Highlights

-

An ultrathin and flexible carbon nanotubes/MXene/cellulose nanofibrils composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure was successfully fabricated via a facile alternating vacuum-assisted filtration process.

-

The composite paper exhibits excellent mechanical property and electromagnetic interference shielding performance.

Abstract

As the rapid development of portable and wearable devices, different electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials with high efficiency have been desired to eliminate the resulting radiation pollution. However, limited EMI shielding materials are successfully used in practical applications, due to the heavy thickness and absence of sufficient strength or flexibility. Herein, an ultrathin and flexible carbon nanotubes/MXene/cellulose nanofibrils composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure is constructed for EMI shielding application via a facile alternating vacuum-assisted filtration process. The composite paper exhibits outstanding mechanical properties with a tensile strength of 97.9 ± 5.0 MPa and a fracture strain of 4.6 ± 0.2%. Particularly, the paper shows a high electrical conductivity of 2506.6 S m−1 and EMI shielding effectiveness (EMI SE) of 38.4 dB due to the sandwich structure in improving EMI SE, and the gradient structure on regulating the contributions from reflection and absorption. This strategy is of great significance in fabricating ultrathin and flexible composite paper for highly efficient EMI shielding performance and in broadening the practical applications of MXene-based composite materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With the prosperity and development of electronics technology, functional electromagnetic materials and devices have been extensively used in diverse fields, ranging from household electrical appliances to military weapons [1, 2]. High-efficiency electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials are of great significance for the alleviation or elimination of electromagnetic radiation pollution that has potential detrimental effects on human health and the normal work of electronic equipment [3,4,5,6,7]. As typical carbon-based materials, one-dimensional (1D) carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and two-dimensional (2D) graphene sheets have drawn a wide of attention for EMI shielding owing to their great superiorities in lightweight and flexibility, in contrast to the old-fashioned heavy and vulnerable metal (e.g., Cu, Ni, and Ag) materials [8,9,10,11]. For example, Song et al. [4] fabricated a lightweight and conductive CNTs-multilayered graphene edge plane core–shell hybrid foam for EMI shielding using a chemical vapor deposition method. The resultant hybrid foam exhibited high EMI shielding effectiveness with more than 38.4 dB in X-band. Although many exciting advances have been made, it is still a considerable challenge for carbon-based materials to achieve a self-supported conductive network with an efficient EMI shielding performance at small thickness [12,13,14].

A novel family of 2D early transition metal carbides and/or nitrides, MXenes (Mn+1XnTx, where M represents an early transition metal, X represents C and/or N, n = 1, 2, or 3, and T is a terminating group, such as O, OH, and/or F), were firstly discovered in 2011 by the selective etching and delamination of their layered MAX phase [15,16,17,18,19]. With large specific surface area and high electrical conductivity [20,21,22,23,24,25], Ti3C2Tx MXene has recently been extensively reported as a remarkable shielding material [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. For example, Gogotsi and his co-workers firstly reported a metallically conductive Ti3C2Tx-based film with excellent conductivity (4665 S cm−1) and superior EMI shielding effectiveness (> 92 dB, 45 µm) [3]. Sun et al. [40] subsequently fabricated a highly conductive MXene/polystyrene nanocomposite with the electrostatic assembly method. The resultant nanocomposite reached a maximum EMI SE of 62 dB at a low MXene loading of 1.90 vol%. Li et al. [41] have newly reported a reduced graphene oxide/Ti3C2Tx hybrids foam with hollow core–shell architecture, which exhibits an excellent EM absorption performance. Although some impressive progress has been made, the fabrication of EMI materials with ultrathin thickness, high flexibility, and excellent EMI shielding performance is still an enormous challenge.

Cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs), which can be isolated by (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl) oxidanyl (TEMPO) oxidation and mechanical processing from wood and plants, are composed of numerous aligned β-D-(1 → 4)glucopyranose polysaccharide chains with abundant strongly intermolecular hydrogen bonds [42,43,44,45]. With excellent mechanical toughness, integrating high stiffness about 140 GPa and a lightweight character [46,47,48], CNFs have been considered as a promising emerging class of high-performance nature-derived nanomaterials [49,50,51,52]. Moreover, CNFs with a typical 1D nanofiber structure will generate less insulating contacts between conductive nanosheets, such as reduced graphene oxide nanosheets [53], boron nitride nanosheets [54], and MXene nanosheets [55]. Particularly, CNFs are globally abundant, renewable, and environmental friendly since they are extracted from plants (e.g., wood, cotton, garlic husk). Yang et al. [53] fabricated reduced graphene/cellulose nanofiber composite films with great thermal conductivity and EMI shielding performance by vacuum-assisted filtration and hydroiodic acid reduction process. Zhang et al. [56] reported the preparation of cellulose nanofibers/multiwalled carbon nanotube composite film for EMI shielding via vacuum filtration and hot-pressing method. Recently, our group has reported a highly flexible MXene/cellulose nanofiber composite paper via a vacuum-assisted filtration self-assembly process [55]. However, owing to the insulating character of cellulose, the composite paper prepared by direct mixing of MXene and cellulose nanofibrils has showed a slight reduction in the conductivity and EMI shielding performance [53, 57, 58]. Thus, it is highly desired to develop a facile synthetic strategy, which can simultaneously improve the mechanical property, electrical conductivity, and EMI shielding performance of MXene-based composite materials [59, 60].

In this work, we report an ultrathin and flexible CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure (CMC GS) for next generation of EMI shielding application by a facile alternating vacuum-assisted filtration method. The CMC GS composite paper with excellent mechanical properties shows a combination of high tensile strength and toughness. Furthermore, the CMC composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure shows a high electrical conductivity of 2506.6 S m−1 and an enhanced EMI SE of 38.4 dB. The gradient structure of the composite paper plays a crucial role in regulating its contributions from reflection and absorption, rather than its total EMI shielding effectiveness. In contrast to gradient structure, the sandwich structure possesses more favorable advantages in the improvement in EMI SE of composite paper. Thus, the novel structural design in the fabrication of ultrathin and flexible composite paper contributes to realize outstanding EMI shielding performance and will broaden the practical applications of MXene composite materials.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Materials

Lithium fluoride (LiF, ≥ 99%), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, > 99%), sodium bromide (NaBr), and sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Corporation. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37 wt%) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. CNTs (diameter 5–15 nm) were obtained from Shenzhen Nanotech Co., Ltd., of China. Ti3AlC2 powders were purchased from Jilin 11 technology Co., Ltd. The bleached softwood pulp was purchased from Donghua Pulp Factory, China. All reagents and chemicals were used as received without further purification.

2.2 Synthesis of Ti3C2 MXene Nanosheets

Ti3C2 nanosheets were synthesized according to a wet chemical etching method as previously reported by Gogotsi [3, 61]. Typically, 1 g of LiF was dissolved in 20 mL HCl (9 M) in a Teflon vessel and stirred for about 30 min at room temperature (RT). Then, 1 g of Ti3AlC2 powders was slowly added into the etchant solution and the mixture was allowed to proceed at 35 °C for 24 h under stirring. The resultant slurry was washed repeatedly using deionized (DI) water and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min until its pH reaches about 6. The black swelled clay-like sediment was re-dispersed and further exfoliated in deionized (DI) water under vigorously shaking for about 10 min. Finally, the uniform delaminated Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets suspension with a concentration of 0.5 mg mL−1 was obtained after centrifuging for 1 h at 3500 rpm.

2.3 Preparation of Single-Layered Ti3C2–CNTs Composite Paper

CNTs aqueous dispersion with a concentration of 0.1 mg mL−1 was produced by ultrasonication for 20 min in the presence of cationic surfactant CTAB. CNTs dispersion was added dropwise to Ti3C2 nanosheets suspension followed by further ultrasonication for 10 min to guarantee the complete contacts. The mixed suspension was filtered using a cellulose filter (0.22 µm in pore size) and dried at 60 °C, achieving the single-layered Ti3C2/CNTs composite paper. The weight ratios of CNTs–Ti3C2 chosen were 1:5, 1:10, and 1:15, and the resulting single-layered composite papers were denoted as CM-5, CM-10, and CM-15, respectively. In these cases, the mass of the CNTs was set as 1 mg.

2.4 Fabrication of TEMPO-Mediated Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibrils (CNFs)

CNFs were prepared using a known method [43, 62]. First, TEMPO (100 mg) and NaBr (659 mg) were added into a softwood pulp suspension (100 mL, 1 wt%) in a glass beaker. Then, 38 mL of 12% NaClO was added into the above mixture slowly at RT to initiate TEMPO-mediated oxidation. During the above oxidation process, the pH value of the mixture was maintained at 10.5 with 0.5 M NaOH until no pH variation was observed. The TEMPO-oxidized cellulose was purified by washing several times with DI water. The product slurry was re-dispersed in DI water and further treated with a blender machine. The nanofibers were separated from unexfoliated cellulose fibers with high-speed centrifugation for 30 min. Finally, the collected supernatant was further treated with a high pressure homogenizer to obtain the uniform cellulose nanofibrils dispersion. The concentration of the CNFs was regulated as 0.5 mg mL−1.

2.5 Preparation of CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs Composite Paper with Gradient and Sandwich Structure (CMC GS)

The GMT GS composite paper was prepared using an alternating vacuum-assisted filtration method. For instance, the CM-5 was firstly filtered on the filter membrane to form a thin continuous layer. Then, a CNFs (4 mg) layer was deposited on the top of CM-5 in the same way. After that, CM-10, CNFs (4 mg), and CM-15 were successively added to be deposited on their former layer. The composite paper was then dried in vacuum oven at 60 °C and peeled off from the filter membrane, yielding free-standing CMC GS composite paper. Other composite papers with gradient or/and sandwich structure can be prepared through a similar process. To make the comparison, a randomly mixed CNTs (3 mg)/Ti3C2 MXene (30 mg)/CNFs (8 mg) composite paper, which was labeled as CMC mixture, was also constructed by a similar vacuum-assisted filtration of mixed CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs dispersion.

2.6 Characterization and Measurements

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S4800, Hitachi, Japan) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Hitachi H-800, Japan) were used to characterize morphologies and microstructures of the samples. The phase compositions of the samples were analyzed by X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku D/max 2550 V, Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.54178 Å). Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was measured using a FTIR spectrometer (FTIR-7600, Lambda Scientific, Australia). The surface chemistries of the samples were characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Scientific). Nitrogen sorption measurements were obtained at − 196 °C on a Quadrasorb instrument (Quantachrome, USA) to measure the specific surface area and pore size distribution. The mechanical tests were performed at RT by a universal testing machine (Zwick Z005) equipped with a 100 N load cell. Each sample was cut into strips (10 × 30 mm2) using a knife blade, and the loading rate was set as 0.2 mm min−1. The electrical conductivity measurements were conducted at RT using a physical property measurement system (Quantum Design) with the standard four-probe method. All samples were cut into strips (2.5 × 2.0 mm2) for measurements. Four-pin probe was tightly contacted with the samples, and sheet resistance was recorded. The electrical conductivity of samples was calculated as Eq. 1:

where σ is the electrical conductivity (S cm−1), R is the sheet resistance (Ω sq−1), L and S are the length (cm) and cross-sectional area (cm2) of the measured samples, and w and t are the width (cm) and thickness (cm) of the samples.

Agilent PNA-N5244A vector network analyzer was employed to measure the electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness (EMI SE) of samples in the frequency range of 8.2–12.4 GHz on the basis of a waveguide method. The samples were cut into the rectangular shape with a dimension of 22.9 × 10.2 mm2 for measurements. The reflection (R), transmission (T), and absorption (A) coefficients were obtained by calculating the scattering parameters (S11 and S21). The total electromagnetic interference shielding values (SET) can be obtained by Eqs. 2–7:

where SER is the reflection value, SEA is the absorption value, and SEM is the multiple internal reflection value. The SEM can be negligible at the time of SET ≥ 15 dB [10, 63, 64]. To compare the effectiveness of shielding materials equitably, density and thickness of the materials were also taken into account. The related equations were described as:

The EMI shielding efficiency (%) can be obtained as Eq. 10:

3 Results and Discussion

Figure 1a schematically illustrates the preparation process of CMC GS composite paper. First, a thin continuous layer of CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene (CM) can be obtained by a vacuum-assisted filtration from a dispersed CM aqueous solution containing 1D CNTs and 2D Ti3C2 nanosheets. Subsequently, a CNFs layer deposited on the top of CM layer is obtained in the same way. Afterward, this filtration process is repeated several times alternately with various Ti3C2 contents. By this strategy, CMC GS composite paper can be facilely obtained without using any expensive equipment or toxic organic solvents, which may have an enormous potential for large-scale manufacturing. Particularly, the introduction of gradient and sandwich structure in the composite paper is in favor of the simultaneous enhancement of mechanical properties and EMI shielding performance. For purpose of comparison, a free-standing randomly mixed CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs (CMC mixture) composite paper without gradient and sandwich structure has also been produced by the direct vacuum-assisted filtration of CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs mixed dispersion.

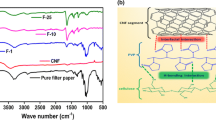

2D Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets were prepared by selectively etching Ti3AlC2 precursor (MAX phase) with HCl/LiF and further delaminating under vigorously manual shaking (Fig. S1). SEM images show that Ti3AlC2 MAX phase is a closely stacked ternary compound (Fig. S2a, b). Ti3AlC2 solid bulk changes to loosely stacked multilayered Ti3C2 MXene with a characteristic accordion-like structure (Fig. S2c, d). After further delaminating, Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets dispersion with a typical Tyndall effect was observed (Fig. 1b). As shown in X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, the representative (002) peak shifts from 9.6° to 7.0°, indicating the increased interlayer spacing from 9.20 to 12.6 Å (Fig. S3) [23, 65]. The chemical composition and surface terminations of Ti3AlC2 MAX phase and Ti3C2 nanosheets were determined by XPS (Fig. 1c). XPS results exhibit the absence of Al element and the existence of Ti–C (2p3) and Ti–O (2p3) doublets, which are in accordance with the previous reports and indicate the successful preparation of Ti3C2 nanosheets (Fig. S4) [66, 67]. The TEM image shows that delaminated Ti3C2 nanosheets with a diameter of ~ 500 nm were ultrathin and nearly transparent (Figs. 1d and S5). In addition, the dispersed CNTs aqueous solution with a concentration of 0.1 mg mL−1 has also been produced by an ultrasonic processing with the assistance of cationic surfactant CTAB (Fig. 1e) [68]. The CNTs with 5–15 nm in diameter and 15–30 µm in length (Fig. 1f) have been employed to enhance the connectivity between Ti3C2 nanosheets by forming a porous conductive network. When CNTs are added to Ti3C2 dispersion, Ti3C2 nanosheets are connected together to form numerous aggregations (Fig. S6). Figure 1g shows the homogeneously dispersed cellulose nanofibrils with Tyndall effect prepared from wood pulp with the TEMPO-mediated oxidation method. FTIR spectroscopy measurement has been performed on the CNFs, and the result is presented in Fig. 1h. The FTIR spectrum shows a broad and strong absorption band at 3446 cm−1, which is ascribed to the stretching vibration of O–H, while the strong absorption bands at 1619 cm−1 are assigned to C=O, proving the successful TEMPO-mediated oxidation process. TEM measurement has been taken to further observe the micromorphology of CNFs (Fig. 1i). TEM image shows that the diameters of CNFs are 10–50 nm and lengths are 200–500 nm. After alternant vacuum-assisted filtration of CM and CNFs, a self-supported and flexible CMC GS composite paper has been obtained. As shown in Fig. 1j, k, the composite paper can be folded into an intricate “airplane” shape without any crack or fracture, indicating excellent flexibility. Moreover, Fig. 1l shows that the thickness of the CMC GS composite paper is only 0.038 mm, which presents a great potential in miniaturized and lightweight electronic devices.

The chemical compositions of the single-layered Ti3C2 and Ti3C2–CNTs composites have been analyzed by XPS spectra. As shown in Fig. 2a, both pure Ti3C2 paper and Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper have abundant F– and O– groups, which are attributed to the fluorine and oxygen terminations on Ti3C2 nanosheets. However, the Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper has a larger C/Ti atomic ratio (1.81) than that of the pure Ti3C2 paper (1.10), owing to the addition of CNTs. Figure 2b shows the XRD patterns of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2–CNTs composite papers with different Ti3C2 contents obtained by the vacuum-assisted filtration method. The retained (002) peaks of CM-5, CM-10, and CM-15 with various Ti3C2 contents (CM-5: Ti3C2–CNTs weight ratio is 5:1; CM-10: Ti3C2–CNTs weight ratio is 10:1, and CM-15: Ti3C2–CNTs weight ratio is 15:1) indicated the well-preserved laminated structure of 2D Ti3C2 nanosheets. Moreover, with decreasing content of Ti3C2, the (002) peak shifts from 2θ = 7.0° to 5.5°, signifying that the d-spacing of Ti3C2 nanosheets clearly increases from approximately 12.6 Å of pure Ti3C2 paper to 16.0 Å of CM-5 composite paper. The increased d-spacing is attributed to the successful intercalation of the CNTs into the interlayer spaces between Ti3C2 nanosheets.

a XPS survey spectrum of the pure Ti3C2 paper and Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper. b XRD patterns of the Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper with different Ti3C2 contents. c, d N2 sorption/desorption isotherms and pore size distribution curves of pure Ti3C2 paper and Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper. e Top-view and f cross-sectional SEM images of pure Ti3C2 paper. g Top-view and h cross-sectional SEM images of Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper. i Cross-sectional SEM and EDS mapping images of CMC GS composite paper

To further explore the role of CNTs acted in Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper, N2 sorption/desorption measurements have been employed to characterize their microstructure and exposed specific surface area. Figure 2c exhibits the N2 sorption isotherms of pure Ti3C2 paper and Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper. Unlike the pure Ti3C2 paper, Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper shows a typical type-V behavior with an obvious hysteresis loop of type H2, which is resulted from the micropores generated through the introduction of CNTs between Ti3C2 nanosheets. The specific surface area calculated based on Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method shows that the pure Ti3C2 paper has a small BET surface area of 7.2 m2 g−1. On the contrary, Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper possesses a larger BET surface area of 77.2 m2 g−1. The increased BET surface area indicates that the introduction of CNTs effectively prevents the restacking effect and maximizes the accessibility of 2D Ti3C2 nanosheets. As shown in Figs. 2d and S7, besides the uniform pore size distribution of CNTs about 1.7 nm, the Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper also has a pore size distribution within the scope of 2.1–3.7 nm. In contrast, the pure Ti3C2 paper lacks these micropores and mesopores in this range. To understand the role of CNTs in Ti3C2–CNTs composite more intuitively, SEM equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscope elemental (EDS) mappings measurements is performed to characterize their morphologies and elements distribution. Figure 2e, f exhibits the top-view and cross-sectional SEM images of the pure Ti3C2 paper. Without the incorporation of CNTs, the pure Ti3C2 paper displayed a compactly stacked lamellar structure without visible pore. In contrast, after the introduction of CNTs as spacers, 2D Ti3C2 nanosheets achieve effective separation and avoided the restack, yet still connected sufficiently to form a continuous conductive network (Fig. 2g). Moreover, the Ti3C2 nanosheets have a uniform distribution in Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper, which are observed in EDS mapping results (Fig. S8). Besides, it is worth mentioning that the Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper with an undulating layered structure has numerous slit-shaped micropores (Figs. 2h and S9), which can be ascribed to the elimination of Ti3C2 nanosheets restacking by CNTs. The undulating layered structure and slit-shaped micropores of composite layer are of great significance for increasing the reflection and absorption of electromagnetic waves and further enhancing its EMI shielding performance. Single-layered CM and CNFs are used to assemble into a CMC GS composite paper in the alternant vacuum-assisted filtration process. Figure 2i shows the cross-sectional SEM and EDS mapping images, which indicate the CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure has been successfully obtained. Meanwhile, a free-standing CMC mixture composite paper with a homogeneous distribution of Ti3C2 nanosheets has been prepared as a control by the directing vacuum-assisted filtration process, which displays a uniform composite structure (Fig. S10).

Mechanical property is of great significance for EMI shielding materials, especially in the field of wearable or portable electronic devices, which need sufficient flexibility to endure mechanical deformation. It can be seen that CMC GS composite paper is stable after several foldings and being pressed with a weight of 200 g (Fig. S11). The typical tensile stress–strain curves of the pure Ti3C2 MXene, CMC mixture, and CMC GS composite paper are revealed in Fig. 3a, and the detailed data of mechanical performance are provided in Table S1. The tensile strength of the pure Ti3C2 MXene paper is only 4.9 ± 1.0 MPa, with a fracture strain of 0.9 ± 0.1% (Fig. S12). The pure Ti3C2 MXene paper with poor mechanical properties is hard to meet the requirement for practical applications. In contrast, the randomly assembled CMC mixture composite paper exhibits an improved mechanical property with a tensile strength of 94.9 ± 7.4 MPa and a fracture strain of 3.6 ± 0.2%. The significant improvement in tensile stress and strain can be attributed to the successful incorporation of CNFs, which is often used as an ideal reinforcement. Particularly, the CMC GS composite paper, which is prepared by the alternant filtration of CNFs and CM with various Ti3C2 contents, is not seen any reduction in mechanical properties. For instance, the CMC GS composite paper shows a tensile strength of 97.9 ± 5.0 MPa, a fracture strain of 4.6 ± 0.2%, a toughness of 2.1 ± 0.2 MJ m−3, and a Young’s modulus of 2.6 ± 0.2 GPa. Moreover, the mechanical performances of the Ti3C2–CNTs (WMXene/WCNTs = 5:1) composite paper and the pure CNFs paper have been also investigated (Fig. S13). Compared to Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper with poor mechanical property, the pure CNFs paper exhibits a great mechanical performance with a tensile strength of 95.7 ± 13.7 MPa and a fracture strain of 5.1 ± 1.7%. The striking contrast between fragile Ti3C2–CNTs composite paper and flexible pure CNFs paper further confirms the strengthening effect of CNFs in CMC GS composite paper.

a Tensile stress–strain curves of the pure Ti3C2 MXene, CMC mixture, and CMC GS composite paper. b SEM image and the corresponding EDS map of the fracture surface of CMC GS composite paper. c Schematic illustration of the crack propagation mode of CMC GS composite paper. d, e Electrical resistance variation of CMC GS composite paper with bending test

To investigate the fracture mechanism of the CMC GS composite paper, the SEM image for the fracture surface is shown in Fig. 3b. The surface of CMC GS composite paper shows obvious hierarchical fracture, which can be ascribed to the uneven and hierarchical distribution of CNFs and CM. Moreover, the fracture surface of the CMC GS composite paper shows a long-range crack deflection and “pull-out” mode, indicating that an additional friction exists in contact surfaces owing to the inter-limitation between CNFs and CM. EDS mapping, which has been conducted on one of the convex surfaces within the fracture surface of CMC GS composite paper, shows an even distribution of C, O, and Ti elements, confirming that the “pull-out” mode exists in stretching process. As shown in Fig. 3c, a crack propagation mode of CMC GS composite paper is proposed to explain the mechanism. When the composite paper is subjected to tensile load, the adjacent Ti3C2 nanosheets can be inclined to slide over each other, and the hydrogen bonds between the CM layer and CNFs layer are slowly destroyed, which resulted in an initial crack. Subsequently, the long-chain CNFs molecules are stretched along the drawing direction to dissipate more energy during the further stretching process, until the composite paper realizes a completely fracture. During the fracture process, the gradient and sandwich structure of the composite paper contributed to an obvious hierarchical fracture. To explore the electrical resistance variation of CMC GS composite paper under bending, the composite paper is fixed on two insulating clips and then linked with a light-emitting diode (LED) lamp. As intuitively reflected by the images in Fig. 3d, the brightness of LED lamp is not found any observable change during 100 times bending (Movie S1). In addition, we have further investigated the potential applications of CMC GS composite paper in the field of wearable designs. The composite paper is attached to index finger by conductive silver paste to monitor resistance variation after several cycles of finger bending tests. As shown in Fig. 3e, the resistance exhibits no conspicuous increase even after 100 bending cycles. The great flexibility and stable conductivity of CMC GS composite paper indicate the significant potentials in practical application to wearable or portable electronic devices.

The images of single-layered CNFs, CM-5, CM-10, and CM-15, which are used to be assembled into CMC GS composite paper, are shown in Fig. 4a. As we all know, the EMI shielding performance for the conductive materials is of great relevance to their electrical conductivity. It can be seen easily from Fig. 4b that the single-layered CNFs are an insulating material with no electrical conductivity. The single-layered CM-5 with a Ti3C2–CNTs weight ratio of 5:1 displays an electrical conductivity of 10,145.8 S m−1, which is about 10,000 times more than the requirement (1 S m−1) for EMI shielding materials in actual applications [53]. By increasing the Ti3C2–CNTs weight ratio to 15:1, the obtained single-layered CM-15 realizes an ultrahigh electrical conductivity of 23,812.0 S m−1. The excellent electrical conductivity of single-layered CM can be attributed to the continuous conductive network formed by 1D CNTs and 2D Ti3C2 nanosheets.

As expected, the superior conductivity endows the single-layered CM with excellent EMI shielding performance (Fig. 4c). The total EMI shielding performance of single-layered CM is improved with the increment in Ti3C2 content, following a parallel tendency to the variation of electrical conductivities. Moreover, all the single-layered CM samples show excellent EMI shielding effectiveness (SE) of > 30 dB over the whole X-band. In particular, comparing with a 15-mg-pure Ti3C2 paper with relative lower average EMI SE of 34 dB (Fig. S14), the single-layered CM-15 exhibits a superb EMI SE value of > 43 dB over the whole X-band with a maximum of 48 dB, which is mostly owing to the above-mentioned undulating layered structure and slit-shaped micropores of the single-layered CM. To theoretically clarify the EMI shielding mechanism of the single-layered CM, the total EMI shielding effectiveness (SETotal), microwave reflection (SER), and microwave absorption (SEA) all over the X-band have been investigated, as shown in Fig. S15. With increasing the content of Ti3C2 in single-layered CM, SEA exhibits an obvious ascending trend, whereas SER does not show any significant variation. The inferior microwave reflection and strong microwave absorption indicate an absorption dominant shielding mechanism. For example, the SETotal, SEA, and SER of the single-layered CM-15 at the frequency of 8.2 GHz are 47.6, 31.9, and 15.7 dB, respectively, which show that the contribution of reflection to total EMI SE (33%) is much lower than that from absorption (67%) (Fig. 4d).

To quantitatively analyze the influence of sandwich structure on EMI SE enhancement of composite paper, a CM–CNFs–CM composite paper with a symmetric layered structure is prepared to be acted as an electromagnetic attenuator. For instance, the string “5/0.5-4-5/0.5” in Fig. 5a refers to a three-layered composite with 5 mg Ti3C2 + 0.5 mg CNTs as the first/third layer and 4 mg CNFs as the second layer. Compared to the CNFs–CM–CNFs composite paper with same composition but different permutations of the layered structure, the CM–CNFs–CM paper with a wave-transmission intermediate layer exhibits an enhanced average EMI SE of 36 dB with a maximum of 37 dB. SETotal, SER, and SEA are calculated from the obtained scattering parameters to analyze the reason for EMI SE enhancement of CM–CNFs–CM paper. The increment in SEA of CM–CNFs–CM composite paper relative to CNFs–CM–CNFs composite paper is greater than the increment in SER, indicating that the higher effective absorption is responsible to the enhanced EMI shielding performance of CM–CNFs–CM paper (Fig. 5b). The content of CNFs between two CM layers in the CM–CNFs–CM composite paper is varied, and its effect on the EMI shielding performance is evaluated (Fig. 5c). With the CNFs content increasing from 2 to 4 mg, the average EMI SE exhibits a slight improvement from 35 to 36 dB, respectively. When the CNFs content further increased to 6 and 8 mg, the average EMI SE revealed a considerable reduction. It is mainly due to the existence of a small quantity of CNFs caused by vacuum-assisted filtration, which are involved in CM layer, and thus, the EMI performance is attenuated.

a EMI SE of composite paper with different sandwich structures in the X-band. b Comparison of SETotal, SEA, and SER of composite paper with different sandwich structures. c The EMI SE of CM–CNFs–CM composite paper with various CNFs contents in the X-band. The d EMI SE, e R, and f A of evenly distributed CM composite paper and two-layered CM composite paper with different gradient structures in the X-band

To investigate the relationship between gradient structures and the EMI SE of our composite paper, two-layered CM composite paper with various Ti3C2 contents in each layer has been fabricated with a sequential vacuum-assisted filtration method. Each composite paper is denoted with a string of numbers to conveniently represent the samples with different Ti3C2 contents. For example, the string “U10/1-S5/1” referred to two-layered composite with 10 mg Ti3C2 + 1 mg CNTs as the upper (first) layer and 5 mg Ti3C2 + 1 mg CNTs as the sublayer (second) layer. For the purpose of comparison, an evenly distributed “15/2” composite paper with 15 mg Ti3C2 + 2 mg CNTs has been fabricated via a same vacuum-assisted filtration method. As shown in Fig. 5d, although different gradient structures are presented in the samples, all these two-layered CM composite papers exhibit the similar EMI SE as SEU10/1-S5/1 ≈ SEU5/1-S10/1 ≈ SE15/2 over the whole X-band. To analyze the EMI shielding performance more intuitively, the reflection (R) and absorption (A) coefficients of different samples have also been investigated. As shown in Fig. 5e, f, the R and A of two-layered CM composite paper with two kinds of gradient structures are quite different. Moreover, the obtained R and A have a correlation of AU5/1-S10/1 > AU10/1-S5/1 and RU5/1-S10/1 < RU10/1-S5/1, which are corresponding to the representation of Fig. S16 (SEA U5/1-S10/1 > SEA U10/1-S5/1; SER U5/1-S10/1 < SER U10/1-S5/1) [38, 39, 41, 69,70,71]. These results demonstrate that the gradient structures do not show distinct effect on the total EMI shielding effectiveness but significantly affect the value of SEA and SER.

To further investigate the influence of gradient and sandwich structures on the EMI shielding performance of multilayered CMC GS composite paper, two layers of CNFs and three layers of CM with various Ti3C2 contents have been used to be assembled into a composite paper for the analysis of EMI SE. Similarly, each composite paper has a specific string to conveniently represent the samples. For instance, the string “U5/1-4-10/1-4-S15/1” refers to a five-layered composite with CM-5 (5 mg Ti3C2 + 1 mg CNTs) as the first layer, 4 mg CNFs as the second/fourth layer, CM-10 (10 mg Ti3C2 + 1 mg CNTs) and CM-5 (15 mg Ti3C2 + 1 mg CNTs) as the third and fifth layer, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6a, the CMC GS composite paper with an average EMI SE about 36.6 dB exhibits a better EMI shielding performance than the randomly mixed CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs composite paper (CMC mixture). Moreover, the five-layered CMC GS composite paper with opposite gradient structure shows nearly the same EMI SE as SEU5/1-4-10/1-4-S15/1 ≈ SEU15/1-4-10/1-4-S5/1 over the whole X-band. The highest EMI SE value of the CMC GS composite papers is 38.4 dB, indicating a high capability to block 99.99% of incident waves and only 0.01% transmission. Besides, the CMC GS composite paper with various gradient structures exhibits very different absorption coefficients, SER, and SEA, which are similar to the results of the above-mentioned CM composite paper with gradient structures (Figs. 6b and S17). Additionally, the electrical conductivity of CMC GS composite paper and randomly mixed CMC composite paper has been also investigated. It can be seen from Fig. S18 that the conductivity of CMC GS composite paper with 2506.6 S m−1 is about 5 times higher than CMC mixture paper with 546.6 S m−1. All these results revealed a similar trend with the above-mentioned two- or three-layered composite paper, indicating that the composite paper with outstanding sandwich and gradient structure has a more adjustable EMI SE and microwave-absorbing property than the randomly mixed composite paper with uniform structure. A potential mechanism of the CMC GS composite paper for EMI shielding is proposed as illustrated in Fig. 6c. As the electromagnetic waves struck the surface of CMC GS composite paper, the reflection, absorption, and transmission of electromagnetic waves can occur. Firstly, some incident waves are immediately reflected at the interface between air and the CM layer owing to their impedance mismatch, which are mainly attributed to the existence of numerous free electrons at the surface of Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets and CNTs [72,73,74]. The oriented alignment of 2D Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets and 1D CNTs along the planar direction can achieve a continuous conductive path and endow the CM layer with high conductivity [75]. The most remaining waves interact with the high electron density of Ti3C2 MXene and CNTs, giving rise to ohmic losses and attenuating the energy of waves [3, 10, 26]. Additionally, the overall laminated structure enables the CM layer to behave as a multilevel shield, which can make the waves be reflected and forth between the adjacent MXene nanosheets until completely absorbed. Meanwhile, the high conductive CM layer with undulating layered structure and slit-shaped micropores, which are formed by using CNTs as spacers, will generate multiple internal reflections to promote the dissipation of electromagnetic waves. Polarization loss is also an important way to attenuate the incident waves. Actually, the localized defects of post-etched Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets can generate an asymmetry distribution of electrons and further lead to dielectric loss. Moreover, the terminating groups (–F, =O, or –OH) on the surface of MXene nanosheets can give rise to the asymmetric distribution of charge density, which promotes the formation of local dipoles. These dipoles will rotate directionally toward the electromagnetic field and result in polarization relaxation and electromagnetic energy loss in the form of heat, which in turn enhance the overall shielding effectiveness [39, 76]. Particularly, the proposed gradient and sandwich structure of the CMC composite paper can attenuate or eliminate the internal electromagnetic waves by repeated reflection and adsorption and further achieve an excellent EMI shielding performance.

a EMI SE of randomly mixed CMC paper and CMC GS composite paper in the X-band. b The A of CMC GS composite paper with different gradient structures. c Proposed EMI shielding mechanism of the CMC GS composite paper. d Comparison of the specific EMI shielding effectiveness as a function of thickness. The numbers inside d are sample numbers listed in Table S2

The superiority of the ultrathin and flexible CMC GS composite paper over other shielding materials is emphasized by the comparison of their specific EMI shielding effectiveness (SSE), which incorporated three important parameters, that is, the EMI SE, density, and thickness. At present, metal- and carbon-based materials are the mainstream shielding materials. Although some promising progress in these materials has been made, few materials that simultaneously possess ultrathin thickness, flexibility, and excellent EMI shielding performance have been reported. As shown in Fig. 6d and Table S2, the ultrathin and flexible CMC GS composite paper shows both ultrathin thickness and high SSE and ranked the top at the comparison chart when comparing with other shielding materials, such as metal-based materials [3, 77,78,79,80], graphene [63], reduced graphene oxide [8, 81, 82], carbon nanotube [10, 83], and other MXene-based materials [27, 55] [84].

4 Conclusions

In summary, we have fabricated an ultrathin and flexible CNTs/Ti3C2 MXene/CNFs composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure by a facile vacuum-assisted filtration method. The obtained CMC GS composite paper exhibits excellent mechanical properties and an outstanding combination of high tensile strength (97.9 MPa) and toughness (2.1 MJ m−3). The results indicate that the gradient structures can make a great difference to the contributions from reflection and absorption of the composite paper, rather than their total EMI SE. Meanwhile, the sandwich structures with a different thickness enhance the EMI SE of composite paper and promote the composite paper to block more electromagnetic waves energy. The CMC composite paper with gradient and sandwich structure displays a better EMI SE of 38.4 dB than the randomly mixed CMC composite paper of 23.4 dB. Thus, the ultrathin, flexibility CMC GS composite paper with outstanding EMI shielding performance will greatly widen the practical applications in the fields of wearable or portable electronic devices.

References

M.S. Cao, Y.Z. Cai, P. He, J.C. Shu, W.Q. Cao, J. Yuan, 2D MXenes: electromagnetic property for microwave absorption and electromagnetic interference shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 359, 1265–1302 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.051

M.S. Cao, X.X. Wang, M. Zhang, J.C. Shu, W.Q. Cao, H.J. Yang, X.Y. Fang, J. Yuan, Electromagnetic response and energy conversion for functions and devices in low-dimensional materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201807398

F. Shahzad, M. Alhabeb, C.B. Hatter, B. Anasori, S.M. Hong, C.M. Koo, Y. Gogotsi, Electromagnetic interference shielding with 2D transition metal carbides (MXenes). Science 353(6304), 1137–1140 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag2421

Q. Song, F. Ye, X. Yin, W. Li, H. Li et al., Carbon nanotube-multilayered graphene edge plane core-shell hybrid foams for ultrahigh-performance electromagnetic-interference shielding. Adv. Mater. 29(31), 1701583 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201701583

S. Lee, I. Jo, S. Kang, B. Jang, J. Moon et al., Smart contact lenses with graphene coating for electromagnetic interference shielding and dehydration protection. ACS Nano 11(6), 5318–5324 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b00370

L. Huang, J. Li, Y. Li, X. Heb, Y. Yuan, Lightweight and flexible hybrid film based on delicate design of electrospun nanofibers for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Nanoscale 11(17), 8616–8625 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9nr02102g

J. Luo, L. Wang, X. Huang, B. Li, Z. Guo et al., Mechanically durable, highly conductive, and anticorrosive composite fabrics with excellent self-cleaning performance for high-efficiency electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(11), 10883–10894 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b22212

D.X. Yan, H. Pang, B. Li, R. Vajtai, L. Xu et al., Structured reduced graphene oxide/polymer composites for ultra-efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25(4), 559–566 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201403809

N. Yousefi, X. Sun, X. Lin, X. Shen, J. Jia et al., Highly aligned graphene/polymer nanocomposites with excellent dielectric properties for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Mater. 26(31), 5480–5487 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201305293

Z. Zeng, H. Jin, M. Chen, W. Li, L. Zhou, Z. Zhang, Lightweight and anisotropic porous MWCNT/WPU composites for ultrahigh performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26(2), 303–310 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201503579

X.X. Wang, J.C. Shu, W.Q. Cao, M. Zhang, J. Yuan, M.S. Cao, Eco-mimetic nanoarchitecture for green EMI shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 369, 1068–1077 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.03.164

G.M. Weng, J. Li, M. Alhabeb, C. Karpovich, H. Wang et al., Layer-by-layer assembly of cross-functional semi-transparent MXene-carbon nanotubes composite films for next-generation electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(44), 1803360 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201803360

M. Crespo, M. Gonzalez, A.L. Elias, L.P. Rajukumar, J. Baselga, M. Terrones, J. Pozuelo, Ultra-light carbon nanotube sponge as an efficient electromagnetic shielding material in the GHz range. Phys. Status Solidi R 8(8), 698–704 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.201409151

Y. Li, X. Pei, B. Shen, W. Zhai, L. Zhang, W. Zheng, Polyimide/graphene composite foam sheets with ultrahigh thermostability for electromagnetic interference shielding. RSC Adv. 5(31), 24342–24351 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ra16421k

M. Naguib, M. Kurtoglu, V. Presser, J. Lu, J. Niu, M. Heon, L. Hultman, Y. Gogotsi, M.W. Barsoum, Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 23(37), 4248–4253 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201102306

A. Lipatov, H. Lu, M. Alhabeb, B. Anasori, A. Gruverman, Y. Gogotsi, A. Sinitskii, Elastic properties of 2D Ti3C2Tx MXene monolayers and bilayers. Sci. Adv. 4(6), eaat0491 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat0491

J. Wang, J. Tang, B. Ding, V. Malgras, Z. Chang et al., Hierarchical porous carbons with layer-by-layer motif architectures from confined soft-template self-assembly in layered materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 15717 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15717

Y. Ma, N. Liu, L. Li, X. Hu, Z. Zou, J. Wang, S. Luo, Y. Gao, A highly flexible and sensitive piezoresistive sensor based on MXene with greatly changed interlayer distances. Nat. Commun. 8, 1207 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01136-9

L. Ding, Y. Wei, L. Li, T. Zhang, H. Wang et al., MXene molecular sieving membranes for highly efficient gas separation. Nat. Commun. 9, 155 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02529-6

C. Zhang, B. Anasori, A. Seral-Ascaso, S.H. Park, N. McEvoy et al., Transparent, flexible, and conductive 2D titanium carbide (MXene) films with high volumetric capacitance. Adv. Mater. 29(36), 1702678 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201702678

D. Xiong, X. Li, Z. Bai, S. Lu, Recent advances in layered Ti3C2Tx MXene for electrochemical energy storage. Small 14(17), 1703419 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201703419

V.M.H. Ng, H. Huang, K. Zhou, P.S. Lee, W. Que, J.Z. Xu, L.B. Kong, Recent progress in layered transition metal carbides and/or nitrides (MXenes) and their composites: synthesis and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 5(7), 3039–3068 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ta06772g

Z. Ling, C.E. Ren, M.Q. Zhao, J. Yang, J.M. Giammarco, J. Qiu, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, Flexible and conductive MXene films and nanocomposites with high capacitance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111(47), 16676–16681 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414215111

H. Li, Y. Hou, F. Wang, M.R. Lohe, X. Zhuang, L. Niu, X. Feng, Flexible all-solid-state supercapacitors with high volumetric capacitances boosted by solution processable MXene and electrochemically exfoliated graphene. Adv. Energy Mater. 7(4), 1601847 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201601847

M.Q. Zhao, C.E. Ren, Z. Ling, M.R. Lukatskaya, C. Zhang et al., Flexible MXene/carbon nanotube composite paper with high volumetric capacitance. Adv. Mater. 27(2), 339–345 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201404140

J. Liu, H.-B. Zhang, R. Sun, Y. Liu, Z. Liu, A. Zhou, Z.-Z. Yu, Hydrophobic, flexible, and lightweight MXene foams for high-performance electromagnetic-interference shielding. Adv. Mater. 29(38), 1702367 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201702367

S. Zhao, H.B. Zhang, J.Q. Luo, Q.W. Wang, B. Xu, S. Hong, Z.Z. Yu, Highly electrically conductive three-dimensional Ti3C2Tx MXene/reduced graphene oxide hybrid aerogels with excellent electromagnetic interference shielding performances. ACS Nano 12(11), 11193–11202 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b05739

M. Han, X. Yin, H. Wu, Z. Hou, C. Song, X. Li, L. Zhang, L. Cheng, Ti3C2 MXenes with modified surface for high-performance electromagnetic absorption and shielding in the x-band. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8(32), 21011–21019 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b06455

M. Li, M. Han, J. Zhou, Q. Deng, X. Zhou et al., Novel scale-like structures of graphite/TiC/Ti3C2 hybrids for electromagnetic absorption. Adv. Electron. Mater. 4(5), 1700617 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.201700617

X. Li, X. Yin, M. Han, C. Song, X. Sun, H. Xu, L. Cheng, L. Zhang, A controllable heterogeneous structure and electromagnetic wave absorption properties of Ti2CTx MXene. J. Mater. Chem. C 5(30), 7621–7628 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7tc01991b

H. Xu, X. Yin, X. Li, M. Li, S. Liang, L. Zhang, L. Cheng, Lightweight Ti3C2Tx MXene/poly(vinyl alcohol) composite foams for electromagnetic wave shielding with absorption-dominated feature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(10), 10198–10207 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b21671

Z. Zhou, J. Liu, X. Zhang, D. Tian, Z. Zhan, C. Lu, Ultrathin MXene/calcium alginate aerogel film for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6(6), 1802040 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201802040

R. Bian, G. He, W. Zhi, S. Xiang, T. Wang, D. Cai, Ultralight MXene-based aerogels with high electromagnetic interference shielding performance. J. Mater. Chem. C 7(3), 474–478 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8tc04795b

R. Liu, M. Miao, Y. Li, J. Zhang, S. Cao, X. Feng, Ultrathin biomimetic polymeric Ti3C2Tx MXene composite films for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(51), 44787–44795 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b18347

G. Zhao, H. Lv, Y. Zhou, X. Zheng, C. Wu, C. Xu, Self-assembled sandwich-like MXene-derived nanocomposites for enhanced electromagnetic wave absorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(49), 42925–42932 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b16727

M. Vural, A. Pena-Francesch, J. Bars-Pomes, H. Jung, H. Gudapati et al., Inkjet printing of self-assembled 2D titanium carbide and protein electrodes for stimuli-responsive electromagnetic shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(32), 1801972 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201801972

C. Xiang, R. Guo, S. Lin, S. Jiang, J. Lan et al., Lightweight and ultrathin TiO2–Ti3C2Tx/graphene film with electromagnetic interference shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 360, 1158–1166 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.10.174

X. Li, X. Yin, S. Liang, M. Li, L. Cheng, L. Zhang, 2D carbide MXene Ti2CTx as a novel high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding material. Carbon 146, 210–217 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2019.02.003

P. He, X.X. Wang, Y.Z. Cai, J.C. Shu, Q.L. Zhao, J. Yuan, M.S. Cao, Tailoring Ti3C2Tx nanosheets to tune local conductive network as an environmentally friendly material for highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Nanoscale 11(13), 6080–6088 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8nr10489a

R. Sun, H.-B. Zhang, J. Liu, X. Xie, R. Yang, Y. Li, S. Hong, Z.-Z. Yu, Highly conductive transition metal carbide/carbonitride(MXene)@polystyrene nanocomposites fabricated by electrostatic assembly for highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27(45), 1702807 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201702807

X. Li, X. Yin, C. Song, M. Han, H. Xu, W. Duan, L. Cheng, L. Zhang, Self-assembly core-shell graphene-bridged hollow MXenes spheres 3D foam with ultrahigh specific em absorption performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(41), 1803938 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201803938

A. Walther, J.V.I. Timonen, I. Diez, A. Laukkanen, O. Ikkala, Multifunctional high-performance biofibers based on wet-extrusion of renewable native cellulose nanofibrils. Adv. Mater. 23(26), 2924 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201100580

S. Dai, Y. Chu, D. Liu, F. Cao, X. Wu et al., Intrinsically ionic conductive cellulose nanopapers applied as all solid dielectrics for low voltage organic transistors. Nat. Commun. 9, 2737 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05155-y

E. Kontturi, P. Laaksonen, M.B. Linder, A.H. Nonappa, O.J. Groechel, O.Ikkala Rojas, Advanced materials through assembly of nanocelluloses. Adv. Mater. 30(24), 1703779 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201703779

W. Luo, J. Hayden, S.-H. Jang, Y. Wang, Y. Zhang et al., Highly conductive, light weight, robust, corrosion-resistant, scalable, all-fiber based current collectors for aqueous acidic batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8(9), 1702615 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702615

N. Mittal, F. Ansari, K.V. Gowda, C. Brouzet, P. Chen et al., Multiscale control of nanocellulose assembly: transferring remarkable nanoscale fibril mechanics to macroscale fibers. ACS Nano 12(7), 6378–6388 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b01084

T. Saito, R. Kuramae, J. Wohlert, L.A. Berglund, A. Isogai, An ultrastrong nanofibrillar biomaterial: the strength of single cellulose nanofibrils revealed via sonication-induced fragmentation. Biomacromoleculars 14(1), 248–253 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/bm301674e

L.J. Gibson, The hierarchical structure and mechanics of plant materials. J. R. Soc. Interface 9(76), 2749–2766 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0341

Y. Fujisaki, H. Koga, Y. Nakajima, M. Nakata, H. Tsuji et al., Transparent nanopaper-based flexible organic thin-film transistor array. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24(12), 1657–1663 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201303024

J. Huang, H. Zhu, Y. Chen, C. Preston, K. Rohrbach, J. Cumings, L. Hu, Highly transparent and flexible nanopaper transistors. ACS Nano 7(3), 2106–2113 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/nn304407r

M.M. Gonzalez del Campo, M. Darder, P. Aranda, M. Akkari, Y. Huttel, A. Mayoral, J. Bettini, E. Ruiz-Hitzky, Functional hybrid nanopaper by assembling nanofibers of cellulose and sepiolite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(27), 1703048 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201703048

R. Xiong, H.S. Kim, S. Zhang, S. Kim, V.F. Korolovych et al., Template-guided assembly of silk fibroin on cellulose nanofibers for robust nanostructures with ultrafast water transport. ACS Nano 11(12), 12008–12019 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b04235

W. Yang, Z. Zhao, K. Wu, R. Huang, T. Liu, H. Jiang, F. Chen, Q. Fu, Ultrathin flexible reduced graphene oxide/cellulose nanofiber composite films with strongly anisotropic thermal conductivity and efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Mater. Chem. C 5(15), 3748–3756 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7tc00400a

H. Zhu, Y. Li, Z. Fang, J. Xu, F. Cao et al., Highly thermally conductive papers with percolative layered boron nitride nanosheets. ACS Nano 8(4), 3606–3613 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/nn500134m

W.T. Cao, F.F. Chen, Y.J. Zhu, Y.G. Zhang, Y.Y. Jiang, M.G. Ma, F. Chen, Binary strengthening and toughening of MXene/cellulose nanofiber composite paper with nacre-inspired structure and superior electromagnetic interference shielding properties. ACS Nano 12(5), 4583–4593 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b00997

H. Zhang, X. Sun, Z. Heng, Y. Chen, H. Zou, M. Liang, Robust and flexible cellulose nanofiber/multiwalled carbon nanotube film for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57(50), 17152–17160 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b04573

J. Chen, J. Xu, K. Wang, X. Qian, R. Sun, Highly thermostable, flexible, and conductive films prepared from cellulose, graphite, and polypyrrole nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7(28), 15641–15648 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b04462

L.Q. Zhang, S.G. Yang, L. Li, B. Yang, H.D. Huang et al., Ultralight cellulose porous composites with manipulated porous structure and carbon nanotube distribution for promising electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(46), 40156–40167 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b14738

W.L. Song, C. Gong, H. Li, X.D. Chen, M. Chen et al., Graphene-based sandwich structures for frequency selectable electromagnetic shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(41), 36119–36129 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b08229

W.L. Song, L.Z. Fan, M.S. Cao, M.M. Lu, C.Y. Wang et al., Facile fabrication of ultrathin graphene papers for effective electromagnetic shielding. J. Mater. Chem. C 2(25), 5057–5064 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4tc00517a

M. Alhabeb, K. Maleski, B. Anasori, P. Lelyukh, L. Clark, S. Sin, Y. Gogotsi, Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 29(18), 7633–7644 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02847

C. Shao, H. Chang, M. Wang, F. Xu, J. Yang, High-strength, tough, and self-healing nanocomposite physical hydrogels based on the synergistic effects of dynamic hydrogen bond and dual coordination bonds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(34), 28305–28318 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b09614

Z. Chen, C. Xu, C. Ma, W. Ren, H.-M. Cheng, Lightweight and flexible graphene foam composites for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Mater. 25(9), 1296–1300 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201204196

C. Liang, Z. Wang, L. Wu, X. Zhang, H. Wang, Z. Wang, Light and strong hierarchical porous sic foam for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal insulation at elevated temperatures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(35), 29950–29957 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b07735

Q. Zhang, J. Teng, G. Zou, Q. Peng, Q. Du, T. Jiao, J. Xiang, Efficient phosphate sequestration for water purification by unique sandwich-like MXene/magnetic iron oxide nanocomposites. Nanoscale 8(13), 7085–7093 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nr09303a

H. Lin, X. Wang, L. Yu, Y. Chen, J. Shi, Two-dimensional ultrathin MXene ceramic nanosheets for photothermal conversion. Nano Lett. 17(1), 384–391 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04339

L.H. Karlsson, J. Birch, J. Halim, M.W. Barsoum, P.O.A. Persson, Atomically resolved structural and chemical investigation of single MXene sheets. Nano Lett. 15(8), 4955–4960 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00737

X. Xie, M.-Q. Zhao, B. Anasori, K. Maleski, C.E. Ren et al., Porous heterostructured MXene/carbon nanotube composite paper with high volumetric capacity for sodium-based energy storage devices. Nano Energy 26, 513–523 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.06.005

H. Lv, Z. Yang, P.L. Wang, G. Ji, J. Song et al., A voltage-boosting strategy enabling a low-frequency, flexible electromagnetic wave absorption device. Adv. Mater. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201706343

B. Wen, X.X. Wang, W.Q. Cao, H.L. Shi, M.M. Lu et al., Reduced graphene oxides: the thinnest and most lightweight materials with highly efficient microwave attenuation performances of the carbon world. Nanoscale 6(11), 5754–5761 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3nr06717c

Y. Li, B. Shen, D. Yi, L. Zhang, W. Zhai, X. Wei, W. Zheng, The influence of gradient and sandwich configurations on the electromagnetic interference shielding performance of multilayered thermoplastic polyurethane/graphene composite foams. Compos. Sci. Technol. 138, 209–216 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2016.12.002

M.S. Cao, W.L. Song, Z.L. Hou, B. Wen, J. Yuan, The effects of temperature and frequency on the dielectric properties, electromagnetic interference shielding and microwave-absorption of short carbon fiber/silica composites. Carbon 48(3), 788–796 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2009.10.028

W.L. Song, M.S. Cao, Z.L. Hou, X.Y. Fang, X.L. Shi, J. Yuan, High dielectric loss and its monotonic dependence of conducting-dominated multiwalled carbon nanotubes/silica nanocomposite on temperature ranging from 373 to 873 k in X-band. Appl. Phys. Lett. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3152764

X.Y. Fang, X.X. Yu, H.M. Zheng, H.B. Jin, L. Wang, M.S. Cao, Temperature- and thickness-dependent electrical conductivity of few-layer graphene and graphene nanosheets. Phys. Lett. A 379(37), 2245–2251 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2015.06.063

P. He, M.S. Cao, J.C. Shu, Y.Z. Cai, X.X. Wang, Q.L. Zhao, J. Yuan, Atomic layer tailoring titanium carbide MXene to tune transport and polarization for utilization of electromagnetic energy beyond solar and chemical energy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(13), 12535–12543 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b00593

M. Cao, X. Wang, W. Cao, X. Fang, B. Wen, J. Yuan, Thermally driven transport and relaxation switching self-powered electromagnetic energy conversion. Small (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201800987

J. Ma, K. Wang, M. Zhan, A comparative study of structure and electromagnetic interference shielding performance for silver nanostructure hybrid polyimide foams. RSC Adv. 5(80), 65283–65296 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra09507g

X.P. Shui, D.D.L. Chung, Nickel filament polymer-matrix composites with low surface impedance and high electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. J. Electron. Mater. 26(8), 928–934 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-997-0276-4

W.L. Song, X.T. Guan, L.Z. Fan, W.Q. Cao, C.Y. Wang, Q.L. Zhao, M.S. Cao, Magnetic and conductive graphene papers toward thin layers of effective electromagnetic shielding. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(5), 2097–2107 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ta05939e

K. Ji, H. Zhao, J. Zhang, J. Chen, Z. Dai, Fabrication and electromagnetic interference shielding performance of open-cell foam of a CU–NI alloy integrated with CNTs. Appl. Surf. Sci. 311, 351–356 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.05.067

D.X. Yan, P.G. Ren, H. Pang, Q. Fu, M.B. Yang, Z.M. Li, Efficient electromagnetic interference shielding of lightweight graphene/polystyrene composite. J. Mater. Chem. 22(36), 18772–18774 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1039/c2jm32692b

N. Agnihotri, K. Chakrabarti, A. De, Highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding using graphite nanoplatelet/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) composites with enhanced thermal conductivity. RSC Adv. 5(54), 43765–43771 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ra15674a

Y.L. Yang, M.C. Gupta, Novel carbon nanotube-polystyrene foam composites for electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano Lett. 5(11), 2131–2134 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl051375r

P. Ghosh, A. Chakrabarti, Conducting carbon black filled EDPM vulcanizates: assessment of dependence of physical and mechanical properties and conducting character on variation of filler loading. Eur. Polym. J. 36(5), 1043–1054 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-3057(99)00157-3

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771081, 51472259), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (18ZR1445100), and Beijing Forestry University Outstanding Young Talent Cultivation Project (2019JQ03014) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, W., Ma, C., Tan, S. et al. Ultrathin and Flexible CNTs/MXene/Cellulose Nanofibrils Composite Paper for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 11, 72 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0304-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0304-y