Abstract

The literature to date has documented the presence of challenges and barriers in mental health systems and services for children and adolescents worldwide. However, studies addressing this reality often do so in a fragmented, residual, incomplete, or generalized way, therefore hindering a comprehensive understanding of this complex phenomenon. The aim of this qualitative systematic review is to analyze the barriers and challenges affecting global mental health care for children and adolescents. Searches were made in the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed databases between 2018 and 2022 using terms connected with mental health, childhood, adolescence, and health systems. The search resulted in the extraction of 9075 articles, of which 51 were considered eligible for inclusion and complied with quality indicators. A number of closely related structural, financial, attitudinal, and treatment barriers that limited the quality of life and well-being of children and adolescents with mental health needs were found. These barriers included inadequate public policies, operational deficiencies, insufficient insurance coverage, privatization of services, stigma, lack of mental health literacy, lack of training, overburdened care, dehumanization of care, and lack of community and integrated resources. The analysis of these barriers displays that this treatment gap reflects the historical injustice towards mental illness and the disregard for real needs in these crucial stages, perpetuating a systematic lack of protection for the mental health of children and adolescents. The complexity of the disorders and the absence of public resources have resulted in a hodgepodge of mental health services for children and adolescents that fails to provide the continuing specialist health care they need.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health in childhood and adolescence (CAMH) represents a challenge for public health in most countries of the world and has been included as a priority in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015). Although there is growing awareness of the importance of mental health at these ages, the attention given to CAMH has until recently been disproportionately low compared to that given to mental disorders that affect adults or physical illnesses (Mokitimi et al., 2019). Thus, seems as CAMH tends to be overlooked and neglected on a global level (Simelane & de Vries, 2021). Research on CAMH has empirically substantiated the presence of obstacles and impediments to accessing and participating in ongoing healthcare services. However, the results frequently appear fragmented or generic, hindering a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. Consequently, the literature continues to emphasize the need to focus on the trends, barriers and facilitators of CAMH care system utilization in different contexts in order to guide future policy development (Hossain et al., 2022). To this end, qualitative methodology, focusing on subjective experience, has been considered the most suitable method to better understand the needs of service providers and consumers and to improve the guidelines aimed at providing better practice and access to quality care (Noyes et al., 2019; Wainwright & Macnaughton, 2013). Nevertheless, despite the growing biomedical interest in incorporating people's experiences into research, research on disparities and challenges in mental health care has been predominantly quantitative to this date. There are several systematic reviews that already provide an overview of available quantitative data on barriers (e.g., Ghafari et al., 2022; Verhoog et al., 2022). Therefore, the present study aims to address this research gap and synthesize the existing qualitative literature by systematically reviewing in order to identify and comprehensively define barriers and challenges in global child and adolescent mental health care. Special attention is given to the critical analysis of the nature and causes of these challenges drawn from the current literature with the objective of enriching the understanding and facilitating the development of more realistic and effective interventions and policies in the future.

Around 20% of children and adolescents worldwide may experience some kind of mental health problem in any given year and it is calculated that half of all mental disorders begin at age 14 (WHO, 2021). Adolescence is therefore considered to be a critical stage in the development of these conditions, which represent 16% of the global burden of disease (WHO, 2022a; Save the Children, 2021). These reports indicate that depression is one of the main causes of illness and disability among adolescents, with suicide being the second most common cause of death among those aged 15 to 19. Results from different studies show that the rate of mental disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults has increased by up to 20% in recent decades, with mood disorders being the most affected area (e.g., Pitchforth et al., 2019). This rate has increased out of proportion since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Geweniger et al., 2022). The most recent reviews (Panchal et al., 2021; Samji et al., 2022) state that children and adolescents affirm that their mental health worsened during this period, with figures ranging between 2 and 74%. Despite the ever-increasing prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents, most cases are neither detected nor treated. Indeed, studies show that only a minority of children and adolescents with disorders receive help from mental health care services specifically for children and adolescents (Rocha et al., 2015), i.e. CAMH services, and in most cases, they have to wait a long time before they receive specialist care (Raven et al., 2017). This gap in care can have a serious effect on wellbeing and development in children and adolescents, who are now identified as a particularly vulnerable group (WHO, 2022b). The lack of detection and timely treatment may contribute to the progression of the disorder and increase the chances of serious consequences in later life, including severe mental health problems (Raballo et al., 2021), difficulty in maintaining physical health (Xu et al., 2022) and problems with establishing healthy social relationships and achieving academic and professional goals (Al-Adawi et al., 2023).

Healthcare systems should provide adequate and financially fair services in order to avoid negative future outcomes and improve the well-being and personal productivity of children and adolescents (UNICEF, 2016). However, various studies (e.g., Kaku et al., 2022) report that healthcare systems and CAMH services are limited and inadequate all over the world, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (Simelane & de Vries, 2021). However, it is worth noting that inefficient and inaccessible mental healthcare models can also be found in medium- and high-income countries (HMICs) (Carbonell et al., 2020). A recent scoping review suggests that insufficient funding and a lack of qualified professionals are some of the factors that hinder the development and spread of CAMH services (Babatunde et al., 2021). Additionally, the social stigma and lack of awareness associated with mental health also act as barriers preventing people from seeking treatment (Mugisha et al., 2020). In fact, there are a great many gaps affecting access to and provision of CAMH services that need to be dealt with in order to reduce the burden of illness and improve the quality of the system and of mental health in general (Abidi, 2017; Paula et al., 2014).

Several studies point out that these limitations (such as disparities in access, rising costs, or poor quality of care) are closely related to the lack of coordination and poor communication among multiple services and care providers, leading to fragmented systems and services (Carbonell et al., 2023; Kaur et al., 2022). Given these deficiencies, the literature (Khanal et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2022) highlights the need to strengthen mental health systems worldwide, regardless of countries’ income levels. The action plan designed to address deficiencies in mental health care (mhGAP) developed by the WHO (2016) establishes a package of interventions for the prevention and handling of CAMH aimed at eliminating the distance between the capacity of health systems and the services available. However, recent investigations indicate that a stronger commitment is needed to improve the social determinants of CAMH and to explore the gaps in mental health in order to develop more effective and more robust mental health systems in the future (Elharake et al., 2022; Racine et al., 2021).

As highlighted by studies, it is crucial to promote coordinated and integrated care systems that holistically address the real needs of CAMH (De Voursney & Huang, 2016). In order to achieve this, the development of effective public policies and strategies that improve the quality of care, reduce the treatment gap, and promote direct service provision and remodeling are needed. To this end, a recent umbrella review argued that there is a need to identify the trends, barriers, and facilitators found in connection with the use of mental health services by children and adolescents in different contexts as a key driver for future policy formulation (Hossain et al., 2022). However, there is a tendency to identify them in a residual or fragmented way. In fact, the synthesis of the evidence has often focused on the analysis of specific geographic settings (Iversen et al., 2021), specific groups (Holt, 2022), specific mental disorders (Maurice et al., 2022), providers' perspectives (O'Brien et al., 2016), help-seeking behaviors (Aguirre, 2020), systemic or professional factors (Banwell et al., 2021), or have methodological limitations (Hendrickx et al., 2020), without providing a comprehensive and rigorous understanding of the reality. Likewise, research on disparities and challenges in child and adolescent mental health care has focused primarily on quantitative data. Thus, the limitations perpetuated by the system itself or the nature and causes of these limitations have remained underexplored and, therefore, require greater attention in future research (Orth & van Wyk, 2022). Qualitative research has been less common in this field. This fact is unfortunate, as qualitative research methods are essential to understand the real needs of service providers and consumers, and provide an in-depth understanding of the processes and interactions that underlie the observed outcomes (Noyes et al., 2019; Wainwright & Macnaughton, 2013). Despite the numerous researchers who have integrated personal experiences into understanding and addressing mental health challenges (O‘Neill et al., 2023), systematic reviews to date have failed to comprehensively examine the available qualitative literature from the perspective of all the actors involved. Under these considerations, the literature shows the need for a holistic and qualitative analysis of the barriers faced by people accessing, using, deciding on, or working professionally with CAMH services.

In this regard, following the policy cycle framework (Chindarkar et al., 2022), problem identification and definition constitute the initial phase of policy development. This stage allows for understanding the nature and magnitude of the problem and establishing appropriate objectives and strategies to address it (Poblador & Lagunero-Tagare, 2023). A precise definition of system challenges is essential for informed decision-making, considering the involvement and experiences of all stakeholders and enabling effective resource allocation and interventions (Baltag & Servili, 2016; Harguindéguy, 2020). Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the simple identification of these barriers is not enough to fully understand the phenomenon and address it effectively. Only through a deep understanding of the underlying reasons and trends of these barriers is possible to guide future research that analyzes evidence-based solutions to maximize the development and impact of policies and strategies, improve care, overcome existing gaps in care systems, and advance the field of CAMH.

Current Study

Although research to this date has documented the presence of barriers in CAMH, previous studies addressing this reality often do so in a fragmented, residual, incomplete, or generalized manner. In this regard, the evidence shows gaps in the comprehensive understanding of the complexity of the phenomenon. So far no qualitative systematic review has been carried out that provides a critical, explanatory, full, and exhaustive overview picture of the current situation. Thus the purpose of the present study is to summarize the literature and analyze the barriers and challenges that exist in global mental health care for children and adolescents. This review aims to go beyond problem identification and provide a rigorous and exhaustive analysis to offer clear and evidence-based explanations of the nature and causes of these challenges.

Methods

Search Strategy

Included studies had to be scientific articles in English language that followed a qualitative approach and had been published over the last five years (2018–2022) and which directly or indirectly examined the barriers and challenges of mental health care for children and adolescents and their families. In order to ensure the quality of the data, inclusion criteria were limited to studies published exclusively in journals with a peer review process. Documents without full access, those published as grey literature, and those that involved a population with a primary diagnosis that was not a mental health problem (e.g. cystic fibrosis, HIV and cancer) were excluded. Studies that provided no information about their methods or data collection procedures were also excluded.

The data search through the Web of Science, Scopus and PubMed databases continued until 31 December 2022. The keywords for the search were broken down into four groups. The first covered challenges, barriers, and limitations; the second comprised descriptors relating to mental health systems and policies; the third covered the main concepts relating to childhood and adolescence; and the fourth focused on terms associated with health and mental disorders. As can be seen in Table 1, the Boolean operators OR and AND were used with truncation symbols with the key search descriptors in the title, description, and keyword fields.

Data Extraction and Analysis

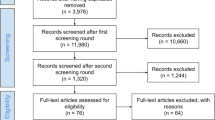

For the data analysis, the selection process for documents is shown below in the shape of a PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021). Each article was selected on the basis of the following descriptive aspects: authors and year of publication, country, study design, sample, and main results. An interpretive synthesis of the chosen studies was then made using deductive-mixed content analysis, which consisted of studying the findings of the included studies in two phases (Finfgeld-Connett, 2014). First, aprioristic areas were established from the scientific literature, integrating the categories and subcategories within each of them. Subsequently, the main categories and subcategories emerging from the data collected were analyzed. To this end, an open categorization process was carried out, the purpose of which was to break down the data and group them into different categories that shared the same unit of meaning (Boyatzis, 1998; Coffey & Atkinson, 2003). This allowed the establishment of a panoramic, cross-sectional, and structural view of the object of study.

Quality Assessment

PRISMA guidelines (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) (Page et al., 2021) were followed to ensure the quality and transparency of the review process. Risk of bias and the methodological quality of all the studies included were assessed to determine the validity of the results. For this purpose, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP, 2023)—Checklist for Qualitative Studies (Long et al., 2020; Singh, 2013) was used. This tool is comprised of 10 questions that individually and critically assess the reports of the results of qualitative research. The scores are categorized into three quality levels: low (0–3 points), medium (4–7 points) and high (8–10 points). No articles were excluded at this point.

The literature search, study selection, data extraction, narrative analysis, and quality assessment were all carried out by two of the authors (AC, JJNP) working separately. If disagreements arose during the process, consensus was reached through discussion with a third author (SG). A fourth author supported the entire research process (VPC). This made it possible to ensure objectivity and reduce any bias in the review (Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012; Wainwright & Macnaughton, 2013).

Results

Number of Studies Included

The results of the search and selection process are shown in Fig. 1. A total of 51 articles were selected for final inclusion.

Characteristics of the Studies Included

Table 2 lists the methodological characteristics and quality of the studies included. All articles obtained high or medium-quality indicators. As regards to research methodology, most of the studies (72.55%) used semi-structured interviews as their data collection technique, compared to eight (15.69%) that used focus groups and six (11.75%) that combined various qualitative techniques. The distribution by year shows that research interest in the subject has been growing.

The included studies directly or indirectly analyzed the barriers and challenges of mental health care in childhood and adolescence from different perspectives. Sixteen of them (31.37%) analyzed the perceptions of service providers and professionals involved in mental health, 12 (23.53%) collated the experiences of the children and adolescents themselves, and 10 (19.61%) focused on the point of view of the parents or carers. The remaining studies combined different perspectives and experiences in their analysis. In addition, 6 studies (11.76%) concentrated solely on the limitations that arose during the transition from child and adolescent to adult mental health care, while 12 studies (23.53%) focused on vulnerable collectives such as immigrants and refugees, racialized people, ethnic minorities and children and adolescents involved in the child welfare system. A big proportion of included articles (94.12%) were carried out in high- and upper-middle-income countries.

Barriers to Mental Health Care in Childhood and Adolescence

Five descriptive categories were found regarding the challenges and barriers in mental health care for children and adolescents: (a) systemic or structural barriers, (b) financial resources, (c) attitudes to treatment, (d) professional intervention, and (e) shortcomings of the biomedical model. These categories were broken down into a total of 30 subcategories, as shown in Table 3.

Systemic or Structural Barriers

The analyzed studies found structural barriers in the provision of services. These involved operating defects or inefficiencies in the health system that give rise to a treatment gap in mental health (Banks, 2022; Radez et al., 2021) visible in the difference between the number of children and adolescents who need care and those who actually receive it. The study on adolescents in Kenya discovered legislative vacuums and a lack of creation and implementation of public policies, strategies, and specific actions on the part of the government and other entities (Memiah et al., 2022). As a result, access to and provision of mental health services for children and adolescents may be inadequate and limited in terms of accessibility, quality, and coverage, especially in disadvantaged communities and low-resource settings (Nhedzi et al., 2022; Paton et al., 2019). The health system’s sociopolitical structure that tends towards the geographic decentralization of care—along with the pluralist structure that combines public providers with private resources and professionals—makes access to and provision of mental health services an arduous task (Paton & Hiscock, 2019).

In most countries, there is clear segregation between the provision of physical and mental pediatric health care, characterized by a physical and organizational separation between these services. This situation can lead patients to seek care in various locations or from different providers, posing challenges in coordinating, maintaining continuity, and ensuring the quality of the resources available to provide medical care. As many studies (Crouch et al., 2019; Kalucy et al., 2019; Memiah et al., 2022; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Platell et al., 2020; Putkuri et al., 2022; Zifkin et al., 2021) point out, the lack of resources and funding is evidence of the low priority given to mental health, limiting the development of plans and budgets aimed at mental disorders. In one study involving children, adolescents, and community providers, the participants argued that mental health needs to be opened and given the same standing as physical health, more accepted and better understood (Nhedzi et al., 2022). Another study reports that services in the Australian health system are fragmented and characterized by the priority given to physical development and the absence of a road map to guide people through mental health services for children and adolescents (Paton et al., 2021). The results show that both services need to be integrated into the same physical space, that funding for time planning and case consultation should be increased, and that multidisciplinary assessments should be carried out in conjunction with other services in order to provide the best quality care.

The rigidity of the mental health system for children and adolescents and the weakness of the referral network can become serious barriers that hinder access to quality mental health care. Some studies describe this rigidity as a lack of flexibility in the way services are provided. This includes the absence of treatment options adapted to the specific needs and characteristics of children and adolescents, the limited access to new or alternative treatments, and the existence of restrictive admission processes and criteria for accessing services (Appleton et al., 2021; Kantor et al., 2022; Platell et al., 2020, 2021). On this subject, various studies (Glowacki et al., 2022; Zifkin et al., 2021) report that these criteria involve the need for children and adolescents to obtain a particular score on the instruments used to assess levels of seriousness before being admitted or referred to the services. This means that those who do not have disorders with serious symptoms are refused access to these services (Appleton et al., 2021; Glowacki et al., 2022; Porras-Javier et al., 2018; Zarafshan et al., 2021). In a study where young Aboriginal people were interviewed was found that they would prefer the use of comprehensive detection tools and specific but flexible entry guidelines to make it easier to identify the illness and ensure that appropriate care would be provided (Kalucy et al., 2019).

As for the weakness of the referral network, two studies (Damian et al., 2018; Paton et al., 2021) see this as the absence of any clear structure for sending children to mental health specialists, hospital services, or emergency departments in situations of crisis. Another investigation carried out with parents and adolescents found that the pathways for seeking care and attention were complex and involved "going round in circles" from one medical institution to another, forcing users to frequently resort to emergency or other services before being sent to a specialist (Zifkin et al., 2021). This contributed to delays in treatment, led to long waiting lists and meant that opportunities for preventive interventions were missed (Damian et al., 2018; Delagneau et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Lambert et al., 2020; Meldahl et al., 2022; Paton et al., 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018; Son et al., 2019; Zarafshan et al., 2021). These studies indicate that a referral network and clear, effective planning must be included if children and young people are to receive specialist care when they need it.

Another of the barriers found in the literature concerns the logistical problems of existing services (Goodcase et al., 2021; Kalucy et al., 2019; Mathias et al., 2021; Platell et al., 2020, 2021; Son et al., 2019). This refers to the practical barriers that hinder the access to and continuity of care, including the rigid timetable of services outside school hours (Glowacki et al., 2022; Slotte et al., 2022), too much bureaucracy (Crouch et al., 2019; Herbell & Banks, 2020), an absence of resources in rural or geographically remote areas, or where the population is widely dispersed (Delagneau et al., 2020; Paton et al., 2021), a lack of transport and long journey times (Damian et al., 2018; Olcoń & Gulbas, 2018; Palinkas et al., 2021; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Porras-Javier et al., 2018) and the cost of the services (Kantor et al., 2022; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Paton et al., 2021). These problems are disproportionately worse in countries with low incomes, racial and ethnic minorities, and other vulnerable groups (Banks, 2022; Kretchy et al., 2021; Nhedzi et al., 2022; Majumder et al., 2018; Memiah et al., 2022; Park et al., 2022; Tulli et al., 2020; Zarafshan et al., 2021). As a solution, logistical difficulties could be overcome by introducing online or telehealth services (Paton & Hiscock, 2019). However, investigations that have analyzed teleconferencing services, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, have also come across barriers hampering access to the internet and technology (Banks, 2022; Palinkas et al., 2021). Mental health care system should be made more flexible and adaptable in order to meet the particular needs of children and young people, improve the range of options, increase the number of treatment centers, and close the gap between primary care and mental health care systems (Meldahl et al., 2022). This would have implications for professionals, system organizers, and researchers, who would need to include parents, children, and adolescents when planning, implementing, and assessing the services in order to satisfy their mental health needs (Majumder et al., 2018; Nhedzi et al., 2022; Platell et al., 2021; Wales et al., 2021).

Financial Resources

Apart from the rigidity and structural weaknesses of the systems, financial barriers were also found in the mental health care provided during childhood and adolescence. These were associated with the cost of care, insurance coverage, out-of-pocket expenses, and family financial structures.

The barriers impeding access (Kretchy et al., 2021; Mathias et al., 2021; Son et al., 2019) included the high cost involved, the lack of public coverage of services and the need to take on private insurance. As pointed out by a great number of studies (Goodcase et al., 2021; Herbell & Banks, 2020; Kalucy et al., 2019; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Radez et al., 2021; Park et al., 2022; Paton et al., 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018), some countries provide free or low-cost services through public coverage or government programs. Nevertheless, the general rule seems to be that mental health services are privatized regardless of a country’s level of income. This may be due to cuts in public spending on medical care (Kalucy et al., 2019; Park et al., 2022; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Paton et al., 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018), the growing demand for mental health care in childhood and adolescence, especially since COVID-19 (Banks, 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Palinkas et al., 2021), and the lack of sufficient public resources to meet mental health needs (Damian et al., 2018; Delagneau et al., 2020; Goodcase et al., 2021; Kantor et al., 2022; Slotte et al., 2022). The private sector enables faster and more efficient access to care and can be more flexible as regards opening times and types of treatment, which might be more attractive for parents and adolescents seeking help (Meldahl et al., 2022).

Despite the flexibility and range of private treatment options, the high cost of the services means that families have to take out insurance to optimize expenses. However, many have no medical insurance or have policies that provide insufficient coverage for mental health services. Even people who do have insurance may still have to deal with high copayment costs and deductibles and/or care limitations (Damian et al., 2018; Goodcase et al., 2021; Herbell & Banks, 2020; Lee et al., 2022; Palinkas et al., 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018). In Ireland, for example, parents of adolescents with eating disorders informed that in some cases the terms of the insurance cover limited the duration of the treatment, forcing them to reduce the number of appointments in order to keep the cost low (McArdle, 2019). Therefore becoming difficult to maintain lengthy treatments because of the funding. The insurance limitations can also involve the exclusion of certain treatments, restrictions on the type of providers that can be used, and barriers to coverage depending on the seriousness of the disorder (Herbell & Banks, 2020). In another study, interviewed adolescents were very doubtful about healthcare funding and were worried they might be surprised by a bill, even years after the end of their treatment (Leijdesdorf et al., 2021).

This insufficient insurance coverage together with the privatization of care may discourage families from seeking or continuing with care for their children, given the impossibility of affording the high out-of-pocket costs (Paton & Hiscock, 2019). As well as the copayments and non-refundable expenses associated with insurance (Banks, 2022; Damian et al., 2018; Herbell & Banks, 2020), these costs include alternative or continuing therapies (Cleverley et al., 2020; Delagneau et al., 2020; Kalucy et al., 2019; Meldahl et al., 2022), tests and specific treatments (Kantor et al., 2022; Paton et al., 2021), medication (Kretchy et al., 2021) and transport costs and travel time to reach the services (Damian et al., 2018; Mathias et al., 2021; Paton et al., 2021; Son et al., 2019). On top of these are the opportunity costs stemming from child and adolescent mental health care. Parents often have to take time off work and in some cases even lose their jobs and employment opportunities, and this makes their economic situation even worse because of direct costs and the decrease in family productivity (Goodcase et al., 2021; Kantor et al., 2022). This leads to family financial infrastructures that are unable to pay for services or insurance, making it impossible to access or continue the mental health treatment of thousands of children and adolescents (Banks, 2022; Damian et al., 2018; Delagneau et al., 2020; Hiscock et al., 2020; Kantor et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022; McArdle, 2019; Nhedzi et al., 2022; Palinkas et al., 2021; Son et al., 2019; Tulli et al., 2020). As for challenges, public funding of insurance and services would be needed to guarantee adequate universal access to quality pediatric mental health care (Memiah et al., 2022).

Attitudes to Treatment

One of the most frequently perceived challenges is the way society views mental health. Most of the studies analyzed in this review (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Arora & Persaud, 2020; Banks, 2022; Goodcase et al., 2021; Hiscock et al., 2020; Jon-Ubabuco & Champion, 2019; Kantor et al., 2022; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Loos et al., 2018; Majumder, 2019; Mathias et al., 2021; Memiah et al., 2022; Nhedzi et al., 2022; Park et al., 2022; Radez et al., 2021; Slotte et al., 2022; Tsamadou et al., 2021; Tulli et al., 2020; Zifkin et al., 2021) describe the existence of a culturally accepted notion that sees mental disorder as something shameful. This leads to the stigmatization and discrimination of those with mental health problems, and this acts as a barrier when it comes to seeking help and adequate access to care and treatment. As an illustration of this, the adolescents interviewed in an investigation said they found it difficult to express their feelings and were worried they would be considered negatively by their peers and adults due to the high levels of stigma associated with mental illness (Radez et al., 2021). Similarly, in another study, adolescents in emotional distress with suicidal thoughts were perceived by society as weak, mad, immature, or stupid, and they were therefore reluctant to seek help for fear of being judged or feeling ashamed (Arora & Persaud, 2020). In addition, research focusing on immigrant Latino youth uncovered the existence of a “culture of silence” in childhood, understood as a pattern of behavior whereby children internalize and repress their experiences of psychological anxiety for fear of being stigmatized or punished (Olcoń & Gulbas, 2018). Another study found fairly deep-rooted beliefs and concerns among young people who associated having symptoms of mental disease with being locked up in psychiatric hospitals or being socially isolated. They therefore did little to seek help in case this happened to them (Majumder, 2019).

It is clear from the investigations analyzed that the stigma affects not only children and adolescents with mental illness but also their families, the community in general, and the professionals and service providers themselves. In another study, the most typical attitudinal barriers found in parents included shame and guilt for having children with emotional and/or behavioral problems (Park et al., 2022). Society and care providers often tend to blame the parents for deficiencies in upbringing or a lack of attachment (Hiller et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021). As a result mental illness often remains hidden, a family secret, sidestepping any referral to services and trying to solve problems ‘in-house’ so as to avoid labels and finger-pointing (Mathias et al., 2021; Tulli et al., 2020).

These attitudes of rejection and shame on the part of the children, their families, and society in general contribute to making mental illness and other developmental disorders taboo. This gives rise to widespread ignorance about mental health and how to access services (Bjønness et al., 2022; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; McArdle, 2019; Slotte et al., 2022; Wales et al., 2021; Zifkin et al., 2021). Social stigma and lack of knowledge complicate the identification and early detection of symptoms and behaviors associated with autism spectrum (ASD) and other disorders in children (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Jon-Ubabuco & Champion, 2019). This lack of knowledge leads to the late recognition and acceptance of this illness, forcing those involved to seek help only when the problems have worsened (Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Mathias et al., 2021; Slotte et al., 2022). Information campaigns in schools and the community aimed at reducing the stigma and increasing mental health literacy among the general public could empower professionals, adolescents and families to take the appropriate measures and seek help when the symptoms of illness appear (Zifkin et al., 2021).

Another barrier linked to the stigma and ignorance surrounding mental illness is the misattribution of illness in children and adolescents. A study carried out in New Zealand with parents of Korean immigrant children found that they tended to believe that their children’s behavioral and emotional problems were normal (Park et al., 2022). Sometimes it was the professionals who played down young people’s suicidal thoughts or mental health symptoms, invalidating their emotions and preventing them from expressing and processing them instead of repressing or denying them (Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Slotte et al., 2022). This happens especially with children and adolescents in care, where distress is seen as normal and associated simply with a lack of attachment or the experiences of past traumas (Damian et al., 2018; Hiller et al., 2020; Kantor et al., 2022). Various studies found that young people were afraid they would not be taken seriously by the services and did not seek help so as not to find out the severity of their condition (Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Kantor et al., 2022). This notion of playing down distress prevents people from seeking help, leads to services being underused, and generates distrust of the providers of care and treatment (Banks, 2022; Kantor et al., 2022). All this contributes to the search for non-medical alternatives and the use of traditional healing methods for problems considered psychological (Olcoń & Gulbas, 2018; Park et al., 2022; Zarafshan et al., 2021). These barriers are even greater in certain collectives that are subject to other prejudices, such as those directed towards people of a particular ethnic group, religion, age, disability, gender, or sexual orientation (Goodcase et al., 2021). Indeed, another study showed that children caught up in the child welfare system felt doubly rejected and stigmatized (Kantor et al., 2022).

Professional Intervention

Mental health in childhood and adolescence covers a wide range of disorders, symptoms, and behaviors that affect the well-being of children and adolescents. Various studies stress the complexity of mental disorders at these ages, bearing in mind that they include attention deficit disorder (Newlove-Delgado et al., 2018; Zarafshan et al., 2021), autism spectrum (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020), eating disorders (Herbell & Banks, 2020; Lockertsen et al., 2021; McArdle, 2019; Wales et al., 2021), addictions (Glowacki et al., 2022) and other mental and behavioral problems such as mood disorders and anxiety (Cleverley et al., 2020; Crouch et al., 2019; Hiscock et al., 2020; Radez et al., 2021). To these, it can be added the comorbidity with other situations of vulnerability such as infant abandonment (Kantor et al., 2022), migration (Olcoń & Gulbas, 2018; Park et al., 2022; Tulli et al., 2020), refuge (Damian et al., 2018; Majumder, 2019; Majumder et al., 2018; Tulli et al., 2020), dual diagnosis (Son et al., 2019) and other complex needs (Appleton et al., 2021; Frogley et al., 2019; Hiller et al., 2020; Paton & Hiscock, 2019). Given this degree of complexity, most studies point to barriers and challenges in connection with professional intervention which limit the quality and the quantity of the care.

First, the lack of training and professional specialization of mental health care providers is seen as a barrier in most of the studies (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Arora & Persaud, 2020; Banks, 2022; Damian et al., 2018; Hiller et al., 2020; Kalucy et al., 2019; Kretchy et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2020; Son et al., 2019; Palinkas et al., 2021; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Paton et al., 2021; Zarafshan et al., 2021). This refers to the fact that there is an absence or lack of the knowledge and relevant professional skills needed to diagnose, understand, and treat the mental health needs of children and adolescents and the possible comorbidities. The lack of training is perceived in all the agents involved, from GPs, pediatricians, pharmacists, and nurses up to the actual professional specialists in children’s mental health. Several studies state that there is a widespread lack of professional training and specialization, little familiarization with the services, limited clarity of professional roles, and insufficient training in the use of detection instruments among all the professionals involved (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Kretchy et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2020). Another research reports that GPs received no special training in child mental health but gained the knowledge they had through self-study and experience (Zarafshan et al., 2021). These studies recommended that any such training should include skills in interviewing and communicating with children and stressed the need for closer collaboration with schools and specialist CAMH services.

The shortage and instability of labor is also seen as a challenge in the analyzed literature (Damian et al., 2018; Goodcase et al., 2021; Herbell & Banks, 2020; Hiscock et al., 2020; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Lockertsen et al., 2021; McArdle, 2019; Meldahl et al., 2022; Memiah et al., 2022; Platell et al., 2020, 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018). This is due to the lack of funding for taking on and retaining professional resources and the creation of precarious contracts. Also, professionals working in CAMH are paid less than all other health professionals, which would make a career in this area less attractive (Paton et al., 2021). Stress and exhaustion among workers due to the high workload, lack of training, and the complexity of mental disorders at these ages lead to a high staff turnover (Herbell & Banks, 2020; Hiscock et al., 2020; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Lockertsen et al., 2021; Memiah et al., 2022; Paton et al., 2021; Platell et al., 2020). In addition to this instability, the high demand contributes to the excessive caseload, saturation of services, and breaks in treatment, preventing providers from understanding patients’ circumstances and carrying out timely diagnoses and effective interventions (Porras-Javier et al., 2018). In this respect, various studies (Hiscock et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Nhedzi et al., 2022; McArdle, 2019; Son et al., 2019; Tsamadou et al., 2021; Tulli et al., 2020; Wales et al, 2021; Zifkin et al., 2021) describe how parents and adolescents felt that they were not listened to and that it was difficult to establish a good therapeutic relationship and a warm atmosphere between all the agents involved. Safeguarding the continuity of care has thus become a challenge because otherwise access and adequate treatment would be more difficult to obtain, thereby aggravating CAMH, creating feelings of desperation and uncertainty in families, and causing people to mistrust the services (Hiscock et al., 2020; McArdle, 2019; Platell et al., 2020; Van den Steene et al., 2019; Zarafshan et al., 2021).

Another of the barriers identified was the lack of collaboration and coordination between care providers (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Bjønness et al., 2022; Damian et al., 2018; Goodcase et al., 2021; McArdle, 2019; Memiah et al., 2022; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Paton et al., 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018; Zifkin et al., 2021). Mental health care is often provided in a fragmented setting, which makes it difficult to coordinate care and communication between mental health service providers and other professionals and systems (Goodcase et al., 2021; Platell et al., 2020; Porras-Javier et al., 2018; Zifkin et al., 2021). According to various studies, the absence of universal protocols and clear referral guidelines generate inconsistencies in practice and hamper real collaboration between professionals (Hiller et al., 2020; Paton et al., 2021). In addition, in many cases, it is the parents themselves that must coordinate the health services and it is stressful for them to handle communications and the exchange of information between hospital professionals, the outpatient department, the GP, school, and work (Bjønness et al., 2022). These barriers make early detection difficult and can result in inadequate or ineffective treatment and a lack of follow-up and support (Damian et al., 2018; McArdle, 2019; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Zifkin et al., 2021). Given these limitations, improving coordination and communication between services and systems could provide valuable information and maximize the chances of success of any mental health treatment (Goodcase et al., 2021).

Apart from all these barriers, the studies also showed that there was cultural hostility in care settings. Parents and young people of different cultural origins said they felt discriminated against or marginalized in the care process because of their race, ethnic group, religion, sexual orientation, or language (Arora & Persaud, 2020; Banks, 2022; Goodcase et al., 2021; Kalucy et al., 2019; Majumder et al., 2018; Meldahl et al., 2022). Cultural differences need to be understood in order to understand the distress peculiar to children and adolescents and decide on the treatment (Olcoń & Gulbas, 2018). In particular, the conception of mental health, body language, and the expression of emotions can have different meanings in different cultures. A lack of understanding or cultural sensitivity on the professionals' side can make it difficult to determine the best diagnosis and treatment (Majumder et al., 2018). A study in a New Zealand setting noted that Korean parents generally distrusted the dominant Western systems as regards cultural competence and were skeptical about the professionals’ ability to understand the underlying cultural problems (Park et al., 2022). Another study concluded that health services should be sensitive and receptive to adolescents’ cultural backgrounds so as to adequately meet their individual mental health needs (Meldahl et al., 2022). For this to be possible there would need to be culturally competent professionals and translators to ensure respect for cultural identity (Arora & Persaud, 2020; Banks, 2022; Kalucy et al., 2019; Majumder et al., 2018).

Shortcomings of the Biomedical Model

The literature points out the predominance and maintenance of the biomedical model and the barriers associated with mental health care for children and adolescents. This paradigm tackles illness from a reductionist point of view, focusing mainly on the biological causal factors and aiming to relieve symptoms as a form of treatment without taking into account each person’s social aspects, personal history, culture, or subjective experience (Kretchy et al., 2021). One study reveals a pessimistic picture of the care system characterized by a lack of humanity, attention, and empathy based on the paternalism and authoritarianism of the care providers (Loos et al., 2018). In particular, the participants in this study describe the attitude of the professionals as indifferent, obedient to the system, uninterested in individual cases with their unique histories and needs, and with a rigid vision that stigmatizes and classifies people according to their clinical diagnosis. This dehumanization may manifest itself as a lack of time and resources aimed at personalized care and limited availability of community resources and therapies that respect the autonomy and individual needs of children and adolescents (Damian et al., 2018; Glowacki et al., 2022; Goodcase et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2020; Meldahl et al., 2022; Platell et al., 2020).

One of the consequences of the biomedical model, as denounced by various studies (Goodcase et al., 2021; Kantor et al., 2022; Kretchy et al., 2021; Majumder et al., 2018; Porras-Javier et al., 2018; Zarafshan et al., 2021; Zifkin et al., 2021), is the trend towards an excessive prescription of psychiatric or psychotropic medication as a quick solution to illness, without taking into account unwanted secondary effects or the root of the problem. This is aggravated by the exclusion of children, adolescents and parents from any decision-making about their treatment and care planning, thereby restricting their participation in the process and making it hard for them to feel involved or committed (Appleton et al., 2021; Bjønness et al., 2022; Cleverley et al., 2020; Lockertsen et al., 2021; Majumder, 2019; Meldahl et al., 2022; Nhedzi et al., 2022; Palinkas et al., 2021; Platell et al., 2021; Slotte et al., 2022; Tsamadou et al., 2021; Wales et al., 2021).

The lack of effort made in the area of prevention is another challenge facing the mental health systems of children and adolescents. Biomedical care that focuses on treating the symptoms of the illness and the provision and maintenance of inadequate resources limit the development of preventive measures at all levels. In the analyzed studies, the perception is that actions and strategies need to be developed in order to promote mental health (Nhedzi et al., 2022; Putkuri et al., 2022; Son et al., 2019), avoid the development of illness (primary prevention) (Arora & Persaud, 2020; Damian et al., 2018; Frogley et al., 2019; Memiah et al., 2022; Palinkas et al., 2021; Putkuri et al., 2022; Zifkin et al., 2021), and reduce the impact of existing disorders through early detection and intervention (secondary prevention) (Al Maskari et al., 2020; Hiscock et al., 2020; Kalucy et al., 2019; Kretchy et al., 2021; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Park et al., 2022). Various authors (Arora & Persaud, 2020; Mathias et al., 2021; Putkuri et al., 2022) stress the fundamental role of schools as agents of prevention and gateways to child mental health services. To this end, the education system needs to be equipped with the necessary mechanisms and training, that includes free and accessible psychosocial care in schools and universities (Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Putkuri et al., 2022; Radez et al., 2021). The absence of preventive measures also implies the need to develop and implement comprehensive detection tools that take into account the etiology and complexity of mental health in childhood and adolescence (Frogley et al., 2019; Kalucy et al., 2019; Memiah et al., 2022).

Another challenge stemming from the biomedical model and the lack of specialist care in CAMH services is long waiting lists and short consultation times (Appleton et al., 2021; Crouch et al., 2019; Damian et al., 2018; Delagneau et al., 2020; Glowacki et al., 2022; Herbell & Banks, 2020; Hiller et al., 2020; Leijdesdorf et al., 2021; Meldahl et al., 2022; Son et al., 2019; Paton et al., 2021; Platell et al., 2020, 2021; Porras-Javier et al., 2018; Zarafshan et al., 2021; Zifkin et al., 2021). Many adolescents wait between 6 and 12 months for their first appointment (Meldahl et al., 2022). This causes treatment delays and a loss of opportunities for preventive interventions, forcing young people to use emergency services in serious cases (Appleton et al., 2021; Paton et al., 2021; Zifkin et al., 2021). In the same investigation (Zifkin et al., 2021), parents reported that the short consultation time meant that their children’s initial psychiatric assessment took place under pressure, leaving mental health needs unmet.

The transition from child mental health care to adult services stood out as the most complicated area and requires special attention and adequate planning. The studies that analyzed the barriers associated with this stage (Appleton et al., 2021; Cleverley et al., 2020; Glowacki et al., 2022; Lockertsen et al., 2021; Loos et al., 2018; Newlove-Delgado et al., 2018; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Son et al., 2019; Wales et al, 2021) explained that the change from CAMH to AMH services also involved a break in care that causes an even greater risk that young people might lose access to the services. Reaching the age of 18 often brings a sudden break in CAMH care, with all support being withdrawn (Appleton et al., 2021; Wales et al., 2021). This generates uncertainty and distress and makes those affected feel they are unready for change and autonomy. Among the limitations found, the literature warns that the change in providers generates problems with medication and a loss of trust and continuity in the professional relationship (Appleton et al., 2021; Cleverley et al., 2020; Lockertsen et al., 2021; Newlove-Delgado et al., 2018; Wales et al, 2021). In addition to this, problems involving communication between the services with long waiting times for referral were found, having to revisit painful or traumatic histories, limitations in continuity, and even rejection of care (Appleton et al., 2021; Glowacki et al., 2022; Lockertsen et al., 2021; Son et al., 2019).

These challenges demonstrate the lack of integrated and multidisciplinary care (encompassing mental, physical, and social care) in healthcare systems, which are unable to provide coordinated and holistic interventions and services to address mental health needs (Frogley et al., 2019; Glowacki et al., 2022; Goodcase et al., 2021; Paton & Hiscock, 2019; Putkuri et al., 2022). The persistence of the biomedical model hinders the management and delivery of health services on a continuous basis across all levels of care, from promotion and prevention to diagnosis, treatment, and recovery in CAMH (Nhedzi et al., 2022; Son et al., 2019).

Discussion

Previous research has documented the presence of challenges and barriers in mental health systems for children and adolescents worldwide. However, the literature continues to call for research that highlights trends, barriers and facilitators in the use of CAMHS in different contexts in order to create extensive and effective mental health resources and provide adequate care. In this sense, the problem has not been fully and comprehensively defined and identified, and a deeper and more critical analysis of the object of study is needed to identify less visible or more complex barriers, or the factors underlying them. To this end, it is paramount to understand more about the subjective perceptions and experiences of all individuals who personally or professionally navigate CAMH systems of care. This systematic review examined the available qualitative literature and identified full and extensive evidence of the many structural, financial, attitudinal, and treatment barriers that limit the quality of life and well-being of children and adolescents with mental health needs. These barriers are the result of a double discrimination rooted in all social structures, including the universal and institutional stigma surrounding mental illness, and the trivialization of the needs and experiences of children and adolescents. Despite efforts made by the WHO and the recommendations for closing the gaps in mental health care found in the literature, the findings show the immaturity of mental health systems and their inability to achieve the quality indicators established by institutional organizations in terms of funding, provision, service portfolio, and governance. The results demonstrate that, if adult mental health care is neglected, child and adolescent mental health is an invisible and neglected drawer of the health care system.

The 51 qualitative studies which were examined showed that the mental health treatment gap is universal, and concerns for its study is steadily increasing. Previous studies have reported that CAMH represents an increasing morbidity burden, especially in those territories that lack the means to deal with it, i.e. LMICs (Ceccarelli et al., 2022; Juengsiragulwit, 2015). Results show that the problem should be extrapolated to other countries, regardless of income levels. The scientific literature over recent years has seen a global increase in research into barriers and challenges in this area, especially in HMICs. More and more countries are adopting a critical approach in the analysis of health systems, believing it to be a research priority for political action on CAMH. Such growth in the scientific corpus coincides with an increase in the prevalence of these disorders, especially since COVID-19 (Holmes et al., 2020; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2022). The pandemic created a situation in which CAMH services not only had to adapt at unprecedented speed to satisfy increasing demand but at the same time had to deal with the system’s pre-existing overload and shortcomings (Huang & Ougrin, 2021).

Data analysis has identified the presence of many systemic or structural shortcomings and limitations of institutional policies and procedures that restrict children and adolescents with mental health needs from accessing services and receiving adequate treatment. These challenges involve different dimensions, such as accessibility of services and information, physical and geographic availability, affordability and related costs, and suitability and acceptability of CAMH services (Kourgiantakis et al., 2023). On this subject, most investigations mentioned insufficient funding and the lack of resources as the main challenges to access. Thus the lack of public support of mental health care leads to more privatization of services, generating incalculable and unacceptable costs for families. In confluence with another study, carried out with an adult population, this is mainly due to unwillingness or lack of commitment on the part of governments that aggravates the mental health treatment gap (Carbonell et al., 2020). This highlights the need to design policies to prioritize mental health in childhood and adolescence, with public investment in prevention programs, accessible and sustainable treatment services, and support for families (WHO, 2013).

In line with previous research, this investigation also finds significant barriers in professional intervention, including lack of training among staff, shortage and instability of labor, the absence of coordination between professionals and services, and cultural hostility (O’Brien et al., 2016). Results suggest that there are no common standards or requirements governing qualifications and training that are recognized in all countries (Barrett et al., 2020). The literature recommends that training should not just specifically cover CAMH, but also include practical communication skills along with cultural and social competence to enable people to effectively tackle the complexity of disorders at these ages. In addition, training should be provided for all professionals who deal with children and adolescents, including psychiatrists, GPs, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and teachers (Tarín-Cayuela, 2022). This would allow them to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to detect, assess and intervene from their respective areas of specialization and action. This supports existing research that points out that the deployment of a highly qualified workforce backed by an adequate allocation of professional resources would make it possible to reduce the workload and stabilize the professional workforce, thereby providing comprehensive, specialized, individualized, quality CAMH care (Findling & Stepanova, 2018). This study calls for the need to achieve recognition of CAMH as a specialty in its own right within health care services, taking into account its complexity and the cultural differences and specific needs in each context.

Like those of other investigations, the findings of the present study suggest that the stigma associated with mental illness is very deep-rooted in all social structures and is a basic obstacle to the implementation of public policies aimed at ensuring the welfare of people with such conditions (Beers & Joshi, 2020). Also, the presence of phenomena that have received little attention in the scientific literature on mental health, e.g. the infantilization, normalization and silence associated with childhood and adolescence, has been noted. Such attitudes associate emotional distress and mental health with being an intrinsic and inevitable part of these stages of life, but this underestimates the real needs and hinders early detection and the implementation of effective interventions. The taboo and resulting widespread ignorance surrounding mental health and how to access services make it difficult to seek and access help (Werner-Seidler et al., 2017). In this respect the CAMH treatment gap is simply a reflection of the historical unfairness with which mental health has been treated by the political agenda compared to other illnesses, which perpetuates the systematic lack of mental health protection for children and adolescents (Patel et al., 2018). Added to these barriers are the stigmas associated with other children and adolescents in situations of particular vulnerability, including migrants and refugees, those affected by poverty or disability and those in the youth justice system or in care (Fante-Coleman & Jackson-Best, 2020; Rice & Harris, 2021), all of whom require specialized therapeutic care. This syndemic of interaction between stigmas increases the continuum of conditions of vulnerability for these collectives, multiplying the risks and gaps in care and intervention, and restricting the development of suitable public policies to guarantee the rights and emotional wellbeing of children and adolescents with complex needs. As a result it is clear that stigma needs to be dealt with by promoting greater awareness and understanding of CAMH and providing appropriate, competent and accessible mental health professionals and services for these ages. To this end, interventions to reduce public and self-stigma are useful (Waqas et al., 2020), but their long-term effectiveness will be limited if institutional stigma is not addressed in mental health structures and policies.

In line with other research, the complexity of the disorders and the absence of public resources have resulted in mental health for children and adolescents becoming a hodgepodge of uncoordinated services with neither appropriate nor permanent specialized care (Benedet, 2011). The legacy and maintenance of the biomedical and pharmaceutical care model continue to result in the dehumanization of care, in which emotional and psychosocial aspects are often neglected or medicated. This review contributes to evidence that the barriers and challenges are rooted in the health system itself, and stem from the historical supremacy of physical health and the universal lack of understanding and acceptance of mental health, especially at younger ages. These findings are consistent with the postulation that the disdain for mental health limits any efforts made in the direction of prevention and early detection, aggravating symptoms or causing them to become chronic when they could be dealt with through appropriate intervention (Carbonell & Navarro-Pérez, 2019). This in turn has led to the construction of a mental health “subsystem” characterized by time-restricted consultations, long waiting lists, low specialization, discontinuity of care, limited availability of community resources and specific therapies, and excessive medication as the main solution. This gap is aggravated in the transition to adult life, where growing up turns into a new healthcare abyss (Appleton et al., 2022).

Implications for Research, Policy and Practice

The identification and definition of challenges and barriers in mental health care systems for children and adolescents are fundamental for the formulation of appropriate public policies that will ensure the development of effective services and interventions in the future. The results highlight the need to urgently address these identified deficiencies, in order to establish a realistic foundation for the planning and implementation of effective policies and programs. Additionally, gathering experiences from all stakeholders involved in CAMHS has encouraged a rigorous, comprehensive, and shared diagnosis that facilitates progress in the field of child mental health and help decision-making in improving interventions and services. In this regard, there is a need to move away from traditional paternalism y disdain associated with mental health and childhood and restore the voice to the consumers who exist within a fragmented and politicized healthcare system, placing citizens as co-producers of future policies that will create better-adapted systems for the real needs of CAMH. Active participation of adolescents in the evaluation of policies and services is required through qualitative methods that give them a voice and allow them to express their concerns and recommendations.

In the same way, the barriers and challenges found show how systems are unable to provide integrated, comprehensive, quality mental health care to children, adolescents, and young people of transition age. This review provides evidence of the need to invest in community programs and services to promote and educate about mental health, psychosocial support, early detection, and timely intervention. This means strengthening mental health care systems in terms of infrastructure, qualified professionals, accessible services, and safe, healthy settings. To overcome the gaps in mental health it is essential for there to be a change of model, moving the focus towards recovery, with support from policy-makers and a global framework. Reforms need to be implemented urgently to tackle the challenges identified in this study, with the aim of ensuring effective, continuing quality care, concentrating on the specific needs of children and adolescents. It is essential to take into account the peculiarities of these crucial stages of development and provide a comprehensive approach to promote mental and emotional well-being. Given deficiencies in care, studies have pointed out that schools are now being seen as a vital component of the mental health system (Hoover & Bostic, 2021). Teachers and school counselors can play a crucial role in early detection and the provision of suitable support. Nevertheless, it is essential that qualified support services and mental health care should be integrated into the community, in schools, for example, which would act as gateways to CAMH services. These services would need to cover the promotion, prevention, early intervention, and treatment of mental health with the aim of improving academic and psychosocial performance and reducing future consequences. What is needed is therefore the implementation of programs promoting mental health in the community in order to boost mental health, strengthen resilience, foster socioemotional skills, and provide tools for managing emotional distress. A solid and effective support network would thus be established in the socio-educational setting that would ensure care and the universality of provisions and treatment. A research priority study in CAMH is required to identify critical areas that have a significant impact on the well-being of children and adolescents, and subsequently prioritize them based on their urgency and relevance.

Despite these implications, it is worth noting that the results show that, without a critical and realistic approach to CAMH intervention and research that focuses on the structural causes of the system, all efforts made could be unsuccessful. Addressing the complexity and shortcomings of the mental health system requires a combination of public education, awareness raising, critical research, realistic policy advocacy, and social pressure in order to drive effective and sustainable long-term change. To do this, it is necessary to evaluate policies from a three-fold perspective (practical, political, and scientific) to determine their contribution to collective well-being and to make necessary adjustments, and to strengthen actions that promote growth and enhance the quality of life for the citizens. Further research is needed to establish specific evidence-based solutions and analyze the limitations to the continued implementation of interventions already in place in many countries. This will allow the cycle of policy development to continue.

Limitations of the Study

This review is not free of limitations. To begin with, the keywords and databases used may have omitted relevant information necessary for a truly exhaustive search. Additionally, publication bias may be another limitation. This means that the evidence available in peer-reviewed journals could tend towards research with positive results and therefore might not accurately reflect the whole body of research evidence that exists.

Four other limitations were found that could not be dealt with in the study. First, most of the studies cited were from high and upper-middle-income countries. This could be because of (1) the use of the concept “health system,” given that many countries lack an organized set of resources, institutions, professionals, and measures aimed at providing care; and (2) the biased scientific and publication system that may limit the production and publication of studies developed in LMIC due to language, interest, or quality issues. Second, the literature lacks a wide critical perspective regarding over-medicalization in child and adolescent mental health. Third, despite the fact that this review provides a general understanding of the barriers involved in the transition from CAMH to AMH services, more research is needed to look more specifically at the peculiarities, barriers, and challenges of the transition to adult life. Fourth, although it is true that there are a great many studies on COVID-19, social distancing measures, and their effect on mental health and suicide, the results of the present review only consider the challenges to children's mental health during this period when they have a direct bearing on the subject, mainly involving the measures adopted such as telehealth and attendance by video conference. So far no studies have been found that show how general health systems were able to be adapted and restructured flexibly and extremely quickly in response to the pandemic, while in the area of mental health, the system remained rigid. This may be because the mental health pandemic is not perceived as a real, tangible problem that calls for urgent changes. More studies are needed to address these gaps.

Conclusion

Scientific evidence on the shortcomings of the CAMH system is often examined in a partial or superficial manner, often based on quantitative data, which makes it difficult to fully understand the phenomenon. This systematic review captures and defines the hodgepodge reality of CAMH care and provides a comprehensive and critical understanding of the obstacles that children and adolescents face in accessing and receiving quality mental health services, from the perspective of all stakeholders. Systemic and structural barriers, limited financial resources, negative attitudes toward treatment, limitations in professional intervention, and deficits in the biomedical model are factors that influence access to and provision of mental health services. The nature of these limitations is universal and structural. Challenges and barriers in child and adolescent mental health care systems stem exclusively from traditional discrimination toward mental health, which is compounded by the downplaying of emotional distress at these ages. These findings underscore the urgent need for a comprehensive transformation and critical analysis of the system that promotes equity in access, specialized training, and greater coordination and integration of services, in order to ensure adequate care focused on the real needs of children and adolescents.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated during the current study.

References

References marked with asterisk refer to studies which were reviewed in detail and included in this systematic review.

Abidi, S. (2017). Paving the way to change for youth at the gap between child and adolescent and adult mental health services. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(6), 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717694166

Aguirre, A., Cruz, I. S. S., Billings, J., Jimenez, M., & Rowe, S. (2020). What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0

*Al Maskari, T., Melville, C., Al Farsi, Y., Wahid, R., & Willis, D. (2020). Qualitative exploration of the barriers to, and facilitators of, screening children for autism spectrum disorder in Oman. Early Child Development and Care, 190(11), 1762–1777. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1550084

Al-Adawi, S., Ganesh, A., Al-Harthi, L., Al-Saadoon, M., Al Sibani, N., & Eswaramangalam, A. (2023). Epidemiological and psychosocial correlates of cognitive, emotional, and social deficits among children and adolescents in Oman: A literature review. Child Indicators Research, 16(2), 689–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09988-4

*Appleton, R., Elahi, F., Tuomainen, H., Canaway, A., & Singh, S. P. (2021). “I’m just a long history of people rejecting referrals” experiences of young people who fell through the gap between child and adult mental health services. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(3), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01526-3

Appleton, R., Loew, J., & Mughal, F. (2022). Young people who have fallen through the mental health transition gap: A qualitative study on primary care support. British Journal of General Practice, 72(719), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2021.0678

*Arora, P. G. M., & Persaud, S. (2020). Suicide among Guyanese youth: Barriers to mental health help-seeking and recommendations for suicide prevention. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 8, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1578313

Babatunde, G. B., van Rensburg, A. J., Bhana, A., & Petersen, I. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to child and adolescent mental health services in low-and-middle-income countries: A scoping review. Global Social Welfare, 8, 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-019-00158-z

Baltag, V., & Servili, C. (2016). Adolescent mental health: New hope for a “Survive, Thrive and Transform” policy response. Journal of Public Mental Health, 15(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-12-2015-0054

*Banks, A. (2022). Black adolescent experiences with COVID-19 and mental health services utilization. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(4), 1097–1105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01049-w

Banwell, E., Humphrey, N., & Qualter, P. (2021). Delivering and implementing child and adolescent mental health training for mental health and allied professionals: A systematic review and qualitative meta-aggregation. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02530-0

Barrett, E., Jacobs, B., Klasen, H., Herguner, S., Agnafors, S., Banjac, V., Bezborodovs, N., Cini, E., Hamann, C., Huscsava, M. M., Kostadinova, M., Kramar, Y., Mandic, V., McGrath, J., Molteni, S., Moron-Nozaleda, G. M., Mudra, S., Nikolova, G., Pantelidou, K., Prata, A. T., Revet, A., … Hebebrand, J. (2020). The child and adolescent psychiatry: Study of training in Europe (CAP-STATE). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01416-3

Beers, N., & Joshi, S. V. (2020). Increasing access to mental health services through reduction of stigma. Pediatrics, 145(6), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0127

Bekhet, A. K., & Zauszniewski, J. A. (2012). Methodological triangulation: An approach to understanding data. Nurse Researcher, 20(2), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2012.11.20.2.40.c9442

Benedet, M. J. (2011). Los cajones desastre: De la neurologia, la neuropsicologia, la pediatria, la psicologia y la psiquiatria. CEPE: Ciencias de la Educacion Preescolar y Especial.

*Bjønness, S., Grønnestad, T., Johannessen, J. O., & Storm, M. (2022). Parents’ perspectives on user participation and shared decision-making in adolescents’ inpatient mental healthcare. Health Expectations, 25(3), 994–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13443

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

Carbonell, A., Georgieva, S., Navarro-Pérez, J. J., & Botija, M. (2023). From social rejection to welfare oblivion: Health and mental health in Juvenile Justice in Brazil, Colombia and Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115989

Carbonell, A., & Navarro-Pérez, J. J. (2019). The care crisis in Spain: An analysis of the family care situation in mental health from a professional psychosocial perspective. Social Work in Mental Health, 17(6), 743–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2019.1668904

Carbonell, A., Navarro-Pérez, J. J., & Mestre, M. V. (2020). Challenges and barriers in mental healthcare systems and their impact on the family: A systematic integrative review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 28(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12968

Ceccarelli, C., Prina, E., Muneghina, O., Jordans, M., Barker, E., Miller, K., Singh, R., Acarturk, C., Sorsdhal, K., Cuijpers, P., Lund, C., Barbui, C., & Purgato, M. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences and global mental health: Avenues to reduce the burden of child and adolescent mental disorders. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 31, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000580

Chindarkar, N., Ramesh, M., & Howlett, M. (2022). Designing social policies: Design spaces and capacity challenges. In B. G. Peters & G. Fontaine (Eds.), Research handbook of policy design (pp. 323–337). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839106606.00030

*Cleverley, K., Lenters, L., & McCann, E. (2020). “Objectively terrifying”: A qualitative study of youth’s experiences of transitions out of child and adolescent mental health services at age 18. BMC Psychiatry, 20, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02516-0

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (2003). Los conceptos y la codificación. In A. Coffey & P. Atkinson (Eds.), Encontrar el sentido a los datos cualitativos (pp. 31–63). Universidad Nacional de Antioquia.

Critical Appraisal Skills Program. (2023). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. CASP UK. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

*Crouch, L., Reardon, T., Farrington, A., Glover, F., & Creswell, C. (2019). “Just keep pushing”: Parents’ experiences of accessing child and adolescent mental health services for child anxiety problems. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(4), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12672

*Damian, A. J., Gallo, J. J., & Mendelson, T. (2018). Barriers and facilitators for access to mental health services by traumatized youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.01.003

De Voursney, D., & Huang, L. N. (2016). Meeting the mental health needs of children and youth through integrated care: A systems and policy perspective. Psychological Services, 13(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000045

*Delagneau, G., Bowden, S. C., Bryce, S., van-der-EL, K., Hamilton, M., Adams, S., Burgat, L., Killackey, E., Rickwood, D., & Allott, K. (2020). Thematic analysis of youth mental health providers’ perceptions of neuropsychological assessment services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12876

Elharake, J. A., Akbar, F., Malik, A. A., Gilliam, W., & Omer, S. B. (2022). Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college students: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54, 913–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1

Fante-Coleman, T., & Jackson-Best, F. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare in Canada for Black youth: A scoping review. Adolescent Research Review, 5(2), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-020-00133-2