Abstract

Background

Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic persons with MS (pwMS) are more likely to experience rapid disease progression and severe disability than non-Hispanic White pwMS; however, it is unknown how the initiation of high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) differs by race/ethnicity. This real-world study describes DMT treatment patterns in newly diagnosed pwMS in the United States (US) overall and by race/ethnicity.

Methods

This retrospective analysis used the US Optum Market Clarity claims/electronic health records database (January 2015–September 2020). pwMS who were first diagnosed in 2016 or later and initiated any DMT in the two years following diagnosis were included. Continuous enrollment in the claims data for ≥ 12 months before and ≥ 24 months after diagnosis was required. Treatment patterns 2 years after diagnosis were analyzed descriptively overall and by race/ethnicity.

Results

The sample included 682 newly diagnosed and treated pwMS (non-Hispanic Black, n = 99; non-Hispanic White, n = 479; Hispanic, n = 35; other/unknown race/ethnicity, n = 69). The mean time from diagnosis to DMT initiation was 4.9 months in all pwMS. Glatiramer acetate and dimethyl fumarate were the most common first-line DMTs in non-Hispanic Black (28% and 20% respectively) and Hispanic pwMS (31%, 29%); however, glatiramer acetate and ocrelizumab were the most common in non-Hispanic White pwMS (33%, 18%). Use of first-line high-efficacy DMTs was limited across all race/ethnicity subgroups (11-29%), but uptake increased in non-Hispanic Black and White pwMS over the study period.

Conclusion

Use of high-efficacy DMTs was low across all race/ethnicity subgroups of newly diagnosed pwMS in the US, including populations at a greater risk of experiencing rapid disease progression and severe disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Prior research has demonstrated the potential long-term benefits of early treatment with high-efficacy DMTs (heDMTs); however, little is known about recent treatment patterns in multiple sclerosis (MS), including the uptake of heDMTs, overall and by race and ethnicity. |

In this real-world study using linked claims data and electronic health records, only 27% of newly diagnosed persons with MS (pwMS) initiated any heDMT as the first-line treatment after MS diagnosis. |

Although prior research has found that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS are more likely to experience rapid disease progression and severe disability, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS included in the study frequently received a low or moderate-efficacy disease modifying therapy as the first-line treatment after diagnosis. |

1 Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory, and degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that can lead to permanent and progressive neurological disability. Nearly one million people in the US are affected by MS, with a total economic burden of $85.4 billion [1, 2].

Early therapeutic intervention with high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies (heDMTs) in persons with relapsing MS has been linked to reductions in new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) disease activity, reductions in the number of relapses, and slowing of disability progression [3,4,5]. Increasing evidence suggests that the severity and rate of disease progression vary across people of different races and ethnicities [6,7,8]. Specifically, Hispanic persons with MS (pwMS) are at a greater risk of developing MS at an earlier age and have higher age and sex-adjusted disability scores compared with non-Hispanic White pwMS [9, 10], while African American pwMS exhibit more rapid MS disease progression and have a greater risk of developing severe disability compared with non-African American pwMS [10,11,12,13,14,15]. As a result, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS may benefit from initiation of heDMTs early in the disease course [16,17,18]. However, the use of specific disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) after MS diagnosis and how treatment patterns differ across pwMS of different races and ethnicities are not well understood.

This study aimed to examine the treatment patterns in a racially and ethnically diverse real-world population of newly diagnosed pwMS from a US insurance claims database.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This retrospective cohort study analyzed treatment patterns in persons thought to be newly diagnosed with MS using data from the Optum Market Clarity linked claims and electronic health records (EHR) database. The study period was from January 2015 to September 2020 (Figure S1). The Optum Market Clarity database includes de-identified data from medical and pharmacy claims and linked EHR data for > 70 million patients from > 150 US payers. The database includes persons enrolled in commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare plans.

2.2 Sample Selection

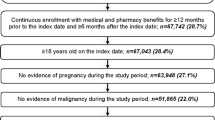

The study sample included pwMS with their first diagnosis code for MS (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification: G35) in the database on or after January 1, 2016. The index date was defined as the date of the first MS diagnosis code. To identify newly diagnosed pwMS, pwMS were required to have continuous enrollment in the claims data for ≥ 12 months prior to the index date (i.e., baseline period) and no MS diagnosis codes or use of MS DMTs prior to the index date [19,20,21,22]. The identification of newly diagnosed pwMS in this study is consistent with the algorithms used in other previously published claims-based studies of newly diagnosed pwMS [19,20,21,22]. In addition, newly diagnosed pwMS were required to have continuous enrollment in the claims data for ≥ 24 months after the index date (i.e., follow-up period), be aged 18-64 years on the index date, and have initiated any DMT approved by the FDA for the treatment of MS during the follow-up period. Persons with MS were excluded if they initiated multiple concurrent DMTs on the index date or were pregnant during the baseline or follow-up periods. In addition, pwMS who only initiated rituximab and no other DMT at any time after diagnosis were excluded since rituximab is not approved by the FDA for MS.

2.3 Data Collection

Demographic and clinical characteristics for all included pwMS were identified during the baseline period. Baseline demographic data included age on the index date, sex, geographic region, plan type, and race/ethnicity. Baseline clinical characteristics included Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), specific comorbidities, and healthcare resource use. All baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were identified using the claims data, except for race/ethnicity, which was identified from the EHR data.

All medical and pharmacy claims for MS DMTs were identified in the claims data during the follow-up period, and the index DMT was defined as the first DMT initiated after the index date. Lines of treatment were identified based on when pwMS received any new DMT according to the generic DMT name. Treatment patterns were evaluated during the follow-up period and included total months from first MS diagnosis to initiation of the index DMT, total number of lines of therapy, specific DMTs used in each line of treatment, and duration of each line of treatment. All DMTs were classified as high (alemtuzumab, cladribine, daclizumab, mitoxantrone, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and rituximab), moderate (dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, monomethyl fumarate, fingolimod, ozanimod, and siponimod), or low efficacy (glatiramer acetate, interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, peginterferon beta-1a, and teriflunomide) based on findings from clinical trials [23, 24]. Treatment patterns were described overall and stratified by race/ethnicity (i.e., non-Hispanic Black pwMS, non-Hispanic White pwMS, Hispanic pwMS, and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity). All pwMS with Hispanic as the reported ethnicity were classified as Hispanic pwMS, regardless of the reported race.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

All treatment pattern outcomes, including total months from first MS diagnosis to initiation of the index DMT, total number of lines of treatment, specific DMTs used in each line of treatment, and duration of each line of treatment, were summarized overall and in each race/ethnicity subgroup. Cell sizes < 10 were suppressed, consistent with Optum’s data use agreement. Cells ≥ 10 were suppressed as needed to avoid calculation of suppressed cells with counts < 10.

All continuous data were summarized as mean (SD), while categorical data were presented descriptively as frequency and percentages. A χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis H test was conducted to assess differences across race/ethnicity subgroups. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 Results

A total of 682 newly diagnosed pwMS who initiated any MS DMT in the 2 years after diagnosis and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the final study population (Figure S2). Among the included pwMS, 479 (70%) were non-Hispanic White, 99 (15%) were non-Hispanic Black, 35 (5%) were Hispanic, and 69 (10%) were other/unknown race/ethnicity (Table 1).

3.1 Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes baseline characteristics for all included pwMS overall and by race/ethnicity. In all newly diagnosed pwMS, the average (SD) age on the index date was 43 (12) years. Hispanic pwMS tended to be younger on the index date compared with all other race/ethnicity subgroups but there was no significant difference across subgroups (mean [SD] years, non-Hispanic Black pwMS = 43 [13]; non-Hispanic White pwMS = 44 [12]; Hispanic pwMS = 40 [12]; pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity = 42 [12]; P = 0.3).The majority of pwMS in all race/ethnicity subgroups were female and a higher proportion of Hispanic pwMS were female compared with all other pwMS (non-Hispanic Black pwMS = 71%; non-Hispanic White pwMS = 68%; Hispanic pwMS = 86%; pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity = 62%). However, there were no significant differences in sex across all race/ethnicity subgroups (P = 0.1). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in geographic region (P = 0.1), baseline inpatient hospitalizations (P = 0.5), emergency department visits (P = 0.1), MRI visits (P = 0.5), or neurologist visits (P = 0.9) across race/ethnicity subgroups. No significant differences were found in CCI scores by race and ethnicity (P = 0.09); however, non-Hispanic White pwMS tended to have fewer comorbidities compared with all other race/ethnicity groups (CCI = 0: non-Hispanic White pwMS = 81%; non-Hispanic Black pwMS = 68%; Hispanic pwMS = 66%; pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity = 78%). In addition, hypertension was significantly more common in non-Hispanic Black pwMS (36%) compared with non-Hispanic White pwMS (19%), Hispanic pwMS (20%), and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity (17%) (P = 0.002). Type of insurance coverage differed significantly by race/ethnicity, and non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS were more likely to have Medicaid insurance compared with non-Hispanic White pwMS and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity (P < 0.001).

3.2 First Line of Treatment

The specific type of index DMT did not significantly differ across race/ethnicity subgroups (P = 0.9) (Table 2). Glatiramer acetate was the most common index DMT overall and in all race/ethnicity subgroups (overall = 32%; non-Hispanic Black pwMS = 28%; non-Hispanic White pwMS = 33%; Hispanic pwMS = 31%; pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity = 32%). However, ocrelizumab was the second most frequently initiated index DMT in non-Hispanic White pwMS, while dimethyl fumarate was the second most frequently initiated index DMT in non-Hispanic Black pwMS, Hispanic pwMS, and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity.

The mean (SD) duration from MS diagnosis to the initiation of the index DMT was 4.9 (5.8) months for all pwMS. Time to initiation ranged from 4.3 (5.6) months for Hispanic pwMS to 5.5 (6.4) months in pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity but there was no statistically significant difference by race/ethnicity (P = 0.6) (Fig. 1A).

Following the initiation of the first DMT after MS diagnosis, pwMS continued to receive this first-line DMT for a mean (SD) of 16.2 (13.7) months (Fig. 1B). Across all race/ethnicity subgroups, Hispanic pwMS had the shortest duration receiving the first-line DMT (13.6 [11.8] months) compared with non-Hispanic Black pwMS (18.4 [14.2] months), non-Hispanic White pwMS (15.9 [13.7] months), and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity (16.2 [13.6] months).

3.3 Total Lines of Treatment

Overall, no pwMS received more than four lines of treatment during the two-year follow-up period; however, 78% of all pwMS received only one line of treatment in the two years following MS diagnosis (Figure S3). The total number of lines of treatment differed significantly by race/ethnicity, with 29% of Hispanic pwMS receiving ≥ 2 lines of treatment during follow-up, compared with only 16% of non-Hispanic Black pwMS, 22% of non-Hispanic White pwMS, and 24% of pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity (P = 0.04).

3.4 Initiation of heDMTs

Overall, only 27% of newly diagnosed pwMS initiated any heDMT as the index DMT. The frequency of initiation of any heDMT as a first-line treatment ranged from only 11% of Hispanic pwMS to 25% of non-Hispanic Black pwMS, 26% of pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity, and 29% of non-Hispanic White pwMS (Fig. 2A).

During the follow-up period, 37% of all pwMS initiated any heDMT in any line of treatment, and the percentage of pwMS who initiated any heDMT during follow-up was higher in non-Hispanic White pwMS (39%) and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity (41%) than in non-Hispanic Black (30%) and Hispanic pwMS (20%). Over the course of the study period, the frequency of initiation of any heDMTs as the index DMT increased from 14% in all pwMS newly diagnosed in 2014 to 39% in all pwMS newly diagnosed in 2018. The use of any heDMT as the index DMT increased over time in non-Hispanic Black pwMS, non-Hispanic White pwMS, and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity, but the initiation of heDMTs as first-line treatment remained low in Hispanic pwMS (Fig. 2B).

4 Discussion

This retrospective study examined real-world treatment patterns by race/ethnicity in newly diagnosed pwMS in the US who initiated any MS DMT in the 2 years after diagnosis. This study found that in pwMS with a diagnosis first observed in the database in 2016 through 2018 and who were enrolled with a single US insurer for 12 months before and 24 months after diagnosis, the average time from MS diagnosis to initiation of the first DMT was 4.9 months, and there were no significant differences in time to initiation by race/ethnicity. In addition, this study showed that glatiramer acetate, a low-efficacy DMT, was the most frequently initiated index DMT after MS diagnosis in all race/ethnicity subgroups. However, ocrelizumab, a heDMT, was the second most frequently initiated index DMT in non-Hispanic White pwMS, while dimethyl fumarate, a moderate-efficacy DMT, was the second most frequently initiated index DMT in non-Hispanic Black pwMS, Hispanic pwMS, and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity. Overall, pwMS continued to receive the first-line DMT for an average of 16.2 months, and only 22% had ≥ 2 DMTs during the two-year follow-up period; however, Hispanic pwMS had the shortest time receiving a first-line DMT and tended to have more lines of therapy during follow-up. Furthermore, while 37% of pwMS initiated any heDMT at any time during follow-up and the frequency of initiation increased over time, only 20% of Hispanic pwMS initiated any heDMT, and initiations remained low across the study period.

The nearly five-month delay from time to initiation of the first DMT after MS diagnosis is consistent with prior research and highlights potential barriers in accessing treatment [22, 25, 26]. Recent research found that the time to initiation of the initial DMT after MS diagnosis ranged from 3.9 months for first-line low-efficacy DMTs to 7.2 months for heDMTs but could not identify the reasons for the treatment delay [26]. This five-month delay is concerning due to research demonstrating that delays in initiation of MS treatment are associated with an increased risk of poor long-term outcomes, including disability progression [27,28,29]. Although time to initiation did not differ significantly across the race/ethnicity subgroups, differences may be obscured by the differences in the types of DMT initiated as first-line treatment, particularly since non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients tended to initiate fewer heDMTs as first-line treatment. Further research is needed to better understand the reasons for the 4.9-month treatment delay, including the potential role of insurance policies in delaying initiation of treatment, and to explore any variation in barriers to treatment by race and ethnicity.

The initiation of glatiramer acetate or dimethyl fumarate as first-line treatment following diagnosis with MS is consistent with prior literature examining treatment patterns in newly diagnosed pwMS [8, 21, 22, 30]. The use of glatiramer acetate and dimethyl fumarate as first-line treatments after diagnosis follows the escalation approach for treatment of MS, with pwMS initiating low- and moderate-efficacy DMTs first and only initiating heDMTs after experiencing relapses, new MRI lesions, or disease progression [31, 32]. Both glatiramer acetate and dimethyl fumarate have traditionally been considered first-line treatments due to their low adverse event profile but have a limited impact on disease progression [33,34,35,36]. While several studies have demonstrated that glatiramer acetate and dimethyl fumarate are safe and effective at reducing relapses in Hispanic and Black pwMS, these studies have frequently been limited by small sample sizes, and additional research has found a faster rate of disability progression in Black pwMS treated with low- and moderate-efficacy DMTs compared with other race and ethnicities [18, 37, 38].

The high frequency of initiation of glatiramer acetate or dimethyl fumarate as first-line treatments combined with the low uptake of heDMTs during the entire follow-up period contrasts with recent research demonstrating that the initiation of heDMTs early in the disease course can provide both clinical and economic benefits for pwMS by delaying long-term disease progression [3, 4, 39,40,41]. The low uptake of heDMTs both as the index DMTs and in later lines of treatment in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS is particularly notable because these populations tend to have more severe symptoms at diagnosis and more rapid progression of the severity of symptoms and disability compared with non-Hispanic White pwMS [6,7,8, 10]. African American pwMS have a shorter time to ambulation with a cane, wheelchair dependency, conversion to secondary-progressive MS, and death than non-Hispanic White pwMS, highlighting the need for early initiation of heDMTs to reduce progression [18, 42].

While the uptake of heDMTs was low during the entire follow-up period, the use of heDMTs increased over the study period in non-Hispanic Black pwMS, non-Hispanic White pwMS, and pwMS with other/unknown race/ethnicity. However, by 2018, only 43% of newly diagnosed non-Hispanic Black pwMS initiated any heDMT as first-line treatment, and uptake remained even lower in Hispanic pwMS. The low uptake of heDMTs, particularly in Hispanic pwMS, highlights the need for further research to understand the barriers to treatment in these populations of pwMS at high risk for disease progression. Prior studies have consistently demonstrated that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black pwMS experience a wide range of disparities in access to health care, including access to outpatient neurologists and MS specialists, which could impact access to heDMTs [6, 43,44,45,46]. In addition, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS were more likely to be covered by Medicaid insurance, which may include additional barriers to heDMTs due to the implementation of policies such as prior authorization, step edits, and monthly prescription limits [47,48,49]. Unfortunately, in this data source we cannot determine reasons for initiation of a treatment and cannot identify whether the high frequency of initiation of low- and moderate-efficacy DMTs is due to lack of insurance coverage for high-efficacy DMTs, differences in copayments or coinsurance across DMTs, prior authorization or step edit requirements, or the preferences of pwMS and providers. These findings highlight the need for further research to understand the barriers to uptake of heDMTs, particularly among Hispanic pwMS.

Although 78% of all pwMS in this study had only one line of treatment during the follow-up period and continued receiving the first-line DMT for an average of 16.2 months, Hispanic pwMS tended to initiate more lines of therapy during follow-up and only received the first-line treatment for 13.6 months. These findings are consistent with prior research finding low rates of persistence in Hispanic and African American pwMS initiating glatiramer acetate as well as high rates of DMT discontinuation due to disease progression [8, 50]. A shorter time receiving the index DMT and multiple lines of therapy during a two-year period are notable due to the high rates of healthcare resource use and costs associated with non-persistence to MS DMTs [51]. Although we cannot identify reasons for switching, step edit policies requiring a trial of at least several months on a lower-cost drug may contribute to the high rates of switching among Hispanic pwMS, who are more likely to be covered by Medicaid plans which frequently leverage such policies. However, additional research is needed to understand why Hispanic pwMS quickly switched to second and later lines of treatment after the first-line DMT. The observed shorter time on the index DMT combined with low uptake of heDMTs among Hispanic pwMS is consistent with prior research findings that pwMS initiating a heDMT as first-line treatment after diagnosis had a longer duration on treatment compared with pwMS initiating low- and moderate-efficacy DMTs as first-line treatment [26]. In addition, research has demonstrated that ocrelizumab, a heDMT, has significantly higher adherence and persistence compared with other DMTs [52, 53]. Therefore, with the low uptake of heDMTs in Hispanic pwMS, increasing the use of heDMTs, such as ocrelizumab, as first-line treatment should be further researched as a potential option to help address the frequent switching of DMTs.

4.1 Limitations

This study faces several limitations. First, this study is subject to limitations inherent to the use of claims data. Specifically, in claims data it is not possible to determine whether patients were truly newly diagnosed with MS on the index date. The methods used in this study are consistent with previously published claims-based studies to identify newly diagnosed pwMS, which require that patients have ≥ 12 months of continuous eligibility prior to the first observed MS diagnosis and no prior use of DMTs [19, 22]. However, it is still possible that some pwMS in this sample were previously diagnosed with MS and then did not receive any MS-related care or treatment for over one year. In addition, in claims data it cannot be determined whether pwMS who received oral or injectable DMTs took the medication as prescribed, and the reasons for initiation, discontinuation, or switching of DMTs. Second, treatment patterns are expected to differ by MS disease severity; however, measures of disease severity, such as Expanded Disability Status Scale scores, were not available during the baseline period for the majority of pwMS in this database. Third, the study relied on race and ethnicity recorded in the EHR data, which may differ from self-reported race and ethnicity and lead to misclassification [54, 55]. Fourth, this study was limited to pwMS who received any DMT in the two years after diagnosis; however, there are potentially differences in treatment rates by race/ethnicity. Fifth, the number of Hispanic pwMS included in this study was small, and results may differ in a larger, more nationally representative sample of Hispanic pwMS. In addition, it is unknown how the distribution of race/ethnicity in this study compares with the distribution in all pwMS in the US. However, the proportion of pwMS in each race/ethnicity subgroup was similar when compared with studies using other large EHR and claims databases [56, 57]. Sixth, in this study, pwMS who only initiated rituximab but no other DMTs during the follow-up period were excluded since rituximab is not approved for the treatment of MS, does not have a standardized dosing scheme, and has not been included in studies validating the identification of pwMS treated with MS DMTs in claims data [58, 59]. However, fewer than 33 pwMS (< 5%, Figure S2) patients were excluded since rituximab was the only DMT observed at any time after diagnosis so the inclusion of the pwMS treated with only rituximab would have limited impact on the results of this study. Seventh, this study only included pwMS with ≥ 36 months of continuous eligibility from a single payer, primarily included individuals with commercial insurance, and did not include uninsured patients; therefore, results may not be generalizable to all pwMS. The pwMS who were excluded due to a lack of continuous eligibility from a single payer may have been more likely to be non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic [60, 61]. However, results were similar when pwMS were only required to have ≥ 12 months of continuous eligibility after the index date. Eighth, the study only included patients with an MS diagnosis first observed at age 18–64 years, and results may not be generalizable to pediatric pwMS and adults diagnosed at age 65 or later. However, we expect the impact of the age criteria on the sample size to be small and treatment patterns are expected to differ greatly in those age groups [62,63,64,65]. Finally, this study did not include pwMS who remained untreated in the 2 years after the first observed MS diagnosis. Further research is needed to understand differences in uptake of any treatment after diagnosis by race/ethnicity.

5 Conclusions

This real-world study demonstrates that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic pwMS frequently initiate low and moderate-efficacy DMTs as first-line treatments for MS, even though these pwMS are at a greater risk of developing a severe disease course with greater disability. Although the use of heDMTs was limited across all race/ethnicity subgroups, use of heDMTs remained low in Hispanic pwMS while increasing for non-Hispanic White and Black pwMS throughout the study period. Further examination of the factors driving this low uptake of heDMTs in Hispanic pwMS is required.

Abbreviations

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- DMT:

-

Disease-modifying therapy

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- heDMT:

-

High-efficacy disease-modifying therapy

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- pwMS:

-

Persons with multiple sclerosis

References

Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, Nelson LM, Langer-Gould A, Marrie RA, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029–40. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035.

Bebo B, Cintina I, LaRocca N, Ritter L, Talente B, Hartung D, et al. The economic burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: estimate of direct and indirect costs. Neurology. 2022;98(18):e1810–7. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200150.

Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, Hrastelj J, Rimmer A, Joseph F, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):536–41. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4905.

Buron MD, Chalmer TA, Sellebjerg F, Barzinji I, Christensen JR, Christensen MK, et al. Initial high-efficacy disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: a nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e1041–51. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010135.

Simonsen CS, Flemmen H, Broch L, Brunborg C, Berg-Hansen P, Moen SM, et al. Early high efficacy treatment in multiple sclerosis is the best predictor of future disease activity over 1 and 2 years in a Norwegian population-based registry. Front Neurol. 2021;12:693017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.693017.

Amezcua L, McCauley JL. Race and ethnicity on MS presentation and disease course. Mult Scler. 2020;26(5):561–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458519887328.

Kister I, Bacon T, Cutter GR. How multiple sclerosis symptoms vary by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(4):335–41. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001105.

Pérez CA, Lincoln JA. Racial and ethnic disparities in treatment response and tolerability in multiple sclerosis: a comparative study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;56:103248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.103248.

Amezcua L, Lund BT, Weiner LP, Islam T. Multiple sclerosis in Hispanics: a study of clinical disease expression. Mult Scler. 2011;17(8):1010–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458511403025.

Ventura RE, Antezana AO, Bacon T, Kister I. Hispanic Americans and African Americans with multiple sclerosis have more severe disease course than Caucasian Americans. Mult Scler. 2017;23(11):1554–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516679894.

Weinstock-Guttman B, Jacobs LD, Brownscheidle CM, Baier M, Rea DF, Apatoff BR, et al. Multiple sclerosis characteristics in African American patients in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2003;9(3):293–8. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458503ms909oa.

Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, Vollmer T, Campagnolo D. Does multiple sclerosis–associated disability differ between races? Neurology. 2006;66(8):1235–40. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000208505.81912.82.

Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Niewczyk PM, De Guzman RA, Apatoff B, et al. Rapid disease course in African Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;75(3):217–23. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e72a.

Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Zhang JL. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in multiple racial and ethnic groups. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1734–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918cc2.

Caldito NG, Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Dewey BE, Cowley NJ, Glaister J, et al. Brain and retinal atrophy in African–Americans versus Caucasian–Americans with multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Brain. 2018;141(11):3115–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy245.

Cree BA, Stuart WH, Tornatore CS, Jeffery DR, Pace AL, Cha CH. Efficacy of natalizumab therapy in patients of African descent with relapsing multiple sclerosis: analysis of AFFIRM and SENTINEL data. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(4):464–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2011.45.

Cree BAC, Pradhan A, Pei J, Williams MJ. Efficacy and safety of ocrelizumab vs interferon beta-1a in participants of African descent with relapsing multiple sclerosis in the Phase III OPERA I and OPERA II studies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;52:103010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.103010.

Okai AF, Howard AM, Williams MJ, Brink JD, Chen C, Stuchiner TL, et al. Advancing care and outcomes for African American patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2022;98(24):1015–20. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200791.

Persson R, Lee S, Yood MU, Wagner M, Minton N, Niemcryk S, et al. Incident cardiovascular disease in patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis: a multi-database study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;37:101423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2019.101423.

Fox RJ, Mehta R, Pham T, Park J, Wilson K, Bonafede M. Real-world disease-modifying therapy pathways from administrative claims data in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02738-7.

Margolis JM, Fowler R, Johnson BH, Kassed CA, Kahler K. Disease-modifying drug initiation patterns in commercially insured multiple sclerosis patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:122. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-122.

Kern DM, Cepeda MS. Treatment patterns and comorbid burden of patients newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in the United States. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01882-2.

Samjoo IA, Worthington E, Drudge C, Zhao M, Cameron C, Häring DA, et al. Efficacy classification of modern therapies in multiple sclerosis. J Comp Eff Res. 2021;10(6):495–507. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer-2020-0267.

Lucchetta RC, Tonin FS, Borba HHL, Leonart LP, Ferreira VL, Bonetti AF, et al. Disease-modifying therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(9):813–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0541-5.

Greenfield J, Harris C, Chandler C, Metz LM. Time to initiation of disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis in Southern Alberta is decreasing. In: 33rd annual meeting of the consortium of multiple sclerosis centers. Seattle, Washington 2019.

Geiger C, Sheinson D, To TM, Jones D, Bonine N. Characteristics of newly diagnosed MS patients initiating high, moderate, and low-efficacy disease-modifying therapies as first-line treatment. ACTRIMS Forum. West Palm Beach, Florida 2022.

Wandall-Holm MF, Buron MD, Kopp TI, Thielen K, Sellebjerg F, Magyari M. Time to first treatment and risk of disability pension in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(8):858–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2022-329058.

He A, Merkel B, Brown JWL, Zhovits Ryerson L, Kister I, Malpas CB, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(4):307–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30067-3.

Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Butzkueven H, Hillert J, Hyde R, Koch-Henriksen N, et al. Early treatment delays long-term disability accrual in RRMS: results from the BMSD network. Mult Scler. 2021;27(10):1543–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/13524585211010128.

Freeman L, Kee A, Tian M, Mehta R. Retrospective claims analysis of treatment patterns, relapse, utilization, and cost among patients with multiple sclerosis initiating second-line disease-modifying therapy. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2021;8(4):497–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-021-00251-w.

Casanova B, Quintanilla-Bordás C, Gascón F. Escalation vs. early intense therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Pers Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12010119.

Fenu G, Lorefice L, Frau F, Coghe GC, Marrosu MG, Cocco E. Induction and escalation therapies in multiple sclerosis. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2015;14(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871523014666150504122220.

Liu Z, Liao Q, Wen H, Zhang Y. Disease modifying therapies in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(6):102826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102826.

Li H, Hu F, Zhang Y, Li K. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2020;267(12):3489–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09395-w.

Scott LJ. Glatiramer acetate: a review of its use in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and in delaying the onset of clinically definite multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):971–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-013-0117-3.

Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, Hutchinson M, Havrdova E, Kita M, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1087–97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1206328.

Williams MJ, Amezcua L, Okai A, Okuda DT, Cohan S, Su R, et al. Real-world safety and effectiveness of dimethyl fumarate in Black or African American patients with multiple sclerosis: 3-year results from ESTEEM. Neurol Ther. 2020;9(2):483–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-020-00193-5.

Klineova S, Nicholas J, Walker A. Response to disease modifying therapies in African Americans with multiple sclerosis. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(2):221–5. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cff6fb.

Spelman T, Magyari M, Piehl F, Svenningsson A, Rasmussen PV, Kant M, et al. Treatment escalation vs immediate initiation of highly effective treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: data from 2 different national strategies. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(10):1197–204. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2738.

Iaffaldano P, Lucisano G, Caputo F, Paolicelli D, Patti F, Zaffaroni M, et al. Long-term disability trajectories in relapsing multiple sclerosis patients treated with early intensive or escalation treatment strategies. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211019574. https://doi.org/10.1177/17562864211019574.

Geiger C, Sheinson D, To TM, Jones D, Bonine N. Real-world clinical and economic outcomes among persons with multiple sclerosis initiating first- vs second-line treatment with ocrelizumab. In: 38th congress of the European Committee for treatment and research in multiple sclerosis Amsterdam, the Netherlands 2022.

Naismith RT, Trinkaus K, Cross AH. Phenotype and prognosis in African–Americans with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective chart review. Mult Scler. 2006;12(6):775–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458506070923.

Amezcua L, Rivera VM, Vazquez TC, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Langer-Gould A. Health disparities, inequities, and social determinants of health in multiple sclerosis and related disorders in the US: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(12):1515. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3416.

Buchanan RJ, Zuniga MA, Carrillo-Zuniga G, Chakravorty BJ, Tyry T, Moreau RL, et al. Comparisons of Latinos, African Americans, and Caucasians with multiple sclerosis. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(4):451–7.

Saadi A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Mejia NI. Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology. 2017;88(24):2268–75. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004025.

Shabas D, Heffner M. Multiple sclerosis management for low-income minorities. Mult Scler. 2005;11(6):635–40. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1215oa.

Reyes S. A retrospective analysis of insurance policy impact on the choice of multiple sclerosis disease modifying therapies. 2021https://doi.org/10.7302/3516.

Bourdette DN, Hartung DM, Whitham RH. Practices of US health insurance companies concerning MS therapies interfere with shared decision-making and harm patients. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(2):177–82. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000208.

Gifford K, Winter A, Wiant L, Dolan R, Tian M, Garfield R. How state medicaid programs are managing prescription drug costs: results from a state medicaid pharmacy survey for state fiscal years 2019 and 2020. 2020.

Williams MJ, Johnson K, Trenz HM, Korrer S, Halpern R, Park Y, et al. Adherence, persistence, and discontinuation among Hispanic and African American patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod or glatiramer acetate. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(1):107–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2017.1374937.

Pardo G, Pineda ED, Ng CD, Sheinson D, Bonine NG. The association between persistence and adherence to disease-modifying therapies and healthcare resource utilization and costs in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2022;9(1):111–6. https://doi.org/10.36469/jheor.2022.33288.

Engmann NJ, Sheinson D, Bawa K, Ng CD, Pardo G. Persistence and adherence to ocrelizumab compared with other disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in U.S. commercial claims data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(5):639–49. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2021.20413.

Pardo G, Pineda ED, Ng CD, Bawa KK, Sheinson D, Bonine NG. Adherence to and persistence with disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis over 24 months: a retrospective claims analysis. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(1):337–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00319-3.

Klinger EV, Carlini SV, Gonzalez I, Hubert SS, Linder JA, Rigotti NA, et al. Accuracy of race, ethnicity, and language preference in an electronic health record. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):719–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3102-8.

Polubriaginof FCG, Ryan P, Salmasian H, Shapiro AW, Perotte A, Safford MM, et al. Challenges with quality of race and ethnicity data in observational databases. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8–9):730–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz113.

Nelson RE, Xie Y, DuVall SL, Butler J, Kamauu AW, Knippenberg K, et al. Multiple sclerosis and risk of infection-related hospitalization and death in US veterans. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(5):221–30. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2014-035.

Langer-Gould AM, Gonzales EG, Smith JB, Li BH, Nelson LM. Racial and ethnic disparities in multiple sclerosis prevalence. Neurology. 2022;98(18):e1818–27. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000200151.

Culpepper WJ, Marrie RA, Langer-Gould A, Wallin MT, Campbell JD, Nelson LM, et al. Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1016–28. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000007043.

Van Le H, Le Truong CT, Kamauu AWC, Holmén J, Fillmore C, Kobayashi MG, et al. Identifying patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis using algorithms applied to US integrated delivery network healthcare data. Value Health. 2019;22(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.06.014.

Wolf E, Slosar M, Menashe I. Assessment of churn in coverage among California's health insurance marketplace enrollees. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(12):e224484. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4484.

Kressin NR, Terrin N, Hanchate AD, Price LL, Moreno-Koehler A, LeClair A, et al. Is insurance instability associated with hypertension outcomes and does this vary by race/ethnicity? BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):216. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05095-8.

Krysko KM, Graves J, Rensel M, Weinstock-Guttman B, Aaen G, Benson L, et al. Use of newer disease-modifying therapies in pediatric multiple sclerosis in the US. Neurology. 2018;91(19):e1778–87. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006471.

Vaughn CB, Jakimovski D, Kavak KS, Ramanathan M, Benedict RHB, Zivadinov R, et al. Epidemiology and treatment of multiple sclerosis in elderly populations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(6):329–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-019-0183-3.

Greenberg B, Kolodny S, Wang M, Deshpande C. Utilization and treatment patterns of disease-modifying therapy in pediatric patients with multiple sclerosis in the United States. Int J MS Care. 2021;23(3):101–5. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2019-095.

Zhang Y, Salter A, Jin S, Culpepper WJ, Cutter GR, Wallin M, et al. Disease-modifying therapy prescription patterns in people with multiple sclerosis by age. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211006500. https://doi.org/10.1177/17562864211006499.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Support for third-party writing assistance, furnished by Sanuji Gajamange, PhD, was provided by Health Interactions, Inc. and funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was sponsored and supported by Genentech, Inc./F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Conflict of interests

CK Geiger, D Sheinson, TM To, D Jones and NG Bonine are employees of Genentech, Inc., and shareholders of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Compliance with ethical standards

This retrospective database analysis used deidentified claims data from the Optum Market Clarity® database, which is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act to protect patient privacy.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The Optum Market Clarity linked EHR and claims database analyzed during this study is not publicly available as this is proprietary information.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: all; methodology: CKG, DS, TMT, NGB; formal analysis: DS, TMT; validation: DS, TMT; project administration: CKG, NGB; supervision: CKG, NGB; visualization: CKG; writing—review and editing: all. All authors read and approved the final version.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geiger, C.K., Sheinson, D., To, T.M. et al. Treatment Patterns by Race and Ethnicity in Newly Diagnosed Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 565–575 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00387-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00387-x