.2020 at 3:57 pm.

See World Health Report (2008).

The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served (Hart 1971 p 412). It is further argued that the law operates more completely with greater exposure to market forces in medical care and vice versa.

Purchaser–provider split translates into a clear separation between financing of services provided and facilities where these services would be provided. Purchasing is the situation when rather than providing the services directly by themselves, a health actor asks another party to provide the services in exchange for a payment (Perrot 2006).

Hooda (2020) cites the government claim of official coverage of PFHIschemes till 2017–18 for 27 states of the country as 10.9 crore families, while NSS 75th round coverage is 3.46 crore families.

References

Alkire, S., and S. Seth. 2013a. Identifying BPL households: A comparison of methods. Economic and Political Weekly 48 (2): 49–57.

Alkire, S., and S. Seth. 2013b. Selecting a targeting method to identify BPL households in India. Social Indicators Research 112: 417–446.

Barnagarwala, T. 2022. The pandemic’s hidden cost: Much-hyped health insurance scheme failed to cover hospital bills, Scroll.in: https://scroll.in/article/1020201/the-pandemics-hidden-cost-much-hyped-health-insurance-scheme-failed-to-cover-hospital-bills. Last accessed on 24 Mar 2022, 1:20 pm.

Baronetti, S. 2020. Social protection spotlight—Towards universal health coverage: Social health protection principles (2020), ILO Brief.

Bergkvist, S., A. Wagstaff, A. Katyal, P. Singh, A. Samarth, and M. Rao. 2014. What a difference a state makes: Health reform in Andhra Pradesh. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6883.

Choudhury, M., and P. Datta. 2019. Private hospitals in health insurance network in India: a reflection for implementation of Ayushman Bharat (No. id: 13009).

Choudhury, M., S. Tripathi, and J.D. Dubey. 2019. Experiences with government sponsored health insurance schemes in Indian states: a fiscal perspective (No. 19/283).

Dreze, J. 2018. Ayushman Bharat trivialises India’s quest for Universal Health Care, The Wire: https://thewire.in/health/ayushman-bharat-trivialises-indias-quest-for-universal-health-care

Dreze, J., and R. Khera. 2015. Understanding leakages in the public distribution system. Economic and Political Weekly 39–42.

Dror, D.M., and S. Vellakkal. 2012. Is RSBY India’s platform to implementing universal hospital insurance? The Indian Journal of Medical Research 135 (1): 56–63. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5916.93425.

Duggal, R. 2015. Saving the employees' state insurance scheme. Economic and Political Weekly 17–20.

Duggal, R., and S. Hooda. 2021. COVID-19, health insurance and access to healthcare. Economic and Political Weekly 56 (31): 10–12.

Extending Social Health Protection: Accelerating progress towards universal health coverage in Asia and the Pacific 2021. Bangkok: International Labour Organisation (ILO).

La Forgia, G., and S. Nagpal. 2012. Government-sponsored health insurance in India: Are you covered? World Bank Publications.

Garg, S. 2019. Study of strategic purchasing as a policy option for public health system in India. Doctoral dissertation. Mumbai: Tata Institute of Social Sciences. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/259965

Garg, S., S. Chowdhury, and T. Sundararaman. 2019. Utilisation and financial protection for hospital care under publicly funded health insurance in three states in Southern India. BMC Health Services Research 19 (1): 1–11.

Garg, S., K.K. Bebarta, and N. Tripathi. 2020. Performance of India’s national publicly funded health insurance scheme, Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogaya Yojana (PMJAY), in improving access and financial protection for hospital care: Findings from household surveys in Chhattisgarh state. BMC Public Health 20 (1): 1–10.

Ghosh, S. 2014. Publicly-financed health insurance for the poor: Understanding RSBY in Maharashtra. Economic and political weekly 93–99.

Ghosh, S. 2018. Publicly financed health insurance schemes. Economic and Political Weekly 53 (23): 16–18.

Hart, J.T. 1971. The inverse care law. Lancet i: 405–12.

Himanshu, and A. Sen. 2011. Why not a universal food security legislation? Economic and Political Weekly 38–47

Hooda, S.K. 2020. Penetration and coverage of government-funded health insurance schemes in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 8 (4): 1017–1033.

https://accountabilityindia.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Ayushman-Bharat-2021-22.pdf

https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/SS_Code_Gazette.pdf

https://www.esic.nic.in/attachments/publicationfile/5feb31f78398e8aa9fcec533089df23a.pdf

https://www.irdai.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/NormalData_Layout.aspx?page=PageNo4&mid=2

https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=8733

https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)

ILO. 2008. Social Health Protection, An ILO Strategy towards universal access to healthcare, Social Security Department, International Labour Office, ILO Geneva.

ILO. 2020. Promoting employment and decent work in a changing landscape. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (articles 19, 22 and 35 of the Constitution) Report III (Part B) ILC 109th Session.

Gillis, M., C. Shoup, and G.P. Sicat. 2001. World Development Report 2000/2001—Attacking poverty. World Bank.

Karan, A., W. Yip, and A. Mahal. 2017. Extending health insurance to the poor in India: An impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Social Science & Medicine 181: 83.

Khera, R. 2011. Revival of the public distribution system: Evidence and explanations. Economic and Political Weekly xlvi (44): 45.

Ministry of Labour and Employment. 2020. ESIC Annual Report 2019–20, ESIC.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. 2019. Report of the technical group on population projections. Population Projections for India and states 2011–2036.

Mukhopadhyay, I., Bose, Montu. 2020. Private Healthcare Industry in India: 4 Common Myths Debunked, Business Standard: https://www.businesstoday.in/opinion/columns/private-healthcare-industry-in-india-five-common-myths-debunked-public-and-private-sector/story/409872.html

Nandi, S. 2019. Equity, access and utilisation in the state-funded universal insurance scheme (RSBY/MSBY) in Chhattisgarh state, India: What are the implications for Universal Health Coverage?, Doctoral Dissertation, University of the Western Cape.

Nandi, S., and H. Schneider. 2020. Using an equity-based framework for evaluating publicly funded health insurance programmes as an instrument of UHC in Chhattisgarh State, India. Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1): 1–14.

Patel, J.A., F.B.H. Nielsen, A.A. Badiani, S. Assi, V.A. Unadkat, B. Patel, and H. Wardle. 2020. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: The forgotten vulnerable. Public Health 183: 110.

Perrot, J. 2006. Different approaches to contracting in health systems. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84(11).

Rao, K.S. 2016. Do we care?: India’s health system. Oxford University Press.

Ranjan, A., P. Dixit, I. Mukhopadhyay, and S. Thiagarajan. 2018. Effectiveness of government strategies for financial protection against costs of hospitalisation Care in India. BMC Public Health 18 (1): 1–12.

Ravi, Shamika, Ahluwalia, Rahul and Bergkvist, Sofi. 2016. Health and Morbidity in India (2004–2014). Brookings India Research Paper No. 092016.

Razavi, S. 2020. Social Protection pays off, Project Syndicate: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/covid19-vindicates-social-protection-systems-by-shahra-razavi-2020-03?barrier=accesspaylog

Reddy, S., and I. Mary. 2013. Aarogyasri scheme in Andhra Pradesh, India: Some critical reflections. Social Change 43 (2): 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049085713492275.

Saxena. 2015. The poor don’t count so why count the poor? The Wire. https://thewire.in/economy/not-counting-the-poor

Selvaraj, S., and A.K. Karan. 2012. Why publicly-financed health insurance schemes are ineffective in providing financial risk protection. Economic and Political Weekly 60-68

Selvaraj, S., A. Karan, C. Chaudhuri, S. Hussain, M. Rajna, and V. Raaj. 2022. Accessing medical benefits under ESI Scheme: A demand-side perspective.

Selvaraj, S., A.K. Karan, W. Mao, H. Hasan, I. Bharali, P. Kumar, O. Ogbuoji, and C. Chaudhuri. 2021. Did the poor gain from India’s health policy interventions? Evidence from benefit-incidence analysis, 2004–2018. International Journal for Equity in Health 20 (1): 1–15.

Sengupta, A. 2013. Universal health coverage: Beyond rhetoric. Occasional Paper 20: 25.

Shukla et al. 2011. Aarogyasri Healthcare Model: Advantage Private Sector, Economic and Political Weekly XLVI (49).

Shukla, R. 2020. As the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana Evolves, Some Challenges Remain Rooted. Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research. Available at: http://accountabilityindia.in/blog/as-the-pradhan-mantri-jan-arogya-yojana-evolves-some-challenges-remain-rooted/.

Srinivas, A. 2019. The targeting challenge in India’s welfare programs. Mint. https://www.livemint.com/politics/policy/ the-targeting-challenge-in-india-s-welfare-programs-1557294982507.html.

Surabhi. 2023. Centre looks to expand coverage, revamp working of ESIC, EPFO The Hindu BusinessLine. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/policy/centre-looks-to-expand-coverage-revamp-working-of-esic-epfo/article65805352.ece. Last accessed on 24 May 2023 at 12:50 pm.

Suryahadi, A., Al Izzati, R., and Suryadarma, D. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 outbreak on poverty: An estimation for Indonesia. Jakarta: The SMERU Research Institute.

Trivedi, M. 2021. Can India’s Flagship Public Health Insurance Scheme Do What It Promises? The India Forum. https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/can-india-s-flagship-public-health-insurance-scheme-do-what-it-promises.

Van Leberghe, W. 2008. The World Health Report 2008: Primary health care: Now more than ever, World Health Organisation.

Whitehead, Margaret, David Taylor-Robinson, and Ben Barr. 2021. Poverty, health, and Covid-19. bmj 372.

WHO. 2004. Investing in Health for Economic Development. https://www.who.int/ macrohealth/action/sintesis15novingles.pdf.

WHO. 2022. Analysing the effectiveness of targeting under AB PM-JAY in India.

Shahra, Razavi. 2022. Making the Right to Social Security a Reality for All Workers. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65(2): 269-294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00378-6

Khetrapal, S. 2016. Public-Private Partnerships in the Health Sector The Case of a National Health Insurance Scheme in India (Doctoral dissertation, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine).

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Dipa Sinha and the anonymous referee for their comments. I would also like to thank ISLE for giving a platform to present my work at the ISLE 62nd Labour Economics Conference, held at IIT Roorkee (11-13 April 2022). The suggestions and feedback received at the Conference helped to solidify my research findings.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, A. Social Health Protection and Publicly Funded Health Insurance Schemes in India: The Right Way Forward?. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 66, 513–534 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-023-00445-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-023-00445-6