Abstract

The aim of the paper is to analyse the main internal drivers of the increase and adoption of online activities carried out by firms in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic. While the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on several measures of firm-level performance has been debated in many papers, not enough effort has been devoted to investigating its digitalization impact, especially with respect to the drivers of firms operating in transition countries. To this end, we explore a very detailed firm-level dataset, drawn from the World Bank Enterprise Survey (WBES) combined with the Covid-19-ES Follow-up Survey, for 22 Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries. Our findings reveal that (i) higher online activity is associated with higher digital and technological endowment of the firm and (ii) this relationship is shaped by external factors, such as country-level digital infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The development of technologies, especially those related to Industry 4.0 (such as, big data, cloud, internet of things), spurred governments to further invest in the digital transformation of the economy, in terms of both firms’ digital capabilities and countries’ digital infrastructures. The ICT adoption process is indeed a factor potentially influencing a country’s path of economic growth through different channels, such as the improvement of business competitiveness (Pradhan et al., 2018), the dissemination of technological knowledge, learning and innovation (Vu, 2011; Vu et al., 2020).Footnote 1

Recently, the digitalization phenomenon, involving a progressive change through which firms create their strategic and competitive advantage, has increasingly received much attention from business literature. However, as pointed out by Verhoef et al. (2021), despite the widespread phenomenon of progressive wider involvement of firms in digital technologies’ adoption, most of the literature just focused on its potential outcomes with different perspectives (Ardito et al., 2021; Gaglio et al., 2022; Gal et al., 2019; Marszałek & Ratajczak-Mrozek, 2022), not paying enough attention to the way the process of digitalization is unfolding. Similarly, the digitalization process has received scant attention with respect to its determinants (Li & Shao, 2023; Zhu et al., 2024). Instead, the complex design of firm digitalization has several features that need to be further examined (Björkdahl, 2020), since it also requires a suitable digitalization culture (Martínez-Caro et al., 2020) and an organizational flexibility (Reuschl et al., 2022).

In this regard, the COVID-19 pandemic represented a natural experiment useful to observe the consequences of external shocks forcing firms to invest more resources in digitalization, thus offering an opportunity to understand firms’ behaviour in times of crisis. Some of the few directions along which the business literature developed around the Covid-19 impact mainly pertain to the financial constraints (Khan, 2022), innovation (Jin et al., 2022), productivity (Muzi et al., 2023), internationalization (Jordaan, 2023), and investment expectations (Coad et al., 2023). The role of technology, in the form of increasing digitalization, in affecting firms’ ability to survive has also been analysed in the Covid-19 context (Comin et al., 2022; Copestake et al., 2024; Takeda et al., 2022).

However, what is lacking, both within the mentioned literature and in the more general literature about digitalization, is the focus on internal drivers that may affect the increase in firm-level digital activities. An exception is provided by Avalos et al. (2023) who find that, especially in developing countries, most of the firms that after the pandemic increased their investment in digital solutions were already characterized by some kind of digital readiness in the pre-pandemic period. However, Avalos et al. (2023) do not analyze neither the differential impact that the technological readiness of firms, that is their internal technological endowment, may exert on the adoption of digital solutions nor whether the impact of firm-specific characteristics might interact with the external factors, measured by the public support given in this crisis period as well as by the country’s digital endowment.

In this framework, our contribution to the literature is firstly to offer a comprehensive picture of the internal drivers, posing particular attention to the technological endowment, that might have influenced the decision of firms to start or increase online activity in response to the pandemic crisis. Further we see whether the effect of these factors might be shaped by the country’s technological structure. The main source of data is the World Bank Enterprise Survey (WBES), useful to retrieve the pre-pandemic characteristics of firms, combined with the Covid-19-ES Follow up Survey, conducted in several rounds and useful to obtain the digital business response to the Covid-19. In particular, the follow-up reinterviewed a sample of firms for which data from the WBES are available, allowing us to carry out comparable research across countries and to control for firm pre-pandemic characteristics. The analysis focuses on a sample of more than 9,500 firms operating in a group of 22 Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries.

The second contribution of our paper comes from the fact that this dataset offers generalizable results on a homogenous group of countries. Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries have not received much attention in the literature related to the Covid-19 effects, with just few exceptions (Janzen & Radulescu, 2022). The importance of aggregate and individual-level factors that may impact on the decision of a firm to enhance its level of digital activities may be quite different in said countries, characterized by specific institutional features potentially affecting the way firms produced new technological knowledge (Krammer, 2019). In those countries, the innovation path has been guided by a combination of national knowledge base and R&D investments, coming from private sources as well as from global sources (Krammer, 2009). The peculiarities of a firm’s innovation activities in those countries have been thoroughly investigated (e.g. Rodriguez et al., 2022), but, again, the path of digital adoption in response to the pandemic has not received attention.

Identifying such patterns in transition countries have policy implications since it could help to figure out whether there can be some bottlenecks and institutional hurdles that need to be removed in order to increase the rate of digitalization. Starting from 2014, the European Commission has measured Member States’ digital progress using the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), showing that in 2022 some EU countries, such as Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, are the EU frontrunners in the adoption of digital technologies while other transition countries lags.Footnote 2 One of the motivations is that, as we know from economics of innovation literature, transition countries still suffer from institutional weakness and a different external context may impact on the way firms accomplish innovation results (Crowley & McCann, 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2022).

If we enlarge the perspective to developing countries, the adoption rates ofr advanced technologies, such as secure servers, enterprise networks, inventory management, and e-commerce are even lower than in developed countries, despite extensive internet access. This is largely because these technologies have not penetrated deeply into these nations (World Bank, 2016). Similarly, UNCTAD (2021) highlights the persistent digital gap between developed and developing countries, particularly in terms of internet connectivity and usage. Bridging this gap remains a major challenge for development efforts, considering that the pandemic has further emphasized and worsened these disparities.

Our results quite clearly point to the role of the internal technological structure of a firm to explain the extensive margin of online activity adoption, with specific reference to the role of owning a website, which is a proxy of digital capabilities already in place before the pandemic, and previous investment in R&D, which accounts for the existing knowledge scanning capability as well as recombination into new pieces of knowledge. With respect to the external factors, we find that if firms are part of a high developed digital infrastructure context, the role of internal R&D endowment is not as crucial as for firms operating in a less developed one. This quite interesting result leads us to conclude that internal and external factors may be considered as substitutes rather than complements in affecting online activities, pointing to a peculiar dynamic innovation path. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical framework, Section 3 illustrates data used, Section 4 describes the empirical setting and the model estimated, and Section 5 discusses the results. Section 6 concludes.

2 Theoretical framework

The digital transformation of the economy, characterized by the adoption of new digital technologies, the creation of digital platforms, and the development of suitable digital infrastructure, is not a recent phenomenon; it began several decades ago, with the onset of the ICT revolution.

The digitalization process is manifold and it can be studied from different perspectives and through multidisciplinary lenses (Verhoef et al., 2021): it may have disruptive implications for firms, leading to a process of reorganization required to derive benefits from the adoption of such technologies (Nambisan et al., 2019). It is still a matter of debate whether firms may all gain in terms of higher performance, due to the digitalization process, or it may also bring some adverse effects, or even risks (e.g. Chouaibi et al., 2022; Kohtamäki et al., 2020), considering that most of them are mediated by dynamics on the labour markets (Balsmeier & Woerter, 2019). As evidenced in the introduction, even though the digital paradox may be at work, employing ICT specialists and adopting digital solutions may also help to improve firm’s labour and total productivity (Cette et al., 2022; Rahayu & Day, 2017).

However, although there is a growing body of literature on the impacts of digitalization, starting with the seminal contribution by Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2003), the same cannot be said for the determinants of firm digital adoption. In particular, Verhoef et al. (2021) pointed out how the process of digital transformation, which implies not only the availability of digital resources, but also the need to adopt a different organizational structure of a firm, may spur the development of new business models. As evidenced in the literature review by Jung and Gómez-Bengoechea (2022), the factors affecting digital adoption can be classified into both business and aggregate level factors. In this respect, they borrow from Consoli (2012) and Skoko et al. (2007) who focus mainly on five factors: personal, organizational, environmental, technological, and economic. Although their framework was based on the role of ICT adoption in the early phase of digitalization, we think it can still be relevant for the present wave, characterized by the adoption of more sophisticated devices of digitalization. It should be underlined that as the digitalization process encompasses several different technologies, spanning from simple internet usage to the adoption of digital solutions for sales (i.e. e-commerce), the literature nevertheless lacks an encompassing framework to analyse them all together. However, most of the papers focusing on the drivers of e-commerce, especially with respect to SMEs in developing countries, refer to similar sets of determinants, namely organizational, technological, and environmental factors (e.g. Awiagah et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2013; Jeon et al., 2006).

This is why in our framework we focus on internal firm-level and external country-level drivers. Firms can be characterized by different degrees of readiness to digital technologies’ adoption, but, at the same time, the country’s infrastructure endowment and the government policy should provide firms with the support to start or fruitfully continue their process of digitalization. In this respect, borrowing from a more general literature dealing with determinants of innovation adoption, we can draw some hypotheses more related to digital adoption drivers.

In this framework, individual factors related to specific top management skills or attitudes, personality traits or to specific technological skills of the workforce are crucial drivers. Recently, Li and Shao (2023) specifically test the importance of top management in guiding the reconfiguration of the firm’s strategic orientation goals. Similarly, organizational drivers are relevant in the process of digital transformation. Coherently with the idea that the digitalization is unfolding through an encompassing process, some papers take into consideration not only the technological capabilities, but also the strategic orientations of the firm and, in particular, its own strategy (Kane et al., 2015). The focus on dynamic capabilities, rooted into the approach of a knowledge-based view of the firm, attaches quite a great value on the role that employee’s skills and characteristics may play in this respect. Along the same way, technological and organizational factors together are the most powerful internal drivers of digitalization. The concept of organizational readiness is relevant in our case and, as evidenced by Hameed et al. (2012), it needs to be addressed together with other moderator factors related to the technological, environmental, and individual drivers.

However, our research question is motivated not just by the need to dig deeper into the determinants of digitalization, but also by the opportunity to understand how they are affected by the historical event of the pandemic.

In this respect, the Covid-19 pandemic has rapidly advanced the adoption of modern technologies and transformed work patterns and business strategies, acting as a catalyst for the increased use of digitalization in work organization, leading to both positive and negative outcomes (Reuschl et al., 2022; Vargo et al., 2021). While it is recognized that the pandemic can be seen as a “great accelerator” of the digitalization process, not enough effort has been devoted to understanding what the drivers of such a process can be (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021). Nevertheless, even before this disruptive event occurred, digital adoption represented a trend which was, and still is, growing at a fast pace being quite heterogenous across firm-sector and country characteristics (Gal et al., 2019).

A general theoretical overview that explores the influence of Covid-19 on the digitalization of businesses at a global level, examining various factors driving and hindering the digitalization process in response to the pandemic, is provided by Amankwah-Amoah et al. (2021). Their framework can result relevant in our perspective as they point out some barriers to digitalization. They highlight that especially the lack of technological infrastructure may cause a process of digital divide; moreover, institutional constraints, such as the lack of specific national laws, the level of government support, and the lack of government investment may hinder the building of a suitable infrastructure. Finally, they also evidence a kind of organizational constraint. In this framework, it appears that two sides of the issue, already evidenced before in the discussion about the digital determinants in general, need to be taken into consideration: one that is more internal to the firm and the other that is more related to the external context in which a firm operates.

Thus, focusing on the Covid-19 literature, we recognize that the impact of the pandemic is mainly analyzed to understand whether the presence of some kind of digital readiness has favoured firms in their survival path.Footnote 3 A positive impact has been found by Muzi et al. (2023) and corroborated by other cross-country analysis such as Santos et al. (2023), or by single country studies in which other firm-level factors, such as size, age, and the adoption of digital technologies are analysed (e.g. Bloom et al., 2021; Trinugroho et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). In the same way, the emphasis on the importance of technological sophistication on firm resilience is evidenced by Comin et al. (2022) for three emerging countries, namely Brazil, Senegal and Vietnam. Being already endowed with a significant technological infrastructure, such as the one relative to a website, is a relevant driver for a firm to adopt suitable technologies to continue its presence on markets. From a descriptive point of view, Ali and Ebaidalla (2022) reveal that firm size and foreign ownership foster digital transformation, highlighting a strong correlation between the Covid-19 outbreak and digitalization and suggesting that service firms are more likely to embrace digital technologies.

However, in all these papers, the likely impact that the Covid-19 pandemic may have had on digital activities is not taken into consideration as we do. An exception is Avalos et al. (2023) who consider the motivations that may induce firms to digitalize after the pandemic. They include several internal drivers, such as R&D and the use of websites, the financial support received by firms, but without considering how they can interplay with external context drivers.Footnote 4 Borrowing from this framework, we derive the following hypothesis to test:

-

HP 1. Technological and organizational firm-level factors positively impact on digital adoption in response to Covid-19

The importance of a country’s ICT infrastructure is to build national technological capabilities. Pradhan et al. (2018) evidence that investing in the improvement of IT infrastructure, especially broadband and internet deployment, is among the most relevant drivers of an increasing GDP per capita. Many other studies for both high-income and low-income countries reveal that ICT infrastructure may have both direct and indirect effects and some papers evidence how countries do not gain to the same extent from that kind of investment (e.g. Myovella et al., 2020; Niebel, 2018; Appiah-Otoo & Song, 2021).Footnote 5

In addition, as evidenced in the general literature about digitalization, factors that are external to the firm and to the environmental context are equally important. In this respect, the only work that examines whether it can be true in the pandemic period is the one by Doerr et al. (2021), who analyse the role played by the technological capacity of countries in affecting firm recovery. Using data from the World Digital Competitiveness Ranking they find that being endowed with better digital infrastructure (an improvement by one standard deviation) can enhance by 4% the revenues of the average firm.

While the combined impact of external and internal drivers has not been investigated in the digitalization literature, drawing from the importance given to the external actors of the innovation context within the innovation system literature, we posit that internal drivers, especially those related to technological endowment, can be supported by a well-established technological infrastructure, positively reinforcing their effect on digitalization.

We draw the following hypothesis to test:

-

HP 2. The technological country-level digital infrastructure shapes the relevance of internal factors for digital adoption in response to COVID-19

3 Data and descriptive statistics

The dataset employed for our empirical analysis has been collected by the WBES and then combined with the Covid-19-ES Follow up Survey (COV-ES), both released by the World Bank. The firms included in the Enterprise Survey, once surveyed in 2019, were interviewed again in up to three rounds of follow-up after the Covid-19 outbreak. The three rounds cover the period spanning from May 2020 to October 2021.Footnote 6 Each firm with at least 5 employees and conducting its activities in the manufacturing or other sectors (retail and wholesale trade, construction, and services) is included in the sample. Several variables are available, especially those showing information on the business environment where the firm operates and specific within-firm characteristics (age, size, internationalization, financial sources, and technological capital). Even though the WBES database was collected for more than 30 countries (both developed and developing), we focused on a group of 22 Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries, considering a final sample of 9,570 firms, as one of the aims of our paper is that of analysing a homogenous group of countries, to understand whether common drivers at firm-level can be detected. To select 22 countries included in the sample we follow three criteria: (i) we select all countries from the WBES database for which full-data on 2019 are available; (ii) we select only those countries for which a follow-up, in at least one round over the Covid period, is available; and (iii) we retain only countries for which all variables included in the analysis are available.

3.1 Dependent variable

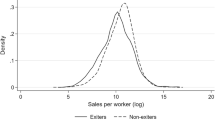

The COV-ES firms were asked whether they initiated or enhanced online business activity in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic. We therefore built a dummy variable which is equal to one if the firm answered “yes” to the previous question. In building this variable, we considered all the rounds of the COV-ES follow-up (from the first quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2021). Table 7 in the Appendix provides an overview of the distribution of sample firms on countries and time (year-quarter). From the descriptive statistics reported in Table 1 we can see that nearly 20% of the firms initiated or enhanced online business activity in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic.Footnote 7Additionally, we document that firms operating in other sectors, including service, are more likely to introduce online activities than manufacturing firms (21.2% and 17.2%, respectively), as well as firms operating in Azerbaijan and the Russian Federation (57% and 54%, respectively).Footnote 8

3.2 Internal drivers

As hypothesized, to study the drivers of the probability of adopting or enhancing online activities, we firstly account for some internal firm-level characteristics that were measured before the pandemic outbreak, that is in 2019.Footnote 9 All pre-pandemic characteristics are drawn from the WBES. In particular, we focus our attention on the role of technological structure, partially borrowing from Avalos et al. (2023), structural firm characteristics, the degree of internationalization, and access to financial resources.

Our key explanatory drivers refer to technological endowment, accounting for the digital readiness of the firm. In the benchmark estimates we use two variables: the presence of a website before the pandemic, that is a dummy equal one if the establishment has its own website, and the R&D investment, which is measured as a dummy variable equal one if the establishment invested in in-house or external R&D, over the last three years.Footnote 10 As evidenced in the conceptual framework, we expect these variables to be significantly and positively correlated with the adoption or increase of online activities. In other terms, firms already technologically equipped, are more likely to start new business online activities (Wagner, 2021). Descriptive statistics (Table 1) show that on average 69% of firms owned their website and 22% of them invested in R&D before the pandemic period.

Structural characteristics are captured by usual firm-level controls, such as age since firm inception and size, measured as the number of permanent full-time employees at the end of 2019. The latter variable is expected to positively affect digitalization, as larger firms may be endowed with more resources to be invested in online activities. Small firms might both be affected by higher exit rates (e.g. Muzi et al., 2023) and be endowed with higher flexibility to adapt to a new organizational configuration that online activities may require. Firms in our sample are endowed with 74 employees on average and are on average 21 years from their inception. Firms also need financial resources not only as a way of facing sudden external shocks, but also as a way of investing further resources in new digital tools (Alraja et al., 2023). For this reason, we include a variable representing the access to financial resources provided by intermediaries, measured as a categorical variable ranging from zero (i.e. no obstacle to access finance) to four (i.e. a very severe obstacle).

Furthermore, the role of policies needs to be taken into consideration: given the existence of state support to help businesses cope with the negative consequences of the pandemic, some papers attempt to understand the role of funding policies to recover from the decrease in sales. Cirera et al. (2021) evidence the issue of mismatch and mistarget of support policies, that were particularly limited in developing countries and for more vulnerable as well as small firms. Besides Ali and Ebaidalla (2022), who find that firms receiving government support are more likely to adopt digital solutions, Janzen and Radulescu (2022) analyse the role of government support in Eastern European Countries pointing to a distinction between small and large firms, evidencing a mild effect for the latter but a much higher relevance for the former.Footnote 11 Less evidence has been devoted to understand whether this kind of support may foster also a digitalization process: thus, we account for this determinant which depends on the institutional context in which it is embedded. The variable refers to the public support received by national or local government, in facing the crisis, since the Covid-19 outbreak.Footnote 12 On average, the probability of receiving an external government support is 37% in the observed sample.

Variables related to the presence of the firm on international markets include direct exports (i.e. not intermediated foreign sales) as a share of total sales and the share of firm owned by private foreign individuals, companies or organizations. If firms are part of an international network, either through export or direct investment, they can be exposed to the shocks affecting the global value chain to a greater extent. At the same time, being internationally connected within a global network may favour the ability to have access to more resources to sustain productivity and growth. Even though the literature mainly examines whether digitalization may shape the presence on international markets (e.g. Añón Higón & Bonvin, 2023), it is also true that being present in global markets may be a further motivation for which after a period of crisis involving interruption of international linkages, it is crucial to use online activities as a way to stay connected with foreign markets. This would suggest positive coefficients for those variables. The share of direct exports in our sample is on average 13% and the share of foreign ownership is about 8%.

As we put particular emphasis on technological variables as proxy for firm technological readiness, in Section 5 we conduct additional regressions adding one at a time variables depicting the organizational and technological capital firms are endowed with, useful in carrying out digital activities. They are first captured by the distinction between production and non-production workers. The number of non-production workers is used as a proxy for skilled workers, which is expected to be positively linked to the probability of increasing online activities. Secondly, we consider a dummy equal to one if the firm used external knowledge in the last three years.Footnote 13 The ability of the firm to gather knowledge from several external sources can be adopted as a proxy for the capability to scan and search for knowledge outside the firm, beyond R&D. As we are aware not all non-production workers are part of the skilled workers category, we also use a variable which should account for their higher education, that is the share of permanent full-time employees with a university degree.

Pairwise correlations between variables are reported in Table 2.

3.3 Context drivers

As evidenced in the conceptual framework, we cannot account for the Covid-19 impact on firm digitalization solely through firm-level drivers, as it is also largely explained by the context in which the firm operates.

Therefore, we also need to account for the interplay between country-level technological endowment and firm-level digitalization drivers. As Amankwah-Amoah et al. (2021) point out, technological infrastructure is one of the most crucial barriers to start or increase a process of firm-level digitalization: it is particularly useful in reducing the digital gap between urban and rural areas and between developed and developing nations. To account for a country’s technological infrastructure, we use the fixed broadband subscriptions (per 100 people) and the number of secure internet servers (per one million people). We also use the digital adoption index for the year 2016 (the most recent available), composed of three sub-indexes that measure countries’ digital adoption across three dimensions of the economy: people, government, and business.Footnote 14 The index, spanning from zero to one, measures the “supply-side” of digital adoption. We adopt such indicators to shape the impact of our internal drivers depending on the fact that a firm operates in a country ranked above or below the sample average in each variable.

4 Empirical methodology

Since the dependent variable takes values zero or one, we estimate the benchmark regressions using a probit model. The baseline regression is the following:

The subscript i indicates the firm, while j the sector where the firm operates (2-digit Isic rev. 3.1), k the country to which the firm belongs and t denotes the quarter-year of the interview over the follow-up period. The dependent variable reflects how the pandemic affected firms’ business online activities, as described in Section 3.1.Footnote 15 The set of key explanatory variables named technology includes a dummy indicating whether the firm owned a website and a dummy for R&D, both in 2019. The vector of firm-level controls, firmc, includes variables to account for structural characteristics, the presence in international markets and the possibility to access external financial resources. We consider both sets of variables referred to the pre-Covid-19 period and assess their relationship with the way the firms reacted to the outbreak in terms of digitalization. In other words, we aim at investigating how the response to the pandemic, in terms of digital adoption, depends on firms’ characteristics observed before the outbreak.

The strategy of adopting lagged firms’ characteristics allows us to address potential endogeneity between internal drivers and the adoption of online activities in response to the pandemic, as also pointed out by Muzi et al. (2023). Each regression includes country, sector, and quarter-year fixed effects to control for time invariant factors that we cannot measure and that can be correlated with the dependent variable. As usual, an error term is included. All regressions include robust standard errors, clustered at the sector-level.

However, we are aware that our regressions may still be affected by potentially endogeneity, especially due to reverse causality. A variable that can be affected by this issue is the presence of a website before Covid-19. A further motivation for endogeneity to occur is due to omitted variables not included in our framework, but potentially affecting both the explanatory dummy of owning a website and the probability of adopting online business activity in response to the pandemic. For both reasons, we also tackle the problem of endogeneity using a recursive bivariate probit and appropriate instruments for it, that we detail in sub-Section 5.3.

5 Results

5.1 Internal drivers and firm heterogeneity

Table 3 shows our benchmark estimates obtained estimating Eq. (1) both on the whole sample (column (1)) and considering different sub-samples of firms depending on their size, the sector of activity, its digitalization level and the group of countries to which it belongs. In accordance with HP 1, in all regressions the variables depicting the technological structure of the firm provide a clear result: they are positively correlated with the probability of carrying out online activities in response to the pandemic. In particular, both website adoption and R&D are significant at the 1% level. The first variable shows the highest average marginal effect (0.077), meaning that firms that had an online presence before the pandemic, with their own website, started to be nearly 8% more likely to improve their online activities in response to Covid-19. The investment in R&D generates a 3.8% higher probability that the firm may increase online activities.

With respect to other firm-level controls, we first recognize that size and age are respectively positively (1.4%) and negatively (-1.6%) correlated with the probability of observing a change in online activities, in line with our expectations. Interestingly, the marginal effects of the variables accounting for the presence of the firms in international markets are negative and significant (-2.1% and -0.1%, respectively). In other words, if a firm is foreign owned or displays higher direct export share it will adopt or increase online activities with lower probability. This seems surprising and unexpected at first, but we can infer that those firms that are already part of international networks are less eager to search for new customers and markets as it would happen for domestic firms, that need new strategies to survive and to generate value added activities. A connected and further motivation for this negative coefficient is that after the Covid-19 pandemic a process of back-shoring of production is starting to materialize: it means that the delocalization of production that happened quite intensively in the ‘90s and was prolonged over the years, recovering after the financial crisis in the 2008–09, is inverting its trend after Covid. The adoption of industry 4.0, including digital technologies, may also be a driver of the said trend (e.g. Dachs et al., 2019) but also the reverse relationship may be at work and, in any case, the relationship is not so robust (e.g. Kamp & Gibaja, 2021) leaving room for different final results. In the end, the result may also stand for the fact that internationalized firms are also more familiar with these kinds of new technologies because their production processes already implied high degree usage of digital tools, meaning that the need to increase them is not that pressing.

Contrary to our expectations, the impact of the ability to access external finance is not significant (the marginal effect is 0.3%), even though the coefficient may capture the effect of other variables, in particular it may account for a size-related effect. Instead, the support received in times of pandemic by the local and national government proves to be important, providing a positive stimulus to digital adoption by increasing it by more than 5%.

In the same Table 3 we split the sample according to the size of the firm (columns (2) and (3)).Footnote 16 We note in column (2), depicting the results for small firms, a significant and positive marginal effect for access to finance (0.7%), confirming that for those firms the role of credit is more relevant than for larger firms. The role of technological variables is equally important between the two sub-samples, even though the magnitude of the coefficient is higher for large firms, who draw on these resources to a greater extent. This result further confirms HP 1, considering the exception for variables related to internationalization.

We further disentangle the baseline estimates according to the share of jobs that can be done at home for each sector of economic activity. We borrow from Dingel and Neiman (2020) an index measuring the share of jobs performed at home, obtained aggregating the occupational classification to the 2-digit NAICS industry-level. Their index reveals that managers, educators, and those working in computers, finance, and law are largely able to work from home. Instead, other types of occupations like farming, construction, and production workers are not suitable to do that. The index is constructed from several standardized and occupation-specific descriptors, weighting the share of jobs done at home by the salary, since workers in occupations that can be performed at home are more likely to earn more.Footnote 17 In this way we can see whether a firm operating in a sector of economic activity characterized by a higher share of jobs that can be done from home shows a higher probability of increasing its online activities, exploiting the labour and organizational structure of the firm depending on the level of digitalization of the sector. Again, confirming HP 1, we see from columns (4) and (5) that our technological variables are equally important for both samples but the marginal effect is lower for firms with a high intensity of jobs that can be done at home. This is probably due to the fact that those firms already had a quite relevant organizational capacity, allowing them not to rely to a greater extent on their technological capabilities.

Finally, the sector to which the firm belongs can be relevant for the final effect on digitalization. We thus distinguish between manufacturing and firms that are part of other sectors (i.e. retail and wholesale trade, construction and services). In line with HP 1, we find that technological variables are important determinants of online activities, even though the magnitude of all coefficients is higher for the group of other sectors, including services. This is a proof of the fact that the service sectors rely more on intangible kinds of activities than manufacturing firms do. Finally, even though countries that are part of the sample are quite homogeneous, we also run regressions in column (8) just considering Eastern European countries (thus excluding Central and Eastern Asian Countries): the results confirm what was found previously in accordance with HP 1.

As our core variables mainly show quite robust behaviour across all estimates, we further analyze the role of internal organizational and technological capital by adding other variables that can account for that. Table 4 shows the results. In each column we have added (or replaced) one variable at a time. In the first place, columns (1) and (2) distinguish between production and non-production workers as drivers of digitalization: we see that it is only the latter that, being endowed with higher technological skills, can impact positively on digital activity (1.1%). Moreover, we note that in this last case, the role of R&D is not anymore significant. This stands for the fact that some degree of substitution between these variables can be present.

In column (3) we also document that external knowledge can be relevant and highly significant in improving the probability of online activities, while in column (4) we also account for the skills of the employees, introducing the share of those with a university degree. Even though the results point to a coefficient positively correlated with online activities, the size of the marginal effect is quite small (0.1%).Footnote 18 These results confirm our expectations related to HP 1, as the role of technological variables point to be an important one when measured through different proxies.

5.2 Context drivers

As evidenced in the conceptual background, not only the internal capabilities of the firm can be important in generating a higher level of online activities, but also the external context in which the firms operate has its relevance, since it provides the technological infrastructure from which the firms can benefit further spillover effects. In order to account for the role of technological infrastructure at the country-level, we have carried out several sample splits. Our motivation in doing this kind of exercise is that of considering whether external drivers can contribute to moderating the impact of internal drivers. Table 5 displays such results: we note that, contrary to what proposed in HP 2, there are not relevant differences between the impact of the website variable in the subsamples. It means that the external technological structure is equally relevant in fostering online activities through strengthening the internal factors. In all the subsamples of firms operating in less endowed countries (columns (2), (4) and (6)) the marginal effect of R&D is highly positively significant, while in high endowed countries it is not significant. This seems to point out that when external technological infrastructures are relevant and efficient, the role of internal R&D is less relevant in spurring digital adoption than where technological infrastructure are less efficient. This result can be also explained by the peculiar characteristics of the way innovation process has unfold in these countries: Krammer (2009), in his thorough study of transition countries’ national innovation system, points out that government’s contribution to R&D investment exceeds that of business R&D investment which is instead the opposite situation occurring in developed countries. For this reason, in these countries the two parts of the innovation system, the private and the public, still do not work together.

5.3 Robustness checks: endogeneity and further analysis

In this section, we address potential endogeneity of the technological structure of a firm. Since both the dependent variable and the fact of owning a website are binary, the model estimation requires using a recursive bivariate model (Wooldridge, 2010). In this model, that is made of two equations estimated simultaneously, the change of online activities is modelled as a function of the use of website, besides controlling for other firm-level drivers (Eq. 1). Meanwhile, the first stage is modelled as shown in the following equation, where the probability of having a website is expressed as a function of the same control variables as in Eq. (1), together with an appropriate set of four instruments.

The instruments that we propose for website refer to the idea that the poor quality of electricity supply influences business performances. Indeed, firms perform better if they operate in countries with better electricity connection (Geginat & Ramalho, 2018). Firms’ access to electricity has received much attention in developing countries, as they are typically threatened by energy poverty, i.e. the absence of sufficient choice in accessing energy services. Energy shortages, for instance, might negatively impact firm productivity, through higher prices of products and higher market prices of input (Bui & Nguyen, 2021; Xiao et al., 2022). Specifically, our selection of instruments borrows from the literature investigating the policies addressed to reduce the digital divide. Wang et al. (2022) provide evidence that the energy poverty negatively affects the households’ Internet use. Likewise, Armey and Hosman (2016), while investigating the factors influencing Internet adoption in developing nations, discover strong evidence indicating that expanding the accessibility of electricity in underserved segment of population significantly boosts the number of Internet users.

In particular, drawing from our dataset, we can build four instruments. The first instrument is a dummy equal to one if the establishment considers electricity a major or very severe obstacle to its current operations. The other instruments are three interaction terms between a dummy indicating the quantile of the distribution, in terms of size, to which the establishment belongs and a dummy equal to one if the establishment evaluates electricity as one of the five biggest obstacles faced in its current operations.

The two main requirements for the validity of our instrumental variables are satisfied, as evidenced by the tests reported in the bottom panel of Table 6. The Kleibergen-Paap F test (2.62 with a p-value of 0.053) indicates that our instruments are not weakly correlated with the endogenous regressors.Footnote 19 The overidentifying restriction has been tested through the Hansen statistic (1.862, and its p-value 0.601), which indicates that our instruments are also exogenous, i.e., uncorrelated with the error term and correctly excluded from the estimated equation. The coefficient of the website dummy in the main regression shows a positive effect on the probability of increasing digitalization: owning a website increases the probability of digitalization in response to the Covid-19 by 18.6% (column (1)). The instrumental variable approach is supported by the Hausman test, revealing that the endogenous regressors cannot actually be treated as exogenous.

In the same table, as a further analysis, we report the results of our benchmark estimate, considering different dependent variables to measure digitalization: the amount of online sales out of total sales (column (2)) and a dummy variable equal one when the firm started or increased remote work arrangements in response to the pandemic (column (3)). Regarding the intensive margin of online sales (column (2)), we see that the role of technological variables is still relevant, even though the size of the marginal effect is lower than that reported in column (1) of Table 1. The variables proxying for the international network have instead a positive impact, contrary to the negative one found for the extensive margin of digitalization, revealing that in order to serve the foreign markets, firms exploited the already existing online channels to a greater extent rather than opening new ones. Finally, a further relevant result is that access to finance plays a significant role in this case, indicating that, to expand the scale of the online activities, much more support is needed than just when deciding to do that.

The last column provides a quite interesting result with respect to the fact that firms with foreign ownership are those that increased the use of remote work more than other types of firms. This could be due to several reasons, but the most important is that many employees after the pandemic asked for a different work arrangement that those firms were able to provide also because of their larger experience in dealing with employees located in different parts of the world. In this respect, the impact of technological endowment continues to be very relevant as well as public government support, which proves to be highly significant; the latter result indicates that when firms were supported by the government, they were also able to avoid exiting the market and rearranged their work from home.

6 Conclusions

The path of digitalization of an economy has received quite relevant attention in recent years. While the importance of digitalization has been largely acknowledged in terms of the impact on the organizational structure of the firm as well as on its performance (Li et al., 2022), it is not clear which are the main drivers of firms’ digitalization, especially those that may have spurred the acceleration of adoption after the Covid-19 pandemic.

The economic disruption following the pandemic is a reality that the whole world experienced, even though some countries and firms were hit more than others. The supply shock impacted sectors differently as some of them – such as pharmaceutical – saw an unprecedent surge in demand, while others – such as transport – were hit heavily. Since then, many papers have started to question the impacts of such phenomenon at country and firm-level. Most of the analyses are related to the experience of developed countries, where the magnitude of the impact could be more easily detected. However, there are some papers highlighting that also in developing countries the effects have not been negligible (e.g. Avalos et al., 2023; Takeda et al., 2022).

In this respect, one of the geographical areas that have been under investigated, both with respect to the digitalization drivers and to the Covid-19 impact, is the one including Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries.

For this reason, in this paper, we have investigated a research question that, following the Covid-19 pandemic, has become much more relevant than before, due to the way the economic shock hit the firms asymmetrically, forcing them to find new ways to survive in the markets. Indeed, the Covid-19 pandemic has spurred a general acceleration of the digitalization of firms in order to cope with sudden closures (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021).

We focus our attention on the role that some firms’ and context features may have in enhancing online activities in response to the boost triggered by Covid-19. In this way, we have addressed a gap in the literature pertaining to the drivers of firms’ digitalization in transition countries. To do so, we used the World Bank Survey (WBES) combined with the follow-up survey available for 22 Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries. Our approach has been that of considering both internal drivers and external-moderators of digitalization, focusing in particular on the role of variables proxying for the technological endowment of the firms, such as the use of website and R&D extensive margin. Among the external factors we rely on suitable country-level digital infrastructure proxies to understand whether they may shape the way internal firm-level variables may impact on the probability of starting or enhancing online activities. We found confirmation of the high importance of variables related to the technological infrastructure of the firm, checking for other firm characteristics (size, age, international involvement, and access to external finance). In this regard, we observe an evident pattern of importance related to R&D internal variables when the technological infrastructure at the country-level is less efficient. This stands for the fact that the two technological efforts, internal and external, are substitutes rather than complements: it means that they do not foster synergies between each other. Our results are also robust to the inclusion of additional variables related to the technological endowment of the firms, such as the share of production and non-production workers and the share of employees with a university degree. A set of instrumental variable estimates corroborates our benchmark estimates.

All these results show a quite peculiar digitalization path that the group of Eastern European and Central-Eastern Asian countries are experiencing, pointing to the fact that the degree of importance of technological endowment both within and outside firms in further boosting the use of online activities is relevant.

Since business digitalization is a complex phenomenon, also contributing to the digital divide, our paper offers several recommendations to policy makers. In the first place, understanding the main factors that drive digitalization can give companies in transition nations a competitive advantage, as long as they are able to adopt specific strategies aimed at promoting digitalization efforts. Indeed, it indicates that policies should be addressed to support firms not only with financial resources to invest in digitalization, but also with technological skills and affordable access to energy infrastructures. However, this paper shows some limitations mainly attributable to data availability. Even though the WBES combined with the ES-follow-up allows us to investigate the role of pre-existing firm’s characteristics on digitalization choices in response to the pandemic, the data are cross-sectional. Consequently, the nature of our data prevents us to (i) control for firm’s unobservable heterogeneity and (ii) observe firms’ dynamics in a medium-large time period, even though some individual characteristics are measured as changes.

Data Availability

Data used to conduct the empirical analysis is publicly accessible at https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys.

Notes

However, at the macroeconomic level, it is debated whether some countries adopting ICT derive higher benefits than others in terms of growth (Appiah-Otoo and Song, 2021; Niebel, 2018). In this respect, the so-called “digital paradox” can explain this issue. As described by Solow (1987), who first introduced the concept calling it “productivity paradox”, technology development may not always go hand in hand with productivity growth. While discovered with reference to ICT adoption, it seems that it may also apply to the adoption of new digital technologies (Acemoglu et al., 2014; Capello et al., 2022).

For details, see https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi

In addition to its impact on digitalization, Covid-19 affected other firm-level performances, that have been investigated in parallel strands of the literature (e.g. Apedo-Amah et al., 2020). Those that have received the greatest attention are relative to the access to finance (e.g. Amin and Viganola, 2021; Khan, 2022), the role of size (Ahmad et al., 2021; Bartik et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2021; Fairlie and Fossen, 2022), and the innovation activities (Battisti et al., 2023; Han and Qian, 2020; Jin et al., 2022). The role of management is also investigated with particular reference to the gender bias issue (Hyland et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021).

They also focus on Vietnam, evidencing how size is an important factor that contributes to explain the presence of firms in online markets.

This impact has been considered relevant also within the systemic literature about innovation (e.g. Fagerberg and Srholec 2008).

By employing stratified random sampling and a common questionnaire, the ES firm-level data are nationally representative of private and non-financial firms. Since each round has a different country coverage, we merged the two datasets by using a unique firm code.

The share of firms adopting or increasing digital activity in response to the pandemic is significantly higher in 2020 than in 2021 (22% and 17%, respectively).

Since the Covid-19 Follow-up Survey was conducted by the World Bank as a follow-up survey on same enterprises covered prior to the pandemic, selecting 2019 as the pre-Covid period allows us to retain the highest number of establishments in our sample.

As further analysis we checked whether a measure of innovation output (product or process innovation) is a relevant digitalization driver as well. Results are available upon request.

Hu and Zhang (2021) find that the impact on firm performance is moderated by some aggregate level variables, such as the access to the financial system, health care system and institutions.

This is the only variable that it is not referred to the pre-pandemic period, since it accounts for the support received to face the pandemic crisis.

The questionnaire asked whether firms “spend on the acquisition of external knowledge. This includes the purchase or licensing of patents and non-patented inventions, know-how, and other types of knowledge from other businesses or organizations”.

All indexes are drawn from the World Development Indicators. For further details, see https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016/Digital-Adoption-Index

Our explanatory variables partially mirror those of Avalos et al. (2023).

In estimating the regression dividing the whole sample in small and large firms, 19 observations are dropped because of collinearity (perfect prediction) between some sector fixed effects and the dependent variable.

In order to associate the share of jobs at home for each industry of firms in our database, we used concordances between Isic at the 4-digit-level and NAICS at the 6-digit level obtained from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/Econ#Correspondences

We also run regressions including a measure of innovative output, that is represented by a dummy that indicates whether the firm has carried out a process or product innovation (“if firm introduced new product or services over last three years” or “if firm introduced new/significantly improved processes over last three years”). Results indicate that both these variables are positively related to the probability of increasing online activities. This again confirms our first hypothesis.

This result is also confirmed by the F-test (equal to 5.46, with its associated p-value 0.000) of the joint significance of our instruments in the first-stage.

References

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G. H., & Price, B. (2014). Return of the Solow paradox? IT, productivity, and employment in US manufacturing. American Economic Review, 104(5), 394–399. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.5.394

Ahmad, W., Kutan, A. M., Chahal, R. J. K., & Kattumuri, R. (2021). Covid-19 Pandemic and firm-level dynamics in the USA, UK, Europe, and Japan. International Review of Financial Analysis, 78, 101888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101888

Ali, M. E. M., & Ebaidalla, E. M. (2022). Does Covid-19 pandemic spur digital business transformation in the MENA region? Evidence from firm level data. Economic Research Forum Working Papers N. SWP20222. https://ideas.repec.org/p/erg/wpaper/swp20222.html. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Alraja, M. N., Alshubiri, F., Khashab, B. M., & Shah, M. (2023). The financial access, ICT trade balance and dark and bright sides of digitalization nexus in OECD countries. Eurasian Economic Review, 13, 177–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-023-00228-w

Amankwah-Amoah, J., Khan, Z., Wood, G., & Knight, G. (2021). Covid-19 and digitalization: The great acceleration. Journal of Business Research, 136, 602–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.08.011

Amin, M., & Viganola, D. (2021). Does better access to finance help firms deal with the Covid-19 Pandemic? Evidence from firm-level survey data. Policy Research Working Paper N. 9697, World Bank, Washington DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/6d67dbb4-8746-5f2f-8b77-e23b147709e5/content. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Añón Higón, D., & Bonvin, D. (2023). Digitalization and trade participation of SMEs. Small Business Economics, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-023-00799-7

Apedo-Amah, M. C., Avdiu, B., Cirera, X., Cruz, M., Davies, E., Grover, A., & Tran, T. T. (2020). Unmasking the impact of Covid-19 on businesses. Research Working Paper N. 9434, World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b26d46b1-969d-59f8-9c03-554e94e7a1a1/content. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Appiah-Otoo, I., & Song, N. (2021). The impact of ICT on economic growth-Comparing rich and poor countries. Telecommunications Policy, 45(2), 102082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2020.102082

Ardito, L., Raby, S., Albino, V., & Bertoldi, B. (2021). The duality of digital and environmental orientations in the context of SMEs: Implications for innovation performance. Journal of Business Research, 123(2021), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.022

Armey, L. E., & Hosman, L. (2016). The centrality of electricity to ICT use in low-income countries. Telecommunications Policy, 40(7), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2015.08.005

Avalos, E., Cirera, X., Cruz, M., Iacovone, L., Medvedev, D., Nayyar, G., & Ortega, S. R. (2023). Firms’ Digitalization during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Policy Research Working Paper, 10284. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-10284

Awiagah, R., Kang, J., & Lim, J. I. (2016). Factors affecting e-commerce adoption among SMEs in Ghana. Information Development, 32(4), 815–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669155714

Balsmeier, B., & Woerter, M. (2019). Is this time different? How digitalization influences job creation and destruction. Research Policy, 48(8), 103765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.03.010

Bartik, A. W., Cullen, Z. B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. T. (2020). What jobs are being done at home during the Covid-19 crisis? Evidence from firm-level surveys. National Bureau of Economic Research Working paper N. w27422. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27422/w27422.pdf. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Battisti, M., Belloc, F., & Del Gatto, M. (2023). COVID-19, innovative firms and resilience. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Economic Research Working Paper Series, N. 73. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4416145. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Björkdahl, J. (2020). Strategies for digitalization in manufacturing firms. California Management Review, 62(4), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620920349

Bloom, N., Fletcher, R. S., & Yeh, E. (2021). The impact of Covid-19 on US firms. National Bureau of Economic Research Worling paper N. w28314. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28314/w28314.pdf. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. M. (2003). Computing productivity: firm-level evidence. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(4), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465303772815736

Bui, L. T. H., & Nguyen, P. H. (2021). The impact of electricity infrastructure quality on firm productivity: empirical evidence from Southeast Asian Countries. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(9), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no9.0261

Capello, R., Lenzi, C., & Perucca, G. (2022). The modern Solow paradox. In search for explanations. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 63, 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2022.09.013

Cette, G., Nevoux, S., & Py, L. (2022). The impact of ICTs and digitalization on productivity and labor share: Evidence from French firms. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 31(8), 669–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2020.1849967

Chouaibi, S., Festa, G., Quaglia, R., & Rossi, M. (2022). The risky impact of digital transformation on organizational performance–evidence from Tunisia. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 178, 121571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121571

Cirera, X., Cruz, M., Davies, E., Grover, A., Iacovone, L., Cordova, J. E. L., & Torres, J. (2021). Policies to support businesses through the Covid-19 shock: A firm level perspective. The World Bank Research Observer, 36(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkab001

Coad, A., Amaral-Garcia, S., Bauer, P., Domnick, C., Harasztosi, P., Pál, R., & Teruel, M. (2023). Investment expectations by vulnerable European firms in times of COVID-19. Eurasian Business Review, 13(1), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-022-00218-z

Comin, D. A., Cruz, M., Cirera, X., Lee, K. M., and Torres, J. (2022). Technology and resilience. National Bureau of Economic Research Working paper N. w29644. https://www.nber.org/papers/w29644. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Consoli, D. (2012). Literature analysis on determinant factors and the impact of ICT in SMEs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 62, 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.016

Copestake, A., Estefania-Flores, J., & Furceri, D. (2024). Digitalization and resilience. Research Policy, 53(3), 104948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2023.104948

Crowley, F., & McCann, P. (2018). Firm innovation and productivity in Europe: Evidence from innovation-driven and transition-driven economies. Applied Economics, 50(11), 1203–1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1355543

Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., & Jäger, A. (2019). Bringing it all back home? Backshoring of manufacturing activities and the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies. Journal of World Business, 54(6), 101017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101017

Dai, R., Feng, H., Hu, J., Jin, Q., Li, H., Wang, R., & Zhang, X. (2021). The impact of Covid-19 on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from two-wave phone surveys in China. China Economic Review, 67, 101607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101607

Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

Doerr, S., Erdem, M., Franco, G., Gambacorta, L., & Illes, A. (2021). Technological capacity and firms’ recovery from Covid-19. Economics Letters, 209, 110102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2021.110102

Fairlie, R., & Fossen, F. M. (2022). The early impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on business sales. Small Business Economics, 58, 1853–1864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00479-4

Fagerberg, J., & Srholec, M. (2008). National innovation systems, capabilities and economic development. Research Policy, 37(9), 1417–1435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.06.003

Gaglio, C., Kraemer-Mbula, E., & Lorenz, E. (2022). The effects of digital transformation on innovation and productivity: Firm-level evidence of South African manufacturing micro and small enterprises. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 182, 121785.

Gal, P., Nicoletti, G., Renault, T., Sorbe, S., & Timiliotis, C. (2019). Digitalisation and productivity: In search of the holy grail–Firm-level empirical evidence from EU countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers N. 1533. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/5080f4b6-en. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Geginat, C., & Ramalho, R. (2018). Electricity connections and firm performance in 183 countries. Energy Economics, 76, 344–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.08.034

Gupta, P., Seetharaman, A., & Raj, J. R. (2013). The usage and adoption of cloud computing by small and medium businesses. International Journal of Information Management, 33(5), 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.07.001

Hameed, M. A., Counsell, S., & Swift, S. (2012). A meta-analysis of relationships between organizational characteristics and IT innovation adoption in organizations. Information and Management, 49(5), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2012.05.002

Han, H., & Qian, Y. (2020). Did enterprises’ innovation ability increase during the Covid-19 pandemic? Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Asian Economics Letters, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.46557/001c.18072

Hu, S., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and firm performance: Cross-country evidence. International Review of Economics and Finance, 74, 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2021.03.016

Hyland, M., Karalashvili, N., Muzi, S., and Viganola, D. (2021). Female-owned firms during the Covid-19 crisis. Accessible at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7456467c-ac55-5aac-898a-2abe5d1bffd9/content. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Janzen, B., & Radulescu, D. (2022). Effects of Covid-19 related government response stringency and support policies: Evidence from European firms. Economic Analysis and Policy, 76, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.07.013

Jeon, B. N., Han, K. S., & Lee, M. J. (2006). Determining factors for the adoption of e-business: The case of SMEs in Korea. Applied Economics, 38(16), 1905–1916. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840500427262

Jin, X., Zhang, M., Sun, G., & Cui, L. (2022). The impact of Covid-19 on firm innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Finance Research Letters, 45, 102133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102133

Jordaan, J. A. (2023). Firm level characteristics and the impact of Covid-19 -19: Examining the effects of foreign ownership and international trade. The World Economy, 46(7), 1967–1998. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13392

Jung, J., and Gómez-Bengoechea, G. (2022). A literature review on firm digitalization: Drivers and impacts. Estudios sobre la Economía Española. Accessible at: https://documentos.fedea.net/pubs/eee/2022/eee2022-20.pdf. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Kamp, B., & Gibaja, J. J. (2021). Adoption of digital technologies and backshoring decisions: Is there a link? Operations Management Research, 14, 380–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00202-2

Kane, G. C., Palmer, D., Philips, A. N., Kiron, D., & Buckley, N. (2015). Strategy, not technology, drives digital transformation. MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte University Press, 14, 1–25.

Khan, S. U. (2022). Financing constraints and firm-level responses to the Covid-19 pandemic: International evidence. Research in International Business and Finance, 59, 101545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101545

Kohtamäki, M., Parida, V., Patel, P. C., & Gebauer, H. (2020). The relationship between digitalization and servitization: The role of servitization in capturing the financial potential of digitalization. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 151, 119804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119804

Krammer, S. M. (2009). Drivers of national innovation in transition: Evidence from a panel of Eastern European countries. Research Policy, 38(5), 845–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.01.022

Krammer, S. M. (2019). Greasing the wheels of change: Bribery, institutions, and new product introductions in emerging markets. Journal of Management, 45(5), 1889–1926. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317736588

Li, L., Tong, Y., Wei, L., & Yang, S. (2022). Digital technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their impacts on firm performance: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Information and Management, 59(8), 103689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2022.103689

Li, G., & Shao, Y. (2023). How do top management team characteristics affect digital orientation? Exploring the internal driving forces of firm digitalization. Technology in Society, 102293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102293

Liu, Y., Wei, S., & Xu, J. (2021). Covid-19 and women-led businesses around the world. Finance Research Letters, 43, 102012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102012

Marszałek, P., Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2022). Introduction: Digitalization as a Driver of the Contemporary Economy. In: Ratajczak-Mrozek, M., Marszałek, P. (eds) Digitalization and Firm Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83360-2_1

Martínez-Caro, E., Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., & Alfonso-Ruiz, F. J. (2020). Digital technologies and firm performance: The role of digital organisational culture. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 154, 119962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119962

Muzi, S., Jolevski, F., Ueda, K., & Viganola, D. (2023). Productivity and firm Exit during the Covid-19 Crisis: Cross-country evidence. Small Business Economics, 60, 1719–1760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00675-w

Myovella, G., Karacuka, M., & Haucap, J. (2020). Digitalization and economic growth: A comparative analysis of sub-saharan Africa and OECD economies. Telecommunications Policy, 44(2), 101856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101856

Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy, 48(8), 103773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.03.018

Niebel, T. (2018). ICT and economic growth–Comparing developing, emerging and developed countries. World Development, 104, 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.11.024

Pradhan, R. P., Arvin, M. B., Hall, J. H., & Bahmani, S. (2018). Causal nexus between economic growth, banking sector development, stock market development, and other macroeconomic variables: The case of ASEAN countries. Review of Financial Economics, 23(4), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2014.07.002

Rahayu, R., & Day, J. (2017). E-commerce adoption by SMEs in developing countries: Evidence from Indonesia. Eurasian Business Review, 7, 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-016-0044-6

Reuschl, A. J., Deist, M. K., & Maalaoui, A. (2022). Digital transformation during a pandemic: Stretching the organizational elasticity. Journal of Business Research, 144, 1320–1332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.088

Rodríguez, A., Hernández, V., & Nieto, M. J. (2022). International and domestic external knowledge in the innovation performance of firms from transition economies: The role of institutions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121442

Santos, S. C., Liguori, E. W., & Garvey, E. (2023). How digitalization reinvented entrepreneurial resilience during COVID-19. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 189, 122398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122398

Skoko H., Buerki, L. and Ceric, A. (2007). Empirical evaluation of ICT adoption in Australian SMEs: Systemic Approach. International Conference on Information Technology and Applications, Harbin, China, IEEE, January 15–18, pp. 9–14

Solow, R. M. (1987). We’d better watch out. New York Times Book Review, 36.

Takeda, A., Truong, H. T., & Sonobe, T. (2022). The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium enterprises in Asia and their digitalization responses. Journal of Asian Economics, 82, 101533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2022.101533

Trinugroho, I., Pamungkas, P., Wiwoho, J., Damayanti, S. M., & Pramono, T. (2022). Adoption of digital technologies for micro and small business in Indonesia. Finance Research Letters, 45, 102156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102156

Unctad (2021). Digital Economy Report 2021. Cross-border data flows and development: For whom the data flow. https://unctad.org/publication/digital-economy-report-2021. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Vargo, D., Zhu, L., Benwell, B., & Yan, Z. (2021). Digital technology use during Covid-19 -19 pandemic: A rapid review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.242

Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Dong, J. Q., Fabian, N., & Haenlein, M. (2021). Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 122, 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022

Vu, K. M. (2011). ICT as a source of economic growth in the information age: Empirical evidence from the 1996–2005 period. Telecommunications Policy, 35(4), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2011.02.008

Vu, K., Hanafizadeh, P., & Bohlin, E. (2020). ICT as a driver of economic growth: A survey of the literature and directions for future research. Telecommunications Policy, 44(2), 101922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2020.101922

Wagner, J. (2021). With a little help from my website: Firm survival and web presence in times of Covid-19-Evidence from 10 European countries. Working Paper Series in Economics N. 399. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/234588/1/wp-399-upload.pdf. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Wang, S., Cao, A., Wang, G., & Xiao, Y. (2022). The Impact of energy poverty on the digital divide: The mediating effect of depression and Internet perception. Technology in Society, 68, 101884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101884

Wooldridge (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press.

World Bank (2016). World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2016. Accessed 22 Sep 2022

Xiao, Z., Gao, J., Wang, Z., Yin, Z., & Xiang, L. (2022). Power shortage and firm productivity: Evidence from the World Bank Enterprise Survey. Energy, 247, 123479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123479

Zhang, T., Gerlowski, D., & Acs, Z. (2022). Working from home: Small business performance and the Covid-19 pandemic. Small Business Economics, 58, 611–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00493-6

Zhu, Z., Song, T., Huang, J., & Zhong, X. (2024). Executive cognitive structure, digital policy, and firms’ digital transformation. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 2579–2592. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2022.3190889

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi del Molise within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, C., Pietrovito, F. Drivers of firms’ digital activities in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Eurasian Bus Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-024-00268-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-024-00268-5