Abstract

This work aims to evaluate the impact of small amounts of hydrogen on the hydrogen-assisted cracking (HAC) of 17-4 martensitic stainless steel (SS) prepared by additive manufacturing (AM). To elucidate the effect of processing on the hydrogen–material interactions, the obtained results were compared with a conventionally manufactured (CM) counterpart. It was found that the hydrogen uptake of AM 17-4 SS is higher compared to CM; however, its resistance to HAC is improved. These differences are attributed to the presence of stronger hydrogen trapping sites, retained austenite and the absence of Nb-rich precipitates in the AM 17-4 SS. The effect of processing on the microstructure and the susceptibility to hydrogen-induced damage and hydrogen embrittlement is discussed in detail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The combination of high strength and good corrosion resistance makes 17-4 martensitic stainless steel (SS) a versatile material which can be used in various applications, such as aerospace, chemical processing equipment or gas industry [1]. However, severe problems can arise when SS encounters hydrogen [2, 3]. The presence of hydrogen atoms within the material might result in significant deterioration of mechanical properties, leading to an unexpected failure. This phenomenon is known as hydrogen embrittlement (HE) [4, 5]. In general, the susceptibility of high-strength martensitic steels to HE correlates with the strength of the steel: the higher the strength, the lower is the hydrogen uptake necessary for promoting sensitivity to HE [1]. For example, hydrogen concentration of 0.5–1 wt% ppm promotes internal hydrogen embrittlement in steel with strength of ~1400 MPa [6]. Therefore, it is very important to recognize the possible mechanism of hydrogen-induced degradation of the material to predict safe service conditions.

Hydrogen trapping in microstructural defects, so-called hydrogen traps, strongly affects the susceptibility of materials to HE [7, 8]. If the traps are relatively strong, they are considered to be irreversible and act as hydrogen sinks. Conversely, weak (reversible) hydrogen traps can supply hydrogen to critical cracking locations, acting as hydrogen source [8]. The activation energy (i.e., the energy required for the hydrogen atom to be released from the trap) of ~60 kJ/mol is regarded as an upper limit for the reversible traps [9].

Nowadays, the production of 17-4 SS can be made by various additive manufacturing (AM) technologies [10,11,12]. Moreover, due to its good weldability, 17-4 SS is one of the two precipitation-hardened steels which are practically exclusively in use in AM today, aside from 15-5 SS [10]. The use of AM technologies provides optimization of shape and volume of the designed SS parts, thus decreasing their weight. In addition, the need for many post-processing steps and expensive tooling is reduced, reducing the cost production [13]. The mechanical properties of AM 17-4 SS are comparable to those of wrought counterparts, or even better than them [13]. AM 17-4 SS can be used in various applications, for example in the fabrication of complicated injection molds with conformal cooling channels [14, 15] or NASA wind tunnel balances [16]. Moreover, AM processing enables enhancing the mechanical properties of the as-printed part in a specific direction. As a result, AM 17-4 SS can be used in various aeronautical applications, where the parts are predominantly loaded in one direction, such as wing spars, landing gear components and engine mounts [17].

The complex thermal history and high cooling rates of the AM processing lead to formation of a unique microstructure of the as-printed parts, which significantly differs from that of conventionally manufactured (CM) parts [13]. For instance, the amount of metastable retained γ-austenite within the martensitic structure of AM 17-4 SS can be <1-3% volume fraction up to 97% [11], and the presence of other phases such as δ-ferrite [18] and Nb-rich carbides [19] has been reported. Precipitation of the Cu phase is achieved by post-processing heat treatments (HT) of the AM parts [19, 20]. The HT can also decrease the amount of retained austenite [21]. It should be noted that the structure of as-printed AM 17-4 SS presents a large variability depending on the process parameters [10].

The effect of hydrogen on 17-4 SS has been widely studied, and it is found to be strongly dependent on the characteristics of the trapping sites within the steel. The proposed hydrogen traps are dislocations [22], grain boundaries [23], precipitate/matrix interfaces [23,24,25,26,27], retained and/or reverted austenite [22, 27], or δ-ferrite [28]. The strength of the trap has a crucial effect on the susceptibility to HE, since hydrogen trapped in weak trapping sites can be released under mechanical loading. Afterwards it diffuses to martensite lath boundaries, promoting quasi-cleavage fracture [25]. Moreover, it was shown that semi-coherent precipitates in over-aged specimens behave as stronger hydrogen traps, compared to coherent precipitates in peak-aged specimens. Therefore, the overaged specimens usually present higher resistance to HE [25, 28]. As for the AM-produced 17-4 SS, the few published studies report higher susceptibility of the AM part to HE [29], stress corrosion cracking [30] and environmentally assisted cracking [31], compared to CM. The hydrogen uptake of the AM 17-4 SS was found to be higher, indicating higher hydrogen diffusivity rate [29, 31]. However, it should be noted that the studied AM 17-4 SS undergo post-processing HT, which might alter their microstructure. Moreover, there is a lack of information regarding hydrogen trapping sites within the AM 17-4 SS.

The present study investigates the interactions of small amounts of hydrogen with the as-printed 17-4 SS produced by laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) method. For better understanding of the effect of AM on the initial microstructure and hydrogen trapping characteristics, we will compare 17-4 SS produced by LPBF with CM 17-4 SS. The hydrogen was introduced into the material via cathodic hydrogen charging (CHC), and its interactions with various trapping sites were studied through thermal desorption spectroscopy (TDS). The aim of this work is to clarify the mechanism of environmental degradation of AM-produced SS in a hydrogen environment.

2 Experimental

The 17-4 SS was prepared by a direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) technique, using a ProX Direct Metal Printing (DMP) 300 machine (Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel). The tensile specimens were manufactured in a protective nitrogen atmosphere, using a beam with a maximum power of 500 W. The process entailed the use of metal powder with an average particle range of ~ 35 µm; layer thickness, scanning speed and hatch spacing were set to 40 µm, 800 mm/s, and 40 µm, respectively. For the subsequent building layers the scanning direction was rotated by 90°. The dimensions of the produced tensile specimens were designed according to ASTM D638–14 standard [32]. The tensile direction was perpendicular to the building direction of DMLS, as shown in Figure 1, and the XZ-plane was studied. The microstructure and hydrogen interactions with the AM 17-4 SS were compared to a conventionally manufactured counterpart of 17-4 SS (ASTM A564/A564M–13 [33]). The CM specimens were subjected to a solution HT at 1900° F for 1.5 h, followed by an air quench. Then, the samples were aged at 1150° F for 4 h to an overaged condition (H1150). The chemical composition of AM and CM 17-4 SS specimens, as reported by the manufacturer, is presented in Table 1.

The electrochemical charging of 17-4 SS was performed in a 1 N H2SO4 water solution and 0.25 g/L of sodium arsenide (NaAsO2) as a surface recombination inhibitor. The current density was set to 50 mA/cm2 and the samples were charged at RT for 96 hours. After charging, the samples were stored in liquid nitrogen to avoid hydrogen outgassing.

The microstructure of the studied alloys before and after hydrogenation was investigated by means of optic microscopy (OM), using Carl Zeiss Axio Observer A1m optical microscope. Further study of the microstructure was performed by JEOL JSM-IT100 scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS), and JEOL JEM-2100 F analytical transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with Gatan 894 US1000 camera and a JED-2300 T EDS detector. Samples for TEM studies were prepared by focused ion beam (FIB), using a Helios NanoLab 460F1 DB instrument. Phase identification of the studied alloys, as well as hydrogen related phase transformation, were carried out using a Rigaku D/MAX-2000 X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with a Cu Kα radiation and scanning velocity of 0.02°/s.

Hydrogen interactions with the studied materials was investigated by means of TDS, a technique which entails the hydrogenated specimen being non-isothermally heated at a known constant rate, while the desorption rate of hydrogen atoms is measured. In this work, TDS measurements were performed on hydrogenated samples cleaned with ethanol. The specimen was placed in a specimen holder, and the system sealed and pumped down to 10-7 mbar. The specimen was then heated from RT to 500 °C at three constant heating rates of 2 °C/min, 4 °C/min and 6 °C/min. During the heating phase, the quadrupole mass spectrometer (QMS) detected hydrogen desorption and evaluated the total quantity of atoms desorbed within the temperature range of the experiment. The working procedure, as described elsewhere [9, 34, 35], allows the identification of different types of traps coexisting in the specimen, as well as their activation energy and trap density.

3 Results

3.1 Microstructure and phase identification

The prevalent phase of CM and AM 17-4 SS is α'-martensite with a bcc crystal structure, as identified by XRD spectra in Figure 2. Additional peaks in the spectrum of AM 17-4 SS are attributed to γ-austenite with an fcc crystal structure. Since the AM specimen did not undergo any heat treatment, it is reasonable to suggest that these peaks originate from the retained, rather than reverted austenite. As described in Sect. 2, the AM specimens were processed in a protective nitrogen atmosphere. Using nitrogen rather than argon during the processing results in a higher nitrogen content in the as-printed sample [36]. Since nitrogen is known to be an austenite stabilizer [1], its presence in a solid solution might influence the amount of retained austenite in the AM specimens. The retained austenite dissociates during the solution heat treatment prior to aging [37]; thus, it is not observed in the CM specimen. Nevertheless, the amount of the austenite phase in the AM 17-4 SS is relatively low and was not visually identified by optical and electron microscopy.

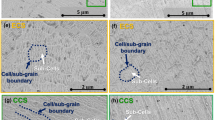

The microstructure of the CM specimen consists of former austenitic grain boundaries and martensite lath packs, as shown in Figure 3(a, b). The XZ-plane of the AM 17-4 SS presents elongated grains separated by melt pool boundaries, Figure 3(c). These grains are aligned parallel to the building direction since they grow epitaxially along the heat dissipation path toward the substrate [38]. Higher magnification SEM image in Figure 3(d) reveals fine striations within the grains. These striations are observed in columnar grains of AM 17-4 SS and are oriented toward the center of the melt pool, parallel to the <100> directions in the bcc crystal structure [21].

Detailed TEM study confirmed the presence of α′-martensite (SG: Im-3m, a = 0.287 nm) laths in both AM and CM 17-4 SS, Figure 4. In addition, multiple amorphous inclusions were observed in the AM specimen, Figure 5. The inclusions have a spherical shape with size of a few tens of nm, and according to TEM/EDS, Table 2, these are Si oxides. Oxide inclusions are commonly observed in AM 17-4 SS, and are believed to originate from the powder particles, which undergo melting and some limited further oxidation during the AM processing [39].

In the CM specimen, some polygonal-shaped precipitates were observed in the size of hundreds of nm, and their composition is presented in Table 3. Figure 6 presents a complex Nb-rich nitride phase (NbCrN) with a tetragonal crystal structure (SG: P4/nmm, a = 0.304 nm, c = 0.739 nm), also known as Z-phase. This phase was observed in austenitic [40], duplex [41, 42] and martensitic [42] SS after prolonged aging. A second type of precipitates, shown in Figure 7, was identified as Nb carbonitrides with an fcc crystal structure (SG: Fm-3m, a = 0.448 nm). This phase was also observed in conventionally produced 17-4 SS after HT [43, 44]. The absence of the nitride phases in AM 17-4 SS can be explained by the absence of subsequent heat treatment. As previously mentioned, the nitrogen most likely resides in a solid solution with γ-austenite. High cooling rates of DMLS processing do not alloy diffusion-controlled transformation into nitride phases as in the CM specimen. It should be noted that no carbide phases and Cu-rich precipitates were found in the AM and CM 17-4 SS, respectively.

3.2 The effect of hydrogenation on 17–4 SS

Hydrogenation of 17-4 PH SS resulted in cracking of the specimen’s surface, as shown in Figure 8. The cracking of CM specimen is more severe than that of the AM, implying better resistance to HAC of the AM specimen. Based on the previous microstructure observations, this phenomenon is attributed to the initially higher amount of the retained austenite and the absence of brittle nitride phases. The ductile austenite phase might blunt the crack tip and serve as an effective hydrogen trap due to the higher hydrogen solubility within [22, 45]. In addition, the presence of austenite in the matrix decreases the dislocation density and internal stress in the matrix, thus improving the material resistance to HAC [46]. Fine carbide/nitride phases might serve as a weak hydrogen trapping site, which can release diffusible hydrogen into the lattice and promote HE [47]. In addition, Cr-rich carbides might result in local Cr depletion of the nearby regions. Cr depletion of the GB was shown to increase susceptibility to HE [48].

3.3 TDS analysis of CHC 17–4 SS

The TDS spectra of CHC specimens of 17-4 SS, shown in Figure 9, reveal significant differences in hydrogen desorption characteristics of AM and CM 17-4 SS. The TDS spectra of the AM 17-4 SS, Figure 9(a), presents two desorption peaks, implying the presence of two main hydrogen traps. Their estimated activation energies are summarized in Table 4. Both values of the EaT are lower than 60 kJ/mol and thus represent a reversible trap. These traps can be either elastic stress field around dislocation or second-phase particles (~ 0–20 kJ/mol), or a dislocation core (~ 20–35 kJ/mol) [49,50,51,52,53]. It should be noted that, due to the high cooling rates during the DMLS processing and the absence of heat treatment, AM 17-4 SS is expected to present a higher density of dislocations. An additional possible trap with similar activation energy is attributed to the release of diffusible hydrogen trapped at γ/ε interfaces (~ 22 kJ/mol [54]).

CM 17-4 SS presents only one main hydrogen trapping site, with activation energy of 16±2 kJ/mol. This trap site can be attributed to martensite lath boundaries (~17 kJ/mol [55]), fine carbide precipitations (~ 17–21 kJ/mol [47]) or dislocations. In addition, the TDS spectra of CM 17-4 SS, Figure 9(b), is characterized by multiple straight narrow desorption peaks with relatively high intensity. This kind of peak was observed in the TDS spectra of other structural materials, e.g., magnesium alloy [56], and is related to the release of H2 molecules from the trapping sites. Based on the microstructural observations, we suggest that these peaks originate from H2 molecules released from the carbides/matrix interfaces in CM 17-4 SS.

The hydrogen uptake of CHC high-strength steels is usually in the range of several to tenths of wt% ppm [3, 57, 58]. The total amount of desorbed hydrogen, as estimated from integration of the TDS spectra, was estimated to be ~5 and ~0.5 wt% ppm for AM and CM 17-4 SS, respectively. The hydrogen uptake of the AM 17-4 SS is significantly higher, and this phenomenon is attributed to the higher content of austenite, as shown in Figure 2. The solubility of hydrogen in the martensite phase is lower by one or two orders of magnitude than that in the austenite [59, 60]. In addition, due to the DMLS processing, the AM specimen usually presents a higher dislocation density and a higher grain boundary density, compared to the CM specimen [29]. These microstructural features can serve as a short path for hydrogen diffusion inside the bulk, and their higher density in the AM 17-4 SS might increase hydrogen uptake during CHC.

4 Discussion

The environmental degradation of the studied materials is manifested by the hydrogen assisted cracking phenomenon. The presence of cracks on the surface of specimens with a very low hydrogen content implies high susceptibility of 17-4 SS to HE. Generally, all hydrogen induced degradation mechanisms in metallic systems must involve the transportation of hydrogen atoms to regions where interactions with metal will cause embrittlement [4, 5]. The availability of absorbed hydrogen to such regions depends on: (a) the rate of hydrogen transport inside the bulk material, and (b) the population and characteristics of hydrogen traps (microstructural defects) [6, 61]. Therefore, the initial microstructure of the material prior to exposure to hydrogen is of prime importance in determining the possible mechanism of environmental degradation. This, in turn, is controlled by the thermo-mechanical history of the material, particularly the process parameters of the AM production.

The microstructure of AM 17-4 SS presented some amount of retained austenite, whereas the microstructure of the CM counterpart was fully martensitic. Consequently, the presence of austenite in AM 17-4 SS is attributed to the AM processing. Austenite can be found in as-built AM 17-4 SS, due to the following reasons: (1) refined microstructure, manifested by smaller grain size and inter-dendritic spacing, (2) relatively high dislocation density due to the high cooling rates, (3) strain at high-angle GB which suppresses the γ → martensite transformation, (4) supersaturation of the austenite phase with phase stabilizing elements, and (5) powder manufacturing environment (argon on nitrogen gas) [19]. The studied specimens of AM 17-4 SS were manufactured in a protective nitrogen atmosphere, resulting in higher amounts of retained austenite. Additional difference in the microstructure is the presence of second phase particles: amorphous Si oxide inclusion, and Nb-rich nitrides and carbonitrides in AM and CM 17-4 SS, respectively. These particles can serve as hydrogen traps and either improve or deteriorate the resistance of the material to HE, depending on the strength of the trap.

It is clearly seen in Figure 8, that HAC of CM 17-4 SS is more severe than that of the AM specimen. This observation is even more interesting, considering the fact that the amount of desorbed hydrogen in the CM 17-4 SS was one order of magnitude lower than that of the AM specimen. The differences in the initial hydrogen uptake of the specimens are attributed to the different initial microstructure of the specimens prior to the hydrogen charging. Laser-based AM processing results in refined microstructure, manifested by increased density of dislocations and grain boundaries (GB). The increased dislocation density leads to a higher state of internal stress on the surface of pre-deformed specimens, which enhances the chemisorption of hydrogen and facilitates its entry into the material [62]. Moreover, the amount of absorbed hydrogen was shown to increase with the increasing deformation degree (i.e., increased dislocation density) [63]. GBs also serve as short-circuit paths for hydrogen diffusion, and their presence facilitates hydrogen entry to the material [64]. An additional parameter that might affect hydrogen ingress and diffusion in AM 17-4 SS is the presence of retained austenite. Since the diffusion coefficient of hydrogen in close-packed γ-austenite [65] is lower than in bcc martensite [66], the hydrogen outgassing from the charged specimen at room temperature is less pronounced for the CM 17-4 SS. Although the hydrogenated specimens were stored in liquid nitrogen to avoid hydrogen outgassing, some hydrogen could escape during the transfer of the specimens from the charging position to the liquid nitrogen, and then from the liquid nitrogen to the TDS facility. Therefore, the presence of retained austenite also contributes to the initially higher hydrogen uptake in AM 17-4 SS.

Retained austenite might also be one of the reasons for improved resistance of AM 17-4 SS to HAC. Martensite is a brittle phase, which undergoes cracking at relatively low stresses. Conversely, γ-austenite is a ductile phase which improves the resistance of the material to HE by blunting the crack tip and deflecting the crack growth path [67]. Moreover, due to the low hydrogen diffusion coefficient, γ-austenite might serve as a potential hydrogen trapping site and restrict HAC [51, 68], whereas martensite acts as a short-circuit path for hydrogen atoms to regions of high stress, promoting HA [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. In addition, the presence of austenite in martensitic SS decreases susceptibility to HE by trapping the hydrogen atoms and preventing their accumulation in martensite lath boundaries [71]. Consequently, the presence of retained γ-austenite within the martensite matrix of AM 17-4 SS improves the resistance of the material to hydrogen-induced damage.

HAC of AM 17-4 SS can also be restricted due to the presence of stronger trapping sites, as compared to the CM counterpart. It was shown that the susceptibility of SS to hydrogen induced damage strongly depends on the strength of the hydrogen trapping sites [22,23,24,25,26, 51, 65]. Strong hydrogen traps prevent diffusion of hydrogen into cracking zones, whereas weak hydrogen traps can release the trapped hydrogen at relatively low temperatures and/or under mechanical loading, serving as detrimental hydrogen sources within the material [8]. According to the TDS measurements, both AM and CM 17-4 SS present only reversible trapping sites. However, the activation energy of the trapping site in CM 17-4 SS is ~35% lower than in the AM counterpart. Based on the literature, this trap with activation energy of ~16 kJ/mol is attributed to martensite lath boundaries [55]. In addition, the TDS spectra of the CM specimen presented multiple narrow peaks, which were ascribed to the release of trapped hydrogen molecules. These types of peaks were not observed in the AM specimen. Based on the microstructural observations, it can be suggested that the hydrogen molecules were trapped in the interfaces between the matrix and nano-particles of NbCrN and Nb carbonitrides in CM 17-4 SS. Second phases in 17-4 SS, especially carbides, generally represent strong hydrogen trapping sites [3]. However, fine carbide precipitates and/or coherent interfaces in tempered materials possess relatively low values of activation energy [47, 55]. A recent study showed that hydrogen trapped in coherent Cu-precipitates can easily escape from the trapping site under loading and reduce the resistance to HE [25]. Moreover, when Cu-precipitates exceed a particular critical size (~30 nm) in specimens aged at high temperature, they do not act as active significant hydrogen trapping sites [26]. In addition, it was found that coarsening of η-Ni3Ti particles during long-term aging decreased their hydrogen trapping capacity [22]. Therefore, it can be suggested that in over-aged CM 17-4 SS the precipitates might serve as weak hydrogen traps. Conversely, in AM 17-4 SS, hydrogen is trapped mainly in dislocations. Since no subsequent heat treatment was performed for the AM 17-4 SS, no precipitates were found in its microstructure, except for oxide nanoinclusions. These inclusions are known to deteriorate the mechanical properties of the steel [39], but according to our study their effect on the susceptibility to HE seems insignificant.

Hydrogen-induced cracking of martensitic SS is generally attributed to the accumulation of hydrogen atoms at martensitic lath boundaries along with dislocation pile-ups against GB. When hydrogen content exceeds a critical value, it reduces the effective work for fracture. As a result, the HE will likely occur through the hydrogen enhanced decohesion (HEDE) mechanism [57]. The basic principle of this mechanism is that the solute hydrogen decreases the cohesive strength of the cleavage planes. This results in rupture of the crystal at lower stresses [4, 72]. In martensitic SS crack is expected to initiate along the lath boundaries, and then to propagate to an intergranular fracture [28]. The cracking will take place on the lath interfaces rather than on primary austenite GB, since the intrinsic fracture strength of lath boundary is lower than of prior austenite GB, even if the concentration of trapped hydrogen is equal [73]. Trapping of hydrogen in dislocations in AM 17-4 SS decreases the hydrogen content at the martensite lath boundaries, thus improving the resistance of the material to HE, compared to CM. Yet, under applied stress the dislocations might release the trapped hydrogen, since their activation energy is relatively low, and they act as reversible traps. Then the hydrogen will possibly accumulate at regions of high stress created by dislocation pileups. Consequently, the degradation of AM 17-4 SS in a hydrogen environment is predicted to occur through the HEDE mechanism. It should be noted, however, that in the present study AM 17-4 SS was investigated in the as-printed condition, and further study would need to be done in order to examine the interactions of hydrogen with AM 17-4 SS after various HTs.

5 Conclusions

-

The resistance of AM 17-4 SS to HAC is better than that of the CM counterpart, despite the higher amount of absorbed hydrogen. This is attributed to the stronger hydrogen trapping sites, the presence of retained austenite and the absence of Nb-rich precipitates in the AM 17-4 SS.

-

Oxide inclusions have no significant effect on the susceptibility of AM 17-4 SS to HE.

-

The environmental degradation of AM 17-4 SS in a hydrogen-containing environment will most likely occur through the HEDE mechanism.

-

AM processing of martensitic SS creates stronger hydrogen traps, thus improving the resistance of the AM SS to HE at higher hydrogen uptakes, compared to CM SS.

Data availability

The data that support the fndings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Davis JR (1994) ASM specialty handbook: stainless steels, ASM International®, Materials Park. OH, USA

Oriani RA (1978) Hydrogen embrittlement of steels. Ann Rev Mater Sci 8:327–357

Venezuela J, Liu Q, Zhang M, Zhou Q, Atrens A (2016) A review of hydrogen embrittlement of martensitic advanced high strength steels. Corros Rev 34:153–186

Dayal RK, Parvathavarthini N (2003) Hydrogen embrittlement in power plant steels. Sadhana 28:431–451

Robertson IM, Sofronis P, Nagao A, Martin ML, Wang S, Gross DW, Nygren KE (2015) Hydrogen embrittlement understood. Metall Mater Trans B 46:1085–1103

Lynch S (2012) Hydrogen embrittlement phenomena and mechanisms. Corros Rev 30:105–123

Pressouyre GM, Bernstein IM (1978) A quantitative analysis of hydrogen trapping. Metall Trans A 9A:1571–1580

Pressouyre GM (1980) Trap theory of hydrogen embrittlement. Acta Metall 28:895–911

Silverstein R, Eliezer D, Tal-Gutelmacher E (2018) Hydrogen trapping in alloys studied by thermal desorption spectrometry. J Alloy Comp 747:511–522

Bajaj P, Hariharan A, Kini A, Kürnsteiner P, Raabe D, Jägle EA (2020) Steels in additive manufacturing: a review of their microstructure and properties. Mater Sci Eng A 772:138633

Meredith SD, Zuback JS, Keist JS, Palmer TA (2018) Impact of composition on the heat treatment response of additively manufactured 17–4 PH grade stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 738:44–56

Henry TC, Morales MA, Cole DP, Shumeyko CM, Riddick JC (2021) Mechanical behavior of 17–4 PH stainless steel processed by atomic diffusion additive manufacturing. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 114:2103–2114

DebRoy T, Wei HL, Zuback JS, Mukherjee T, Elmer JW, Milewski JO, Beese AM, Wilson-Heid A, De A, Zhang W (2018) Additive manufacturing of metallic components – process, structure and properties. Prog Mater Sci 92:112–224

Kamat AM, Pei Y (2019) An analytical method to predict and compensate for residual stress-induced deformation in overhanging regions of internal channels fabricated using powder bed fusion. Addit Manuf 29:100796

Sabooni S, Chabok A, Feng SC, Blaauw H, Pijper TC, Yang HJ, Pei YT (2021) Laser powder bed fusion of 17–4 PH stainless steel: a comparative study on the effect of heat treatment on the microstructure evolution and mechanical properties. Addit Manuf 46:102176

Burns DE, Kudzal A, McWilliams B, Manjarres J, Hedges D, Parker PA (2019) Investigating additively manufactured 17–4 PH for structural applications. J Mater Eng Perform 28:4943–4951

Kovacs SE, Miko T, Troiani E, Markatos D, Petho D, Gergely G, Varga L, Gacsi Z (2023) Additive, manufacturing of 17–4PH alloy: tailoring the printing orientation for enhanced aerospace application performance. Aerospace 10:619

Vunnam S, Saboo A, Sudbrack C, Starr TL (2019) Effect of powder chemical composition on the as-built microstructure of 17–4 PH stainless steel processed by selective laser melting. Addit Manuf 30:100876

Cheruvathur S, Lass EA, Campbell CE (2016) Additive manufacturing of 17–4 PH stainless steel: post-processing heat treatment to achieve uniform reproducible microstructure. JOM 68:930–942

Hu Z, Zhu H, Zhang H, Zeng X (2017) Experimental investigation on selective laser melting of 17–4PH stainless steel. Opt Laser Technol 87:17–25

Sun Y, Hebert RJ, Aindow M (2018) Effect of heat treatments on microstructural evolution of additively manufactured and wrought 17–4PH stainless steel. Mater Des 156:429–440

Yang Z, Liu Z, Liang J, Su J, Yang Z, Zhang B, Sheng G (2021) Correlation between the microstructure and hydrogen embrittlement resistance in a precipitation-hardened martensitic stainless steel. Corros Sci 182:109260

Shen S, Li X, Zhang P, Nan Y, Yang G, Song X (2017) Effect of solution-treated temperature on hydrogen embrittlement of 17–4 PH stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng, A 703:413–421

Chiang WC, Pu CC, Yu BL, Wu JK (2003) Hydrogen susceptibility of 17–4 PH stainless steel. Mater Lett 57:2485–2488

Yan Q, Yan L, Pang X, Gao K (2022) Hydrogen trapping and hydrogen embrittlement in 15–5PH stainless steel. Corros Sci 205:110416

Schutz P, Martin F, Auzoux Q, Adem J, Rauch EF, Wouters Y, Latu-Romain L (2022) Hydrogen transport in 17–4 PH stainless steel: Influence of the metallurgical state on hydrogen diffusion and trapping. Mater Charact 192:112239

Schutz P, Latu-Romain L, Martin F, Auzoux Q, Adem J, Wouters Y, Ravat B, Menut D (2023) Onto the role of copper precipitates and reverted austenite on hydrogen embrittlement in 17–4 PH stainless steel. Mater Charact 202(2023):113044

Fan YH, Zhao HL, Weng KR, Ma C, Yang HX, Dong XL, Guo CW, Li YG (2022) The role of delta ferrite in hydrogen embrittlement fracture of 17–4 PH stainless steel. Int J Hydrogen Energy 47:33883–33890

Alnajjar M, Christien F, Bosch C, Wolski K (2020) A comparative study of microstructure and hydrogen embrittlement of selective laser melted and wrought 17-4 PH stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 785:139363

Shoemaker TK, Harris ZD, Burns JT (2022) Comparing stress corrosion cracking behavior of additively manufactured and wrought 17-4PH stainless steel. Corrosion 78(6):528–546

Guennouni N, Maisonnette D, Grosjean C, Poquillon D, Blanc C (2022) Susceptibility to pitting and environmentally assisted cracking of 17-4PH martensitic stainless steel produced by laser beam melting. Materials 15:7121

ASTM D638–14 ((2014) Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics, ASTM International

ASTM A564/A564M–13 (2013) Standard Specification for Hot-Rolled and Cold-Finished Age-Hardening Stainless Steel Bars and Shapes, ASTM International

Metalnikov P, Eliezer D, Ben-Hamu G, Tal-Gutelmacher E, Gelbstein Y, Munteanu C (2020) Hydrogen embrittlement of electron beam melted Ti–6Al–4V. J Mater Res Technol 9:16126–16134

Metalnikov P, Eliezer D, Ben-Hamu G (2021) Hydrogen trapping in additive manufactured Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Mater Sci Eng A 811:141050

Starr TL, Rafi K, Stucker B, Scherzer CM (2012) Controlling phase composition in selective laser melted stainless steels, Proc Solid Free Fabr Symp, 439–446

Viswanathan UK, Banerjee S, Krishnan R (1988) Effects of aging on the microstructure of 17–4 PH stainless steel. Mater Sci Eng A 104:181–189

Nezhadfar PD, Shrestha R, Phan N, Shamsaei N (2019) Fatigue behavior of additively manufactured 17–4 PH stainless steel: synergistic effects of surface roughness and heat treatment. Int J Fatigue 124:188–204

Sun Y, Hebert RJ, Aindow M (2018) Non-metallic inclusions in 17–4PH stainless steel parts produced by selective laser melting. Mater Des 140:153–162

Li Y, Liu Y, Ch Liu Ch, Li HL (2018) Mechanism for the formation of Z-phase in 25Cr-20Ni-Nb-N austenitic stainless steel. Mater Lett 233:16–19

Maurya AK, Pandey C, Chhibber R (2021) Dissimilar welding of duplex stainless steel with Ni alloys: a review. Int J Pres Ves Pip 192:104439

Strang A, Vodarek V (1996) Z-phase formation in martensitic 12CrMoVNb steel, Mater. Sci Technol 12:552–556

Tavares SSM, Corte JS, Pardal JM (2016) Failure of 17–4PH stainless steel components in offshore platforms. In: Makhlouf ASH, Aliofkhazraei M (eds) Handbook of materials failure analysis with case studies from the oil and gas industry. Elsevier, Butterworth-Heinemann, pp 353–370

Pantazopoulos G, Papazoglou T, Psyllaki P, Sfantos G, Antoniou S, Papadimitriou K, Sideris J (2004) Sliding wear behaviour of a liquid nitrocarburised precipitation-hardening (PH) stainless steel. Surf Coat Technol 187:77–85

Narita N, Altstetter CJ, Birnbaum HK (1982) Hydrogen-related phase transformations in austenitic stainless steels. Metall Trans A 13:1355–1365

Du Y, Gao X, Lan L, Qi X, Wu H, Du L, Misra RDK (2019) Hydrogen embrittlement behavior of high strength low carbon medium manganese steel under different heat treatments. Int J Hydrogen Energy 44:32292–32306

Jin XK, Xu L, Yu WC, Yao KF, Shi J, Wang MQ (2020) The effect of undissolved and temper-induced (Ti, Mo)C precipitates on hydrogen embrittlement of quenched and tempered Cr-Mo steel. Corros Sci 166:108421

Hebsur MG, Moore JJ (1985) Influence of inclusions and heat treated microstructure on hydrogen assisted fracture properties of AISI 316 stainless steel. Eng Fract Mech 22:93–100

Silverstein R, Eliezer D (2017) Mechanisms of hydrogen trapping in austenitic, duplex, and super martensitic stainless steels. J Alloy Comp 720:451–459

Silverstein R, Eliezer D, Glam B, Eliezer S, Moreno D (2015) Evaluation of hydrogen trapping mechanisms during performance of different hydrogen fugacity in a lean duplex stainless steel. J Alloy Comp 648:601–608

Silverstein R, Eliezer D, Boellinghaus T (2018) Hydrogen-trapping mechanisms of TIG-welded 316L austenitic stainless steels. J Mater Sci 53:10457–10468

Park Y, Maroef I, Landau A, Olson D (2002) Retained austenite as a hydrogen trap in steel welds. Welding J 81:27–35

Dabah E, Lisitsyn V, Eliezer D (2010) Performance of hydrogen trapping and phase transformation in hydrogenated duplex stainless steels. Mater Sci Eng A 527:4851–4857

Chun YS, Kim JS, Park KT, Lee YK, Lee CS (2012) Role of ε martensite in tensile properties and hydrogen degradation of high-Mn steels. Mater Sci Eng A 533:87–95

Drexler A, Depover T, Leitner S, Verbeken K, Ecker W (2020) Microstructural based hydrogen diffusion and trapping models applied to Fe–C–X alloys. J Alloy Compd 826:154057

Kamilyan M, Silverstein R, Eliezer D (2017) Hydrogen trapping and hydrogen embrittlement of Mg alloys. J Mater Sci 52:11091–11100

Novak P, Yuan R, Somerday BP, Sofronis P, Ritchie RO (2010) A statistical, physical-based, micro-mechanical model of hydrogen-induced intergranular fracture in steel. J Mech Phys Solids 58:206–226

Shi R, Chen L, Wang Z, Yang X-S, Qiao L, Pang X (2021) Quantitative investigation on deep hydrogen trapping in tempered martensitic steel. J Alloys Compd 854:157218

Perng TP, Altstetter CJ (1986) Effects of deformation on hydrogen permeation in austenitic stainless steels. Acta Metall 34:1771–1781

Perng TP, Johnson M, Altstetter CJ (1989) Influence of plastic deformation on hydrogen diffusion and permeation in stainless steels. Acta Metall 37:3393–3397

Krom AHM, Bakker AD (2000) Hydrogen trapping models in steel. Metall Trans B 31:1475–1482

Tal-Gutelmacher E, Eliezer D, Boellinghaus T (2007) Investigation of hydrogen-deformation interactions in β-21S titanium alloy using thermal desorption spectroscopy. J Alloys Compd 440:204–209

Chen L, Xiong X, Tao X, Su Y, Qiao L (2020) Effect of dislocation cell walls on hydrogen adsorption, hydrogen trapping and hydrogen embrittlement resistance. Corros Sci 166:108428

Mishin IP, Grabovetskaya GP, Zabudchenko OV, Stepanova EN (2014) Influence of hydrogenation on evolution of submicrocrystalline structure of Ti-6Al-4V alloy upon exposure to temperature and stress. Russ Phys J 57:423–428

Louthan MR, Derrick RG (1975) Hydrogen transport in austenitic stainless steel. Corros Sci 15:565–577

Du Y, Gao XH, Du ZW, Lan LY, Misra RDK, Wu HY, Du LX (2021) Hydrogen diffusivity in different microstructural components in martensite matrix with retained austenite. Int J Hydrogen Energy 46:8269–8284

Luo HW, Wang XX, Liu ZB, Yang ZY (2020) Influence of refined hierarchical martensitic microstructures on yield strength and impact toughness of ultra-high strength stainless steel. J Mater Sci Technol 51:130–136

Sun B, Krieger W, Rohwerder M, Ponge D, Raabe D (2020) Dependence of hydrogen embrittlement mechanisms on microstructure-driven hydrogen distribution in medium Mn steels. Acta Mater 183:313–328

Zhang L, Li Z, Zheng J, Zhao Y, Xu P, Zhou C, Li X (2013) Effect of strain-induced martensite on hydrogen embrittlement of austenitic stainless steels investigated by combined tension and hydrogen release methods. Int J Hydrogen Energy 38:8208–8214

Wang Y, Wang X, Gong J, Shen L, Dong W (2014) Hydrogen embrittlement of catholically hydrogen-precharged 304L austenitic stainless steel: effect of plastic pre-strain. Int J Hydrogen Energy 39:13909–13918

Fan H, Zhang B, Yi HL, Hao GS, Sun YY, Wang JQ, Han E-H, Ke W (2017) The role of reversed austenite in hydrogen embrittlement fracture of S41500 martensitic stainless steel. Acta Mater 139:188–195

Sofronis P, Robertson IM (2006) Viable mechanisms of hydrogen embrittlement - a review. AIP Conf Proc 837:64–70

Lee Y, Gangloff RP (2007) Measurement and modeling of hydrogen environment-assisted cracking of ultra-high-strength steel. Metall Mater Trans A 38A:2174–2190

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Vladimir Ezersky for the TEM measurements.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Sami Shamoon College of Engineering.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ben-Hamu, G., Metalnikov, P. & Eliezer, D. The effect of low hydrogen content on hydrogen embrittlement of additively manufactured 17–4 stainless steel. Prog Addit Manuf (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-024-00599-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-024-00599-9