Abstract

There is extensive evidence on waste effects of environmental corruption in public works procurement. However, corruption is not the only source of waste. In this paper, we adopt a wider perspective and look at the environmental institutional quality, identifying the channels through which it can lead to different types of waste in public works execution. We firstly provide some empirical evidence on public works contracts managed by a large sample of Italian municipalities, showing that performance measures of public works execution are associated with the quality of local institutional environment in which they are executed. Motivated by this evidence, we develop a model where weak institutions entail low accountability of purchasing officers, thus they have low incentives to pursue the mandated task of monitoring the execution of contracts, even if no bribery occurs. Then, we assume that endemic environmental corruption increases the return of managerial effort devoted to rent-seeking activities for getting cost overruns, leading the contractor to divert effort from the productive activity. Overall, our model predictions conform well with the empirical evidence on Italian public works execution.

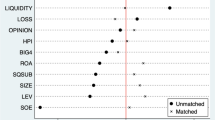

Source: Our elaboration on data provided by Nifo and Vecchione (2014)

Source: Our elaboration on data provided by AVPC and by Nifo and Vecchione (2014). Note In the figure we plot public works performance measures as a function of IQI index at provincial level using a binned scatter plot (using “binscatter” in Stata)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Besides public works procurement, several studies investigate the negative effects of corruption on economic growth (Mauro 1995; Meon and Sekkat 2005), on financial markets (Guiso et al. 2000) and on the accountability of institutions (Hunt 2005) suggesting that corruption represents a major obstacle to economic development. For a survey on the economic analysis of corruption, see among the others e.g., Aidt (2003).

In a similar perspective, Chong et al. (2013) study the relationship between the institutional quality and the use of negotiated procedures in public procurement, showing that the quality of the institutional framework is crucial in order to understand the awarding procedures put in place in the European regions.

Among these, Svensson (2003) and Clarke and Xu (2004) study the characteristics of firms that pay bribes. Dal Bó and Rossi (2007) investigate the connection between corruption and the efficiency of electricity distribution firms. Looking at the strategic role of monitoring, Di Tella and Schargrodsky (2003) analyse the context of hospital procurement, whereas Yan and Oum (2014) investigate the effect of corruption on the efficiency of a sample of commercial airports.

More details on the Italian system of public works are provided in the on-line appendices—Appendix A.

Estimated engineering costs are used as the reserve price in tendering procedures. We use only public works for roads (about a quarter of all works yearly procured) to limit the heterogeneity connected with the characteristics of public work.

The sample composition and time coverage minimize the likelihood of selection bias. In fact, our sample covers the universe of all Italian public works contracts for roads managed by Italian municipalities in the period 2000–2012 and completed by 2014. Thus, in principle, the municipalities which are not represented in the sample are only those that did not communicate the data to the AVCP or did not manage any public work for roads (with estimated engineering costs between 150,000 and 5 million euros) in the time span period or with incomplete records. On the other hand, we cannot completely rule out that these factors are non-systematic at the municipal level. For this reason, some caution is needed in the interpretation of the following empirical findings.

In particular, the IQI index includes 24 elementary indexes grouped into five dimensions, capturing the major characteristics of a governance system: (1) Voice and accountability; (2) Government effectiveness; (3) Regulatory quality; (4) Rule of law; (5) Corruption.

For further details on the construction of the IQI index, see https://sites.google.com/site/institutionalqualityindex.

As baseline estimate, we use 2004 data as it is the first year available and it is quite well centred with respect to the period in which our sample of public work contracts was awarded. In this respect, notice that the choice of the year does not pose crucial problems, since it is reasonable to assume that the processes of institutional change occur slowly and that significant changes in the institutional quality take place only in the medium-long term (Nifo and Vecchione 2014). Nonetheless, in Sect. 2.3 as robustness checks we have also provided estimates with yearly IQI indexes, using the subsample of public works awarded in the period 2004–2012.

As suggested by an anonymous reviewer, the provincial level is more representative of the municipalities’ institutional environment. Nevertheless, in the regression-based evidence we also report in the on-line appendices (Appendix D) the estimates employing the IQI indexes at regional level that, by and large, confirm the main results reported in the text.

To generate a binned scatterplot, binscatter groups the x-axis variable into equal-sized bins, computes the mean of the x-axis and y-axis variables within each bin, then creates a scatterplot of these data points. To estimate the binned scatter plot in Fig. 2, we employ 20 bins using the routine “binscatter” in Stata. See Stepner (2013) for further details.

Overall, both normalized and absolute values of delays and cost overruns are employed in the literature. Normalized values are used, for instance, by Decarolis and Palumbo (2015) in a dataset similar to that employed in this paper. We also performed our empirical exercise using the absolute value of cost overruns and delay with results in line with those reported here. The estimates are available from authors upon request.

For the pairwise correlation matrix, see Table C.1 in the on-line appendices (Appendix C).

For further discussion on these points, see the statistical analysis reported in the Tables C.2 and C.3 in the on-line appendices (Appendix C).

We employ as baseline the year 2004. Later, as robustness checks, we also estimate (1) with the yearly IQI indexes (i.e. from 2004 to 2012), with results fully in line. This is not surprising as changes in the institutional quality occur slowly (Nifo and Vecchione 2014), thus the correlation between IQI indexes in 2004 and in 2012 tends to be very high.

All the variables employed and their descriptive statistics are listed in on-line appendices (Appendix B, Table B.1).

Estimates are available upon request.

We have also tried alternative empirical specifications using OLS and panel Tobit with random effects. The results of these alternative estimates do not qualitatively affect our main findings reported here and are available upon request.

As for the other controls, we find that a higher value of the work PW_VALUE, as well as new public works NEW_PW, are significantly associated with longer delays in the execution. Instead, large municipalities LARGE_MUN seem to be more efficient in ensuring the completion of public works on time. Finally, we do not find any significant effect for the type of procedure NEGOTIATION and the obligation to design the project for the private contractor PROJECT.

We are implicitly assuming that the relevant aspects in the execution of public works are the time and the cost of execution. We are aware that other aspects, such as intrinsic quality of the public work, are important and, thus, this may represent a caveat in our model. However, on this we follow the main literature in public works execution that largely looks at these two commitments to assess the performance in the execution (see Sect. 2).

To some extent, being productive or slacking for an executing firm may have the effect of improving or worsening its reputation in the market and, therefore, this reputation effect should be somewhat considered by a contractor. Indeed, different studies in the literature emphasize the importance of reputation as a device to get more efficient execution of public works (e.g., Doni 2006; Dellarocas et al. 2006; Spagnolo 2012). However, in many countries still the previous performance of a firm does not play a role (e.g., Decarolis et al. 2016). This is the case in the Italian public procurement system, thus our model is consistent with the stylized evidence in Sect. 2, though recently rules are changing.

As argued and throughout assumed in the principal-agent literature, only the final outcome can be observed by the contracting authority, not its composition between the purchasing officer’s monitoring effort and talent.

Accordingly, the outcome is also normally distributed

$$ y \sim N\left( {e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {inputs} \right), \sigma_{\theta }^{2} \left[ {e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {inputs} \right)} \right]^{2} + \sigma_{\varepsilon }^{2} } \right) $$.

In particular, it can be easily shown that the joint density of talent and outcome is the following bivariate normal:

$$ \left( {\theta , y} \right) \sim N\left( { \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} 1 \\ {e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {inputs} \right)} \\ \end{array} } \right) , \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\sigma_{\theta }^{2} } & {e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {inputs} \right)\sigma_{\theta }^{2} } \\ {e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {inputs} \right)\sigma_{\theta }^{2} } & {\sigma_{\theta }^{2} \left[ {e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {inputs} \right)} \right]^{2} + \sigma_{\varepsilon }^{2} } \\ \end{array} } \right) } \right) $$.

Differently from the contracting authority (4), notice that when the purchasing officer chooses the monitoring activity the outcome is still uncertain and, in particular, it is stochastic for the presence of the productivity shock \( \varepsilon \).

The explicit form of the covariance between talent and likelihood ratio clearly depends on the explicit functional forms of the model. However, the strong complementarity between talent and monitoring activity in the specific form of the observable outcome \( \left( {y = \theta e_{m}^{*} \left( a \right) F\left( {\bar{k}, l, m} \right) + \varepsilon } \right) \) suggests that the covariance should exhibit an inverted u-shape respect to the monitoring effort (e.g., Dewatripont et al. 1999b). Furthermore, given that the marginal disutility of monitoring effort is increasing (i.e. \( C^{{\prime \prime }} \left( a \right) > 0 \)), under fairly general and harmless assumption the optimal policy (5) exists and is unique (see the on-line appendices—Appendix E).

Other functional forms, while they lead to more complicated algebra, would not affect the implications of the model as long as they follow the direction of derivates.

Looking at the other comparative statics of (6), they are quite reasonable and intuitive. In particular, a higher dispersion of productivity shock (\( \sigma_{\varepsilon }^{2} \)) decreases the expected benefit of inducing a higher observable outcome and, thus, decreases the optimal monitoring activity (\( a^{*} \)). On the other hand, a higher dispersion of purchasing officer’s talent (\( \sigma_{\theta }^{2} \)) increases the covariance between talent and observable outcome and, thus, the expected benefit of signalling his talent through a higher observable outcome, leading the purchasing officer to increase the monitoring activity (\( a^{*} \)).

As said in footnote 21, a potential limitation of our model is that we focus on the time and the cost of execution. Though on this we largely follow the literature, the intrinsic quality of the work might also be important in public works execution. In a corrupt environment as that studied in our model, for instance, another corruption scheme might be to provide a worse intrinsic quality in the execution of the work (e.g., poor materials), and split the cost savings between the contractor and the purchasing officer. Interestingly, in this case the waste effect of corruption would not give raise to a cost overrun (as the revenue of the contractor would still be that agreed in the contract), but to a worse intrinsic quality of the work. Therefore, a corrupt environment might also give raise to a lower intrinsic quality of the work; in this respect, unfortunately, the quality of public works (e.g., highways) is usually very difficult to measure in the empirical analyses.

Not surprisingly, purchasing officer’s behaviour (i.e. monitoring activity) strictly depends on how the contractor is willing to share the additional revenue. In particular, when the fraction \( \delta \) gets close to 1, then the value of the bribe becomes low and the effect of the rent-seeking activity tends to disappear. On the other hand, when the fraction \( \delta \) gets smaller, then the value of the bribe increases and the effect on the purchasing officer’s behaviour becomes significant.

For example, the construction of a public building to host a public service might be prone to corruption schemes aimed to delay the execution, to pay rents to the private owner of the building temporary hosting the public service.

The calculation of standard costs was required since 1994 (L. 109/1994, art. 4), confirmed in the 2006 Code of public contracts for works, services and supplies (art. 7, c. 4, lett. b), then it has been cancelled by a recent reform but, successively reintroduced (L. 96/2017, art. 213, c. 3, lett. h-bis). Methodological studies had also been provided by the Authority in 2003 and in 2012 but with no practical consequences.

References

Aidt T (2003) Economic analysis of corruption: a survey. Econ J 113:F632–F652

Alesina A, Tabellini G (2007) Bureaucrats or politicians? Part I: a single policy task. Am Econ Rev 97(1):169–179

Alesina A, Tabellini G (2008) Bureaucrat or politicians? Part II: multiple policy tasks. J Public Econ 92:426–447

Alonso R, Matouschek N (2008) Optimal delegation. Rev Econ Stud 75(1):259–293

Ancarani A, Guccio C, Rizzo I (2016) An empirical assessment of the role of firms’ qualification in public contracts execution. J Public Procure 16(4):554–582

Auriol E (2006) Corruption in procurement and public purchase. Int J Ind Organ 24:867–885

Bajari P, Lewis G (2011) Procurement contracting with time incentives: theory and evidence. Q J Econ 126(3):1173–1211

Bajari P, Tadelis S (2006) Incentives and award procedures: competitive tendering vs. negotiations in procurement. In: Dimitri N, Piga G, Spangnolo G (eds) Handbook of procurement. Cambridge University Press, New York

Bajari P, McMillan R, Tadelis S (2009) Auctions versus negotiations in procurement: an empirical analysis. J Law Econ Organ 25(2):372–399

Bajari P, Houghton S, Tadelis S (2014) Bidding for incomplete contracts: an empirical analysis of adaptation costs. Am Econ Rev 104:1288–1319

Baldi S, Bottasso A, Conti M, Piccardo C (2016) To bid or not to bid: that is the question: public procurement, project complexity and corruption. Eur J Polit Econ 43:89–106

Bandiera O, Prat A, Valletti T (2009) Active and passive waste in government spending: evidence from a policy experiment. Am Econ Rev 99:1278–1308

Besley T (2006) Principled agents? The political economy of good government. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Boschma R, Marrocu E, Paci R (2016) Symmetric and asymmetric effects of proximities. The case of M&A deals in Italy. J Econ Geogr 16(2):505–535

Charron N, Dijkstra L, Lapuente V (2014) Regional governance matters: quality of government within European Union member states. Reg Stud 48(1):68–90

Charron N, Dijkstra L, Lapuente V (2015) Mapping the regional divide in Europe: a measure for assessing quality of government in 206 European regions. Soc Indic Res 122(2):315–346

Chong E, Klien M, Saussier S (2013) The quality of governance and the use of negotiated procurement procedures: some (un) surprising evidence from the European Union. Mimeo, New York City

Clarke G, Xu L (2004) Ownership, competition, and corruption: bribe takers versus bribe payers. J Public Econ 88(9–10):2067–2097

Corts KS (2012) The interaction of implicit and explicit contracts in construction and procurement contracting. J Law Econ Organ 28:550–568

Coviello D, Gagliarducci S (2017) Tenure in office and public procurement. Am Econ J Econ Policy 9(3):59–105

Coviello D, Moretti L, Spagnolo G, Valbonesi P (2017) Court efficiency and procurement performance. Scand J Econ 12:3. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12225

Coviello D, Guglielmo A, Spagnolo S (2018) The effect of discretion on procurement performance. Manage Sci 64(2):715–738

Dal Bó E, Rossi MA (2007) Corruption and inefficiency: theory and evidence from electric utilities. J Public Econ 91:939–962

Dastidar KG, Mukherjee D (2014) Corruption in delegated public procurement auctions. Eur J Polit Econ 35:122–127

Decarolis F (2014) Awarding price, contract performance and bids screening: evidence from procurement auctions. Am Econ J Appl Econ 6(1):108–132

Decarolis F, Palumbo G (2015) Renegotiation of public contracts: an empirical analysis. Econ Lett 132:77–81

Decarolis F, Spagnolo S, Pacini R (2016) Past performance and procurement outcomes. NBER working paper, no. 22814

Dellarocas C, Dini F, Spagnolo G (2006) Designing reputation mechanisms. In: Dimitri N, Piga G, Spagnolo G (eds) Handbook of procurement. Cambridge University Press, New York

Dewatripont M, Jewitt I, Tirole J (1999a) The economics of career concerns, part I: comparing information structures. Rev Econ Stud 66:183–198

Dewatripont M, Jewitt I, Tirole J (1999b) The economics of career concerns, part II: applications to missions and accountability of government agencies. Rev Econ Stud 66:199–217

Di Tella R, Schargrodsky E (2003) The role of wages and auditing during a crackdown on corruption in the city of Buenos Aires. J Law Econ 46(1):269–292

Doni N (2006) The importance of reputation in awarding public contracts. Ann Public Coop Econ 4:401–429

Dosi C, Moretto M (2015) Procurement with unenforceable contract time and the law of liquidated damages. J Law Econ Organ 31(1):160–186

Elliott KA (1997) Corruption and the global economy. Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC

Escaleras M, Lin S, Register C (2010) Freedom of information acts and public sector corruption. Public Choice 145:435–460

Finocchiaro Castro M, Guccio C, Rizzo I (2014) An assessment of the waste effects of corruption on infrastructure provision. Int Tax Public Finance 21(4):813–843

Galli E, Rizzo I, Scaglioni C (2017) Transparency, quality of institutions and performance in the Italian municipalities. ISEG working paper no. 11/2017/DE/UECE. Lisbon School of Economics and Management

Ganuza JJ (2007) Competition and cost overruns in public procurement. J Ind Econ 55(4):633–660

Gil R, Marion J (2013) Self-enforcing agreements and relational contracting: evidence from California highway procurement. J Law Econ Organ 29(2):239–277

Golden MA, Picci L (2005) Proposal for a new measure of corruption, illustrated with Italian data. Econ Politics 17(1):37–75

Greene WH (2008) Econometric analysis, 6th edn. Prentice-Hall International, Upper Saddle River

Guccio C, Pignataro G, Rizzo I (2012a) Determinants of adaptation costs in procurement: an empirical estimation on Italian public works contracts. Applied Economics 44(15):1891–1909

Guccio C, Pignataro G, Rizzo I (2012b) Measuring the efficient management of public works contracts: a non-parametric approach. J Public Procure 4:528–546

Guccio C, Pignataro G, Rizzo I (2014) Do local governments do it better? Analysis of time performance in the execution of public works. Eur J Polit Econ 34:237–252

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2000) The role of social capital in financial development. Am Econ Rev 94(3):526–556

Hessami Z (2014) Political corruption, public procurement, and budget composition: theory and evidence from OECD countries. Eur J Polit Econ 34:372–389

Heywood PM, Rose J (2014) “Close but no cigar”: the measurement of corruption. J Public Policy 34(3):1–23

Holmstrom B (1982) Essays in economics and management in honor of Lars Wahlbeck, vol 66. Swedish School of Economics, Helsinki

Holmstrom B, Milgrom P (1991) Multitask principal–agent analyses: incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. J Law Econ Organ 7:24–52

Hunt J (2005) Why are some public officials more corrupt than others? In: Rose-Ackerman S (ed) International handbook on the economics of corruption. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2010) The worldwide governance indicators: a summary of methodology, data and analytical issues. World Bank Policy research working paper no. 5430. World Bank, Washington, DC

Kyriacou AP, Muinelo-Gallo L, Roca-Sagalé O (2015) Construction corrupts: empirical evidence from a panel of 42 countries. Public Choice 165:123–145

Laffont JJ, Martimort D (2001) The theory of incentives: the principal–agent model. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Laffont JJ, Tirole J (1993) A theory of incentives in procurement and regulation. MIT Press, Cambridge

Lasagni A, Nifo A, Vecchione G (2015) Firm productivity and institutional quality. Evidence from Italian industry. J Reg Sci 55(5):774–800

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110:680–712

Meon P, Sekkat K (2005) Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice 122:69–97

Mizoguchi T, Van Quyen N (2014) Corruption in public procurement market. Pac Econ Rev 19(5):577–591

Moretti L, Valbonesi P (2015) Firms’ qualifications and subcontracting in public procurement: an empirical investigation. J Law Econ Organ 31:568–598

Nannicini T, Stella A, Tabellini G, Troiano U (2013) Social capital and political accountability. Am Econ J Econ Policy 5(2):222–250

Nifo A, Vecchione G (2014) Do Institutions play a role in skilled migration? The case of Italy. Reg Stud 48(10):1628–1649

OLAF (2013) Public procurement: costs we pay for corruption. Identifying and reducing corruption in public procurement in the EU, Utrecht. www.pwc.com/euservices. Accessed 2 Aug 2017

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2017) Government at a glance 2017. OECD Publishing, Paris

Persson T, Tabellini G (2000) Political economics: explaining economic policy. MIT Press, Cambridge

Rose-Ackerman S (1999) Corruption and government. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sequeira S (2012) Advances in measuring corruption in the field. In: Serra D, Wantcheko L (eds) New advances in experimental research on corruption, research in experimental economics. Bingley, pp 145–175

Spagnolo G (2012) Reputation, competition, and entry in procurement. Int J Ind Organ 30(3):291–296

Stepner M (2013) BINSCATTER: stata module to generate binned scatterplots. Statistical Software Components, Boston College Department of Economics, Chestnut Hill

Svensson J (2003) Who must pay bribes and how much? Evidence from a cross section of firms. Q J Econ 118(1):207–230

Vadlamannati KC, Cooray A (2016) Do freedom of information laws improve bureaucratic efficiency? An empirical investigation. Oxf Econ Pap 68(4):968–993

Yan J, Oum TH (2014) The effect of government corruption on the efficiency of US commercial airports. J Urban Econ 80:119–132

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Toke Aidt, Arye L. Hillman and Isidoro Mazza for valuable suggestions and discussions. We wish also to thank two anonymous referees for their careful review, and the editor, professor Marko Koethenbuerger, for his helpful advices. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guccio, C., Lisi, D. & Rizzo, I. When the purchasing officer looks the other way: on the waste effects of debauched local environment in public works execution. Econ Gov 20, 205–236 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-019-00223-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-019-00223-5