Abstract

Research examining the behavioural and psychological functioning of children and adults with sagittal synostosis (SS) is scarce, often disparate, and lacks well-matched control groups. Clinicians are therefore often unable to provide families with guidance about their child’s anticipated functioning. Social media channels were used to recruit community-based parents of children with SS, or adults with SS (n = 56) and an age- and sex-matched control group (n = 56). Families completed an online survey encompassing a range of demographic and clinical variables and a comprehensive battery of validated questionnaires. Surveys were either parent-rated (children 2 to < 5 years), both parent-rated and self-reported (children 5 to ≤ 18 years), or self-reported only (adults ≥ 19 years). Results show that for both unadjusted and adjusted (SES) analyses, children and adults were functioning at a similar level to their peers. Whilst mean parent-rated scores generally indicated that children with SS were experiencing slightly more difficulties, group differences were not statistically significant. Most adjusted Hedges’ g effect sizes were trivial (g = .10) to small (g = .20). Nonetheless, more children with SS were assessed as having clinically significant problems on each composite of the Behavior Assessment System for Children 3rd Ed. In addition, screening rates of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (18%; Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function 2) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (15%; Social Responsiveness Scale-2), in children with SS, were high. Findings suggest that children with SS should be monitored and referrals for appropriate support made readily available, as required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sagittal synostosis (SS) is the most common form of non-syndromic craniosynostosis, occurring in approximately 2–3 in 10,000 births, and seen more frequently in boys than girls (Tønne et al., 2020). The condition is characterised by the premature closure of the sagittal suture, leading to a long and narrow head-shape – hence the term scaphocephaly. Although the actual presentation of SS across individuals demonstrates considerable clinical variability (Diab et al., 2022), surgical treatment (e.g., cranial vault remodelling, strip craniectomy; Brooks et al., 2018) is typically required to improve the child’s appearance and relieve intracranial pressure, thereby allowing the brain to grow and develop normally (Chummun et al., 2016; David, 2003). The causes of SS remain unclear, with genetics (e.g., SMAD6 gene mutation), gestational exposure to environmental factors (e.g., maternal smoking, valproate medication), hormonal influences (e.g., maternal hyperthyroidism), mechanical forces (e.g., intrauterine constraint) and familial cases (in 2–6% of SS cases) all implicated (Calpena et al., 2020; Ciurea & Toader, 2009; Lajeunie et al., 1996; Wilkie et al., 2017).

To date, findings on the behavioural and psychological functioning of children and/or adults with SS are discrepant, for a recent review see: (Osborn et al., 2021a). While behaviour (e.g., hyperactivity, conduct problems, aggression) has been reported within the average range (Boltshauser et al., 2003; Chandler et al., 2020; Chuang et al., 2021; Collett et al., 2017; Hashim et al., 2014), many children with SS have presented to school-based support services seeking assistance (Peck et al., 2022) due to higher levels of behavioural problems (29%; Speltz et al., 2016). Similarly, studies that have utilised parent-rated measures of executive functioning to assess children’s ability to plan, focus their attention, and multi-task have reported scores within the average range (Chandler et al., 2020; Chuang et al., 2021; Hashim et al., 2014; Patel et al., 2014). Nonetheless, these studies have compared SS samples who have undergone different surgical techniques, numbers of operations, or ages at surgery – factors that allow for comparisons between children with SS compared to normative data, rather than their peers. The importance of comparing scores to a well-matched control group is being increasingly recognised, with scores compared to a national mean having limited value (Long et al., 2022).

Whether children with SS are experiencing higher or lower quality of life also varies dramatically across studies. Findings range between young adults with SS who report significantly higher quality of life than normative data, to studies which report no differences to normative/population data (Boltshauser et al., 2003; Kljajić et al., 2023; Mazzaferro et al., 2018; Monte et al., 2021). Again however, the use of well-matched control groups is lacking in studies examining quality of life in children/adults with SS. Lastly, few studies have examined self-reported satisfaction with appearance, with many using surgeon or proxy-rated (e.g., parental, layperson) measures to gauge appearance (Albright et al., 1996; Collett et al., 2013; Messerer et al., 2022). Ascertaining the perspective of the child/adult with SS, in addition to external opinions, is critical in developing our understanding of treatment success.

Thus, it is not clear to what extent the behavioural and psychological functioning of individuals who have been diagnosed with SS differs from their peers. Methodological limitations such as small sample sizes, minimal demographic (e.g., age, sex) and clinical (e.g., surgery status) information, non-validated or study-modified measures to assess functioning, and/or no use of comparison groups contribute to the area’s limited understanding of outcomes (Osborn et al., 2021a). Given the scarcity of research and differing findings in this area, the current study compared the behavioural (including executive functioning), social communication, quality of life and satisfaction with appearance outcomes of children and adults with SS to that of healthy age- and sex-matched controls using validated self- and parent-report measures.

Methods

Fifty-six people who had been diagnosed with non-syndromal single-suture SS and were at least 2½ years of age consented (or parents consented) to participate in the current study. Individuals were included regardless of whether they had received surgical treatment (noting that the Australian medical system includes a universal health insurance scheme that provides free or subsidised access to craniofacial surgery). Each person with SS was individually matched to a control from the general community (N = 56) of the same age and sex (matched-pairs design).

Social media was used to recruit both participant groups. Cases were sourced via a national craniosynostosis Facebook support group and various communication channels of Craniofacial Australia. Controls were recruited via paid advertisements placed on Facebook and Airtasker, and enrolled if they were an age and sex match for someone in the SS group. Both cases and controls were excluded if they had a medical condition that could substantially affect cognitive ability (e.g., epilepsy). See Fig. 1 for details on participant flow.

Customised surveys, consisting of background demographic and clinical questions and multiple validated questionnaires, were completed by both groups using the Qualtrics platform. In instances where participants were < 5 years old, surveys were completed by parents only. When participants were aged from 5 to 18 years of age (inclusive), both the parent and child completed questionnaires. Participants aged 19 years and older provided self-report data only. Each survey was accessed by a separate password-protected link that was emailed to parents (or adults if ≥ 18 yrs age). Survey links for children were provided to parents so that they could assist their child to access the self-report survey. Family units were paid $40 as recompense for their time, regardless of whether one survey (parent-rated or self-report) or two surveys (parent-rated and self-report) were completed. Families also received a brief summary of results and, when responses indicated elevated symptoms, were contacted by the study’s clinical psychologist and provided information about mental health and behavioural support options. Online written informed consent was obtained at the commencement of every survey (i.e., both parent-rated and self-report versions), before any data were collected. Study procedures were approved by the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (project approval no. HREC H-2021-138).

Measures

The Behavior Assessment System for Children, 3rd edition (BASC-3; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015) assesses behavioral and emotional problems, in addition to adaptive functioning (see Table 1). Three versions of the Parent Rating Scales (PRS) were used: PRS-P (preschool: 2½ to ≤ 5 years), PRS-C (child: 6 to ≤ 11 years) and PRS-A (adolescent: 12 to ≤ 17 years). All versions generate composite scores assessing three maladaptive behaviours: Externalizing Problems, Internalizing Problems and Behavior Symptoms Index, with a fourth composite assessing positive functioning (Adaptive Skills Composite).

Three versions of the BASC-3 Self-Report of Personality (SRP) were used to determine children/adolescent’s own feelings, attitudes, and beliefs: SRP-C (child: 8 to ≤ 11 years), SRP-A (adolescent: 12 to ≤ 17 years) and SRP-Col (college: 18 to ≤ 25 years [when studying]). Composite scores generated across all self-report versions of the BASC-3 are: Internalizing Problems, Inattention/Hyperactivity Problems, Emotional Symptoms and Personal Adjustment. The SRP-C and SRP-A also include a School Problems composite. Behaviour/feelings on the BASC are rated on a four-point scale of frequency (never/sometimes/often/almost always), with self-report versions additionally incorporating true/false response options. Higher scores indicate more problems and raw scores were converted to age-scaled T scores (M = 50, SD = 10). Composite scores have high internal consistency (parent-rated: αrange 0.88—0.98; self-report: αrange 0.86—0.97) (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015).

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) assesses an individual’s ability to guide, direct and manage their cognitive, emotional and behavioural functioning (see Table 1). One of three versions was administered, depending on participants’ ages. The BRIEF-P consists of 63 items and is rated by parents of children aged 2½ to < 5 years old (Gioia et al., 2003) and the BRIEF2 (63 items) by parents of 5 to < 18 year olds (Gioia et al., 2015). The BRIEF-A (≥ 18 years) assesses self-report data from 75 items (Roth et al., 2005). All versions use a 3-point Likert scale (never, sometimes, often), with higher scores indicating more problems. Raw scores were converted to age-scaled T scores (M = 50, SD = 10). All BRIEF versions generate an overall Global Executive Composite (GEC). Additionally, the BRIEF-P assesses: Inhibitory Self-Control (ISCI), Flexibility (FI) and Emergent Metacognition (EMI). The BRIEF2 and BRIEF-A produces two composites: Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI) and a Metacognition Index (MI). Scores on the BRIEF2 were also used to screen for the likelihood of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Gioia et al., 2020).

The Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) is a 65-item measure of symptoms associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Constantino & Gruber, 2012). Parental reports were used for preschool (2½ to ≤ 3 years) and school-age (4 to ≤ 18 years) children, with adults aged ≥ 19 years using the self-report form (see Table 1). Responses were rated on a four-point Likert scale (not true, sometimes true, often true, almost always true), with higher scores indicating more frequent problems. Two composite scores were generated: Social Communication and Interaction (SCI) and; Restricted Interests and Repetitive Behavior (RRB) in addition to an overall total score (SCI + RRB). Internal consistency for the SRS-2 is strong, with all alpha values across the preschool, school-age and adult versions falling in the range of 0.92 to 0.95.

The Paediatric Quality of Life Scale (PedsQL; Varni et al., 2001) is a health-related quality of life (HQoL) measure. Table 1 summarises the versions and scales administered according to participant age. The Toddler version was parent-rated only, with the Young Child, Child and Teen (5 to ≤ 17 years) versions parent-rated and self-report. Adults (≥ 18 years) completed self-report versions only. Items were rated in terms of their frequency using a 3 or 5-point scale depending on the rater (parent, self) and version administered. The PedsQL generates two composite scores: Psychosocial Health Summary and Physical Health Summary in addition to an overall Total Score. Higher scores indicate better HQoL. Internal consistency reliability for the Total Scale Score (α = 0.88 child, 0.90 parent report), Physical Health Summary Score (α = 0.80 child, 0.88 parent), and Psychosocial Health Summary Score (α = 0.83 child, 0.86 parent) were acceptable (Varni et al., 2001).

The Satisfaction with Appearance Scale (SWAP; Lawrence et al., 1998) assesses appearance concerns (facial and body), social discomfort and perceived social impact using 14 items on a 7-point scale (strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, neutral, somewhat agree, agree, strongly agree), with higher scores indicating lower satisfaction (see Table 1). Although initially developed for use with burns patients, it has been used with children with metopic synostosis (Osborn et al., 2021b) and with other medical conditions (Franzblau & Chung, 2015; Heinberg et al., 2007).

The 21-item self-report Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) assesses symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress experienced during the preceding week (never, sometimes, often, almost always). Adults aged ≥ 26 years completed the DASS. Adults aged ≥ 19 years who had finished studying also completed the DASS, whereas 19–25 year olds who were studying undertook the BASC-3 Col.

Cronbach’s α was calculated for questionnaire versions with sample sizes ≥ 30 in the current study, in order to measure reliability (Samuels, 2017). All composite results were considered acceptable with alpha values above 0.70 (αrange = 0.71 to 0.98).

Socio-economic Status (SES)

The Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage – which provides decile ratings for all suburbs (1 to 10, indicating low to high SES), based on a broad variety of economic and social markers (household consumption, education, employment levels, income, health) – was obtained from census data (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). These ratings were classified into low (1 – 3), medium (4 – 7) and high (8 – 10) SES.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic and clinical variables. Group differences in behavioural and psychological functioning were estimated using linear regression, with controls serving as the reference group for all analyses. The SS and community control groups were matched for age and sex on a 1:1 basis, thereby ensuring that they were comparable on these variables. Comparison of SES between the SS and Control group demonstrated no significant difference (t(109) = -0.97, p = 0.34). However, when determining a child’s developmental progress, the family’s SES should be taken into account, as variables related to SES, such as higher family income, parental education and improved health, are all associated with a child’s socio-emotional development (for a review see Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). Thus, regression estimates were adjusted for SES (deciles) and results presented both before and after controlling for SES in order to highlight the importance of considering SES when undertaking clinical assessments. Differences between groups on demographic and clinical variables were tested using independent samples t-tests (continuous data) or Pearson’s chi-square (χ2; categorical variables).

Raw scores for the BASC-3, BRIEF and SRS-2 questionnaires were converted to age-scaled standardized scores, which were then used to calculate Index scores (M = 50, SD = 10). Thus, equivalent Index scores (e.g., externalizing behaviour) obtained from the different versions of the same questionnaire (e.g., BASC-3: preschool, child, adolescent) could be analysed together. The proportion of children experiencing clinically significant problems on the BASC-3, BRIEF2 and SRS-2 was also calculated. T-scores ≥ 65 were deemed to indicate clinically significant problems, with the exception of the Adaptive Skills Composite of the BASC-3, whereby a t-score ≤ 35 indicates clinically significant problems. Descriptive statistics were calculated with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). For both unadjusted and SES-adjusted analyses, regression estimates and Hedges’ g effect sizes were calculated using Stata Statistical Software (version 17); a negative g indicating that the SS group was functioning more poorly with g = 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 indicating small, medium and large differences, respectively (Cohen, 1992). A probability value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Analyses were designed to be exploratory, therefore we did not adjust p values for multiple comparisons, nor did we consider p values to be dichotomous tests of significance. Instead, we calculated the size of the effect (Hedges’ g) across outcomes.

Supplementary data detailing subscale scores is provided for each outcome as an online resource.

Results

Summary demographic and clinical details for the SS (n = 56) and age- and sex-matched Control (n = 56) groups are provided in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the SS and Control groups on any of the demographic/clinical variables tested. The median age of cases/controls at the time of assessment was 6 years (M = 8.1; range 2 -52 yrs), with a higher proportion of males (68%) than females. Participants resided across Australia with the SS group residing in higher socio-economic areas than controls (M = 6.3 vs M = 5.7 respectively). Mothers of children with SS had also completed more years of education (MSS = 14.7 vs Mcontrol = 13.1) and were slightly older when their child was born.

The majority of mothers in both groups did not experience any complications in pregnancy, (e.g., bleeding, hyperemesis, pre-eclampsia), and whilst 7% of case and 13% of control children were born prematurely, this difference was not statistically significant. The proportion of children born by caesarean section were similar across each group (SS: 45%, Controls: 39%), with the same proportion (23%) in each group experiencing neonatal problems (e.g., bruising, jaundice). There was also no significant difference in the number of children, per group, who have ever received speech therapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, special education or mental health services.

For children in the SS group, most families reported that there was not a history of craniosynostosis in their family (82%). Equal numbers of parents (32%) and paediatricians (32%) were the first to notice the child’s unusual head shape, and none of the SS cases were detected during a prenatal ultrasound. Formal diagnoses of SS were provided by craniofacial surgeons (55%), followed by paediatricians (38%) and GPs (4%). Parents were often not sure about the severity level of their child’s SS (32%), with similar proportions reporting their child’s condition to be either moderate (27%) or severe (36%). SS was diagnosed at a mean age of 3.3 months, but ranged between 1 and 13 months, with the majority of children receiving surgical treatment (n = 54; 96%) at a mean age of 7.7 months (range 3 – 16 months). Two thirds of children (n = 37; 66%) underwent one surgical procedure only, with 13 (23%) undergoing two surgeries, and four children (7%) receiving 3 or more operations. The surgery type for the majority of children was total vault remodeling (80%), with 20% (N = 11) reporting that their child had received spring therapy and only two (4%) reporting that their child had helmet therapy. Not surprisingly, all parents noted they had consulted with craniofacial surgeons about their child, with about half (n = 30; 54%) also reporting they had discussed their child’s craniosynostosis with a paediatrician and 21 (38%) with their GP. Nine (16%) families had consulted a geneticist about their child’s SS.

Behaviour Assessment System for Children

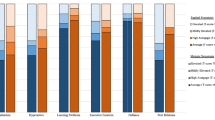

Parents of children in the case and control groups reported similar levels of problem behaviours (see Table 3, Fig. 2a). Effect sizes in analyses adjusted for SES were trivial to small (g = -0.13 to -0.22) on each of the composite indexes – Externalizing, Internalizing and Behavioral Symptoms. That is, children with SS experienced similar levels of difficulties as their healthy peers. Similarly, there was no significant difference (p = 0.64) between groups on the Adaptive Skills Composite, indicating that children with SS were functioning at similar levels to their healthy peers (g = -0.09). Nonetheless, when data were partitioned according to the level of clinically significant problems experienced by children in each group (case, control), more children with SS were experiencing greater difficulties on each of the four Composite scores (see Fig. 3).

Hedges’ g effect sizes for a Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) parent-rated data, b BASC self-reported data, c Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) parent-rated data, d Social Responsiveness Scale parent-rated data, e Paediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) parent-rated data, f PedsQL self-reported data, g Satisfaction with Appearance scale Negative g = cases have reported more problems/are poorer functioning; positive g = cases have reported fewer problems/are better functioning

Proportion of children with clincially significant problems as assessed by standardised parent-rated measures. Note: BASC-3 = Behavior Assessment System for Children 3rd Ed, Ext = Externalizing Composite, Int = Internalizing Composite, BSI = Behavioral Symptom Inventory, ASC = Adaptive Skills Composite, BRIEF2 = Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function 2nd Ed, GEC = Global Executive Composite, ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, SRS-2 = Social Responsiveness Scale 2nd Ed, ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder

BASC-3 self-reported results for children and young adults (aged 8 – 18 years; Table 3, Fig. 2b) were variable and not significant, although the small sample size likely precluded any capacity to detect significant group differences. However, once the data had been adjusted for SES, a small to moderate negative difference between cases and controls was found on the Inattention/Hyperactivity Composite (g = -0.45; p = 0.22), indicating that children with SS reported greater difficulties in this domain. There was a small positive difference (g = 0.23) on the School Problems Composite: children with SS reported having fewer difficulties in the school environment compared with controls, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.56).

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

There were no significant group differences (unadjusted and adjusted means) in parental reports of behaviours commonly thought to reflect executive functioning, despite the SS group showing evidence of slightly more problems (small negative mean differences) (see Table 3, Fig. 2c). When scores were adjusted for SES, small-moderate effect sizes were found in school-age children (5 to 16 yrs) on the BRIEF2: Behavioral Regulation Index (g = -0.38; n = 33) and Emotional Regulation Index (g = -0.46; n = 33). Results for the overall Global Executive Functioning score (children 2 ½ to 16 years; n = 53) indicate a small, non-significant difference between groups. Similarly, while the proportion of children experiencing clinically significant difficulties was high (GEC; 19%), the rate was the same for both groups (see Fig. 3).

The likelihood of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, as determined by the BRIEF2, was also not significant (χ2 = 0.13, p = 0.99) between children with SS (Ncase = 33) and their healthy peers (Ncontrol = 33). Six (18%) children in both the case and control groups were categorised as ‘likely’ to have ADHD (see Fig. 3). Five (15%) cases and four (12%) controls were categorised as ‘possibly’ having ADHD whilst the remaining children in both groups (Ncase = 22 [67%]; Ncontrol = 23 [70%]) were ‘not likely’ to have ADHD. Of the 11 cases with ‘likely’ or ‘possible’ ADHD ratings, five were further categorised as being ‘possible’ ADHD – Inattentive diagnoses and six were ‘likely’ ADHD—Combined type (i.e., a mixture of symptoms including hyperactivity, inattention and impulsivity).

Social Responsiveness Scale

The SS and Control groups did not show any significant differences on the parent-rated SRS-2 in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Parents of both groups also reported that their child was within normal limits for this measure of behaviours associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; see Table 3, Fig. 2d). Adjusted effect sizes were similar across each of the composite indexes: Social communication (g = -0.15), Restricted Interests and Repetitive Behavior (g = -0.14) and Total (g = -0.13) suggesting that, overall, the social functioning of the SS group is at a similar level to their age and sex-matched peers. Although twice as many children with SS (N = 8; 15%; age range 2 – 10 yrs) screened as being possible to have ASD on the SRS-2 than controls (N = 4; 7%; age range 5 – 7 yrs), this group difference was not significant (χ2 = 1.5, p = 0.22; see Fig. 3).

Paediatric Quality of Life Scale

The PedsQL was completed by parents (N = 53) and children (> 5 yrs; N = 36) (see Table 3). In terms of Physical Functioning, parents of children with SS reported their children were functioning significantly better in comparison to the ratings provided by parents of children in the control group, both before and after controlling for SES (adjusted g= 0.42; p=0.03; see Fig. 2e). This result was mirrored when physical functioning was self-reported (see Table 3, Fig. 2f), although the difference between the groups did not reach significance. Conversely, mean scores on the Psychosocial and Total scales differed between parents and children. Parents of children SS with SS reported their children had higher (but non-significant) quality of life compared with peers, while their children reported lower ratings than did their peers.

Satisfaction with Appearance Scale

There were no significant differences between cases and controls on the measure of satisfaction with appearance. This was the case both when parents rated their children and when children provided self-reported data. Nonetheless, parents of children with SS reported lower (small negative finding, non-significant) satisfaction with appearance (g = -0.19, p = 0.40), than parents of children in the comparison group. Conversely, the children themselves (with SS) reported higher satisfaction with appearance than their healthy peers, although once adjusted for SES, this finding decreased to a trivial group difference (g = 0.08, p = 0.84) (see Table 3, Fig. 2g).

Depression, Anxiety & Stress Scale

Two adults with SS and their matched controls completed the DASS. All scores were within the normal/subclinical range on the depression, anxiety and stress subscales (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995).

Discussion

The current study addresses a key research gap in the SS literature with few studies, to date, using a matched-pairs (age and sex) design to compare the behavioural and psychological functioning of children and adults with SS to that of individually matched controls. A comprehensive range of measures encompassing behaviour, executive functioning, social communication, quality of life and satisfaction with appearance were administered, with both parents and children providing input where possible. Our findings indicate that children who have been diagnosed with SS are generally functioning at similar levels to their peers, and within the average range for their age. However, once SES had been taken into account, children with SS were functioning slightly worse than their peers, albeit group differences were non-significant.

It is noteworthy that raw scores for all participants (cases + controls) were frequently higher than normative data, suggesting that many of the children assessed in the current study, regardless of whether they had been diagnosed with SS, were experiencing difficulties. Data collection for both groups occurred concurrently between November 2021 and November 2022, with participants recruited from similar locations across Australia. Thus, it is possible that the presence of the Covid-19 virus in Australia and it’s effect on mental health in the general community (Sicouri et al., 2023) may have impacted results, increasing the severity of problems for both groups. The current study used a wide-ranging battery of online questionnaires that targeted domains that were particularly problematic for children during Covid-19 (Westrupp et al., 2023).

In the current study, parents of children with SS consistently rated their children as experiencing slightly more problems on the BASC-3, a comprehensive broadband measure, than did parents of children in the control group. However, these differences were rarely clinically significant. Nonetheless, more parents of children with SS reported that their child was experiencing clinically significant levels of problematic behavior. These findings suggest that, from a parental perspective, while most children with SS are behaving similarly to their unaffected peers, some children struggle and therefore assistance should be readily available for families, where possible. When children rated their own behaviour and emotions, results were highly disparate: some children reported functioning well, while others were struggling. That said, the numbers of participants who were old enough to complete self-report measures in each group were small. Moreover, subscale results within the same composite indexes varied greatly (e.g., Internalizing Index: cases reported experiencing less social stress, but greater feelings of anxiety compared with controls). These issues highlight the importance of large sample sizes to ensure the results are sufficiently powered and generalisable to the wider, heterogeneous SS population.

Parental ratings of executive functioning in preschool children indicate that, at this young age (2 to < 5 years old), the behaviour of children in both the SS and Control group was not seen as being problematic. As children aged, however, parents observed that their child’s ability to self-regulate their thoughts, words, actions and emotions became more challenging, with high rates of ‘likely’ (18%) or ‘possible’ (15%) ADHD identified in children with SS. Although these rates are based on screening cut-off levels on the BRIEF2 rather than formal clinical diagnoses, they are still considerably higher than previously reported ADHD rates in Australian children (Deloitte Access Economics, 2019) or children with SS (Kljajic et al., 2021).

Similarly, high potential rates of autism (15%) were identified among children with SS in this study, based on the SRS-2 screening cut-off, despite mean parent-rated scores being within the average range for this measure. This estimate is a stark contrast to previously reported diagnosis rates of Autism in children with SS, which have ranged from 0% in a state-based Australian population study (Junaid et al., 2022), to as high as 10% in a clinical craniosynostosis study (Kljajic et al., 2021). Nonetheless, rates of autism are soaring with a recent population-based study highlighting a 500% increase in the prevalence of ASD between 2000 and 2016 (Shenouda et al., 2023). The high rates of autism and ADHD symptoms found in the current study may contribute to the social-behavioural difficulties that children encounter as they age. Children learn to interact with their peers at school, which can be difficult for children with autism as they struggle to identify and interpret social cues. Many young people with autism experience learning and communication difficulties at school, find it hard to fit in with peers and require special tuition or a counsellor/disability support person (AIHW, 2017).

Children with SS in this study were, however, functioning similarly to their peers in terms of health-related quality of life (HQoL); a result consistent with other SS research using the PedsQL (Kljajić et al., 2023). Notably, parents gave their children higher HQoL ratings than their children did for the same subscales, across all of the measured domains. This divergence in parent–child data highlights the importance of multi-rater measures in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of the lived experiences of children.

Lastly, no differences were found between those with SS and their peers in terms of satisfaction with appearance; a finding echoed by Salokorpi et al. (2019) in their study examining young adults with SS. Although scores for the SWAP were higher when the measure was self-reported by children/adolescents (≥ 8 yrs old), concerns were primarily about body shape (e.g., chest, arms for boys)—not head shape. Recent research has also reported few parental concerns about head shape, or the appearance of the scar, when comparing surgery techniques in seven year old children with SS (Chowdhury et al., 2023). This finding suggests that, subsequent to surgical treatment, children and adults with SS are equally satisfied with their appearance as their peers.

The current study fills a gap in the literature because it focuses specifically on the social-behavioural characteristics of children with SS. The study’s strengths include the comprehensiveness of assessments, a large sample size, well-matched controls and multi-raters (parent + self-report) where possible. Study limitations include the reliance on parental reports for clinical information, although we note that many parents were knowledgeable about when and what treatments their child had undergone. Recruitment for both groups was undertaken via social media, thereby introducing self-selection bias as a risk for both case and control groups, and limiting generalizability—as it would with other recruitment mechanisms such as email invitations or poster displays. Additionally, while online recruitment is known to increase geographic diversity, it may impact samples by connecting with patient groups that are concerned about their child’s condition or functioning (Benedict et al., 2019). Utilising social media did, however, enable us to reach families that were no longer in contact with hospital systems and to gain representation from all states and territories in Australia. Lastly, future research should incorporate multi-raters (e.g., parent, teacher, peers, self-report), as multiple perspectives are invaluable for examining nuances in how the child is feeling and/or behaves.

Overall, the behavioural and psychological functioning of children with SS is similar to their peers, albeit with slightly lower scores. This finding is generally consistent with other research that reports average scores within the normal range for the child’s age. Given the reported high rates of behavioural and psychological problems (e.g., ADHD, ASD) across both groups of children, referral for appropriate support for all who are experiencing difficulties should be considered.

References

Albright, A. L., Towbin, R. B., & Shultz, B. L. (1996). Long-term outcome after sagittal synostosis operations. Pediatric Neurosurgery, 25(2), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1159/000121101

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA); State Suburb (SSC) Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2017). Autism in Australia. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/autism-in-australia/contents/autism. Accessed 9/2/2023.

Benedict, C., Hahn, A. L., Diefenbach, M. A., & Ford, J. S. (2019). Recruitment via social media: Advantages and potential biases. Digital Health, 5, 2055207619867223.

Boltshauser, E., Ludwig, S., Dietrich, F., & Landolt, M. A. (2003). Sagittal craniosynostosis: Cognitive development, behaviour, and quality of life in unoperated children. Neuropediatrics, 34(6), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-44667

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Brooks, E. D., Beckett, J. S., Yang, J., Timberlake, A. T., Sun, A. H., Chuang, C., & Persing, J. A. (2018). The etiology of neuronal development in craniosynostosis: A working hypothesis. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 29(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004040

Calpena, E., Cuellar, A., Bala, K., Swagemakers, S.M.A., Koelling, N., McGowan, S. J., ... Genomics England, R. (2020). SMAD6 variants incraniosynostosis: Genotype and phenotype evaluation. Genetics in Medicine, 22(9), 1498–1506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-0817-2.

Chandler, L., Allam, O., Park, K.E., Smetona, J., Gabrick, K.S., Wu, R.T., ... Couture, D.E. (2020). Spring-assisted strip craniectomy versus cranial vault remodeling: Long-term psychological, behavioral, and executive function outcomes. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 31(7), 2101–2105.

Chowdhury, A.-M., Patel, R., Silva, A. H. D., Dunaway, D. J., Ong, J., Hayward, R., & James, G. (2023). Sagittal synostosis: Does choice of intervention and its timing affect the long-term aesthetic and neurodevelopmental outcome? A single-institution study of 167 children. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 31(2), 169–178.

Chuang, C., Chaunzwa, T.L., Wu, R., Singh, A., Patel, A., Yang, J.F., ... Mayes, L.C. (2021). Long-term neurocognitive outcomes in sagittal synostosis: The impact of reoperation. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 32(1), 58–61.

Chummun, S., McLean, N. R., Flapper, W. J., & David, D. J. (2016). The management of nonsyndromic, isolated sagittal synostosis. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 27(2), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000002363

Ciurea, A. V., & Toader, C. (2009). Genetics of craniosynostosis: Review of the literature. Journal of Medicine and Life, 2(1), 5–17.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Collett, B.R., Gray, K.E., Kapp-Simon, K.A., Birgfeld, C., Cunningham, M., Rudo-Stern, J., ... Speltz, M.L. (2013). Laypersons’ ratings of appearance in children with and without single-suture craniosynostosis. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 24(4), 1331–1335. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182997885.

Collett, B.R., Kapp-Simon, K.A., Wallace, E., Cradock, M.M., Buono, L., & Speltz, M.L. (2017). Attention and executive function in children with and without single-suture craniosynostosis. Child Neuropsychology, 23(1), 83-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2015.1085005.

Constantino, J.N., & Gruber, C.P. (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2) [Manual]. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

David, D. J. (2003). Advances in the management of the craniosynostoses. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 73(11), 949–957. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02825.x

Deloitte Access Economics. (2019). The social and economic costs of ADHD in Australia: Report commissioned by and prepared for the Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA).

Diab, J., Flapper, W., Grave, B., Abou-Hamden, A., Anderson, P., & Moore, M. (2022). The many faces of sagittal synostosis: A novel classification and approach to diagnosis. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 33(1), 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000008086

Franzblau, L., & Chung, K. C. (2015). Psychosocial outcomes and coping after complete avulsion traumatic brachial plexus injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.911971

Gioia, G.A., Espy, K.A., & Isquith, P.K. (2003). BRIEF-P: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gioia, G.A., Isquith, P.K., Guy, S.C., & Kenworthy, L. (2015). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (2nd Edition ed.). Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gioia, G.A., Isquith, P.K., Guy, S.C., & Kenworthy, L. (2020). BRIEF2 ADHD Form. Florida, USA: PAR.

Hashim, P.W., Patel, A., Yang, J.F., Travieso, R., Terner, J., Losee, J.E., ... Persing, J.A. (2014). The effects of whole-vault cranioplasty versus strip craniectomy on long-term neuropsychological outcomes in sagittal craniosynostosis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 134(3), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000000420.

Heinberg, L. J., Kudel, I., White, B., Kwan, A., Medley, K., Wigley, F., & Haythornthwaite, J. (2007). Assessing body image in patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): Validation of the Adapted Satisfaction with Appearance Scale. Body Image, 4(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.11.002

Junaid, M., Slack-Smith, L., Wong, K., Bourke, J., Baynam, G., Calache, H., & Leonard, H. (2022). Association between craniofacial anomalies, intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder: Western Australian population-based study. Pediatric Research, 92, 1795–1804. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02024-9

Kljajic, M., Maltese, G., Tarnow, P., Sand, P., & Kölby, L. (2021). Children treated for nonsyndromic craniosynostosis exhibit average adaptive behavior skills with only minor shortcomings. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 147(2), 453–464.

Kljajić, M., Maltese, G., Tarnow, P., Sand, P., & Kölby, L. (2023). Health-related quality of life of children treated for non-syndromic craniosynostosis. Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, 57, 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/2000656X.2022.2147532

Lajeunie, E., Le Merrer, M., Bonaïti-Pellie, C., Marchac, D., & Renier, D. (1996). Genetic study of scaphocephaly. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 62(3), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19960329)62:3%3c282::Aid-ajmg15%3e3.0.Co;2-g

Lawrence, J., Heinberg, L., Roca, R., Munster, A., Spence, R., & Fauerbach, J. (1998). Development and validation of the satisfaction with appearance scale: Assessing body image among burn-injured patients. Psychological Assessment, 10(1), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.1.64

Long, A. S., Hauc, S. C., Junn, A. H., Meyer, C., Mayes, L., Persing, J. A., & Alperovich, M. (2022). IQ Assessment in craniofacial neurocognitive studies: Interpreting results relative to evidence-based systematic analysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000004405

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation.

Mazzaferro, D. M., Naran, S., Wes, A. M., Magee, L., Taylor, J. A., & Bartlett, S. P. (2018). Quality of life in adults with nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 141(6), 1474–1482. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000004408

Messerer, M., Cottier, R., Vandenbulcke, A., Belouaer, A., Daniel, R. T., Broome, M., & Cossu, G. (2022). Aesthetic results in children with single suture craniosynostosis: Proposal for a modified Whitaker classification. Child’s Nervous System. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-022-05678-2

Monte, T. M., Denadai, R., Raposo-Amaral, C. A., Ghizoni, E., & Raposo-Amaral, C. E. (2021). Long-term morphologic changes on sagittal synostosis patients who underwent a modified Pi technique. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 32(1), 55–57.

Osborn, A. J., Roberts, R. M., Dorstyn, D. S., Grave, B. G., & David, D. J. (2021a). Sagittal synostosis and its association with cognitive, behavioral, and psychological functioning: A meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 4(9). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21937.

Osborn, A. J., Roberts, R. M., Mathias, J. L., Anderson, P. J., & Flapper, W. J. (2021b). Cognitive, behavioral and psychological functioning of children and adults with conservatively managed metopic synostosis. Child Neuropsychology, 27(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2020.1817356

Patel, A., Yang, J.F., Hashim, P.W., Travieso, R., Terner, J., Mayes, L.C., ... Persing, J.A. (2014). The impact of age at surgery on long-term neuropsychological outcomes in sagittal craniosynostosis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 134(4), 608e-617e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000000511.

Peck, C.J., Junn, A., Park, K.E., Khetpal, S., Cabrejo, R., Singh, A., ... Persing, J.A. (2022). Longitudinal outpatient and school-based service use among children with nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 150(6), 1309–1317. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000009678.

Reynolds, C.R., & Kamphaus, R.W. (2015). Behavior assessment system for children (3rd Edition ed.). Bloomington, MN: Pearson Clinical Assessment.

Roth, R., Isquith, P., & Gioia, G. (2005). Behavior rating inventory of executive function - adult version (BRIEF-A), (Vol. 20). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Salokorpi, N., Savolainen, T., Sinikumpu, J. J., Ylikontiola, L., Sándor, G. K., Pirttiniemi, P., & Serlo, W. (2019). Outcomes of 40 nonsyndromic sagittal craniosynostosis patients as adults: A case-control study with 26 years of postoperative follow-up. Operative Neurosurgery, 16(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opy047

Samuels, P. (2017). Advice on reliability analysis with small samples - revised version Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319165684_Advice_on_Reliability_Analysis_with_Small_Samples_-_Revised_Version. Accessed 9/3/2023.

Shenouda, J., Barrett, E., Davidow, A.L., Sidwell, K., Lescott, C., Halperin, W., ... Zahorodny, W. (2023). Prevalence and disparities in the detection of autism without intellectual disability. Pediatrics, 151(2), e2022056594.

Sicouri, G., March, S., Pellicano, E., De Young, A.C., Donovan, C.L., Cobham, V.E., ... Hudson, J.L. (2023). Mental health symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674221090174.

Speltz, M. L., Collett, B. R., Wallace, E. R., & Kapp-Simon, K. (2016). Behavioral adjustment of school-age children with and without single-suture craniosynostosis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 138(2), 435–445. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000002383

Tønne, E., Due-Tønnessen, B. J., Wiig, U., Stadheim, B. F., Meling, T. R., Helseth, E., & Heimdal, K. R. (2020). Epidemiology of craniosynostosis in Norway. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 26(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.1.PEDS2051

Varni, J.W., Seid, M., & Kurtin, P.S. (2001). PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care, 39(8), 800–812. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006.

Westrupp, E., Bennett, C., Berkowitz, T., Youssef, G.J., Toumbourou, J., Tucker, R., ... Karantzas, G. (2023). Child, parent, and family mental health and functioning in Australia during COVID-19: Comparison to pre-pandemic data. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 32(2), 317–330.

Wilkie, A. O. M., Johnson, D., & Wall, S. A. (2017). Clinical genetics of craniosynostosis. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 29(6), 622–628. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000542

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank J Bednarz, who assisted with the statistical analyses.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This work was supported by a grant from Craniofacial Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing or conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osborn, A.J., Roberts, R.M., Dorstyn, D.S. et al. Behavioural and Psychological Functioning of Children and Adults with Sagittal Synostosis. J Pediatr Neuropsychol 9, 183–199 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-023-00149-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-023-00149-1