Abstract

Loneliness is prevalent during emerging adulthood (approximately 18–25 years) and is an important issue given it has been linked to poorer physical and mental health outcomes. This preregistered scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the literature on loneliness in emerging adulthood, including the (a) conceptualization and measurement of loneliness, (b) loneliness theories used, (c) risk factors and outcomes examined, (d) sex-gender differences observed, and (e) characteristics of emerging adult samples previously researched. Following the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines, seven electronic databases were searched for articles focused on loneliness published from 2016 to 2021, where the mean age of participants was ≥ 18 and ≤ 25 years. Of the 4068 papers screened, 201 articles were included in the final review. Findings suggest the need for a clearer consensus in the literature regarding the conceptualization of loneliness for emerging adults and more qualitative work exploring emerging adults’ subjective experiences of loneliness. Results highlight an over-reliance on cross-sectional studies. Over two thirds of articles described their sample as university students and the median percentage of females was 63.30%. Therefore, fewer cross-sectional studies using convenience samples and more population-based, longitudinal research is needed to understand the factors predicting loneliness over time, and the downstream impact of loneliness for emerging adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Loneliness is commonly defined as the unpleasant feeling that accompanies the experience of perceiving the quantity or quality of one’s social relationships as inadequate (Perlman & Peplau, 1981). While loneliness is common across the lifespan, it is particularly prevalent in young, or emerging adults (Barreto et al., 2021; Hawkley et al., 2022). Prevalence estimates from the United Kingdom suggest up to 31% of emerging adults experience loneliness at least some of the time, and 5–7% feel lonely often (Matthews et al., 2019). In the United States, about 24% of emerging adults report feeling lonely “a lot of the day” (Witters, 2023), and almost one in three (32.6%) emerging adults in India report high levels of loneliness (Banerjee & Kohli, 2022). Emerging adult loneliness has been independently associated with indictors of poorer physical and mental health, including hypertension, anxiety and depressive symptoms, alcohol problems, and long-term mental illness (Christiansen et al., 2021). Therefore, loneliness is an important issue in emerging adulthood and good quality research is a key step in offsetting this potential harm. However, the literature is lacking a review that summarizes important aspects of the research in emerging adulthood, including how loneliness is conceptualized and measured, which loneliness theories are used, which risk factors and outcomes of loneliness have been examined, if there are sex-gender differences in loneliness, and the characteristics of emerging adults previously included in research in this area. This information is needed to provide a basis for rigorous loneliness research for this group. Therefore, this scoping review addresses this gap.

Loneliness in Emerging Adulthood

The transition from adolescence to full-fledged adulthood in developed countries is longer and more challenging to define than in previous points in history. This is primarily due to engaging in traditional markers of adulthood such as marriage and parenthood at later ages, and the widespread uptake of education beyond secondary school (Arnett, 2024). Arnett’s theory of emerging adulthood (2000, 2024) describes a distinct life-stage, from late teens through mid-to-late twenties. When age ranges are needed to describe emerging adulthood, ages 18–25 years are considered a conservative estimate, as few 18–25-year-olds have entered stable adulthood (Arnett, 2024). However, the specific age of the beginning and end of this life stage is variable, and critics have noted that the concept of emerging adulthood is heavily influenced by cultural, socioeconomic, and educational factors (Shanahan & Longest, 2009). Culture plays an important role in variation in the length and content of emerging adulthood, and the markers of established adulthood (Arnett, 2024). For instance, in keeping with the Chinese tradition of collectivism, a key marker of adulthood for Chinese emerging adults is the ability to financially support their parents, whereas this is not typically endorsed in the United States (Nelson & Luster, 2015).

Despite these critiques, there is general agreement that the prolonged entry into adulthood has resulted in significant developmental challenges (Côté, 2014). Typical features of emerging adulthood include identity exploration and greater self-focus, which may lead to instability in emerging adults’ social networks (Arnett & Mitra, 2020). Major social transitions occurring during young, or emerging, adulthood include moving out of the parental home, or beginning university or employment (Arnett, 2024). An age-normative perspective suggests that the timing of ongoing physical and psychological changes, unique societal expectations, and key social transitions places emerging adults at increased risk of loneliness (Qualter et al., 2015). Given the vulnerability to loneliness in this age group, robust research is needed to understand loneliness in emerging adulthood.

Recognizing that emerging adults are at particular risk for loneliness emphasizes the need to consider factors associated with loneliness in this group. However, the research priorities in relation to examining risk factors and outcomes of loneliness in emerging adulthood are unclear. One existing scoping review explored the literature on loneliness in youth (aged 15–24 years; Adib & Sabharwal, 2023); however, the review was limited in scope with a specific focus on social support and relationship factors like parenting bonds, both of which were inversely associated with loneliness. The extent to which other factors that may be associated with loneliness, for example mental health issues and technology use (Matthews et al., 2019), are focused on in the literature with emerging adults have not been reviewed. Additionally, gender differences in loneliness are important for understanding who is most vulnerable to loneliness. While one comprehensive meta-analysis suggested that young adult males were lonelier than females (Maes et al., 2019), this study considered a much wider age range (21–40 years) as young adulthood. Therefore, summarizing sex-gender differences in emerging adulthood merits consideration. Finally, persistent sampling bias issues mean that loneliness research generalized to emerging adults may be based on convenience samples of university undergraduates which may not represent diverse groups (Nielsen et al., 2017). It is unclear to what extent specific groups who disproportionately experience loneliness, such as migrants and people with poor health (Barreto et al., 2023), are focused on in the literature. Understanding who we study when we study emerging adults is of importance; therefore, a summary of the characteristics of emerging adults included in loneliness research is needed to support robust research in this area.

Loneliness

A key aspect of understanding loneliness in emerging adulthood is a clear conceptualization and distinction from related concepts. Loneliness is a subjective and emotional experience that is related to, but distinct from social isolation, which is the objective count of social contacts (Wigfield et al., 2022). Across all ages, loneliness is only weakly associated with measures of social contact (Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016). In other words, it is not the mere absence of social contact that impacts lonely individuals, but rather the perceived discrepancy between one’s desired and actual social relationships (Perlman & Peplau, 1981). Loneliness is also distinct from solitude in that loneliness is an unwanted experience, whereas solitude, or being alone, is a conscious choice that is often described as positive (Weinstein et al., 2023). The fact that loneliness and related concepts have been conflated or confused underscores the importance of a clear conceptual understanding of loneliness (Wigfield et al., 2022). Defining and measuring constructs of interest are a foundational part of rigorous research (Flake & Fried, 2020), yet no review has summarized how loneliness has been conceptualized and measured in research with emerging adults.

While loneliness has often been considered unidimensional, there has long been a conceptualization of loneliness as multidimensional. For example, Weiss’ (1973) interactionist approach proposed that relationship-specific types of loneliness arise as the result of deficits in two types of social needs; the need for close attachment figures (emotional loneliness) and the need for a meaningful social network (social loneliness). Social and emotional loneliness are distinct, but correlated, states that arise from different events in a person’s life; emotional loneliness might occur as the result of a romantic relationship breakup, whereas social loneliness can occur after moving to a new town. Recent research demonstrated distinct developmental trajectories for social and emotional loneliness across emerging adulthood (von Soest et al., 2020) and midlife (Manoli et al., 2022). Emotional loneliness levels moderately increase across emerging adulthood, whereas social loneliness substantially decreases throughout emerging adulthood (von Soest et al., 2020), suggesting that multidimensional conceptualizations of loneliness warrant consideration.

The complex nature of loneliness means that several other theories have conceptualized loneliness. Prominent approaches include the cognitive discrepancy model (Peplau & Perlman, 1982), the evolutionary theory (Cacioppo et al., 2006), the psychodynamic theory (Reichmann, 1959), and the existential approach (Moustakas, 1961). Although theoretical approaches to loneliness may overlap in their definitions, they can differ in proposed causes of loneliness. For example, the cognitive discrepancy model considers the influence of personality, cultural, and situational factors and proposes that loneliness is caused by a person appraising a deficiency in their social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). The evolutionary theory of loneliness suggests that loneliness arises as a signal of social pain to motivate reconnection and is transient for most individuals (Cacioppo et al., 2006; Spithoven et al., 2019). Other theories, such as the socio-cognitive model, focus on the mechanisms through which loneliness persists and impacts health (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). However, no review has summarized how loneliness has been conceptualized and what theories of loneliness have been used in the emerging adult literature.

Current Study

Although there has been an acceleration of research on loneliness in emerging adulthood and recognition that loneliness is an important issue for young people’s health, there is no existing scoping review summarizing key aspects of this literature. The goal of this preregistered scoping review was to provide a descriptive overview of the existing literature on loneliness in emerging adulthood to inform future research. This review was guided by the following research question: What is known from the available literature about loneliness in emerging adults? The research sub-questions included how has loneliness been conceptualized and measured in research in emerging adults (Research Question 1)?, what loneliness theories have been used in research on loneliness in emerging adulthood (Research Question 2)?, what risk factors and outcomes for loneliness have been previously examined in emerging adulthood (Research Question 3)?, what is the evidence on sex-gender differences in loneliness in emerging adults (Research Question 4)?, and what are the characteristics of emerging adults included in previous loneliness research (Research Question 5)?.

Methods

Given the focus on loneliness in emerging adulthood, a topic with increasing and disparate literature, a scoping review, rather than a systematic review, was considered most appropriate (Munn et al., 2018). This scoping review was informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2015) and Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) seminal work. The reporting of results was guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). This review was preregistered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/c7ke9). To complete a feasible review, some amendments to the protocol were necessary and are outlined below (labelled as Amendment to Protocol 1–4).

Identifying Relevant Studies

Following preliminary searches of two databases (PsycInfo and Medline) to become familiar with key terms, the following electronic databases were searched in June 2021; Scopus, PubMed, PsycArticles, PsycInfo, Medline, ScienceDirect, and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA). The search was updated in April 2022 to source articles published until the end of 2021. The search terms describe the concepts loneliness and young, or emerging, adults (see Table 1). The search was tailored to the specific requirements of each electronic database (see Supplementary Material 1 for example of a database search).

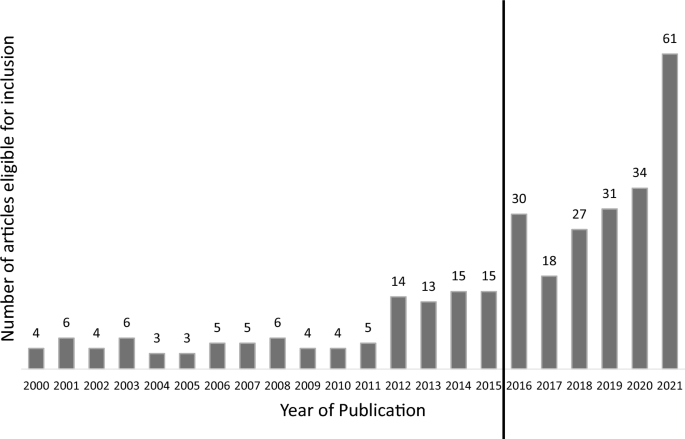

Initially, the search included peer-reviewed journal articles published between the years 2000–2021. Given that Arnett’s (2000) seminal work on emerging adulthood was published in the year 2000, it was expected to yield more research on the target population after this year. Using this year limit, 313 articles were eligible for inclusion in the review. However, following discussion among the authors, a consensus was reached that given the large volume of relevant literature, a year limit of 2016–2021 was sufficient for a feasible narrative summary of the recent literature on loneliness in emerging adulthood (Amendment to Protocol 1). The increase in research interest on loneliness in emerging adulthood in 2016 is shown in Fig. 1.

Grey literature in the form of difficult-to-locate studies or reports by organizations interested in youth mental health (e.g., Jigsaw, SpunOut. i.e., National Youth Council of Ireland) were searched for by posting general requests (in October 2021) for relevant information on Twitter and mentioning relevant youth and research network organizations (“@organization”) in such tweets to encourage reposting (Adams et al., 2016). Additionally, a large loneliness research network placed a request for literature in their newsletter distributed to experts in the field (in December 2021). No additional eligible articles that had not already been identified were located.

The study protocol outlined the aim for an additional search for reports by relevant organizations interested in youth mental health by identifying organization websites using a search engine like Google. After a preliminary search for this type of grey literature, consensus was reached that following grey literature search strategies outlined by others (i.e., Adams et al., 2016) was a satisfactory search for grey literature (Amendment to Protocol 2). Grey literature was a complementary part of the search strategy and considering the large volume of identified peer-reviewed articles, peer-reviewed literature was prioritized in this review. This decision was also influenced by the consideration that when using search engines like Google, even if the search engine search was replicable, other researchers may not retrieve the same results on replication, as Google indexes websites based on several predictors: geographical location, previous search history, popularity, and so on (Bates, 2011).

Study Selection

-

(a)

Research where loneliness was a key focus of the work was included. This was determined by the inclusion of loneliness in an aim, objective, research question, or hypothesis. Quantitative studies that reported on loneliness under a broader term were included; for example, studies measuring or reporting on the construct of loneliness but describing it in the aims or objectives under broader terms like “psychological well-being”, “mental health”, or similar. Following preliminary screening, additional inclusion criteria outlined that where it was difficult to determine if loneliness was a key focus of quantitative research, articles must have reported analysis beyond the prevalence of loneliness to be included. With regards to qualitative research, if it was unclear if loneliness was a key focus of the work, articles must have discussed loneliness as a key concept in the introduction to be included (Amendment to Protocol 3).

-

(b)

To identify the types of available evidence in the area (Munn et al., 2018), qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods, systematic reviews, and meta-synthesis articles were included.

-

(c)

Articles where the age of participants was ≥ 18 and ≤ 25 years were included. Articles that included a wider age range but reported a mean age ≥ 18 and ≤ 25 years were included. Following preliminary screening, further clarification was added to the inclusion criteria detailing where studies were longitudinal in design, included studies must report loneliness for age ≥ 18 and ≤ 25 years at least one time point (Amendment to Protocol 4).

-

(d)

Included research articles were not limited by population groups, specific life-events, specific samples, setting, or geographical location.

-

(e)

Included articles were not limited by measure of loneliness.

-

(f)

Included articles were published in English (the researchers’ only language).

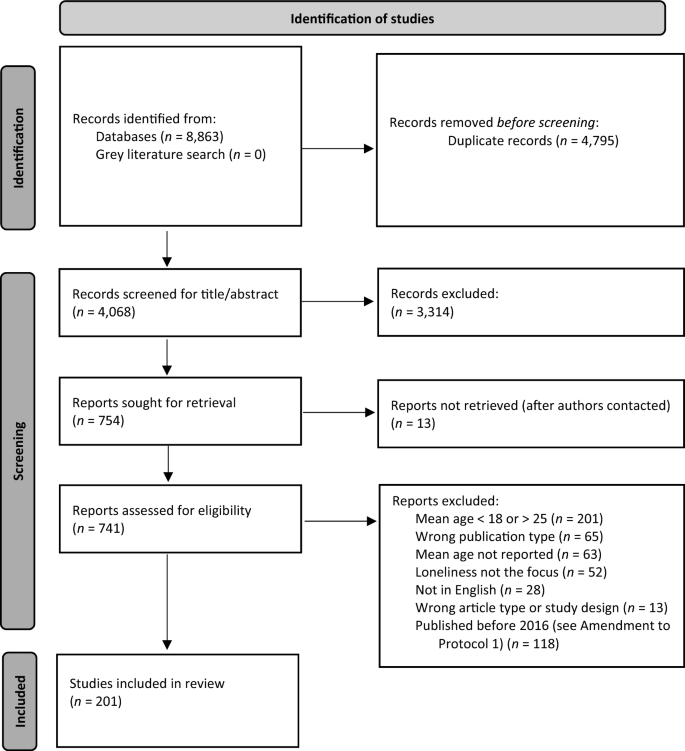

Narrative reviews and loneliness scale development articles were excluded, as well as editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces, dissertations, and book chapters (labelled as “wrong article type or study design” in Fig. 2). Figure 2 summarizes the study selection process. In total, 8,863 articles were retrieved from the electronic database search. EndNote X9 software was used to manage references and facilitate duplicate record removal. Following duplicate record removal, 4,068 articles were screened by title and abstract on Rayyan (https://rayyan.ai/, Ouzzani et al., 2016). Fifty percent of titles and abstracts were blindly screened by a second reviewer (SS), inter-rater agreement was 98.00%. After title and abstract screening, 754 articles were included for full text screening. During full-text screening, EK contacted authors via ResearchGate to request their full-text articles and 13 of these requests were unsuccessful. Second reviewers (SS, MMG, AG) screened 50% of full-text articles. Inter-rater agreement for full-text articles was 94.19%. All disagreements were resolved through discussion; a further reviewer (AMC) was consulted on six (0.79%) decisions during full text screening.

Data Charting

Data charting was conducted for all included articles by one reviewer (EK) by entering information into Microsoft Excel tables. The data charting form was pre-piloted on a random selection of articles and was refined to ensure all relevant information was extracted. A proportion of data charting (10%) was checked by a second reviewer (MMcG) for accuracy. The data charting form included (a) bibliographic information, (b) key study and subject matter information, (c) the conceptualization and measurement of loneliness, (d) the loneliness theories included, (e) the examined predictors and outcomes for loneliness, (f) sex-gender differences, and (g) characteristics of emerging adult samples included. The detailed list of information for which data were charted can be found in Supplementary Material 2.

Summarizing, and Reporting the Findings

Given that the aim of this review was to provide a descriptive summary of the available literature on loneliness in emerging adulthood, the quality of included studies was not assessed. All findings were included in the narrative review. Checks were completed to ensure the findings of the included systematic review were not duplicated in the results. Tables and narrative summaries were generated for each research sub-question to present a descriptive overview of the research on loneliness in emerging adulthood (Peters et al., 2015).

Results

Study Context and Characteristics

After eligibility screening, 201 articles were included in the final scoping review. The publication year of included articles ranged from 2016 to 2021 (see Fig. 1). A small number of articles identified in the original search that were published online in 2020 or 2021 but were assigned to a journal issue in 2022 (e.g., Arslan et al., 2022; Hopmeyer et al., 2022) were retained. Research on loneliness in emerging adulthood represents a growing area of research, with almost half (47.26%) of the included articles published in 2020 and 2021.

The sample sizes within original research articles ranged from 4 to 71,988. Studies using quantitative analysis had sample sizes ranging from 35 to 71,988. Qualitative and mixed-method studies conducting qualitative analysis had sample sizes ranging from 4 to 686. The sole included systematic review and meta-analysis (Buecker et al., 2021) included data from 124,855 participants.

Included original articles were conducted in 44 countries across five continents. Thirteen (6.47%) articles included samples from more than one country. Almost half (49.25%) of the articles included samples from Western countries where English is the primary language. The breakdown of how many articles included samples from each country are as follows: USA (k = 66, 32.84%), China (k = 21, 10.45%), UK (k = 18, 8.96%), Turkey (k = 12, 5.97%), Poland (k = 11, 5.47%), Australia (k = 9, 4.48%), Germany (k = 5, 2.49%), Denmark (k = 4, 1.99%). The Netherlands, South Korea, Canada, Hungary, South Africa, and Spain were each included in three (1.49%) articles. Singapore, Greece, Republic of Ireland, Israel, and Bangladesh were each included in two (1.00%) articles. Finland, Italy, Northern Ireland, Norway, Slovakia, Austria, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Sweden, Thailand, Malaysia, and Nigeria were each included in one (0.50%) article. Included original research articles had a general community or university setting (including online surveys) (k = 186, 92.54%), or were conducted in a clinical or laboratory setting (e.g., an outpatient clinic) (k = 13, 6.47%).

Study Design

Included articles were quantitative (k = 190, 94.53%), mixed method (k = 8, 3.98%), qualitative (k = 1, 0.50%), systematic review and meta-analyses (k = 1, 0.50%), and qualitative protocol (k = 1, 0.50%) studies. The following study designs were included; cross-sectional (k = 151, 75.12%), longitudinal (k = 44, 21.89%), and experimental (k = 4, 1.99%).

Covid-19 Related Studies

Thirty (14.93%) articles explored loneliness in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic. Most studies (k = 23) explored the prevalence of loneliness or the association of loneliness with factors such as life satisfaction, mental health, quality of life during pandemic restrictions, or in the broader context of Covid-19 pandemic. For example, one study compared the reported prevalence of mental health issues and loneliness in emerging adults in the UK and China during the pandemic (Liu et al., 2021), reporting higher loneliness levels in the UK. Some studies (k = 3) examined specific Covid-19 related factors, such as “Covid-19 worry” (Mayorga et al., 2021) and “Coronavirus anxiety” (Arslan et al., 2022), in relation to loneliness. Merolla et al. (2021) used experience sampling and nightly diary surveys to examine how pandemic related anxiety and depressive symptoms manifested in daily perceptions of loneliness; Covid-19 related anxiety was independently associated with greater loneliness. Other studies (k = 2) focused on emerging adults’ relocations during the pandemic (Conrad et al., 2021; Fanari & Segrin, 2021). For example, a longitudinal examination of the extent to which the stressor of forced re-entry from studying abroad during the Covid-19 pandemic was predictive of loneliness in U.S. emerging adults (Fanari & Segrin, 2021). Lastly, one study conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic evaluated two interventions for depression and loneliness (Cruwys et al., 2021).

Research Question 1: Conceptualization and Measurement of Loneliness

Over half (k = 112; 55.72%) of the articles included an explicit definition of loneliness, while another five (2.49%) articles did not formally define loneliness beyond describing it as “perceived social isolation”. Although there was some variation in the way loneliness was defined, for example, describing loneliness as thwarted belongingness (Chu et al., 2016), or as the response to the absence of a relationship (Andangsari & Dhowi, 2016), loneliness was mostly defined as an emotionally unpleasant subjective experience that occurs when a person perceives their social relationships to be inadequate (Perlman & Peplau, 1981). While most (k = 187, 93.03%) articles did not explicitly articulate multiple dimensions of loneliness, 14 (6.97%) articles considered a multidimensional conceptualization of loneliness referring to: social and emotional loneliness (k = 6, 2.98%); social, romantic, and family loneliness (k = 6, 2.98%); isolation, relational connectedness, and collective connectedness (k = 1, 0.50%); romantic loneliness (k = 1, 0.50%).

In total, this scoping review identified 16 measures of loneliness in included articles. The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA; Russell et al., 1980) Loneliness scale was the most employed measure with 161 (80.10%) included articles using a version of this scale. Twelve (5.97%) studies employed a single-item direct measure of loneliness, such as “How lonely did you feel in the past week?”. See Supplementary Material 3 for a full summary of measures of loneliness in included articles.

Most qualitative or mixed-method studies employed semi-structured interviews to explore loneliness (k = 4). Others used open ended survey responses (k = 2), free association task (k = 1), or group discussions and reflective journal responses (k = 1).

Research Question 2: Loneliness Theories

Of the 201 included articles, 29 (14.43%) articles explicitly referenced a loneliness theory in their introduction. While it is possible that some articles implicitly used loneliness theory, articles were considered to have explicitly stated use of loneliness theory if a loneliness theory was referenced in the introduction or aims of the article. Some articles referred to more than one loneliness theory. Seven loneliness theories (see Table 2 for summary) were clearly articulated in loneliness research on emerging adults.

Research Question 3: Risk Factors and Outcomes

A wide range of risk factors and outcomes were examined in association with loneliness in quantitative or mixed-method studies (see Supplementary Material 4 for detail). Most articles examining factors associated with loneliness were cross-sectional in design; longitudinal studies mostly examined loneliness risk factors (k = 25, 12.44%), outcomes were examined in 13 (6.47%) longitudinal studies. Of the longitudinal research examining predictors of loneliness, family and social relationship factors, such as perceived social support, were the most studied risk factors (k = 7). Whereas mental health outcomes, like depression, were the most examined loneliness outcomes in longitudinal studies (k = 6).

Only two longitudinal studies examined within- and between-person variances in loneliness development and the risk and outcome factors associated with changes; one explored the interindividual differences in loneliness development and mental health outcomes in emerging adulthood (Hutten et al., 2021). Another examined longitudinal within- and between-person associations of substance use, social influences, and loneliness among emerging adults who use drugs (Bonar et al., 2022).

Research Question 4: Sex-Gender Differences in Loneliness

In total, 48 (23.88%) studies explored sex-gender differences in loneliness; 40 reported no statistically significant (p > 0.05) difference between male and female loneliness scores, whereas there were eight reports of a significant (p < 0.05) sex-gender difference. Of those that reported significant sex-gender differences, six studies reported higher female loneliness scores and two studies reported higher male loneliness scores. Most studies (k = 4) reporting significant sex-gender differences measured loneliness using the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980), others (k = 2) used the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA; DiTommaso & Spinner, 1993), one used the Loneliness in Context Questionnaire for College Students (Asher & Weeks, 2014), and one used a direct single-item measure. See Table 3 for a complete summary of results.

Research Question 5: Characteristics of Emerging Adult Samples Included in Loneliness Research

The minimum mean age of included studies was 18.00 years, the maximum mean age was 24.78 years. The gender split of included studies ranged from 0% female to 100% female. The median percentage of females in included samples was 63.30%. Over two thirds (k = 137, 68.16%) of articles described their sample as either all or mostly (> 80% of sample) university students. The remaining articles included: general community samples (k = 24, 11.94%), specific samples (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease patients, see Supplementary Material 5 for full details of articles including specific emerging adult samples) (k = 20, 9.95%), population representative samples (k = 11, 5.47%), high school students (k = 6, 2.94%). Some articles (k = 3, 1.49%) did not report information on their sample or sample information was not applicable.

Discussion

Despite an increase of research interest in loneliness in younger age groups and recognition that loneliness is an important issue for emerging adults’ health (Christiansen et al., 2021), there was no existing scoping review summarizing the key aspects of this literature. Reviews can reduce research waste by identifying priority research questions and key gaps in the literature, mapping existing methodological approaches, and clarifying terms and concepts used in the literature (Khalil et al., 2022). Therefore, a scoping review was most appropriate to provide an overview of the literature and identify priorities for future research on loneliness in emerging adulthood.

Three key issues are apparent from this review. First, there was a lack of clear conceptualization of loneliness and prioritization of unidimensional conceptualizations of loneliness in emerging adults, which may be related to the measure of loneliness used. Second, despite the volume of research identified, there was a lack of qualitative research exploring the subjective experience of loneliness. This suggests that the relevance of existing conceptualizations of loneliness for emerging adults who have experienced it remains unclear. Third, while a range of risk factors and outcomes for loneliness have been examined in the literature, research tends to be cross-sectional in design and based on convenience samples of university students. Some additional considerations are noted. Relatively few articles explicitly articulated the use of loneliness theory in their research. Relatively few articles reported on sex-gender differences in loneliness; those that did reported mixed results. Finally, loneliness in emerging adulthood is a growing area of research, with some of this growth due to a focus on loneliness in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Definitions of loneliness in included articles tended to align with Perlman and Peplau’s (1981) widely used definition. Definitions acknowledged both the affective (i.e., the negative emotional experience) and cognitive (i.e., the discrepancy between one’s actual and desired social relations) components of loneliness. A few articles did not explain what is meant by loneliness beyond describing it as perceived social isolation, which does not account for the more complex affective and cognitive aspects of loneliness. While there may be general agreement that loneliness is a subjective emotional experience, the finding that just over half of all articles included a formal definition of loneliness leaves open the possibility that the conceptualization is implicit, poorly understood, or even that loneliness is akin to separate constructs like chosen solitude or objective social isolation. The distinction between concepts like social isolation and loneliness is critical given that across age groups, loneliness is only weakly associated with objective measures of contact with friends and family (Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016). A lack of clear definition of loneliness and conflation with other distinct, but related, terms contribute to conceptual confusion which can have practical implications; for example, policy responses designed for lonely people often aim to increase their social connections, therefore reducing social isolation rather than focusing on reducing experiences of subjective loneliness (Wigfield et al., 2022).

Other loneliness distinctions potentially relevant for understanding loneliness in emerging adulthood include a multi-dimensional conceptualization of social and emotional loneliness (von Soest et al., 2020). These facets are proposed to differentially develop depending on the type of social relationship a person perceives to be inadequate (Weiss, 1973). In addition, existential loneliness was described in recent qualitative work as occurring particularly during young adulthood for some individuals (McKenna-Plumley et al., 2023). A lack of transparent reporting on the conceptualization of loneliness has important implications for its measurement (Flake & Fried, 2020). The finding that few included articles considered different aspects of loneliness, and most did not explicitly discuss whether loneliness was unidimensional or multidimensional, suggests that a unidimensional conceptualization of loneliness is implicit. This is reflected in the frequent use of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980), originally designed as a unidimensional measure. Although the UCLA includes items considered to align with social (11 items) and emotional (7 items) loneliness (Maes et al., 2022), there is no agreed multi-factorial structure of this measure, and using UCLA subscales may not be the best way of measuring multidimensional loneliness; given studies that report the same number of factors differ in terms of the items that are allocated to which factors and the interpretation of the factors (Maes et al., 2022). Additionally, although single-item loneliness measures have shown adequate reliability (Mund et al., 2022) and may be useful as brief screening measures in large-scale surveys (Reinwarth et al., 2023), few articles reported the use of direct single-item loneliness measures; perhaps because of concerns of potential socially desirable responding. Loneliness measurement is central to the validity of studies examining the risk factors and consequences of the experience in emerging adults (Flake & Fried, 2020). Therefore, future research should clearly report the conceptualization and measurement of loneliness.

One approach to achieving consensus on conceptualizations of loneliness in emerging adulthood is through more inductive and exploratory qualitative methods. The only qualitative study eligible for inclusion here focused on young adults living in London’s most deprived areas who described loneliness as being linked to feeling excluded, social media, sadness, and low self-worth (Fardghassemi & Joffe, 2021). While this study gives an insight into loneliness in this demographic, the experiences of loneliness for emerging adults more broadly are lacking in the literature. Further, there is a lack of qualitative research exploring the complexities of the life stage more generally (Schwab & Syed, 2015). Loneliness is an inherently subjective experience. Qualitative methods allow individuals to describe their experience in their own words and are ideally suited for examining how relevant existing conceptualizations of loneliness are for emerging adults. Exploring the meaning of loneliness for those who have experienced it should be a key research priority; a gap which has been addressed among early adolescents (Verity et al., 2021). Although the major features of emerging adulthood may vary between cultures, it is a distinct developmental period of the lifespan (Arnett, 2024). To assume emerging adults share the same social roles, developmental tasks, and societal expectations as adolescents underestimates the increased independence, self-focus, and instability (Arnett et al., 2014) that may be central to loneliness during this stage. Therefore, qualitative research focused on understanding loneliness within the complexities of the life-stage of emerging adulthood is needed.

Of the articles that explicitly considered loneliness theory, most considered approaches that typically focus on individual level characteristics that may increase a person’s risk for loneliness. For example, the evolutionary theory of loneliness (Cacioppo et al., 2006), suggests that younger age groups, due to ongoing development of brain regions associated with cognitive control, may be more sensitive to their social environment and more prone to loneliness beyond the typical features of emerging adulthood (Wong et al., 2018). However, societal, and cultural factors are also likely to contribute to loneliness by influencing a person’s social norms (van Staden & Coetzee, 2010). The cognitive discrepancy theory emphasizes the role of individual attributes, as well as wider cultural norms in how a person perceives their social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Theories of loneliness are not mutually exclusive; developing a causal understanding of loneliness in emerging adulthood likely requires the integration of theory. For example, McHugh Power et al. (2018) synthesized model of loneliness considers both interindividual factors, such as the role of culture in shaping social norms about emerging adults’ social lives, and intraindividual factors, such as changes in the brain regions responsible for social processes, in the development of loneliness. Further, loneliness can be explored within broader theoretical frameworks not specific to loneliness. Developmental approaches can inform research on specific life events and developmental tasks during a particular life stage that may increase a person’s risk of loneliness. For example, employing Erikson’s (1968) psychosocial theory in research exploring the link between identity formation and loneliness in adolescents and emerging adults (Lindekilde et al., 2018).

An age-normative life span perspective suggests that different factors drive loneliness at different ages (Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016). For example, peer relations may be more strongly associated with loneliness during adolescence and emerging adulthood, where friendships are their primary social connections, as opposed to older age groups (Qualter et al., 2015). This aligns with the finding that family and social relationship factors, such as perceived social support from peers, were the most examined risk factors for loneliness in emerging adulthood in longitudinal studies. Perhaps unsurprisingly, aspects of mental health were the most examined outcomes of loneliness. It is also plausible that poorer mental health predicts or has a reciprocal relationship with loneliness during emerging adulthood; emerging adults with depressive symptoms may withdraw from their social relationships or perceive more social rejection (Achterbergh et al., 2020). Despite examining a range of loneliness risk factors and outcomes, included studies were mostly cross-sectional and conducted in Western countries with convenience samples comprising university students. Therefore, the third key issue with this literature highlights the persistent sampling bias and lack of representation and diversity in the field (Nielsen et al., 2017).

Sex-gender differences are also important for understanding who is vulnerable to loneliness. Most studies reported no significant difference. A small number reported a significant difference, mostly reporting higher loneliness among females. Gender differences in loneliness have been hypothesized to emerge in adolescence, where females may be more at risk of adolescent-onset internalizing problems (Martel, 2013). However, a meta-analysis reported a significant, but small, effect of gender on loneliness in young adulthood, finding greater loneliness in males (Maes et al., 2019). The variation of findings in studies examining sex-gender differences have long been attributed to differences in how loneliness is assessed (Borys & Perlman, 1985). Given that few a-priori hypotheses on gender differences in loneliness have been proposed (Maes et al., 2019), future research should report analysis examining sex-gender differences to determine whether sex-gender represents a vulnerability factor for loneliness.

Finally, the findings suggest that loneliness in emerging adulthood is a fast-growing area of research; almost half of all included articles were published in the years 2020 and 2021. Some of this growth was due to the Covid-19 pandemic making the issue of loneliness in younger age groups even more salient than before (Holt-Lunstad, 2021). Although not all who are socially isolated are lonely (Luhmann & Hawkley, 2016), this increased focus on loneliness is unsurprising considering that response measures aimed at mitigating the spread of Covid-19, like social distancing orders, and remote work and education, resulted in less social contact and greater social isolation. One systematic review comparing loneliness before and during the Covid-19 pandemic found an increase in loneliness in younger participant groups (Ernst et al., 2022). However, this increase was from studies including only university student samples; how the pandemic has impacted loneliness during emerging adulthood more generally remains unclear. The theory of emerging adulthood describes a range of developmental transitions to achieve adulthood, such as moving out of the parental home (Arnett, 2024). For some emerging adults, Covid-19 measures may have halted or even reversed steps towards adulthood, resulting in increased loneliness. For example, emerging adults forced to relocate from college campuses to live with parents and guardians experienced greater loneliness than those who did not relocate (Conrad et al., 2021). Life events that impact the achievement of normative social transitions and result in some emerging adults feeling out of sync may be important to consider in the development of loneliness during emerging adulthood.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this review included preregistration of the protocol on Open Science Framework and rigorous methodology following well-established scoping review guidelines (Peters et al., 2015). One potential limitation is the inclusion criteria that articles needed to report a mean age of 18–25 years. This age range is sometimes extended to age 29; however, 18–25 years is appropriate when conservative age ranges are required to describe emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2024). Although a large volume of articles was included, the year limit and lack of grey literature means that there is a possibility that relevant research was not included in this review. While articles were not excluded based on geographical location, included articles were limited to those published in or translated to the English language only, potentially influencing this review’s results.

Future Research

Based on these findings, future studies should provide a clear conceptualization of loneliness, including articulation of loneliness as a uni- or multi-dimensional construct. Studies should specify the theoretical approach (if any) that is informing the research. To generate a clearer understanding of sex-gender differences, these should be reported.

Regarding broad research priorities for loneliness, given the skew towards cross-sectional convenience samples of Western, educated emerging adults, longitudinal research that is population-based or focuses on under-studied cohorts should be prioritized. The current literature does not adequately explore the emergence of specific forms of loneliness, the predictors of loneliness development, and the long-term outcomes of emerging adult loneliness. Developmental trends, the stability of loneliness, and the factors associated with interindividual differences in loneliness during emerging adulthood appear to have also been neglected. Previous research underscores the importance of identifying the characteristics of emerging adults more likely to develop loneliness and the factors that, when changed, correspond to changes in loneliness (Mund et al., 2020). Therefore, longitudinal research should seek to identify emerging adults most at risk of developing sustained or intensely felt loneliness in response to common life events, like finishing school. Also, identifying emerging adults who are at risk of loneliness due to developmental transitions being halted or reversed is a consideration for future longitudinal research. Given potential cultural differences in the markers of adulthood and developmental tasks of emerging adulthood (Nelson & Luster, 2015), research should consider cultural norms in the relationship between social transitions and loneliness during this life stage.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of loneliness during emerging adulthood indicates that loneliness is an issue of importance requiring good quality research. However, no review has provided an overview of key aspects of the literature on loneliness in emerging adulthood. This scoping review provided a descriptive summary of 201 articles on loneliness in emerging adulthood and serves as an initial step highlighting issues with the current research and identifying priorities for future research. Specifically, findings suggest the need for a clearer consensus in the literature regarding the conceptualization of loneliness during emerging adulthood. Second, this review highlights the need for more qualitative work exploring young people’s subjective experiences of loneliness, which is key for understanding the complexities of loneliness during emerging adulthood. Finally, the results indicate that this literature needs fewer cross-sectional studies using convenience samples and more population-based, longitudinal research to understand the factors predicting loneliness over time, and the downstream impact of loneliness for emerging adults.

Data Availability

All data collected for this study were obtained from published peer-review literature. Data extracted to inform this review are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Articles included in the scoping review are marked with (•)

•Aakvaag, H. F., Strøm, I. F., & Thoresen, S. (2018). But were you drunk? Intoxication during sexual assault in Norway. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1539059. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1539059

Achterbergh, L., Pitman, A., Birken, M., Pearce, E., Sno, H., & Johnson, S. (2020). The experience of loneliness among young people with depression: A qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 20, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02818-3

•Adamczyk, K. (2016). An investigation of loneliness and perceived social support among single and partnered young adults. Current Psychology, 35, 674–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9337-7

•Adamczyk, K. (2017). Voluntary and involuntary singlehood and young adults’ mental health: An investigation of mediating role of romantic loneliness. Current Psychology, 36(4), 888–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9478-3

•Adamczyk, K. (2018). Direct and indirect effects of relationship status through unmet need to belong and fear of being single on young adults’ romantic loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 124, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.011

Adams, J., Hillier-Brown, F. C., Moore, H. J., Lake, A. A., Araujo-Soares, V., White, M., & Summerbell, C. (2016). Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: Critical reflections on three case studies. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0337-y

•Akdoğan, R. (2017). A model proposal on the relationships between loneliness, insecure attachment, and inferiority feelings. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.048

•Akdoğan, R., & Çimşir, E. (2019). Linking inferiority feelings to subjective happiness: Self-concealment and loneliness as serial mediators. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.028

•Akhter, M. S., Islam, M. H., & Momen, M. N. (2020). Problematic internet use among university students of Bangladesh: The predictive role of age, gender, and loneliness. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(8), 1082–1093. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1784346

•Al Omari, O., Al Sabei, S., Al Rawajfah, O., Abu Sharour, L., Al-Hashmi, I., Al Qadire, M., & Khalaf, A. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of loneliness among youth during the time of COVID-19: A multinational study. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. https://doi.org/10.1177/10783903211017640

•Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Rice, S., D’Alfonso, S., Leicester, S., Bendall, S., Pryor, I., Russon, P., McEnery, C., Santesteban-Echarri, O., Da Costa, G., Gilbertson, T., Valentine, L., Solves, L., Ratheesh, A., McGorry, P. D., & Gleeson, J. (2020). A novel multimodal digital service (moderated online social therapy+) for help-seeking young people experiencing mental ill-health: pilot evaluation within a national youth e-mental health service. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e17155. https://doi.org/10.2196/17155

•Andangsari, E. W., & Dhowi, B. (2016). Two typology types of loneliness and problematic internet use (PIU): An Evidence of Indonesian measurement. Advanced Science Letters, 22(5–6), 1711–1714. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2016.6740

•Andic, S., & Batigün, A. D. (2021). Development of internet addiction scale based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria: An evaluation in terms of internet gaming disorder. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 32(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.5080/u23194

•Aparicio-Martínez, P., Ruiz-Rubio, M., Perea-Moreno, A. J., Martínez-Jiménez, M. P., Pagliari, C., Redel-Macías, M. D., & Vaquero-Abellán, M. (2020). Gender differences in the addiction to social networks in the Southern Spanish university students. Telematics and Informatics, 46, 101304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101304

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2024). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J., & Mitra, D. (2020). Are the features of emerging adulthood developmentally distinctive? A comparison of ages 18–60 in the United States. Emerging Adulthood, 8(5), 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818810073

Arnett, J. J., Žukauskienė, R., & Sugimura, K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

•Arroyo, A., Segrin, C., & Curran, T. M. (2016). Maternal care and control as mediators in the relationship between mothers’ and adult children’s psychosocial problems. Journal of Family Communication, 16(3), 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1170684

•Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., & Aytaç, M. (2022). Subjective vitality and loneliness explain how coronavirus anxiety increases rumination among college students. Death Studies, 46(5), 1042–1051. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1824204

Asher, S. R., & Weeks, M. S. (2014). Loneliness and belongingness in the college years. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (pp. 283–301). Wiley.

•Babad, S., Zwilling, A., Carson, K. W., Fairchild, V., & Nikulina, V. (2022). Childhood environmental instability and social-emotional outcomes in emerging adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(7–8), NP3875–NP3904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520948147

•Badcock, J. C., Barkus, E., Cohen, A. S., Bucks, R., & Badcock, D. R. (2016). Loneliness and schizotypy are distinct constructs, separate from general psychopathology. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01018

•Balter, L. J., Raymond, J. E., Aldred, S., Drayson, M. T., van Zanten, J. J. V., Higgs, S., & Bosch, J. A. (2019). Loneliness in healthy young adults predicts inflammatory responsiveness to a mild immune challenge in vivo. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 82, 298–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.08.196

Banerjee, A., & Kohli, N. (2022). Prevalence of loneliness among young adults during COVID-19 lockdown in India. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6, 7797–7805.

•Barnett, M. D., Moore, J. M., & Edzards, S. M. (2020). Body image satisfaction and loneliness among young adult and older adult age cohorts. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 89, 104088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104088

•Barnett, M. D., Smith, L. N., Sandlin, A. M., & Coldiron, A. M. (2023). Loneliness and off-topic verbosity among young adults and older adults. Psychological Reports, 126(2), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211058045

Barreto, M., Qualter, P., & Doyle, D. (2023). Loneliness inequalities evidence review. Wales Centre for Public Policy. https://www.wcpp.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/WCPP-REPORT-Loneliness-Inequalities-Evidence-Review.pdf

Barreto, M., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2021). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 110066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110066

Bates, E. M. (2011). Is Google hiding my news? Onlintese-Medford, 35, 64.

BBC Loneliness Experiment. (2018). Who feels lonely? The results of the world’s largest loneliness study. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2yzhfv4DvqVp5nZyxBD8G23/who‐feels‐lonely‐the‐results‐of‐the‐world‐s‐largest‐loneliness‐study

•Beckmeyer, J. J., & Cromwell, S. (2019). Romantic relationship status and emerging adult well-being: Accounting for romantic relationship interest. Emerging Adulthood, 7(4), 304–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818772653

•Bernhold, Q. S., & Giles, H. (2020). The role of grandchildren’s own age-related communication and accommodation from grandparents in predicting grandchildren’s well-being. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 91(2), 149–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415019852775

•Berryman, C., Ferguson, C. J., & Negy, C. (2018). Social media use and mental health among young adults. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89, 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-017-9535-6

•Besse, R., Whitaker, W. K., & Brannon, L. A. (2022). Reducing loneliness: The impact of mindfulness, social cognitions, and coping. Psychological Reports, 125(3), 1289–1304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294121997779

Binte Mohammad Adib, N. A., & Sabharwal, J. K. (2023). Experience of loneliness on well-being among young individuals: A systematic scoping review. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04445-z

•Błachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., Boruch, W., & Bałakier, E. (2016). Self-presentation styles, privacy, and loneliness as predictors of Facebook use in young people. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.051

•Blachnio, A., Przepiórka, A., Wolonciej, M., Mahmoud, A. B., Holdos, J., & Yafi, E. (2018). Loneliness, friendship, and Facebook intrusion. A study in Poland, Slovakia, Syria, Malaysia, and Ecuador. Studia Psychologica, 60(3), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2018.03.761

•Bonar, E. E., Walton, M. A., Carter, P. M., Lin, L. A., Coughlin, L. N., & Goldstick, J. E. (2022). Longitudinal within-and between-person associations of substance use, social influences, and loneliness among adolescents and emerging adults who use drugs. Addiction Research & Theory, 30(4), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2021.2009466

•Borawski, D. (2018). The loneliness of the zero-sum game loser. The balance of social exchange and belief in a zero-sum game as predictors of loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.037

Borys, S., & Perlman, D. (1985). Gender differences in loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11, 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111006

•Bowker, J. C., Bowker, M. H., Santo, J. B., Ojo, A. A., Etkin, R. G., & Raja, R. (2019). Severe social withdrawal: Cultural variation in past hikikomori experiences of university students in Nigeria, Singapore, and the United States. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 180(4–5), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2019.1633618

•Brown, E. G., Creaven, A. M., & Gallagher, S. (2019). Loneliness and cardiovascular reactivity to acute stress in younger adults. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 135, 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.07.471

•Brown, S., Fite, P. J., Stone, K., & Bortolato, M. (2016). Accounting for the associations between child maltreatment and internalizing problems: The role of alexithymia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.008

•Bruehlman-Senecal, E., Hook, C. J., Pfeifer, J. H., FitzGerald, C., Davis, B., Delucchi, K. L., Haritatos, J., & Ramo, D. E. (2020). Smartphone app to address loneliness among college students: Pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 7(10), e21496. https://doi.org/10.2196/21496

•Buchanan, C. M., & McDougall, P. (2021). Predicting psychosocial maladjustment in emerging adulthood from high school experiences of peer victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), NP1810–NP1832. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518756115

•Buckley, C. Y., Whittle, J. C., Verity, L., Qualter, P., & Burn, J. M. (2018). The effect of childhood eye disorders on social relationships during school years and psychological functioning as young adults. The British and Irish Orthoptic Journal, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.22599/bioj.111

•Buecker, S., Mund, M., Chwastek, S., Sostmann, M., & Luhmann, M. (2021). Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(8), 787. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000332

•Burger, C., & Bachmann, L. (2021). Perpetration and victimization in offline and cyber contexts: A variable-and person-oriented examination of associations and differences regarding domain-specific self-esteem and school adjustment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910429

•Burke, T. J., Ruppel, E. K., & Dinsmore, D. R. (2016). Moving away and reaching out: Young adults’ relational maintenance and psychosocial well-being during the transition to college. Journal of Family Communication, 16(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1146724

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Berntson, G. G. (2003). The anatomy of loneliness. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01232

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., & Spiegel, D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

•Cai, L. B., Xu, F. R., Cheng, Q. Z., Zhan, J., Xie, T., Ye, Y. L., Xiong, S. Z., McCarthy, K., & He, Q. Q. (2017). Social smoking and mental health among Chinese male college students. American Journal of Health Promotion, 31(3), 226–231. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.141001-QUAN-494

•Chang, E. C. (2018). Relationship between loneliness and symptoms of anxiety and depression in African American men and women: Evidence for gender as a moderator. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.035

•Chang, E. C., Chang, O. D., Martos, T., Sallay, V., Zettler, I., Steca, P., D’Addario, M., Boniwell, I., Pop, A., Tarragona, M., Slemp, G. R., Shin, J. E., de la Fuente, A., & Cardeñoso, O. (2019). The positive role of hope on the relationship between loneliness and unhappy conditions in Hungarian young adults: How pathways thinking matters! The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(6), 724–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1545042

•Chang, E. C., Liu, J., Yi, S., Jiang, X., Li, Q., Wang, R., Tian, W., Gao, X., Li, M., Lucas, A. G., & Chang, O. D. (2020). Loneliness, social problem solving, and negative affective symptoms: Negative problem orientation as a key mechanism. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110235

•Chang, E. C., Wan, L., Li, P., Guo, Y., He, J., Gu, Y., Wang, Y., Li, X., Zhang, Z., Sun, Y., Batterbee, C. N., Chang, O. D., Lucas, A. G., & Hirsch, J. K. (2017). Loneliness and suicidal risk in young adults: Does believing in a changeable future help minimize suicidal risk among the lonely? The Journal of Psychology, 151(5), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1314928

•Chen, Y. W., Wengler, K., He, X., & Canli, T. (2022). Individual differences in cerebral perfusion as a function of age and loneliness. Experimental Aging Research, 48(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2021.1929748

•Christiansen, J., Qualter, P., Friis, K., Pedersen, S. S., Lund, R., Andersen, C. M., Bekker-Jeppesen, M., & Lasgaard, M. (2021). Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspectives in Public Health, 141(4), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/17579139211016077

•Chu, C., Hom, M. A., Rogers, M. L., Ringer, F. B., Hames, J. L., Suh, S., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). Is insomnia lonely? Exploring thwarted belongingness as an explanatory link between insomnia and suicidal ideation in a sample of South Korean university students. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(5), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5784

•Conrad, R. C., Koire, A., Pinder-Amaker, S., & Liu, C. H. (2021). College student mental health risks during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications of campus relocation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.054

Côté, J. E. (2014). The dangerous myth of emerging adulthood: An evidence-based critique of a flawed developmental theory. Applied Developmental Science, 18(4), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2014.954451

•Creaven, A. M., Kirwan, E., Burns, A., & O’Súilleabháin, P. S. (2021). Protocol for a qualitative study: Exploring loneliness and social isolation in emerging adulthood (ELSIE). International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211028682. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940692110286

•Cruwys, T., Haslam, C., Rathbone, J. A., Williams, E., & Haslam, S. A. (2021). Groups 4 health protects against unanticipated threats to mental health: Evaluating two interventions during COVID-19 lockdown among young people with a history of depression and loneliness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.029

•Cudo, A., Kopiś, N., & Zabielska-Mendyk, E. (2019). Personal distress as a mediator between self-esteem, self-efficacy, loneliness and problematic video gaming in female and male emerging adult gamers. PLoS ONE, 14(12), e0226213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226213

•Curran, T., Janovec, A., & Olsen, K. (2021). Making others laugh is the best medicine: Humor orientation, health outcomes, and the moderating role of cognitive flexibility. Health Communication, 36(4), 468–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1700438

•D’Agostino, A. E., Kattan, D., & Canli, T. (2019). An fMRI study of loneliness in younger and older adults. Social Neuroscience, 14(2), 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2018.1445027

•Dalton, F., & Cassidy, T. (2021). Problematic Internet usage, personality, loneliness, and psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 21(1), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12224

•De la Fuente, A., Chang, E. C., Cardeñoso, O., & Chang, O. D. (2018). How loneliness is associated with depressive symptoms in Spanish college students: Examining specific coping strategies as mediators. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 21, E54. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2018.56

•Dembińska, A., Kłosowska, J., & Ochnik, D. (2022). Ability to initiate relationships and sense of loneliness mediate the relationship between low self-esteem and excessive internet use. Current Psychology, 41(9), 6577–6583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01138-9

•Diehl, K., Jansen, C., Ishchanova, K., & Hilger-Kolb, J. (2018). Loneliness at universities: Determinants of emotional and social loneliness among students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091865

•Dissing, A. S., Hulvej Rod, N., Gerds, T. A., & Lund, R. (2021). Smartphone interactions and mental well-being in young adults: A longitudinal study based on objective high-resolution smartphone data. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 49(3), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820920418

•Ditcheva, M., Vrshek-Schallhorn, S., & Batista, A. (2018). People who need people: Trait loneliness influences positive affect as a function of interpersonal context. Biological Psychology, 136, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.05.014

DiTommaso, E., & Spinner, B. (1993). The development and initial validation of the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA). Personality and Individual Differences, 14(1), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90182-3

•Dong, H., Wang, M., Zheng, H., Zhang, J., & Dong, G. H. (2021). The functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and supplementary motor area moderates the relationship between internet gaming disorder and loneliness. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 108, 110154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110154

•Drake, E. C., Sladek, M. R., & Doane, L. D. (2016). Daily cortisol activity, loneliness, and coping efficacy in late adolescence: A longitudinal study of the transition to college. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(4), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415581914

•Enez Darcin, A., Kose, S., Noyan, C. O., Nurmedov, S., Yılmaz, O., & Dilbaz, N. (2016). Smartphone addiction and its relationship with social anxiety and loneliness. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(7), 520–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1158319

•Engeland, C. G., Hugo, F. N., Hilgert, J. B., Nascimento, G. G., Junges, R., Lim, H. J., Marucha, P. T., & Bosch, J. A. (2016). Psychological distress and salivary secretory immunity. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 52, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.08.017

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W.W. Norton Company.

Ernst, M., Niederer, D., Werner, A. M., Czaja, S. J., Mikton, C., Ong, A. D., Rosen, T., Brähler, E., & Beutel, M. E. (2022). Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. The American psychologist, 77(5), 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001005

•Essau, C. A., & de la Torre-Luque, A. (2021). Adolescent psychopathological profiles and the outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 110, 110330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110330

•Etkin, R. G., Bowker, J. C., & Scalco, M. D. (2016). Associations between subtypes of social withdrawal and emotional eating during emerging adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.059

•Evans, S., Alkan, E., Bhangoo, J. K., Tenenbaum, H., & Ng-Knight, T. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Research, 298, 113819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819

•Fanari, A., & Segrin, C. (2021). Longitudinal effects of US students’ reentry shock on psychological health after returning home during the COVID-19 global pandemic. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 82, 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.04.013

•Fang, J., Wang, X., Wen, Z., & Huang, J. (2020). Cybervictimization and loneliness among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of rumination and online social support. Children and Youth Services Review, 115, 105085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105085

•Fardghassemi, S., & Joffe, H. (2021). Young adults’ experience of loneliness in London’s most deprived areas. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 660791. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660791

•Fernandes, B., Uzun, B., Aydin, C., Tan-Mansukhani, R., Vallejo, A., Saldaña-Gutierrez, A., Nanda Biswas, U., & Essau, C. A. (2021). Internet use during COVID-19 lockdown among young people in low- and middle-income countries: Role of psychological wellbeing. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 14, 100379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2021.100379

Flake, J. K., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Measurement schmeasurement: Questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(4), 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920952393

•Flett, G. L., Goldstein, A. L., Pechenkov, I. G., Nepon, T., & Wekerle, C. (2016). Antecedents, correlates, and consequences of feeling like you don’t matter: Associations with maltreatment, loneliness, social anxiety, and the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.014

•Fransson, M., Granqvist, P., Marciszko, C., Hagekull, B., & Bohlin, G. (2016). Is middle childhood attachment related to social functioning in young adulthood? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12276

•Fumagalli, E., Dolmatzian, M. B., & Shrum, L. J. (2021). Centennials, FOMO, and loneliness: An investigation of the impact of social networking and messaging/VoIP apps usage during the initial stage of the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 620739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620739

•Gan, S. W., Ong, L. S., Lee, C. H., & Lin, Y. S. (2020). Perceived social support and life satisfaction of Malaysian Chinese young adults: The mediating effect of loneliness. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 181(6), 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2020.1803196

•Gonzalez Avilés, T., Finn, C., & Neyer, F. J. (2021). Patterns of romantic relationship experiences and psychosocial adjustment from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 550–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01350-7

•Harriger, J. A., Joseph, N. T., & Trammell, J. (2021). Detrimental associations of cumulative trauma, COVID-19 infection indicators, avoidance, and loneliness with sleep and negative emotionality in emerging adulthood during the pandemic. Emerging Adulthood, 9(5), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211022594

Hawkley, L. C., Buecker, S., Kaiser, T., & Luhmann, M. (2022). Loneliness from young adulthood to old age: Explaining age differences in loneliness. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420971048

•Ho, A. H. Y., Ma, S. H. X., Tan, M. K. B., & Bajpai, R. C. (2021). A Randomized waitlist-controlled trial of an intergenerational arts and heritage-based intervention in Singapore: Project ARTISAN. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 730709. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.730709

•Hoffman, Y. S. G., Grossman, E. S., Bergman, Y. S., & Bodner, E. (2021). The link between social anxiety and intimate loneliness is stronger for older adults than for younger adults. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1246–1253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1774741

•Holmes, L. M., Popova, L., & Ling, P. M. (2016). State of transition: Marijuana use among young adults in the San Francisco Bay Area. Preventive Medicine, 90, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.025

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2021). A pandemic of social isolation? World Psychiatry, 20(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20839

•Hom, M. A., Hames, J. L., Bodell, L. P., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Chu, C., Rogers, M. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). Investigating insomnia as a cross-sectional and longitudinal predictor of loneliness: Findings from six samples. Psychiatry Research, 253, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.046

•Hom, M. A., Stanley, I. H., Chu, C., Sanabria, M. M., Christensen, K., Albury, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). A longitudinal study of psychological factors as mediators of the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation among young adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 15(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.7570

•Hood, M., Creed, P. A., & Mills, B. J. (2018). Loneliness and online friendships in emerging adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.045

•Hopmeyer, A., & Medovoy, T. (2017). Emerging adults’ self-identified peer crowd affiliations, risk behavior, and social–emotional adjustment in college. Emerging Adulthood, 5(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696816665055

•Hopmeyer, A., Terino, B., Adamczyk, K., Corbitt Hall, D., DeCoste, K., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2022). The lonely collegiate: An examination of the reasons for loneliness among emerging adults in college in the western United States and west-central Poland. Emerging Adulthood, 10(1), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696820966110

•Hu, Y., & Gutman, L. M. (2021). The trajectory of loneliness in UK young adults during the summer to winter months of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 303, 114064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114064

•Hudson, D. B., Campbell-Grossman, C., Kupzyk, K. A., Brown, S. E., Yates, B., & Hanna, K. M. (2016). Social support and psychosocial well-being among low-income, adolescent, African American, first-time mothers. Clinical Nurse Specialist CNS, 30(3), 150. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0000000000000202

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

•Hutten, E., Jongen, E. M., Verboon, P., Bos, A. E., Smeekens, S., & Cillessen, A. H. (2021). Trajectories of loneliness and psychosocial functioning. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 689913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689913

•Jattamart, A., & Kwangsawad, A. (2021). What awareness variables are associated with motivation for changing risky behaviors to prevent recurring victims of cyberbullying? Heliyon, 7(10), e08121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08121

•Jeong, Y., & Kim, S. H. (2021). Modification of socioemotional processing in loneliness through feedback-based interpretation training. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106668

•Jia, R., Ayling, K., Chalder, T., Massey, A., Broadbent, E., Morling, J. R., & Vedhara, K. (2020). Young people, mental health and COVID-19 infection: The canaries we put in the coal mine. Public Health, 189, 158–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.10.018

Khalil, H., Peters, M. D., McInerney, P. A., Godfrey, C. M., Alexander, L., Evans, C., Pieper, D., Moraes, E. B., Tricco, A. C., & Munn, Z. (2022). The role of scoping reviews in reducing research waste. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 152, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.09.012

•Kim, E., Cho, I., & Kim, E. J. (2017). Structural equation model of smartphone addiction based on adult attachment theory: Mediating effects of loneliness and depression. Asian Nursing Research, 11(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2017.05.002

•Kircaburun, K., Griffiths, M. D., Şahin, F., Bahtiyar, M., Atmaca, T., & Tosuntaş, ŞB. (2020). The mediating role of self/everyday creativity and depression on the relationship between creative personality traits and problematic social media use among emerging adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9938-0

•Kohls, E., Baldofski, S., Moeller, R., Klemm, S. L., & Rummel-Kluge, C. (2021). Mental health, social and emotional well-being, and perceived burdens of university students during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 643957. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643957

•Kokkinos, C. M., & Antoniadou, N. (2019). Cyber-bullying and cyber-victimization among undergraduate student teachers through the lens of the General Aggression Model. Computers in Human Behavior, 98, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.007

•Kokkinos, C. M., & Saripanidis, I. (2017). A lifestyle exposure perspective of victimization through Facebook among university students. Do individual differences matter? Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.036