Abstract

Youth civic engagement is usually framed positively by existing literature, which finds that it can benefit young people’s well-being. Despite that, the literature lacks summarized evidence of the effects of various forms of youth civic engagement on different dimensions of well-being (i.e., psychological, emotional, social, and mental health). This scoping review identified 35 studies on this topic. Results demonstrated that social engagement (e.g., volunteering) generally positively affected psychological and social well-being and mental health. In contrast, the effects of other forms of civic engagement (i.e., protest action, conventional and online engagement) on these dimensions were more heterogeneous. Mixed evidence was found for the effects of all forms of civic engagement on emotional well-being. The issue of possible opposite effects, i.e., from well-being dimensions to civic engagement, was also addressed. They were found mainly for emotional well-being, which usually predicted civic engagement but not vice versa. Overall, this scoping review stresses the importance of distinguishing between different forms of civic engagement and between different dimensions of well-being in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Young people’s involvement in civic activities (e.g., volunteering, online activism, political protest, or participation in traditional politics) is often framed positively regarding youth empowerment and their stronger voice in society (Shaw et al., 2014). Normative forms of civic engagement are also traditionally considered beneficial for society as they enable people to formulate and advance their individual and collective interests, deliberate between different worldviews, and challenge social injustice (e.g., Sherrod et al., 2010). While accepting this view, it can be argued that apart from its societal impact, experiences with civic engagement are also inherently linked with individuals’ psychosocial development (e.g., the development of identity, Crocetti et al., 2014). As such, these experiences can have both positive and negative consequences for individuals’ well-being (Lerner et al., 2014, 2015). Previous research suggests that well-being is affected by various forms of civic engagement (Fenn et al., 2022). However, robust evidence is missing concerning the effects of civic engagement on specific well-being dimensions (e.g., emotional, psychological, or social). Thus, it is not known whether the implications of civic engagement are the same for all dimensions of well-being or differ from dimension to dimension. To address this gap, the present scoping review investigates what the existing research tells us about the effects of various forms of civic engagement on different dimensions of well-being among youth.

Youth’s well-being represents a crucial topic for current research as the onset of most mental disorders occurs during adolescence and young adulthood (Patel et al., 2007), and approximately 14% of young individuals worldwide (aged 10 to 19) are affected by a mental disorder (World Health Organization, 2021). Generally speaking, well-being refers to the overall quality of life (Diener et al., 1999). From a psychological perspective, well-being is often considered a part of mental health and is defined through the dimensions of emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Emotional well-being reflects the presence of positive affect (e.g., joy, contentment) and the absence of negative affect (e.g., anxiety, stress, depressive symptoms, etc.) about one’s life and overall life satisfaction. Psychological well-being refers to a more private and personal evaluation of one’s functioning in terms of self-worth and personal growth (Keyes, 2002). Finally, social well-being refers to people’s appraisals of their circumstances and functioning in society, involving the dimensions of integration (the quality of relationships with others), acceptance (favorable or unfavorable views of others), contribution (the evaluation of one’s social value), actualization (the assessment of social progress), and coherence (perceived meaningfulness and predictability of society; Keyes, 1998). These three dimensions of well-being are typically captured in clinical measurements of mental health, such as the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) questionnaire (Lamers et al., 2011). In addition, some studies conceptualize well-being as the absence of specific mental health symptoms (e.g., depression or anxiety). As this conceptualization (emotional, psychological, social, and mental health symptoms) is widely used in literature, it can provide a valuable framework for examining the varying effects of civic engagement among the youth. This conceptualization will also be used to organize the present review.

Civic engagement can be defined as “individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern” (American Psychological Association, 2009, para. 2). The scope of these actions ranges from individual volunteering, involvement in civic organizations, online activism, to political protest (e.g., demonstrating), and traditional political participation (e.g., Youniss et al., 2002). Although civic engagement can take many forms, a general distinction can be made between activities aimed at helping others or the community (sometimes called social engagement) and influencing political institutions or processes. The latter form can be further divided into conventional engagement, focused on electoral processes (e.g., voting or membership in a political party), and protest activities done outside of conventional institutions (e.g., demonstrating or signing petitions; Barrett & Zani, 2015; van Deth, 2014).

The role of civic engagement in individual development is particularly pronounced in adolescence and young adulthood. Previous research has shown that these life periods are more open to the effects of civic socialization than any other period. Civic beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral patterns formed at this age tend to remain relatively stable in middle adulthood and later (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989; Vollenbergh et al., 2001). Furthermore, adolescence and young adulthood are typically characterized by several transitions (e.g., educational or professional) and a relative abundance of time resources (compared to later adult life in which childcare or career development might become more relevant). Thus, a specific window of opportunities is created for exploration and participation in the civic sphere (Arnett, 2006; Núñez & Flanagan, 2015). Indeed, despite the popular image of disinterested and passive youth, studies employing inclusive definitions of civic engagement (i.e., going beyond mere voting or participation in traditional politics) show that a considerable part of the younger generation is active in civic life, particularly at the local level (e.g., European Commission, 2018).

A general theoretical framework for the association between civic engagement and well-being is provided by the relational developmental systems (RDS) metatheory (Lerner et al., 2014). This metatheory represents an umbrella for theories describing the processes that govern or regulate exchanges between individuals and their environment. These processes are expected to be bidirectional and considered adaptive if they produce mutually beneficial outcomes, including increased well-being (Lerner et al., 2015). From the RDS perspective, civic engagement can be understood as a multiple exchange between an individual and the environment, facilitated by adequate resources and opportunities. For example, previous research has shown that individuals from low-income, immigrant, minority, or otherwise marginalized backgrounds are usually less engaged in civic activities than their counterparts (Flanagan & Levine, 2010; Levinson, 2010) and face greater political costs (e.g., stress) but also benefits (e.g., empowerment) in relation to politics (Oosterhoff et al., 2022). Thus, individual trajectories of civic engagement might differ, some producing adaptive outcomes and others not (Lerner et al., 2014).

The topic of the association between civic engagement and well-being is not novel, as shown in several existing review studies (Ballard & Ozer, 2016; Fenn et al., 2022; Maker Castro et al., 2022; Vestergren et al., 2017). These reviews generally support links between these constructs, although the associations are not always uniform. The evidence of these links also differs by the focus of the reviews, as some of them focus on unspecified (usually adult) populations (Vestergren et al., 2017), a broad definition of civic engagement (Ballard & Ozer, 2016), or the selection of only one form of civic engagement (i.e., protesting and activism; Vestergren et al., 2017). Maker Castro et al. (2022) focus on racial/ethnic marginalization, and civic engagement is represented as one dimension of critical consciousness (i.e., critical action). Fenn et al. (2022) expand this topic by focusing on young adults (18–25 years of age) and differentiating between different forms of civic engagement. The results of Fenn et al. (2022) show that the type of civic engagement matters, as different types of civic engagement (e.g., volunteering, activism, and electoral behavior) demonstrate different associations with well-being. Specifically, social engagement, involving volunteering or charity, seems to have a more unequivocal positive relation to well-being than other types of engagement (Fenn et al., 2022), which corresponds with previous findings on the positive effects of service learning on well-being (Berezowitz et al., 2016; Hart et al., 2014).

However, existing reviews typically approach well-being without differentiation and do not provide coherent evidence about the effects of civic engagement on various dimensions of well-being. This gap becomes critical, especially when considering potential mechanisms through which civic engagement influences young people’s well-being. Previous theorizing suggests two pathways, which can be loosely labeled as psychological and social. For instance, Wray-Lake et al. (2019) refer to two broad sets of processes: one involving the development of identity, meaning, purpose, skills, self-efficacy, and internal locus of control, and the other that involves strengthening social relationships, networks, and support. Similar psychosocial processes have been proposed by Flanagan and Bundick (2011), who assume that civic engagement can be psychologically rewarding as it boosts a sense of benevolence one feels from helping, the feeling of attachment and identification, and social benefits resulting from social relationships and networks. Putting aside the improvement of objective social conditions, a literature review by Ballard and Ozer (2016) suggests the roles of coping with stress, empowerment, a sense of purpose and identity, and social capital and connection to other people. In addition, social psychological research on political activism, nested in the social identity approach, has found that the experience of civic engagement can lead to psychological changes in one’s self-definition or empowerment and changes in intragroup processes (e.g., support and unity; Drury & Reicher, 2000; Vestergren et al., 2019). Taken together, existing evidence suggests that civic engagement affects the psychological and social dimensions of well-being. In contrast, potential effects on emotional well-being or specific mental health symptoms seem to be less substantiated (except for better coping with stress). This is why it might be useful to examine different dimensions of well-being separately.

Current Study

Overall, the existing literature does not provide a comprehensive overview of how civic engagement affects different dimensions of well-being among the youth. To address this gap, the main research question of this scoping review is as follows: What is known from the existing research about the effects of various forms of civic engagement on different types of well-being among the youth? The previous line of work, focusing on different forms of civic activities, is expanded by considering their effects on different dimensions of well-being. Thus, this review examines evidence on how civic engagement affects emotional, psychological, or social well-being and mental health symptoms among the youth. In other words, it asks whether the effects of civic engagement are similar or diverse for different dimensions of well-being. In line with previous literature, different types of civic activities represented in selected articles are also distinguished.

Methods

This work used a scoping review as a framework. Thus, it follows a structured process to identify and map available evidence in a given field (Munn et al., 2018). The scoping review is based on a broadly defined research question, focusing on summarizing research findings and identifying research gaps. It does not, for instance, address the issue of the effectiveness of particular interventions, nor does it provide any implications for clinical or policy decision-making, which is usually done by systematic reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Munn et al., 2018). More specifically, the search procedure was based on Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework for conducting scoping reviews consisting of five steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

The identification of relevant studies consisted of three steps: a literature search in online databasesFootnote 1, a reference search from previously found studies, and a search in an online tool to find relevant papers (Connected Papers, n.d.). The online tool was used for exploratory purposes to check whether some additional papers were missed in the previous steps. The selection of literature in all these steps was based on three inclusion criteria: (1) empirical research studies published in peer-reviewed journals; (2) samples consisted of adolescents or young adults (approximate age 15–30) or had at least specified and analyzed a subsample in this age range; (3) the focus was on association between civic engagement or political participation and well-being or mental health. There were no inclusion criteria regarding geographical location, research design, or the exact measurement of variables of interest. All retrieved articles were written in English.

First, a literature search was carried out in six online databases: Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, PubMed, and ProQuest Central. These six databases were chosen because they were considered plausible to include psychological and mental health studies. This initial search retrieved a total of 5644 articles. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to eliminate articles not meeting the inclusion criteria, and 66 studies were retrieved for further reading. A detailed reading of these studies was conducted, and 28 that properly addressed this review’s theme and research question were selected for the review. The main reasons for exclusion in this step were an irrelevant sample (either a general population with undifferentiated age or a focus only on older adults; e.g., Dwyer et al., 2019; MacDonnell et al., 2017) and duplicate results. This search and reading took from August 2023 to November 2023. As the next step, references in articles retrieved from the database search were searched through. Six more studies fitting the inclusion criteria were found by this step. To ensure that some thematically relevant studies were not missed in the previous search, an online tool to find relevant papers by using already retrieved articles as input was used. One article fitting the inclusion criteria was added this way. Both these steps took time in November 2023. In the end, 35 articles were included in the review. While most of the search was done by one reviewer (MM), two other reviewers (JŠ and DSJ) checked and consulted on the process and read all the retrieved articles. The search is detailed in Fig. 1.

Results

Study Characteristics

Retrieved articles were diverse in methodology and operationalization of independent and dependent variables. Most articles utilized a single study design (n = 30); the most represented were cross-sectional studies (n = 17), followed by longitudinal studies (n = 9). There were also some experimental (n = 2) and qualitative (n = 3) studies. Only four articles used a multiple studies design, usually combining a cross-sectional study with an experimental or longitudinal study.

Most studies were done on North American or Western European samples (n = 27), with several exceptions. Three studies were conducted on samples from Hong Kong, one from India, one from Malaysia, one from Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Rep., Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela), one from New Zealand, and one from Poland. Additionally, one study included American, Italian, and Iranian subsamples. Regarding ethnicity, most studies (n = 26) had unspecified samples or samples mainly containing (more than 80%) people from majority populations (depending on the country in which the study was conducted, but usually Whites). Six studies had more mixed samples, but still, around half of the respondents were from the majority populations. One study focused on an immigrant sample (from African, Asian, European, and South American countries of origin), one study focused on Black and Latinx students, and one study focused solely on Blacks. Finally, one study focused on a sample of LGBT + adolescents.

The articles’ most significant source of diversity was the type of civic engagement. The papers used different measures; some measured more than one type of engagement. Different types of civic engagement are usually clustered into broader categories, an approach also used in this review. Thus, activities from the selected papers were clustered into three major forms of civic engagement based on categorizations present in the existing literature (Barrett & Zani, 2015; van Deth, 2014). First is the protest action, which can be defined as an unconventional activity (i.e., outside the established political institutions) targeting social and political issues (such as protesting, signing a petition, or activism). Second is social engagement, representing socially oriented activities focused on problem-solving and helping others (including donations, volunteering, or community participation). The last is conventional engagement, representing voluntary activities in the sphere of established political institutions (e.g., electoral activities, donating money to a political party). This final form can also include voting, although voting is often studied separately. The most frequently represented were activities falling into the category of protest action (n = 17), followed by social engagement (n = 13). Fewer studies were interested in conventional engagement (n = 9); most of them focused specifically on voting (n = 5). Apart from these major categories, there were two cases where authors were interested in organizational membership and two cases where authors did not specify or distinguish different types of engagement. While some authors (Kim & Hoewe, 2020; Oser et al., 2013) argued for distinguishing between online and offline activities, only five articles explicitly focusing on online engagement were found.

Regarding well-being as a dependent variable, most articles fell into one of the four main categories (some of them focused on more than one type of well-being). Most represented was emotional well-being (sometimes called positive affect or life satisfaction; n = 14), followed by mental health (n = 11), psychological well-being (n = 10), and social well-being (n = 9). Four studies measured well-being as a composite of emotional, psychological, and social well-being, so they could not investigate whether civic engagement affected these dimensions of well-being differently. Additionally, there were three cases where the measurement of well-being did not fit into the mentioned categories.

Because the primary focus of this review is on the distinction between different types of well-being, the following text is structured by this outcome variable. Thus, the results are clustered into general (i.e., non-differentiated), psychological, social, and emotional well-being. Additionally, research operationalizing well-being as mental health symptoms is reported in a separate part. Few papers used well-being indicators that did not fit into the mentioned categories. Some articles are mentioned more than once since they consider multiple types of well-being. Table 1 shows detailed information on the included studies.

General Well-Being

Some studies focused on a composite of psychological, social, and emotional well-being, thus not making inferences about specific dimensions of well-being. These studies all measured well-being by the MHC-SF (Lamers et al., 2011). A study by Hayhurst et al. (2019) from New Zealand showed that social engagement (e.g., volunteering) positively affected well-being, whether it was a past engagement or an intention to become engaged in the future. Nicotera et al. (2015) corroborated this on American undergraduate students, referring to the well-being composite as flourishing, and found that community engagement was positively associated with it. Fenn et al. (2023) also supported the positive effect of social engagement on American non-college youth, showing that self-efficacy positively mediated the effect. However, another study on American undergraduate students (Fenn et al., 2021) showed no direct effect of social engagement (e.g., community engagement, volunteering), although its effect might have been entirely mediated by self-efficacy, as community engagement and volunteering were positively associated with self-efficacy, which, in turn, was positively associated with well-being. Overall, the most represented activities related to general well-being fell into the social engagement category and tended to positively affect well-being.

Regarding conventional engagement, Fenn et al. (2021) found that electoral activities (e.g., voting) positively affected well-being. These results were corroborated by Fenn et al. (2023), where the association was also positive. In both these cases, these effects were positively mediated by self-efficacy. This is similar to social engagement, as conventional engagement seems to also have a beneficial effect.

As for the other categories of civic engagement, the studies by Fenn et al. (2021, 2023) also explored protest action and found negative associations with well-being. Furthermore, Fenn et al. (2023) also found that this effect was negatively mediated by meaning in life. The authors were also interested in online engagement, which was also negatively associated with well-being (Fenn et al., 2023). Contrary to the previous forms of engagement, protest action and online engagement seemed to have rather detrimental effects. Generally, due to the combined measure of well-being, the possible different effects on specific well-being dimensions could not be examined based on the mentioned results.

Psychological Well-Being

Cross-sectional studies focusing on psychological well-being showed that it was positively affected by different forms of civic engagement, such as online collective action (online engagement; Foster, 2014, 2015, 2019), conventional activism (conventional engagement; Klar & Kasser, 2009), human rights activism (protest action; Montague & Eiroa-Orosa, 2017), and prosocial activities (social engagement; Chan & Mak, 2020). However, in a study by Klar and Kasser (2009) on American youth, protest action specified as high-risk activism (e.g., activities with a higher risk of arrest), was not associated with psychological well-being. This corroborates with the cross-sectional research of Costabile et al. (2021) on Italian adolescents, where authors tested the opposite direction of effects and found that psychological well-being was positively associated with activism (i.e., political action through nonviolent means) but negatively with radicalism (i.e., political action through violent means). Their results also showed that these associations were mediated by social disconnectedness and the perceived illegitimacy of the authorities (Costabile et al., 2021). The qualitative study of Montague and Eiroa-Orosa (2017) on adolescents from the United Kingdom identified that the beneficial effect of protest action stemmed mainly from being active (rather than passive) and belonging to a larger group represented by a political movement. Generally, results from these studies show rather beneficial effects of civic engagement.

Foster (2014, 2015) was interested in the role of intervening variables in the case of online engagement and found that, at least among undergraduate women from Canada, the effect of online collective action depended on the perceived pervasiveness of discrimination (sexism). The beneficial effects only occurred when the perceived pervasiveness was high, but the effect was detrimental when there was no perceived pervasiveness (Foster, 2014, 2015). Additionally, Foster (2015) showed that another form of online collective action (tweeting) positively affected psychological well-being. However, in her subsequent study on a similar Canadian sample, Foster (2019) found that online activism was beneficial only in interaction with gender identity, meaning that engagement benefits well-being only when a person has a strong social identity, which serves as a protective factor. Overall, it seems that the effect of online engagement is more mixed and dependent on other factors.

However, it should be kept in mind that the results mentioned above come from cross-sectional studies, and thus, it can be premature to infer causality from them automatically. A longitudinal study on college students from Hong Kong by Chan and Mak (2020) showed that social engagement did not predict psychological well-being. Another longitudinal study on Hong Kong youth by Chan et al. (2021) even showed that more avid and long-term engagement in social movement (which would fall into the protest action category) had a detrimental effect on psychological well-being. Contrary to the cross-sectional and experimental results above, longitudinal results do not support the beneficial effect of civic engagement.

Social Well-Being

Social well-being is mainly studied in relation to two forms of civic engagement: social engagement and protest action. Regarding social engagement, existing literature showed that helping activities such as volunteering, donating to charities, or organizing events have primarily beneficial effects on social well-being among the youth from Italy (Albanesi et al., 2007; Cicognani et al., 2008), Hong Kong (Chan & Mak, 2020), and various European countries (Pavlova & Lühr, 2023). This was also corroborated by Chan and Mak’s (2020) longitudinal study, in which social well-being was the only dimension positively affected by prosocial activities. Although not precisely social engagement, Albanesi et al. (2007) and Cicognani et al. (2015) showed that, among the Italian youth, membership in prosocial organizations, including charity or youth groups, was also beneficial in this matter. In sum, the positive effect of social engagement on social well-being can be considered robust, supported by both cross-sectional (Albanesi et al., 2007; Cicognani et al., 2008; Cicognani et al., 2015; Chan & Mak, 2020; Pavlova & Lühr, 2023) and longitudinal (Chan & Mak, 2020) research.

The evidence in the case of protest action is mixed. Sohi and Singh (2015) conducted a study on Indian Northeasterners residing in Delhi and found that being engaged in protest action had a positive effect on social well-being, attenuating the otherwise negative effects of perceived discrimination. However, Albanesi et al. (2007) showed that protest action was unrelated to social well-being among Italian adolescents. In contrast, the longitudinal study on Hong Kong youth by Chan et al. (2021) showed that avid protest action and online engagement had a detrimental effect. These contradictory results might point to the role of perceived costs and riskiness of protest action. Sohi and Singh (2015) investigated engagement due to an acute perception of discrimination, whereas Albanesi et al. (2007) explored general participation in various protest activities during the previous year. Chan et al. (2021) studied a more long-term engagement in a social movement with a potentially increased risk of burnout and, thus, deteriorated social well-being. Thus, the effects of protest action are more mixed, similar to the case of psychological well-being mentioned above.

Emotional Well-Being

Compared to psychological and social well-being, the effects on emotional well-being are much more inconclusive. Because emotional well-being represents current emotional experiences and thus is related to various affective states, studies that measured this dimension of well-being as positive affect, happiness, and satisfaction with life, which are known indicators of emotional well-being (Keyes, 2002), were also included. Klar and Kasser (2009) found that, among American youth, low-risk activism (corresponding with a conventional form of engagement) was positively linked to life satisfaction and positive affect. Weitz-Shapiro and Winters (2011) corroborated this on a sample from various Latin American countries. However, Lorenzini (2015) tested these associations among employed and unemployed Swiss youth and found that life satisfaction was negatively associated with contacting political institutions, but only among employed youth. These results can suggest that conventional engagement is rather beneficial for emotional well-being.

In the case of protest action, Becker et al. (2011) found that collective action was positively associated with positive affect among German youth. Also, Lafreniere et al. (2023) found that Black Lives Matter (BLM) activism (mixed protesting and online participation) among Black young adults living in Canada had a positive cross-sectional association with life satisfaction. This was also corroborated by Klar and Kasser’s (2009) results on high-risk activism (representing protest action). However, a longitudinal study by Chan et al. (2021) showed no effect on emotional well-being in a sample of Hong Kong youth. Lorenzini (2015) found that life satisfaction was positively associated with protest action only among unemployed Swiss youth, whereas there was no supported association among employed youth. In sum, only cross-sectional results support the beneficial effect of protest action.

Regarding other forms of civic engagement, some studies showed no relation between social engagement and emotional well-being among Hong Kong youth (Chan & Mak, 2020), Canadian youth (Fang et al., 2017), and Malaysian youth (Zaremohzzabieh et al., 2019). Foster (2015) found that even though online engagement led to decreased negative affect (sadness), it was unrelated to positive affect (happiness), at least among Canadian undergraduate women. In a similar Canadian sample, online engagement had a beneficial effect on life satisfaction if this engagement was perceived as active and not passive, and this effect was moderated by gender identity (Foster, 2019). Thus, it seems that other forms of civic engagement can have only limited beneficial effects.

Some studies also addressed the question of causality. Weitz-Shapiro and Winters (2011) used cross-sectional comparisons based on eligibility to vote to identify causal relations and found a positive association between voting and life satisfaction. However, their further analysis did not provide evidence that voting (conventional engagement) increased life satisfaction, but that satisfied people were more likely to vote. The longitudinal study of Fang et al. (2017) also supported this causal direction because, in their model, happiness predicted social engagement and fit the data better than the model with opposite causality or bidirectional effects. On the other hand, the longitudinal study of Lafreniere et al. (2023) supported the opposite direction, that protest action positively predicted life satisfaction. This effect might be explained by the fact that this study was conducted among Black young adults, thus representing a marginalized group experiencing discrimination and oppression. However, their study tested only for this particular direction and thus could not infer possible reciprocal effects. Overall, it seems that, in this case, the effects are reversed, as emotional well-being can be considered a predictor of civic engagement rather than an outcome.

Mental Health Symptoms

Some studies understood well-being as mental health, defined as the absence of depressive symptoms, psychosomatic symptoms, or anxiety. The most often studied indicator was depressive symptoms. Existing literature showed that different forms of civic engagement, such as social engagement among American youth (Ballard et al., 2019; Hope et al., 2018; Kim & Morgül, 2017; Wray-Lake et al., 2019), conventional engagement among American adolescents (Ballard et al., 2019; Wray-Lake et al., 2019), and online engagement among Canadian undergraduate women (Foster, 2014) led to a decrease in these symptoms and thus could be considered beneficial for mental health. On the other hand, Wray-Lake et al. (2019) supported conventional engagement (e.g., contributing money to a political party) as a positive predictor of depressive symptoms in a sample of American youth, but this was not true for voting, which was measured outside other conventional activities. Furthermore, online participation was associated with increased depressive symptoms among American LGBT adolescents, and this relationship was fully mediated by exposure to web-based discrimination (Tao & Fisher, 2023). Regarding protest action, Ballard et al. (2019) found no relation to depressive symptoms, while Hope et al. (2018) showed that these activities can mitigate the negative effects of racial/ethnic discrimination among Latinx students, thus having a beneficial effect. However, Hope et al. (2018) also showed that among Black students, the effect of protest action was the opposite, meaning that it could exacerbate the experiences of discrimination among these students. Schwartz et al. (2023) also showed mixed results on a sample of American college students. While protest action (i.e., climate activism) was overall not directly associated with depressive or anxiety symptoms, it had some buffering effect between climate change anxiety and depressive symptoms (Schwartz et al., 2023). In general, it seems that social engagement is the most beneficial, whereas other forms of civic engagement have rather mixed effects.

Regarding other indicators of mental health, existing literature showed that protest action can lead to an increase in anxiety (Hope et al., 2018) and risky health behavior (Ballard et al., 2019). Furthermore, Hope et al. (2018) showed that this effect is similar to the case of depressive symptoms, as it was evident only for Black students but not for Latinx students, meaning that the effect of protest action was not the same for all marginalized groups. Also, at least among LGBT adolescents, online engagement can be positively associated with anxiety symptoms (through mediation by exposure to web-based discrimination) and a higher risk of substance use (Tao & Fisher, 2023). Social engagement (Ballard et al., 2019; Nicotera et al., 2015) and voting (Ballard et al., 2019) reduced various risky health behaviors among American youth. On the other hand, from a person-centered approach where mental health was viewed as trajectories formed from mental distress and mental well-being, social engagement was not associated with any of these trajectories among Norwegian adolescents (Wiium et al., 2023). The authors interpreted these results in a way that social engagement could serve as a buffer against mental distress but did not necessarily lead to optimal mental health. Boehnke and Wong (2011) also found that German youths’ activism in a peace movement (representing protest action) helped to reduce one’s “microworries” (i.e., anxiety or emotional disturbance about objects close to the self), which was associated with a decrease in anxiety and psychosomatic symptoms, and an improvement of mental health and experienced happiness. The qualitative study of Conner et al. (2021) from the United States showed that protest action had both positive and negative effects on mental health and that the positive effect was more pronounced among White and low-income respondents. In contrast, respondents of color and queer respondents have a more pronounced negative effect (Conner et al., 2021). Authors identified social capital (e.g., relationships), sense of purpose, identity, belief in effective change, and self-care as factors mitigating the negative effect of protest action on one’s well-being. Supportive relationships were the most important factor for activists of color, whereas a sense of purpose and identity was important for queer activists (Conner et al., 2021). Another qualitative study done on young Canadian climate change activists by Vamvalis (2023) concluded that there could be a positive association between protest action and better well-being (i.e., lower environmental anxiety and mental health distress). Also, similarly to Conner et al. (2021), this study also identified a sense of purpose and being part of a larger collective as important factors that facilitate this positive association. Overall, the results are similar to depressive symptoms, as social engagement seems to have the most beneficial effect.

The main advantage of the existing literature in this area is that most studies were longitudinal (Ballard et al., 2019; Boehnke & Wong, 2011; Hope et al., 2018; Wiium et al., 2023; Wray-Lake et al., 2019), and thus more suitable for assessing causality. Causality was further tested by Wray-Lake et al. (2019), who found that the effect between social engagement and depressive symptoms was bidirectional, meaning that not only did social engagement predict decreases in depressive symptoms, but also these symptoms predicted decreases in all measured forms of civic engagement (i.e., social engagement and conventional engagement).

Other Measures of Well-Being

Apart from the well-established dimensions, some authors used alternative conceptualizations of well-being. In one of their studies on American college students, Klar and Kasser (2009) measured vitality as a proxy for one’s well-being. Defined as feeling energized, alert, and alive, this construct was higher for respondents who participated in activism related to a college cafeteria (social engagement), a local and personally relevant issue. Fong and To (2022) focused on a sense of meaningfulness in life among Hong Kong high school students and found its positive association with social engagement. Nicotera et al. (2015) understood college self-efficacy as a facet of well-being and found a positive association with social engagement among American undergraduate students. Finally, Alfieri et al. (2019) used self-esteem and knowledge of Italian culture and the Italian language to measure well-being among immigrant youth from various countries of origin living in Italy. Results showed that social engagement was positively associated with all three facets of well-being and that being a first-generation immigrant and having close relatives in the country of origin were associated with lower well-being. Overall, these results supported the above-mentioned findings that social engagement has a beneficial effect.

Discussion

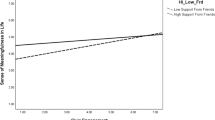

Civic engagement is an important part of youth’s psychosocial development, but little is known about how it can affect different facets of life’s quality. It has been known that different activities have various outcomes regarding well-being or mental health. This scoping review expands this topic by focusing on different dimensions of well-being to explore whether they are affected differently by civic engagement. Overall, the results have shown that the effect of civic engagement differs depending on the measured dimensions of well-being. Based on the results, the proposed directions of these effects are shown in Fig. 2.

How Civic Engagement Affects Well-Being

Results on psychological, social well-being, and mental health symptoms yielded similar results. Prosocial activities, such as volunteering or community engagement, usually positively affect these dimensions of well-being. The beneficial effects might stem from the fact that social engagement often has tangible local outcomes and often includes participation in groups. That is, there might be a beneficial effect of belonging and positive interpersonal relationships, thus improving the sense of belonging, social support, or positive social identity. Albanesi et al. (2007) and Cicognani et al. (2015) corroborated this, finding the positive effect of membership in prosocial groups on social well-being. In the case of psychological well-being, a possible explanation is that helping others or doing activities with a local impact helps to improve one’s self-worth and related self-perceptions. This was demonstrated in studies by Fenn et al. (2021, 2023), where self-efficacy mediated the effect of social engagement. In general, social engagement seems to have multiple benefits for youth political socialization.

In contrast, the consequences of protest action seem to be more mixed. These activities usually have beneficial effects when they focus on more personal matters (e.g., fighting experienced discrimination; Sohi & Singh, 2015) or are associated with one’s identity (e.g., gender or group identity; Foster, 2019). The association between protest action and ingroup identification is well-documented (Ayanian et al., 2021), as protest action can be seen as a form of intergroup behavior (Drury & Reicher, 1999; 2000). Some scholars even argue that strong ingroup identification can decrease subjective evaluation of risk associated with protest action, leading to an increase in the likelihood of participating in these activities (Uysal et al., 2022). It can be argued that being part of a larger group or collective is a protective factor because of the particular intragroup processes responsible for various individual psychological changes (Vestergren et al., 2018, 2019). However, these beneficial effects seem limited or even reversed when the protest action is too risky, intensive, violent, or long-term (e.g., Costabile et al., 2021). To be more precise, it is instead the individual evaluations of these factors that are instrumental, as it is known that it is the subjective evaluation, not expectation, of risks associated with protest action that predicts this behavior (Uysal et al., 2022). Overall, it is likely that when personally meaningful internal motivations for civic engagement are missing or unclear, active young people face a greater risk of phenomena such as overload and burnout.

A different pattern was found for emotional well-being. Conventional engagement and protest action are often cross-sectionally associated with this dimension of well-being (e.g., Klar & Kasser, 2009). However, longitudinal results do not provide uniform evidence for civic engagement to predict emotional well-being (Fang et al., 2017). Thus, although civic engagement can improve some aspects of one’s well-being (e.g., self-worth or sense of belonging), it would be exaggerated to conclude that it increases overall happiness or life satisfaction. This is an important caveat suggesting that civic engagement is not a panacea. Numerous factors affect youth well-being, and civic engagement is only one. The present results highlight the importance of differentiating between various dimensions of well-being. While psychological and social well-being might represent the outcomes of some forms of civic engagement, emotional well-being might instead serve as its predictor (e.g., Fang et al., 2017; Lorenzini, 2015). Instead of seeking universal effects, further research should look for the impact of civic engagement forms on specific aspects of well-being.

At the same time, there might be a difference between voting and other conventional activities (e.g., sending a letter to a public official). While both were positively associated with emotional well-being and better mental health (Ballard et al., 2019; Weitz-Shapiro & Winters, 2011), other conventional activities were also positively related to psychological well-being (Klar & Kasser, 2009). As voting represents a relatively low-cost form of engagement that does not require special skills and is supported by society, it does not necessarily increase one’s psychological well-being. Other conventional activities are also socially supported but require additional effort, so their effect on well-being might be similar to social engagement.

Online engagement yielded more mixed results, as it can have a positive impact (e.g., Foster, 2014, 2015, 2019), which can turn detrimental when engaged people face web-based discrimination (Tao & Fisher, 2023). Online activities often have similarities with protest action (e.g., online protesting) but are less risky, intensive, or costly. Results point out that the beneficial effects might be similar to protest action, but these effects can diminish for marginalized groups as they face more risks. Online engagement can be perceived as relatively safe, but this safeness does not necessarily correspond with the actual online experience (e.g., experiencing cyberhate). This would suggest that online participation does not serve as a protective factor against web-based discrimination, but these conclusions require further research.

Developmental Issues

Most studies employ samples consisting of both adolescents and young adults without making any inferences about differences between these two age groups. Studies conducted on specific adolescent or young adult samples are more limited, and their results do not provide robust developmental conclusions. That said, two trends seem apparent when comparing these articles, although both should be taken as cautious hypotheses. First, the beneficial effect of social engagement on well-being can be considered universal among the youth in general (e.g., Albanesi et al., 2007; Fong & To, 2022). Second, although the impact of protest action is generally mixed, the potential positive effect is more pronounced among adolescents than young adults (e.g., Montague & Eiroa-Orosa, 2017; Vamvalis, 2023). Overall, it can be assumed that, at least for some forms of civic engagement, there are age differences in the impact of being active. Still, this conclusion needs to be corroborated by future research.

Marginalized Groups

Existing research usually uses unspecified or mixed samples with no regard to the issue of marginalized groups. Some studies have shown that civic engagement, most notably protest action, can possibly attenuate the negative effect of discrimination on well-being (e.g., Lafreniere et al., 2023; Sohi & Singh, 2015). However, this is not uniform, as civic engagement can also worsen the psychological consequences of discrimination (Conner et al., 2021; Hope et al., 2018; Tao & Fisher, 2023). Some authors (Conner et al., 2021; Hope et al., 2018) conclude that different experiences of marginalized groups (e.g., experiences of discrimination) can be a conditioning factor for the differences in civic engagement outcomes. Thus, they are stressing the issue of differentiating marginalized groups. This was pronounced in the study of Hope et al. (2018), where the outcomes of protest action differed among Black and Latinx students, suggesting that the specific experiences of members of particular marginalized groups shape the role of civic engagement in the context of well-being.

Gaps in Existing Literature

The most common limitation in selected literature is the use of cross-sectional studies, which is a limitation that has been addressed by some previous reviews about civic engagement and well-being (Fenn et al., 2022; Vestergren et al., 2017). As this scoping review is interested mainly in how civic participation affects well-being, the issue of causality is crucial. Unfortunately, it cannot be sufficiently addressed in cross-sectional designs. Although results from cross-sectional studies are usually consistent with results from longitudinal research, the association between civic engagement and well-being can sometimes be in the opposite direction or bidirectional (Wray-Lake, 2019). Longitudinal studies on emotional well-being mainly show that higher emotional well-being leads to greater civic engagement but not vice versa (Fang et al., 2017). This was supported mainly for conventional engagement (Weitz-Shapiro & Winters, 2011; Wray-Lake et al., 2019), meaning that more satisfied and healthy people are likelier to vote. Studies on psychological and social well-being suggest that these dimensions are affected by civic engagement, but the issue of causality is explicitly addressed only in a few of them. These proposed directions are mentioned in the Fig. 2 above. Overall, more extensive longitudinal or experimental research is needed to provide more robust inferences about causality.

Also, even though adolescents and young adults can be considered a commonly targeted population, there is a lack of research exploring possible developmental changes in the impact of civic engagement on well-being. From the existing theory (Lerner et al., 2014, 2015), it could be assumed that the outcomes of civic engagement are instrumental in shaping patterns of political behavior. Also, there may be different factors for different age groups that determine whether a given civic activity will be beneficial or not. For example, adolescents could evaluate possible costs of risk associated with engagement differently than young adults because they usually live in different life situations (e.g., more free time or fewer responsibilities). Thus, the lack of developmental inferences in this field of study is an important gap that should be addressed by future studies.

Furthermore, most studies were conducted in North American or Western European contexts and thus with limited generalizability into other cultural contexts. The most represented forms of civic engagement in other contexts (mainly South and East Asia) were protest action (e.g., Chan et al., 2021) and social engagement (e.g., Fong & To, 2022). Both forms have mainly positive associations with social well-being and mixed effects with other dimensions of well-being, implying similar effects and interpretations as in North American or Western European contexts. However, conventional engagement, online engagement, and mental health were usually not included in studies from these cultural contexts.

Another important issue concerns how well-being and civic engagement are conceptualized and measured in the studies. The results emphasize the need to distinguish between different dimensions of well-being because civic engagement affects them differently. Most studies included in the review did not investigate all mentioned dimensions, and some studies used the composite of these dimensions as their dependent variable (e.g., Hayhurst et al., 2019; Nicotera et al., 2015), making it difficult to understand the interplay between civic engagement and well-being. Similarly, not differentiating between different forms of civic engagement (e.g., combining protesting with volunteering) might obscure their actual effects on well-being and lead to biased findings. This is also true for online civic engagement, often combined with its offline counterparts but can have different outcomes.

Finally, little is known about the psychological processes mediating the effects of civic engagement on well-being (cf. Hart et al., 2014). Existing reviews focusing on this topic acknowledge that a more precise investigation of social and psychological processes mediating the consequences of different types of civic engagement is needed (Ballard & Ozer, 2016; Hart et al., 2014; Vestergren et al., 2017). This investigation could help us understand why different forms of civic engagement vary in their effects on well-being.

Limitations

First, the selection of articles in this scoping review is limited by the used search terms and databases. Although additional search strategies were implemented (i.e., using references from selected articles and the online tool) to overcome this limitation, there might still be research not included in this review. Furthermore, search terms did not include additional constructs related to civic engagement or well-being (e.g., critical consciousness). Future reviews or research should focus on exploring the roles of these constructs that have mediating or moderating effects in the association between civic engagement and well-being.

Next, the terms youth or young people are characterized by a certain ambiguity. Although using samples from a specific age range was one of the inclusion criteria of this review, studies that partially exceeded the upper limit were included as they were still considered relevant for the review, and the exceeding was not considered substantial. Moreover, many studies used pooled samples of both adolescents and young adults, hindering the possibility of making more nuanced inferences about these two life periods. Future research can focus more on differentiating between different periods of life to explore the developmental trajectories in more depth. Furthermore, distinguishing between groups or identities (e.g., different marginalized groups) could provide insights into how different group experiences shape the role of civic engagement.

Conclusion

Existing literature provides only limited coherent knowledge about the impact of various forms of civic engagement on different well-being dimensions among the youth. This gap was addressed by this study by employing the scoping review framework. Results show that engaging in prosocial civic activities, such as volunteering, charity, or community engagement, can improve the psychological and social dimensions of young people’s well-being. Other forms of civic engagement can still fulfill this role, but their effects seem more uncertain and contingent on other factors. Conversely, emotional well-being seems to be rather a predictor than an outcome of civic engagement, as happier or more satisfied youth are more likely to be active. This points to the importance of distinguishing between different dimensions of well-being and not analyzing them as a composite. The same caution applies to distinguishing between various forms of civic engagement.

Notes

used keywords: (((political OR civic OR citizen OR public) NEAR/1 (engagement OR involvement OR participation OR action)) OR activism OR “collective action” OR protest OR voting) AND (well-being OR health OR happiness OR “life satisfaction” OR meaningfulness OR “positive affect”) AND (“young adults” OR adolescents OR adolescence OR youth OR “emerging adulthood” OR “young adulthood” OR “emerging adults”).

References

Albanesi, C., Cicognani, E., & Zani, B. (2007). Sense of community, civic engagement and social well-being in Italian adolescents. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 17(5), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.903.

Alfieri, S., Marzana, D., & Cipresso, P. (2019). Immigrants’ community engagement and well-being. Testing Psychometrics Methodology in Applied Psychology, 26, 601–619. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM26.4.8.

American Psychological Association (2009). Civic engagement. Retrieved January 3, 2023, from https://www.apa.org/education/undergrad/civic-engagement.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In J. J. Arnett, & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 3–19). American Psychological Association.

Ayanian, A. H., Tausch, N., Acar, Y. G., Chayinska, M., Cheung, W. Y., & Lukyanova, Y. (2021). Resistance in repressive contexts: A comprehensive test of psychological predictors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 912–939. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000285.

Ballard, P. J., Hoyt, L. T., & Pachucki, M. C. (2019). Impacts of adolescent and young adult civic engagement on health and socioeconomic status in adulthood. Child Development, 90(4), 1138–1154. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12998.

Ballard, P. J., & Ozer, E. J. (2016). Implications of youth activism for health and well-being. In J. Conner, & S. M. Rosen (Eds.), Contemporary Youth activism: Advancing Social Justice in the United States (pp. 223–243). Praeger.

Barrett, M., & Zani, B. (2015). Political and civic engagement: Theoretical understandings, evidence and policies. In M. Barrett, & B. Zani (Eds.), Political and civic engagement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 3–26). Routledge.

Becker, J. C., Tausch, N., & Wagner, U. (2011). Emotional consequences of collective action participation: Differentiating self-directed and outgroup-sirected emotions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(12), 1587–1598.

Berezowitz, C., Pykett, A., Faust, V., & Flanagan, C. (2016). Well-being and Student Civic outcomes. In J. A. Hatcher, R. G. Bringle, & T. W. Hahn (Eds.), Research on Student Civic outcomes in Service Learning (pp. 155–176). Routledge.

Boehnke, K., & Wong, B. (2011). Adolescent political activism and long-term happiness: A 21-Year longitudinal study on the development of micro- and macrosocial worries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(3), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210397553.

Chan, R. C. H., & Mak, W. W. S. (2020). Empowerment for civic engagement and well-being in emerging adulthood: Evidence from cross-regional and cross-lagged analyses. Social Science & Medicine, 244, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112703.

Chan, R. C. H., Mak, W. W. S., Chan, W. Y., & Lin, W. Y. (2021). Effects of social movement participation on political efficacy and wellbeing: A longitudinal study of civically engaged youth. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 1981–2001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00303-y.

Cicognani, E., Mazzoni, D., Albanesi, C., & Zani, B. (2015). Sense of community and empowerment among young people: Understanding pathways from civic participation to social well-being. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9481-y.

Cicognani, E., Pirini, C., Keyes, C., Joshanloo, M., Rostami, R., & Nosratabadi, M. (2008). Social participation, sense of community and social well being: A study on American, Italian and Iranian university students. Social Indicators Research, 89, 97–112.

Connected Papers. (n.d.). Connected Papers | Find and explore academic papers. Retrieved February 6, (2024). from https://www.connectedpapers.com/.

Conner, J. O., Crawford, E., & Galioto, M. (2021). The mental health effects of student activism: Persisting despite psychological costs. Journal of Adolescent Research, 38(1), 1–30.

Costabile, A., Musso, P., Iannello, N. M., Servidio, R., Bartolo, M. G., Palermiti, A. L., & Scardigno, R. (2021). Adolescent Psychological Well-being, Radicalism, and activism. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12590.

Crocetti, E., Erentaitė, R., & Zukauskienė, R. (2014). Identity styles, positive youth development, and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1818–1828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0100-4.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276.

Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (1999). The intergroup dynamics of collective empowerment: Substantiating the social identity model of crowd behavior. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 2(4), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430299024005.

Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2000). Collective action and psychological change: The emergence of new social identities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(4), 579–604. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466600164642.

Dwyer, P. C., Chang, Y. P., Hannay, J., & Algoe, S. B. (2019). When does activism benefit well-being? Evidence from a longitudinal study of Clinton voters in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Plos One, 14(9), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221754.

European Commission (2018). Flash Eurobarometer 455 -September 2017 European Youth Report (Report No. NC-06-17-423-EN-N). https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/82294.

Fang, S., Galambos, N. L., Johnson, M. D., & Krahn, H. J. (2017). Happiness is the way: Paths to civic engagement between young adulthood and midlife. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025417711056.

Fenn, N., Robbins, M. L., Harlow, L., & Pearson-Merkowitz, S. (2021). Civic engagement and well-being: Examining a mediational model across gender. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(7), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211001242.

Fenn, N., Sacco, A., Monahan, K., Robbins, M., & Pearson-Merkowitz, S. (2022). Examining the relationship between civic engagement and mental health in young adults: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2156779.

Fenn, N., Yang, M., Pearson-Merkowitz, S., & Robbins, M. (2023). Civic engagement and well-being among noncollege young adults: Investigating a mediation model. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(7), 2667–2685. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.23033.

Flanagan, C., & Bundick, M. (2011). Civic engagement and psychosocial well-being in college students. Liberal Education, 97(2), 20–27. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/civic-engagement-psychosocial-well-being-college/docview/1081182763/se-2.

Flanagan, C., & Levine, P. (2010). Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children, 20(1), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0043.

Fong, C-P., & To, S. (2022). Civic engagement, social support, and sense of meaningfulness in life of adolescents living in Hong Kong: Implications for social work practice. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal.

Foster, M. D. (2014). The relationship between collective action and well-being and its moderators: Pervasiveness of discrimination and dimensions of action. Sex Roles, 70, 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0352-1.

Foster, M. D. (2015). Tweeting about sexism: The well-being benefits of a social media collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54, 629–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12101.

Foster, M. D. (2019). Use it or lose it: How online activism moderates the protective properties of gender identity for well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.044.

Hart, D., Matsuba, K., & Atkins, R. (2014). Civic engagement and child and adolescent well-being. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective (pp. 957–975). Springer.

Hayhurst, J. G., Hunter, J. A., & Ruffman, T. (2019). Encouraging flourishing following tragedy: The role of civic engagement in well-being and resilience. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 48(1), 75–83.

Hope, E. C., Velez, G., Offidani-Bertrand, C., Keels, M., & Durkee, M. I. (2018). Political activism and mental health among Black and Latinx college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(1), 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000144.

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quaterly, 61(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787065.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197.

Kim, B., & Hoewe, J. (2020). Developing contemporary factors of political participation. The Social Science Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1782641

Kim, J., & Morgül, K. (2017). Long-term consequences of youth volunteering: Voluntary versus involuntary service. Social Science Research, 67, 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.05.002.

Klar, M., & Kasser, T. (2009). Some benefits of being an activist: Measuring activism and its role in psychological well-being. Political Psychology, 30(5), 755–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00724.x.

Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1989). Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(3), 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.416.

Lafreniere, B., Audet, É. C., Kachanoff, F., Christophe, N. K., Holding, A. C., Janusauskas, L., & Koestner, R. (2023). Gender differences in perceived racism threat and activism during the black lives Matter social justice movement for black young adults. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(7), 2741–2757. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.23043.

Lamers, S. M. A., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., ten Klooster, P. M., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2011). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20741.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Bowers, E. P., & Geldhof, G. J. (2015). Positive youth development and relational-developmental-systems. In W. F. Overton, P. C. M. Molenaar, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Theory and method (pp. 607–651). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lerner, R. M., Wang, J., Champine, R. B., Warren, D. J., & Erickson, K. (2014). Development of civic engagement: Theoretical and methodological issues. International Journal of Developmental Science, 8(3–4), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-14130.

Levinson, M. (2010). The Civic empowerment gap: Defining the Problem and locating solutions. In L. R. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C. A. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth (pp. 331–361). John Wiley.

Lorenzini, J. (2015). Subjective well-being and political participation: A comparison of Unemployed and Employed Youth. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9514-7.

MacDonnell, J. A., Dastjerdi, M., Khanlou, N., Bokore, N., & Tharao, W. (2017). Activism as a feature of mental health and wellbeing for racialized immigrant women in a Canadian context. Health Care for Women International, 38(2), 187–204.

Maker Castro, E., Wray-Lake, L., & Cohen, A. K. (2022). Critical consciousness and wellbeing in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 7(4), 499–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00188-3.

Montague, A. C., & Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. (2017). In it together: Exploring how belonging to a youth activist group enhances well-being. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1), 23–43.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Núñez, J., & Flanagan, C. (2015). Political beliefs and civic engagement in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of emerging Adulthood (pp. 481–498). Oxford University Press.

Nicotera, N., Brewer, S., & Veeh, C. (2015). Civic activity and well-being among first-year college students. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 3(1).

Oosterhoff, B., Poppler, A., Hill, R. M., Fitzgerald, H., & Shook, N. J. (2022). Understanding the costs and benefits of politics among adolescents within a sociocultural context. Infant and Child Development, 31(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2280.

Oser, J., Hooghe, M., & Marien, S. (2013). Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification. Political Research Quarterly, 66(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912436695

Patel, V., Fischer, A. J., Hetrick, S., & McGorry, P. (2007). Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. The Lancet, 369(9569), 1302–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7.

Pavlova, M. K., & Lühr, M. (2023). Volunteering and political participation are differentially associated with eudaimonic and social well-being across age groups and European countries. PLOS ONE, 18(2), 1–36.

Schwartz, S. E. O., Benoit, L., Clayton, S., Parnes, M. K. F., Swenson, L., & Lowe, S. R. (2023). Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Current Psychology, 42(20), 16708–16721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02735-6.

Shaw, A., Brady, B., McGrath, B., Brennan, M. A., & Dolan, P. (2014). Understanding youth civic engagement: Debates, discourses, and lessons from practice. Community Development, 45(4), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2014.931447.

Sherrod, L. R., Torney-Purta, J., & Flanagan, C. A. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth. John Wiley.

Sohi, K. K., & Singh, P. (2015). Collective action in response to microaggression: Implications for social well-being. Race and Social Problems, 7, 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-015-9156-3.

Tao, Y., & Fisher, C. (2023). Associations among web-based civic engagement and discrimination, web-based social support, and mental health and substance use risk among LGBT youth: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2196/46604.

Uysal, M. S., Acar, Y. G., Sabucedo, J. M., & Cakal, H. (2022). To participate or not participate, that’s the question’: The role of moral obligation and different risk perceptions on collective action. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 10(2), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.7207.

Vamvalis, M. (2023). We’re fighting for our lives: Centering affective, collective and systemic approaches to climate justice education as a youth mental health imperative. Research in Education, 117(1), 88–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/00345237231160090.

van Deth, J. W. (2014). A conceptual map of political participation. Acta Politica, 49(3), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.6.

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Chiriac, E. H. (2017). The biographical consequences of protest and activism: A systematic review and a new typology: A systematic review and a new typology. Social Movement Studies, 16(2), 203–221.

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Chiriac, E. H. (2018). How collective action produces psychological change and how that change endures over time: A case study of an environmental campaign. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(4), 855–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12270.

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2019). How participation in collective Action Changes relationships, behaviours, and beliefs: An interview study of the role of Inter- and intragroup processes. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 7(1), 76–99. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v7i1.903.

Vollenbergh, W. A. M., Iedema, J., & Raaijmakers, Q. A. W. (2001). Intergenerational transmission and the formation of cultural orientations in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 1185–1198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01185.x.

Weitz-Shapiro, R., & Winters, M. S. (2011). The link between voting and life satisfaction in Latin America. Latin American Politics and Society, 53(4), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2011.00135.x.

Wiium, N., Kristensen, S. M., Årdal, E., Bøe, T., Gaspar de Matos, M., Karhina, K., Larsen, T. M. B., Urke, H. B., & Wold, B. (2023). Civic engagement and mental health trajectories in Norwegian youth. Front Public Health, 11, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1214141.

World Health Organization (2021, November 17). Mental health of adolescents. Retrieved February 26, 2024 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

Wray-Lake, L., Shubert, J., Lin, L., & Starr, L. R. (2019). Examining associations between civic engagement and depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood in a national U.S. sample. Applied Developmental Science, 23(2), 119–131.

Youniss, J., Bales, S., Christmas-Best, V., Diversi, M., McLaughlin, M., & Silbereisen, R. (2002). Youth Civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(1), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00027.

Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Samah, A. A., Samah, B. A., & Shaffril, H. A. M. (2019). Determinants of happiness among youth in Malaysia. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 5(4), 352–370. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHD.2019.104370.

Funding

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation [grant number GA22-27941S].

Open access publishing supported by the National Technical Library in Prague.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM conceived the study, participated in the design, coordination of the study, conducted the literature search and interpretation of the results, and drafted the manuscript; JŠ participated in coordination of the study, supervised the literature search and interpretation of the results, and helped writing the manuscript; DSJ supervised the literature search and interpretation of the results, and helped writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mužík, M., Šerek, J. & Juhová, D.S. The Effect of Civic Engagement on Different Dimensions of Well-Being in Youth: A Scoping Review. Adolescent Res Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00239-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00239-x