Abstract

Investment funds that claim to focus on socially responsible stocks have proliferated in recent times. In this paper, we verify whether ESG mutual funds actually invest in firms that have stakeholder-friendly track records. Using a comprehensive sample of self-labelled ESG mutual funds (as identified by Morningstar) in the United States from 2010 to 2018, we find that these funds hold portfolio firms with worse track records for compliance with labor and environmental laws, relative to portfolio firms held by non-ESG funds managed by the same financial institutions in the same years. Relative to other funds offered by the same asset managers in the same years, ESG funds hold stocks that are more likely to voluntarily disclose carbon emissions performance but also stocks with higher carbon emissions per unit of revenue. Despite these findings, ESG funds hold portfolio firms with higher average ESG scores. We show that ESG scores are correlated with the quantity of voluntary ESG-related disclosures but not with firms’ compliance records or actual levels of carbon emissions. Finally, ESG funds appear to underperform financially relative to other funds within the same asset manager and year, and to charge higher fees. Our findings suggest that socially responsible funds do not appear to follow through on proclamations of concerns for stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In March 2021, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) created the Climate and ESG Task Force to proactively identify misconduct related to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues.Footnote 1 The taskforce was created in response to a recent explosion of interest in incorporating ESG factors into investment decisions. The asset management industry has responded to the demand for ESG investing by launching numerous “socially responsible” funds that nominally account for factors considered important to a firm’s overall sustainability: the environment (e.g., carbon emissions), social issues (e.g., employee treatment), and governance (e.g., executive compensation). According to the U.S. Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investing, more than $12 trillion of assets under management (AUM) is explicitly linked to ESG issues. The availability of ESG funds is growing rapidly; Morningstar documents a nearly 50% increase in the number of ESG funds available in the United States from 2019 to 2020 alone.

However, the creation of the SEC’s new taskforce represents regulatory concern that ESG funds are not providing asset owners with products that actually reflect concern for stakeholder welfare. In April 2021, the SEC stated that it had identified several asset managers that were misleading investors by marketing funds as ESG-friendly but not making investment decisions consistent with such marketing or,Footnote 2 in some cases, even having a mechanism to “reasonably track” or screen portfolio firms’ ESG performance.Footnote 3 This concern is shared by many members of the asset management industry. For example, in a recent op-ed, BlackRock’s former Chief Investment Officer for Sustainable Investing, Tariq Fancy, states,Footnote 4 “Our messaging helped mainstream the concept that pursuing social good was also good for the bottom line. Sadly, that’s all it is, a hopeful idea. In truth, sustainable investing boils down to little more than marketing hype, PR spin and disingenuous promises from the investment community.”

In this paper, we therefore attempt to verify whether ESG-oriented funds’ claims of picking portfolio firms that exhibit superior treatment of all stakeholders (as opposed to shareholder primacy) are borne out by the evidence. Our empirical approach focuses on whether self-labeled ESG-oriented mutual funds, as identified by Morningstar, invest in firms that have better track records with consumers, employees, the environment, taxpayers, and shareholders. We assess firms’ track records with respect to these groups of stakeholders based on fundamental measures of their behavior – or misbehavior – toward each group. Our primary measure of stakeholder-centric behavior is portfolio firms’ compliance with social (e.g., labor or consumer protection) and environmental laws. We also consider several other measures of stakeholder-centric behavior: carbon emissions, CEO compensation, board composition, and managerial entrenchment.

To ensure that our results are not driven by heterogeneity in asset managers, we limit our main analyses to funds issued by financial institutions that also issued at least one non-ESG fund in the same year; i.e., we compare ESG funds to non-ESG funds managed by the same financial institutions in the same year.Footnote 5 We begin with a comprehensive list, published by Morningstar, of mutual funds based in the United States that self-identify as ESG-oriented. We emphasize that although the list is compiled by Morningstar, it does not reflect Morningstar’s determination of which funds qualify as ESG-oriented. Rather, Morningstar is simply providing an aggregated list of self-identified ESG funds, primarily based on those funds’ prospectuses, fund reports, and websites. While there is substantial heterogeneity in how individual ESG funds claim to select stocks, our reading of several ESG funds’ prospectuses, summarized in Appendix A, suggests that the funds’ stock selection process can roughly be characterized as drawing on both ESG factors and valuation attributes (e.g., value or momentum). However, the funds largely characterize these two sets of criteria as distinct rather than interrelated, in many cases even cautioning that financial performance may suffer as a result of incorporating ESG factors into the investment process. After applying screens for data availability, we identify 147 distinct mutual funds, issued by 74 distinct asset managers, over the period 2010–2018 that claim to be ESG-oriented. We track the stakeholder-related behavior of stocks included in and added to these funds, relative to stocks held by 2428 non-ESG funds run by the same financial institution-years.

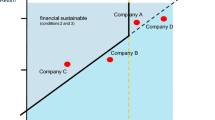

We find no evidence that ESG funds’ portfolio firms outperform non-ESG funds’ portfolio firms with respect to most of the measures of stakeholder-centric behavior that we consider in this paper. In fact, we find that ESG funds’ portfolio firms have significantly more violations of labor and environmental laws and pay more in fines for these violations, relative to non-ESG funds issued by the same financial institutions in the same year. Moreover, we find that ESG funds’ portfolio firms, on average, exhibit worse performance with respect to carbon emissions, in terms of both raw emissions output and emissions intensity (i.e., CO2 emissions per unit of revenue). These results undermine such funds’ claims that they are picking socially responsible stocks for inclusion and suggest substantial greenwashing on the part of ESG funds.

Because carbon emissions disclosure is not mandatory, we also investigate voluntary emissions disclosure.Footnote 6 We find that ESG funds are more likely to pick stocks that voluntarily disclose emissions. Given our other results, these tests suggest that ESG funds may be concerned about the existence of firms’ disclosures rather than the content of the information being disclosed. This finding is consistent with recent work (Drempetic et al. 2017; Lopez-de-Silanes et al. 2019) suggesting that firms’ ESG scores are influenced more by the existence of voluntary disclosures than by the information content of these disclosures.

Our results suggest that ESG funds may rely on ESG scores rather than performing their own due diligence about firms’ environmental and social practices. This conjectured practice, in turn, may lead to investments in firms with poorer levels of stakeholder treatment relative to firms that do not actively incorporate ESG into investment decisions. We provide support for this argument by assessing ESG scores directly. While we do find that ESG funds’ portfolios contain firms with higher average ESG scores, we also find, consistent with Drempetic et al. (2017) and Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2019), that these scores are only correlated with metrics that capture news coverage and the existence and quantity of voluntary disclosure (both with respect to emissions and more generally), but not with the actual content of such disclosures.

Given the findings documented above, we turn to fund managers’ potential motivations for offering ESG products. We find that ESG funds (i) obtain lower stock returns but (ii) charge higher management fees. Moreover, while it is plausible that ESG funds invest in companies with the goal of improving how these companies treat their stakeholders, we test and find no empirical support for this conjecture. Our results raise questions about what purchasers of shares in self-labelled ESG or “socially responsible” mutual funds get in exchange for this higher management fee. We view this as a particularly salient concern, given that in recent years it has become easier for investors to identify and purchase what they believe to be ESG-oriented investment products, which, in turn, has led to a significant increase in inflows to such funds (Hartzmark and Sussman 2019).

Another potential explanation for our findings thus far is that ESG funds may primarily focus on the “G” in ESG (i.e., corporate governance). We find mixed results in this respect. Relative to non-ESG funds, ESG funds’ portfolio firms have lower excess CEO compensation but also lower levels of board independence. The governance characteristics described are typical of high-technology firms, which often have powerful founder-CEOs and boards of directors with limited oversight and influence over top executives. This characterization is consistent with our finding that ESG-oriented funds contain 27% more technology stocks than non-ESG funds issued by the same financial institutions in the same year.

A key takeaway of our study is that asset managers do not necessarily “walk the talk” in following through on claims of picking stocks that engage in stakeholder-friendly behavior. In light of the recent explosion of interest in ESG investing, our study is timely because prior empirical research that examines whether ESG funds actually deliver on their promises to focus on stakeholder-oriented stocks is sparse. Our study complements contemporaneous working papers in another setting by Gibson et al. (2021), Liang, Sun, and Teo (2022), and Kim and Yoon (2021). These studies consider the ESG performance of asset managers that sign the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), pre and post signing. Gibson et al. (2021) find that international US-domiciled institutions that publicly commit to responsible investing by signing the PRI are less likely to pick firms with better environmental, social, and governance (ESG) scores. Liang, Sun and Teo (2022) find that hedge funds that sign the PRI but have lower weighted-average ESG scores also underperform financially. Finally, Kim and Yoon (2021) find that PRI signatories do not improve fund-level weighted average ESG scores, and exhibit a decrease in returns earned, after signing the PRI. Our results are consistent with these studies.

However, our study exhibits two key differences from theirs. First, we consider individual mutual funds, holding constant any differences across asset managers. In contrast, both Gibson et al. (2021) and Kim and Yoon (2021) consider behavior at the asset manager level. Second, and most important, we focus on fundamental measures of stakeholder treatment – based on firms’ misconduct against consumers, employees, and the environment as well as carbon emissions and key aspects of firms’ governance – rather than on commercial ESG scores (as the studies above do). This distinction is important because, unlike Gibson et al. (2021) and Kim and Yoon (2021), we do find a positive correlation between the ESG fund label and ESG scores. We provide evidence that these constructs – commercial ESG scores and fundamental track records toward stakeholders – do not correlate well. We show that this is because commercial ESG scores appear to be driven by news coverage of ESG (consistent with Yang 2021) as well as the existence of firms’ voluntary disclosures about ESG information. ESG scores, however, do not correlate with the actual contents of these voluntary disclosures, consistent with Drempetic et al. (2017) and Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2019). In considering direct measures of stakeholder treatment rather than commercial ESG scores, our paper is also timely and relevant for the SEC’s new Climate and ESG Task Force. While ESG-oriented investors have long relied on commercial scores to reduce information acquisition costs, the SEC, in its April 2021 ESG Risk Alert bulletin, specifically highlighted overreliance on composite ESG scores as a sign of inadequate due diligence and of poor fund-level compliance more generally. The SEC’s bulletin emphasized the need to understand whether ESG funds that claim to incorporate specific environmental or social factors into portfolio allocation decisions actually pick stocks that obtain superior performance with respect to these stated factors.Footnote 7

A skeptic may argue that the goal of many ESG funds is simply to pick stocks that manage ESG risks in a way that maximizes firm value (i.e., financial materiality and not environmental and social materiality).Footnote 8 That is, do fund managers claim to focus on socially responsible stocks, as we implicitly assume, or do they instead claim to focus on stocks that effectively manage the financial impacts of ESG risks? For instance, if BlackRock offers an ESG fund based on MSCI’s ESG indices and claims that the fund selects stocks that are resilient to ESG risks, is this equivalent to claiming that the fund is picking socially responsible stocks?

We acknowledge this alternative explanation with three counterpoints. First, in section 3.1, we provide a detailed discussion of how Morningstar compiles its list of sustainable funds and hence our sample. Notably, Morningstar states that it includes funds whose prospectuses explicitly allude to ESG considerations as a direct reason for investing in specific companies but excludes funds that simply incorporate ESG factors in a “more limited way.” Second, we selected the top 25 funds, sorted by assets under management, in our sample – reflecting 97% of total AUM for the last year of our sample – and read the prospectuses associated with those funds. In 22 out of 25 cases tabulated in Appendix A, we found language suggesting that the funds explicitly consider ESG-related issues as reasons to invest in, avoid, or divest from individual stocks, without citing the potential financial consequences of those firms’ ESG issues as a reason for picking or avoiding them. Collectively, this suggests to us that many – if not all – ESG fund managers do explicitly claim to focus on social responsibility for reasons other than financial materiality. Third, because of disclosure and data limitations, linking ESG factors to explicit financial consequences is non-trivially difficult in practice (Rajgopal 2022). It is therefore not obvious what precise analyses ESG funds conduct to identify value-enhancing strategies vis-à-vis ESG risks. Nonetheless, we agree that this may not be how all fund managers behave. We thus acknowledge the alternative hypothesis that some ESG funds in our sample do not explicitly attempt to pick socially responsible funds and that this may partially explain the results we document.

2 Background

In this section, we summarize prior work related to our paper and outline how we measure whether ESG funds follow through on their promises of social responsibility.

2.1 Prior work on socially responsible mutual funds

Empirical work on the performance of socially responsible mutual funds with respect to their stated goals is sparse. Ramchander et al. (2012) document that announcements of additions (deletions) to the Domini Social 400 (DS400) index, a prominent stock market social responsibility benchmark, are associated with positive (negative) stock prices of such firms. Whether socially responsible funds earn abnormal returns is unclear. Sauer (1997) and Statman (2000) find no significant difference between the financial performance of the Domini Social Index (a socially responsible index or screened version of the conventional S&P 500) and the S&P 500. Statman (2006) reaches the same conclusion when the sample is extended to four popular SRI indices (Domini Social Index, Calvert’s Social Index, Citizen’s Index, and Dow Jones Sustainability US Index) and a longer time period.

More recent work has begun to examine the causes and consequences of investors’ demand for socially responsible investment products. Barber et al. (2021) and Riedl and Smeets (2017) find, using the settings of impact investing and investor surveys, that demand for socially responsible funds may arise for prosocial rather than purely financial reasons. Hartzmark and Sussman (2019) find that, in response to the demand for socially responsible investment opportunities, salient information about a mutual fund’s “sustainability” rating leads to significant net fund inflows. Pastor et al. (2021) analytically model the empirical findings in these three papers, arguing that sustainable investing can arise as equilibrium behavior both for prosocial reasons and as a means of hedging future risk. Consistent with the latter notion, a recent working paper by Chava et al. (2021) finds a relation between lower downside risk and higher ESG ratings, but no association between ESG ratings and unconditional market risk or stock returns more generally.

An implicit assumption of the papers above is that investment products labelled as “socially responsible” do, in fact, make socially responsible investments. However, the demand for socially responsible investment products may lead to greenwashing by asset managers. Three concurrent studies, all using the context of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI), are relevant in this regard. Gibson et al. (2021) construct a firm’s ESG footprint based on a composite of ESG scores provided by three vendors (MSCI, Asset4, and Sustainalytics). They find that this ESG footprint is higher for PRI signatories in Europe relative to those in the US. Kim and Yoon (2021) find that a composite ESG score obtained from three vendors (TruValue Labs, MSCI, and Sustainalytics) does not improve for firms in the funds that sign the PRI. The inflow of investment dollars to the PRI signatories increases by 4.3%, but the returns reported by the signatory funds fall, suggesting that the funds signed the PRI purely for greenwashing or marketing purposes. Consistent with this argument, Liang, Sun, and Teo (2022) document that a significant proportion of hedge funds that signed the PRI have both below-market stock return performance and low ESG ratings. In one sense, our findings complement these papers by documenting that firms held by self-proclaimed ESG funds, as identified by Morningstar, do not have better ESG records, relative to a control sample of non-ESG funds in the same fund family. Our study differs from Gibson et al. (2021) and Kim and Yoon (2021) along two dimensions. First, our unit of analysis is at the fund rather than the asset manager level, representing a distinct stage of individuals’ or entities’ asset allocation decisions. Second, our measurement of firms’ track records toward stakeholders does not rely on vendor-supplied ESG scores, a point we turn to next.

2.2 Assessing whether ESG funds walk the talk

Our objective is partly to confront ESG funds with their advertised missions of social responsibility. However, an objective assessment of whether the firms underlying these funds are indeed socially responsible is difficult. Prior work that investigates this question relies on a label of social responsibility assigned by an external and potentially credible party (e.g., the Domini Social Index, signing on to PRI principles, or ESG scores supplied by vendors). These papers implicitly assume that labels or third-party certifications of social responsibility faithfully measure the environmental, social, and/or governance orientation of a firm. An emerging literature focuses on validating these ratings. One prominent working paper (Berg et al. 2022) documents a low correlation between ESG scores awarded by different ratings vendors to the same firms, while another (Serafeim and Yoon 2021) highlights that ESG rating disagreement dampens the link between ESG news and stock prices. Recent work also shows that these ratings (i) behave as if they add stocks that receive positive media mentions but do not respond to measures of underlying stakeholder treatment (Yang 2021), and (ii) are primarily correlated with the quantity of disclosure – and, hence, mechanically with firm size – but not with the content of information being disclosed (Drempetic et al. 2017; Lopez-de-Silanes et al. 2019). Perhaps as a result of these issues, in its April 2021 ESG Risk Alert bulletin the SEC highlighted a need to move beyond ESG scores in order to better understand the extent to which ESG funds deliver on promises of socially responsible investing. In a statement about the ESG Risk Alert, SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce said that “firms claiming to be conducting ESG investing need to explain to investors what they mean by ESG and they need to do what they say they are doing.”Footnote 9

In this paper, we avoid the issues raised by the papers above as well as the SEC’s ESG Risk Alert by directly considering fundamental measures of how firms treat their stakeholders. In doing so, we answer the SEC’s call to move beyond commercial vendor-provided scores as a method of understanding how ESG investment products work in practice. Our tests center on three primary types of stakeholder treatment measures: (i) comprehensive federal enforcement records pertaining to firms’ (mis)treatment of the environment, employees, and consumers; (ii) the extent to which firms are actually green, measured using data on carbon emissions; and (iii) key features of the firms’ corporate governance structure. We also address fund-level issues including management fees and financial performance.

3 Data

3.1 ESG funds

We begin by obtaining information on ESG-focused mutual funds from the February 2020 version of Morningstar’s annual Sustainable Funds U.S. Landscape Report. This report, which is freely downloadable from Morningstar’s website, provides a comprehensive list of ESG funds available to investors in the United States as well as basic descriptive information about these funds. Because the list of funds in this report does not contain fund identifiers, we supplement the report with an Excel spreadsheet version of the ESG fund list that contains fund ticker information, disseminated one month after the report’s publication and meant to accompany the report.Footnote 10 We do note that the spreadsheet version of the fund list contains slightly more ESG funds (311) than the fund list in the report (303). This disparity results in two funds ultimately entering our sample from the spreadsheet that were not originally contained in the 2020 Sustainable Funds Landscape Report.Footnote 11 We match the fund list to CRSP identifiers (“fundno” and “portno”) through manual ticker searches. In doing so, we obtain complete portfolio holdings data for 235 funds from 2010 to the present.

Crucially, the ESG fund list is based on firms’ self-reported ESG status (obtained from information contained in sources such as fund prospectuses and fund websites) rather than Morningstar’s judgment as to whether the fund should qualify as an “ESG” or “socially responsible” mutual fund on the basis of the fund’s holdings. We also note that Morningstar distinguishes “ESG consideration” funds – those that allude to ESG factors in a limited way – from “ESG” funds, which, according to Morningstar, have a “sustainable investing focus as a central feature of their strategy.” ESG consideration funds are not included in the lists provided in the Morningstar report and corresponding spreadsheet, meaning that the funds in our sample were included because their prospectuses and marketing materials explicitly allude to ESG factors as a core part of their investment strategies. To verify this, we took the top 25 ESG funds by assets under management in our final sample (issued by 17 different asset managers) and read their prospectuses.Footnote 12 In most cases, we found language emphasizing the nominal role of ESG factors in these funds’ decision-making processes. For example, the Parnassus Core Equity Fund’s prospectus states that (emphasis ours) “the Fund will sell a security if the Adviser believes a company’s fundamentals will deteriorate, if it believes a company’s stock has little potential for appreciation or if the company no longer meets the Adviser’s ESG criteria.”

Such examples suggest that the funds in our sample do not claim to care about ESG factors simply for potential reasons of financial materiality. Rather, these funds claim to incorporate ESG considerations for their own sake, although there is significant heterogeneity in whether and how they claim to weight ESG considerations relative to financial ones. For instance, many funds apply ESG criteria to all potential stocks considered for inclusion, while others allow for some part of their portfolios to be driven by financial considerations (e.g., the BNY Mellon Sustainable Equity Fund requires 80% of its portfolio to have no major ESG issues).

Descriptive information in the Morningstar report includes the fund’s inception date as well as the date the fund began its ESG focus, if the fund was not originally an ESG fund; assets under management (AUM); whether the fund has a broader ESG focus or a specific theme (“Impact” or “Sustainable Sector”), and the fund manager (BlackRock, Vanguard, etc.). In addition, Morningstar classifies the theme based on the fund’s disclosures but does not attempt to verify whether the fund’s investment decisions warrant its characterization as being Impact or Sustainable Sector.Footnote 13 Of our final sample, 66% of funds are classified as being broadly ESG focused, 23% are Sustainable Sector, and the remaining 11% are Impact. We also observe Morningstar’s classification as to whether the fund qualifies as being “low-carbon,” a distinction that we exploit in supplemental tests outlined later.Footnote 14

We begin our ESG fund sample in 2010 for two reasons. First, ESG investing became significantly more popular after the 2008–09 financial crisis. Hence, most of our funds have an inception date after 2010. Second, CRSP changed the data provider underlying its Portfolio Holdings database in 2010; as a result, many funds (whether ESG or not) only have holdings information available for 2010 onward. Using this procedure, we identify a comprehensive list of portfolio holdings for 147 ESG funds that invest in US equities, spanning 759 fund-years between 2010 and 2018, as well as for 2428 non-ESG funds spanning 11,210 fund-years between 2010 and 2018. We end the sample in 2018 because, as of this writing, data on many of our key measures of stakeholder behavior is only available through 2018.

Our sample of ESG funds drops from 235 to 147 for three main reasons: (i) some of the most recent ESG funds (i.e., those started in 2019 or 2020) do not have CRSP holdings data for our sample period; (ii) some ESG funds do not invest in large US public equities (instead investing in private firms, small-cap public equities for which we do not have data on misconduct or governance, or foreign firms), meaning that we cannot match their portfolio holdings to common firm-level databases such as CRSP; and (iii) we do not observe any non-ESG funds by the same fund managers in the same year for 24 ESG funds, meaning that our fixed effects structure absorbs all variation and causes these 24 funds to drop out of the sample (as we detail later). We provide more details on the construction of our sample in Table 1.Footnote 15

In Table 2, we provide descriptive statistics on both ESG and non-ESG funds offered by the asset managers in our sample. The 147 distinct ESG funds in our sample are issued by 74 distinct asset managers that represent a total of 361 asset manager-year pairs. As such, each asset manager that offers an ESG fund offers an average of 2.1 ESG funds per year. This average is slightly skewed, as 205 of the 361 (56%) asset manager-year pairs in our sample offer only a single ESG fund. Of the remaining asset manager-years, 68 offer two ESG funds while 88 offer three or more. These figures, of course, are with respect to our sample of asset managers offering at least one ESG fund rather than the broader population of asset managers.

3.2 Compliance violations

To test whether ESG funds pick stocks with better corporate conduct, we incorporate data on compliance violations with respect to federal laws. We obtain this data from the Violation Tracker database, compiled by the non-profit organization Good Jobs First. Violation Tracker provides comprehensive coverage of violations of federal laws written by over 50 US federal agencies. The most common type of violation observed in Violation Tracker pertains to workplace safety, in the form of Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) violations. Other common types of violations pertain to labor (for example, violations of minimum wage laws or taking illegal actions to dissuade unionization), the environment, and consumer protection (e.g., product safety or antitrust). These violations occur across a broad cross-section of industries. Relative to the typical focus in accounting and finance work on financial misconduct, a research design-related benefit of our focus on nonfinancial violations is the frequency with which such violations occur. For example, 24% of firm-years in the underlying data commit at least one violation compared to the 1%–3% violation rate typically seen in SEC AAER type studies (e.g., Kedia and Rajgopal 2011). To this end, the nonfinancial violation data pick up much more than just the most egregious misconduct cases and reflect a broad cross-section of firms, although we acknowledge that we may have missed instances of corporate misbehavior we cannot observe.

We measure compliance violations two ways. First, we consider compliance violations irrespective of the penalizing agency. Second, we separately measure compliance violations pertaining to consumers, labor, and the environment, based on the focus of the federal agency issuing the violation. For each of these measures, we construct variables based on indicators for whether a violation occurred (incidence) as well as based on the dollar amounts of penalties (severity). We caveat that this approach may induce some noise, because observations in Violation Tracker (and in the primary sources Violation Tracker draws upon) are provided on the basis of the year in which their associated penalties were assessed. This is less likely to be an issue for labor and environmental violations, which are typically detected while ongoing (rather than ex post) and for which fines are assessed almost immediately. However, our measurement of consumer protection violations – which commonly reflect Department of Justice cases – may be more susceptible to this issue.

We classify violations as pertaining to consumer protection, labor, environment, or “other” based on Good Jobs First’s classification scheme. Specifically, Good Jobs First assigns all violations to one of nine types, primarily based on the federal agency responsible for assessing the violation: competition, consumer protection, employment, environment, financial, government contracting, healthcare, workplace safety, and miscellaneous. We classify “employment” and “workplace safety” violations as pertaining to labor issues; “environment” violations as pertaining to environmental issues; and “competition” and “consumer protection” as pertaining to consumer issues. We classify the remaining types of violations as “other.” Violations pertaining to labor, consumer protection, and the environment comprise the vast majority of observations in Violation Tracker.

The fines assessed for these violations are typically quite small relative to violation severity and, for the firms that we study, immaterial compared to typical measures of financial performance such as earnings or revenues. For example, the median penalty for noncompliance with labor regulations – typically related to workplace safety (assessed by OSHA) or fair labor standards and compliance with wage and hour laws (assessed by WHD) – is less than $20,000. We view this feature as an econometrically beneficial aspect of the compliance data. More specifically, one concern with ESG funds is that the underlying inclusion methodology is primarily focused on financial performance, in which case labelling such funds as ESG-focused amounts to window-dressing. If ESG funds indeed account for compliance violations in their portfolio selection decisions, we would expect such additions to reflect a purer focus on underlying ESG practices rather than exclusively on financial considerations, because the penalties are almost never financially material for the large firms that comprise our sample.Footnote 16

3.3 Emissions

The most common measure of firms’ environmental performance used by the asset management industry is carbon emissions. To test whether ESG funds pick stocks that obtain superior emissions performance relative to stocks picked by non-ESG funds, we obtain carbon emissions data from Trucost. Trucost is a vendor that collects data on carbon emissions from several different sources (e.g., firms’ financial or sustainability reports, the Carbon Disclosure Project, the EPA) and provides estimated emissions figures for many firms that do not disclose emissions. Estimated figures are pervasive in the data, as only 20% of firms in Trucost’s North America database voluntarily disclose emissions data. We obtain data on scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon emissions from Trucost. Scope 1 refers to emissions from directly owned or controlled sources, such as those generated by a manufacturing firm in the process of making physical goods. Scope 2 refers to emissions that are generated from the consumption of energy used in firms’ operations (e.g., the amount of electricity or steam used). Scope 3 refers to indirect emissions both upstream and downstream. Examples of scope 3 emissions include emissions generated by vendors in a firm’s supply chain, those generated by vehicles used in shipping firms’ goods to customers, and even those generated by employees’ business travel.

3.4 Corporate governance

We construct corporate governance proxies following standard measures from prior literature. Our first governance measure is excess CEO compensation, which we construct using compensation data (specifically, TDC1) from Execucomp. As additional measures of corporate governance we consider board independence, using data from BoardEx, as well as the Bebchuk et al. (2009) entrenchment index. To construct the latter, we obtain, from ISS Governance, data on six corporate governance characteristics that are thought to promote entrenchment by limiting shareholders’ power relative to management’s: staggered boards, limits to shareholder bylaw amendments, requiring supermajorities for merger approval and charter amendments, and the existence of poison pills and golden parachutes.

3.5 Control variables

We control for a variety of fund-level factors in our analyses, based on data from CRSP. These include the percentage of funds within a portfolio, weighted by assets under management (AUM), available to retail investors; a fund’s age; total AUM; and annual stock returns and return volatility (where the latter is calculated using monthly returns). We also control for the mutual funds’ industrial composition using data on portfolio firms’ industry classifications. We provide descriptive statistics for all mutual fund-years included in our sample in Table 3.

4 Research design

Our objective in this paper is to focus on funds that claim to select only socially responsible portfolio firms, as these reflect a convenient way for investors to “put their money where their mouth is” with respect to ESG issues. We test whether ESG funds appear to pick stocks that have superior performance related to a number of fundamental measures of stakeholder treatment. In our tests described in this section and tabulated in Sections 5.1 through 5.5, the unit of analysis is the fund level; i.e., we consider the characteristics of ESG funds’ full portfolios and compare them to the full portfolios of non-ESG funds. Our aim in Sections 4 and 5 is to compare stocks held by ESG and non-ESG funds.

We concentrate on compliance violations as a measure of fundamental underlying ESG performance. We expect high-ESG firms to treat their employees and the environment better, which should be reflected in a lower rate of compliance violations. To test whether ESG-oriented mutual funds choose stock portfolios comprised of funds with superior labor and environmental records, we therefore compare the violation records of ESG funds’ portfolio firms to the violation records of non-ESG funds’ portfolio firms. More specifically, for each mutual fund-year, we construct a value-weighted outcome measure as follows:

where vint denotes the total value of fund i’s shareholdings in portfolio stock n in year t, and FirmBehaviornt denotes one of our dependent measures corresponding to firm n in year t (e.g., an indicator variable for the presence of violations or the dollar amount of said violations, proxies for corporate governance). For example, if FirmBehaviornt is an indicator for whether firm n committed a labor violation in year t, and mutual fund i held $10 worth of shares in companies that committed labor violations in year t and $30 worth of shares in companies that did not commit labor violations in year t, BEHAVIORit would equal \( \frac{10}{10+30}=0.25 \). We compute vint based on calendar-year average holdings for each fund i in each stock n. When considering violations, we exclude from both the numerator and denominator of BEHAVIORit any firms that never show up in Good Jobs First’s Violation Tracker or Subsidy Tracker databases (i.e., firms for which we never see a violation or a subsidy). For example, if a fund holds $95 in portfolio firms covered in the Good Jobs First data universe and $5 in portfolio firms not covered in the Good Jobs First data universe, the denominator of BEHAVIORit – that is, \( {\sum}_n^N{v}_{int} \) – would equal $95. We take this step to avoid erroneously labeling a firm as a non-violator when it may simply be the case that Good Jobs First has not provided parent-subsidiary linkages for that firm. Because Violation Tracker and Subsidy Tracker cover nearly all of the Russell 3000 – and more than 90% of US public equities by market capitalization – we do not view this as a significant constraint. For other measures of FirmBehaviornt, we exclude from the numerator and denominator of BEHAVIORit any firms not covered in the relevant databases (e.g., we exclude firms not covered by Trucost from the calculation of \( {\sum}_n^N{v}_{int}{FirmBehavior}_{nt} \) and \( {\sum}_n^N{v}_{int} \) when BEHAVIORit reflects carbon emissions).

Using the measures of BEHAVIORit above, we compare ESG funds to non-ESG funds by estimating the following series of regressions:

where i indexes the CRSP portfolio, j indexes the asset manager (for example, BlackRock or JPMorgan), and t indexes the year. Our research design relies on asset manager-by-year fixed effects ηjt. We employ this fixed effect structure to ensure that our results are not driven by unobservable differences in portfolio selection across asset managers (e.g., the possibility that some asset managers are across-the-board better than others in accounting for how portfolio firms treat stakeholders) or across time (e.g., the possibility that ESG mutual funds, in general, have changed their ESG preferences over time). Moreover, our use of asset manager-by-year fixed effects rather than separate asset manager and year fixed effects ensures that we also account for any changes in investment strategy by asset managers over time.Footnote 17 To enable maximal comparability of ESG funds and non-ESG funds, we also limit the sample to portfolios run by asset managers that also manage at least one ESG fund in the same year.Footnote 18 Our approach of comparing ESG funds to other funds issued by the same asset manager-year combination also allows us to construct a natural benchmark for each of the ESG funds in our sample. More specifically, in labelling certain products as “ESG” funds, the asset manager is signaling that funds with the “ESG” label should place a greater emphasis, vis-à-vis its other fund offerings, on stakeholder-centric issues. We test whether such signaling is reflected in the asset manager’s ESG fund offerings.Footnote 19

We employ several common fund-level control variables in Eq. (1) above. These include the extent to which the fund is available to retail investors; the natural logarithm of the fund’s age, in years; the natural logarithm of the fund’s total net assets (aggregated to the CRSP portfolio level, i.e., across variants of the same portfolio offered as different funds); and the fund’s financial performance and risk, measured as annual returns and annual return volatility, respectively. In addition, although a mutual fund does not have an “industry” in and of itself, it is possible that funds with different industry mixes in their portfolios will display mechanical differences in ESG performance. For example, a fund that focuses on technology stocks is less likely to have a high number of environmental violations by its portfolio firms, while a fund that focuses on oil and gas firms is likely to have more environmental violations. To ensure that our results are picking up more than just differential industry compositions across ESG funds’ and non-ESG funds’ portfolios, we also control for the percentage of the fund’s assets that are invested into (i) technology stocks; (ii) oil, gas, and coal stocks; and (iii) sin stocks. We measure technology stocks following the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ approach, as outlined in Hecker (2005); oil, gas, and coal stocks as being in two-digit SIC codes 12 and 13; and sin stocks following Hong and Kacperczyk (2009).

5 Results

5.1 Compliance violations for poor stakeholder-centric behavior

We begin our analysis of ESG funds in Table 4, where we assess whether ESG funds’ portfolio firms have labor, environmental, and consumer-related practices that are superior to non-ESG funds’ portfolio firms. In columns (1), (3), (5), and (7), the dependent variable is based on firm-year indicators for the incidence of a violation; i.e., the dependent variable reflects a value-weighted average of the number of firms that committed a violation (regardless of the penalty amount associated with the violation). In columns (2), (4), (6), and (8), we instead consider penalty amounts. The dependent variable in these columns is the natural logarithm of the value-weighted average penalties paid for compliance violations by portfolio firms. Columns (1) and (2) focus on all violations; columns (3) and (4) focus on labor violations; columns (5) and (6) focus on environmental violations; and columns (7) and (8) focus on violations of consumer protection laws.

The positive and significant coefficients in column (1) suggest that ESG funds actually perform worse than non-ESG funds offered by the same fund managers with respect to selecting firms with track records of stakeholder-friendly behavior. From columns (3)–(8), it appears that this result is driven by labor and, to a lesser extent, environmental violations. We observe in columns (3) and (4) that ESG funds choose portfolio firms with a higher rate of labor violations, i.e., firms that are more likely to engage in wage theft against vulnerable employees or to endanger employees’ health and safety through violations of OSHA standards. We view this finding as particularly salient in light of recent scandals tying “high-ESG” firms to poor labor practices, most notably the case of Boohoo (a major UK clothing retailer held by most UK-based ESG funds until July 2020, when it came to light that much of Boohoo’s production was done in factories using modern slavery).Footnote 20 Our results suggest that cases such as Boohoo’s may not be an aberration with respect to firms held by ESG funds engaging in stakeholder-unfriendly behavior.

In columns (5) and (6) we find no evidence that ESG funds, on average, hold firms with superior compliance with environmental regulations (e.g., with respect to the Clean Air Act or the Clean Water Act). In column (5) we show that there is no statistically significant difference in the rate of environmental violations by ESG funds’ and non-ESG funds’ portfolio firms, while in column (6) we show that average penalties for environmental violations are actually higher for ESG funds’ portfolio firms. Finally, in columns (7) and (8), we observe some evidence that ESG funds pick stocks with a lower rate of consumer protection violations. This result may be driven by the fact that consumer protection violations in our sample most commonly reflect Department of Justice sanctions, which typically receive a high degree of press coverage and are more likely to be discussed in corporate disclosures such as 8-K and 10-K filings. The disclosure mechanism would complement findings, from prior and concurrent research (Lopez-de-Silanes et al. 2019; Yang 2021), that ESG products react to news coverage and voluntary disclosure rather than to underlying compliance issues directly.

5.2 Carbon emissions

We turn next to carbon emissions, which investors have focused on in recent years as a key measure of firms’ environmental commitments (Garvey et al. 2018). We argue that funds claiming to invest in ESG-oriented firms should emphasize portfolio firms’ carbon emissions performance as perhaps the single most salient measure of the “E” in ESG. We test this assertion by examining whether ESG funds pick stocks with superior carbon emissions performance relative to non-ESG funds.

We focus on three measures that capture slightly different aspects of a firm’s emissions performance. US firms are typically not required to disclose carbon emissions figures; as outlined in Section 3, the majority do not. Our first emissions-performance measure is therefore based on the extent to which portfolio firms voluntarily disclose carbon emissions figures. Such disclosures could plausibly represent a firm’s commitment to accountability with respect to its environmental practices, which ESG funds should view favorably. Our second measure reflects the natural logarithm of raw (i.e., unscaled by firm size) carbon emissions figures, in metric tons of CO2. While we caution that this measure is highly correlated with measures of firm size (Aswani et al. 2022), total emissions is nonetheless a metric that regulators frequently focus on in the context of cap-and-trade schemes and has been studied extensively in prior academic work (e.g., Bolton and Kacperczyk 2021). ESG funds may therefore focus on firms with lower absolute emissions, as such firms may be less likely to invite scrutiny for their emissions practices. Finally, we consider carbon emissions intensity, a commonly used metric in industry, which is defined as the ratio of emissions to total revenues (Garvey et al. 2018; Bolton and Kacperczyk 2021). This measure captures the relative carbon efficiency or “greenness” of a firm’s production process. We argue that firms with more environmentally friendly production practices should have lower emissions intensity. We construct each of these three measures for scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

We find in Table 5 that ESG funds are more likely to hold firms that voluntarily disclose emissions. However, we also observe that ESG funds do no better in selecting portfolio firms based on their actual emissions performance: we observe no difference in scope 1 emissions (whether based on raw emissions or emissions intensity) between ESG funds’ and non-ESG funds’ portfolio firms, and find that ESG funds select portfolio firms with higher levels of scope 2 and 3 emissions, i.e., firms with a greater indirect carbon footprint. Collectively, the results in Tables 4 and 5 seem inconsistent with the stated goals of ESG funds.

5.3 Corporate governance

One possible explanation for our findings above is that ESG funds may primarily be focused on the “G” (governance) in ESG rather than the “E” or “S” (environmental or social). If this is the case, ESG funds should invest in stocks that score higher on standard proxies for corporate governance relative to the stocks that non-ESG funds invest in. We directly test this possibility in Table 6 using three common proxies for corporate governance: abnormal CEO compensation, board independence, and the Bebchuk et al. (2009) entrenchment index.

Our results related to corporate governance are mixed. While we find in Column (1) that ESG funds’ portfolio firms pay their CEOs lower levels of excess compensation than non-ESG funds, we also find, in Column (3), that ESG funds hold portfolio firms with lower levels of board independence relative to non-ESG funds. These results are consistent with ESG funds placing greater weight on high-technology stocks, which frequently have CEOs with relatively low direct compensation but high equity holdings and enormous amounts of power (e.g., through dual-class shares) as well as boards with limited director independence. Consistent with this observation, we observe, in an untabulated analysis, that ESG funds’ portfolios hold 27% more technology stocks on average than non-ESG funds.Footnote 21

5.4 Is the effect of stakeholder-centric behavior picked up by ESG scores?

Our results thus far do not support the notion that ESG funds choose stocks with superior treatment of stakeholders. However, one explanation for our findings is that ESG funds often base their portfolio allocation decisions on proprietary ESG ratings supplied by information intermediaries such as MSCI and Thomson Reuters. A commonly given reason for ESG investment products’ reliance on ESG scores is that information acquisition for a large number of firms is expensive and time-consuming; in the face of limited resources, an asset manager may view ESG scores as a reasonable source of information that, while imperfect, is better than nothing. In this section, we directly test the possibility that proprietary ratings drive fund inclusion decisions using two common sets of proprietary ESG ratings (MSCI’s KLD and Thomson Reuters’ Asset4).Footnote 22

We present analyses using ESG scores in Table 7. In Panel A we document that ESG funds select stocks with higher ESG scores, using both KLD and Asset4 ratings. This result differs from Kim and Yoon (2021), who find no difference in asset manager-weighted ESG scores between signers and non-signers of the UN Principles for Responsible Investing, and highlights a critical difference between our study and theirs. Kim and Yoon’s (2021) unit of analysis is the asset manager level; within an asset manager, most individual funds are typically not labeled as being ESG-oriented. In contrast, our unit of analysis is at the fund level. Our results highlight the importance of studying within-asset-manager differences, especially given that asset allocation decisions typically follow a two-step process: individuals or entities (i) first select an asset manager to invest their money with, then (ii) select from a menu of the chosen asset manager’s investment products. We show that ESG scores are correlated with nominal ESG orientation with respect to (ii), while Kim and Yoon (2021) show that ESG scores are not correlated with nominal ESG orientation with respect to (i).

The results in Table 7, Panel A may be surprising given our other findings that ESG funds do not pick stocks with superior stakeholder treatment. In Panel B of Table 7, we explore the reasons for this disparity by studying the determinants of ESG scores. We control for news coverage, given recent work (e.g., Yang 2021) arguing that ESG scores focus on news headlines rather than underlying fundamentals. We obtain data on negative news coverage from RepRisk.Footnote 23 For each negative news article, RepRisk identifies the topic (labor, environment, human rights, or corruption) as well as a ternary measure of “severity” (low, medium, or high) and “reach” (again low, medium, or high).Footnote 24 We retain articles with medium or high severity as well as medium or high reach and construct indicator variables for each topic. We are not able to map individual articles analyzed in RepRisk to specific compliance violations.

In addition to news coverage, recent literature also finds that ESG scores fixate on the existence and quantity of voluntary disclosure about ESG issues rather than the actual contents of disclosures (Lopez-de-Silanes et al. 2019). We thus control for firms’ voluntary disclosure quantity. We do so by using (i) the Bloomberg ESG disclosure score as in Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (2019), as well as indicator variables for whether firms voluntarily disclose (ii) scope 1 emissions and (iii) labor costs. We hasten to clarify that the Bloomberg ESG disclosure score is not an ESG score in the typical sense: it is a measure of the quantity of disclosure but does not attempt to score what has been disclosed (i.e., it does not score a firm’s actual ESG-centric practices in the way that typical ESG scores attempt to).

We present results using KLD scores in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7 Panel B, and results using Asset4 scores in columns (3) and (4). We find that federal violations do not appear to negatively influence either vendor’s ESG scores. This result suggests that ESG scores may be orthogonal to firms’ underlying stakeholder treatment and, in turn, why it is possible for funds to invest in portfolio firms that have both higher ESG scores and a higher violation rate.

In contrast to our violation results, we find evidence of a relation between ESG scores and ESG-related voluntary disclosure. Both KLD and Asset4 scores are higher when firms voluntarily disclose carbon emissions figures (although, curiously, these scores do not appear to correlate with the emissions intensity figures actually being disclosed). We also find a strong correlation between ESG scores and the amount of ESG-related voluntary disclosure that firms provide, given the positive and significant coefficients in all four columns on the Bloomberg ESG disclosure score. In Columns (2) and (4) we additionally control for negative ESG-related .news coverage, using data from RepRisk as outlined above; data limitations mean that the sample in both cases shrinks by nearly two-thirds. Perhaps because of this sample attrition, or because of our firm fixed effects design, we do not find an incremental relation between labor-, environmental-, or human rights-related news and RepRisk bad news coverage (although we do find a link between bad news related to corruption and KLD scores). These results further support our paper’s finding that the metrics used by ESG investors in their portfolio allocation decisions appear to be correlated with measures of the quantity of ESG information available but not with the quality of firms’ underlying stakeholder treatment. This is a particularly significant concern in light of suggestive evidence that firms may attempt to manipulate or greenwash their own ESG scores by providing voluntary disclosures that vendors subsequently rely on.Footnote 25 The firms with the strongest incentives to provide disclosures that lead to higher ESG scores may also be those with worse performance along other dimensions (i.e., firms that have more to hide). Combined with an overreliance on ESG scores by ESG funds, this would explain the divergence between our results in Table 7 pertaining to ESG scores and our results in Tables 4, 5 and 6 pertaining to fundamental measures of stakeholder treatment. That is, ESG funds are likely not explicitly choosing portfolio firms based on those firms having worse compliance records. However, these funds’ reliance on ESG scores – and, in turn, these scores’ dependence on voluntary disclosure but not hard information – may lead to the situation we observe.

5.5 “Sustainable sector” and “low carbon” funds

Our findings thus far suggest that self-labeled ESG-oriented funds do not “walk the talk” with respect to concerns for portfolio firms’ stakeholder treatment. However, in recent years, certain ESG funds have begun to receive varying levels of external certification; it is plausible that funds actively seeking third-party certification of ESG status are more likely to pick stocks that are more stakeholder-centric, relative to non-ESG funds. We test this notion directly by considering the most notable recent third-party certification: Morningstar’s Low Carbon Designation. In addition, Morningstar classifies several ESG funds as “Sustainable Sector” based on their claims to invest in specific environmentally friendly companies and industries. The distinction between Low Carbon funds (reflecting third-party certification) and Sustainable Sector funds (reflecting funds’ or asset managers’ self-classification) allows us to assess whether third-party certification plays a role in ESG funds living up to their promises.

The Low Carbon Designation, introduced in 2018, relies on a proprietary Carbon Risk Score assigned by Sustainalytics. While we cannot back out these risk scores precisely, Sustainalytics claims that the Carbon Risk Score relies on companies’ exposure to fossil fuel companies as well as their scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon emissions. Morningstar computes a weighted average Carbon Risk Score, based on funds’ portfolio holdings, and assigns its Low Carbon Designation to funds with scores in the bottom decile.Footnote 26 We caveat that the Low Carbon Designation only commenced in 2018 and, hence, was primarily applied ex post to the funds we consider in our sample. While the designation was awarded partially based on pre-2018 performance – i.e., performance during our sample period – we are likely introducing some degree of measurement error in labelling funds as “Low Carbon” cross-sectionally without being able to assess whether these funds would have qualified for Morningstar’s Low Carbon designation over the entirety of our sample period.

After identifying Sustainable Sector and Low Carbon designated ESG funds, we re-estimate Eq. (1) two ways. First, we partition the ESG fund indicator into three separate indicators according to the way in which the fund classifies itself: Sustainable Sector, Impact, or ESG Focus. Second, we partition the ESG fund indicator into separate indicators for Low Carbon and non-Low Carbon ESG funds. We present the results using this approach in Table 8. For parsimony, we tabulate results only for the dependent variables that are likely to be the most relevant to a fund’s status as Sustainable Sector or Low Carbon: environmental violations, emissions disclosure, and emissions intensity. For the sake of brevity, we tabulate emissions results using only Scope 1 emissions.

Our results highlight the role that third-party certification of funds may play vis-à-vis funds self-labelling as being ESG-oriented. Specifically, in column (1) we see that Sustainable Sector funds – which should outperform on ESG issues – in fact hold firms with more violations of environmental laws relative to non-ESG funds issued by the same asset manager-by-year. Additionally, while we observe in columns (2) and (3) that other types of ESG funds (ESG Focus and Impact) attain superior emissions performance in the sense that they pick stocks with better disclosure and lower scope 1 emissions intensity, self-labeled Sustainable Sector funds are no different from their peer non-ESG funds (and significantly worse than non-Sustainable Sector ESG funds). These findings are in direct contrast with our results for third party-certified Low Carbon funds in columns (4)–(6). In column (4) of Table 8, we find that neither Low Carbon funds nor non-Low Carbon funds hold portfolio firms with a different rate of environmental violations relative to non-ESG funds. We next turn to emissions disclosure and performance. Unsurprisingly, given that the Low Carbon designation is based on emissions, we observe in columns (5) and (6) that Low Carbon funds are more likely to disclose scope 1 emissions figures and have lower scope 1 emissions intensity, relative to non-ESG funds. Our results imply that Low Carbon funds outperform non-Low Carbon funds and non-ESG funds with respect to emissions performance, suggesting some value to third-party certification (in this case by Morningstar) in impeding firms’ and funds’ potential attempts at greenwashing.

5.6 ESG fund performance and fees

Our findings thus far suggest that ESG funds do not pick portfolio stocks with superior underlying stakeholder treatment. It seems natural to ask whether the fees paid by fund holders for buying the ESG-friendly label from a fund are justified in terms of the ESG and return performance of the fund’s stocks. That is, in agreeing to pay the management fees associated with ESG funds, the purchasers of shares in ESG funds have already agreed to internalize the costs of ESG-related screening. However, it is not clear that such screening results in superior financial or ESG performance for their invested capital. In addition, the popular press and former investment professionals suggest that a potential reason for asset managers to offer ESG funds is the ability to charge higher management fees. For example, in another recent op-ed, BlackRock’s former Chief of Sustainable Investing, Tariq Fancy, stated, “There’s no reason to believe [ESG investing] achieves anything beyond sort of giving [asset managers] more fees.”Footnote 27

Our goal in this section is to test the assertion above. In column (1) of Table 9, we test whether ESG funds obtain superior stock return performance to non-ESG funds. The dependent variable in column (1) is calendar-year buy-and-hold returns. The negative coefficient on the ESG fund indicator in this column suggests that ESG funds underperform non-ESG funds held by the same asset managers in the same years. Despite this underperforming, we find, in column (2), that ESG funds charge higher management fees. Given that ESG funds outperform other stocks neither financially nor with respect to picking firms with superior stakeholder treatment, this result raises the question of what justifies the higher management fees.Footnote 28

In columns (3) and (4) of Table 9, we replicate the approach taken in Section 5.5 and consider Low Carbon and non-Low Carbon funds separately. We do not find any statistically significant differences between Low Carbon funds and non-ESG funds for either stock returns or management fees. However, we find that non-Low Carbon funds underperform financially yet charge higher management fees relative to non-ESG funds. Put another way, the results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9 are driven by non-Low Carbon funds. Many Low Carbon funds use low-cost passive screening methods, simply minimizing exposure to industries such as oil, gas, and coal; the latter sectors have underperformed the market during our sample period. However, our results for non-Low Carbon funds – which are more likely to be actively managed – raise questions as to what exactly an ethically-minded asset owner gets in return for entrusting their capital to an actively-managed ESG fund with higher fees.

6 Additional analyses

6.1 Are there ex post effects of ESG investor presence?

While we find no evidence that ESG funds pick portfolio firms that exhibit superior stakeholder treatment, it is possible that ESG funds focus on monitoring rather than selection. Prior research (e.g., Dimson et al. 2015) as well as prominent organizations such as the UN PRI argue that this is a key role for would-be ESG investors.Footnote 29 If such a monitoring role has an effect, we should observe that portfolio firms’ ESG performance improves as they become more heavily scrutinized by ESG-conscious investors. We test this assertion through a series of analyses at the firm (rather than fund) level, estimating the following regression:

In Eq. (2), FirmBehaviorkt represents firm-level analogues of the dependent variables used in Tables 4, 5 and 6, while ESGPresencekt is the natural logarithm of one plus the number of ESG funds with firm k in their portfolios in year t. We also control for size (measured using market value), market to book ratio, returns, return volatility, return on assets (ROA), and leverage, as well as for firm and year fixed effects (γk and δt). If ESG funds play a role in monitoring portfolio firms’ stakeholder treatment, then we should see β1 > 0. However, our results, which we do not tabulate for brevity, do not support the potential “monitoring” or “voice” story: across all specifications except for emissions disclosure, β1 is statistically insignificant.

6.2 Selection

Our results thus far raise questions about what actually drives portfolio allocation decisions. While we cannot address selection issues at the fund level (as we do not observe any characteristics about ESG funds that reflect information about those specific funds prior to fund inception), we take an alternate, feasible approach by studying behavior at the asset manager level. We model (i) the probability that an asset manager will offer at least one ESG product, and (ii) the number of ESG funds that an asset manager offers. We estimate these quantities as a function of similar variables to those used as controls in Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7, using asset manager-level weighted averages for all quantities other than AUM. In both cases, we measure the dependent variable one year ahead to ensure that our results do not reflect potential reverse causality.

We find that, unsurprisingly, larger asset managers are more likely to offer ESG funds. We also observe that asset managers with a higher percentage of their portfolios invested into stocks that are typically removed through exclusionary screening by ESG funds – sin stocks and oil, gas, and coal stocks – are less likely to offer ESG funds. Conversely, asset managers that hold portfolio firms with better emissions performance – i.e., lower scope 1 emissions intensity – are more likely to offer ESG funds. Interestingly, we observe no correlation between portfolio firm compliance behavior and the likelihood that an asset manager offers an ESG fund.

Perhaps our most interesting result in this section is the robust negative correlation between management fees and the incidence and number of subsequent ESG fund offerings by asset managers. This result is consistent with asset managers using ESG products primarily as a vehicle to command higher management fees, as is often argued by the media, regulators, and even former asset managers themselves.Footnote 30

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we attempt to verify whether the ideals related to environmental, social and governance underlying ESG-oriented investing are actually reflected in the shareholdings of a comprehensive list of ESG-oriented mutual funds. We measure the fundamentals with respect to ESG- and stakeholder-centric performance using several sources of data, including federal violations related to environmental and labor laws, carbon emissions, CEO compensation, managerial entrenchment, and board independence. We find no evidence that ESG funds actually pick stocks with better “E” and “S” relative to non-ESG funds by the same issuers. In fact, on average, ESG funds pick firms with worse employee treatment and environmental practices than non-ESG funds. Despite this track record, we find that ESG funds charge higher management fees and obtain lower stock returns relative to non-ESG funds run by the same asset managers in the same years.

A combined read of the evidence presented in the paper suggests that the correlation between self-proclaimed high-ESG funds and their return and stakeholder-friendliness records is underwhelming. These results raise several questions about whether the declaration of high-minded ideals by ESG funds that charge higher management fees is cheap talk and whether commercially available ESG ratings really capture a firm’s ESG orientation. We caveat that, in light of recent work by Gibson et al. (2021) suggesting that greenwashing is stronger in the United States, the extent to which our results may generalize to other countries is an open question. Nonetheless, in light of a recent explosion in ESG investing by both retail and institutional investors, our work suggests a need for better verification of ESG funds’ claims of picking stakeholder-friendly stocks.

We end with the caveat that some ESG funds in our sample may not explicitly focus on potential portfolio firms’ social responsibility, and that this may partially explain the results we document. However, our review of the prospectuses of the top 25 funds in our sample suggests that fund managers pick stocks using a combination of valuation-based factors and ESG considerations. How much weight is attached in practice by ESG funds to valuation considerations as opposed to ESG factors is a question worthy of future research.

Notes

Our results are robust to relaxing this restriction.

In practice, not all firms that disclose may actually be doing so fully voluntarily; disclosure often comes in response to pressure from third parties such as asset managers. While we are able to observe the existence of emissions disclosure, we are not able to observe the reasons for a firm’s choice to disclose.

MSCI states that one goal of its ESG ratings is to “measure a company’s resilience to long-term, industry material environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks” (https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings).

We obtained the spreadsheet from https://www.morningstar.com/articles/977271/morningstars-quintessential-list-of-sustainable-funds (last accessed April 27, 2022).

These two funds are the Nuveen Winslow Large-Cap Growth ESG I and the Vanguard 500 Index Investor. We suspect that the latter, which is an S&P 500 index fund, was added to the spreadsheet by Morningstar in error. However, to avoid giving the impression that the ultimate list of ESG funds in the sample is driven by the authors’ judgment, we retain this fund in our estimation sample. All of our results hold in robustness tests that drop this fund from our sample.

We provide a list of these 25 funds and their prospectuses in Appendix A.

We obtain information on fund type from the Sustainable Funds Landscape Report. As noted above, two funds (the Nuveen Winslow Large-Cap Growth ESG I and the Vanguard 500 Index Investor) enter our sample via the Morningstar-disseminated spreadsheet that are not listed in the report. To classify these two funds, we used Morningstar’s online ESG Screener tool (https://www.morningstar.com/esg-screener), which allows the user to search for funds according to these classifications. Neither fund appears in the search results for “Impact Fund” or “Environmental Sector Fund” (which corresponds to the Sustainable Sector designation from the report), so we label these two funds under Morningstar’s broader third category used for all other ESG funds, “ESG Focus.” Nonetheless, for robustness, we re-run our analyses that rely on fund type classification without these two funds; our conclusions do not change.

We obtain information on funds’ low carbon designations and ESG focus from the Sustainable Funds Landscape Report. For the two funds that enter our sample from the Morningstar-disseminated spreadsheet that are not listed in the report, we obtain information on these funds’ Low Carbon designations directly from Morningstar’s website.

We note that the 32 funds that were dropped for lack of data on portfolio holdings are smaller, younger, and worse-performing than the 171 funds that we have holdings data on. Specifically, the 32 dropped funds are on average 5.27 years old, have mean log assets under management (AUM) of 3.58, and earn 3.67% in average annual stock returns; by contrast, the 171 funds with holdings data are on average 11.05 years old, have mean log AUM of 4.91, and earn 7.49% in average annual stock returns. We therefore acknowledge that the funds we drop may be systematically different from the ones we keep (e.g., they may primarily invest in private projects); however, because of lack of data on the firms comprising these funds’ portfolio holdings, we cannot empirically test this. Nonetheless, given the relative number of funds dropped versus kept, we do not view this as significant enough sample attrition to fundamentally alter our inferences.

Regulatory constraints (e.g., fine structures codified into law) prevent fines from increasing at the same rate as the economic impact of the violations they are assessed for. For example, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is not allowed by law to assess any punitive damages; it can only collect back pay and lost wages. Similarly, OSHA and the WHD have rigid fine schedules that do not often change. For instance, OSHA’s fine schedule has changed twice in the last 30 years (once in 1990 and then in 2015, as per the Wall Street Journal (https://www.wsj.com/articles/osha-fines-to-rise-for-first-time-since-1990-1446603819)). As an illustration of our point, note that OSHA cannot charge more for a violation if it results in a worker’s death, relative to a similar violation that does not result in fatalities. While a few agencies, like the DOJ, have a lot of flexibility with respect to the size of the penalty, such observations constitute a small percentage of our sample.

For example, BlackRock has been cited extensively by popular press as an asset manager that has increased its overall ESG focus over time (see, e.g., https://www.reit.com/news/videos/blackrock-incorporating-esg-risk-valuation-system). While using separate fund manager and year fixed effects will not account for this shift in strategy over time, our use of fund manager-by-year fixed effects does control for this type of strategic shift.

Relaxing our fixed effects structure by using asset manager and year fixed effects – rather than asset manager-by-year fixed effects – allows us to retain the 24 funds that drop out due to their asset managers not issuing any non-ESG funds. In untabulated analyses, we verify that doing so does not alter our conclusions.

It is possible that funds run by the same asset manager in the same year may not be completely independent in the sense that they rely on centralized research or decision-making processes. In turn, this could lead to ESG funds performing no better than non-ESG funds within an asset manager-year. However, we do not view this as a threat to validity: if managers making portfolio allocation decisions for ESG funds rely on the same underlying processes as for non-ESG funds, then an investor could choose one of the asset manager’s non-ESG products and get the same ESG performance as in the ESG fund for lower fees.

For further information see, e.g., the following FT article about why so many ESG funds held Boohoo prior to its scandal: https://www.ft.com/content/ead7daea-0457-4a0d-9175-93452f0878ec

We provide additional support for this assertion by re-estimating our main tests on an entropy-balanced sample. We balance on all control variables used in our main analyses as well as asset manager and year fixed effects. While the results in Tables 4, 5, and 7 hold, the results in Table 6 (related to governance) disappear after accounting for the difference in technology holdings by ESG and non-ESG funds.

We acknowledge that our approach does not capture ESG scores across all vendors and that scores from different vendors are not perfectly correlated; we make use of the data vendors we have access to. Nonetheless, as KLD and Asset4 were by far the largest vendors – and the most frequently used by investment professionals – during our sample period, we do not view this as a significant limitation. In any case, the limited coverage of other vendors would pose problems for the calculation of our weighted-average fund-level dependent variables.

RepRisk is a data provider specializing in ESG-related risk. One of its key databases compiles a comprehensive list of negative ESG-related news articles for covered firms and classifies various attributes of these articles.

Severity reflects the underlying news itself, while reach reflects the influence of the news source. Hence, reach and severity are not perfectly correlated.

Further details can be found at https://s21.q4cdn.com/198919461/files/doc_news/2018/Morningstar-Low-Carbon-Designation-Methodology-Final.pdf.

An alternative interpretation of the results in Table 9 arises from a recent working paper by Gantchev et al. (2022), who argue that mutual funds’ attempts to improve ESG performance increase demand for “sustainable” stocks, which in turn creates buying pressure and causes high-ESG stocks to be overvalued. If this explains the results in Table 9, one implication of Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7 would be that mutual funds create buying pressure based on ESG scores but, as an unfortunate byproduct, also increase demand for shares of high-violation firms.

See, e.g., https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=4839.

References

Aswani, J., A. Raghunandan, and S. Rajgopal. (2022). Are carbon emissions associated with stock returns? Working paper. Available at https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3800193.

Barber, B., A. Morse, and A. Yasuda. (2021). Impact investing. Journal of Financial Economics 139 (1): 162–185.

Bebchuk, L., A. Cohen, and A. Ferrell. (2009). What matters in corporate governance? Review of Financial Studies 22 (2): 783–827.

Berg, F., J. Koelbel, and R. Rigobon. (2022). Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Review of Finance, forthcoming.

Bolton, P., and M. Kacperczyk. (2021). Do investors care about carbon risk? Journal of Financial Economics 142 (2): 517–549.

Chava, S., J. Kim, and J. Lee. (2021). Risk, return, and environmental and social ratings. Working paper. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3814444

Dimson, E., O. Karakas, and X. Li. (2015). Active ownership. Review of Financial Studies 28 (12): 3225–3268.