Abstract

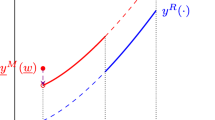

The literature on rent-seeking primarily focuses on contests for achieving gains, although contests for avoiding losses are also omnipresent. Examples for such ‘reverse’ contests are activities to prevent the close-down of a local school or the construction of a waste disposal close-by. While under standard preferences, investments in ‘reverse’ and ‘conventional’ contests should not be different, loss aversion predicts contests for avoiding losses to be fiercer than conventional ones. In our experimental data, the difference in investments between conventional and reverse Tullock contests is small and statistically insignificant. We discuss several explanations for this remarkable finding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We assume that if both players invest nothing, none of them wins the prize in the conventional contest.

To keep the contest rules symmetric, in the reverse contest, if no player invests, both receive the bad.

Chowdhury et al. (2017) present a model of loss aversion in contests that assumes the reference point to be the endowment minus the investment, i.e., wealth before the resolution of uncertainty. This model would make qualitatively similar predictions with respect to differences between conventional and reverse contests. We discuss further modeling assumptions of the reference points and their implications in Sect. 6.

Note that our simple model ignores other motives that have been shown to significantly influence investments in conventional Tullock contests towards overbidding such as joy of winning (see Sheremeta 2010, 2013). Kong (2008) studies the impact of loss aversion on behavior in conventional Tullock contests using individual measures. He finds that (a) more loss averse subjects invest less, which is in line with our theory, and that (b) subjects with all levels of loss aversion nevertheless overbid on average as compared to the loss neutral equilibrium. Following (b) we do not actually expect to observe underbidding as predicted by our model in any of the two contests. Our simple framework helps to formally derive predictions with respect to the direction of the effects tested in our study (under the ceteris paribus assumption).

We opted for a partner matching and against a stranger matching. In his meta-analysis on behavior in conventional Tullock contests, Sheremeta (2013) finds no statistically significant effect of the matching protocol on bidding behavior. Rockenbach and Waligora (2016a) replicate this finding in the subject pool of the current study (but with different subjects). Nevertheless, we are aware of Baik et al.’s (2015) study which finds less overbidding under partner matching for groups of two players. For the sake of an efficient experimental design, we opted for a partner matching.

As paying all rounds may induce wealth effects over time, we control for both time and accumulated wealth in our analyses.

The applied function is: \({ \hbox{max} }\{ 0; 4 - 0.4\left( {{\text{Belief}} - {\text{actual}} {\text{investment}}} \right)^{2} \}\). See Selten (1998) and Palfrey and Wang (2009) for the advantages of quadratic rules against linear ones. We are aware of the current discussion in the literature on whether and how to incentivize beliefs (e.g., Schlag et al. 2015). The elicitation of beliefs is a novel feature in experimental Tullock contests that we employ in several experiments within the scope of a larger research agenda. In the current paper, we do not focus on the influence of beliefs on behavior and refer the interested reader to the extensive discussion in Rockenbach and Waligora (2016b). We only shortly discuss beliefs in Sect. 6. Note that average beliefs do not significantly differ between our treatments and that when we include beliefs into regression (III) of Table 1 in Appendix A, the results do not change and there are no treatment differences with respect to the influence of beliefs on investments.

In our design, a pair of subjects over 20 periods constitutes one independent observation.

Instructions are available in the online appendix. All data and programs are available upon request.

Note that our partner matching might be at risk to provide some scope for collusion over time (although by our design, we eliminate the important focal point of zero bids, which increases the difficulty of collusive coordination). We re-run our analyses and exclude all observations in which the investments of both subjects in a pair in a given period are either zero, one or two. This conservative measure looks at every single act of every pair and not just at coordination over time and identifies 10.2% of observations in TC and 6.2% of observations in TR as possibly collusive acts, already suggesting that the incidence of collusion is low. When excluding those acts, all our results remain robust.

We find that the subjects’ beliefs closely follow their opponents’ lagged investment, i.e., they expect their opponent to invest just as much in the current round as in the previous round (r = 0.766 in TC and r = 0.795 in TR). In this sense, beliefs are myopic.

As a caveat, these two explanations similarly apply to Chowdhury et al.’s (2017) experiment and thus also suggest no treatment differences there. However, they find a large difference between conventional and reverse contests.

Other candidates for alternative reference points are earnings outside the experiment or the respective worst case scenario (investing a positive amount and still not winning the prize in TC or receiving the bad in TR, respectively). Both alternatives imply that all outcomes in the experiment are treated as gains and equilibrium predictions are similar to the loss neutral case. This is in contrast to experimental results by Kong (2008) who observes lower investments of subjects with higher loss aversion in conventional contests, in line with the theory outlined in Sect. 2.

In our post-experimental questionnaire, we elicited self-reported emotions (joy, happiness, surprise, irritation, regret, envy, and anger) after winning and losing the lottery as well as a measure of how important it was for subjects to win the lottery more often than the opponent, among other motives. We do not find any treatment differences in these variables and conclude that the non-monetary utility of winning is likely to be similar in TC and TR. Moreover, in the questionnaire, we asked subjects how important winning more often than their opponent was to them (measured on a 7-point Likert scale). Including the self-reported motive “winning more often” from the post-experimental questionnaire (as a proxy for non-observable joy of winning) in regression (III) in Appendix A yields a marginally significant positive coefficient (beta = 0.207, s.e. = 0.109), but an insignificant interaction term with TR (beta = 0.164, s.e. = 0.150).

References

Abbink, K., Brandts, J., Herrmann, B., & Orzen, H. (2010). Intergroup conflict and intra-group punishment in an experimental contest game. American Economic Review, 100(1), 420–447.

Ahn, T. K., Isaac, R. M., & Salmon, T. C. (2011). Rent seeking in groups. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 29(1), 116–125.

Amaldoss, W., & Rapoport, A. (2009). Excessive expenditures in two-stage contests: theory and experimental evidence. In I. N. Hangen & A. S. Nilsen (Eds.), Game Theory: Strategies, Equilibria and Theorems (pp. 241–266). NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Andreoni, J. (1995). Warm-glow versus cold-prickle: The effects of positive and negative framing on cooperation in experiments. Quarterly Journal of Economics, CX.1, 1–21.

Baik, K. H., Chowdhury, S. M., & Ramalingam, A. (2015). Group size and matching protocol in contests. CBESS Discussion Paper, 13-11R, 1–30.

Chowdhury, S. M., Jeon, J. Y., & Ramalingam, A. (2017). Property rights and loss aversion in contests. Economic Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12505.

Chowdhury, S., Sheremeta, R. M., & Turocy, T. L. (2014). Overbidding and overspreading in rent-seeking experiments: Cost structure and prize allocation rule. Games and Economic Behavior, 87, 224–238.

Congleton, R. D., Hillman, A. L., & Konrad, K. A. (2008). 40 years of Research on Rent Seeking (Vol. 1 and 2). Heidelberg: Springer.

Cornes, R., & Hartley, R. (2003). Loss aversion and the Tullock paradox. University of Nottingham Discussion Papers in Economics, 03(17), 1–25.

Cornes, R., & Hartley, R. (2012). Loss aversion in contests. The University of Manchester Economics Discussion Paper Series, EDP-1204, 1–27.

Dechenaux, E., Kovenock, D., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2015). A survey of experimental research on contests, all-pay auctions and tournaments. Experimental Economics, 18(4), 609–669.

Dutcher, E. G., Balafoutas, L., Lindner, F., Ryvkin, D., & Sutter, M. (2015). Strive to be first or avoid being last: An experiment on relative performance incentives. Games and Economic Behavior, 94, 39–56.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Goeree, J. K., Holt, C. H., & Palfrey, T. R. (2002). Quantal response equilibrium and overbidding in private-value auctions. Journal of Economic Theory, 104, 247–272.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1, 114–125.

Herrmann, B., & Orzen, H. (2008). The Appearance of homo rivalis: Social preferences and the nature of rent seeking. CeDEx Discussion Paper, No. 2008–10, 1–40.

Hong, F., Hossain, T., & List, J. A. (2015). Framing manipulations in contests: A natural field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 118, 372–382.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Kong, X. (2008). Loss aversion and rent-seeking: An experimental study. CeDEx Discussion Paper No., 2008–13, 1–32.

Masiliunas, A., Mengel, F., Reiss, J. P. (2014). Behavioral variation in Tullock contests. Working paper.

Palfrey, T. R., & Wang, S. W. (2009). On eliciting beliefs in strategic games. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 71, 98–109.

Parco, J. E., Rapoport, A., & Amaldoss, W. (2005). Two-stage contests with budget constraints: An experimental study. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 49, 320–338.

Rockenbach, B., Waligora, M. (2016a). On the reluctance to play best response in Tullock contests. Working Paper.

Rockenbach, B., Waligora, M. (2016b). Beliefs and behavior in Tullock contests. Working Paper.

Schlag, K. H., Tremewan, J., & van der Weele, J. J. (2015). A penny for your thoughts: a survey of methods for eliciting beliefs. Experimental Economics, 18(3), 457–490.

Schmitt, P., Shupp, R., Swope, K., & Cadigan, J. (2004). Multi-period rent-seeking contests with carryover: Theory and empirical evidence. Economic Governance, 5, 187–211.

Selten, R. (1998). Axiomatic foundation of the quadratic scoring rule. Experimental Economics, 62, 43–62.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2010). Experimental comparison of multi-stage and one-stage contests. Games and Economic Behavior, 68(2), 731–747.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2013). Overbidding and heterogeneous behavior in contest experiments. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27(3), 491–514.

Sonnemans, J., Schram, A., & Offerman, T. (1998). Public good provision and public bad prevention: The effect of framing. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 34, 143–161.

Szidarovsky, F., & Okuguchi, K. (1997). On the existence and uniqueness of pure Nash equilibrium in rent-seeking games. Games and Economic Behavior, 18, 135–140.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent-seeking. In J. Buchanan, R. Tollison, & G. Tullock (Eds.), Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society (pp. 97–112). Austin: Texas University Press.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) is gratefully acknowledged through FOR 1371. Sebastian Schneiders and Marcin Waligora thankfully acknowledge financial support by the Cologne Graduate School in Management, Economics and Social Sciences during their Ph.D. studies. We like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for helpful suggestions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rockenbach, B., Schneiders, S. & Waligora, M. Pushing the bad away: reverse Tullock contests. J Econ Sci Assoc 4, 73–85 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-018-0052-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-018-0052-7