Abstract

Evidence-based information is essential for effective mental health care, yet the extent and accessibility of the scientific literature are critical barriers for professionals and policymakers. To map the necessities and make validated resources accessible, we undertook a systematic review of scientific evidence on child and adolescent mental health in Greece encompassing three research topics: prevalence estimates, assessment instruments, and interventions. We searched Pubmed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and IATPOTEK from inception to December 16th, 2021. We included studies assessing the prevalence of conditions, reporting data on assessment tools, and experimental interventions. For each area, manuals informed data extraction and the methodological quality were ascertained using validated tools. This review was registered in protocols.io [68583]. We included 104 studies reporting 533 prevalence estimates, 223 studies informing data on 261 assessment instruments, and 34 intervention studies. We report the prevalence of conditions according to regions within the country. A repository of locally validated instruments and their psychometrics was compiled. An overview of interventions provided data on their effectiveness. The outcomes are made available in an interactive resource online [https://rpubs.com/camhi/sysrev_table]. Scientific evidence on child and adolescent mental health in Greece has now been cataloged and appraised. This timely and accessible compendium of up-to-date evidence offers valuable resources for clinical practice and policymaking in Greece and may encourage similar assessments in other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence-based information is pivotal to the planning and delivery of effective mental health care [1]. Prevalence surveys can identify frequent mental health conditions, assessing priorities of care and revealing at-risk groups. A pool of locally validated measurement instruments is key to mental health research and practice, as it allows professionals to screen, assess, and monitor conditions in accordance with the best practices of measurement-based care [2]. Empirical evidence on interventions informs strategies for effective allocations of resources. However, scientific literature is scattered and costly to assess, creating a ubiquitous barrier to evidence-based health delivery [3,4,5,6]. Thus, moving science into action requires that evidence is available in a timely manner and has been synthesized and appraised according to well-established evidence-based principles.

Mental health services in Greece underwent a substantial modernization throughout the last few decades, including the implementation of child and adolescent specialized services and the development of a sectorized system [7, 8]. Nevertheless, a series of challenges remain for child and adolescent mental health care, mainly stemming from a lack of funding that was aggravated by the economic crisis [9]. For instance, although policies pertaining to the sectorization of child and adolescent services were established [10], less than half of the planned services were created or implemented [11]. There is still a shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists in the public sector [12, 13], particularly in rural areas, as the majority of staff are located in the urban centers [14]. Moreover, there are substantial gaps in epidemiological knowledge on mental health issues for the Greek general population [15], and mental health care provision has been understudied [16].

The “Child and Adolescent Mental Health Initiative” (CAMHI) project is a 5-year program that aims to enhance child and adolescent mental health care capacity and to help strengthen the infrastructure for the prevention, assessment, and treatment of mental health difficulties faced by children and adolescents across Greece. With the goal of facilitating the systematic uptake of evidence to inform policy and practice, we began this program by examining the scientific literature to map available resources and trace research priorities on child and adolescent mental health within the country. Herein, we report a comprehensive systematic review of the national scientific literature pertaining to child and adolescent mental health care in Greece. The review compiled, synthesized, and assessed prevalence surveys, validated assessment instruments, and interventions for mental health conditions among children and adolescents up to 18 years old. This accessible new compendium of up-to-date evidence-based information can offer valuable resources for both clinical practice and policymaking in Greece and may encourage the undertaking of similar assessments in other countries.

Methods

We followed the guidelines described by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [17]. The PRISMA checklist can be consulted in Supplementary Table 1. This study was registered in Protocols.io (number 68583) [18], a platform that allows for registration after initiation of data extraction. For having an exceptionally broad scope as a nation-based systematic review, we anticipated that data extraction tables would require ad hoc adaptations and could only be traced after an overview of the magnitude and characteristics of findings. Therefore, we registered the protocol during the data extraction phase, when we defined appropriate methods for summarizing results.

Search strategy

Aiming at a comprehensive assessment of the Greek literature, a multi-step search strategy was employed targeting several electronic databases from inception to December 16th, 2021, without restrictions of language. First, we searched Pubmed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO using English free terms that associate mental health conditions, children and adolescents, and Greece (see Supplementary Table 2 for the full queries). Then, we searched IATPOTEK database using corresponding Greek terms, aiming to reach local peer-reviewed literature. Duplicates were automatically removed using the software EPPI-Reviewer 4.0 [19]. As a complementary step, we searched Google Scholar using English and Greek terms. This is a crawler-based search engine that retrieves results that are exceedingly numerous to manage, and is recommended as an additional source of information for systematic reviews [20, 21]. Therefore, we used it to scan for studies that were not included in our primary set and as a source for gray literature. Two authors (AC, LEM) independently inspected results until reaching a mark of 100 sequential studies that did not contain any novel inclusion. We also examined the reference list of studies for snowballing inclusions and consulted local experts for additional references. All studies were uploaded to and managed with Rayyan [22], a platform designed to organize systematic reviews.

Areas of systematic review

This review covers three research areas: prevalence estimates, assessment instruments, and interventions. Initially, we conducted an umbrella search to retrieve a set of studies that were screened and classified into those three research areas. Then, we carried out a three-arm review process, with distinct extraction and synthesis strategies for each topic.

Inclusion criteria

Prevalence studies

We included studies reporting surveys on community-based, school-based, or other representative samples assessing the prevalence (lifetime, 12 months, and point prevalence) of mental health conditions (ascertained by clinical or structured interviews using ICD or DSM coding, or indicated by validated cutoffs on screening instruments) or the levels of mental health symptoms or of mental well-being/quality of life (using standardized instruments) among children and adolescents up to 18 years old in Greece.

Multi-country studies were included if data for Greek participants were separately presented. If the same dataset was reported in more than one study, we only included the most comprehensive or most recent manuscript. We included literature reviews for reference consulting purposes, and dissertation thesis, academic letters, and book chapters were eligible.

We excluded surveys on clinical settings (e.g., quality of life among leukemia patients) or non-representative samples (prevalence of conditions of very specific populations, such as survivors of earthquakes or other traumatic events). We also excluded conference abstracts.

Instrument studies

We included studies that developed, translated, validated, or solely applied instruments of screening, clinical assessment, or diagnosis of child and adolescent (up to 18 years old) mental health outcomes in Greece, regardless of the nature of the sample. Instruments developed for the adult or general population were included if the study applied it to our targeted population.

Multi-country studies were included if data for Greek participants were available. If an instrument was reported in more than one study, they were both included whenever presenting different information (e.g., distinct properties of psychometric validation). If two studies reported the same property (e.g., two internal consistency analyses), only the most powered study (i.e., highest sample size) was included. Literature reviews were included for reference consulting purposes. Dissertation thesis, academic letters, and book chapters were eligible if inclusion criteria were met. We excluded conference papers.

Intervention studies

We included studies reporting interventions for mental health conditions or for mental health promotion, including mental well-being/quality of life, targeting children and adolescents (up to 18 years old) in Greece. Any interventional design was eligible, from pre–post uncontrolled studies to randomized clinical trials. We also planned to include studies that aimed to translate or adapt interventions that proved effective in other settings, even without testing their effectiveness.

Multi-country studies were included if data for Greek participants were available. If two studies reported on the same trial, only the most recent one was included. Literature reviews were included for reference consulting purposes. Dissertation thesis, academic letters, and book chapters were eligible. We excluded papers on interventions that also included the adult population without discriminating data between age groups. In addition, we excluded conference abstracts.

Screening process

During primary screening, two authors (AC, LEM) independently assessed results from databases searched with English terms. For databases searched with Greek terms, only one reviewer assessed the studies (VK). Studies were sorted into three areas of interest, and a specific study could be included in more than one area.

In the secondary screening, a single reviewer assessed full-text articles for final inclusion and extraction in each area (AC for prevalence studies, LEM for intervention and instrument studies). Any question of inclusion of a specific study was reviewed within the research team. Cross-group inclusions were allowed in this phase (for instance, if a study previously classified in the instrument area presented relevant information on prevalence).

Data extraction and synthesis

Prevalence studies

We followed and adapted the extraction procedures of a systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of child and adolescent mental health conditions [23]. The following data were extracted: first author, year of publication, study description, region of which the study attempts to be representative, year of data collection, description of sampling/representativeness, age range, sex or gender distribution, details of screening and diagnostic sample procedures (screening sample size, screening response rate, screening instrument, screening informant, method for screening selection, diagnostic sample size, diagnostic response rate), diagnostic domain, condition or construct, assessment instrument, if instrument includes interview, informants, diagnostic criteria, if diagnosis requires functional impairment, definition of functional impairment, prevalence estimate and its standard deviation (SD) or 95% confidence interval (CI), and mean score and its standard deviation (SD). We evaluated risk of bias with a validated quality assessment tool for prevalence studies covering external validity, internal validity, analysis bias, and representativeness of the sample [24]. Next, a summary table was derived to concisely present information. Finally, we created a synthesis table for aggregating information for each condition, including its lowest and highest prevalence estimate. In this table, only conditions with prevalence rates were included, as quality of life and other constructs counted only on mean scores obtained via assessment instruments. Due to the clinical heterogeneity across the studies, we did not perform a meta-analysis of prevalence estimates.

Instrument studies

We followed the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) guidelines for creating data extraction sheets and for evaluating the strengths of findings and their methodological quality [25]. All psychometric terms employed hereby are in accordance with the definition provided in the manual. Whenever an aspect of data extraction was not contemplated in the consensus instructions, we adapted a strategy for extraction after consulting scientific literature on the area.

The first section of the extraction protocol covered general information of the studies and instruments (first author, year of publication, name of the instrument, diagnostic domain, construct evaluated, original language, target population, informer/rater, recall period, number of items, response options, estimated time of application), sample description (sample size, age mean/range, percentage of females, diagnosed conditions, setting, response rate), and interpretability (proposed cutoff, percentage of missing items, floor and ceiling effects).

In the following section, we extracted information on study sampling and analytical procedures. First, a multi-choice field described study objectives (development, translation, validation, translation and validation, or application of an instrument). For studies on instrument translation, we included a checkbox to determine whether a back-and-forth translation procedure was undertaken. For instrument development studies, we ascertained the risk of bias of the items “development quality” and “content validity quality” in accordance with instructions of the manual. For studies that reported psychometric validation procedures (structural validity, internal consistency, cross-cultural validity, inter-rater reliability, test–retest reliability, measurement error, criterion validity, construct validity, or responsiveness), we also followed the manual and extracted three fields for each property: sample size for that procedure, methodological quality (very good, adequate, doubtful, inadequate, or not applicable), and results (see Supplementary Table 3 for detailed extraction procedures).

Next, we derived a summary table to concisely present information on the psychometric properties of each instrument and study. Therein, we compiled data on instrument translation or development and a set of psychometric properties according to the manual coding: “ + ”, for sufficient; “−”, for insufficient; and “?”, for indeterminate. This rating followed COSMIN’s criteria, except for translation/development (see Supplementary Table 4) and responsiveness (see Supplementary Table 5). Finally, we created a synthesis table for aggregating the information on each instrument, rating psychometric properties as sufficient (“ + ”) whenever it was ascertained as such in at least one study.

Intervention studies

For building an extraction table, we followed and adapted the suggested extraction table of the Cochrane manual for systematic reviews of intervention studies [26]. For each intervention study, the following data were extracted: first author, year of publication, sample size, experimental intervention, control intervention, diagnostic domain, target construct/disorder, primary outcome, primary outcome measurement, secondary outcome, secondary outcome measurement, sample description, age range/mean, percentage of females, ethnicity, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, recruitment method, allocation method, unit of allocation (individuals, clusters), duration of intervention, number of participants randomized by treatment arm, withdrawals and exclusions, other treatments received, subgroups, time points measured, person measuring/reporting, main results, funding, and conflicts of interest. Whenever possible, we calculated controlled and uncontrolled Cohen’s d effect sizes using reported means and standard deviations before and after the intervention using the command “escalc” from the package “meta” in the software R version 3.6.2 [27]. We evaluated methodological quality of studies through the revised version of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [28]. For non-randomized designs, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist assessment tool [29]. Next, a summary table was derived to concisely present information.

Results

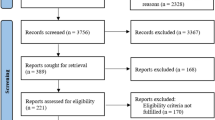

A total of 4476 abstracts were retrieved in the umbrella search in Pubmed, Embase, PsyciNFO, and IATPOTEK databases, and another 1,074 were screened from Google Scholar. After de-duplication and full-text analysis, this yielded 102 publications in prevalence studies, 16 in instrument studies, and 27 in intervention studies. Reference list, expert consultation, and cross-group inclusions led to a further 2 inclusions in the prevalence domain, 207 in the instruments domain, and 7 in interventions. A final number of 104 prevalence studies, 223 instruments studies, and 34 intervention studies were included in the review. Figure 1 details the screening procedures and Supplementary Table 6 summarizes reasons for exclusion.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize representative results for prevalence estimates and assessment tools, respectively. Table 3 describes intervention studies. A free interactive dataset to navigate all findings across different levels of information is available online [https://rpubs.com/camhi/sysrev_table/]. The extraction table, summary table, synthesis table, and risk of bias assessment for each area are fully available in Supplementary File 1.

Figure 2 displays the number of studies in each research topic according to diagnostic domains, representing areas of concentration of scientific production. In this sense, general psychopathology was the domain counting on the most number of articles, as 17 prevalence studies reported data on constructs such as internalizing symptoms and emotional functioning, and another 34 instrument studies reported instruments that assess symptoms from multiple domains or general constructs. Next, a significant focus of scientific papers was neurodevelopment, with 3 studies on prevalence estimates, 47 on assessment tools, and 1 on experimental interventions. This is followed by anxiety disorders, quality of life, substance use disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders, to name a few. Domains such as violence and neglect, sleep disorders, and obsessive compulsive disorders counted on very few reports across all research areas. No reports were found for domains such as bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders.

Prevalence studies

A total of 104 studies reported 533 estimates of the prevalence of mental health conditions, levels of mental health symptoms, or levels of quality of life/well-being. Most studies used scale cutoff points to ascertain the presence/absence of a mental health condition, which can greatly overestimate prevalence in comparison to gold-standard assessments such as clinical interviews. Only four estimates relied on clinical diagnosis or structured interviews. Most studies had their methodological quality rated as good, with some considered very good and a few presenting quality concerns. Tobacco use was the most commonly reported prevalence estimate, with 15 studies pointing to rates of regular smoking from 5.4 to 38.1% in samples aged 12–18 years of varying regions of the country (Crete, Ioannina, Karlovasi, Kos, Thessaloniki, nationwide). The prevalence for Internet addiction disorder was reported in eight studies, rates ranging from 0.8% to 16.1% in samples from 12 to 18 years old surveyed between 2007 and 2012. Another frequently reported condition was attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and estimates from four studies point to prevalence rates from 2.6% to 6.5% in samples aged 6–11 years old surveyed using instruments rated by caregivers or teachers. For depressive disorder, three studies pointed to estimates from 5.7 to 30.5% in samples from 10 to 18 years old, with the last survey taking place in 2008. Autism spectrum disorder estimates were available in two studies, reporting prevalence from 1.15 to 10.1% in samples aged 6–11 years, which were obtained using caregiver-rated screening tools and also clinical diagnosis. There were no prevalence estimates for diagnosis such as generalized anxiety disorder or psychotic disorders, but one study reported a prevalence of 42.3% for anxiety symptoms in a 9- to 12-year-old sample from the Athens—Piraeus area. Studies were mostly concentrated in the regions of Attica, Crete, and Thessaloniki.

Instrument studies

A total of 223 studies reported information on 261 instruments that measure mental health outcomes. Specific domains with the highest number of available instruments were: neurodevelopment (52 instruments), general psychopathology (28 tools classified as broadband mental health instruments or measuring general constructs), anxiety disorders (17 instruments), and autism spectrum disorders (13 instruments). There was a scarcity of instruments for the domains of substance use, child abuse, and psychotic disorders. The most studied instrument was the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), with information reported on five positively rated psychometric properties taken from five studies. The majority of instruments were translated from their original English version using a validated back-and-forth procedure, and 48 measurement tools were reported to be originally developed in Greek. Psychometric properties like internal consistency were considered sufficient and counted on adequate methodological quality for most studies, while others such as cross-cultural validity, criterion validity, and measurement error were seldom reported or had significant risk of bias. Most studies had psychometric validation of some, but not most, properties.

Intervention studies

A total of 34 studies reported different interventions conducted in clinical trials. Most frequently, they evaluated psychosocial group interventions (e.g., anti-stigma programs at a school, anti-smoking education, problem-solving skills, psychoeducational programs), but there were also a few individual or mixed interventions, one pharmacological therapy (a formulation with compounds from the Sophora japonica for adaptive behavior in autism), and one dietary intervention (ketogenic diet for autism spectrum disorder). Twelve studies applied uncontrolled before–after designs, 13 studies used quasi-experimental designs, and 9 studies were randomized clinical trials. The risk of bias for all studies was rated as high. There were no studies that aimed to validate interventions that proved effective in other settings.

Discussion

This is a comprehensive systematic review of the scientific literature on the mental health of children and adolescents in Greece, which compiled and assessed studies reporting prevalence estimates, instrument assessment tools, and intervention trials. We compiled data on 533 prevalence estimates or level of symptoms for over 79 conditions or constructs in varying regions from Greece, mapped resources of 261 locally validated assessment tools, and provided an overall picture of 34 interventions reported in clinical trials in the country. This landscape analysis revealed prevalent conditions according to localities and uncovered conditions for which data are lacking, as well as regions that have not been sufficiently contemplated by research. It also provided a map of locally validated instruments, alongside their characteristics and psychometric properties. Finally, the landscape analysis brought together a set of locally studied interventions, revealing data on their effectiveness, methodological strengths, and weaknesses, and elucidated needed directions for upcoming research.

This work can be understood within the framework of implementation science, as it aims to address the well-documented gap between research and mental health practice [30]. A pivotal step in addressing this challenge is to make scientific data easily available and appraised according to evidence-based principles, as real-world scenarios require up-to-date and accessible information for decision-making. This review provides such a compendium of data and information about available tools and estimates, which can readily inform professionals, policymakers, and other stakeholders in the fields of mental health assistance and research. Using the freely available interactive tool we have created to navigate this data, mental health practitioners and researchers can consult these resources to find locally validated instruments that most suit their needs in both research and clinical settings, with options to filter it according to psychometrics, informants, or age group. Policymakers could also turn to this dataset for validated guidance when planning mental health programs, as the prevalence estimates of mental health conditions indicate targets for interventions, helping to establish priorities for care and to guide the allocation of resources. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first initiative to undertake a comprehensive national review and assessment of the literature on child and adolescent mental health.

This systematic review has many strengths. It has a broad scope with a comprehensive search strategy, including a range of databases, snowballing inclusions, and expert consultation, without restrictions of time or language. It also follows appropriate evidence synthesis guidelines for the three domains (i.e., prevalence estimates, assessment instruments, and interventions), rigorously inspecting studies according to manuals such as the Cochrane, COSMIN, or established evidence-based practices. Furthermore, it synthesizes a significant amount of results in an accessible manner for consultation.

Throughout the process, we also encountered a number of limitations. As an overall issue, we could not a priori define the best data synthesis strategy, which could only be traced after visualization of data extraction, delaying protocol registration up to this point. Most studies retrieved in the search were published in English or had English abstracts, and were independently screened by two assessors. A minority of data entries, which were exclusively published in Greek and retrieved from IAPOTEK and Google Scholar searches, were screened by a single author. In the instruments area, the review scope is particularly challenging, since many translations and validations exist in sources that may not be captured by our search strategy (books, conferences, manuals, or developer websites). We tried to address this by extensively consulting the reference list from studies and taking recommendations from experts in the area, which accounted for a significant number of inclusions that outnumbered the inclusions from our primary dataset.

In conclusion, this landscape analysis can serve as a critical tool in bridging the gap between research and practice in Greece, as clinicians and policymakers can easily access tools and data to inform their practice and priorities, and which may serve to encourage similar nationwide studies beyond Greece.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. No new data were collected for this work.

References

Wainberg ML, Scorza P, Shultz JM et al (2017) Challenges and opportunities in global mental health: a research-to-practice perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19:28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0780-z

Parikh A, Fristad MA, Axelson D, Krishna R (2020) Evidence base for measurement-based care in child and adolescent psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 29:587–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2020.06.001

Kavic MS, Satava RM (2021) Scientific literature and evaluation metrics: impact factor, usage metrics, and altmetrics. JSLS. https://doi.org/10.4293/JSLS.2021.00010

DiBartola SP, Hinchcliff KW (2017) Metrics and the Scientific Literature: Deciding What to Read. J Vet Intern Med 31:629–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.14732

Vinny PW, Vishnu VY, Lal V (2016) Trends in scientific publishing: Dark clouds loom large. J Neurol Sci 363:119–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.02.040

Vinkers CH, Lamberink HJ, Tijdink JK et al (2021) The methodological quality of 176,620 randomized controlled trials published between 1966 and 2018 reveals a positive trend but also an urgent need for improvement. PLoS Biol 19:e3001162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001162

Madianos MG (2020) The adventures of psychiatric reform in Greece: 1999–2019. BJPsych Int 17:26–28. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2019.30

Giannakopoulos G, Anagnostopoulos DC (2016) Psychiatric reform in Greece: an overview. BJPsych Bull 40:326–328. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.116.053652

Kolaitis G, Giannakopoulos G (2015) Greek financial crisis and child mental health. Lancet 386:335. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61402-7

Christodoulou G, Ploumpidis D, Christodoulou N, Anagnostopoulos D (2010) Mental health profile of Greece. Int Psychiatry 7:64–67

Anagnostopoulos DC, Soumaki E (2013) The state of child and adolescent psychiatry in Greece during the international financial crisis: a brief report. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22:131–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0377-y

Christodoulou NG, Kollias K (2019) Current challenges for psychiatry in Greece. BJPsych Int 16:60–61. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2018.23

Christodoulou GN, Ploumpidis DN, Christodoulou NG, Anagnostopoulos DC (2012) The state of psychiatry in Greece. Int Rev Psychiatry 24:301–306. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.691874

Anargyros KP, Christodoulou NG, Lappas AS (2021) Community mental health services in Greece: development, challenges and future directions. Consortium Psychiatricum 2:61–66

Paleologou MP, Anagnostopoulos DC, Lazaratou H et al (2018) Adolescents’ mental health during the financial crisis in Greece: the first epidemiological data. Psychiatrike 29:271–274. https://doi.org/10.22365/jpsych.2018.293.271

Stierman EK, Kalbarczyk A, Oo HNL et al (2021) Assessing barriers to effective coverage of health services for adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. J Adolesc Health 69:541–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.12.135

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Marchionatti LE, Komoula A, Caye A, et al (2022) Protocol for a nationwide systematic review of the Greek literature on child and adolescent mental health v1. Protocols.io

Thomas, Brunton, Graziosi (2010) EPPI-Reviewer 4.0: software for research synthesis. EPPI-Centre Software London

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR (2020) Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res Synth Methods 11:181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S (2015) The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 10:e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5:210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS et al (2015) Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56:345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A et al (2012) Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 65:934–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM et al (2018) COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 27:1147–1157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (2019) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://wwwR-project.org/. Accessed 30 Sept 2022

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898

Aromataris E, Stern C, Lockwood C et al (2022) JBI series paper 2: tailored evidence synthesis approaches are required to answer diverse questions: a pragmatic evidence synthesis toolkit from JBI. J Clin Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.04.006

Shelton RC, Lee M, Brotzman LE et al (2020) What is dissemination and implementation science?: an introduction and opportunities to advance behavioral medicine and public health globally. Int J Behav Med 27:3–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09848-x

Mellon RC, Moutavelis AG (2007) Structure, developmental course, and correlates of children’s anxiety disorder-related behavior in a Hellenic community sample. J Anxiety Disord 21:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.008

Skounti M, Philalithis A, Mpitzaraki K et al (2007) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in schoolchildren in Crete. Acta Paediatr 95:658–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02312.x

Skounti M, Giannoukas S, Dimitriou E et al (2010) Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in schoolchildren in Athens, Greece. Association of ADHD subtypes with social and academic impairment. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2:127–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-010-0029-8

Papaioannou S, Mouzaki A, Sideridis GD et al (2016) Cognitive and academic abilities associated with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a comparison between subtypes in a Greek non-clinical sample. Educ Psychol Rev 36:138–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.915931

Alemany S, Avella-García C, Liew Z et al (2021) Prenatal and postnatal exposure to acetaminophen in relation to autism spectrum and attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms in childhood: meta-analysis in six European population-based cohorts. Eur J Epidemiol 36:993–1004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00754-4

Thomaidis L, Mavroeidi N, Richardson C et al (2020) Autism spectrum disorders in greece: nationwide prevalence in 10–11 year-old children and regional disparities. J Clin Med Res 9:2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072163

Koutra K, Kritsotakis G, Orfanos P et al (2014) Social capital and regular alcohol use and binge drinking in adolescence: a cross-sectional study in Greece. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 21:299–309. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2014.899994

Analitis F, Velderman MK, Ravens-Sieberer U et al (2009) Being bullied: associated factors in children and adolescents 8 to 18 years old in 11 European countries. Pediatrics 123:569–577. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0323

Serdari A, Gkouliama A, Tripsianis G et al (2018) Bullying and minorities in secondary school students in Thrace-Greece. Am J Orthopsychiatry 88:462–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000281

Chudal R, Tiiri E, Brunstein Klomek A et al (2022) Victimization by traditional bullying and cyberbullying and the combination of these among adolescents in 13 European and Asian countries. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:1391–1404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01779-6

Madianos MG, Gefou-Madianou D, Stefanis CN (1993) Depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior among general population adolescents and young adults across Greece. Eur Psychiatry 8:139–146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0924933800001929

Kleftaras G, Didaskalou E (2006) Incidence and teachers’ perceived causation of depression in primary school children in Greece. Sch Psychol Int 27:296–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306067284

Magklara K, Bellos S, Niakas D et al (2015) Depression in late adolescence: a cross-sectional study in senior high schools in Greece. BMC Psychiatry 15:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0584-9

Siomos KE, Dafouli ED, Braimiotis DA et al (2008) Internet addiction among Greek adolescent students. Cyberpsychol Behav 11:653–657. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0088

Thiakos K-I, Thoύka A-S (2010) Ethismos sto thiathikteo, ereena sten. Ellatha

Fisoun V, Floros G, Geroukalis D et al (2012) Internet addiction in the island of Hippocrates: the associations between internet abuse and adolescent off-line behaviours. Child Adolesc Ment Health 17:37–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00605.x

Trioda-Kyparissi A, Evagelou E (2011) Teenage internet addiction on the island of chios. Acta Paediatr 100:100–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02488.x

Tsitsika A, Critselis E, Janikian M et al (2011) Association between internet gambling and problematic internet use among adolescents. J Gambl Stud 27:389–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9223-z

Siomos K, Floros G, Fisoun V et al (2012) Evolution of Internet addiction in Greek adolescent students over a two-year period: the impact of parental bonding. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:211–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0254-0

Stavropoulos V, Alexandraki K, Motti-Stefanidi F (2013) Recognizing internet addiction: prevalence and relationship to academic achievement in adolescents enrolled in urban and rural Greek high schools. J Adolesc 36:565–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.008

Stavropoulos V, Griffiths MD, Burleigh TL (2018) Flow on the Internet: a longitudinal study of Internet addiction symptoms during adolescence. Behaviour 37:159–172

Lazaratou H, Dikeos DG, Anagnostopoulos DC et al (2005) Sleep problems in adolescence. A study of senior high school students in Greece. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 14:237–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-005-0460-0

Siomos KE, Avagianou P-A, Floros GD et al (2010) Psychosocial correlates of insomnia in an adolescent population. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 41:262–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-009-0166-5

Elisaf M, Papanikolaou N, Letzaris G, Siamopoulos KC (1996) Smoking habit in female students of northwestern Greece: relation to other cardiovascular risk factors. J R Soc Health 116:87–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/146642409611600205

Arvanitidou M, Tirodimos I, Kyriakidis I et al (2007) Decreasing prevalence of alcohol consumption among Greek adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 33:411–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990701315384

Farhat T, Simons-Morton BG, Kokkevi A et al (2012) Early Adolescent and Peer Drinking Homogeneity: Similarities and Differences Among European and North American Countries. J Early Adolesc 32:81–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431611419511

Garoufi A, Grammatikos EE, Kollias A et al (2017) Associations between obesity, adverse behavioral patterns and cardiovascular risk factors among adolescent inhabitants of a Greek island. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 30:445–454. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2016-0134

Kokkevi A, Nic Gabhainn S, Spyropoulou M, Risk Behaviour Focus Group of the HBSC (2006) Early initiation of cannabis use: a cross-national European perspective. J Adolesc Health 39:712–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.009

Kokkevi A, Fotiou A, Richardson C (2007) Drug use in the general population of Greece over the last 20 years: results from nationwide household surveys. Eur Addict Res 13:167–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000101553

Kokkevi A, Richardson C, Florescu S et al (2007) Psychosocial correlates of substance use in adolescence: a cross-national study in six European countries. Drug Alcohol Depend 86:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.018

Kokkevi A, Fotiou A, Kanavou E, et al (2016) Smoking, alcohol, and drug use among adolescents in Greece-2015 update and secular trends 1984–2015. Archives of Hellenic Medicine/Arheia Ellenikes Iatrikes 33

Kokkevi A, Stefanis C (1991) The epidemiology of licit and illicit substance use among high school students in Greece. Am J Public Health 81:48–52. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.81.1.48

Kokkevi A, Terzidou M, Politikou K, Stefanis C (2000) Substance use among high school students in Greece: outburst of illicit drug use in a society under change. Drug Alcohol Depend 58:181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00100-3

Francis K, Katsani G, Sotiropoulou X et al (2007) Cigarette smoking among Greek adolescents: behavior, attitudes, risk, and preventive factors. Subst Use Misuse 42:1323–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701212410

Kyrlesi A, Soteriades ES, Warren CW et al (2007) Tobacco use among students aged 13–15 years in Greece: the GYTS project. BMC Public Health 7:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-3

Arvanitidou M, Tirodimos I, Kyriakidis I et al (2008) Cigarette smoking among adolescents in Thessaloniki, Greece. Int J Public Health 53:204–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-008-8001-5

Heras P, Kritikos K, Hatzopoulos A et al (2008) Smoking among high school students. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 34:219–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990701877151

Lazuras L, Rodafinos A, Eiser JR (2011) Adolescents’ support for smoke-free public settings: the roles of social norms and beliefs about exposure to secondhand smoke. J Adolesc Health 49:70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.013

Giannakopoulos G, Tzavara C, Dimitrakaki C et al (2010) Emotional, behavioural problems and cigarette smoking in adolescence: findings of a Greek cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 10:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-57

Soteriades ES, Spanoudis G, Talias MA et al (2011) Children’s loss of autonomy over smoking: the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. Tob Control 20:201–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.036848

Kokkevi A, Richardson C, Olszewski D et al (2012) Multiple substance use and self-reported suicide attempts by adolescents in 16 European countries. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:443–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0276-7

Kokkevi A, Rotsika V, Arapaki A, Richardson C (2011) Increasing self-reported suicide attempts by adolescents in Greece between 1984 and 2007. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:231–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0185-3

Kokkevi A, Rotsika V, Botsis A et al (2014) Adolescents’ self-reported running away from home and suicide attempts during a period of economic recession in Greece. Child Youth Care Forum 43:691–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9260-3

Beratis S (1991) Suicide among adolescents in Greece. Br J Psychiatry 159:515–519. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.159.4.515

Zacharakis CA, Madianos MG, Papadimitriou GN, Stefanis CN (1998) Suicide in Greece 1980–1995: patterns and social factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33:471–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050081

Mittendorfer Rutz E, Wasserman D (2004) Trends in adolescent suicide mortality in the WHO European Region. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 13:321–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-004-0406-y

Bacopoulou F, Petridou E, Korpa TN et al (2015) External-cause mortality among adolescents and young adults in Greece over the millennium’s first decade 2000–09. J Public Health 37:70–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt115

Nikolaidis G, Petroulaki K, Zarokosta F et al (2018) Lifetime and past-year prevalence of children’s exposure to violence in 9 Balkan countries: the BECAN study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 12:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0208-x

Nicolaidou I, Stavrou E, Leonidou G (2021) Building primary-school children’s resilience through a web-based interactive learning environment: quasi-experimental pre-post study. JMIR Pediatr Parent 4:e27958. https://doi.org/10.2196/27958

Psychountaki M, Zervas Y, Karteroliotis K, Spielberger C (2003) Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the STAIC. Eur J Psychol Assess 19:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.19.2.124

Kalogiratou DS, Bacopoulou F, Kanaka-Gantenbein C et al (2020) Effects of the Pythagorean self awareness intervention on childhood emotional eating and psychological wellbeing: a pragmatic Trial. J Mol Biochem 9:13–21

Mourelatos E (2021) How personality affects reaction. A mental health behavioral insight review during the Pandemic. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02425-9

Emmanouil C, Bacopoulou F, Vlachakis D et al (2020) Validation of the Stress in Children (SiC) Questionnaire in a Sample of Greek Pupils. J Mol Biochem 9:74–79

Sofianopoulou K, Bacopoulou F, Vlachakis D et al (2021) Stress management in elementary school students: a pilot randomised controlled trial. EMBnet J. https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.26.1.976

Roussos A, Richardson C, Politikou K et al (1999) The Conners-28 teacher questionnaire in clinical and nonclinical samples of Greek children 6–12 years old. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 8:260–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870050100

Efstratopoulou M, Janssen R, Simons J (2012) Differentiating children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Conduct Disorder, Learning Disabilities and Autistic Spectrum Disorders by means of their motor behavior characteristics. Res Dev Disabil 33:196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.033

Efstratopoulou M, Janssen R, Simons J (2015) Assessing children at risk: psychometric properties of the motor behavior checklist. J Atten Disord 19:1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713484798

Efstratopoulou M, Simons J, Janssen R (2013) Concordance among physical educators’, teachers’, and parents’ perceptions of attention problems in children. J Atten Disord 17:437–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711431698

Papanikolaou K, Paliokosta E, Houliaras G et al (2009) Using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic for the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in a Greek sample with a wide range of intellectual abilities. J Autism Dev Disord 39:414–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0639-6

Zarokanellou V, Kolaitis G, Vlassopoulos M, Papanikolaou K (2017) Brief report: a pilot study of the validity and reliability of the Greek version of the Social Communication Questionnaire. Res Autism Spectr Disord 38:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2017.03.001

Giannakopoulos G, Kazantzi M, Dimitrakaki C et al (2009) Screening for children’s depression symptoms in Greece: the use of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a nation-wide school-based sample. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 18:485–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0005-z

Alexópoulos DA (2012) I antilípsis yia ti goneïkí tipoloyía kai o rólos tous stin anáptixi katathliptikís simptomatoloyías se paidiá proephivikís ilikías. University of Thessaly

Giannakopoulos G, Solantaus T, Tzavara C, Kolaitis G (2021) Mental health promotion and prevention interventions in families with parental depression: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 278:114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.070

Pliatskidou S, Samakouri M, Kalamara E et al (2015) Validity of the Greek Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire 6.0 (EDE-Q-6.0) among Greek adolescents. Psychiatrike 26:204–216

Pliatskidou S, Samakouri M, Kalamara E et al (2012) Reliability of the Greek version of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) in a sample of adolescent students. Psychiatrike 23:295–303

Kalogiratou DS, Bacopoulou F, Kanaka-Gantenbein C et al (2019) Greek validation of emotional eating scale for children and adolescents. J Mol Biochem 8:26–32

Motti-Stefanidi F, Tsiantis J, Richardson SC (1993) Epidemiology of behavioural and emotional problems of primary schoolchildren in Greece. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2:111–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02098866

Roussos A, Karantanos G, Richardson C et al (1999) Achenbach’s Child Behavior Checklist and Teachers’ Report Form in a normative sample of Greek children 6–12 years old. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 8:165–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870050125

Giannopoulou I, Dikaiakou A, Yule W (2006) Cognitive–behavioural group intervention for PTSD symptoms in children following the Athens 1999 earthquake: a pilot study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 11:543–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104506067876

Bibou-Nakou I, Markos A, Padeliadu S et al (2019) Multi-informant evaluation of students’ psychosocial status through SDQ in a national Greek sample. Child Youth Serv Rev 96:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.022

Duinhof EL, Lek KM, de Looze ME et al (2019) Revising the self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaire for cross-country comparisons of adolescent mental health problems: the SDQ-R. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 29:e35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000246

Giannakopoulos G, Tzavara C, Dimitrakaki C et al (2009) The factor structure of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in Greek adolescents. Ann Gen Psychiatry 8:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-8-20

Siomos KE, Floros GD, Mouzas OD, Angelopoulos NV (2009) Validation of adolescent computer addiction test in a Greek sample. Psychiatrike 20:222–232

Giannopoulou I, Smith P, Ecker C et al (2006) Factor structure of the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES) with children exposed to earthquake. Pers Individ Dif 40:1027–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.002

Tzavara C, Tzonou A, Zervas I et al (2012) Reliability and validity of the KIDSCREEN-52 health-related quality of life questionnaire in a Greek adolescent population. Ann Gen Psychiatry 11:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-11-3

Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L et al (2005) KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 5:353–364. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.5.3.353

Láppa A (2021) I mousikí agoyí kai i tekhnikés tis dramatikís tékhnis yia tin enískhisi tis epikinonías se paidiá me idikés anánges. Mia érevna drásis sto Idikó Skholío Aigáleo

Foka S, Hadfield K, Pluess M, Mareschal I (2021) Promoting well-being in refugee children: an exploratory controlled trial of a positive psychology intervention delivered in Greek refugee camps. Dev Psychopathol 33:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419001585

Sourvinos S, Mavropoulos A, Kasselimis DS et al (2021) Brief Report: speech and language therapy in children with ASD in an aquatic environment: the ASLT (Aquatic Speech and Language Therapy) Program. J Autism Dev Disord 51:1406–1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04629-7

Makrygianni MK, Gena A, Ree (2018) Real-world effectiveness of different early intervention programs for children with autism spectrum disorders in Greece. Int J Sch Educ Psychol 6:188–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2017.1302853

Koutsoura A (2017) Antimetopízontas ta arnitiká synaisthímata kai proothóntas ti synaisthimatikí ygeía ton mathíton: éna psychopedagogikó prógramma vasis̱méno stin praktikí tis sygchōritikótitas [PhD diss.]. University of Patras. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10889/11063

Hatzichristou C, Lianos P, Lampropoulou A (2017) Cultural construction of promoting resilience and positive school climate during economic crisis in Greek schools. Int J Sch Educ Psychol 5:192–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1276816

Vassilopoulos SP, Brouzos A, Andreou E (2015) A multi-session attribution modification program for children with aggressive behaviour: changes in attributions, emotional reaction estimates, and self-reported aggression. Behav Cogn Psychother 43:538–548. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465814000149

Vassilopoulos SP, Blackwell SE, Misailidi P et al (2014) The differential effects of written and spoken presentation for the modification of interpretation and judgmental bias in children. Behav Cogn Psychother 42:535–554. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465813000301

Χίου Β, Ζήση Α, Ξανθάκου Γ et al (2013) The implementation of the mental health promotion program “I Can Problem Solve” in public kindergarten schools in Greece: First year’s results. Psychol J Hellenic Psychol Soc 20(1):54–67. https://doi.org/10.12681/psy_hps.23519

Economou M, Peppou LE, Geroulanou K et al (2014) The influence of an anti-stigma intervention on adolescents’ attitudes to schizophrenia: a mixed methodology approach. Child Adolesc Ment Health 19:16–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00669.x

Makrygianni MK, Gena A, Reed P (2010) The effectiveness of behavioral and eclectic intervention programs for 6.5–14 years old children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders: a cross-cultural study. Teaching effectiveness. Nova Science Publishers, New York

Economou M, Louki E, Peppou LE et al (2012) Fighting psychiatric stigma in the classroom: the impact of an educational intervention on secondary school students’ attitudes to schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry 58:544–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011413678

Vassilopoulos SP, Banerjee R, Prantzalou C (2009) Experimental modification of interpretation bias in socially anxious children: Changes in interpretation, anticipated interpersonal anxiety, and social anxiety symptoms. Behav Res Ther 47:1085–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.018

Chryse H, Panayiota D, Konstantina L, Aikaterini L (2009) Promoting school community well-being: Implementation of a system-level intervention program. Psychology 16:379–399

Andreou E, Didaskalou E, Vlachou A (2007) Evaluating the effectiveness of a curriculum-based anti-bullying intervention program in greek primary schools. Educ Psychol Rev 27:693–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601159993

Zafiropoulou M, Thanou A (2007) Laying the foundations of well being: a creative psycho-educational program for young children. Psychol Rep 100:136–146. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.100.1.136-146

Tarnanas I, Manos G (2004) A clinical protocol for the development of a virtual reality behavioral training in disaster exposure and relief. Annu Rev Cyberther Telemed 2:71–83

Koumi I, Tsiantis J (2001) Smoking trends in adolescence: report on a Greek school-based, peer-led intervention aimed at prevention. Health Promot Int 16:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/16.1.65

Kotsopoulos SI, Karaivazoglou K, Florou IS et al (2021) Systematic intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder and integration in regular school classes: a naturalistic study. Glob Pediatr Health 8:2333794X211012988. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X211012988

Kouyioúri X (2021) Parémvasi áfxisis/enískhisis tis psikhikís anthektikótitas (resilience) se paidiá metakinoúmenon plithismón sti khóra ipodokhís. Athena European University

Fotiou A, Stavrou M, Papadakis S et al (2018) The TOBg tobacco treatment guidelines for adolescents: a real-world pilot study. Tob Prev Cessat 4:27. https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/93008

Giannopoulou I, Pasalari E, Korkoliakou P, Douzenis A (2019) Raising Autism Awareness among Greek Teachers. Int J Disabil Dev Educ 66:70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2018.1462474

Metropoύloe i (2015) Paithi kai ellenike oikonomike krise: psechoekpaitheetiko proyramma prolepses: ereena omathikes thiathikasias

Giannopoulou IG, Lardoutsou S, Kerasioti A (2014) Cbt parent training program for the management of young children with behavior problems: a pilot study. https://pseve.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Volume11_Issue3_Giannopoulou.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb 2023

Vassilopoulos SP, Brouzos A, Damer DE et al (2013) A psychoeducational school-based group intervention for socially anxious children. J Spec Group Work 38:307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2013.819953

Taliou A, Zintzaras E, Lykouras L, Francis K (2013) An open-label pilot study of a formulation containing the anti-inflammatory flavonoid luteolin and its effects on behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Ther 35(5):592–602

Evangeliou A, Vlachonikolis I, Mihailidou H et al (2003) Application of a ketogenic diet in children with autistic behavior: pilot study. J Child Neurol 18:113–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/08830738030180020501

Papavasiliou AS, Nikaina I, Rizou J, Alexandrou S (2011) The effect of a psycho-educational program on CARS scores and short sensory profile in autistic children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 15:338–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.02.004

Zafiropoulou M, Mati-Zissi H (2004) A cognitive–behavioral intervention program for students with special reading disabilities. Percept Mot Skills 98:587–593. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.98.2.587-593

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) for funding the SNF-CMI Child and Adolescent Mental Health Initiative and SNF’s Co-President Andreas C. Dracopoulos for his leadership in creating, launching, and supporting the project. We would also like to thank Ms. Elianna Konialis, Ms. Dimitra Moustaka, and Mr. Panos Papoulias for their critical role in multiple steps of the conceptualization and implementation of the SNF-CMI Child and Adolescent Mental Health Initiative. We also thank Samanta Duarte for designing the graphical representations included in this paper.

Funding

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation funded this study and their authors and had no role in the methodology, execution, analyses, or interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK, LEM, AC, PB, VEK, JLS, NPG, and GAS were responsible for conceptualizing, managing, and supervising the project. LEM, AC, PB, VEK, KL, VA, and NPG conducted the screening process and data extraction. AS built data presentation material. LEM, AC, NPG, JLS, VEK, and GAS analyzed the results. LEM wrote the main manuscript text. All other authors reviewed the manuscript and gave contributions and insights on data presentation and data visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AC has acted as a consultant for Knight Therapeutics in the past year. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koumoula, A., Marchionatti, L.E., Caye, A. et al. The science of child and adolescent mental health in Greece: a nationwide systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02213-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02213-9