Abstract

The scope of this work is to develop and optimize a reductive roasting process followed by wet magnetic separation for iron recovery from bauxite residue (BR). The aim of the roasting process is the transformation of the nonmagnetic iron phases found in BR (namely hematite and goethite), to magnetic ones such as magnetite, wüstite, and metallic iron. The magnetic iron phases in the roasting residue can be fractionated in a second stage through wet magnetic separation, forming a valuable iron concentrate and leaving a nonmagnetic residue containing rare earth elements among other constituents. The BR-roasting process has been modeled using a thermochemical software (FactSage 6.4) to define process temperature, Carbon/Bauxite Residue mass ratio (C/BR), retention time, and process atmosphere. Roasting process experiments with different ratios of C/BR (0.112 and 0.225) and temperatures (800 and 1100 °C), 4-h retention time, and, in the presence of N2 atmosphere, have proven almost the total conversion of hematite to iron magnetic phases (> 99 wt%). Subsequently, the magnetic separation process has been examined by means of a wet high-intensity magnetic separator, and the analyses have shown a marginal Fe enrichment in magnetic fraction in relation to the sinter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bauxite is an important ore that is widely used to produce metallurgical-grade alumina (the precursor for aluminum production) and chemical-grade alumina/aluminum hydroxide for many industrial applications through the Bayer process [1]. During this process, a byproduct is formed, known as bauxite residue (BR). The production of 1 ton of alumina generates between 0.9 and 1.5 ton of residue depending on the composition of initial bauxite ore [2, 3]; the handling of this byproduct is a major challenge for the alumina industry due to its high volume and high alkalinity [4, 5]. However, bauxite residue can be considered as a secondary raw material resource, due to the presence of valuable substances such us iron (Fe), titanium (Ti), aluminum (Al), and rare earth elements (REEs) [6, 7]. Indeed, in numerous studies, different processes have been developed to recover elements from BR [8, 9]. Concerning iron, it is present as oxides/oxyhydroxides, and usually it is the largest constituent in BR [7]. Techniques investigated for iron recovery from bauxite residue are mainly based on pyrometallurgical processes [10] where iron oxides are either reduced in the solid state followed by magnetic separation [11] or reduced by smelting in Electric Arc [12, 13] or other type of furnace [7, 14]. Although iron content in bauxite residue (14–45 wt%) is not as high as in average iron ores (60 wt%) used in the iron industry [7], the gradual depletion of available ores and the demand for sustainable industrial processing have encouraged technology development based on secondary raw materials with almost zero-waste production [15]. In this framework, iron recovery from bauxite residue has attracted major attention, as the iron recovered can be used as feedstock in the iron industry [11].

The aim of this research work is to develop an optimal process for reduction of hematite (Fe2O3) to magnetite (Fe3O4) in BR using a carbon source (metallurgical coke) as a reducing agent in a resistance-heated tube furnace; the reduction is investigated at conditions below the eutectic point of the Fe–C system to avoid formation of liquid phases. The target is to form liberated magnetic iron phases, allowing the magnetic separation of Fe content from the residue that will be enriched then in rare earths.

Experimental

Filter-pressed BR from MYTILINEOS S.A. was provided as starting material for this work. The material was first homogenized using a laboratory sampling procedure (riffling method), and then a representative sample was dried in a static furnace at 105 °C for 24 h. The particle size distribution of the dried sample was determined through laser particle size analysis in a Malvern Mastersizer™. The mean particle size (D50) of BR equals 1.87 μm.

Chemical analysis was performed via fusion method (1000 °C for 1 h with a mixture of Li2B4O7/KNO3 followed by direct dissolution in 6.5% v/v HNO3 solution) through inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), and atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS). The results (Table 1) have shown that BR contains 42.34 wt% of iron (in oxides form).

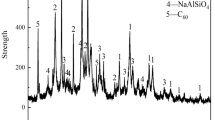

Mineralogical analysis of BR has been performed by X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) (Fig. 1) using a Bruker D8 Focus analyzer. The quantification of the mineral phases was carried out through a XDB database [16], which quantifies the amount of mineral phases via profile fitting. Iron mineralogical phases are shown in Table 2.

The presence of goethite was also confirmed through differential thermal analysis (DTA), using a SETARAM TG Labys-DS-C system in the temperature range of 25–1000 °C at a 10 °C/min heating rate, in air atmosphere.

As shown in Fig. 2, between 250 and 330 °C, a strong endothermic peak is present. This is correlated to the dehydroxylation of goethite to form hematite [17]. The other endothermic peaks disclosed in Fig. 2 are related to the dehydration of gibbsite (Al(OH)3) which partially overlapped the goethite peak around 280 °C, the dehydration of Ca3AlFe(SiO4)(OH)8 (200–300 °C), the dehydration of cancrinite (Na6Ca2(AlSiO4)6(CO3)2(H2O)2) between 400 and 625 °C, the dehydration of diaspore (AlOOH) at 500–550 °C, and the decarbonation of Na6Ca2(AlSiO4)6(CO3)2(H2O)2 at 750 °C [16].

Metallurgical coke was used as a reductant (Cfix = 80.31 wt%) in the roasting process which was carried out in an alumina tube furnace. Temperature in the furnace was measured using an R-type thermocouple. Several parameters were investigated to optimize the process, particularly furnace temperatures (between 400 and 1100 °C) and carbon-to-bauxite mass residue (C/BR) ratios (between 0.112 and 0.225), while time and pressure are kept constant at 4 h and 1 atm, respectively. In Fig. 3, a schematic diagram of the static tube furnace employed for the experiments is presented.

The optimized sinter was then passed through a Carpco™ Wet High Intensity Magnetic Separator (WHIMS) where an intense magnetic field is generated by two coils. An initial current intensity of 0.05 A was used, which resulted in the first magnetic fraction (Magnetic I, MAG I) and a residue, which is subsequently passed for a second time from the WHIMS. In the second pass, the current intensity was increased to 0.1 A, and a second magnetic fraction was collected (Magnetic II, MAG II). Magnetic I, Magnetic II, and Nonmagnetic fractions (residue from second pass, NM) were then dried and characterized. Figure 4 shows the details of the experimental procedure and process diagram.

Result and Discussion

Thermochemical Studies

The FactSage 6.4™ thermochemical software was used for the thermodynamic analysis of the reductive roasting of BR in presence of C. To examine the process, the modules FT-oxid, SG-TE, and FT-misc which contain all the oxides present in the system (including magnetite and wüstite), the metallic iron solution (pig iron), and the oxidic slag phase were employed.

The phase equilibrium diagram during the reductive roasting of pure hematite (under constant molar ratio C/(Fe + C) = 0.1 and 1 atm) as a function of process temperature and oxygen partial pressure in the system is shown in Fig. 5.

As was expected, the transformation of hematite to magnetite is drastically affected by the oxygen partial pressure in the system. The transformation temperature decreases as the oxygen partial pressure decreases reaching to a value lower than 500 °C in practically an oxygen-free reaction atmosphere (\( \log P_{{{\text{O}}_{2} }} = - 20 \)). The increase of process temperature under low oxygen partial pressures pushes gradually the system toward the formation of wüstite (FeO) and even of metallic iron at higher temperatures. The percentage compositions of the several mineralogical phases in the reductive roasting solid product as a function of temperature in practically an oxygen-free atmosphere with \( \log P_{{{\text{O}}_{2} }} = - 16 \), are shown in Fig. 6.

As seen in Fig. 6, the sintered products from the reductive roasting of hematite [(\( \log P_{{{\text{O}}_{2} }} = - 16 \), molar ratio C/(Fe + C) = 0.1, and Ptotal = 1 atm)] are exclusively composed of magnetite in the temperature range of 625–825 °C. The wüstite thermodynamic stability area is very narrow at the temperature range around 925 °C, while, at temperatures higher than 1000 °C, metallic iron is formed. Based on the performed thermodynamic analysis, the temperature regime between 400 and 1100 °C and an inert atmosphere were chosen as experimental parameters for the study of BR reductive roasting process.

Reductive Roasting of BR

Preliminary experiments were conducted to optimize the process. To evaluate the influence of temperature on the process, samples of 3.5 g possessing a metallurgical coke-to-bauxite residue mass ratio of 0.112, in the presence of N2 overpressure flow heated at a range of temperature between 400 and 1100 °C, were reduced.

Figure 7 shows that magnetite (Fe3O4) has already been formed at 800 °C as predicted by the thermochemical software. The transformation of hematite to magnetite has not been completed yet, as hematite still is the major mineralogical phase in the sinter.

To achieve the complete reduction of iron phases present in BR, several experiments, varying C/BR ratios ranging between 0.135 and 0.225, were performed. Time, pressure, and temperature were kept constant at 4 h, 1 atm, and 800 °C, respectively, under N2 atmosphere.

As shown in Fig. 8, the transformation of trivalent iron phases of Fe2O3 and Fe2O3·H2O into magnetic ones of Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 (maghemite) is favored with the increasing carbon/bauxite residue ratio. Examining the XRD profiles of different samples, Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 were the main iron mineralogical phases after 4 h of reductive roasting reaction at 800 °C, with C/BR ratio of 0.180. At the same time, under these conditions, all alumina-containing phases in BR (gibbsite, boehmite, diaspore, cancrinite, and calcium aluminates) have been transformed to corundum and gehlenite which is a calcium aluminosilicate phase not initially existing in BR. Titanium phases have been converted to perovskite and ilmenite. The calcite peak disappeared due to its thermal decomposition [17, 18]. The result of the roasting process optimization is the production of sinter with strong magnetic properties, containing Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 among the other constituents.

Magnetic Separation

Preliminary tests were performed to understand the magnetic behavior of tube furnace sinter (at 800 °C; C/BR = 0.180; 4 h roasting time, and in the presence of N2) using a wet high-intensity magnetic separator (WHIMS). Three fractions were collected: Magnetic I, Magnetic II, and Nonmagnetic. In Fig. 9, mineralogical phases of the Magnetic I fraction are presented in comparison with BR and the tube furnace sinter.

Although Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 are the main mineralogical phases of iron, in the highest magnetic sample (Magnetic I), perovskite, ilmenite, and gehlenite also exist. Moreover, scanning electron microscope (SEM) analyses combined with EDS (Fig. 10), have demonstrated the existence of Si phases together with the iron ones. Analyzing the distribution of the elements, the white particles are composed principally of Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3, but some SiO2 is also detected as inclusions in the scratches (black area on white particles) of the surface (Spectrum 2, Fig. 9). As Chao Li et al. have shown in their work [18], when iron, silicon, and calcium are finely distributed in a matrix, they are commonly complexed together. This makes their fractionation through magnetic separation a very hard issue. On the other hand, Spectrum 3 (Fig. 10) confirms the existence of a complex matrix that entraps the iron magnetic phases.

An alternative route was then explored by performing tests at higher temperature (1100 °C) and with C/BR = 0.225, favoring metallic iron formation. The purpose of this work was the intensification of reduction conditions to produce metallic iron nuggets which could be more easily and efficiently liberated from the complex matrix by means of the magnetic separator. XRD patterns of these experiments are shown in Fig. 11.

Hematite and goethite were completely transformed into metallic iron after being roasted at 1100 °C for 4 h, while the other elements (Ca, Si, Al, Ti, and Na) are present mainly in sodium and calcium aluminosilicate phases as well as perovskite. In addition, Al is also present in the sinter as corundum.

SEM–EDS analyses have shown the presence of melted metallic iron (Spectrum 7, Fig. 12) concentrated in some grains of the material, entangled in a matrix mainly composed of calcium, aluminum, and silicon (Spectrum 3, Fig. 12).

After the reductive roasting process, the samples were ground (particle size < 90 μm) to increase the liberation of the metallic iron phase from the matrix and, following the procedure already explained above, three magnetic fractions were produced by means of WHIMS. The chemical analysis of sinter and the three fractions is shown in Fig. 13.

As is seen in Fig. 13, metallic iron is concentrated in the MAG I fraction and is diluted significantly in NM residue although the iron content is still high. Fe occurs in NM fraction as very small, almost spherical metallic particles (< 5 μm) entrapped inside a solid matrix that contains nearly all sinter constituents (Fig. 13). This is attributed to the fact that BR contains significant amount of ceramic-forming constituents (such as SiO2 and Al2O3) as well as fluxing oxides (such as Na2O and CaO), which during the reductive roasting process at 1100 °C form a ceramic precursor that sinters the residue. Although the roasted residue (sinter) was ground to liberate the magnetic iron particles, this proved to be an inefficient procedure for the effective magnetic separation of iron as the MAG I fraction (even though concentrated in metallic iron) contains considerable amounts of impurities (Fig. 14). By increasing the intensity of the magnetic field, a new fraction MAG II was separated, which however looks like the initial sinter as seen in Fig. 12. Moreover, the produced NM fraction amounts to only the 15% of the initial sinter material, which contains almost 71% noniron-bearing phases (Fig. 13) indicating once more, the inefficient separation of metallic iron due to its entrapment inside the ceramic matrix.

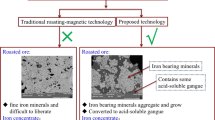

A possible scenario to increase the recovery of iron from BR is to divide the process in two steps. First, to apply soda roasting processing of BR by adding sodium carbonate as flux to transform all the alumina-bearing phases of BR to soluble sodium aluminates followed by alkali leaching to recover alumina [19]. During this step, the ceramic-forming components as well as the fluxing oxides are effectively removed from the residue, while, at the same time, the alumina is recovered from the BR.

Second, the soda roasting residue, mixed with a carbon source, could be roasted to selectively transform the nonmagnetic iron phases into magnetic ones avoiding in this case the ceramization of the matrix due to the lack of appreciable amount of ceramic-forming constituents and thus improving substantially the efficiency of the performed magnetic separation process.

Conclusions

This work has demonstrated that iron oxides contained in bauxite residue have been transformed into magnetite and maghemite after roasting process in the presence of metallurgical coke as carbon source (C/BR ratio = 0.180) at 800 °C. The result was the production of sinter with high-intensity magnetic properties. Following wet magnetic separation, SEM and XRD analyses of the magnetic fraction revealed the existence of calcium aluminum silica oxides on the surface of iron grains that reduced Fe enrichment in the magnetic concentrate.

Successively, other experiments were performed with high temperature (1100 °C) and C/BR ratio (0.225) to intensify reducing conditions and produce metallic iron. Results of magnetic separation again have shown the same problems with calcium aluminum silica phases attached to metallic iron. The presence of nonmagnetic BR oxides reduced the purity of the magnetic fraction.

The results of this work showed that the ceramic-forming constituents (especially Al2O3) have to be removed from the BR before its reductive roasting so that the separation of magnetic iron phases from the nonmagnetic matrix can be performed efficiently.

References

Pontikes Y (2005) Red mud: production. http://redmud.org (2005). Accessed 13 May 2018

Balomenos E, Panias D, Paspaliaris I (2011) Energy and exergy analysis of the primary aluminium production processes—a review on current and future sustainability. Miner Process Extr Metall Rev 32:1–21

Evans K (2016) The history, challenges, and new developments in the management and use of bauxite residue. J Sustain Metall 2(4):316–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0060-x

Li LY (2001) A study of iron mineral transformation to reduce red mud tailings. Waste Manag 21:525–534

Bánvölgyi G, Huan TM (2010) De-watering, disposal and utilization of red mud: state of the art and emerging technologies. TRAVAUX 35:431–443

Balomenos E, Davris P, Pontikes Y, Panias D (2017) Mud2Metal: lessons learned on the path for complete utilization of bauxite residue through industrial symbiosis. J Sustain Metall 3(3):551–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0110-4

Kumar RS, Premchand JP (1998) Utilization of iron values of red mud for metallurgical applications. Environ Waste Manag. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2077.7446

Bonomi C, Cardenia C, Tam P, Panias D (2016) Review of technologies in the recovery of iron, aluminium, titanium and rare earth elements from bauxite residue (red mud). In: Proceedings of 3rd International Symposium on Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM III), Lisbon, Portugal

Borra CR, Blanpain B, Pontikes Y, Binnemans K, Van Gerven T (2016) Recovery of rare earths and other valuable metals from bauxite residue (red mud): a review. J Sustain Metall 2:365–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-016-0068-2

Liu Z, Li H (2015) Metallurgical process for valuable elements recovery from red mud—a review. Hydrometallurgy 155:29–43

Xenidis A, Zografidis C, Kotsis I, Boufounos D (2009) Reductive roasting and magnetic separation of Greek bauxite residue for its utilization in iron ore industry. In: Light metals 2009, The Minerals Metals & Materials Society, San Francisco, pp 63–67

Balomenos E, Kemper C, Diamantopoulos P, Panias D, Paspaliaris I, Friedrich B (2013) Novel technologies for enhanced energy and exergy efficiencies in primary aluminium production industry. In: Proceedings of the First Metallurgical & Materials Engineering Congress of South-East Europe, pp 85–91

Borra CR, Blanpain B, Pontikes Y, Binnemans K, Van Gerven T (2016) Smelting of bauxite residue (red mud) in view of iron and selective rare earths recovery. J Sustain Metall 2:28–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-015-0026-4

Liu Y, Naidu R (2014) Hidden values in bauxite residue (red mud): recovery of metals. Waste Manag 34:2662–2673

Binnemans K, Jones PT, Blanpain B, Van Gerven T, Pontikes Y (2015) Towards zero-waste valorisation of rare-earth-containing industrial process residues: a critical review. J Clean Prod 99:17–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.089

Sajó IE (2005) XDB powder diffraction phase analytical system, Version 3.0, User’s Guide, Budapest

Földvári M (2011) Handbook of thermogravimetric system of minerals and its use in geological practice. Occasional Papers of the Geological Institute of Hungary, vol 213

Li C, Suna H, Baic J, Lia L (2010) Innovative methodology for comprehensive utilization of iron ore tailings. Part 1: the recovery of iron from iron ore tailings using magnetic separation after magnetizing roasting. J Hazard Mater 174:71–77

Zhu D-Q, Chun TJ, Pan J, He Z (2012) Recovery of iron from high-iron red mud by reduction roasting with adding sodium salt. J Iron Steel Res Int 19:1–5

Acknowledgements

The research leading to the results in this study has received funding from the European Community’s Horizon 2020 Program ([H2020/2014–2019]) under Grant Agreement No. 636876 (MSCA-ETN REDMUD). This publication reflects only the authors views, exempting the Community from any liability. Project website: http://www.etn.redmud.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The contributing editor for this article was I. Sohn.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cardenia, C., Balomenos, E. & Panias, D. Iron Recovery from Bauxite Residue Through Reductive Roasting and Wet Magnetic Separation. J. Sustain. Metall. 5, 9–19 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-018-0181-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40831-018-0181-5