Abstract

A systematic scoping review was conducted to explore the current evidence on the experience of loneliness influencing well-being among youths. The electronic databases Scopus, APA PsycINFO, Emerald Insight and One Search were used to identify relevant studies, followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and of the index terms used to describe the article. Reference lists of all shortlisted articles were searched for additional studies. 20 studies (quantitative, qualitative and mixed) published in the English language were identified for inclusion. Findings illustrate that the experience of loneliness is a complex, evolutionary process influenced by relational and environmental factors. Results from the studies identified factors that promote lower experience of loneliness and better well-being in future life stages. Future research can substantiate the issues related to young individuals being socially isolated from others for a prolonged duration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many researchers have focused on Loneliness due to its negative impacts on an individual’s physical and mental health (Cole et al., 2015; Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015) across the lifespan (Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015) and ethnicities (Alcaraz et al., 2019). Loneliness is defined as the subjective feeling of being socially isolated due to a perceived discrepancy between one’s quality and/or quantity of social relationships (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). According to a national survey by Cigna (2018), 46% of the sampled 20,000 American adults aged 18 years and older reported feeling lonely, with the younger generation scoring the highest on loneliness. 43% of the same sampled adults were also found to sometimes or always feel socially isolated from others. With the current COVID-19 situation, the prevalence of loneliness may increase as a result of limited social interactions with others, which if not managed, may be detrimental to physical and mental health. As such, a rise in the prevalence of loneliness may potentially lead to a decrease in well-being, which, in turn, can impose heavy societal burdens. With that being said, well-being has also been a central research focus. Transformative service research (TSR) is one of the research domains that looks towards making improvements in the well-being of individuals and their surrounding environment (Mollenkopf et al., 2020). However, the pandemic has placed tremendous pressure on individuals aged 18 to 64 years old to maintain their well-being while being socially isolated from the rest of the world (Kirzinger et al., 2020).

Gaps in current literature

A systematic overview by Leigh-Hunt et al. (2017) noted that many have attempted to consolidate works surrounding loneliness and well-being. Most syntheses accentuate the measurement of loneliness as an indicator for well-being, as well as the development and effects of loneliness among the older individuals (e.g., Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Stocker et al., 2020). Regardless, only a few have focused exclusively on the factors that drive loneliness in adolescents and young adults (Achterbergh et al., 2020; Korzhina et al., 2022). The reviews also fail to explicate these factors in the context of parent-child relationships and interactions with friends. Put differently, limited works have documented the experience of loneliness among young people based on their early life experiences, and how this may have impacted their current well-being. Thus, mental health practitioners, educators, and even the general public may lack ample, evidence-based insights to deal with the loneliness epidemic among younger individuals especially so during the present times.

There are some realities that urge greater attention to the experience of loneliness among adolescents and young adults. Firstly, although loneliness can affect an individual at any point in life, recent statistics from around the world report individuals aged between 16 to 25 years feeling higher intensities and more frequent feelings of loneliness (Cigna, 2018; Department for Digital, Culture Media & Sport, 2020; Weinberg & Tomyn, 2015). Secondly, very few studies have been conducted to study loneliness among the younger people. Evidence on the risk factors of loneliness and poor well-being that cluster in childhood and adolescence remain scarce. With the adolescence phase being the most risky in terms of the emergence of various mental health problems, experiencing loneliness may be stigmatising due to the adolescent’s strong need to feel connected to others (Pitman et al., 2018). This paper proposes that a deeper insight into the experience of loneliness among young people is needed to better direct prevention and treatment approaches tailored to their needs. This will be done by synthesising evidence on the effects of loneliness on well-being and understanding how the two factors are correlated.

Review question

To manage the rising prevalence of loneliness, Pitman et al. (2018) have advised investment into raising public awareness regarding loneliness among the younger individuals since much has already been done for the older population. Whilst such investments should include increasing support from mental health services, more effort in the early detection of at-risk individuals and the promotion of concomitant loneliness prevention policies and/or practices are needed. In response, the current paper utilised a systematic scoping review methodology to synthesise evidence pertaining to the impact of loneliness on well-being. Another related purpose was to give considerations to the review’s results in providing a deeper understanding of the pathways from loneliness to well-being, and their potential to direct mental health practices. Two questions were derived from the above, which directed focus of the current review: (1) What factors contribute to experience of loneliness among young people? (2) Do existing works help us to construct a pathway between loneliness and well-being among young people?

Systematic scoping review

Scoping reviews broadly summarise current research findings and identify any gaps within a given research topic (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Such reviews are particularly useful when researchers lack the time and resources to undertake a more rigorous systematic review (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Systematic reviews on the other hand are narrowly focused on finding answers by identifying, evaluating and synthesising all relevant studies on a particular topic (Agarwal et al., 2019; Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). The present paper merges the two procedures to find answers to specific questions from a broad body of peer reviewed literature. This paper follows the five components of the six-step approach outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) to scope, identify and elaborate on the key concepts found in the extant literature regarding the association between loneliness and well-being. The steps include (a) identifying the research topic, (b) finding relevant studies, (c) selecting a study, (d) synthesising and interpreting qualitative data and (e) synthesising and reporting the results. The sixth step ‘consultation exercise’ being an optional component of the scoping study framework (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005), will not be included in the present review. This approach will provide a context to address the current review’s queries. Subsequently, the search strategies will be detailed before presenting the results.

An evolutionary understanding of loneliness

For the purpose of this paper, loneliness is understood from an evolutionary perspective, as theorised by Cacioppo et al. (2006). This perspective posits that loneliness heightens survival mechanisms towards social threats to reduce the damages that can be inflicted from poor social interactions. Lonely individuals would subsequently be motivated to search for and maintain social connections to ensure survival and security. Experiencing loneliness over time can result in poor physiological and psychological health and its effects can be mitigated by interpersonal connections that function similarly to that of other basic human needs such as hunger and thirst. An experimental study by Poerio et al. (2016) reported that lonely individuals, who participated in daydreaming about socialising with a close other, showed a significant improvement in feelings of connectedness and belonging. The outcome indicates that the sense of belonging resulting from engaging in a pleasant social activity perhaps provides a rewarding, emotional benefit that alleviates feelings of loneliness.

Loneliness and well-being

In line with the emphasis on the evolutionary perspective of loneliness, an epidemiological cohort study by Matthews et al. (2019) found that loneliness is an indicator for poor functioning in the various domains of well-being. In particular, loneliness has been reported to have strong negative associations with subjective well-being (SWB) in both cross-sectional (e.g., Chen & Feeley, 2014; Haybron et al. 2008; Hsu, 2020) and longitudinal (e.g., Shankar et al., 2015; VanderWeele et al., 2012) studies. SWB is defined as people’s cognitive and emotional perceptions of their lives (Busseri & Sadava, 2011). It reflects a positive state that drives individuals to continue maintaining this state. Conversely, as described in the previous paragraph, loneliness is understood as an aversive state that acts as a signal to change behaviour. Hence, loneliness can affect SWB through the changes in emotions and moods. To illustrate, Hsu (2020) reported that among older adults the unfulfilled expectations from the family can result in feelings of loneliness and isolation, which in turn is resulted in depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction. Shankar et al. (2015) also noted that older individuals aged 50 years and above who experienced initial high levels of loneliness consistently have lower SWB over a six-year period. Similar outcomes are reported for young adults where evidence points to direct link between loneliness and low well-being (Fardghassemi & Joffe, 2021). These results confirm the notion that loneliness and SWB share a negative correlation. The perceptions of loneliness appear to influence an individual’s SWB despite the presence of factors that aim to promote SWB, suggesting that the aversive effects of loneliness may extend beyond negatively affecting one’s SWB to influence one’s overall life satisfaction due to the social disconnection from others since they perceive the people around them as a threat (Chernyak & Zayas, 2010).

Social relationships and loneliness

Pitman et al. (2018) underscored the importance of understanding how the quality and quantity of social relationships among young people affect the pathway between loneliness and well-being. A qualitative meta-analysis by Achterbergh et al. (2020) noted that the experience of loneliness in later stages of life is driven by relational and environmental factors faced in childhood and adolescence. Such factors include parent-child relationships and interactions with peers. The experience of loneliness varies across sociodemographic factors. Early experiences with poor parental bonds can lead to insecure attachments with external others such as friends. This is in accordance with the attachment theory, which posits that interactions with attachment figures (e.g., parents) build an infant’s mental representation of social relationships (Bowlby, 1973). These representations subsequently influence the infant’s behaviour, thought processes, and emotions throughout the lifespan. Additionally, parent-child relationships appear to be the most influential form of social bonds. Positive interactions with parents are necessary for individuals to effectively adapt to the various developmental periods. For example, Bostik and Everall (2007) reported that insecurely attached adolescents found difficulties forming emotionally close friendships as compared to their securely attached peers. This is in line with findings from Wiseman et al. (2006) which found that undergraduate students who felt that they lacked parental care and nurturance in their childhood had impaired self-concepts. This decreased their abilities to socialise effectively, which subsequently led to a dissatisfaction in interpersonal relationships and increased feelings of loneliness. Similarly, Karababa (2021) also noted that adolescents with more positive parental attachments have higher self-esteem, which in turn led them to perceiving themselves as less lonely. The abovementioned findings imply that the quality of early bonds with parents is essential to an individual’s development, which eventually influences life satisfaction.

In younger individuals, their lives revolve around forming social networks (Bostik & Everall, 2007; Crosnoe, 2000). These social networks can act as a buffer against any ill effects of stress (Rokach, 2016). Peer rejection and decreased social support has been found significantly associated with loneliness since it might make one feel disconnected with the social reality (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Rokach, 2016). At a stage when young individuals are expected to form fulfilling social bonds outside of their family, deficient peer relationships may make them vulnerable to physical and psychological health issues (Chango et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2013; Segrin & Passalacqua, 2010).

Thus, an individual’s early life experiences with social relations contribute to the experience of loneliness and well-being in later stages of life. The experience of loneliness can be minimised or exacerbated from the use of specific coping strategies. It is thus important for the mental health sector to understand what drives loneliness in young people, which prompted the current review. Keeping this as focus, the systematic scoping review was undertaken to examine the extent and range of research activity specifically focused on the experience of loneliness among young people and its subsequent effect on their well-being.

Methodology

Utilizing the widely endorsed six-step framework described by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), the researchers charted the below mentioned steps to identify relevant works to be included in the review. As mentioned in the earlier section, we followed five of the six steps in the framework, choosing not to include the sixth stage - ‘consultation exercise’, which is viewed as an optional component of the scoping study framework (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005).

Identifying the research question

Scoping reviews are undertaken to summarize what is known about a specific topic to date by maintaining a wide approach in order to generate breadth of coverage. (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Levac et al. 2009). Keeping in mind the objectives of this systematic scoping review we formed a broad research question which was: What is known from the extant literature about the experience of loneliness among youth and its subsequent effect on their well-being? Through this process we aimed to identify factors that could potentially influence loneliness in youth and we were also keen to know if those works focused on studying the effect of loneliness on well-being in youth.

Identifying relevant studies

Since scoping reviews are comprehensive, the search for the relevant works was done via multiple sources. To guarantee adequate and efficient coverage, specialized and interdisciplinary electronic databases utilized in this review were APA PsycINFO, Scopus, Emerald Insight and OneSearch (Bramer et al., 2017). Grey literature, which might not be well documented or easily obtainable (Adams et al., 2016), systematic and literature reviews and intervention studies were excluded. Additional searches included checking the reference lists of all included papers. We also carried out citation searches of key publications to identify subsequent publications.

Study selection

The team members independently searched for relevant works but the exploration of the available works yielded a large number of irrelevant studies. Discussions based on the initially reviewed articles were undertaken to draw conclusions and direct subsequent eligibility criteria. This criteria was refined as the review progressed and we learnt more about the existing body of works.

Eligibility criteria

This review utilised the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: in order to be included in the review, the paper had to report loneliness among youth, either as an independent variable (IV; variable that could be cause of a behaviour or an outcome), or as a dependent variable (DV; the outcome variable that depends on the IV). The review followed the definition of “youth” as individuals aged 15 to 24 years old [World Health Organisation (WHO), 2021]. Eligibility was limited to full-text, qualitative or quantitative research published within the last 10 years in a peer-reviewed English language journal. A 10-year time frame was used since boom in social technologies in the last decade have been documented to increase loneliness in modern society (Twenge et al., 2021). The ten year period would also ensure that the information extracted from the studies would have relevance in the current times (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Since many works on loneliness have already focused on older population (Fakoya et al., 2020) and there is a paucity of works examining the experience of loneliness among youth, the review focused on young people within the community. Papers utilising samples with pre-existing mental health issues were excluded as the researchers wanted to investigate loneliness and related factors within the general population. Though this review focused on youth, publications that included adult populations were retained if the results offered retrospective explanations on the risk factors of loneliness during the childhood or adolescence period (e.g., Stafford et al., 2016).

The review was conducted between 20 October 2020 and 30 March 2021. Based on the 10-year timeframe chosen as a criteria, initially papers published between 1 January 2011 and 28 February 2021 were included in the review. However, due to COVID-19, the research team was delayed in meeting time target for wrapping this paper. So another search for databases was done and the search date for related papers was extended to December 2021 to include more works. Search terms included Loneliness, Well-Being, Youth, Relationship, Social Support as keywords that were then combined using the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” to merge search terms. For instance Social Support AND lonel* AND well-being; Youth OR Students AND lonel* AND well-being and; Youth OR Adolescents AND Lone*; Relationship AND lonel* AND Youth. We screened titles and abstracts to determine whether the study met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Results

Data extraction and collection

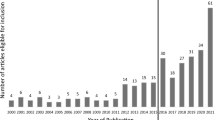

Database search yielded a total of 1260 papers. The journal articles were manually exported from the databases and imported into Rayyan QCRI (Ouzzani et al., 2016), a web-based application for database management of systematic reviews. After removing duplicates (n = 220) a total of 1040 records were left for screening.

Before starting the screening process, a benchmarking exercise was done to establish reliability with the blind function on. The reviewers first gave their decision on 10% of the papers and the first reviewer then turned the blind function off to reveal the decisions to the team. This allowed the team to see how many papers were unanimously agreed or disagreed upon. This initial phase of quality check when searching and selecting relevant studies is a crucial aspect of conducting a systematic review (Petrosino, 1995) since it ensures that expended time and effort is not wasted. It also standardizes the whole process and makes it more transparent and replicable (Belur et al., 2018). The benchmarking exercise showed 80% concurrence rate. The reviewers then discussed the reasons for their conflicting decisions. Following this, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were further refined and made more explicit and clearer. Once the benchmarking exercise was complete, reviewers proceeded with abstract screening. Application of the eligibility criteria identified 167 articles for full-text review. Any articles that were disagreed upon were re-read by both reviewers and discussed for relevance. Eventually, 20 papers were retained for the current review. The study selection process is summarised using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Chartering the data

The data from the selected articles were organised into a table in Microsoft Word, with the authors’ names arranged in alphabetical order (Table 1). The table columns comprised of author/year, country in which the research was conducted, sample demographics (age, gender), research aim, study design, measures, and relevant findings from the study.

Geographical location

The geographical range of the 20 studies included in this review was limited (Fig. 2). The studies took place in 13 out of the 195 countries listed by the Global Health Security Index (2020). Seven of the 20 studies were carried out in Europe and United Kingdom (Dalton & Cassidy, 2021; Inguglia et al., 2015; Kekkonen et al., 2020; Lyyra et al., 2021; Moksnes, et al., 2022; Phu & Gow, 2019; von Soest et al., 2020), while four studies were conducted in the United States of America (Lee & Goldstein, 2016; Newman & Sachs, 2020; Teneva & Lemay, 2020; Weisskirch, 2018). In Asia, a three studies were conducted in China (Kong & You, 2013; Tu & Zhang, 2015; Zhang et al., 2015), and one each in South Korea (Park & Lee, 2012), Pakistan (Yousaf et al., 2015) and Indonesia (Rahiem, et al., 2021). Two studies were carried out in Turkey (Arslan, 2021; Özdogan, 2021) while one study did not indicate the geographical location of participants.

Research designs and samples

Two major methodological patterns emerged in the included articles (Table 1- Appendix B). Firstly, majority (i.e., 14 of the 20 included studies) utilised a quantitative research design and two used a longitudinal approach (Kekkonen et al., 2020; von Soest et al., 2020). Two studies utilized qualitative approach (Janta et al., 2014; Rahiem, et al., 2021) and two made use of mixed-methods research design (Newman & Sachs, 2020; Teneva & Lemay, 2020).

Secondly, we found that 11 of the 20 studies recruited a mix of adolescent and young adult samples (Dalton & Cassidy, 2021; Inguglia et al., 2015; Kong & You, 2013; Lee & Goldstein, 2016; Moksnes et al., 2022; Özdogan, 2021; Park & Lee, 2012; Phu & Gow, 2019; von Soest et al., 2020; Weisskirch, 2018; Yousaf et al., 2015) while of the remaining nine studies, four focused on only adolescent samples (Arslan, 2021; Kekkonen et al., 2020; Lyyra et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2015), and remaining on university students. The sample sizes for the included works ranged from 166 to 5883 participants. All studies included both males and females in their samples.

Tools used to measure variables

The included studies in this systematic scoping review used self-report measures of loneliness and well-being via questionnaires, interviews, diaries, focus groups and online forum threads. Studies defined the concepts of loneliness and well-being in similar ways. Loneliness was generally characterised as an unpleasant experience from the lack of quality and/or quantity of social relations. Though the authors were in agreement on the definition of loneliness, different studies chose to focus on different aspects of loneliness. Such aspects included feelings of neglect or disparities between the past and expected social inclusion. Majority of the studies (n = 13) utilised the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale or one of its versions as a measure of loneliness.

Most studies defined well-being as a multidimensional concept which included notions such as self-esteem and life satisfaction. Rosenberg-Self-Esteem-Scale was the most commonly used tool (RSES; n = 4; Kong & You, 2013; Park & Lee, 2012; Teneva & Lemay, 2020; Weisskirch, 2018), followed by Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale ( long and short versions) (WEMWBS; n = 3; Dalton & Cassidy, 2021; Lyyra et al., 2021; Moksnes et al., 2022), 2013), Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; n = 2; Phu & Gow, 2019; Weisskirch, 2018) and Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; n = 2; Kong & You, 2013; Tu & Zhang, 2015).

Findings

This section consolidates themes that emerged from this review. Multiple factors such as parental bonding and relationships, personality, social support and stress emerged as significant contributors to experience of loneliness among youth, which in turn impacted their well-being.

Loneliness as multidimensional construct

Though most of the existing works (n = 16) approached loneliness as a unidimensional experience, a few studied loneliness as a multidimensional construct. Teneva & Lemay (2020) in their study examined the different impact of trait and state loneliness on self-esteem and affect. Their results showed that both trait and state loneliness could distort a person’s vision of future and lead them to expect and experience worse outcomes. von Soest et al. (2020) conceptualized loneliness as having social and emotional facets. While emotional loneliness increased across adolescents and young adulthood years, social facet of loneliness plateaued when individuals reached their mid-20 s. Özdogan (2021) examined emotional facet of loneliness further by breaking down into romantic and family loneliness. Their study found subjective well-being to be negatively correlated to romantic and family loneliness. Increase in social and emotional loneliness predicted meaninglessness of life.

Parental bond as a protective barrier against loneliness

Positive parental bonding was frequently reported as a protective barrier against loneliness among young people (Inguglia et al., 2015; von Soest et al., 2020; Weisskirch, 2018). Notably, these studies explicitly reported the strong influence of past memories of nurturing and loving parents on the individual’s current state of loneliness and well-being. von Soest et al. (2020) noted that perceived parental support predicted higher autonomy and relatedness in adolescents and young adults, which, in turn, predicted lower loneliness. Weisskirch (2018) too argued that young adults’ experience with parenting influenced their ability to achieve intimacy resulting in personal enhancement associated with well-being. Thus, close bonding with parents, albeit indirectly, in a way protected the young adults from negative psychological outcomes emerging out of loneliness. Young adults who perceived their parents as more supportive of their sense of relatedness reported higher levels of connectedness to others, which in turn negatively associated with loneliness (Inguglia et al., 2015). Their study highlighted the relevance of supportive parenting for psychological well-being in emerging adults.

Social support as an inhibitor of loneliness

Majority of the included studies gave evidence for the inhibiting effect of social support on loneliness ( Inguglia et al., 2015; Janta et al., 2014; Kekkonen et al., 2020; Kong & You, 2013; Lee & Goldstein, 2016; Park & Lee, 2012; Phu & Gow, 2019; von Soest et al., 2020; Yousaf et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). These studies frequently implied that social support from family and friends was effective in decreasing the experience of loneliness. According to Inguglia et al. (2015), a sense of relatedness to other people acted as a protection against feelings of loneliness. Social support was a significant mediator between interpersonal relationship and loneliness, specifically in the school setting (Zhang et al., 2015). Not having close friends in adolescence was related with higher experience of loneliness ( von Soest et al., 2020). According to them, this could influence the future social trajectory of these individuals, where they could potentially lack friends and support network during young adulthood stage. Presence of carings realtionships resulted in sense of worthiness in adolescents and youths and reduced their need to daydream as a way of coping with loneliness (Yousaf et al., 2015). Having more friends on Facebook resulted in lower levels of loneliness and higher subjective happiness (Phu & Gow, 2019). Bonding relation and social support were strongly and negatively related to the level of loneliness in college students (Park & Lee, 2012). This was similar to findings by Yousaf et al. (2015), Kong & You, (2013), and Janta et al. (2014), who too found that perception of social support was negatively correlated with loneliness among undergarduate students, with those low in social support experiencing more loneliness. Social support as a stress buffer against loneliness varied for different sources of support ( Lee & Goldstein, 2016). For college aged youth, only support from friends and romantic partners negatively associated with loneliness. Family support was not associated with loneliness. Quality of realtionship with teachers and same sex friends too reduced the experience of loneliness in adolescents ( Zhang et al., 2015).

Social media, loneliness and wellbeing

Of particular interest, social media was found to influence the pathway between loneliness and well-being. However, there were mixed findings regarding its influence. For example, Park and Lee's study (2012) found that the use of smartphones for supportive communication among university students improved social bonds and psychological well-being. Janta et al. (2014) found that online social interactions could act as a form of social support. They reported that doctoral students utilised online social platforms as a means of escape from their experience with loneliness in school. Also having friends on social networking sites acted as a buffer against loneliness. Phu and Gow (2019) found that having greater number of Facebook friends positively correlated to subjective happiness and negative correlated to loneliness. However, their study found no associations between loneliness and the time spent on Facebook among young adults. These findings have implications, especially in the present times, when COVID-19 driven changes to social interactions encourages us to use social networking sites more often as compared to pre COVID-19 days. Not all time spent on such sites is fruitful and contributing to our well-being. Outcomes from the review showed that Internet and social networking sites could both be tools to forge and nurture online relationships as well as lead to risky, impulsive, or excessive usage in lonely users. Fulfilling engaging relationships not only reduce loneliness but also can help control dysfunctional online behaviours like problematic or addictive internet usage that can result in social, emotional, physical, or functional impairment (Dalton & Cassidy, 2021).

Loneliness, well-being and mental health

Feeling lonely can have debilitating consequences for well-being and mental health. In adolescents, where on one hand sense of belongingness acts as a buffer against emotional and behavioral problems, loneliness has adverse impact on psychosocial development. Relationships play a significant role in our life and this is true for the youth as well. Loneliness has shown a strong effect on well-being, by increasing the absence of well-being and decreasing positive well-being. Arslan (2021) found that adolescents who had low levels of inclusion at school reported greater feelings of loneliness and mental health problems. In their study, loneliness also had a negative association with subjective well-being. Similarly, being lonely was associated with lower life satisfaction in young adults as well (Kekkonen et al., 2020; Kong & You, 2013; Tu & Zhang, 2015). Loneliness was negatively related to affective well-being (Newman & Sachs, 2020) and psychological well-being (Teneva & Lemay, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic isolation generated strong feelings of emotional distress among a sample of university undergraduates in Indonesia who reported confusion, anger, frustration and unceratinity about their future (Rahiem, et al., 2021). Loneliness was highlighted as a significant risk factor for mental wellbeing and self-esteem in Nordic adolescents as well (Lyyra et al., 2021). Reviewed works also showed that loneliness is associated with an increased risk of certain mental health problems, including depression and anxiety (Inguglia et al., 2015; Janta et al., 2014; Kekkonen et al., 2020; Moksnes et al., 2022; Park & Lee, 2012; Tu & Zhang, 2015; von Soest et al., 2020), increased stress (Inguglia et al., 2015; Lee & Goldstein, 2016), diminished self-esteem (Lyyra et al., 2021; Teneva & Lemay, 2020), and less positive affect (Newman & Sachs, 2020; Teneva & Lemay, 2020).

Discussion

The two questions that directed this systematic scoping review brought attention to the relationship between loneliness and well-being, and how this pathway is affected by certain key factors identified in the literature. In summary, this review of 20 articles reinforces understandings of the experience of loneliness as a complex, evolutionary process that is influenced by relational and environmental factors. It further suggests that there are strong similarities between the experience of loneliness in different parts of the world. Insights can be concluded from the current review about the experience of loneliness on well-being among young people.

The importance of relational support

It is noteworthy that the included studies reported a high number of loneliness-prevention processes at the relational level of young people. Acknowledging this fits with the argument that positive social resources, including friends and family, can play a crucial role in abating loneliness. In other words, the attempts by mental health practitioners to tackle the issue of loneliness among young people should consider the relational factors. To this end, loneliness interventions should not prioritise only relational processes over other resources (e.g., environmental), or vice versa. This could be tricky, given the fact that close relationships have been recognised as a protective factor (Chang et al., 2017; Kalaitzaki & Birtchnell, 2014; Segrin & Passalacqua, 2010). Nonetheless, tapping on the bidirectional nature of relationships, mental health practitioners could enhance the support given to young individuals and their social systems in learning ways of advancing loneliness-prevention exchanges.

It should be noted that although the relational resources were relatively similar across the included studies, applying this notion to specific contexts should be done with caution. To illustrate, significant ethnic differences were found in the relationship between parental bonding and loneliness (Weisskirch, 2018). This means that appreciation of intimacy between the parent and child may not resonate with all across cultures. The cultural orientations or ethnic differences may cause the child to prioritise other external relationships (e.g., friends) over parental relationship to deal with the loneliness. Thus, mental health practitioners should caution against the assumption that a specific relational resource is ubiquitously protective in all young people. Instead, they should target the protective relationship that is relevant to that particular young individual. In doing so, practitioners enhance collaboration between them and their clients in the therapeutic process, and increase their chance at success by exploring acceptable means of moderating the challenges that a specific context imposes on the individual.

Impact of loneliness on well-being and mental health of youth

This scoping review identified the adverse effect of loneliness on emotional health of young population. Loneliness resulted in not only poor mental health but also significantly lowered positive well-being among youth. Experiences of diminished life satisfaction, lower affective and psychological well-being, among lonely youth, thus necessitates more focused research on loneliness experiences among the young and adolescent populations. Reduced or limited access to friendship groups or peers have a psychological cost for youth as many participants in the included works showed symptoms of poor mental health including anxiety and depression. With world now emerging from the shadows of CoVID-19 pandemic, there is an urgent need to focus on the emotional well-being of the young population. The debilitating effects of loneliness among youths have to be acknowledged by the society in order to start conversations on this not-so-trivial issue.

Contributions of social media in current times

Apart from the importance of relational support for managing loneliness among youth, this review also identified the contributions of social media as a tool for social support. The fact that the loneliness of young people was intertwined with social media usage could be due to globalisation and boom in social technologies. The use of social networking sites was means of escape from reality (Janta et al., 2014) but this was also linked to a reinstated sense of happiness and belonging (Phu & Gow, 2019).

Despite the contributions of social media usage in decreasing loneliness, individuals may not reap equivalent benefits at par with face-to-face social support or interactions. Significantly, one study (i.e., Kekkonen et al., 2020) emphasised the importance of in-person social interactions. Kekkonen et al. (2020) noted that lower frequencies of physically meeting friends significantly decreased life satisfaction among young adults. These findings gain significance in light of the social distancing measures in place across many countries to prevent the spread of CoVID-19. In such circumstances, social media could offer a safe alternative and be a valuable platform for lonely individuals seeking social support and interactions. In present times when COVID-19 driven restrictions might force people to limit their face-to-face interactions, social media could be an effective tool to manage the consequences of loneliness.

What stood out in the review was limited works examining the experience of loneliness in youths. The body of reviewed works showed that the youth too are vulnerable to experiencing loneliness and suffer its consequences. Some parts of the world are still focused on fighting COVID -19 by imposing restrictions on social gatherings and limiting social contact if need be. Since youths thrive on social interactions and engagements, the impact of these restrictions on their emotional health might be more severe than other demographics within the society. Youth are our future and we need to now focus on their experience of loneliness. Studies focused on examining and understanding their experiences are required so that solutions can be offered to mitigate the effect of loneliness in order to ensure that this valuable demographic does not suffer silently.

Limitations

This review is not without limitations. Firstly, logistical constraints limited the ability to consult with relevant stakeholders (e.g., loneliness-focused practitioners). Given the vast research conducted on loneliness and well-being, as well as the dynamic nature of social media (Phu & Gow, 2019) and parent-child relationships (Lunkenheimer et al., 2017), this review will require an update. Ideally, it should be done with the consultation of relevant stakeholders. Secondly, the search for articles excluded non-English language journals. This creates the possibility that the current review could have reduced relevant insights on the topic of interest in other languages. Thirdly, the methodology did not focus on quality assessment of the included research papers. This is reflective of the scoping review approach (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Nonetheless, quality assessment should be considered in the future, especially if the findings from this review are going to help direct future interventions. Lastly, this review only focused on empirical works and did not include literature reviews, systematic reviews, interventions and grey literature. Due to not including all available data on this topic, a selection bias might have occurred. Since for this review only four databases were utilised, with searched articles limited to the last 10 years, these criteria may have limited the scope of findings.

Conclusion

There is a rising public health concern worldwide due to the social distancing measures that were brought in to mitigate the effect of COVID-19 pandemic. In this systematic scoping review, information was gathered to shed light on the current evidence related to the experience of loneliness in young people and how this affects their well-being. Essentially, their capacity to ameliorate loneliness is rooted in their early relationships with parents, their social support and the ways in which they choose to cope with the loneliness (e.g., using social media to connect with others). Understanding that these factors feature in empirical accounts of adolescents’ and young adults’ loneliness is vital to the mental healthcare sector’s efforts to tackle this problem. Emerging adulthood is an important transition period with focus on growth, gains, and planning for positive future. However, COVID-19-related stressors and disruptions led to social isolation, confinement, loss of freedom, and a sense of uncertainty that significantly impacted the mental health and psychosocial well-being of youth. This systematic scoping review did not find many works that focused on the experience of loneliness among youth in community. Studies that measure loneliness and well-being at different time points appear to be need of the hour. This will allow researchers to assess the temporal unfolding of loneliness at different intensities of the imposed social distancing measures. Studies need to be replicated and utilise more rigorous designs to validate the results from the included works in this review. By addressing these factors, researchers can help facilitate better mental health in the young population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Achterbergh, L., Pitman, A., Birken, M., Pearce, E., Sno, H., & Johnson, S. (2020). The experience of loneliness among young people with depression: A qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 415. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02818-3

Adams, J., Hillier-Brown, F. C., Moore, H. J., Lake, A. A., Araujo-Soares, V., White, M., & Summerbell, C. (2016). Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’and ‘grey information’in public health: Critical reflections on three case studies. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1–11.

Agarwal, D., Hanafi, N. S., Chippagiri, S., Brakema, E. A., Pinnock, H., Khoo, E. M., Sheikh, A., Liew, S.-M., Ng, C.-W., Isaac, R., Chinna, K., Ping, W. L., Hussein, N. B., Juvekar, S., Das, D., Paul, B., Campbell, H., Grant, E., Fletcher, M., … the, R. C. (2019). Systematic scoping review protocol of methodologies of chronic respiratory disease surveys in low/middle-income countries. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 29(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-019-0129-7

Alcaraz, K. I., Eddens, K. S., Blase, J. L., Diver, W. R., Patel, A. V., Teras, L. R., Stevens, V. L., Jacobs, E. J., & Gapstur, S. M. (2019). Social isolation and mortality in US black and white men and women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy231

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arslan, G. (2021). School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: Exploring the role of loneliness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 70–80.

Belur, J., Tompson, L., Thornton, A., & Simon, M. (2018). Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: Exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociological Methods & Research, 0049124118799372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799372

Bostik, K. E., & Everall, R. D. (2007). Healing from suicide: Adolescent perceptions of attachment relationships. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 35(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880601106815

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss (2nd edn., vol. 1). Basic Books. https://parentalalienationresearch.com/PDF/1969bowlby.pdf

Bramer, W. M., Rethlefsen, M. L., Kleijnen, J., & Franco, O. H. (2017). Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–12.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 290–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310391271

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. WW Norton & Company.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., & Spiegel, D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

Chang, E. C., Chang, O. D., Martos, T., Sallay, V., Lee, J., Stam, K. R., Batterbee, C.N.-H., & Yu, T. (2017). Family support as a moderator of the relationship between loneliness and suicide risk in college students: Having a supportive family matters! The Family Journal, 25(3), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480717711102

Chango, J. M., Allen, J. P., Szwedo, D., & Schad, M. M. (2015). Early adolescent peer foundations of late adolescent and young adult psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(4), 685–699.

Chen, Y., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407513488728

Chernyak, N., & Zayas, V. (2010). Being excluded by one means being excluded by all: Perceiving exclusion from inclusive others during one-person social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(3), 582–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.01.004

Cigna. (2018). Cigna U.S. loneliness index. https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/newsroom/loneliness-survey-2018-full-report.pdf

Cole, S. W., Capitanio, J. P., Chun, K., Arevalo, J. M. G., Ma, J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Myeloid differentiation architecture of leukocyte transcriptome dynamics in perceived social isolation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(49), 15142–15147. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1514249112

Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311

Crosnoe, R. (2000). Friendships in childhood and adolescence: The life course and new directions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695847

Dalton, F., & Cassidy, T. (2021). Problematic Internet usage, personality, loneliness, and psychological well-being in emerging adulthood. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 21(1), 509–519.

Fakoya, O. A., McCorry, N. K., & Donnelly, M. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–14.

Fardghassemi, S., & Joffe, H. (2021). Young adults’ experience of loneliness in London’s most deprived areas. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660791

Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: A lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Haybron, D. M., Hill, S. E., Buss, D. M., McMahon, D. M., Schimmack, U., Pavot, W., Lucas, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Kalil, A., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L., Thisted, R. A., Robinson, M. D., Compton, R. J., Fujita, F., Prizimic, Z., Oishi, S., Koo, M., … Larsen, R. J. (2008). The science of subjective well-being (pp. xiii–xiii). Guilford Press.

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psycholology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Hsu, H.-C. (2020). Typologies of loneliness, isolation and living alone are associated with psychological well-being among older adults in Taipei: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249181

Index, G. (2020). COVID-19: Identifying the most vulnerable countries using the GHS index and global flight data. https://www.ghsindex.org/news/covid-19-identifying-the-most-vulnerable-countries-using-the-ghs-index-and-global-flight-data/

Inguglia, C., Ingoglia, S., Liga, F., Lo Coco, A., & Lo Cricchio, M. G. (2015). Autonomy and relatedness in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Relationships with parental support and psychological distress. Journal of Adult Development, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9196-8

Janta, H., Lugosi, P., & Brown, L. (2014). Coping with loneliness: A netnographic study of doctoral students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(4), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.726972

Kalaitzaki, A. E., & Birtchnell, J. (2014). The impact of early parenting bonding on young adults’ internet addiction, through the mediation effects of negative relating to others and sadness. Addictive Behaviors, 39(3), 733–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.002

Karababa, A. (2021). Understanding the association between parental attachment and loneliness among adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01417-z

Kekkonen, V., Tolmunen, T., Kraav, S.-L., Hintikka, J., Kivimäki, P., Kaarre, O., & Laukkanen, E. (2020). Adolescents’ peer contacts promote life satisfaction in young adulthood — A connection mediated by the subjective experience of not being lonely. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110264

Kirzinger, A., Kearney, A., Hamel, L., & Brodle, M. (2020). KFF health tracking poll - Early April 2020: The impact of coronavirus on life in America. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/report/kff-health-tracking-poll-early-april-2020/

Kong, F., & You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6

Korzhina, Y., Hemberg, J., Nyman-Kurkiala, P., & Fagerström, L. (2022). Causes of involuntary loneliness among adolescents and young adults: An integrative review. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 27(1), 493–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2022.2150088

Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186

Lee, C.-Y.S., & Goldstein, S. E. (2016). Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: Does the source of support matter? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 568–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9

Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

Levac, D., Wishart, L., Missiuna, C., & Wright, V. (2009). The application of motor learning strategies within functionally based interventions for children with neuromotor conditions. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 21(4), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181beb09d

Lunkenheimer, E., Ram, N., Skowron, E. A., & Yin, P. (2017). Harsh parenting, child behavior problems, and the dynamic coupling of parents’ and children’s positive behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(6), 689–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000310

Lyyra, N., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Eriksson, C., Madsen, K. R., Tolvanen, A., Löfstedt, P., & Välimaa, R. (2021). The association between loneliness, mental well-being, and self-esteem among adolescents in four Nordic countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7405.

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Goldman-Mellor, S., Kepa, A., Moffitt, T. E., Odgers, C. L., & Arseneault, L. (2019). Lonely young adults in modern Britain: Findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 49(2), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718000788

Moksnes, U. K., Bjørnsen, H. N., Eilertsen, M.-E.B., & Espnes, G. A. (2022). The role of perceived loneliness and sociodemographic factors in association with subjective mental and physical health and well-being in Norwegian adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 50(4), 432–439.

Mollenkopf, D. A., Ozanne, L. K., & Stolze, H. J. (2020). A transformative supply chain response to COVID-19. Journal of Service Management, 32(2), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0143

Newman, D. B., & Sachs, M. E. (2020). The negative interactive effects of nostalgia and loneliness on affect in daily life. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2185. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02185

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Özdogan, A. Ç. (2021). Subjective well-being and social-emotional loneliness of university students: The mediating effect of the meaning of life. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(1), 18–30.

Park, N., & Lee, H. (2012). Social implications of smartphone use: Korean college students’ smartphone use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(9), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0580

Petrosino, A. J. (1995). Specifying inclusion criteria for a meta-analysis: Lessons and illustrations from a quantitative synthesis of crime reduction experiments. Evaluation Review, 19(3), 274–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841x9501900303

Phu, B., & Gow, A. J. (2019). Facebook use and its association with subjective happiness and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.020

Pitman, A., Mann, F., & Johnson, S. (2018). Advancing our understanding of loneliness and mental health problems in young people. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(12), 955–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30436-x

Poerio, G. L., Totterdell, P., Emerson, L. M., & Miles, E. (2016). Helping the heart grow fonder during absence: Daydreaming about significant others replenishes connectedness after induced loneliness. Cognition and Emotion, 30(6), 1197–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1049516

Rahiem, M. D., Krauss, S. E., & Ersing, R. (2021). Perceived consequences of extended social isolation on mental well-being: Narratives from Indonesian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10489.

Rokach, A. (Ed.). (2016). The correlates of loneliness. Bentham Science Publishers.

Segrin, C., & Passalacqua, S. A. (2010). Functions of loneliness, social support, health behaviors, and stress in association with poor health. Health Communication, 25(4), 312–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410231003773334

Shankar, A., Rafnsson, S. B., & Steptoe, A. (2015). Longitudinal associations between social connections and subjective wellbeing in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychology & Health, 30(6), 686–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.979823

Sport. (2020). Wellbeing and loneliness - Community life survey 2019/20. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-life-survey-201920-wellbeing-and-loneliness/wellbeing-and-loneliness-community-life-survey-201920#contents

Stafford, M., Kuh, D. L., Gale, C. R., Mishra, G., & Richards, M. (2016). Parent-child relationships and offspring’s positive mental wellbeing from adolescence to early older age. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1081971

Stocker, C. M., Gilligan, M., Klopack, E. T., Conger, K. J., Lanthier, R. P., Neppl, T. K., O’Neal, C. W., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2020). Sibling relationships in older adulthood: Links with loneliness and well-being. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000586

Teneva, N., & Lemay, E. P. (2020). Projecting loneliness into the past and future: implications for self-esteem and affect. Motivation and Emotion, 44(5), 772–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09842-6

Tu, Y., & Zhang, S. (2015). Loneliness and subjective well-being among Chinese undergraduates: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 124(3), 963–980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0809-1

Twenge, J. M., Haidt, J., Blake, A. B., McAllister, C., Lemon, H., & Le Roy, A. (2021). Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness. Journal of Adolescence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006

VanderWeele, T. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). On the reciprocal association between loneliness and subjective well-being. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176(9), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws173

von Soest, T., Luhmann, M., & Gerstorf, D. (2020). The development of loneliness through adolescence and young adulthood: Its nature, correlates, and midlife outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 56(10), 1919–1934. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001102

Weinberg, M., & Tomyn, A. (2015). Community survey of young Victorians’ resilience and mental wellbeing. Full report: Part A and part B. V. H. P. Foundation. https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/-/media/ResourceCentre/PublicationsandResources/Research/Youth-resilience_mental-wellbeing_Full-Report.pdf?la=en&hash=5D6C001F0B6BF33C246A967A9D13A6E5D5E22566

Weisskirch, R. (2018). Psychosocial Intimacy, relationships with parents, and well-being among emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(11), 3497–3505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1171-8

World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). Adolescent health in the South-East Asia Region. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health

Wiseman, H., Mayseless, O., & Sharabany, R. (2006). Why are they lonely? Perceived quality of early relationships with parents, attachment, personality predispositions and loneliness in first-year university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.015

Yousaf, A., Ghayas, S., & Akhtar, S. T. (2015). Daydreaming in relation with loneliness and perceived social support among university undergraduates. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 41, 306.

Zhang, B., Gao, Q., Fokkema, M., Alterman, V., & Liu, Q. (2015). Adolescent interpersonal relationships, social support and loneliness in high schools: Mediation effect and gender differences. Social Science Research, 53, 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.05.003

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Since this systematic scoping review utilized published works, ethics approval was not needed.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Binte Mohammad Adib, N.A., Sabharwal, J.K. Experience of loneliness on well-being among young individuals: A systematic scoping review. Curr Psychol 43, 1965–1985 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04445-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04445-z