Abstract

Little is known about the moderation effect of social support on youth’s civic engagement and meaning in life. To address this research gap, the current study examines the relationship among civic engagement, different sources of social support (family, significant others, and friends), and sense of meaningfulness in life. 1330 High school students in Hong Kong were recruited to participate into a survey in this study. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to examine the possible moderation effect of social support on youth’s civic engagement and meaning in life. The results indicate a positive association between civic engagement and the sense of meaningfulness in life. Social support from family and significant others is also found to be associated positively with the sense of meaningfulness in life. Surprisingly, a negative moderation effect of social support from friends is found in the relationship between civic engagement and the sense of meaningfulness in life, which reminds us to reconsider the nature of friendship support. The results suggest that the government and social workers should continue to facilitate youth participation in civic engagement. Further, more focus should be put on nurturing positive family relationships and support from significant others, from which youth’s sense of meaningfulness can be enhanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There have been abundant research studies conducted to examine the positive impact of civic engagement on youth, especially on their well-being. According to these studies, promoting positive youth development (Balsano, 2005), encouraging reflections on personal agency (Yates & Youniss, 1998), addressing the meaning of the youth’s own ethnicity (Yates & Youniss, 1998), engaging in higher internal locus of control (Zimmerman & Rappaport, 1988), being concerned with connectedness to others (Zimmerman & Rappaport, 1988), and learning and practicing leadership and participatory skills (Jennings et al., 2006) are all identified as related to civic engagement. Although there are benefits to civic engagement, Awan (2016) has pointed out that youth around the globe face a trend of alienation from traditional civic and political engagement, which can be demonstrated by the low involvement in politics in the United States (Snell, 2010) and Canada (Stolle & Cruz, 2005). Recent students on youth civic engagement in Hong Kong indicated a similar trend. For instance, Jackson et al. (2017) found that youth in Hong Kong considered themselves as having low political efficacy and not being effective or having little impact on changing the society. The lack of political efficacy may affect youth’s sense of meaningfulness in life, which has been found to provide purpose in life and facilitate the identity formation of young people (Bronk, 2011).

People who find meaning in life tend to be able to answer the questions of “Why is life meaningful?” and “What provides life with meaning?” (Lambert et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that perceived meaning in life is a protective factor that lowers the level of health risk behaviors and psychosocial symptoms and buffers the effect of political conflicts (Barber, 2009; Brassai et al., 2011; To et al., 2014). However, while some studies investigate the relationship between civic engagement and meaning in life, the interpersonal component of these two constructs seems to be understudied. This is a remarkable oversight, as the significance of social connections in pursuing life meaning (Dewitte et al., 2019; Dunn & O'Brien, 2009; Krause, 2007) and engaging in civic activities has been highlighted in Western societies in general (Flanagan & Bundick, 2011; Kirsch, 2009; Yates & Youniss, 1998), and East Asian culture in particular (Hemmert, 2019; Leung & Au, 2010; Wong & Hong, 2005).

Social support has attained abundant attention from scholars because of its importance on human development and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Numerous studies have been undertaken in academia on the relationship between social support and different constructs such as anxiety and depression (Dour et al., 2014; Holahan & Holahan, 1987), resilience (Sippel et al., 2015), empowerment (Logan & Ganster, 2007), self-efficacy (Wang et al., 2015), and self-esteem (Ikiz & Cakar, 2010). However, as civic engagement involves people who are likely to be mobilized by their social connections and networks, and people tend to make meanings in social connections and relationships (Dewitte et al., 2019; Krause, 2007; To, 2016), little is known about the moderation effect of social support on civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life. Therefore, to fill the research gaps previously mentioned, this paper aims to examine the moderation role of social support on the relationship between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Civic Engagement and Sense of Meaningfulness in Life

Scholars and institutes hardly come to terms with the definition of civic engagement, and there is no consensus on what should (or should not) be defined as civic engagement, what activities should be included in the concept, and from which point of departure should we analyze it. The definition could be as broad as the one provided by Checkoway (2013), that civic engagement is a course of development that “people take collective action to address issues of public concern” or Broom’s (2017) interpretation referring to the term as “interest and participation in civic, political, or social activities.” Flanagan and Bundick (2011) also comprehended the term broadly by only emphasizing the “sense of connection to others and to the common good.” Activities considered part of civic engagement also vary, including donating blood, donating money, volunteering, voting, and participating in community services and public actions. In this article, we have adopted a definition by Adler and Goggin (2005, p. 241) that “Civic engagement describes how an active citizen participates in the life of a community in order to improve conditions for others or to help shape the community’s future,” which emphasizes the social interactions within the community. This could illustrate the important role of different supports during civic engagement.

According to Reker (2000, p. 41), existential meaning can be defined as the “cognizance of order, coherence, and purpose in one’s existence, the pursuit and attainment of worthwhile goals, and an accompanying sense of fulfillment.” More concisely, existential meaning can be understood as containing two interrelated components, namely, sources of meaning and sense of meaningfulness, while the discovery of sources of meaning often leads to the experience of sense of meaningfulness (Ho et al., 2010; To et al., 2014).

Although the number is limited, existing studies have provided us some understanding of civic engagement as a source of meaning. People who engaged in volunteer work, which is considered to be a kind of civic engagement (Flanagan & Bundick, 2011), were found to have a greater sense of meaningfulness than people who did not engage in such activity (Schnell & Hoof, 2012). In addition, civic engagement is believed to directly affect the meaningfulness in life. Pratt and Lawford (2014) have demonstrated that civic engagement would lead to generativity, which is the concern for future generations by passing on cultural values through teaching and mentoring as a legacy, and it is found to be one of the major sources of meaning (Schnell, 2011). Both quantitative and qualitative research on youth also directly or indirectly suggested the relationship between these two constructs. Flanagan and Bundick (2011) contended that university students’ participation in civic affairs would be an important source of meaning derived from their sense of being citizens. A qualitative study by Yates and Youniss (1998) also illustrated the positive relationship between participating in civic engagement and political meaning. Kirsch (2009), when studying students in college, found that when the students had opportunities to write about lived experiences that are meaningful and spiritual, they were more willing to, on the one hand, explore topics related to greater social and civic implications and, on the other hand, reflect their life goals, beliefs, and values. From the limited empirical studies and research suggesting the direct and indirect relationship between the two constructs, the first hypothesis of this study is below:

H1

Civic engagement would be positively associated with sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents living in Hong Kong.

Perceived Social Support Among Adolescents and Their Sense of Meaningfulness in Life

Social support could be defined as “the resources provided by other persons” (Cohen & Syme, 1985) and understood as the process in which individuals mobilize their social networks for material and/or psychological resources so stressful events can be coped with, while social needs and goals could be met and achieved (Rodriguez & Cohen, 1998). It could also be understood in terms of measurement as structural support and functional support. The former refers to the interconnectedness and extent of social relationships, while the latter relates to an individual’s material and resources derived from his/her interpersonal relationship (Rodriguez & Cohen, 1998).

Various studies have been conducted to examine the relationship between social support and meaningfulness in life. In the development of their attachment–meaning framework, Dewitte et al., (2019, p. 2244) suggested that the attachment experiences would facilitate the “development and adaptation of meaning systems, the experience of meaning in life, and the subjective feeling of meaningfulness” as it can contribute to the expansion of meaning by encouraging self and world exploration. Moreover, they contended that love and support from family members and friends could be “a powerful source of meaning in life.” Krause’s (2007) research on social support and meaning in life of older adults could provide reference to support the assumption of the relation between the two constructs. He pointed out that the sense of meaningfulness of older adults is highly related to getting feedback and guidance from someone who can be trusted and receiving emotional support from family and close friendship networks. His study investigated the relationship between social support received from family and close friendship networks and meaning in late life for older adults. The availability of help in the future from significant others is also more likely to enhance older adults’ sense of meaningfulness in life when compared with those who are unsure about its availability. The findings from a research study by Dunn and O'Brien (2009) also indicated that social support from family and significant others is significantly associated with the presence of meaningfulness in life for Spanish-speaking immigrants in the United States.

Studies on young people also supported the relationship between both constructs. A study on the interaction between adolescents’ meaning in life and domain-specific life satisfaction in Hong Kong found that personal meaning is sought from social relationships as adolescents tend to set goals identified with values or expectations of their families and friends (Ho et al., 2010). Additionally, Lambert et al. (2013) indicated that a sense of belonging could predict meaningfulness robustly in their study on undergraduates in the United States. Scholars in general have a consensus that social support could be derived from different sources (Dahlem et al., 1991; Duncan et al., 2005; Li et al., 2014; Sarason et al., 1987). In our study, three different sources of social support—family, friends, and significant others, such as romantic partners and social workers—were measured, considering that our participants are all high school students who may be affected by these three types of social support. Below is the second hypothesis of this study:

H2a

Perceived social support from family would be positively associated with the sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents.

H2b

Perceived social support from significant others would be positively associated with the sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents.

H2c

Perceived social support from friends would be positively associated with the sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents.

Potential Moderating Effect of Perceived Social Support on the Relationship Between Civic Engagement and Sense of Meaningfulness in Life

This paper argues that there would be an amplifying effect of perceived social support (family, friends, and significant others) on the relationship between the two constructs (civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life) based on the theory of relational empowerment by Christens (2012). To further develop the psychological empowerment theory of Zimmerman (1995), a relational component was added to the original model. Christens (2012) contended that a sense of empowerment is derived from and exercised through social relationships, which can support the implementation of transformative power in the sociopolitical field. According to the theory, the relational component of empowerment consists of five dimensions that are closely related to an individual’s social capital and social support: collaborative competence, bridging social divisions, facilitating others’ empowerment, network mobilization, and passing on a legacy. Therefore, civic engagement could be strengthened if participants’ social connection is enhanced, or in other words, the relational component could facilitate others’ sense of empowerment and meaningfulness (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990).

The potential moderating effect of perceived social support is analyzed in this study according to the theoretical argument of relational empowerment (Christens, 2012). An interpersonal dimension of empowerment involves young people developing a sense of belonging and mutual support in the process of youth empowerment, through which youth can derive meaning and purpose from their civic engagement. This suggests that when young people can draw upon supportive networks and social capital to engage in civic activities, it may enhance their feelings of interpersonal empowerment (To et al., 2021). In turn, this newfound sense of interpersonal empowerment stemming from supportive networks and social capital may strengthen young people’s civic engagement, which may further amplify their sense of meaningfulness. Given the existence of a relational component of youth empowerment, it is expected that a synergistic effect exists between perceived social support and civic engagement in terms of their influences on sense of meaningfulness in life.

Previous empirical studies provide evidence to the assumption of the amplifying effect of social support. Albanesi et al. (2007) found that adolescents’ involvement in formal groups is associated with their increased sense of community, including sense of belonging and emotional connection with peers. Such an increased sense of community can also explain some of the association between civic engagement and social well-being. Thus, they suggest that to increase social well-being, it is important to enhance adolescents’ perceived social support and promote civic participation in the community context. Their findings can be argued as implying a synergistic effect between an increased sense of social support and an increased level of civic engagement. Moreover, a recent study undertaken by Xu et al. (2020) show that a positive association between volunteers’ psychological capital such as hope and optimism and their commitment to the volunteer organization was affected by the joint moderating effect of role identification and perceived social support. Given that an increased sense of meaningfulness can be regarded as a form of psychological capital, and civic engagement can be conceptualized as a social process that takes place in both volunteer organizational and community contexts, their findings seem to provide evidence for the moderating effect of social support on the association between sense of meaningfulness and civic engagement. While the target of their study was not young people, the moderating function of perceived social support in youth’s sense of meaningfulness during their participation in civic activities should therefore be examined. Accordingly, the third hypothesis of this study is below:

H3a

Perceived social support from family would moderate the positive association between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents.

H3b

Perceived social support from significant others would moderate the positive association between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents.

H3c

Perceived social support from friends would moderate the positive association between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in the life of adolescents.

Method

A cross-sectional quantitative survey was undertaken targeting high school students because previous findings indicate that the ability to create meaning from civic engagement tends to emerge during middle and late adolescence (Hardy et al., 2011).

Participants

Stratified random sampling was initially adopted to invite 10 schools to participate; however, in view of the lack of schools’ responsiveness due to the impact of COVID-19, stratified purposive sampling was adopted. The schools invited were based on their locations, medium of instruction (mainly Chinese or mainly English), and religious affiliations as stratum. A total of six schools participated in the study covering all specified districts of the city.

There were in total 1330 valid questionnaires collected from October 2020 to March 2021. All respondents were high school students (grades 10 to 12), and the response rate was 67.93%.

Data Collection

Approval from the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong was obtained prior to the study. Permission was also obtained from principals of all participating schools. Letters of consent from both students and parents were collected before the survey. To ensure that the students understood the objectives of the survey, data processing procedures, the principles of anonymity and voluntary participation, and the right of withdrawal, clear explanations were given to them mostly by the researchers, with one exception that one of the schools preferred to deliver and conduct the data collection by teachers. For most of the cases, the researchers administered the data collection process and explained the research to students in a classroom setting on school days. This could help protect respondent anonymity and the use of data. The questionnaires were in Chinese, and instructions were given in Cantonese so that students could easily follow and understand. Questionnaires were collected immediately after completion.

Measures

Independent Variable (IV): Civic Engagement

The Civic Engagement Scale (CES), developed by Doolittle and Faul (2013), aims to measure people’s civic engagement in their communities, and from which the Behavior Subscale was adopted. It is a six-item subscale of CES comprised of questions like “I stay informed of events in my community” and “When working with others, I make positive changes in the community.” The questionnaire adopted a seven-point Likert scale (1 = never, and 7 = always), resulting in a total score from seven to 42. The Chinese version of the subscale validated by Chang et al. (2021) was used in the study with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.925.

Moderating Variable (MV): Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was developed by Zimet et al. (1988). It measures perceived social support from three sources, including family, significant other, and friends. The Chinese-translated version of the scale (MSPSS-C) by Chou (2000) was adopted in the study. Although a two-factor model was generated in Chou’s study (2000), we have adopted the original three-factor model with the consideration that the participants of two studies are different in age—Chou’s study (2000) covered only grade 12 students, while grade 10 to 12 students were recruited in our study. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS Software Version 25 to validate the three-factor model. The goodness-of-fit indices (GFIs), which included the GFI, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) indicated the result to be desirable (GFI = 0.989, CFI = 0.996; RMSEA = 0.035) (specific information about the CFA is available upon request from the corresponding author).

The scale is a 12-item questionnaire with a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Very Strongly Disagree to (7) Very Strongly Agree, with the total score ranging from 12 to 84. Questions such as “My family really tries to help me,” “I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me,” or “I can talk about my problems with my friends” are consistent with the three different sources of social support from family, significant other, and friends, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.937 in this study, and subscale reliability reported alphas of 0.881 (family), 0.915 (significant other), and 0.916 (friends).

Dependent Variable (DV): Sense of Meaningfulness in Life

The subscale Presence of Meaning (MLQ-P) of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire, developed by Steger et al. (2006) and translated by Chan (2014), was used in this study to measure students’ sense of meaningfulness in life. Five items such as “My life has a clear sense of purpose” and “I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful” were included in the scale, which is rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Absolutely Untrue to (7) Absolutely True, with the total score ranging from 5 to 35. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.848.

Control Variables: Demographic Variables

Based on previous research on adolescents (Muldoon et al., 2009; Slone, 2009), the following demographic data of participants was considered to be influential to the relationship among those variables in the hypotheses. Therefore, they were initially considered to be controlled in the regression analyses, which included age, gender, education level, religion, and education level of parents. A further correlation analysis would then decide which one should be controlled in our regression analysis among those potential demographic variables.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were organized in the first phase of the analysis to illustrate the demographic data of the participants. After that, a series of independent t-test, analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed to examine the differences and correlations among all variables studied, including the IV, MV, DV, and all demographic variables.

The second phase of the analysis began with the hierarchical regression analysis to explore the relationship of the IV (civic engagement) and the DV (sense of meaningfulness in life) and the effect of the three MVs (perceived social support from family, friends, and significant other) associated with both previous variables.

Hierarchical regression analysis was performed in four steps. Any variable of demographic covariates that significantly related to the sense of meaningfulness in life was entered in step 1 of the model. The IV civic engagement was entered in step 2. Three different sources (perceived social support from family, perceived social support from significant others, and perceived social support from friends) were entered into the model in step 3. Interaction terms of the IV and each source of perceived social support, which are all mean-centered, were finally entered in the model. Moderating effects could be established by plotting two regression equations at high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of the three sources of the moderator (Aiken et al., 1991). Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

A total of 1330 Hong Kong high school students participated in the study. As shown in Table 1, which indicates the demographic characteristics of the participants, 53.9% were male and 46.1% were female. Among them, 21.1% were aged 15 or below; the majority (67.5%) were aged 16 to 17, while 11.2% were aged 18 to 19, and 0.2% were 20 or above. Of the participants, 74.1% did not have any religion, and the rest (25.9%) confirmed their practice of religion. High school students in grades 10, 11, and 12 were invited to participate in the research, comprising 25.2%, 36.4%, and 38.4% of participants, respectively. Of the participants, 69.9% of their fathers attained at least high school education, and 65.7% of their mothers reached the same level of education.

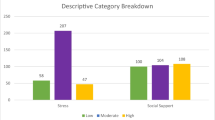

A relatively low level of civic engagement was found in our sample, with its mean scored at 2.765 (SD = 1.329, 95% CI [2.694, 2.836]). By contrast, the level of students’ perceived meaningfulness in life was comparatively high (M = 4.373, SD = 1.144, 95% CI [4.312, 4.435]). Also, the mean scores of their perceived social support from family, significant others, and friends were 4.552 (SD = 1.288, 95% CI [4.483, 4.621]), 4.815 (SD = 1.302, 95% CI [4.745, 4.885]), and 4.974 (SD = 1.223, 95% CI [4.908, 5.040]) respectively, which indicate that the participants in general received a relatively high level of social support from different sources. Moreover, several statistical differences were found in civic engagement and the three sources of perceived social support by demographic variables. For instance, there was a significant difference between male (M = 2.616, SD = 1.315, 95% CI [2.519, 2.712]) and female (M = 2.943, SD = 1.325, 95% CI [2.837, 3.048]) in civic engagement (t (1, 325) = − 4.496, p < .001). Furthermore, two out of three sources of social support, including perceived social support from friends and from significant others, were significantly different by gender. It is found that female (M = 5.078, SD = 1.180, 95% CI [4.984, 5.171]) received more social support from friends than male (M = 4.884, SD = 1.254, 95% CI [4.792, 4.976]). Similarly, female (M = 4.940, SD = 1.223, 95% CI [4.843, 5.037]) obtained more social support from significant others than their counterpart (M = 4.709, SD = 1.359, 95% CI [4.609, 4.809]).

To rule out the effects of demographic variables on the sense of meaningfulness in life (DV), zero-order correlation analysis was conducted among all demographic variables and the DV. Among all demographic variables, only religion was found to be significantly correlated with the sense of meaningfulness in life, r = 0.123, p < 0.001, and therefore it was controlled in the regression analysis. The results also provide preliminary support for the hypotheses that the IV, three MVs, and DV were moderately correlated. Specifically, civic engagement was positively correlated with the sense of meaningfulness in life, r = 0.152, p < 0.001. The three sources of perceived social support, that is, from family (r = 0.272, p < 0.001), significant others (r = 0.304, p < 0.001), and friends (r = 0.242, p < 0.001), were also positively correlated with the sense of meaningfulness in life.

Table 2 presents the result of the hierarchical regression analysis that examined various relationships among civic engagement, sense of meaningfulness in life, and three sources of perceived social support according to the hypotheses mentioned. Hypothesis 1 predicted that civic engagement would be positively associated with the sense of meaningfulness in life. As shown in the table, a statistically significant positive association between the IV (civic engagement) and the DV (sense of meaningfulness in life) is found (β = 0.139, t(1, 1285) = 5.034, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. However, after ruling out the effect of religion, the change in R2 was only 0.019, which indicates a small effect size.

Hypothesis 2a to 2c predicted that the perceived social support from family, significant others, and friends would be positively associated with the sense of meaningfulness in life, respectively. Out of the three sources of perceived social support, support from family [β = 0.129, t(3, 1282) = 3.851, p < 0.001] and significant others [β = 0.206, t(3, 1282) = 4.574, p < 0.001] are statistically significant, while support from friends is not [β = − 0.002, t(3, 1282) = − 0.059, p = 0.953]. Therefore, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported, but Hypothesis 2c was not supported. Furthermore, after controlling the effects of religion and civic engagement while adding the three sources of perceived social support, the change in R2 was 0.086, which indicates a small effect size.

Hypotheses 3a to 3c predicted that the perceived social support from family, significant others, and friends would all moderate the positive association between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life. In this final step, the interaction terms between civic engagement and three sources of perceived social support were entered in the regression model, but the result is insignificant (p = 0.113, ΔR2 = 0.004). Nevertheless, their relationships are more complicated than expected. While no interaction effect was found for perceived social support from family and perceived social support from significant others, a statistically significant negative interaction [β = − 0.104, t(3, 1279) = − 2.186, p < 0.05] between civic engagement and perceived social support from friends is indicated (Fig. 1). It is shown that the strength of the positive relationship between civic engagement (IV) and sense of meaningfulness in life (DV) became stronger for participants who have less perceived social support from friends than those who have better support. In other words, the perceived social support from friends could mitigate the positive association between the IV and the DV. In addition, the whole regression model shows a small effect size (Total R2 = 0.125); this result will be discussed in the following section.

Discussion

Due to limited knowledge on the interpersonal components of civic engagement and meaning in life, the current study has examined the effects of civic engagement and three sources of perceived social support on sense of meaningfulness in life among Hong Kong adolescents. The paper contributes to academia by exploring the relationship between youth’s civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life under a different cultural background ‒ the Hong Kong Chinese one—compared to previous studies (Balsano, 2005; Kirsch, 2009; Xi et al., 2017; Yates & Youniss, 1998). Another focus of the study would be the exploration of the relative importance of three different sources of social support on amplifying the relationship between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life among Hong Kong adolescents.

The positive association between the IV and DV is consistent with our prediction based on a previous review of related studies. The statistically significant and positive association of both variables could be explained by existing theories on meaningfulness in life. According to Baumeister (1991), human beings pursue four needs for meaning: purpose, value, efficacy, and self-worth. Civic engagement is about taking various collective actions related to public issues (Checkoway & Aldana, 2013) that are related to the common good (Flanagan & Bundick, 2011) and can fulfill the purpose of improving conditions and the future of the community and others (Adler & Goggin, 2005). Thus, people who participate in civic engagement can meet at least two of the four needs for meaning, that is, purpose and value.

Specifically, adolescents who participate in civic engagement, which involves pursuing a purpose and advocating some common good, can generate meaningfulness in life. For example, they can use grassroots organizing tactics to call attention to the need to improve inadequate school conditions (Checkoway & Aldana, 2013), which gives them the purposiveness that is related to “future or possible states” (Baumeister, 1991). Their action for the common good is also justifiable due to its meaningfulness. In addition, if the school eventually responds positively to their request, students can harbor the feeling of being capable, united, and respected. Illustrated by the above example, our research seems to provide a convincing explanation for the positive association of the IV and DV.

Another noteworthy finding reflected the importance of social relationships in the Hong Kong context. As shown in Table 2, our hierarchical regression analysis indicated that civic engagement only accounted for 1.9% of the variance of the DV (sense of meaningfulness in life), after controlling the variable of religion. By contrast, the total three sources of perceived social support reached 8.6% after controlling the effects of demographic variable and IV. The results indicated that our participants did not derive much of a sense of meaningfulness in life from getting involved in civic engagement. This is consistent with a previous survey, which demonstrated that over 85% of youth of Hong Kong aged from 15 to 29 never participate in any activities held by organizations of political nature. They were also not eager to join activities with less political elements, as 78.4% of the respondents were found to have not attended any environmental or human rights activities held by related organizations (Hong Kong Institute of Asia–Pacific Studies, 2017).

The reason behind this phenomenon could be attributed to the cultural difference between Eastern and Western societies. It has been well discussed by scholars that countries in East Asia were historically under the influence of Confucian philosophy and adopted an examination-oriented culture (Cho & Chan, 2020; Kwon et al., 2017). As a result, Chinese people pay much attention to pursuing academic excellence, as it was considered as a pathway for upward social mobility (Shek & Siu, 2019), and it has affected Hong Kong students even since they are in elementary schools. According to a qualitative study on grade 5 students in Hong Kong undertaken by Cho and Chan (2020), participants has expressed that they have no time for leisure as the emphasis on grades always means that they need to study out of school by attending academic tutoring. The enormous quantity of homework was also mentioned by the students as the source of frustration. Given that academic excellence is “a desired socialization goal” (Shek & Siu, 2019), it would be reasonable to assume that Hong Kong students’ lack of interest in participating in organized civic activities is likely to result in a low proportion of variance in their sense of meaningfulness in life accounted by their level of civic engagement.

The results of our study also partially supported our hypotheses of the moderator’s main effects on the DV. Perceived social support from family (H2a) and perceived social support from significant others (H2b) are found to be positively associated with sense of meaningfulness in life with statistical significance, while perceived social support from friends (H2c), quite surprisingly, is not found to be significantly associated with the DV. The findings of hypotheses H2a and H2b are consistent with the Positive Adolescent Empowerment Cycle proposed by Chinman and Linney (1998). They contended that before students could become positively empowered, they should be bonded to positive institutions in the society where they can find recognition and positive reinforcement provided by adults (Jennings et al., 2006). As a result, the model could extend to not only covering adults in positive institutions, but also to family members and significant others from whom adolescents received positive support, and they tend to be empowered and consider life meaningful. The finding is also supported by other scholars’ arguments. For example, Pancer (2014) suggested that parents and families are vital in their roles of developing the values of individuals, and they are also considered to be the vehicles to transfer community and cultural norms for their children. Rossi et al. (2016) also suggested a similar impact from family. As a significant other can be defined as someone who deeply influences one’s life and in whom one has emotionally invested (Andersen & Chen, 2002), it can be regarded as serving the same function as a family member. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that the impact of family on meaning in life can also extend and apply to significant others surrounding adolescents, such as teachers, social workers, and romantic partners.

However, our finding contradicts Hypothesis H2c and other existing research findings on the role of social support from friendship. One possible explanation could be related to the two sides of the effects of friendship. Although good friendship can result in positive features such as encouragement, self-esteem support, and prosocial behavior (Berndt, 2002), its negative features such as experiencing conflicts with friends, engaging in rivalry, and dominance attempts can be observed even between best friends. Another study by Agnew (1991) indicated that serious delinquency is related to higher levels of peer interaction from friends with serious delinquency. These negative experiences eventually generate loneliness and boredom (Berndt, 2002; Newberry & Duncan, 2001), and they are found to be negatively related to the presence of meaning (Newberry & Duncan, 2001; To et al., 2016). Therefore, when participants experience negative features of friendship, they might not be able to create meaning in life even though some positive effects of being engaged in friendship are present. However, further research should be performed to fully comprehend the relationship between quality of friendship and meaningfulness in life.

Interestingly, two of the proposed interaction effects, between civic engagement and social support from family (H3a) and between civic engagement and social support from significant others (H3b), are insignificant, while the one between civic engagement and friends reached statistical significance with a negative association. In other words, when adolescents have better social support from friends, the effect of civic engagement on sense of meaningfulness in life would decrease. This implied that an individual could find more meaning when engaging in civic actions with casual or distant friends who may give less social support than with close friends who may provide more social support. One possible explanation of the Hypothesis H3c could be illustrated by Harris’s socialization system theory (2010).

According to Harris (2010), when children engage in the process of socialization, they tend to average the collected information to prototypes that can be used as models to follow. This helps prevent children from only imitating an atypical example, which can likely be someone close to them. Similarly, Giordano (2003) contended that the wider network of friends could provide adolescents with information about the broader cultural world and their social worth through direct and indirect communication processes. He suggested that because the number of young people’s wider network of friends is typically more than that of close friends, thus it should be considered as an important evaluative force. Akerlof and Rachel (2002) also argued that a young person’s identity is affected by his/her perceived social categories defined by the wider circle of friends in a social setting.

Building on Harris’ socialization theory, Carbonaro and Workman (2013) proposed that a socially acceptable norm could be built according to the characteristics of distant friendship, from which different social categories would be sorted out by the socialization system. In other words, the characteristics of young people’s distant friends may be more likely to help shape their identity and beliefs about “what is normative” when comparing with close friends. However, instead of providing a normative framework, close friendship provides a comfort zone where people feel less constrained by the expectations of their close friends (Carbonaro & Workman, 2013). Therefore, when youth get involved in civic engagement with their close friends, they might not be able to devote themselves to activities, given that they can act more freely according to their will, diminishing the commitment and the sense of meaningfulness derived from the activities. By contrast, when youth work with casual or distant friends in civic engagements, the behaviors of casual or distant friends would be set as norms and would be less flexible, leading to better commitment to the activities and a greater sense of meaningfulness in life. Nevertheless, the reciprocity process of the influence from close and distant friendship on civic engagement and meaningfulness in life is subject to further study.

Several limitations were present in the current study. Firstly, as shown in the result, it is clear that only 1.9% of the variances could be attributed to civic engagement, which means many other factors can contribute to the sense of meaningfulness in life. However, this research is unable to examine these factors. Secondly, as it is a cross-sectional study, the causal influence of the IV and DV could not be determined. Our study hypothesizes that civic engagement would lead to a sense of meaningfulness in life. However, several civic models (Broom, 2017; Watts et al., 1999) implied a reciprocal nature of civic engagement and meaning in life: While civic engagement could lead to sense of meaningfulness, it can also facilitate civic engagement when youth understand more about their meaning in life. Hence, the result of the paper should be cautiously interpreted. Thirdly, bias might be present when historic events happen. Unfortunately, two major events occurred during the research period—the COVID-19 pandemic and the promulgation of the National Security Law in Hong Kong—which can heavily influence the results of the research, considering that people faced anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, as most of our participants completed the questionnaires in a classroom setting when researchers were present, social desirability may have occurred. Furthermore, as the survey questionnaire is self-reporting and self-administrated, biases such as response bias and recall bias might be possible. Finally, the CES, which was adopted in this research, could not distinguish between different kinds of civic engagement, whether it is prosocial or protest-oriented, so the generalization of the results should be interpreted with caution.

Implications

Although only accounting for a small proportion of the variance on the sense of meaningfulness in life, our results support the hypothesis of the positive association between civic engagement and sense of meaningfulness in life; the current findings can thus provide insights into local youth programs. For example, an action research undertaken by Su et al. (2014) on Chinese university students living in Taiwan indicated that university students’ civic engagement via service-learning in organizing a study group for elementary students could lead to an enhancement of meaningful in life, together with an improvement of communication and engagement in peer groups. According to the researchers, the strength of this program is its integration of supports from faculty members and other fellow students, as well as interactions with service users, which seems to echo our findings on the influence of social support from a wider circle of friends like service users and significant others like university teachers. Service-learning can thus be considered as a type of civic engagement that can help enhance meaning in life based on a strengthened sense of social support.

In Hong Kong, a study undertaken by To and Liu (2021) further showed that an adoption of design thinking in community-based youth empowerment programs was beneficial to young people’s creative self-efficacy and perceived youth-adult partnerships in the community. Their findings may align with the notion of adults’ involvement and partnerships with young people in civic engagement. Community-based youth empowerment programs adopting design thinking can therefore be regarded as another direction for enhancing civic engagement and meaning in life via strengthening a wider network of social support in the community.

In addition, the Hong Kong government should continue to promote civic engagement among young people in various forms such as volunteering, serving in communities, joining public consultations, or even engaging in social actions for advocacy. To empower youth and enhance their sense of meaningfulness in life, the government should consider involving more youth voices in policy formulation by establishing a youth council so youth could be more engaged in civic affairs and policymakers could recognize their voices.

As social support from family is found to enhance youth’s sense of meaningfulness in life, it is advised that the government should provide support to family so the relationship between family and adolescents could be improved, which leads to an increase in their sense of meaningfulness in life. One suggestion is to construct a family-friendly environment to help improve family relationships in Hong Kong families.

Social workers can also review their mode of practice with the reference of this study. Social workers have the responsibility to facilitate the self-realization of clients and encourage youth’s involvement in civic engagement (Social Workers Registration Board, 2013), which could, to some extent, enhance their sense of meaningfulness in life. Despite the precarious and unpredictable sociopolitical condition of Hong Kong, it is still feasible and important for social workers and social service agencies to organize civic engagement activities such as volunteering, community building, and intergroup dialogue with the youth and other people of Hong Kong.

In addition, as social workers are required to connect people to enhance clients’ well-being (Social Workers Registration Board, 2013), more attention should be given to examining the social support network of youths. Knowing the significance of the role of family and significant others on youth’s sense of meaningfulness in life, social workers, as one of the significant others who can facilitate family and other close relationships, should be able to develop skills and flexibility to promote or strengthen social support for youth who have a low sense of meaningfulness in life. They should also act as educators in the community about the importance of social support for youth so teachers, significant others, and parents can provide the necessary support for adolescents who are still forming their identities and creating meaning in life.

Conclusion

The current study examines the relationship among civic engagement, different sources of social support (perceived social support from family, perceived social support from significant others, and perceived social support from friends), and sense of meaningfulness in life. It is found that the IV (civic engagement) and DV (sense of meaningfulness in life) were significantly associated in a positive direction. It is also consistent with our hypotheses that two of the MVs (perceived social support from family and perceived social support from significant others) were positively associated with the DV. The findings would help academia understand the complex reciprocity involved in civic engagement, especially in the Hong Kong context. Specifically, more studies in the future should examine the role of social support in civic engagement and meaning in life, especially in view of the current findings of a negative moderating effect of perceived social support from friends.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to datasets containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Adler, R. P., & Goggin, J. (2005). What do we mean by “civic engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3(3), 236–253.

Agnew, R. (1991). The interactive effects of peer variables on delinquency. Criminology, 29(1), 47–72.

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Akerlof, G. A., & Rachel, K. E. (2002). Identity and schooling: Some lessons for the economics of education. Journal of Economic Literature, XL, 1167–1201.

Albanesi, C., Cicognani, E., & Zani, B. (2007). Sense of community, civic engagement and social well-being in Italian adolescents. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 17(5), 387–406.

Andersen, S. M., & Chen, S. (2002). The relational self: An interpersonal social–cognitive theory. Psychological Review, 109(4), 619–645.

Awan, A. (2016). Negative youth engagement: Involvement in radicalism and extremism. In U. Nations (Ed.), World Youth Report (pp. 87–94). United Nations.

Balsano, A. B. (2005). Youth civic engagement in the United States: Understanding and addressing the impact of social impediments on positive youth and community development. Applied Developmental Science, 9(4), 188–201.

Barber, B. K. (2009). Making sense and no sense of war: Issues of identity and meaning in adolescents’ experience with political conflict. In B. K. Barber (Ed.), Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence (pp. 281–311). Oxford University Press.

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. Guilford Press.

Berndt, T. J. (2002). Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 7–10.

Brassai, L., Piko, B. F., & Steger, M. F. (2011). Meaning in life: Is it a protective factor for adolescents’ psychological health? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18(1), 44–51.

Bronk, K. C. (2011). The role of purpose in life in healthy identity formation: A grounded model. New Directions for Youth Development, 2011(132), 31–44.

Broom, C. (2017). Youth civic engagement in context. In C. Broom (Ed.), Youth civic engagement in a globalized world: Citizenship education in comparative perspective (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan.

Carbonaro, W., & Workman, J. (2013). Dropping out of high school: Effects of close and distant friendships. Social Science Research, 42(5), 1254–1268.

Chan, W. C. H. (2014). Factor structure of the Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire among Hong Kong Chinese caregivers. Health and Social Work, 39(3), 135–143.

Chang, C. W., To, S. M., Chan, W. C. H., & Fong, A. C. P. (2021). The influence of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community protective factors on Hong Kong adolescents’ stress arising from political life events and their mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189426

Checkoway, B., & Aldana, A. (2013). Four forms of youth civic engagement for diverse democracy. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(11), 1894–1899.

Chinman, M. J., & Linney, J. A. (1998). Toward a model of adolescent empowerment: Theoretical and empirical evidence. Journal of Primary Prevention, 18(4), 393–413.

Cho, E. Y. N., & Chan, T. M. S. (2020). Children’s wellbeing in a high-stakes testing environment: The case of Hong Kong. Children and Youth Services Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104694

Chou, K. L. (2000). Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(2), 299–307.

Christens, B. D. (2012). Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 114–128.

Cohen, S., & Syme, S. L. (1985). Issues in the study and application of social support. Social Support and Health, 3, 3–22.

Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, G. D., & Walker, R. R. (1991). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support: A confirmation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(6), 756–761.

Dewitte, L., Granqvist, P., & Dezutter, J. (2019). Meaning through attachment: An integrative framework. Psychological Reports, 122(6), 2242–2265.

Doolittle, A., & Faul, A. C. (2013). Civic engagement scale: A validation study. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013495542

Dour, H. J., Wiley, J. F., Roy-Byrne, P., Stein, M. B., Sullivan, G., Sherbourne, C. D., ..., Craske, M. G. (2014). Perceived social support mediates anxiety and depressive symptom changes following primary care intervention. Depression and Anxiety, 31(5), 436–442.

Duncan, S. C., Duncan, T. E., & Strycker, L. A. (2005). Sources and types of social support in youth physical activity. Health Psychology, 24(1), 3–10.

Dunn, M. G., & O’Brien, K. M. (2009). Psychological health and meaning in life: Stress, social support, and religious coping in Latina/Latino immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(2), 204–227.

Flanagan, C., & Bundick, M. (2011). Civic engagement and psychosocial well-being in college students. Liberal Education, 97(2), 20–27.

Giordano, P. C. (2003). Relationships in adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology, 29(1), 257–281.

Hardy, S. A., Pratt, M. W., Pancer, S. M., Olsen, J. A., & Lawford, H. L. (2011). Community and religious involvement as contexts of identity change across late adolescence and emerging adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 125–135.

Harris, J. R. (2010). No two alike: Human nature and human individuality. W.W. Norton & Company.

Hemmert, M. (2019). The relevance of inter-personal ties and inter-organizational tie strength for outcomes of research collaborations in South Korea. Asia–Pacific Journal of Management, 36(2), 373–393.

Ho, M. Y., Cheung, F. M., & Cheung, S. F. (2010). The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 658–663.

Holahan, C. K., & Holahan, C. J. (1987). Self-efficacy, social support, and depression in aging: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Gerontology, 42(1), 65–68.

Hong Kong Institute of Asia–Pacific Studies. (2017). Youth political participation and social media use in Hong Kong—Research Report. http://youthstudies.com.cuhk.edu.hk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Research-Report_Youth-Political-Participation-and-Social-Media-Use-in-Hong-Kong.pdf.

Ikiz, F. E., & Cakar, F. S. (2010). Perceived social support and self-esteem in adolescence. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 2338–2342.

Jackson, L., Kapai, P., Wang, S., & Leung, C. Y. (2017). Youth civic engagement in Hong Kong: A glimpse into two systems under one China. In C. Broom (Ed.), Youth civic engagement in a globalized world: Citizenship education in comparative perspective (pp. 59–86). Palgrave Macmillan.

Jennings, L. B., Parra-Medina, D. M., Hilfinger-Messias, D. K., & McLoughlin, K. (2006). Toward a critical social theory of youth empowerment. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1–2), 31–55.

Kirsch, G. E. (2009). From introspection to action: Connecting spirituality and civic engagement. College Composition and Communication, 60(4), W1–W15.

Krause, N. (2007). Longitudinal study of social support and meaning in life. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 456.

Kwon, S. K., Lee, M. B., & Shin, D. K. (2017). Educational assessment in the Republic of Korea: Lights and shadows of high-stake exam-based education system. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 24(1), 60–77.

Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427.

Leung, H., & Au, W. W. T. (2010). Chinese cooperation and competition. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 499–514). Oxford University Press.

Li, H., Ji, Y., & Chen, T. (2014). The roles of different sources of social support on emotional well-being among Chinese elderly. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e90051. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090051

Logan, M. S., & Ganster, D. C. (2007). The effects of empowerment on attitudes and performance: The role of social support and empowerment beliefs. Journal of Management Studies, 44(8), 1523–1550.

Muldoon, O., Cassidy, C., & McCullough, N. (2009). Young people’s perceptions of political violence: The case of Northern Ireland. In B. K. Barber (Ed.), Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence (pp. 125–144). Oxford University Press.

Newberry, A. L., & Duncan, R. D. (2001). Roles of boredom and life goals in juvenile delinquency 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 527–541.

Pancer, S. M. (2014). The psychology of citizenship and civic engagement. Oxford University Press.

Pratt, M. W., & Lawford, H. L. (2014). Early generativity and types of civic engagement in adolescence and emerging adulthood. In L. M. Padilla-Walker & G. Carlo (Eds.), Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach (pp. 410–436). Oxford University Press.

Reker, G. T. (2000). Theoretical perspective, dimensions, and measurement of existential meaning. In G. T. Reker & K. Chamberlain (Eds.), Exploring existential meaning: Optimizing human development across the life span (pp. 39–55). Sage.

Rodriguez, M. S., & Cohen, S. (1998). Social support. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mental health (Vol. 3, pp. 535–544). Academic.

Rossi, G., Lenzi, M., Sharkey, J. D., Vieno, A., & Santinello, M. (2016). Factors associated with civic engagement in adolescence: The effects of neighborhood, school, family, and peer contexts. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(8), 1040–1058.

Sarason, B. R., Shearin, E. N., Pierce, G. R., & Sarason, I. G. (1987). Interrelations of social support measures: Theoretical and practical implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 813.

Schnell, T. (2011). Individual differences in meaning-making: Considering the variety of sources of meaning, their density and diversity. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 667–673.

Schnell, T., & Hoof, M. (2012). Meaningful commitment: Finding meaning in volunteer work. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 33(1), 35–53.

Shek, D. T. L., & Siu, A. M. H. (2019). “UNHAPPY” environment for adolescent development in Hong Kong. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(6), S1–S4.

Sippel, L. M., Pietrzak, R. H., Charney, D. S., Mayes, L. C., & Southwick, S. M. (2015). How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecology and Society, 20(4), 10.

Slone, M. (2009). Growing up in Israel: Lessons on understanding the effects of political violence on children. In B. K. Barber (Ed.), Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence (pp. 81–104). Oxford University Press.

Snell, P. (2010). Emerging adult civic and political disengagement: A longitudinal analysis of lack of involvement with politics. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(2), 258–287.

Social Workers Registration Board. (2013). Code of Practice. Social Workers Registration Board. https://www.swrb.org.hk/en/Content.asp?Uid=14.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80.

Stolle, D., & Cruz, C. (2005). Youth civic engagement in Canada: Implications for public policy. Social Capital in Action, 82, 82–144.

Su, Y. L., Pan, R. J., & Chen, K. H. (2014). Encountering selves and others: Finding meaning in life through action and reflection on a social service learning program. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 8(2), 43–52.

Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666–681.

To, S. M. (2016). Loneliness, the search for meaning, and the psychological well-being of economically disadvantaged Chinese adolescents living in Hong Kong: Implications for life skills development programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 71, 52–60.

To, S. M., & Liu, X. Y. (2021). Outcomes of community-based youth empowerment programs adopting design thinking: A quasi-experimental study. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(7), 728–741.

To, S. M., Tam, H. l., Ngai, S. S. Y., & Sung, W. L. (2014). Sense of meaningfulness, sources of meaning, and self-evaluation of economically disadvantaged youth in Hong Kong: Implications for youth development programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 352–361.

Wang, C. M., Qu, H. Y., & Xu, H. M. (2015). Relationship between social support and self-efficacy in women psychiatrists. Chinese Nursing Research, 2(4), 103–106.

Watts, R. J., Griffith, D. M., & Abdul-Adil, J. (1999). Sociopolitical development as an antidote for oppression—Theory and action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 255–271.

Wong, R. Y. M., & Hong, Y. Y. (2005). Dynamic influences of culture on cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemma. Psychological Science, 16(6), 429–434.

Xi, J., Lee, M., LeSuer, W., Barr, P., Newton, K., & Poloma, M. (2017). Altruism and existential well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12(1), 67–88.

Xu, L., Wu, Y., Yu, J., & Zhou, J. (2020). The influence of volunteers’ psychological capital: Mediating role of organizational commitment, and joint moderating effect of role identification and perceived social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00673

Yates, M., & Youniss, J. (1998). Community service and political identity development in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 54(3), 495.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41.

Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581–599.

Zimmerman, M. A., & Rappaport, J. (1988). Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(5), 725–750.

Acknowledgements

The data for this study was collected with the support from six schools in Hong Kong. Special thanks are due to the schools for supporting and participating in this study.

Funding

This research project (Project Number 2020.A4.067.20B) is funded by the Public Policy Research Funding Scheme from the Policy Innovation and Co-ordination Office of The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University (Reference No. SBRE-19-131).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Parental informed consent was obtained from all subjects aged under 18.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fong, CP., To, Sm. Civic Engagement, Social Support, and Sense of Meaningfulness in Life of Adolescents Living in Hong Kong: Implications for Social Work Practice. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 41, 161–173 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00819-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00819-7