Abstract

This study evaluates whether and how the services provided by Italian museums are influenced by the quality of the institutional context at the regional level. Institutional quality is measured by a range of indicators largely employed in the literature, such as the Institutional Quality Index (IQI), the European Quality of Government Index (EQI), and their components. Resorting to spatial autoregressive models, the presence of spatial dependence in museum service provision is also investigated. The analysis shows that the common institutional context is significant, especially for public museums, and it explains part of the spatial correlation among museums within regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The influence of institutions on agents’ behaviours is widely recognised in the economic literature (e.g., North 1990; Durlauf 2018; Acemoglu et al. 2019). Especially in publicly funded sectors, where agents need to be kept accountable, the quality of the institutional environment in which they operate is of primary importance. The relevance of variables related to the quality of institutions has emerged in analyses devoted to investigating, for example, the choice of hospitals (Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2003; De Luca et al. 2021), infrastructure provision (Wong et al. 2017; Guccio et al. 2019), patent activity (Wagner and Bologna-Pavlik 2020), and politicians’ misbehaviour (Nannicini et al. 2013).

This study focuses on the effect of regional institutional quality in the case of service provision by museums, taking Italy as a case study. We consider a wide set of services offered by museums, which includes services related to museum accessibility (e.g., evening opening, opening upon request, and open-house days), the support to visitors’ experience (e.g., the presence of information points, brochures, audio and video guides), and the presence of on-line services (e.g., the presence of websites, online ticket purchases, online bookshops or merchandising).

Most museums in Italy are public and, more generally, the cultural sector is largely publicly funded. While a few studies relating to the effects of changes in national rules on museum performance in Italy are available (see, e.g., Alfano et al. 2022; Bertacchini et al. 2018, on the effects of managerial autonomy; Cellini and Cuccia 2018, on the effects of entrance pricing policy), the role of local institutions is overlooked. Service provision is an aspect over which Italian museums have some degree of autonomy, and, as such, they could be affected by the quality of the local institutional context.

We measure the quality of local institutions by considering a range of indicators largely employed in the economic literature, such as the Institutional Quality Index (IQI) and the European Quality of Government Index (EQI); these indicators take into account both the functioning of formal institutions and informal institutions related to individual and collective behaviour. All institutional quality indicators show large variations across Italian regions, which makes Italy a suitable case study (e.g., Nannicini et al. 2013; Charron et al. 2014; De Luca et al. 2021). We find that several regional indicators, including those related to corruption, government effectiveness, and citizen participation, are significant determinants of museum service provision, especially in public museums.

Resorting to spatial autoregressive models, we also investigate the nature of spatial dependence. Spatial effects in museum service provision have been recently documented by Cellini et al. (2020), in the absence of variables capturing the role of institutions and their quality. Different interpretations can be provided regarding the economic meaning and sources of these spatial effects. The extended empirical framework of the present analysis allows us to evaluate whether the spatial dependence in museum services is motivated by common institutional factors or has to be associated with different motives. Our analysis indicates that spatial dependence in museum services may be due to some common features at the regional level (i.e., ‘correlated effect’, borrowing the label from Manski 1993, 2000), instead of being due to ‘endogenous effect’, such as imitation or competitive motives among museums. This seems to be consistent with the Italian cultural sector, in which the great majority of museums depend on the reference regional authority (the so-called Soprintendenze), while competition does not seem to play a major role (e.g., Bertacchini et al. 2018; Cellini et al. 2020). However, spatial autocorrelation at the regional level continues to be statistically significant, even after controlling for common institutional factors. Overall, our analysis suggests that the common institutional context in which museums (especially public museums) operate is a key determinant in museum service provision.

This study aims to contribute to different strands of the literature. First, it contributes to the body of empirical studies documenting that the quality of local institutions significantly affects the choices of subjects located in an area (see, e.g., Nannicini et al. 2013; De Luca et al. 2021). In this regard, we show for the first time that museum services are also affected by the local institutional quality. Second, our study contributes to the specific literature on cultural economics concerning museums as institutions that meet both private and public demands. Beyond market-oriented activities, museums are expected to play a role as institutions endowed with social responsibility towards current and future generations (OECD-ICOM 2019). The present study complements the available literature concerning the determinants of museum service provision (see, e.g., Bertacchini et al. 2018; Cellini et al. 2020), thereby highlighting the effect of the local institutional context in which museums operate. A related strand of the literature analyses the technical efficiency of museums (see e.g., the recent contributions of Beretta et al. 2019; Del Barrio-Tellado and Herrero-Prieto 2019, 2022; Guccio et al. 2020); our present research does not deal with the measurement of technical efficiency, but our results suggest that local institutions may also play a role in shaping museums’ technical efficiency.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents a case study of Italian museums and discusses the potential mechanisms through which institutional quality could affect services provision by museums. Section 3 presents the data. Section 4 describes the empirical strategy. Section 5 presents the results of our empirical analysis. Section 6 concludes.

2 The Case of Italian Museums: Institutional Quality and Spatial Correlation

Museums are institutions that aim to preserve tangible and intangible heritage for the purposes of education, study, and enjoyment (ICOM 2007). Museums provide goods and services that serve both private and public demands. Private demand is typically expressed by individuals (residents and tourists) who visit museums for cultural or professional purposes. Social demand is expressed by local (and national) communities who ask museums to protect symbols of cultural identity (Frey and Meier 2006) or contribute to the regeneration of urban areas (see, e.g., Plaza 2006; OECD-ICOM 2019). The multitasking nature of museums is a matter of fact, and the range of services provided by museums has increased significantly in recent times.

The Italian case is largely studied because Italy has approximately 5000 museums, and since 2011 a detailed survey has been conducted concerning the offered services. By ‘museums’, herein, we intend not only museums stricto sensu but also similar institutions (i.e., galleries, monuments, historical parks and areas, and archaeological sites), as defined by the Italian National Statistics Institute (ISTAT 2021).

Among the recent analyses on the choices of Italian museums concerning offered services, Bertacchini et al. (2018) and Cellini et al. (2020) document that the number and type of services crucially depend on the characteristics of museums. For instance, private or privately managed museums appear to offer more services than government museums.Footnote 1 Galleries provide more services than monuments, archaeological areas, or parks. Being part of a network also drives museums to increase the number of services they offer. The mentioned studies also show that museum size—as measured by the surface or employees—is associated with a higher number of services (this is not surprising, as some services are space-consuming, and size could be a proxy of available resources). Context variables, such as the resident population and tourist accommodation structures, at the regional or provincial level, do not seem to have a positive and significant effect on the number of offered services: see, specifically, Cellini et al. (2020, p. 548–50) and some specifications in Bertacchini et al. (2018, p. 631–34), the same result emerges from the analysis in Dalle Nogare and Scuderi (2020) on the museum activities related to hosting events. This lack of significance of resident population and tourist accommodation structures could lead to the conclusion that the pressure deriving from external factors is limited.

Notably, spatial autoregressive factors are significant for museums located in the same region, in explaining the number of offered services: this is documented, in particular, by Cellini et al. (2020). The significance of spatial correlation can be due to different factors (Manski 2000). It could be due to imitation or competition, but also common factors shared by museums located in the same area, such as common regional rules. For this reason, it is important to assess how spatial correlation interacts with the role of common institutional factors at the local level (herein, ‘local’ is intended as ‘regional’, if not differently specified).

Available analyses on service provision omit the role of local institutions and their quality in shaping museums’ choices. We believe that this aspect is of fundamental importance towards understanding museum choices. The quality of institutions is a broad (multidisciplinary) latent concept. Hereunder, the possible role of institutional quality in affecting museums’ behaviour is discussed following the standard classification of its ‘dimensions’ provided by the most well-known measure of institutional quality, namely the ‘World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators’ (Kaufmann et al. 2010): voice and accountability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, control of corruption.

The voice and accountability (VA) in a local environment capture the extent to which citizens are active in monitoring local governments in the use of public resources. In general, a high level of VA is deemed as crucial to stimulate the provision of public services (Nannicini et al. 2013). In the case of museums, the increasing awareness of citizens of the social and economic role that museums can locally play enhances higher citizens’ voice that might give rise to a higher demand for museum services, thus stimulating a larger provision of museum services.

The government effectiveness (GE) refers to the administrative capacity of local government and its civil servants to implement policies and provide public services effectively and efficiently. It is worth noting that most museums in Italy are public and, as such, they have to interact with (and depend on) the reference regional authority (e.g., Bertacchini et al. 2018; Cellini et al. 2020); thus, their behaviours may be influenced by the quality of governance in the region. Lower government effectiveness of regional public administration might lead museums to refrain from increasing their number of services. Furthermore, museum services have a relevant public-interest nature (e.g., Frey and Meier 2006); thus, a better public governance might devote more attention to the provision of museum services.

The dimension of regulatory quality (RQ) concerns the ability of local government to implement effective regulations that attract private investments, sustain the private sector development and promote public–private cooperation. As far as the museum service provision concerns, a better RQ favours the participation of the private sector in supplying services, and public–private partnerships to access public funds. A better quality of market regulation might reduce administrative costs and favour the presence of private firms in the area, increasing competition and thus the provision of museum services. Recent contributions, however, have cast doubts on the current extent of competition in the Italian museum services (e.g., Cellini et al. 2020).

The rule of law (RL) refers to the extent to which agents have confidence in the rules of society and trust policies, local administration, and the courts. In general, there is large consensus on the importance of RL in fostering the economic development (Haggard and Tiede 2011). As to the provision of museum services, confidence in administrative authorities’ decision-making and in courts make the managers of museums more confident in making decisions; on the opposite, the absence of such confidence may drive museum managers—and especially the manager of the museums under the control of public administration—to restrain decision-making, and consequently to restrain the provision of services whose production requires acts subject to administrative control. More in general, the confidence in the enforceability of contracts and agreements may enhance the service provision.

The level of corruption (CC) in the institutional environment concerns the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain. The complexities in evaluating performance as well as the difficulties in recovering information by the citizens might make the cultural sector potentially prone to corruption practices (Rose-Ackerman 1997). As usual, this might represent an extra tax burden for those firms which have to interact with (and depend on) a corrupt public administration (e.g., Dal Bó and Rossi 2007; Yan and Oum 2014), as it is the case for public museums. Hence, as said for GE, a corrupt regional public administration might lead museums to refrain from increasing their services, or might be an obstacle for appropriate service supply.

Finally, a correct interpretation of the significance of spatial autoregressive factors needs to assess which effect is exerted by some common variables, such as institutional quality, shared by museums in the same context (e.g., Elhorst 2014). In the absence of a control for such variables, significant spatial effects could emerge simply because museums located in the same area share the same institutional environment or rules designed by the local public administration. In the present analysis, we focus on the role of institutional quality in determining the number of services offered by museums; admittedly, nothing can be said about their effectiveness in increasing visitors’ experiences.

3 Data

3.1 Museum-Level Data

The main source of data in our empirical analysis is the census on museums and similar institutions (Indagine sui musei e le istituzioni similari) provided by ISTAT, which collects information on the types of services and activities provided by each museum. The most recent and complete census used in the present analysis refers to museums in 2018 (ISTAT 2021), which includes 4445 museums. Only the museums for which all the necessary data are available are included in the sample under consideration in the present analysis; thus, the sample at hand comprises 2025 museums. As shown in Table 1, the distribution of the sample closely mimics the features of the universe.

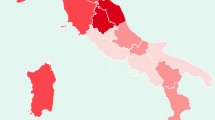

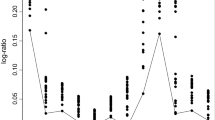

Inspired by Cellini et al. (2020), we consider 40 possible services and activities for each museum, and the full list of services under present consideration is reported in Table 2. Generally speaking, services related to museum accessibility (such as evening opening or opening upon request) and the presence of web services (such as websites, online tickets and bookshops) have a public-good nature, whereas services supporting visitor experience are, in many cases, of a private nature. On average, the museums in the dataset offer approximately 20 services (mean value is 19.91, corresponding to 49.77% of the considered services), with a large variability across museums (standard deviation is 6.23). Among Italian regions, the highest numbers of services on average are found in Emilia-Romagna (21.3) and Campania (21.2), thus showing the absence of a clear-cut North–South dualism. The worst-performing regions are Molise (14.5) and Sicily (16.7).

3.2 Institutional Quality and Its Measurement

Institution is a wide concept that is difficult to define. It includes both elements of private behaviour common to individuals (i.e., behavioural norms) and formalised rules. However, the measurement of institutional quality raises some issues regarding the selection of the appropriate approach to be used. For instance, perception measures are subjective and prone to cognitive bias, whereas evidence-based measures may generate problems depending on the collection of data (e.g., Sequeira 2012; Voigt 2013). In this analysis, we consider two different indices, both largely used in the literature: the Institutional Quality Index (IQI) proposed by Nifo and Vecchione (2014),Footnote 2 with its sub-components, and the European Quality of Government Index (EQI), with its sub-components (Charron et al. 2014, 2015). While the IQI is based on observable variables, and all the data for its computation are collected from Italian institutional sources and research institutes, the EQI derives from interviews and questionnaires that capture subjective evaluations.

More specifically, the IQI is a synthetic index composed of five different sub-components of the quality of institutional environment. The five sub-components of the IQI are the same five dimensions of institutional quality discussed in Sect. 2 (Nifo and Vecchione 2014): (1) voice and accountability (IQI_VA); (2) government effectiveness (IQI_GE); (3) regulatory quality (IQI_RQ); (4) rule of law (IQI_RL); (5) control of corruption (IQI_CC). It adopts the hierarchical framework of Kaufmann et al. (2010) to aggregate different aspects of the performance of local governance at the provincial and/or regional level. Therefore, the five components are combined into a unique measure using the analytic hierarchy process developed by Saaty (1980).Footnote 3 By construction, the index ranges from 0 (worst institutional context) to 1 (best institutional quality value). We also adopt an alternative version of the IQI index (labelled as IQI_EW) that assigns equal weights to the five components; all substantial results are robust to this modification in the index computation.

The IQI is available at the regional and provincial levels.Footnote 4 In the present analysis, it is considered at the regional level to be consistent with the institutional features of the Italian cultural sector. The most recent available computation of the IQI refers to data in 2019; here, we use data from 2017 to be consistent with the EQI data (see below). Moreover, given the structural nature of these institutional variables (Acemoglu and Robinson 2008; Kaufmann et al. 2010; Nifo and Vecchione 2014), and the fact that we deal with cross-sectional data, the one-year time disalignment between the observation of services offered by museums and the institutional quality variables is not a serious problem. Conversely, it can be seen as an element of strength of our estimates: the quality of institutions is investigated as a predetermined explanatory factor.

The other indicator of institutional quality, EQI, is developed by the Quality of Government Institute of the University of Gothenburg (see Charron et al. 2014, 2015). It is based on a survey conducted at the regional level in Europe, in 2010, 2013, and 2017. The EQI combines three different dimensions: the quality (EQI_QL), impartiality (EQI_IM), and corruption (EQI_CC) of public servants. The index ranges from -2.88 to 1.75, where higher values indicate higher quality of governance.Footnote 5 The present analysis considers the 2017 data.Footnote 6

4 Empirical Strategy

4.1 Instrumental Variable Approach

Our empirical analysis aims to investigate whether institutional quality has a significant impact on museums’ behaviours in terms of the number of services offered. The baseline regression model is:

where \({y}_{i,p,r}\) is the number of services (N_SERV), out of the 40 possible services under consideration, provided by museum i, located in province p, belonging to region rFootnote 7; QIr is the variable measuring institutional quality at the regional level; \({{\varvec{X}}}_{{\varvec{i}},{\varvec{p}},{\varvec{r}}}^{1}\) is a vector of control variables at the museum level, describing the ownership type and the organizational structure of museum institutions, along with other structural individual features; \({{\varvec{X}}}_{{\varvec{p}},{\varvec{r}}}^{2}\) is a vector of control variables at the provincial level; \({\varepsilon }_{i,p,r}\) denotes a normally distributed error term.

As mentioned, we employ a range of institutional quality indicators. Therefore, the institutional quality index (QI) is the synthetic IQI or EQI, as well as the five IQI sub-indices (i.e., IQI_VA, IQI_GE, IQI_RQ, IQI_RL, and IQI_CC) or the three EQI sub-indices (i.e., EQI_QL, EQI_IM, and EQI_CC). The list and description of the control variables included in our regression equations are reported in Table 3 (Panel B), along with descriptive statistics. Overall, the list of control variables includes the variables considered by the available literature on museum service provision, notably by Bertacchini et al. (2018) and Cellini et al. (2020).

Despite the predetermined measures of institutional quality as well as the extensive list of controls in our empirical analysis, we cannot exclude the presence of omitted factors in (1) affecting both the number of services provided by museums and the quality of institutions. Moreover, there may be measurement errors in the institutional quality indicators. Therefore, we employ an IV strategy similar to that employed by Tabellini (2010) and De Luca et al. (2021).

As argued by influential literature (e.g., North 1981; Acemoglu et al. 2001; Tabellini 2010; Guiso et al. 2016), current institutional quality is also a by-product of historical dynamics. Therefore, we exploit the effects of past institutional and cultural traits in Italian regions as an exogenous source of variation in current institutional quality (Tabellini 2010; De Luca et al. 2021). Specifically, the first-stage regression of our IV approach is:

where \({{\varvec{z}}}_{{\varvec{r}}}\) is the vector of historical instruments. Specifically, we employ two instruments, borrowed from Tabellini (2010). The first historical variable, HIST_INSTIT, is an indicator of the ‘quality of political institutions in the period from 1600 to 1850’, measured by the ‘institutionalised constraints on the decision-making powers of chief executives’. As described in Tabellini (2010), this indicator is built so that more constraints on the powers of executives lead to a higher value of the indicator. The second historical variable, LITERACY_1881, is the ‘percentage of the population over six years old who were able to read in 1881’. Tabellini (2010) claims that these two variables capture sufficiently well the heterogeneity in historical traits (HIST_INSTIT the institutional traits, LITERACY_1881 the cultural traits) across regions before the Italian unification. The same empirical strategy based on historical instruments has been recently employed by De Luca et al. (2021) to study the effect of institutional quality on hospitals’ service provision. IV estimation is performed through standard 2SLS regression on (1) and (2).

The intuition behind this IV strategy builds on the main mechanisms through which past political institutions and cultural traits influence the functioning of current institutions. According to prominent strands of literature (e.g., Putnam et al. 1993; Acemoglu et al. 2001; Acemoglu and Robinson 2008; Tabellini 2010; Guiso et al. 2016), past political institutions have shaped local culture and governance, thus influencing the current institutional quality. As far as our second instrument concerns, low literacy facilitates manipulation from the elites, because it reduces cultural dissemination and thus constrains the ability of individuals to understand their social and institutional environment. Conversely, widespread literacy increases the participation of individuals to the public life, strengthening the well-functioning of formal institutions (Lipset 1959; Almond and Verba 1963). Hence, past political and cultural traits in Italian regions may have contributed to shape current institutional quality.Footnote 8 As a preliminary evidence, Table 4 reports pairwise correlations between institutional quality indicators and the variables representing historical instruments in our dataset. Correlation coefficients are always positive and significant. This piece of evidence supports in the first place the empirical strategy of using historical variables as instruments for current institutional quality.

This IV approach is valid if the error term in the second-stage Eq. (1) is orthogonal to the excluded historical instruments. Looking at our dependent variable in (1), there seems to be no clear-cut mechanism leading to a correlation between museum services and our historical instruments, other than that induced through the effect of current institutional quality. Therefore, controlling for a large set of control variables, our exclusion restriction appears to be plausible. Moreover, in our empirical analysis we test for over-identifying restriction, exploiting the fact that we have two historical instruments for one endogenous variable.

4.2 Spatial Auto-Regressive Models

We also aim to investigate the presence and, if any, the source of spatial dependence in museum services. In particular, we would like to evaluate whether spatial dependence is explained by the common institutional context. As for the spatial specification, the spatial literature usually suggests starting with a simple SLX specification including the spatial lag of the explanatory variables, which is indeed robust to the critiques related to identification of the spatial component, and then making model selection (e.g., Corrado and Fingleton 2012; Halleck Vega and Elhorst 2015). Therefore, we start with the following SLX modelFootnote 9:

The term \({\varvec{W}}{X}_{i}\) captures the spatial lag of the explanatory variables (i.e., spill-over effect), and it is shaped by the neighbourhood effect implicitly assumed by the spatial weight matrix \({\varvec{W}}\). The element \({w}_{ij}\) of the spatial matrix \({\varvec{W}}\) indicates the potential interaction effect between units i and j, and the strength of the spatial effect is given by the unknown spatial parameter \(\rho \) that must be estimated. It is worth noting that in our application the main explanatory variable of interest, namely institutional quality, cannot be included in the spatially lagged explanatory variables in (3), since it is an environmental variable shared among neighbouring museums (at least, this is the case for the great majority of units in the dataset); therefore, in (3) we include the spill-over effect of the characteristics of neighbouring museums. Consistent estimation of the SLX can be carried out either by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) or maximum likelihood (ML).

Then, we also specify the following Spatial Auto-Regressive model with Auto-Regressive disturbances (SARAR) (Anselin and Florax 1995):

The SARAR model includes the spatial lag of the dependent variable, \({\varvec{W}}{y}_{i}\), and also allows for spatial autocorrelation in the error term \({u}_{i}\), which is shaped by the spatial weight matrix \({\varvec{M}}\) and parameter \(\lambda \) to be estimated. Innovations \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) are assumed to be independent but potentially heteroscedastically distributed. Consistent estimation of the SARAR model can be carried out by maximum likelihood (ML) with independent and identically distributed innovations (Lee 2004) and by generalised spatial two-stage least squares (GS2SLS) in the heteroscedastic case (Kelejian and Prucha 2010).

As in many applications, we consider \({\varvec{W}}={\varvec{M}}\). Consistent with our research question, the spatial weight matrix is given as follows (i.e., binary contiguity within region, row-standardised)Footnote 10:

where \({r}_{i}\) is the region where museum i is located, and \({n}_{r}\) indicates the total number of museums located in region \(r\). According to (6), the spatial lags in the explanatory variables are the average of museum characteristics in the same region; similarly, the spatial lag in the dependent variable is the average number of services provided by other museums (with respect to i) in the same region. Intuitively, while the spatial lags in museum characteristics represent local spill-over effects, the spatial lag in the dependent variable relates the number of services in each museum to the average number of services provided by neighbouring (i.e., within the same region) museums, and can be interpreted as an ‘endogenous effect’ in service provision (e.g., Elhorst 2014). Finally, the spatial autocorrelation in the error term (5) may capture some common factors (not controlled for in the empirical specification) within the same region which lead museum services to be spatially correlated (e.g., Elhorst 2014). From the general SARAR model (4) and (5), if \(\lambda =0,\) the SAR model obtains; if \(\rho =0,\) the spatial error model (SEM) obtains.

Estimating a SAR model like (4), but without institutional quality \({QI}_{r}\) in the empirical specification, Cellini et al. (2020) found that the spatial coefficient \(\rho \) is strongly significant, uncovering the presence of spatial dependence in museum services. However, Cellini et al. (2020) cast several doubts that such significant spatial correlation could be due to spatial spill-over related to sound competition or imitative behaviour among museums, because of the institutional characteristics of this sector in Italy. That is, borrowing the standard classification proposed by Manski (1993, 2000)Footnote 11 and retraced by Elhorst (2014) for the classification of spatial regression models, doubts can arise about the fact that such neighbourhood correlation is fully attributable to ‘endogenous interactions’ among museums. Thus, including the institutional quality at the local level and estimating a sufficiently large set of spatial specifications allow us to investigate whether the neighbourhood correlation among museum services can also be attributed to other sources, such as a ‘correlated effects’ due to some common factors at the regional level (for instance, due to the common institutional context), instead of being due to ‘endogenous interactions’ among museums.

5 Results

The basic results of the OLS model in the absence of spatial autocorrelation effects are presented in Table 5.Footnote 12 Individual features of museums matter, and the results that have emerged in available analyses, with reference to previous waves of the census, are confirmed (e.g., Bertacchini et al. 2018; Cellini et al. 2020): private museums, autonomous governmental museums, and museums with outsourced management tend to offer more services, being part of a network also leads museums to offer a larger number of services, size matters, and so on. Besides, cultural institutions owned by local governments show a higher number of services than other public suppliers. Context variables such as tourism infrastructures or the total number of museums in the province are not statistically significant. It is remarkable that the sign and statistical significance of the control variables are the same as those in Bertacchini et al. (2018) and Cellini et al. (2020): this should not be given for granted, as the three contributions exploit three different waves of the Italian museum census. The consistency of the results over time confirms the robustness of the conditional correlations under scrutiny.

Regarding the novelty elements of the present analysis, both the synthetic indices IQI and EQI have a positive and statistically significant coefficient. This is a noteworthy result: the quality of the institutional context at the local level does affect the number of services offered by museums. Here, institutions are intended in a broad sense, including both local political institutions and the local community, to which museums must be accountable.Footnote 13

All the specific components of both synthetic indices are positive and statistically significant at the 1% or 5% level. We observe that significant institutional factors are related to potential demand. More specifically, the IQI_VA is related to civic participation and citizen voice, as well as social capital and cultural liveliness; cultural institutions such as museums are landmarks of local identity; thus, it is not surprising that the more significant the citizen voice, the stronger the demand for museums to play a role in the local cultural and social life, and hence the more qualified the services offered by museums. As stated by Moreno-Mendoza et al. (2020), stakeholders and active citizen participation play an increasing role in shaping museum decisions. The IQI_RQ is related to different dimensions of economic liveliness and entrepreneurship; it has to do with propensity to innovation and it is not surprising that museums are called to more active roles where local communities are more innovation oriented (see the discussion in Dalle Nogare and Murzyn-Kupisz 2021).

On the other hand, some other institutional factors are more related to the quality of the institutional environment in which suppliers operate. The IQI_RL is related to the quality of law enforcement in general, and the IQI_CC is specifically related to corruption and crime against public administration. While it is true that according to the available literature, the effects of corruption on economic performance may be mixed, negative effects are predominant in the case of government contracts (Adomako et al. 2021). In the case under scrutiny, outsourced services are attributed to public museums through public procurement procedures; thus, it is not surprising that the lower the spread of corruption, the better the service provision. Moreover, in a more corrupt institutional environment, museum managers might be less oriented towards extending the range of services provided. The IQI_GE is related to the ability of the local administration to provide social and physical infrastructures (including ICT); thus, it is not surprising that museum service provision is easier when material and immaterial structure endowments are richer.

All the aspects related to IQI sub-indices can be easily interpreted as ‘qualitative’ stimulus, to which museums located in the same area respond in a similar way.

Finally, the three EQI sub-indices (i.e., EQI_QL, EQI_IM, and EQI_CC) are related to the perceived quality of public administration in providing public services; all are positive and significant, at least at the 5% level (see Table 11 in the Appendix). Therefore, this part of the analysis indicates that both the quality of potential demand and the quality of the institutional environment in which suppliers operate matter for museum service provision.

Note also that hospitality infrastructure endowment, which is a fundamental tool to attract tourism flows, is not significant on the number of offered services. This can be interpreted as a sign of coordination failure between museum management and local development policies.

It is worth recalling that Guccio et al. (2020), using a generalised conditional efficiency model, find that context variables, specifically per capita income levels and hospitality infrastructure endowment, do affect the efficiency of Italian museums. However, Guccio et al. (2020) measure efficiency by considering only opening days and temporary exhibitions as museum output. These results are not at odds with our outcomes: the demand pressure seems to affect the choice of museums of whether or not being operative, but it does not affect the offered services, while the quality of institutions, including qualitative aspects of local demand, appears to affect the offered services.

Results are substantially confirmed by the IV estimates (Table 6). It is worth underlining that resorting to an instrumental variable approach is a precautionary choice here: there seems to be no mechanism leading to an endogeneity bias in the estimates of the effect of predetermined local institutional quality on museum services, though measurement errors in the institutional quality variables may be present. In the first-stage regressions, the coefficients of the historical instruments are positive and statistically significant, providing support for the arguments at the basis of our IV strategy. Looking at the diagnostic tests, the F-statistics of Kleibergen–Paap’s test for weak identification indicates that our instruments are not weak.Footnote 14 The p-value of the Hansen’s J statistics for over-identification restrictions supports the orthogonality condition in every specification (i.e., the error term in the second-stage equation is orthogonal to instruments), while the standard endogeneity tests do not reject the null hypothesis that QI indicators can be treated as exogenous at any significance level.

Looking at the coefficients of interest in Table 6, we again find that the quality of institutions matters, with positive and significant coefficients for all institutional quality variables under present consideration.

We now move on to the spatial analysis. Table 7 shows the results of different spatial econometric models (SLX, SEM, SAR, and SARAR) when the synthetic index IQI is considered.Footnote 15 Regarding model selection, both the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) unanimously show a clear preference for the SEM.Footnote 16 This suggests that spatial dependence in museum services may be mainly due to common features at the regional level (i.e., ‘correlated effect’ à la Manski 2000), instead of being due to some ‘endogenous effect’ among museums (such as imitation or competitive motives).

Table 8 reports the SEM (i.e., the preferred spatial specification) with all the range of institutional quality variables. All institutional quality variables are positive and significant, with marginal effects slightly higher than those in Table 5 without spatial effects.Footnote 17

From this evidence, we can infer that part of the spatial effects characterising Italian museum service provision is attributable to common aspects related to the quality of regional institutions faced by museums located in the same area. However, these common factors do not explain the entire spatial correlation, part of which can be attributed to different motives. Common procedures, common private providers, similar contracts with private providers, and other common institutional and cultural aspects at the regional level, which are not captured by our range of institutional quality variables, can be among the different motives originating spatial correlation.

Let us underline that Italian private providers of museum services are few and operate nationwide; the absence of competition in these markets, and the low frequency of races for providing public museums with complementary services have been recently denounced also by the Italian Court of Auditors (see Cellini et al. 2020).

On the other hand, the fact that tourism accommodation infrastructure and the number of museums in the province are not significant explanatory factors in the estimates drives the belief that competition for gaining more visitors plays only a minor role. These outcomes may also suggest that museum managers are only partially aware of the role of museums as tourism attractors, and that they consider collection preservation, rather than visitor attendance, as the main goal of museums.Footnote 18

It is interesting to report that the effect of institutional quality variables on the number of offered services is driven by publicly owned museums: the interactions between the quality of regional institutions and the dummy variables capturing the private or public ownership of museums (i.e., IQ*PUBLIC and IQ*PRIVATE) show that institutional quality affects the number of services provided by publicly owned museums, while the effect is usually not statistically significant (though still positive) for privately owned museums (see Table 9). This result is not surprising: public museums interact with public administrations (in particular, with regional administrations in the case of museums), and thus the quality of the institutional context is mainly relevant for these museums.

Finally, if the spatial effect and endogeneity issues are considered simultaneously in the SEM specification, as in Table 10, the institutional quality variables maintain positive and highly significant coefficients.Footnote 19 Therefore, our conclusions remain confirmed. In general, and beyond any doubt, the quality of the institutional environment in which suppliers operate, as measured by the considered indices, does matter in museums’ service provision.

6 Conclusion

We have documented that variables related to the quality of regional institutions matter in affecting the number of services offered by Italian museums, especially for public museums. Thus, museums can be added to the list of subjects (along with, for example, hospitals) for which the quality of institutions has proven to significantly affect the suppliers’ individual behaviour. Furthermore, our analysis suggests that a common institutional environment at the local level (i.e., correlated effect à la Manski 2000) contributes to the emergence of spatial correlation among neighbouring museums, while endogenous effects due to, for instance, imitation or peer competition among managers play only a minor role, at least in the case of Italian museums. In particular, we have found that indices related to citizens’ voice, the ability of local governments to provide material and immaterial infrastructure, and limited corruption are significantly correlated with the number of services provided by museums and capture part of the spatial correlation among museums. However, spatial autocorrelation in the error term still remains, even after controlling for the abovementioned institutional factors. These results are robust to all the considered regression model specifications.

The evidence we have found for museums may also hold for several public services, where in many cases spatial effects are significant and institutions and their quality do matter. In all cases, disentangling the spatial autocorrelation due to common institutional factors is important to provide an appropriate interpretation of spatial autocorrelation.

As a final point and a policy prescription, we observe that museum managers should be aware of the multiple roles they can play. For instance, it is remarkable that context variables related to tourism (namely, the accommodation infrastructure endowment) and potential competitive pressure (namely, the total number of museums) are not significant for the offered services. This is also a sign of poor coordination between cultural, tourism, and development policies. Policy coordination is an aspect of institutional quality that is not investigated in the present analysis and deserves further attention.

In general, we are aware that several dimensions of institutions are overlooked by the indices considered in this analysis. Of course, the consideration of such dimensions could help explain the remaining part of spatial autocorrelation within regions. We leave this for future research, once more indices of institutional quality are available.

Data availability

The data analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

In Italy, since the Ronchey Law in the mid-1990s, services in government museums can be outsourced, with an increased role for private providers. In general, a series of reforms over the last three decades have enlarged the degree of autonomy for public museums: they can resort to outsourced services, and a group of ‘superstar’ museums benefit from the technical, scientific, and managerial autonomy. See Leva et al. (2019) and Alfano et al. (2022) for a short history and an empirical analysis of the effects of such institutional reforms on the performance of Italian museums.

See Nifo and Vecchione (2014) for details on the weights and specific components of each sub-indicator. See also the website https://sites.google.com/site/institutionalqualityindex for further details.

Twenty regions and one hundred and seven provinces are present in Italy.

By construction, the average value of the EQI indicator across European regions is equal to 0.

See Ganau and Rodriguez-Pose (2019) for an analysis of the effect of the EQI on firm productivity across Western European regions.

The dependent variable y (the number of services offered by museums) is a count variable, while the standard linear regression model is appropriate when the dependent variable is continuous. However, available studies show that a count random variable can be well approximated by a normal random variable when the expected count is sufficiently large, namely, greater than 10. In the case at hand, the mean number of museum services in our sample is 19.91; this suggests that the specification of the linear regression model (1) could be appropriate in this empirical application (Griffith 2006; Cellini et al. 2020).

For an extensive discussion of the IV strategy based on historical instruments, see De Luca et al. (2021).

Variable subscripts are simplified: any museum i belongs to province p within region r.

It is worth noting that unavailability of data on the precise location of museums would prevent us from specifying more standard distance-based spatial weight matrixes. In our application, however, the spatial matrix (6) allows us to test for the presence of spatial dependence due to the shared institutional context among museums with the same region. Nonetheless, as a robustness check, we have also built a row-standardized inverse distance matrix expressed in kilometers using the latitude and longitude coordinates of the municipalities in which cultural institutions operate (we put a unitary value for institutions within the same municipality). Our conclusions are fully confirmed by this alternative specification of the spatial matrix. Results are available upon request from the authors.

In his seminal article on the economic analysis of social interactions, Manski (2000) suggests that neighbourhood effects can be due to three types of interaction among neighbours: (i) endogenous interaction, that is, the propensity of an agent to behave in a given way varies with the behaviour of the group to which he/she belongs (e.g., competition effect, peer effect); (ii) contextual interaction, where individual behaviour is determined by the exogenous features of the reference group (e.g., similar cultural traits); (iii) correlated effects, which emerge when agents in the same group behave similarly simply because they share common unobservable factors (e.g., similar institutional context).

For reasons of space, the tables in the text report the results for the specifications with the synthetic IQI index and its sub-indices, while the specifications with IQI_EW, synthetic EQI and its sub-indices are reported in the Appendix. Overall, the results from these latter specifications are fully in line with those using the IQI and its sub-indices, reported in text.

See Dalle Nogare et al. (2021) for a recent model on accountability of museums towards their local sponsors and visitors.

First-stage estimates are available upon request.

The same preference for the SEM holds when we estimate the SLX model by introducing one explanatory variable at a time, as well as by taking into account the other indicators of institutional quality. In those cases, the coefficients of IQ turn to be positive and statistically significant in every specification.

In spatial models, the marginal effect of an explanatory variable (e.g., IQI) on unit i’s dependent variable is not generally equal to the estimated coefficient, given the simultaneous feedback effects from the changes in neighbours j’s dependent variable that arise from the change in the explanatory variable (Le Sage and Pace 2009). Hence, the total effect of an explanatory variable can be disentangled in direct effect (i.e., the first-order effect of the explanatory variable on unit i’s dependent variable) and indirect effect (i.e., the simultaneous feedback effect given by the changes in neighbours j’s dependent variable). However, since the SEM does not include the spatial lag, the simultaneous feedback effect is not present, and thus the marginal effect of the explanatory variables is equal to the estimated coefficient as in linear regression model. For the sake of completeness, in Appendix (Table A.6) we report the same estimates with the SAR specification (i.e., with the spatial lag in the dependent variable), disentangling the total effect of the institutional quality variables in direct effect and indirect effect. As for the effects of institutional quality variables, the results from the SAR model are fully in line with those in Table 8 from the SEM.

An alternative interpretation of the statistical insignificance of tourism variables may rest on the fact that tourists express a different kind of demand for museum attendance: they are perhaps more interested in the collections themselves than in complementary services, so that the tourism flows should not represent a reason for museum to provide more services. Dalle Nogare and Scuderi (2020) even find evidence of a negative effect of an area’s tourism vocation on the probability for museum to host an event, that is a specific type of museum service.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2008) Persistence of power, elites, and institutions. Am Econ Rev 98(1):267–293

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91(5):1369–1401

Acemoglu D, Naid S, Restrepo P, Robinson JA (2019) Democracy does cause growth. J Polit Econ 127(1):47–100

Adomaku S, Ahsan M, Amankwah-Amoah J, Danso A, Kesse K, Frimpong K (2021) Corruption and SME growth: the roles of institutional networking and financial slack. J Inst Econ 17(4):607–624

Alfano MR, Baraldi AR, Cantabene C (2022) Eppur si muove: an evaluation of museum policy reform in Italy. J Cult Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-022-09447-6

Almond G, Verba V (1963) The civic culture: political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Anselin L, Florax RJGM (1995) New directions in spatial econometrics. Springer, Berlin

Baldi S, Vannoni D (2017) The impact of centralization on pharmaceutical procurement prices: the role of institutional quality and corruption. Reg Stud 51(3):426–438

Beretta E, Firpo G, Migliardi A, Scalise D (2019) La valorizzazione del patrimonio artistico e culturale in Italia: confronti internazionali, divari territoriali, problemi e prospettive. Questioni di Economia e Finanza Occasional Paper, Banca d’Italia, p. 524

Bertacchini EE, Dalle NC, Scuderi R (2018) Ownership, organization structure and public service provision: the case of museums. J Cult Econ 42(4):619–643

Cellini R, Cuccia T (2018) How free admittance affects charged visits to museums: an analysis of the Italian case. Oxf Econ Pap 70(3):680–698

Cellini R, Cuccia T, Lisi D (2020) Spatial dependence in museum services: an analysis of the Italian case. J Cult Econ 44(4):535–562

Charron N, Dijkstra L, Lapuente V (2014) Regional governance matters: quality of government within European Union member states. Reg Stud 48(1):68–90

Charron N, Dijkstra L, Lapuente V (2015) Mapping the regional divide in Europe: a measure for assessing quality of government in 206 European regions. Soc Indic Res 122(2):315–346

Corrado L, Fingleton B (2012) Where is the economics in spatial econometrics? J Reg Sci 52(2):210–239

Dal Bó E, Rossi MA (2007) Corruption and inefficiency: theory and evidence from electric utilities. J Public Econ 91(5–6):939–962

Dalle NC, Murzyn-Kupisz M (2021) Do museums foster innovation through engagement with the cultural and creative industries? J Cult Econ 45(4):671–704

Dalle NC, Scuderi R (2020) Branching out beyond the core: museums hosting events. Ann Tour Res 82:1002773

Dalle NC, Scuderi R, Bertacchini E (2021) Immigrants, voter sentiment and local public goods: the case of museums. J Reg Sci 61(5):1087–1112

De Luca G, Lisi D, Martorana M, Siciliani L (2021) Does higher institutional quality improve the appropriateness of healthcare provision? J Public Econ 194:104356

Del Barrio-Tellado MJ, Herrero-Prieto LC (2019) Modelling museum efficiency in producing inter-reliant outputs. J Cult Econ 43(3):485–512

Del Barrio-Tellado MJ, Herrero-Prieto LC (2022) Analysing productivity and technical change in museums: a dynamic network approach. J Cult Econ 53(1):24–34

Di Tella R, Schargrodsky E (2003) The role of wages and auditing during a crackdown on corruption in the city of Buenos Aires. J Law Econ 46(1):269–292

Drukker DM, Egger P, Prucha IR (2013a) On two-step estimation of a spatial autoregressive model with autoregressive disturbances and endogenous regressors. Economet Rev 32(5–6):686–733

Drukker DM, Prucha IR, Raciborski R (2013b) Maximum likelihood and generalized spatial two-stage least squares estimators for a spatial autoregressive model with spatial autoregressive disturbances. Stand Genomic Sci 13(2):221–241

Drukker DM, Prucha IR, Raciborski R (2013c) A command for estimating spatial-autoregressive models with spatial autoregressive disturbances and additional endogenous variables. Stand Genomic Sci 13(2):287–301

Durlauf SN (2018) Institutions, development and growth: where does evidence stand? Economic Development and Institutions Working Paper 18/04.1.

Elhorst JP (2014) Spatial econometrics: from cross-sectional data to spatial panels. Springer, Berlin

Frei BS, Meier S (2006) The economics of museums. In: Ginsburgh VA, Throsby D (eds) Handbook of the economics of art and culture. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1017–1047

Ganau R, Rodriguez-Pose A (2019) Do high-quality local institutions shape labour productivity in Western European manufacturing firms? Pap Reg Sci 98(4):1633–1666

Griffith DA (2006) Assessing spatial dependence in count data: Winsorized and spatial filter specification alternatives to the auto-Poisson model. Geogr Anal 38(2):160–179

Guccio C, Lisi D, Rizzo I (2019) When the purchasing officer looks the other way: on the waste effects of debauched local environment in public works execution. Econ Governance 20(3):205–236

Guccio C, Martorana M, Mazza I, Pignataro G, Rizzo I (2020) An analysis of the managerial performance of Italian museums using a generalised conditional efficiency model. Socioecon Plann Sci 72:100891

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2016) Long-term persistence. J Eur Econ Assoc 14(6):1401–1436

Haggard S, Tiede L (2011) The rule of law and economic growth: where are we? World Dev 39(5):673–685

Halleck Vega S, Elhorst JP (2015) The SLX model. J Reg Sci 55(3):339–363

Huggins R (2016) Capital, institutions and urban growth systems. Camb J Reg Econ Soc 9(2):443–463

ISTAT (2021) Indagine sui musei e le istituzioni similari: Microdati ad uso pubblico. Roma: ISTAT. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/167566. Accessed 27 May 2022

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Matruzzi M (2010) The worldwide governance indicators: a summary of methodology, data and analytical issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430. World Bank, Washington, DC

Kelejian HH, Prucha IR (2010) Specification and estimation of spatial autoregressive models with autoregressive and heteroskedastic disturbances. J Econometr 157(1):53–67

Lasagni A, Nifo A, Vecchione G (2015) Firm productivity and institutional quality: evidence from Italian industry. J Reg Sci 55(5):774–800

Le Sage JP, Pace RK (2009) Introduction to spatial econometrics. Chapman and Hall, New York

Lee LF (2004) Asymptotic distributions of quasi-maximum likelihood estimators for spatial autoregressive models. Econometrica 72(6):1899–1925

Leva L, Menicucci V, Roma G, Ruggeri D (2019) Innovazioni nella governance dei musei statali e gestione del patrimonio culturale: Alcune evidenze da un’indagine della Banca d’Italia. Questioni di Economia e Finanza Occasional Paper, Banca d’Italia, p 525

Lipset SM (1959) Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. Am Polit Sci Rev 53(1):69–105

Manski C (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60(3):531–542

Manski C (2000) Economic analysis of social interactions. J Econ Perspect 14(3):115–136

Moreno-Mendoza HA, Santana-Talavera A, Boza-Chirino J (2020) Perception of governance, value and satisfaction in museums from the point of view of visitors. Preservation-use and management model. J Cult Herit 41(1):178–187

Nannicini T, Stella A, Tabellini G, Troiano U (2013) Social capital and political accountability. Am Econ J Econ Pol 5(2):222–250

Nifo A, Vecchione G (2014) Do institutions play a role in skilled migration? The case of Italy. Region Stud 48(10):1628–1649

Nifo A, Scalera D, Vecchione G (2017) The rule of law and educational choices: evidence from Italian regions. Reg Stud 51(7):1048–1062

North DC (1981) Structure and change in economic history. Norton, New York

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

OECD-ICOM (2019) Culture and local development: maximising the impact: a guide for local governments, communities and museums, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2019/07, Paris: OECD Publishing

Plaza B (2006) The return on investment of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Int J Urban Reg Res 30:452–467

Putnam R, Leonardi R, Nanetti R (1993) Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Rose-Ackerman S (1997) The political economy of corruption. In: Elliott KA (ed) Corruption and the global economy. Institute for International Economics, Washington, pp 31–60

Saaty TL (1980) The analytic hierarchy process. McGraw-Hill, New York

Sequeira S (2012) Advances in measuring corruption in the field. In: Serra D, Wantchekon L (eds) New advances in experimental research on corruption, chapter 6. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, pp 145–175

Tabellini G (2010) Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. J Eur Econ Assoc 8(4):677–716

Voigt S (2013) How (not) to measure institutions. J Inst Econ 9(1):1–26

Wagner GA, Bologna-Pavlik J (2020) Patent intensity and concentration: the effect of institutional quality on MSA patent activity. Pap Reg Sci 99(4):857–898

Wong HL, Wang Y, Luo R, Zhang L, Rozelle S (2017) Local governance and the quality of local infrastructure: evidence from village road projects in rural China. J Public Econ 152:119–132

Yan J, Oum TH (2014) The effect of government corruption on the efficiency of US commercial airports. J Urban Econ 80:119–132

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Catania within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. We acknowledge economic support from PIACERI-2020 (internal university research funding programmes) and from PON-AIM project. This research also contributes to the PNRR GRInS Project (Spoke 8, wp 2). We thank Enrico Bertacchini, Chiara Dalle Nogare, Marco Martorana, and Roberto Patuelli, along with the Editors, Emanuela Marrocu and Alessandro Sapio, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. The responsibility for the content remains on the authors only.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest/competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cellini, R., Cuccia, T., Ferrante, L. et al. The Quality of Regional Institutional Context and Museum Service Provision: Evidence from Italy. Ital Econ J 10, 155–195 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00222-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00222-w