Abstract

Literacy as specified in the recent PIAAC survey (OECD 2013) is separated into competence levels. This allows a comparison of adults performing on literacy Level I and below versus those performing on Level IV and above. The PIAAC survey also contains variables on participation in adult education. Core findings confirm the Matthew effect for participation rates, but not for training hours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Adult education and training on literacy level one and below

Adult eduction and training provide opportunities to develop or maintain cognitive skills needed both at work and in everday life. Knowledge about the kind of training used by those performing on the PIAAC literacy scale on Level I and below is relevant for policy makers and practitioners who want to tailor their supply structures towards their needs. Following the publication of the results of large-scale assessments, several countries realized that the share of the population on Level I and below was much higher than thought. Many launched programs or strategies to improve their populations’ skill levels. There is growing concern that those who were left behind in initial schooling and vocational education participate less than average in adult education as well. Some countries set out benchmarksFootnote 1 for participation rates with regard to formal and non-formal adult education and training. All findings in this paper, which are not quoted from other publications, have been computed in a common publication project with the OECD Paris under the lead of William Thorn, published as Education Working Paper 131 (Grotlüschen et al. 2016). Analyses were mostly made with the STATA software and the PIAAC repest module, covering the complete dataset. This paper mostly relies on results that have not been published in the common report. The report focuses Level I and below because this cut-off is the main reference in Europe (EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy 2012). Adult education and training is defined according to the Classificaton of Learning Activities (European Commission and Eurostat 2006).Footnote 2

The focus in this article lies on the subpopulations on PIAAC literacy or numeracy Level I and below and their relation to adult education and training, to informal learning at work and learning strategies. The literacy Level I and below subpopulation is 15.5 % of the adult population (international average). Roughly a third of the low literate do participate in adult education, which is seen as unsatisfactory in several countries. To improve this situation, the research questions are:

-

Do formal or non-formal formats attract larger shares of the low literate subgroup?

-

Which formats are interesting for the subgroup, e. g. workshops, individual lessons or e‑learning?

-

How does the subpopulation work and which kinds of workplace support training activities?

-

What is the role of informal learning at work?

-

What are the reasons for participation and non-participation?

-

Is there more demand than provision or vice versa? Is training needed, are jobs challenging?

-

Do Level I and below subpopulations use learning strategies? Is there a need to improve these?

Three international adult education surveys, which are the European Adult Education Survey (AES), the EU Labor Force Survey (EU LFS) and the Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS) regularly point to socio-demographic differences including initial education and clearly indicate that adult education depends on employment (Kaufmann and Widany 2013). Most of the variables’ impact decreases if employment is controlled. Raw figures indicate that differences seem to decrease in order of their appearance to public awareness. Gender differences have lessened and partly vanished, age differences are decreasing, migration differences haven’t decreased so far but may do so soon. Class differences – defined by formal education, employment and income – have not decreased.Footnote 3

Several national literacy surveys focus literacy and numeracy Level I according to their own definitions and methodology. The French case shows that literacy rises while numeracy skills decline in the population (Jonas 2012). The English Skills for Life surveys in 2003 and 2011 also shifted the awareness from literacy towards numeracy (DfES 2003; BIS Department for Business Innovation and Skills 2011). The German survey LEO integrated reading and writing and pointed at the problem that most Level I difficulties consist in writing, not in reading (Grotlüschen and Riekmann 2012).

International literacy research claims that the Level I and below subpopulation is on average neither unemployed nor “foreign-born”, as a major European consortium points out in their report (EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy 2012). PIAAC shows differences between subpopulations of 24 countries. As the OECD Skills Outlook reports, the likelihood of participating in adult education and training (OECD 2013, p. 209) varies according to Level of literacy proficiency.

2 Adult education and training – general results

Participation rates in adult education and training do not necessarily translate into outcomes; however, they are a good indicator for lifelong learning activities in a country and have a long research tradition. According to PIAAC, the overall participation rates with regard to formal and non-formal adult education and training differ substantially. In some countries, over 70 % of the population participate regularly in lifelong learning (OECD 2013). Across all countries, it is the high skilled population that participate more in formal and non-formal adult education.

With a focus on the low-skilled population only, the average is 31.3 %; the highest participation rates reach nearly 50 % of the subpopulation in Norway, some 44 % in Denmark and more than 42 % in Sweden. The lowest participation rates are found in Poland, the Slovak Republic and Italy. The large range of the data – from 14 to 49 % – shows that countries can learn from well performing entities.

The reason for varying participation is not only to be seen in educational policies. Participation rates correlate with employment (see above). The countries under consideration have very different labor markets. The unemployment rates in the three countries with the highest overall participation rates are all below 10 % of the population (Norway: 3.2 %, Sweden 8.0 %, Denmark 7.5 %; cf. Rammstedt 2013, p. 211).

The German survey on the low-skilled population (Level-One Survey LEO, Grotlüschen and Riekmann 2012) shows comparable results regarding the participation rates (LEO: 28 % of the low-skilled population participate in non-formal adult education and training). From LEO, it is known that the majority of courses focus on forklift or truck driving licences, work security issues, welding licences or – for immigrants – German language courses (Bilger 2012). All these areas are subject to regulation and law and the attendees of these courses are usually obliged to participate.

2.1 Selectivity and efficacy

The question of whether adult education and training is efficient or not is relevant for funding and provision strategies. When access to training is non-selective, it is likely that progress will be slower and show less impact than when access is selective and thus allows only the better performers among a subpopulation (e. g. the unemployed) to enter the learning group.

When funders expect training providers to demonstrate the effects of training, providers tend to select participants more carefully and prefer to train those that have greater chances of performing well. This so-called “creaming effect” is quite well known and often criticized by practitioners. In this type of situation, all parties, the funders, the participants and the suppliers face something of a dilemma. Funding strategies, for example, may emphasize both efficacy and non-selectivity, i. e. the targeting of the most in need (i. e. those least likely to succeed). Correlations between training participation and (literacy) performance based on cross-sectional data always represent the outcome of the combined effects of selection and efficacy.

The raw regression coefficient from literacy onto formal and non-formal training is 26.2 points (international average). If socio-demographic and educational variablesFootnote 4 are controlled for, the regression coefficients decrease substantially from 26.2 points on the PIAAC scale to 6.2 points (international average). This indicates that the relation between literacy and training is mostly influenced by education, employment and socio-demographics and that only a small effect remains, representing at the same time the selectivity and efficacy of adult education according to forms of learning.

2.2 Participation gaps by forms of learning (formal, non-formal, informal)

The forms of adult education show very different participation rates. The gaps between low and high skilled subpopulations also differ with regard to the form of learning. The gap between low-skilled population and high skilled population by forms of learning is:

-

Formal Adult Education and Training: Participation rates 9.1 % versus 18.4 %.

-

Non-formal Adult Education and Training: Participation rates 27.1 % versus 66.6 %.

-

Informal Learning at Work (employed only): Proportion of those with highest agreement (top two): 36.0 % on Level I and below versus 36.9 % on Level IV and above.

The PIAAC-index “Learning at Work” combines agreements to statements about keeping up to date or learning by doing. The overall distribution of agreement to the statements was divided into five percentiles so the percentages show the shares of people belonging to the percentiles. Among the low-skilled, 19 % belong to highest quintile (which means these 19 % agree nearly fully (80 to 100 %) with the statements on learning at work). The top two quintiles add up to roughly one third of the low-skilled population who most clearly agree with the question on whether they learn at work.

The gaps within formal adult education and non-formal education are large compared to learning at work among the working low-skilled population. This is usually discussed as a highly selective entry into non-formal education. The small gap regarding learning at work is possibly caused by the reduced subpopulation of only those who work. This leads to the conclusion that the selectivity is mostly caused by participation in the labor market.

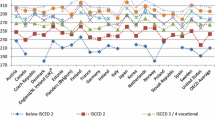

The international comparison shows that the overall gaps differ between countries (Fig. 1). Both the shares of Level I participants as well as the gaps between high and low literate participants are interesting starting points for further comparative research.

3 Non-formal adult education and training

The overall gaps lie between the low and high skilled populations, not between the countries. Averages show that some 27 % of the low-skilled population participates in non-formal education while more than 66 % of the high skilled does so. For Numeracy, the shares are 28 and 66 % respectively. Evidence shows a strong influence of the workplace for non-formal training enrolment (the influence of the workplace on participation in adult education and training is well known in adult education research and has been repeatedly confirmed [CEDEFOP-European Center for the Development of Vocational Training 2010; Kaufmann et al. 2014; Friebel et al. 2000; Brüning and Kuwan 2002; Kuper et al. 2013]).

3.1 More training hours on level I than on higher levels

According to PIAAC, low performing adults (Level I and below) who participate in non-formal education receive more training hours than high performing adults (Level IV and above) who participate in non-formal education. The training volume shows that the mean for Level I performing adults lies at some 150 hours (international average for literacy performance) while this is 10 hours less on Level IV/5 and another 20 hours lower on Level II and III. The distribution is bimodal. It does not include formal education. An explanation for this could be the long-term course programs provided by job agencies for the Level I population as well as the language programs for migrants recently arrived.

The distribution by country shows that the peaks are on different Levels. In several northern European countries, the duration is highest on Level I, in England and Northern Ireland it is not significantly different by Level. Other countries like Korea and Spain have peaks on Level IV and above. In Australia, Poland and the US the Levels II or III receive the highest amount of training hours, but this does not necessarily differ significantly from the neighbouring Levels.

3.2 Participation by type of non-formal learning

Non-formal education consists of seminars and workshops, private lessons and open or e‑learning formats. The index is made up of these four variables. The gap between the low and high skilled population is quite well known. Supposedly the causality behind the correlation runs in both directions: high performers have fewer problems entering adult education, and adult education helps to maintain or improve their skills.

Being low-skilled in literacy or numeracy affects the chances of participation in non-formal adult education only slightly. The pattern stays the same. The types of non-formal adult education differ widely, with on the job training and seminars or workshops being more attractive and accessible than e‑learning or private lessons. This differs across countries and Levels as can be seen in the OECD report (Grotlüschen et al. 2016). The country-specific participation rates by type of non-formal education show a large variety in provision and demand for non-formal education. The post-Soviet countries that recently changed their systems do not show a common pattern (i. e. not offering seminars or focusing on distance learning). Fig. 2 demonstrates the importance of on the job training and the wide access gap in seminars and workshops. The smaller types of non-formal learning (open and distance learning and private lessons) have higher participation rates in northern countries than elsewhere. Seminars and workshops hint at an adult education system with public and commercial training institutions that are accessible to all who fulfil the conditions for the training offer. All countries seem to have this infrastructure for Level IV and above performers. But several countries do not find Level I and below performers in their seminars and workshops.

3.3 Non-formal education by types of employment

As employment seems to be very influential for participation in adult and continuing education, a closer look at the type of employment is provided.

The majority of performers at Level I and below do not feel challenged enough in their jobs (international average: 77 %, see below), even at their very low literacy skill Level. That indicates monotonous workplaces. On the other hand, the skills available do not seem to match the requirements for all of the workplaces, as roughly a fourth to a third of the Level I and below performers express their need for more training (international average: 28 %, see below).

Certain features of jobs are associated with greater chances of participating in non-formal training. Overall, low-skilled individuals working in skilled occupations, in the public sector, in more stable employment contracts and in jobs that have requirements for tertiary qualifications, have higher rates of participation in non-formal education and training. In addition, low-skilled workers in jobs that involve greater flexibility for the employee have higher rates of training participation.

3.3.1 Quality of employment correlates with participation in adult education

While the impact of employment on formal and non-formal learning is clear, there are differences within the employed sections of the low-skilled population as well. Depending on which qualification a job would require nowadays, the share of participants rises significantly. Blue collar and elementary occupations lead to less further education than white collar jobs and skilled occupations. Job satisfaction and participation also correlate positively and significantly. The causality remains unclear. It may lie in the job itself as a third factor influencing both satisfaction and participation rates as well as in the satisfying effects of adult education.

3.3.2 Less flexible jobs correlate with low adult education participation rates

The workplace itself can be monotonous and dependent on other peoples’ decisions, as well as flexible and to a certain extent subject to one’s own decisions and influence. Deciding on the sequence of your tasks or the speed and rate of work indicates some influence and independence at the workplace, but monotony is the everyday reality for more than a third of the Level I and below subgroup, compared to some 20 % of the overall population. Low flexibility seems to reduce the likelihood of further education as the participation rates decrease from roughly 46 to roughly 36 %.

Some 42 % of the Level I and below employees have the opportunity to decide what time they start work and when they leave (compared to 53 % in the overall population). This kind of individual control over working hours might be necessary to attend courses and seminars and correlates positively with participation.

3.3.3 Security of employment correlates with participation in adult education

In case the working subpopulation of the low-skilled is employed in the public sector, their rates of participation in adult education are significantly higher (55 %) than in the private sector (38 %). While stable and fixed term contracts do not differ in terms of participation rates (44 %), the agencies and temporary employment opportunities offer significantly lower chances for adult education (29 %). The decrease of company size (as reported by the interviewees) does not lead to activities with regard to further education among the low-skilled population (participation rate: 44 %). Expanding companies offer more opportunities to their staff (52 %). Perhaps they face more training needs because of newly employed staff that needs initial inhouse training.

4 The difficulties to get access to training

The share of low-skilled people who expressed an interest in training mostly report that the reasons for not starting are lack of support, being busy with work and family issues and the costliness of the training. Those who did participate state doing their job better as the most relevant reason. On the other hand, being obliged to attend training is a crucial factor for participation as well. This reveals paradox effects of jobs as the core reason for training and – at the same time – being busy at work as the core hindering factor.

4.1 Training wanted, but not started

Among the low-skilled population we find between 4 and nearly 30 % who wanted training, but did not start. The international average is 17.1 %, for the numeracy low-skilled population it is 17.7 %. The highest shares with more than one quarter of the numeracy low-skilled population agreeing to the statement (training wanted) are in the USA (28.1), Sweden (25.8), Denmark (25) and Ireland (24.5). This changes slightly if literacy is used for the definition of the subpopulation, with Sweden, USA, Ireland and Spain ranking highest. Within the high skilled population the average is 35.9 % (literacy) and 34.2 % (numeracy). In nearly all countries, the proportion of those who reported wanting training but not starting ranges from a quarter to nearly half of the high skilled population. The USA has the highest values, with more than 50.5 % in both domains (literacy and numeracy).

The large differences between the low-skilled populations’ relatively low values and the high skilled populations’ values between 20 and 50 % show that this is more than a social desirability effect. Activating these sections of the subpopulation would double the figures of adult education participation among the low-skilled population for many countries.

4.2 Reasons for non-participation within the low-skilled population

Work, family and numerous non-specified reasons (other) are reported to be the most hindering factors, followed by financial issues, structural barriers, not meeting the criteria and unforseen circumstances. This is followed by one in five persons facing or anticipating financial problems in connection with adult education and training. Even if sometimes the course is free of charge, people assume it must cost something, because they are already used to having to pay everywhere (cf. Heinemann 2014).

Time constraints are mentioned as a strong barrier. But as we know from qualitative research, this might be an escape category: people tend to report time issues; but the non-reported, hidden reason is that they see no thematic relation between the training and their everyday challenges (Grotlüschen 2003).

Regarding the unspecified reasons (other), this indicates either people cannot tell what kept them from starting or they have reasons which are not covered by the answer options. Early research found that time, money and lack of connections was the famous formula for non-participation in the 1960s (Strzelewicz et al. 1966). From the new century on, fear of being too old or too unprepared are reported according to the theory and research on “social fields” (Barz and Tippelt 2004) or with regard to non-participants and never-participants (Schröder et al. 2004). Four types of abstinence have been classified (Bolder and Hendrich 2000) and the development of thematic interest has been distinguished into phases (Grotlüschen 2010). Postcolonial and intersectional approaches have also been used to pinpoint migrant women’s reasons for learning, suggesting the importance of “citizenship capital” (Heinemann 2014).

4.3 Reasons for participation within the low-skilled population

The international averagesFootnote 5 show that “doing the job better” and “improving career prospects” is ticked by more than 45 % of those low-skilled who participate in adult education. Another 20.9 % state they were obliged to participate. The threat of losing the job is not an issue. This might mean that the jobs are secure or that adult education would not change the job situation anyway. Amongst unqualified or low qualified adults the latter idea is common (Grotlüschen and Brauchle 2004; Schiersmann 2006).

4.4 Job requirements: not challenged enough or needing more training

The variables used here are controversially discussed as the measurement of skills mismatch (Perry et al. 2014). But the question in this section is not the mismatch between skills and jobs, the question is whether and how low performers engage in further education.

Level I and below performers might find themselves in monotonous workplaces where they are not challenged enough and therefore have neither the opportunity nor the need for informal learning activities at work. Those who do not feel challenged enough are some 77 % of the literacy Level I and below population (international average), ranging from nearly 88 % in Germany to 63 % in Finland, Japan being an outlier with 28 %. Being insufficiently challenged and having very low literacy skills allows the conclusion that the workplaces under consideration require rather few skills. Similarily, the underchallenged 86 % of the Level IV/V performers will be interpreted as low requirements for highly performing employees.

In case the Level I and below performers enter more qualified jobs and find themselves equipped with fewer skills than required, this should lead to the necessity of training. One would expect that the lower the skills, the higher the need for training would be. Some 28 % on Level I and below say they need more training, while this figure increases slowly but steadily up to 36 % of the Level IV/V performers.

On Level I and below, 77 % feel underchallenged while 28 % need training. The latter will either try to get non-formal training or start to improve their skills informally. The following section shows that a quarter up to a third of them reports learning at work every day.

4.5 Learning strategies and adult education

Six items form an indicator called “Learning Strategies”. The index is abbreviated as “Readiness to Learn” in the questionnaire. The theoretical discussion is published in the Conceptual Framework underlying the Background Questionnaire (OECD 2011, p. 18), but some of the indicators are not available in the final questionnaire anymore, so the direct link between theoretical idea in 2011 and the published index in 2013 remains unclear. Results should be interpreted carefully.

The overall result shows an international pattern where Asian countries versus post-Soviet and Western countries seem to differ. This may be a cultural pattern underlying the self-reported answers.

Bivariate correlations between learning strategies and participation rates are low (in this case computed via the IDB Analyzer Software and with SPSS). The international averages turn out to be:

-

0.11 for formal adult education (s.e. < 0.00, range from 0.04 in the Czech Republic to 0.19 in Estonia).

-

0.14 for non-formal education (s.e. < 0.00, range from 0.08 in Norway to 0.21 in Estonia).

-

0.21 for informal learning at work (s.e. < 0.00, range from 0.13 in Korea to 0.30 in Austria).

Learning strategies of the Level I and below subpopulation have rather small correlations with their participation in adult education and learning. This is striking and may need further investigation.

The theoretical approach sketched out in the conceptual framework of the background questionnaire would suggest that learning strategies, which form an index based on the theory of metacognition, should be quite influential for learning (OECD 2011). On the other hand, this might differ between learning outcomes and participation rates.

5 Summary of findings

Adult education and training is on the rise in the long-term view but in all countries it is divided according to competence and qualification. PIAAC confirms the well-known Matthew Effect, but the gaps differ between countries. Countries with high shares in training participation among the low literate subpopulation tend to be the countries with low unemployment rates. The composition of literacy Level I and below also differs substantially as well as countries’ supply structures for recently arrived migrants.Footnote 6

Training duration does not necessarily confirm the Matthew Effect. The international average shows that Level I and below performers receive more training hours if they enter adult education. This differs considerably across countries.

PIAAC allows study of the relation between proficiency and adult education by controlling the other predictors. The causality is two-directional: the more literate parts of the population receive easier access to adult education and training (selectivity) while those who attend adult education and training preserve and improve their literacy proficiency (efficacy). Findings indicate that countries perform rather differently in this respect. The types of supply – formal, non-formal, informal – also show quite different results in this combination of selectivity and efficacy. Non-formal learning has the strongest positive relation with literacy, while informal learning is negatively associated with literacy. That means literacy Level I and below performers agree that the learning required for their job takes place at work.

Regarding the forms of provision, the results show very little formal adult education and training, the average rate being below 10 % (range 3 to 18 %) compared to more than 18 % within Level IV and above performers and more than 30 % Level I participation rate in non-formal learning. It could be worth communicating to the target group which pathways are open after initial formal education, where they lead to and what kind of support structures exist.

Non-formal learning is easier to access for low literate adults. The type of non-formal education matters (e-learning and private lesson sversus on the job training or seminars). Job quality, flexibility and security seem to be relevant as well.

-

The quality of employment, sketched out with the variables qualification requirement, position and satisfaction, correlates slightly, but significantly positive with non-formal learning opportunities. Monotonous jobs can lead to a decrease in skills.Footnote 7

-

The flexibility of work, understood as the possibility to make decisions on the sequence of tasks, about how to do your work, about speed and how to organize working hours within a day, correlates differently with participation rates. Here high and medium flexibility correlates most with the participation in non-formal leraning.

-

A third subsection of indicators were selected to hint at the feeling of security of employment with regard to contract stability, the increase or decrease of the company as well as the public or private sector of employment: Higher stability seems to improve participation rates even if only the employed subpopulation of Level I and below is taken into consideration.

These three subsections were conducted with the employed among the literacy Level I and below. The differences between qualified and unquailified positions, flexible and monotonous jobs and more or less feeling of job security are significant, but remain small. On average, 66 % of the low literate adults are employed, this is the majority, but still below average.Footnote 8

Practitioners from companies and training institutions also state that the target groups under consideration do not necessarily show a large demand for training, but PIAAC data show that it could be possible to engage more low performers in learning.

-

On average, 17 % of the literacy Level I and below report they wanted training in the past 12 months but did not start. This differs substantially by country (4 to 28 %). The rate is much lower than among highly literate adults.

-

Reasons for non-participation are lack of time because of family and job commitments as well as the cost. “Other” remains a large category.

-

Reasons for participation are mostly job related (do my job better, job promotion). Upskilling to prevent job loss does not seem to be relevant for this population.

Overall, workplace requirements drive people to upskill and at the same time being busy at the workplace prevents people from finding the time to do this. This paradox holds throughout domains and Levels.

The data represent two characteristics of low literate meeting high or low expectations at work. Monotonous workplaces and never having to learn at work correspond for a large part of the target group. Some 77 % of the Level I and below subpopulation feels underchallenged at work (compared to 86 % of the Level IV and above). This reflects monotonous and unqualified workplaces.

On the other hand those low literate groups who find themselves in qualified jobs agree they need training and this is confirmed by their activity in learning at work. Some 28 % agrees to need further training. Those in need of training or upskilling receive it at work.

Active learning strategies are widespread even amongst the low-skilled. The majority of the low-skilled population has to be considered at least partly as capable of and interested in learning or using learning strategies. But there is a minority of low literate and numerate adults who even do not use the most widespread techniques, e. g. 18.5 % of the low-skilled population very rarely search for additional information. Learning strategies have significant, but low bivariate correlation effect sizes with learning at work, non-formal adult education and formal adult education, indicating that those ready to learn do not necessarily end up in doing so.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

As a whole, stereotypes about literacy or numeracy Level I and below parts of the populations contain assumptions about how willing and capable this group is with regard to further adult education and training. The answer is the same than in the other chapters of the OECD Thematic Report “Adults with Low Proficiency” (Grotlüschen et al. 2016), even if the picture is more difficult to see. The overall average participation rate is 46 %, the average literacy Level I and below participation rate is at 31.3 %. The assumption that none of the affected would continue to learn is therefore false. Roughly one third does so. That is much more than those who arrive in literacy provision.

Provision is often focused around the domain of reading and writing. But participation in adult education within this group will often focus how to handle machines, vehicles or techniques, care for safety regulations, or how to use most recent healthcare approaches. Language and literacy is not the reason why people attend these seminars and national strategies should focus on overall participation in adult education, not on literacy provision only.

In case lifelong learning is accepted as an appropriate strategy for adopting changes in technology and globalization, countries often raise awareness by benchmarking participation rates they want to reach. By benchmarking overall participation rates one could also benchmark for the low literate or numerate, for example to reach at least the international average in participation. If more than 30 % of the subgroup participates in adult learning and another 17 % wanted but didn’t start, the range between those two figures is the area where benchmarks could be placed. It could be interesting to collect benchmarks throughout the participating countries.Footnote 9

Formal, non-formal learning and learning strategies are – on average – positively associated with proficiency with small positive effect sizes, indicating that the more proficient enter adult education and preserve or improve their skills. The question whether adult education and training provision can influence proficiency has to be addressed with longitudinal data. But from PIAAC data it is already clear that the contemporary approaches’ impact does not exceed a few points on the PIAAC scale. Countries have to look carefully at their training provision and continue to improve the access to formal and non-formal training as well as the quality. The latter also raises the question of professional adult education trainers and their payment.

Informal learning at work, which is less selective than other forms, could be used as a starting point for more strategic pathways for upskilling, new combinations of informal access and pathways to more formal, broadened, long-term and certified further education seem to take the best out of both approaches: access via informal learning, efficacy via non-formal and formal learning.

General information about lifelong learning at the end of compulsory school could be of vital importance as this is the last stage where “those out of reach” can be reached systematically. This might also mean that either teacher education has to include knowledge about lifelong learning opportunities or guidance institutions have to be available that can be visited in the last school year.

Employment requires and fosters non-formal learning and it is a barrier because of the lack of time. The findings point at a large demand of training that is hindered by time constraints and costliness. Overall, workplace requirements drive people to upskill and at the same time being busy at the workplace prevents people from finding the time to upskill as well. This paradox holds throughout domains and levels.

In case work requires learning, the Level I and below group seems to match it, perhaps because the skills available are not enough to meet job demands. Still the amount of non-learning employees on literacy Level I and below seems remarkable. This may be caused by jobs with very low requirements and therefore the risk for the workforce to lose skills by not using them. Exposure do demanding tasks is a relevant motivator for both informal and non-formal learning.

Last, but not least, learning strategies show that literacy Level I and below groups do have a considerable set of strategies to get by, but the extent of use is not as large as among the more proficient adults and they do not lead to course participation. In case learning strategies are agreed as an important part of lifelong learning activity, the policy makers and practitioners could take into consideration to explicitly train these strategies and raise awareness for them.

Notes

The German government wants 50 % of the population to participate in adult education and training and wants the low educated to reach participation rates of some 30 %. The reference survey is the Adult Education Survey, carried out every three to five years.

Literacy-related nonrespondents have not been excluded. The international averages include all participating countries. Calculations have been carried out with the Stata PIAAC Repest Module (Francois Keslair, OECD) which includes weights and plausible values.

Multivariate analyses with data of the AES show that gender differences are not significant once employment is controlled for, age differences remain significant for the 50+ and migration effects remain significant for the youngest cohort of migrants aged 18 to below 30 (Kuper et al. 2013).

The values are controlled for age, gender, employment status, education, parents’ education, self-reported health status, test language and native language and ICT use at home.

If the distribution is split by country, the categories often have less than 60 cases.

See David Mallows’ findings in Grotlüschen et al. (2016).

See Stephen Reder’s findings in Grotlüschen et al. (2016).

See David Mallows’s findings for more details about employment and family status within the subpopulations and compared to the average adult populations in Grotlüschen et al. (2016).

Lisbon program benchmark (12 % participation rate in the last 4 weeks according to Lifelong Learning ad hoc module), the High Level Group of Literacy Experts (maximum of 15 % share of the population performing on Level I and below) or benchmarks based on the AES (German average aim: 50 % participation rate in the last 12 months and 30 % average within the low educated).

References

Barz, H., & Tippelt, R. (Eds.). (2004). Weiterbildung und soziale Milieus in Deutschland. Adressaten- und Milieuforschung zu Weiterbildungsverhalten und -interessen, vol. 2. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann.

Bilger, F. (2012). (Weiter-)Bildungsbeteiligung funktionaler Analphabet/inn/en Gemeinsame Analyse der Daten des Adult Education Survey (AES) und der leo. In A. Grotlüschen & W. Riekmann (Eds.), Alphabetisierung und Grundbildung: Vol. 10. Funktionaler Analphabetismus in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der ersten leo. – Level-One Studie (pp. 254–275). Münster: Waxmann.

BIS – Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2011). 2011 Skills for Life Survey: Headline Findings (BIS Research Paper 57). www.bis.gov.uk. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

Bolder, A., & Hendrich, W. (2000). Fremde Bildungswelten: Alternative Strategien lebenslangen Lernens. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Brüning, G., & Kuwan, H. (2002). Benachteiligte und Bildungsferne – Empfehlungen für die Weiterbildung. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann. http://www.gbv.de/dms/hebis-darmstadt/toc/104779950.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

CEDEFOP – European Center for the Development of Vocational Training (2010). Employer-provided vocational training in Europe: evaluation and interpretation of the third continuing vocational training survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

DfES (2003). The Skills for Life survey: a national needs and impact survey of literacy, numeracy and ICT skills. Norwich. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32277/11-1367-2011-skills-for-life-survey-findings.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy (2012). Final Report. http://ec.europa.eu/education/policy/school/doc/literacy-report_en.pdf

European Commission & Eurostat (2006). Classification of Learning Activities. Manual. Luxemburg. http://www.uis.unesco.org/StatisticalCapacityBuilding/Workshop%20Documents/Education%20workshop%20dox/2010%20ISCED%20TAP%20IV%20Montreal/NFE_CLA_Eurostat_EN.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

Friebel, H., Epskamp, H., & Knoblauch, B. et al. (2000). Bildungsbeteiligung: Chancen und Risiken; eine Längsschnittstudie über Bildungs- und Weiterbildungskarrieren in der “Moderne”. Schriftenreihe der Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Politik, Hamburg, vol. 4. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Grotlüschen, A. (2003). Virtuell und selbstbestimmt? Internationale Hochschulschriften, 417. Münster: Waxmann.

Grotlüschen, A. (2010). Erneuerte Interessetheorie. Vom Zusammenspiel pragmatischer und habitueller Achsen bei der Interessegenese. Theorie und Empirie Lebenslangen Lernens. Wiesbaden: VS.

Grotlüschen, A., & Brauchle, B. (2004). Bildung als Brücke für Benachteiligte. Hamburger Ansätze zur Überwindung der Digitalen Spaltung: Evaluation des Projekts ICC – Bridge to the Market. Münster: LIT.

Grotlüschen, A., & Riekmann, W. (Eds.). (2012). Alphabetisierung und Grundbildung: Vol. 10. Funktionaler Analphabetismus in Deutschland: Ergebnisse der ersten leo. – Level-One Studie. Münster: Waxmann.

Grotlüschen, A., Mallows, D., Reder, S., & Sabatini, J. (2016). Adults with low proficiency in literacy or numeracy: the survey of adult skills (PIAAC) thematic report (OECD education working papers no. 131). http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/adults-with-low-proficiency-in-literacy-or-numeracy_5jm0v44bnmnx-en?crawler=true. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

Heinemann, A. M. (2014). Teilnahme an Weiterbildung in der Migrationsgesellschaft: Perspektiven deutscher Frauen mit “Migrationshintergrund” (1st edn.). Theorie bilden, vol. 33. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Jonas, N. (2012). Pour des générations les plus récentes, les difficultés des adultes diminuent à l’écrit, mais augmentent en calcul (INSEE PREMIERE No. 1426 Décembre 2012). http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?ref_id=ip1426. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

Kaufmann, K., & Widany, S. (2013). Berufliche Weiterbildung – Gelegenheits- und Teilnahmestrukturen. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 16(1), 29–54.

Kaufmann, K., Reichart, E., & Schömann, K. (2014). Der Beitrag von Wohlfahrtsstaatsregimen und Varianten kapitalistischer Wirtschaftssysteme zur Erklärung von Weiterbildungsteilnahmestrukturen bei Ländervergleichen. Report. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 37(2), 39–54.

Kuper, H., Gnahs, D., & Hartmann, J. (2013). Resümee – Weiterbildungsberichterstattung und Weiterbildungsforschung mit dem deutschen AES. In F. Bilger, D. Gnahs, J. Hartmann & H. Kuper (Eds.), Theorie und Praxis der Erwachsenenbildung. Weiterbildungsverhalten in Deutschland. Resultate des Adult Education Survey 2012 (pp. 351–355). Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann.

Kuper, H., Unger, K., & Hartmann, J. (2013). Multivariate Analyse zur Weiterbildungsbeteiligung. In F. Bilger, D. Gnahs, J. Hartmann & H. Kuper (Eds.), Theorie und Praxis der Erwachsenenbildung. Weiterbildungsverhalten in Deutschland. Resultate des Adult Education Survey 2012 (pp. 95–107). Bielefeld: wbv.

OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2011). PIAAC Conceptual Framework of the Background Questionnaire Main Survey. Ref. Doc.: PIAAC(2011_11)MS_BQ_ConceptualFramework.docx.

OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2013). OECD Skills Outlook 2013. First Results from The Survey of Adult Skills. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264204256-en

Perry, A., Wiederhold, S., & Ackermann-Piek, D. (2014). How can skill mismatch be measured? methods, data, analyses, 8(2), 137–174. doi:10.12758/mda.2014.006.

Rammstedt, B. (Ed.) (2013). Grundlegende Kompetenzen Erwachsener im internationalen Vergleich: Ergebnisse von PIAAC 2012. Münster (u.a.): Waxmann.

Schiersmann, C. (2006). Profile lebenslangen Lernens: Weiterbildungserfahrungen und Lernbereitschaft der Erwerbsbevölkerung. DIE spezial. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann.

Schröder, H., Schiel, S., & Aust, F. (2004). Nichtteilnahme an beruflicher Weiterbildung: Motive, Beweggründe, Hindernisse. Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann.

Strzelewicz, W., Raapke, H.-D., & Schulenberg, W. (1966). Bildung und gesellschaftliches Bewußtsein: Eine mehrstufige soziologische Untersuchung in Westdeutschland. Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grotlüschen, A. Literacy level I and below versus literacy level IV and above. ZfW 39, 255–270 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-016-0068-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40955-016-0068-7