Abstract

Traditional agency theory predicts that when a large company is trading solvently, shareholders will align their interests with those of the directors, but that this may also mean that when the company is financially distressed, directors will prefer shareholder interests to those of the creditors (even if there is no residual value for the shareholders in the company). Both the law and the market respond to this problem, and to date the situation has been held in some sort of approximate balance. However, this article examines the consequences of alignment of shareholder and director interests when a large private equity company is in financial distress, in light of the debt restructuring which is likely to be in contemplation and the type of director who is often retained. It argues that in these cases directors may have an incentive to support creditors’ debt restructuring plans, and, paradoxically, the closer the alignment of their interests and those of the shareholders when the company is trading solvently, the greater this incentive to prefer creditors may be (even if there is still a residual interest for the shareholders in the company). The implications of this for the law and for the market are explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Considerable ink has been spilt, over a considerable period of time, on the question of whether, and the extent to which, the law should intervene to regulate the duties of directors. Part of this literature focuses on so-called agency problems in large and larger mid-cap companies. An agency problem may arise when a person (the principal) is reliant on another (the agent) to perform some role on his behalf and the interests of the principal and the agent diverge, so that the agent is not motivated to act in the principal’s best interest. The literature on agency problems in large (ordinarily publicly traded) companies is itself divided into two distinct strands. First, the literature explores the problems which may arise if shareholder and directorial incentives are not aligned when a solvent company is trading, the costs which this may generate and the role which the law can play in reducing these costs by aligning shareholder and director interests.Footnote 1 The second strand of the literature explores agency problems which can arise between shareholders and creditors when a company is in financial distress, the costs which can arise and the role which the law can play in reducing these costs by protecting creditor interests when there is doubt that all claims will be repaid.Footnote 2

Most of the literature analyses the relative merits of controlling directorial behaviour in distress on the assumption that shareholders will take steps to align their interests with those of the directors when the company is trading solvently, with the result that directors may prefer shareholder interests in financial distress. Indeed, in this view, the greater the alignment of shareholder and director interests in good times, the greater the risk that directors will prefer shareholder interests over creditor interests in financial distress, even when shareholders have no residual economic interest in the company. Although scholars disagree over the extent of the issue, the appropriate solutions to it, and whether other considerations prevail,Footnote 3 most seem to consider it the issue at hand.

This article reveals a more complex account in modern financial markets and argues that, in certain cases, directorial incentives now militate against shareholder interests, in favour of creditor-led restructuring plans and creditor interests in financial distress. Moreover, and perhaps paradoxically, it argues that the greater the alignment of shareholder and director interests in good times, the greater this preference for creditor-led restructuring plans may be in distress. Using the English market as an example, it develops a more nuanced account of agency problems and agency costs in modern debt restructuring, implicating not only shareholders, directors and creditors but also complex relationships between directors and shareholders, senior and junior financial creditors, and (perhaps intuitively unlikely) director/shareholder/creditor alliances.

The article proceeds as follows. It begins with a review of the existing literature on the shareholder-director incentive problem in publicly traded companies, and the traditional English legal and market response. It explores how this relates to the so-called shareholder-creditor agency problem which arises when one of these companies is in financial distress, and the traditional response of English law and the market to this issue. It then examines the private equity model of share ownership, and analyses the impact of this model on directorial behaviour. It explores a more complex web of shareholder/creditor/director relationships and revisits the connection between the steps taken by shareholders to address agency problems in good times and directorial incentives in distress. Having considered the impact of both the new agency analysis and the new market environment on the traditional view, it makes some recommendations for law and for the market. The article then concludes.

2 The Traditional View

2.1 The Shareholder-Director Agency Problem

In their seminal 1932 book, Berle and Means identified the widespread dispersal of share ownership in US firms, and the separation of the owners from the managers who run the businesses but have a negligible ownership interest in them.Footnote 4 This wide dispersal of share ownership occurs to a greater extent in some jurisdictions than in others, but it occurs in all developed economies to some extent.Footnote 5 Two problems present themselves. First, an agency problem may arise where shareholder and directorial incentives are not aligned. Shareholders seek wealth in the stock market, while directors seek utility in the labour market. Thus, directors may have a preference for ‘perks’ such as a fast car or lavish client entertainment, for leisure activities rather than hard work (shirking), for a lower level of risk than shareholders (because their human capital is all tied up in one firm) or for different time preferences than shareholders (short-term rewards rather than long-term return—although this last is controversial).Footnote 6 Secondly, if share ownership is dispersed, it gives rise to a problem of collective action in controlling the agent directors.Footnote 7 As soon as share ownership is spread amongst a wide group, different actors may have different preferences, giving rise to a problem of coordination.

English company law offers a variety of mechanisms to deal with these agency problems.Footnote 8 For example, section 172(1) of the Companies Act 2006 provides that a director must act in the way he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole, having regard to the non-exhaustive list of factors set out in the section. The Companies Act also imposes other relevant duties on directors,Footnote 9 and enables a simple majority of shareholders to vote to remove a director.Footnote 10 These rules seek to incentivise directors to have regard for the interests of their principal (the shareholders) in two ways: first, by threatening court-imposed sanctions if shareholder interests are ignored, and, secondly, by providing shareholders with the power to remove recalcitrant directors.

Nonetheless, in practice, the English courts have remained reluctant to interfere in commercial decision making on a number of grounds: that judges have neither sufficient experience nor knowledge to decide commercial matters;Footnote 11 that judicial interference will slow up the pace of commerce; that it is important for the commercial world to know that decisions which are reached will not be upset except in the clearest of cases; and that commercial decision making often requires a balancing exercise between competing considerations in which the court should not interfere.Footnote 12 Moreover, the Charterbridge test requires that, in determining whether the director has acted in the best interests of the company, the English court will ask itself whether the director acted in what the director, rather than the court, thought to be in the best interests of the company, and that the question for the court to consider is whether the director honestly believed that his act or omission was in the best interests of the company. Only if the director failed to turn his mind to a relevant factor, or the court does not believe the director’s assertions, will it apply an objective standard.Footnote 13 Thus, often, ‘law stays at the margins of what boards are doing by focusing on formalities, process and liability’,Footnote 14 so that there are limits to the effectiveness of English commercial law in eliminating agency problems. Exercise of shareholder powers such as removal, on the other hand, requires both coordination and observation of the behaviour complained of. Both of these may prove challenging.

As a result, shareholders in large corporates in England have not relied entirely on the law to control agency problems, but have developed their own mechanisms to influence directorial behaviour. Two of these are particularly relevant to our account. First, large listed companies do not necessarily seek directors based on particular industry expertise, but rather based on their skills in communicating with investors and the market.Footnote 15 Indeed, on his appointment, Dave Lewis, the current Chief Executive of the English supermarket chain Tesco, proudly announced ‘I’ve never run a shop in my life’.Footnote 16 Executive directors in large UK listed companies are often what we might call ‘professional’ directors: directors who do not see their career progression in terms of a particular sector or business, but rather in terms of progressing through the ranks of listed companies. A small group of so-called institutional investors (mainly pension funds and insurance companies) has traditionally exerted substantial control over these listed company directors.Footnote 17 Although the mix of shareholders in listed corporate Britain is changing rapidly, already encompassing a far more diverse range of institutional shareholders, such as overseas investors, hedge funds, activist investors, sovereign wealth funds and others,Footnote 18 a core group of institutional domestic shareholders remains a regular investor in the market.Footnote 19 Directors of UK listed companies expect to have repeated interactions with these key players throughout their professional lives, and to focus on their reputation with this influential cohort.Footnote 20 Thus, concern for reputation in the market for directors strongly incentivises the UK listed company executive director to focus on shareholder value.

UK listed companies also retain professional, non-executive directors (in the literature often referred to as ‘independent’ or ‘outside’ directors). These directors are appointed for the purpose of remaining independent of those involved in the management of the firm.Footnote 21 They will usually have a portfolio of interests and will perform this role on each of the boards on which they sit. These non-executive directors are also highly motivated by concerns for their reputation with shareholders. They expect to rotate through a number of appointments as they vacate seats on boards at the end of their term, and are dependent on reputation for their ability to gain another appointment. In the listed company space, given that directors are likely to be dependent on the chairman and chief executive for an appointment,Footnote 22 a record of looking after shareholder interests is likely to be an essential qualification for recruitment. They are also likely to serve on other boards and to be concerned with reputation insofar as it affects their other positions.

The second market control mechanism for the shareholder/director agency problem relevant to this account is close alignment of incentives through pay. There are two principal forms of incentive alignment through pay. The first is to continue to pay the director in cash, but to tie a percentage of the pay package to results (performance pay). The second is to give managers shares in the company in addition to salary and cash bonuses.Footnote 23 In this way, management’s incentives are aligned closely with those of the shareholder body, and management is motivated to act in the shareholders’ best interests. Although executive compensation generally, and equity compensation schemes in particular, have recently been the subject of critical enquiry and may create their own agency issues in healthy companies,Footnote 24 they remain an important plank in the bastion against directorial self-interest.Footnote 25 In their path-finding work in the 1970s, Jensen and Meckling described the sum of reputational bonding and monitoring expenditure, and the residual loss which arises to the extent that directorial self-interested behaviour is not completely eliminated, as ‘agency costs’.Footnote 26

2.2 The Shareholder-Creditor Agency Problem

Close alignment of shareholder and directorial interest through reputational bonding and incentive pay generates another agency problem, this time between shareholders and creditors, when a company is distressed.Footnote 27 When the company faces financial trouble, directors’ alignment with shareholder interests may cause them to take ever more reckless action in an attempt to turn things around: action which may also be in the best interests of shareholders, who have no residual interest in the company if it becomes insolvent, but which will not be in the best interests of creditors. This excessively risky behaviour may impose costs on the company and its creditors if it is not eliminated.

English common law responds to this problem by imposing a shift in the duties of directors, when a company is financially distressed, from acting in the best interests of shareholders towards acting in the interests of creditors.Footnote 28 Whilst the comparatively recently codified duties of directors of a company incorporated in England and Wales require the directors to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members, section 172(3) of the Companies Act 2006 preserves the common law requirements to consider the interests of creditors when the firm is distressed.Footnote 29 The English common law position is supported by statute, particularly section 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986 and the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986. Section 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986, known as the wrongful trading test, provides that a director may be personally liable if he should have known that the company had arrived at the point at which there was no reasonable prospect it would avoid insolvent liquidation, and he did not then take every step with a view to minimising potential loss to creditors.Footnote 30 The standard prescribed is that of the reasonable director, enhanced by any particular knowledge, skill and experience that director may have.Footnote 31 The disqualification regime threatens miscreant directors with disqualification from acting as a director for a period of between 2 and 15 years.Footnote 32

Once again there are significant enforcement challenges. Insofar as the common law duties are concerned, the English courts have continued to be aware of the risk of intervention in commercial decision making, not only for all the reasons already identified but also, in this area, specifically because of the risk of hindsight bias. Thus, they have commented that it is not the function of the court to second-guess the decisions which businessmen take in the moment,Footnote 33 and have made clear that they will approach the duties of directors of a financially distressed company in the same way as the Charterbridge approach discussed above.Footnote 34 In other words, provided the director adduces evidence that he was acting in good faith, and turned his mind to the question of creditor interests, the decision will not be impugned. Moreover, it is not clear precisely when the duty to creditors arises,Footnote 35 and, when it does arise, whether it supplants or joins the duty to shareholders.Footnote 36

Furthermore, in the case of wrongful trading, it is challenging to establish when the duty to avoid wrongful trading arises, what it is that the directors should conclude and how the ‘reasonable prospect’ test should be applied, so that in reality great weight will be put on the written record for the purposes of assessing liability under section 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986. Moreover, the general approach to contribution appears to be compensatory rather than penal and, until recently, claims were limited to only certain types of office holder (liquidators) who frequently faced practical difficulties in raising finance to bring a claim, so that the benefits of a claim might not easily be said to outweigh the risks.Footnote 37 Notwithstanding reform in the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, extending the ability of liquidators to bring wrongful trading claims to administrators (another type of insolvency office holder) and entitling office holders to sell wrongful trading claims, scholars wonder whether incentives to bring claims will be increased.Footnote 38

We also find the disqualification regime beset with enforcement challenges. Disqualification is a state-enforced regime but the Secretary of State is reliant on information from office holders in deciding whether to act.Footnote 39 Office holders, in their turn, have limited incentives to be pro-active given that no proceeds for the estate flow from a successful disqualification.Footnote 40 Judges have exhibited disqualification reticence in all but the most serious of cases (particularly where negligence is implicated),Footnote 41 and questions have been raised about governmental resources to pursue disqualification cases.Footnote 42 Significant reforms to this regime are also being introduced through the Deregulation Act 2015 and the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015,Footnote 43 although some of the underlying problems continue to subsist.

Nonetheless, whatever the odds of a successful claim, the professional executive or non-executive director in a UK listed company is unlikely to regard the risk of censure worth the putative benefit of excessively risky behaviour. Even judicial or state criticism is likely to have a significant impact on the ability for directors in this group to find work. Thus, whatever the enforcement weaknesses of the common law and statutory regime, the professional director is likely to take the regime seriously so that it will influence corporate governance in UK listed companies in periods of financial distress.Footnote 44 Listed company directors are also likely to be well advised, and will thus be well informed about the legal rules and their legal responsibilities. For all these reasons, directors of UK listed companies are likely to be mindful of their legal obligations to creditors in financial distress, to some extent addressing shareholder-creditor agency problems.

Given, however, that English corporate law does not eliminate the shareholder-creditor agency problem completely, creditors have developed their own market mechanisms to reduce total agency cost. Jensen and Meckling highlighted the role of covenants imposed in the lending contract as a market control mechanism.Footnote 45 Through the covenants, lenders can monitor firm performance and, at an early sign of distress, can bring management to the table, control its risk-taking behaviour and, if necessary, force the company into an insolvency process to realise the assets and distribute the proceeds. Thus, creditors are able to strengthen their position through the lending contract. Following Jensen and Meckling, expenditure on negotiating covenants and monitoring, together with any residual loss to creditors to the extent that excessively risk-taking behaviour is not eliminated completely constitute the agency costs of debt. When the monitoring provisions of the lending contract are coupled with the shift towards creditor interests in English law, they balance the strong incentives which UK listed company directors have to protect their reputation in the market for directors and to protect their equity value at risk, so that the benefit of these self-help steps in tackling risk-taking behaviour and reducing the residual loss to creditors makes it worth bearing the cost of taking them. Total agency costs are reduced and, overall, the system could be said to be in an approximate balance or equilibrium. But, as we shall see, new market changes may destabilise this delicate eco system.

3 Market Changes

3.1 Private Equity

Thus far, we have described only one type of large company with widely dispersed shareholders. However, since the 1990s, the private equity industry has exploded onto the scene in the UK. The private equity firm regularly raises funds from widely dispersed shareholders. Each fund is invested in the private equity limited partnership (with the private equity firm providing the general partner). The limited partnership will acquire companies (‘portfolio companies’) either in public company takeovers or through auctions or private purchases, funding the purchase through comparatively small amounts of equity and significant amounts of debt (so that these purchases are known as leveraged buyouts or ‘LBOs’). The private equity firm then trades the business for a few years, with a view to selling it to a new buyer or re-listing it on the stock exchange and returning a profit to the investors.Footnote 46 The private equity model thus transforms widely dispersed share ownership into a new form of concentrated share ownership.

The private equity director is often hired for his particular expertise in a given market.Footnote 47 There may not be a broad market for this director’s skills, and attractive vacancies may emerge comparatively infrequently. The director’s ‘payoff’ may be highly dependent on the results of the particular firm in which he invests time and effort, and he may attach more weight to direct compensation than to reputation when compared with the professional director. Private equity houses are adept at aligning their interests and those of management in pursuing a clear business plan to achieve an exit from the investment in a relatively short period of time (often somewhere between 5 and 7 years after purchase),Footnote 48 and both parties are offered the prospect of a relatively quick but significant financial return.Footnote 49 Management in private equity situations is likely to have a significant proportion of its remuneration tied up in shares in the business, and often work with single-minded focus towards the proposed exit. We might expect, therefore, to find the shareholder-creditor agency problem to be particularly acute when a private equity portfolio company is in financial distress. But, as we shall see, changes in restructuring practice produce new and perhaps intuitively surprising agency problems in these companies.

3.2 Restructuring Practice

The traditional view of the shareholder-creditor agency problem in distress in widely held public companies was developed at a time when a few large deposit-taking or ‘clearing’ banks provided the bulk of finance to corporate Britain.Footnote 50 Financial covenants in the lending agreement tested, on an ongoing basis or periodically, whether the borrower’s financial health was being maintained (for example, by testing that balance sheet value was maintained at not less than a stated amount, or that the ratio of financial indebtedness to tangible net worth remained within prescribed levels).Footnote 51 If the testing process revealed that a financial covenant had been breached, the borrower and the lender(s) (ordinarily a single bank or a small group of banks) would meet to discuss what to do next. Typically, the banks would commission an accountancy firm to produce an independent business review (IBR) of the company’s financial and operational position. The banks would then determine whether a restructuring was possible, or whether the company should be placed in a formal insolvency process and (ideally) its business and assets or (at least) its assets sold, and the proceeds distributed.Footnote 52

Until comparatively recently, if a restructuring could be agreed in the UK, it involved extension of repayment dates, relaxation of covenant levels or of other aspects of the testing regime, and sales of non-core parts of the business in order to pay down some debt. Agreement would usually be reached out of court and by contract.Footnote 53 Where a restructuring could not be agreed, management failings were likely to be implicated in the collapse, for example, because managers had expanded firms too quickly, had failed to recognise changed market conditions, had not demonstrated sufficient commitment to the business, or lacked knowledge or ability.Footnote 54 Directors knew that if measures could not be agreed, or were not successful, formal insolvency would follow, and they would lose their jobs and their equity in the company. Crucially, their currency in the market for directors would likely be depreciated, making it very difficult for them to secure another role. In other words, their incentives were closely aligned with those of the shareholders in preferring continuation of the company wherever possible, the shareholder-creditor agency problem was broadly as described in the first part of this article and the agency cost analysis holds good.

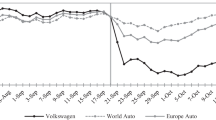

In the last decade, private equity companies have raised more debt relative to the amount of equity invested than a typical listed company.Footnote 55 Often this debt is divided into layers or ‘tranches’, with some senior debt which commands a relatively low interest rate but which ranks first on an insolvency, and some debt ranking behind the senior debt on an insolvency (in other words, junior or subordinated to it) but commanding a higher interest rate.Footnote 56 During the recent recession, many operationally sound companies struggled to meet large debt service bills, or found that they could not refinance at the same multiple of their earnings when their debt matured.Footnote 57 Whereas a traditional restructuring of a large corporate did not implicate a restructuring of its debt (other than, possibly, extending maturity dates or amending terms such as financial covenant testing ratios), in these highly leveraged situations the most obvious solution was often to swap some of the financial liabilities for equity. In this way, lenders retained a residual interest in the firm and were able to capture any improvement in financial performance after the deleveraging, but the company was not saddled with ongoing debt liabilities which absorbed all of its free cash.

Moreover, a specialist market for investing in distressed situations is now well established.Footnote 58 Distressed debt investors buy debt at a discount to the face value of the debt, with a view to profiting when a debt restructuring is in prospect or is implemented. As a result, if a traditional bank lender is not convinced by the case for a restructuring but the distressed debt investors are, the bank is able to sell its debt claim at a predictable loss rather than taking the risk of insolvency enforcement and sale. Once those who do not want to support the company have traded out and those who see profit in a restructuring have traded in, the debt-for-equity swap can be implemented.Footnote 59 These distressed debt investors require timely and significant profit to meet the expectations of their own investors.Footnote 60 Some will sell quickly, once debt prices trade up on the prospect of a restructuring. Others will have a longer-term plan to hold the equity and make significant profit by re-listing the company or selling it once the market or the business has recovered. But even these longer-term investors will expect to achieve an exit in a comparatively small number of single digit years.

This new environment has several implications for the agency analysis. First, although the new environment brings new challenges (such as identifying who is holding the company’s debt),Footnote 61 arguably the prospects for a successful rehabilitation of the business after a debt restructuring implemented via legal process have improved from the days when funding was provided exclusively by bank lenders and the only options were amendment of loan terms or a sale of the business and assets and distribution of the proceeds. Crucially, the debt-for-equity swap will immediately ease the company’s liquidity pressures and will often free up cash for investment and growth. Directors may therefore see a debt restructuring as improving the company’s prospects and, if they can retain their jobs, implicitly their own. Secondly, the cause of the financial difficulty is often an inappropriate capital structure imposed by the investors in the business and not the directors, so that the directors are not implicated in the company’s problems,Footnote 62 Creditors may therefore be content for the directors to continue in post after the debt restructuring. Thirdly, it becomes necessary to value the business in order to determine how far down the capital structure equity should be distributed in the debt-for-equity swap, and in what proportions.Footnote 63 This valuation will be dependent on management’s business plan and projections for the company,Footnote 64 and, as we have seen, the English court pays deference to the commercial judgment of the directors. Finally, distressed debt investors will wish to align their interests with those of management in order to secure a successful exit, just as the original shareholders did before them. For all of these reasons, the directors may be offered a significant equity stake, ranking behind less debt, if the debt-for-equity swap is implemented.

Here is the nub of the matter. Whilst in the traditional analysis the director’s only hope of making a recovery was to renegotiate the company’s lending arrangements, retain his equity, ranking behind a significant amount of debt, and maintain his currency in the market for directors and thus the ability to be appointed to another listed company role, many modern debt-for-equity swap restructuring proposals may offer the industry-specialist director a more attractive solution. If the director takes the new equity on offer in the new restructuring, he will have a good stake in a deleveraged company, ranking behind considerably less debt; possibly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a significant amount of money. English insolvency law does not prohibit this allocation of equity to the director, and the delicate balance maintained between shareholders and creditors in the listed company situation achieved through the incentive to retain equity and concern for reputation on one side of the scales and common law and statutory obligations to creditors on the other has fundamentally shifted. In many highly leveraged private equity situations, the director’s equity stake is more likely to have value if the initial valuation of the business is as low as possible, so that as much debt (ranking ahead of the equity) as possible is written down.Footnote 65 There is little to incentivise a director to think about shareholders and/or junior creditors at all when market re-employment prospects might be low and his financial and career returns are best improved by backing the senior creditors’ horse. This imposes new agency costs on the shareholders to the extent that the directors prefer the creditor-led restructuring plan and the low valuation which supports it, even where the shareholders may be able to argue for a residual economic interest in the company. In this situation, if the law mandates replacement of shareholder interests with creditor interests before the onset of insolvency, the scales are simply tipped more dramatically in favour of creditors. Paradoxically, the greater the extent to which shareholders have aligned their interests with those of the director through equity compensation when times are good, the greater the director’s incentive to prefer a creditor-led restructuring plan (and a low valuation for the company) in distress.

We might expect that the private equity sponsor would rely on independent or nominee appointees to the portfolio company board to reduce total agency costs. As these directors rely on the private equity house for appointment and are unlikely to be offered compensation in a creditor-led debt restructuring, they might be expected to favour the interests of the private equity sponsor over creditor interests, and to argue for a more optimistic business plan supporting a higher valuation for the company. However, in their survey, Cornelli and Karakaş find evidence of few independent directors in private equity companies.Footnote 66 They cite Kaplan and Strömberg’s suggestion that modern private equity firms ‘often hire professionals with operating backgrounds and an industry focus’.Footnote 67 It is the case that sometimes the private equity sponsor will place its own nominee, or nominees, on the board of directors. However, Cornelli and Karakaş have shown that private equity firms will not always put a nominee on the board because the private equity sponsor does not have limitless resources and because there is a trade-off between the costs of making the appointment and the benefits of doing so.Footnote 68 Whether a nominee is appointed or not may depend, amongst other things, on the complexity of the case, the strategy for the investment and the approach to governance of the particular private equity house (Cornelli and Karakaş remind us that ‘it might be misleading to think about a private equity modus operandi with the assumption that all private equity firms have the same approach’).Footnote 69 Moreover, and significantly, Cornelli and Karakaş find a lower level of private equity sponsor nominees on boards where ‘leverage’, or the ratio of debt to equity, is higher.Footnote 70 They tentatively conclude that these may be what they call ‘financial engineering deals’: in other words, deals where success is dependent on the capital structure chosen for the acquisition, with high levels of debt at low rates of interest, rather than on bringing about operational change. Yet, we also know that high leverage may increase the prospect that the company will face financial distress in the future.Footnote 71

Significantly, Cornelli and Karakaş also show that where the sponsor does have a nominee on the board, management still tends to command more votes.Footnote 72 In other words, the private equity nominee does not control the board, and even if the private equity sponsor has appointed a nominee, this is unlikely to eliminate the risk of self-interested decision making by the majority of the board. If, once the company is distressed, shareholders exercise their powers to remove directors so as to address agency problems, they risk prompting lenders to take action to accelerate their debt and seize control of the business through an administrator, notwithstanding that the covenant breach entitling the lenders to do so may fall far short of actual cash flow insolvency absent an actual acceleration. Moreover, nominee board members may become concerned about their personal liability in a legal architecture built around the concept of a shift in duty towards creditors, so that replacement nominees are likely to require expensive indemnities, if a candidate can be found at all.Footnote 73 And the shareholders expose themselves to arguments that they have acted as so-called shadow directors of the company and that they are also responsible for wrongful trading.Footnote 74 Overall, the cost of these steps to address the agency problem may be too high relative to the prospects of eliminating creditor bias in the board’s decision-making process and, therefore, to the anticipated reduction in the shareholders’ residual loss.Footnote 75 As Easterbrook and Fischel explain, the ‘trick’ is to keep total agency costs as low as possible.Footnote 76 If one agency cost does not reduce another which it is designed to tackle, or not by much, then it will not be worth incurring.

New agency costs may also arise between different classes of financial creditor. Just as senior creditors, supported by the directors, may advance a low valuation for the company in order to grab the lion’s share of the equity from the shareholders, so senior creditors and the directors may argue that the valuation is such that the junior creditors no longer have an economic interest in the company. Junior creditors may not be able to control for this agency cost in their lending contract with the senior creditors at any price. This is because the senior creditors may only be willing to allow more debt to be raised on the basis that it is on subordinated terms, set out in a contract between the senior and junior lenders known as an intercreditor agreement. Amongst other things, it is likely that the junior creditors will have passed the power to control enforcement to a specified majority of the senior creditors, until the senior creditors have been repaid in full, and, possibly, will have agreed that they will not enforce other rights (potentially even the right to receive interest) for a period of time.Footnote 77 This issue is exacerbated by the lack of authority around the meaning of ‘interests of creditors’ in section 172(3) of the Insolvency Act 1986. Recent cases have conceptualised it as ‘creditors as a whole’.Footnote 78 Yet, the application of this standard is murky where more than one class of financial creditor is implicated, and leaves ample room for directors to justify a preference for senior creditor value as the first value at risk, where self-interest is in reality the motivating factor.

It is also worth mentioning in passing that the picture may be even more complicated than these two broad scenarios. In some cases the shareholder may regard its best chance of salvaging something from the situation to lie in injecting new liquidity into the business in the form of a new equity subscription.Footnote 79 As this will be equity in the newly deleveraged company, the shareholder hopes to profit alongside the distressed debt investors and the directors when the company is listed or sold, or another exit strategy is pursued. Yet, this can lead to quite byzantine negotiations. Where the senior lenders are leading the restructuring plan, supported by the directors, the shareholders may seek to align themselves with this group, excluding the junior creditors. Indeed, ideally the shareholder whose strategy is to make a return through a new equity injection would prefer its equity to rank behind as little debt as possible, and would prefer a deep debt-for-equity swap. In this case, a complex shareholder and senior creditor vs. junior creditor agency problem may arise, with the former group capturing directorial support for their plan and then advancing a low value for the company supported by the directors’ business plan, whilst the junior creditors maintain that they have a continuing economic interest. But in other cases it is possible that the junior creditors will have a good case for an equity allocation in the debt-for-equity swap, so that the shareholders need to obtain their support for the liquidity injection. Thus, all sorts of strategies may be in play, and it is difficult to make generalisations about how stakeholders will interact as the analysis becomes highly case specific.

3.3 Some Empirical Support

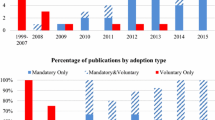

One of the challenges with research in this area is the difficulty of investigating behavioural differences, still less quantifying them. Yet, there is a risk that without any empirical research the assumptions about transactions will remain a matter of anecdote and hypothesis. In order to go some small way to addressing this issue, a hand-picked data set of restructurings of large and larger mid-cap English groups between 2008 and 2013 was built, using a variety of sources, particularly the restructuring deal lists published by Debtwire (an online provider of information on corporate debt situations), press reports, announcements from participants in the transaction and details of certain of the transactions in the European Debt Restructuring Handbook.Footnote 80 The data set comprised 52 restructuring situations. The cases were then examined to establish whether they resulted in a debt-for-equity swap, a formal insolvency process or some other outcome. Where a formal insolvency process (such as a pre-packaged administration) was used to transfer equity ownership of the business to the lenders, the transaction was classified as a debt-for-equity swap and not an insolvency proceeding.Footnote 81 Where a debt-for-equity swap, or a transaction which produced a functionally equivalent outcome, was identified, sources were reviewed to establish whether management received an equity allocation or not, or whether that was unknown. Where possible, the size of any management equity allocation was noted. Some data were cross-checked with information available on the English Companies House’s new, free Beta Service, but it often proved difficult to identify the ultimate parent company in a corporate group, and in many cases where it was identified, the ultimate parent was not incorporated in England and Wales and so did not file accounts or annual returns there. Specialist finance structures such as structured investment vehicles (SIVs) and collateralised mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) were not included in the list. Where research indicated a formal insolvency process (other than those processes used to implement a transaction functionally equivalent to a debt-for-equity swap), management was assumed to have made no return. The purpose was not to undertake a full-scale empirical study, but rather to provide just enough empirical facts to ground the discussion in this article, and the results are set out in the table below.

Company type | Outcome | Management equity allocation? | Size of management equity allocation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Debt-for-equity swap | Insolvency | Other | Yes | No | Unknown | 5–10 % | 10.1–20 % | Unknown | |

Listed | 5 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 1 | |

PE | 22 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

Other | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||||

Notwithstanding their limitations, several things are striking about the data. First, in many listed company cases the company entered a formal insolvency process. A range of other outcomes was identified, including takeovers at a low price, rescue rights issues and refinancing, but the data set included only two cases in which the directors appear to have supported a creditor-led debt-for-equity swap in a listed company. In the first of these cases, shareholders were offered the chance to vote to accept the transaction at a value which would have seen them recover 1 English penny per share. The shareholders voted against the deal, but it was implemented via a pre-packaged administration sale of the business and assets to a new company owned by the lenders, with management reported to have acquired a 20% stake in the post-restructuring equity.

The second case concerned Hibu, a yellow pages directories business in the UK. In 2013, it announced a debt-for-equity swap implemented via an insolvency sale pursuant to which large fund investors would take control and its shareholders would be wiped out. The Hibu shareholders formed an action group and wrote an open letter in which they explained that they would be asking the board to demonstrate that they had acted in shareholders’ best interests throughout the process. The letter stated:

‘… [W]e note that [the directors] have paid themselves bonuses from shareholder funds and appear to have negotiated themselves new contracts with the creditor group. We will need comfort that throughout this process it was shareholders’ interests and not self interest that was uppermost in their minds.’

A newspaper report in September 2013 listed the shareholder grievances, including that allowing the executive directors to remain in position after the shares were suspended seemed ‘too cosy’.Footnote 82 Hibu’s Chairman and its Chief Executive resigned following completion of the financial restructuring. There is evidence here both of reluctance by professional listed company directors to attract shareholder ire, and of coordinated shareholder action.

When we come to the private equity cases, the situation is very different. The overwhelming majority of cases proceeded by way of debt-for-equity swap, and in many it has been possible to identify positively a management equity allocation. In most of the cases it was challenging to determine the size of the equity allocation, although of those cases where it could be identified 5 were in the 5–10% range (most around 10%) and 1 was in a higher range. Once again, this is only a very partial picture, and the claims made for the data are not great. For example, the data do not identify when the directors were appointed to the board, their individual characteristics, the amount of debt on the balance sheet pre and post restructuring and the valuation for the company, whether the post-restructuring equity was divided into different classes of share, or the economics attaching to management’s stake. Nonetheless, notwithstanding the need to approach the data with an awareness of their limitations, they are interesting in supporting the picture that debt-for-equity swaps with an allocation of equity to management have become a regular feature of leveraged buyout restructurings. Notably, the number of formal insolvencies in this group is very low. Only two cases were identified in which the company successfully refinanced, and in one of these cases lenders were provided with some control rights.

4 Impact of Market Changes on the Traditional View

This leads us to the question of whether English corporate law should seek to reduce the agency costs of restructuring by limiting the risk of creditor bias in the board’s decision-making process. The risk that managers may be incentivised to support creditors when the firm is financially distressed if they are to receive equity in the restructured business has been identified in the English cases. In Re Bluebrook (also known as IMO Carwash), the junior creditors argued that a debt restructuring in which only senior creditors would receive equity was unfair because the value of the group’s assets was greater than the value of the senior debt.Footnote 83 Mr Justice Mann specifically noted that a majority of the board was transferring to the new group (which was to be owned by the senior lenders), with a bonus plan.Footnote 84 However, he fell back on a device commonly used to defend against agency problems: the independent director. Two of the directors were not transferring to the new group but had approved the deal.

In recent times it has been increasingly common for creditors to request that an individual with experience of financial distress is appointed to the board of a troubled company to provide advice to the other directors. But the creditors are likely to have influence regarding the identity of the appointee, and the specialist manager taking a board appointment in a period of distress is likely to be conscious of the need for repeated interaction with the creditor body.Footnote 85 Like the professional non-executive director, the ‘turnaround director’ is likely to place great currency on his reputation in the market for turnaround directors, but in this case on his reputation with the creditors rather than with the shareholders. We might, therefore, expect this group to put more weight on reputation than some of the other groups, but reputation for delivering an acceptable result for the major creditors. Even between creditor interests, an independent turnaround director may not deliver the protection which the appointment might be seen to promise. It would be a particularly courageous individual who would stand in the way of a debt restructuring which commands sufficient senior creditor and board support to be implemented, and who would advance the interests of a weaker constituency that lacked the bargaining power to protect itself. Indeed, a turnaround director who adopted this course would be wise to worry about his future employment prospects.

In Re Bluebrook, the junior lenders argued (although apparently tentatively) that the board should have considered alternative transactions which would have produced a return for the senior and the junior creditors. Mr Justice Mann expressed concern with the practical realities of the situation, which appears, in turn, to have forced Counsel for the junior lenders into arguing for a negotiating position based on the fact that the senior lenders would never have contemplated an insolvency sale, so that the board could simply have refused to take any action unless some value was attributed to the junior lenders.Footnote 86 Put in these terms, the argument looks rather stark, and Mr Justice Mann concluded: ‘This is not to say that the board had no negotiating position at all. It did not have to do whatever the senior lenders wanted. But it was not in a position to bargain for some return to other creditors if the senior lenders resisted that’.Footnote 87

Yet, even if the valuation evidence in Bluebrook could not sustain a challenge, the junior lenders’ arguments do reveal some of the difficulties with which this article is concerned. First, it is not possible to arrive at a single assumption about the way in which directors will behave when a company is financially distressed to which the law responds. Instead, what is needed is a flexible approach which can adapt to the particular circumstances of the case. Secondly, one scenario is that in a modern restructuring case the directors may have their own reasons for preferring creditors over shareholders, or certain creditor interests over others, even when shareholders or junior creditors, or both, have some economic interest in the company, so that legal rules which entitle directors to give primacy to senior creditor interests may exacerbate, rather than address, emerging agency costs. And finally, self-help measures to control the total agency costs of restructuring may be too expensive relative to their benefit or not practically available at all, so that there is a good case for corporate law to respond.

In another context, Andrew Keay has made a persuasive theoretical case for an entity maximisation and sustainability approach to directors’ duties in English law, or ‘EMS’.Footnote 88 EMS does not require directors to attempt to identify and focus on particular stakeholders in determining how to balance different options or considerations, but rather mandates a single objective of maximising the long-run value of the company. However, in doing so, directors must also have regard to ‘sustainability’, used here in the purely financial sense in which Keay uses it, involving ‘both the survival of the company, namely the company does not fall into an insolvent position from which it cannot escape, and the continuing development of the financial strength of the company’.Footnote 89 EMS would seem to offer a promising standard against which to judge directors’ decision-making in a debt restructuring.

First, where we are considering a large debt restructuring, by way of either a debt-for-equity swap or a rescue rights issue or distressed takeover of a listed company, we do want the directors to consider whether the restructuring is the best transaction for the company as a whole, or whether there is another transaction which will maximise the value of the company for a greater number of stakeholders, but which is also feasible and sustainable. In Re Bluebrook, Mr Justice Mann was sceptical that there was such a role for the directors, given the valuation evidence that was before the board and the fact that the junior lenders were well organised and arguing for themselves.Footnote 90 However, with respect, this does not provide a complete answer.

The board is the guardian of the business plan which will be fundamental to the valuation exercise. Given the evidence of this article, we should be mindful of the range of incentives which operates on directors in a modern case. We should incentivise directors, in setting the business plan, not to be so cautious that those who are rolled into the restructuring transaction receive ‘too good a deal’,Footnote 91 but at the same time not to be so optimistic that those low in the capital structure get a chance to make a recovery at the expense of the claims of those higher up, or that shareholders are persuaded to invest in a rescue rights issue when in reality there is no real equity story for the business. The entity maximisation and sustainability approach works well as a test here: in setting the business plan the directors should attempt to maximise the value of the company for all its stakeholders, but not in an excessively risky fashion. It provides directors with a clear way to think about their obligations in producing the company’s strategic plan. Crucially, at a time when it may be very difficult to identify who has an economic interest and who does not, EMS does not require directors to satisfy particular stakeholder interests where there are other, sustainable, solutions to create value for a larger number of stakeholders. It therefore also goes some way to removing directors’ preferences from the decision-making process: a defensive response that directors’ behaviour is justified in (senior) creditors’ best interests is replaced with a test which assesses ‘principled decision making independent of the personal preferences of managers and directors’ in reviewing the basis on which the directors arrived at the forecasts in the business plan.Footnote 92 Moreover, the test should work reasonably well whatever the particular incentives of the directors. This means that it is also more future-proof as the mix of shareholders in publicly traded companies in the UK continues to diversify, and some of the reputational bonding mechanisms explored in the article come under pressure in that context.

However, merely implementing a new standard without adopting a new standard of judicial scrutiny is unlikely to have any significant effect on the agency costs of restructuring. In Re Bluebrook, Mr Justice Mann expressed frustration at how late the case against the directors was put, and how weakly it was articulated.Footnote 93 Yet, we have already seen that a successful challenge is likely to require the claimant to adduce evidence that the directors acted in bad faith, and thus to challenge their honesty. This is obviously a serious allegation, which in England implicates professional conduct standards for Counsel advancing it, and appears to have resulted in allegations being made against directors in vague and half-hearted terms. It is suggested that the solution to this problem lies in the English court adopting an enhanced level of scrutiny, in lieu of the Charterbridge test, in assessing debt restructuring transactions where a majority of the board is to receive an equity allocation in the debt restructuring. Something might usefully be learnt here from the approach of the Delaware courts in the field of takeovers, where directors may also be acting out of self-interest in defending a hostile bid, or in promoting the interests of one bidder over another. Time and space do not permit a full review here, but the point with which we are particularly concerned is the court’s approach to its review. Where the circumstances are enough to suggest that director self-interest might be a motivating factor, in certain cases the Delaware courts have not required the claimant to prove, as a threshold condition, that the directors were acting in bad faith.Footnote 94 Instead, the courts have conducted an initial enquiry to establish whether the usual deference to the board’s decision making in US law should apply. This is achieved by placing the initial burden of proof on the directors to show that they complied with their duties. Applying this to a debt restructuring in which the directors are to receive an equity allocation, the English courts would require the directors to establish that they pursued an EMS approach in preparing the business plan. Notwithstanding concerns about judicial intervention,Footnote 95 we are concerned here with the production of a business plan and the selection of a particular transaction, rather than second-guessing commercial decisions made in the course of business with the benefit of hindsight. In other words, it is suggested that the worst concerns with judicial scrutiny would not apply if, where a debt-for-equity swap is proposed in which the directors are to receive an equity allocation, the directors’ obligation to prepare a business plan in a way which maximises the value of the company and is sustainable were accompanied by an enhanced level of judicial scrutiny of their decision making.

It is also suggested that shareholders should think about corporate governance issues not only for good times, but also to protect themselves against a flight of loyalty if the business becomes distressed. Paradoxically, the more closely shareholders align compensation incentives when the company is trading profitably, the more the director may be incentivised to switch allegiance if the company becomes financially distressed. Thus, the very mechanism by which shareholders reinforce loyalty in good times may hasten a switch of loyalty in bad times, at least in certain types of company. As we have seen, there will be a cost-benefit analysis to be undertaken in determining the composition of the board, so that it will not always be feasible or desirable to add independent or nominee directors to a board; and, in any event, as we have seen, unless the independent and nominee directors constitute a majority of the board, they are unlikely to significantly reduce total agency costs of restructuring.

It is suggested here that soft action in terms of ‘relationship building’ may provide part of the answer. The risk-shifting incentive arises because of the powerful single-minded focus of management on its payoff from equity incentive schemes and, it has been suggested, is greatest for industry experts for whom the exit opportunity offers perhaps a once-in-a-lifetime chance of significant financial reward. Whilst this single-minded focus can be highly effective, it is suggested here that there is also a need for shareholders to build a relationship of trust and loyalty with directors who see a long-term future with them and are thus incentivised to protect shareholder interest if the firm is wounded but not fatally so. It is suggested that detailed governance considerations will become increasingly important for private equity firms and for those who invest in them. It is also something which the more heterogeneous shareholder body in listed companies will need to get to grips with.

5 Conclusion

In a publicly traded company, shareholders face a series of agency problems because their incentives may not be the same as the incentives of the directors. English commercial law provides a range of solutions to agency problems, particularly by imposing duties on directors. However, in practice, the English courts are reluctant to second-guess directorial decision making and so the market has also developed solutions to the agency problem. A classic solution is to reinforce reputational concerns and to align shareholder and director interests through compensation. The traditional analysis shows how this close alignment of shareholder and director interests may give rise to another agency problem in financial distress: the shareholder-creditor agency problem. Put shortly, the more shareholder and director interests are aligned when the company is solvent, the greater the incentive for directors to prefer shareholder interests when the company is financially distressed (even if the shareholders have no residual economic value in the company). English law responds to this problem by imposing obligations on directors to consider creditor interests. Once again, though, there are limitations to the solutions offered by the law, and so creditors also respond to the issue by imposing covenants in the lending contract. Together, the shift in duty at law and the contractual protections balance the incentives for directors to prefer shareholder interests.

Modern cases introduce new, and complicated, dynamics. The growth of the private equity industry means that many large companies are now privately owned by private equity sponsors, and have raised significant amounts of debt relative to equity. Private equity sponsors may also have a preference for industry-specialist directors. Together these mean that both the type of director and the type of transaction which is contemplated in financial distress are likely to be different. Crucially, the restructuring plan may very well offer directors the prospect of an equity allocation ranking behind less debt, so that industry-specialist directors with few prospects of alternative employment may be incentivised to support it in circumstances where there is a still a residual interest for other financial creditors or shareholders. Paradoxically, this incentive may be greater the more closely directorial compensation incentives are aligned with those of the shareholders. Moreover, complex relationships between directors, shareholders and different classes of creditors may emerge. A limited amount of empirical evidence from English cases goes some way to supporting the thesis, although there is undoubtedly considerable further research which could usefully be done, for example, in a detailed comparison of the returns to management and the returns to different classes of creditors and to the shareholders.

Once we understand how directors may behave in a modern restructuring case, and the range of different behaviours, we may wish to revisit our approach to the duties at law of directors when a financially distressed company is undertaking a restructuring transaction. This article has suggested that we should replace tests which assume that creditor interests supplant shareholder interests or which impose a vague obligation to act in the interests of ‘creditors as a whole’, with a test (modelled on the US test) of whether the directors have sought to maximise the value of the company for all the stakeholders in preparing the business plan and projections on which the debt restructuring is based, and in pursuing the particular transaction before the court. This does not require the directors to be excessively cautious or excessively ambitious; a middle ground is required. Perhaps more significantly, this article has suggested a heightened level of judicial scrutiny when director self-interest is in prospect in a debt restructuring and, crucially, that directors’ decision making in this area should be capable of being impugned without demonstrating bad faith or a lack of honesty. The article has suggested that the worst concerns with judicial review of commercial decision making do not arise here, because we are not focused on second-guessing business decisions with the benefit of hindsight but rather on a contemporaneous review of the business plan and projections, and the decision to pursue one transaction rather than a different one. But it has also suggested that the review of directorial incentives holds lessons for all institutional shareholders, particularly in how they approach board composition and their relationships with the board.

Notes

For an excellent overview and analysis, see Enriques et al. (2009).

For an excellent overview and analysis, see Armour et al. (2009b).

In particular, as to whether the market mechanisms available to stakeholders to control for these agency problems offer sufficient protection, or whether legal intervention is also necessary. See, e.g., Keay (2003).

Berle and Means (1932).

Wymeersch (2013), at p. 124.

This list is taken from Molho (1997), at pp. 120–121.

See Armour, Hansmann and Kraakman (2009a).

Companies Act 2006, s 171(b), s 172(1), s 173(1), s 174(1), s 175(1), s 176 and s 177.

Companies Act 2006, s 168.

Lesini v Westrip Holdings Ltd [2009] EWHC 2526 (Ch); [2010] BCC 420, at [85].

Cobden Investments Limited v RWM Langport Ltd, Southern Counties Fresh Foods Limited, Romford Wholesale Meats Limited [2008] EWHC 2810 (Ch), at [754].

Charterbridge Corp. Ltd v Lloyds Bank Ltd [1969] 3 WLR 122.

Winter and Van de Loo (2013), at p. 228.

Stapledon (1996), at pp. 101–106 and 117–121.

Wood (2014).

Stapledon (1996), at pp. 33–53.

Office for National Statistics (2012).

Wymeersch (2013), at p. 115.

Stapledon (1996), at pp. 79–154, provides a detailed account of institutional shareholder involvement in the UK.

Hansmann et al. (2009), at p. 55.

Stapledon (1996), at pp. 139 and 143.

Molho (1997), at p. 122, listing a system of bonuses, profit sharing, profit-related pay, payment by commission or linking pay to the company share price.

Bozzi et al. (2013), at p. 298.

Jensen and Meckling (1976), at p. 304.

Ibid., at p. 345.

See Lonrho Ltd v Shell Petroleum Co Ltd [1980] 1 W.L.R 627; Re Horsley & Weight Ltd [1982] 3 All E.R. 1045; Winkworth v Edward Baron Development Ltd [1986] 1 W.L.R 1512; Brady v Brady (1988) 3 B.C.C. 535; Liquidator of West Mercia Safetywear v Dodd (1988) 4 B.C.C 30; Facia Footwear Ltd (in administration) v Hinchliffe [1998] 1 B.C.L.C 218; Re Pantone 485 Ltd [2002] 1 B.C.L.C 266; Colin Gwyer & Associates Ltd v London Wharf (Limehouse) Ltd [2002] EWHC 2748 (Ch); [2003] 2 B.C.L.C 153; MDA Investment Management Ltd [2003] EWHC 2277 (Ch); [2005] B.C.C 783; Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nzir [2015] UKSC 23; [2015] 2 W.L.R. 1168, at [123]–[126].

Providing that the duty to promote the success of the company ‘has effect subject to any enactment or rule of law requiring directors, in certain circumstances, to consider or act in the interests of creditors of the company’.

Insolvency Act 1986 s. 214(2) and (3).

Insolvency Act 1986 s. 214(4).

Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986, s. 6(4).

Re Sherborne Associates Ltd [1995] B.C.C 40, at [54].

Re Regentcrest plc v Cohen [2001] 2 B.C.L.C 80, at [120].

The cases have variously described the duty as arising when the company is of ‘doubtful solvency’ (Re Horsely & Weight Ltd [1982] 3 All E.R. 1045, at [442]; Brady v Brady (1987) 3 BCC 535 at 552; Colin Gwyer & Associates Ltd v London Wharf (Limehouse) Ltd [2002] EWHC 2748 (Ch); [2003] 2 B.C.L.C 153, at [74]); ‘near-insolvent’ (The Liquidator of Wendy Fair (Heritage) Ltd v Hobday [2006] EWHC 5803, at [66]); ‘on the verge of insolvency’ (Colin Gwyer & Associates Ltd v London Wharf (Limehouse) Ltd [2002] EWHC 2748 (Ch); [2003] 2 B.C.L.C 153, at [74]); ‘bordering on insolvency’ (Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir [2015] UKSC 23; [2015] 2 W.L.R. 1168, at [123]); in a ‘very dangerous financial position’ or ‘parlous financial state’ (Facia Footwear (in administration) v Hinchcliffe [1998] 1 B.C.L.C 218); or in a ‘precarious’ financial position (Re MDA Investment Management Ltd [2003] EWHC 2277 (Ch); [2005] B.C.C 783, at [75]).

It appears that when the company is insolvent, the creditors’ interests override the interests of the shareholders, and even before the onset of insolvency, English law mandates a strong shift towards creditor interests. In Re MDA Investment Management Ltd [2003] EWHC 2277 (Ch); [2005] B.C.C 783, at [70], Mr Justice Park indicated that when a company is in financial difficulties, although not insolvent, ‘the duties which the directors owe to the company are extended so as to encompass the interests of the company’s creditors as a whole, as well as those of the shareholders’. Mr Justice Lewison took a similar approach in Ultraframe (UK) Ltd v Fielding [2005] EWHC 1638 (Ch), at [1304]. In Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir [2015] UKSC 23; [2015] 2 W.L.R. 1168, Lord Toulson and Lord Hodge rather ambiguously stated that when the company is insolvent or bordering on insolvency, the directors must have ‘proper regard’ for the interests of the company’s creditors, and, later, that the interests of the company ‘are not to be treated as synonymous with those of the shareholders but rather embracing those of the creditors’. But other cases have indicated that creditors’ interests are ‘paramount’, and not only when a company is insolvent but also when it is doubtfully solvent (Colin Gwyer & Associates Ltd v London Wharf (Limehouse) Ltd [2002] EWHC 2748 (Ch); [2003] 2 B.C.L.C 153, at [74]; Roberts v Frohlich [2011] EWHC (Ch) 257; [2012] BCC 407, at [85] and [94]; GHLM Trading Ltd v Maroo [2012] EWHC 61, at [165]; Re HLC Environmental Projects Ltd [2013] EWHC 2876, at [92]), and at least one leading English Queen’s Counsel has suggested that this best summarises the current position in English law (Arnold (2015), at p. 51).

For a more detailed review of the enforcement challenges, see, e.g., Keay (2005a).

Williams (2015).

Company Directors’ Disqualification Act 1986, s. 7.

Finch (1992), at p. 194.

Finch (1990), at pp. 385–389.

Finch (1992), at p. 195 (discussing the role of the DTI; but the same criticisms have been made of the Insolvency Service, the executive branch of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, currently responsible for disqualification).

Including Deregulation Act, Schedule 6, Part 4, which provides the Secretary of State and the Official Receiver with the right to obtain information on director conduct from third parties, the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, s.106, inserting new factors to be considered in every disqualification case, and the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015, s.110, entitling the Secretary of State to apply to court for a compensation order or to obtain a compensation undertaking from a disqualified director.

Hicks (2001), at p. 442.

Jensen and Meckling (1976), at pp. 337–339.

Gullifer and Payne (2015), at p. 768.

Kaplan and Strömberg (2009), at p. 132.

Bratton (2008), at p. 511.

Armour et al. (2002), at pp. 1772–1773.

McKnight (2008), at pp. 149–151.

Segal (1992), Ch. 8.

Armour and Frisby (2001), at p. 93.

Stein (1985), at p. 380.

McKnight (2008), at pp. 882–884.

Takacs (2010), at pp. 5–6.

Paterson (2014), at pp. 337–338.

Harner (2006), at pp. 70–119.

Ibid., at pp. 103–104.

Howard and Hedger (2014), at p. 298, para. 6.20.

Takacs (2010), at p. 24.

Clark (1981), at p. 1252.

Paterson (2014), at p. 353.

Howard and Hedger (2014), at pp. 276–277, paras. 5116–5119.

Cornelli and Karakaş (2012), at p. 12.

Kaplan and Strömberg (2009), at p. 32.

Cornelli and Karakaş (2012), at p. 20.

Ibid., at p. 3.

Ibid., at p. 3.

Kaplan and Stein (1993), at p. 347.

Ibid., at p. 13.

Stapledon (1996), at pp. 125–126.

Insolvency Act 1986, s 214(7).

Stapledon (1996), at p. 127 (discussing other types of intervention, but making the same point about risk and reward).

Easterbrook and Fischel (1996), at p. 10.

Howard and Hedger (2014), at p. 56, para. 2.106, p. 347, para. 6.212, and pp. 354–356, para. 6.237.

Re Pantone 485 Ltd [2002] 1 BCLC 266.

Takacs (2010), at p. 15.

Asimacopoulos and Bickle (2013).

This is because, whilst the transaction is substantively an insolvency, functionally it produces a debt-for-equity swap in which some lenders emerge holding equity in a new holding company for the business.

Spanier (2013).

Re Bluebrook Ltd [2010] B.C.C 209.

Ibid., at [63].

Baird (2006), at p. 1235.

Re Bluebrook Ltd [2010] B.C.C 209, at [59].

Ibid., at [61].

Keay (2008), at p. 691.

Re Bluebrook Ltd [2009] EWHC 2114 (Ch); [2010] B.C.C. 209, at [56].

Ibid., at [49].

Jensen (Jensen 2010), at p. 17.

Ibid., at [54]–[55].

Unocal Copr. v Mesa Petroleum Co 493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985); Revlon Inc v MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings Inc. 506 A.2d 173 (Del. 1986), discussed in Bainbridge (2013).

Belcredi and Ferrarini (2013), at p. 17.

References

ABI Commission to Study the Reform of Chapter 11 (2014) Final Report

Armour J, Frisby S (2001) Rethinking receivership. Oxford J Legal Stud 21:73

Armour J, Cheffins BR, Skeel DA Jr (2002) Corporate ownership structure and the evolution of bankruptcy law: lessons from the United Kingdom. Vanderbilt Law Rev 55:1699

Armour J, Hansmann H, Kraakman R (2009a) Agency problems and legal strategies. In: Kraakman R, Armour J, Davies, P, Enriques L, Hansmann H, Hertzig G, Hopt K, Kanda H, Rock E. The anatomy of corporate law: a comparative and functional approach, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Armour J, Hertig G, Kanda H (2009b) Transactions with creditors. In: Kraakman R, Armour J, Davies, P, Enriques L, Hansmann H, Hertzig G, Hopt K, Kanda H, Rock E. The anatomy of corporate law: a comparative and functional approach, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Arnold M (2015) Directors duties in the zone of insolvency: recent developments. South Square Digest, February, p 46. Available at http://www.southsquare.com/files/SSD%2026elec_Layout%201.pdf. Accessed 9 Oct 2015

Asimacopoulos K, Bickle J (eds) (2013) European debt restructuring handbook. Globe Law and Business, London

Bainbridge SM (2013) The geography of Revlon-land. Fordham Law Rev 81:3277

Baird DG (2006) Private debt and the missing lever of corporate governance. Univ Pennsylvania Law Rev 154:1209

Bebchuk LA, Fried J (2004) Pay without performance: the unfulfilled promise of executive compensation. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bebchuk LA, Fried J, Walker D (2002) Managerial power and rent extraction in the design of executive compensation. Univ Chicago Law Rev 69:751

Belcredi M, Ferrarini G (2013) Boards, incentive pay, shareholder activism. In: Ferrarini G, Belcredi M, Emittenti Titoli SpA (sponsoring body) (eds) Boards and shareholders in European listed companies. Cambridge University Press, UK

Berle A, Means G (1932) The modern corporation and private property. Macmillan, New York

Bozzi S, Barontini R, Ferrarini G, Ungureanu MC (2013) Directors’ remuneration before and after the crisis: measuring the impact of reforms in Europe. In: Ferrarini G, Belcredi M, Emittenti Titoli SpA (sponsoring body) (eds) Boards and shareholders in European listed companies. Cambridge University Press, UK

Bratton W (2008) Private equity’s three lessons for agency theory. Eur Bus Organ Law Rev 9:509

Buchanan J, Tullock G, Rowley CK (2004) The calculus of consent: logical foundations of constitutional democracy. University of Michigan Press, Indianapolis. Ind., Ann Arbor

Cheffins BR, Armour J (2007) The eclipse of private equity. Working Paper No. 339, ESRC Centre for Business Research

Clark RC (1981) The interdisciplinary study of legal evolution. Yale Law J 90:1238

Cornelli F, Karakaş O (2012) Corporate governance of LBOs: the role of boards. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1875649. Accessed 9 October 2015

Easterbrook FH, Fischel DR (1996) The economic structure of corporate law, paperback edn. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Enriques L, Hansmann H, Kraakman R (2009) The basic governance structure: the interests of shareholders as a class. In: Kraakman R, Armour J, Davies, P, Enriques L, Hansmann H, Hertzig G, Hopt K, Kanda H, Rock E. The anatomy of corporate law: a comparative and functional approach, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Finch V (1990) Disqualification: a plea for competence. Modern Law Rev 53:385

Finch V (1992) Company directors: who cares about skill and care? Modern Law Rev 55:179

Gilson RJ, Whitehead CK (2008) Deconstructing equity: public ownership, agency costs, and complete capital markets. Columbia Law Rev 108:231

Gullifer L, Payne J (2015) Corporate finance law: principles and policy. Hart Publishing, Oxford and Portland, Oregon

Hansmann H, Kraakman R, Enriques L (2009) The basic governance structure: the interests of shareholders as a class. In: Kraakman R, Armour J, Davies, P, Enriques L, Hansmann H, Hertzig G, Hopt K, Kanda H, Rock E. The anatomy of corporate law: a comparative and functional approach, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Harner MM (2006) Trends in distressed debt investing: an empirical study of investors’ objectives. Am Bankruptcy Inst Law Rev 16:69

Hicks A (2001) Director disqualification: can it deliver? Journal of Business Law p 433

Howard C, Hedger B (2014) Restructuring law and practice. LexisNexis, London

Jensen MC (1989) The eclipse of the public corporation. Harvard Bus Rev 67:61

Jensen MC (2010) Value maximisation, stakeholder theory and the corporate objective function. J Appl Corp Finance 22:32

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3:305

Kaplan SN, Stein JC (1993) The evolution of buyout pricing and financial structure in the 1980s. Q J Econ 108:313

Kaplan SN, Strömberg P (2009) Leveraged buyouts and private equity. J Econ Perspect 23:121

Keay A (2003) Directors’ duties to creditors: contractarian concerns relating to efficiency and over-protection of creditors. Modern Law Rev 66:665

Keay A (2005a) Wrongful trading and the liability of company directors: a theoretical perspective. Legal Stud 25:431

Keay A (2005b) Formulating a framework for directors duties to creditors: an entity maximisation approach. Camb Law J 64:614

Keay A (2008) Ascertaining the corporate objective: an entity maximisation and sustainability model. Modern Law Rev 71:663

McKnight A (2008) The law of international finance. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Molho I (1997) The economics of information: lying and cheating in markets and organizations. Wiley, UK

Office for National Statistics (2012) Statistical Bulletin. Ownership of UK quoted shares

Olson M (1971) The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Paterson S (2014) Bargaining in financial restructuring: market norms, legal rights and regulatory standards. J Corp Law Stud 14:333