Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to describe the long-term efficacy and safety of upadacitinib and adalimumab through 228 weeks following immediate switch to the alternate therapy with a different mechanism of action (MoA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) not achieving treatment goals with their initial randomized therapy in the ongoing phase 3 SELECT-COMPARE study.

Methods

Patients with non-response or incomplete response to initially prescribed upadacitinib 15 mg once daily or adalimumab 40 mg every other week were switched to the alternate therapy by week 26. Efficacy was evaluated through 228 weeks post-switch using validated outcome measures, including Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) low disease activity (LDA; ≤ 10)/remission (≤ 2.8); 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein ≤ 3.2/< 2.6; ≥ 20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria; and change from baseline in ACR core components. Data are reported as observed. Safety was assessed by treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) through week 264.

Results

Of patients initially randomized to upadacitinib and adalimumab, 38.7% and 48.6%, respectively, switched to the alternate therapy by week 26. Clinically relevant improvements in all efficacy measures were observed through 228 weeks post-switch and were generally similar between groups, with small numeric differences mostly in favor of switching to upadacitinib. CDAI remission was achieved by 32.7% and 28.6% of initial non-responders, and 27.5% and 27.3% of incomplete responders, while CDAI LDA was achieved by 76.9% and 72.9% of non-responders, and 72.5% and 72.7% of incomplete responders switching to upadacitinib and to adalimumab, respectively. TEAE rates were similar between groups, although herpes zoster infection, lymphopenia, and creatine phosphokinase elevation were more frequent when switching to upadacitinib. No new safety signals were identified.

Conclusion

Switching to a different MoA may provide long-term benefit to patients with RA not achieving treatment goals with their initial therapy, with acceptable safety profiles.

Trial Registration

NCT02629159.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Current treatment guidelines support a treat-to-target strategy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with therapy adjustment if no improvement is seen within 3 months, or if treatment targets are not met by 6 months. |

The American College of Rheumatology recommends switching to a drug with a different mechanism of action (MoA) as opposed to switching to one with the same MoA, while the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology recommends both switching to either a different drug of the same class or to a drug with a different MoA as reasonable. |

The present study aimed to describe the long-term efficacy and safety of a bidirectional, immediate switch between a Janus kinase inhibitor (upadacitinib) and a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (adalimumab) in patients with RA who were non-responders or incomplete responders to their initial randomized therapy. |

What was learned from the study? |

Improvements across disease activity measures and functional outcomes were observed through 228 weeks in both switch groups, with numeric differences mostly in favor of patients who switched from adalimumab to upadacitinib; no new safety signals were identified in either group through 264 weeks. |

Switching treatment appears to be beneficial for patients with RA who do not initially meet their treatment goals, and this benefit can be maintained long-term; further research is required to determine whether switching to a drug with a different MoA is superior to switching to a different drug with a similar MoA. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disease that primarily affects the joints, can be associated with significant disability, pain, and reduced quality of life [1]. The current treatment paradigm for RA includes the use of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) [2]. Methotrexate (MTX) is the most widely used csDMARD for first-line treatment of RA.

Clinical remission is widely accepted as the main therapeutic target in RA, with low disease activity (LDA) as a viable alternative in patients who are unable to achieve remission. As a result of the complexity of the disease, patients with RA may require multiple trials of medications with different mechanisms of action (MoAs) to achieve their treatment goal [3,4,5,6]. However, despite the number of currently approved advanced therapies with different MoAs available for patients with RA, including bDMARDs, multiple clinical trials and post-marketing reports [2, 7,8,9,10] have shown that a minority of patients achieve remission or LDA when assessed using the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) or the Simplified Disease Activity Index, metrics favored by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) for assessing disease activity in RA [3, 11, 12].

The EULAR guidance [4] and ACR recommendations [13] for the treatment of RA both support utilizing a treat-to-target (T2T) strategy, and that treatment decisions should be regularly re-evaluated on the basis of the efficacy and tolerability of the initially selected DMARD. In patients with active disease, monitoring should be frequent (every 1–3 months), and therapy should be adjusted if there is no improvement by 3 months after treatment initiation, or if the target has not been reached by 6 months [4]. ACR and EULAR both recommend that, if the initial csDMARD (or combination of csDMARDs) does not achieve the desired treatment goal, an advanced therapy should then be added to the csDMARD. The ACR recommends the initial addition of a bDMARD, such as a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, while EULAR suggests the addition of a bDMARD or tsDMARD, such as a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, after careful consideration of the patient’s risk factors/comorbidities. If the treatment goal is still not achieved, switching to a different drug of the same class, or to a drug with a different MoA, can be considered. EULAR suggests that both these approaches are reasonable, while the ACR guidelines recommend switching to a drug with a different MoA as opposed to switching to one with the same MoA [13].

Data from multiple randomized controlled trials have shown that JAK inhibitors may be efficacious in patients with active RA despite use of a bDMARD, with an acceptable safety profile [7, 14,15,16]. However, data on the safety of an immediate (i.e., without a washout period) switch from a TNF inhibitor to a JAK inhibitor are limited, as is evidence on the efficacy and safety of switching patients to a TNF inhibitor following insufficient response to a JAK inhibitor [17].

Upadacitinib, an oral, reversible JAK inhibitor, has been studied in RA and across patient populations with exposure to different prior therapies [2, 7, 9, 18,19,20,21]. SELECT-COMPARE is an ongoing phase 3 trial investigating upadacitinib 15 mg once daily (QD) versus adalimumab, a TNF inhibitor, 40 mg every other week (EOW), both with concomitant MTX, in patients with RA and inadequate response to MTX [20]. Patients who did not achieve a specified clinical response during the first 26 weeks of the study were switched in a blinded manner from upadacitinib to adalimumab or vice versa, with numerous patients showing substantial benefit in clinical and functional outcomes at 6 and 12 months after switching to the alternate therapy, while no new safety signals were identified [17, 22, 23].

The goal of treatment is to achieve and maintain clinical remission/LDA to prevent long-term damage associated with active or inadequately controlled disease. However, long-term data on the safety and efficacy of the bidirectional, immediate switch between a JAK inhibitor and a TNF inhibitor are currently lacking. The aim of the present study was to describe the long-term efficacy and safety of upadacitinib and adalimumab through week 228 following immediate switch to the alternate therapy in a refractory population of patients with RA who were non-responders (not achieving ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in tender joint count based on 68 joints [TJC68] and swollen joint count based on 66 joints [SJC66] by week 26) or incomplete responders (not achieving CDAI ≤ 10 by week 26) to their initial randomized therapy.

Methods

The study design and eligibility criteria have been described previously [20, 22]. Briefly, SELECT-COMPARE is an ongoing phase 3 randomized study. The first 26 weeks were double-blind, placebo-controlled, and followed by an active comparator-only, double-blind period up to week 48. Patients who completed 48 weeks of treatment could enter an open-label long-term extension (LTE) for up to 10 years on upadacitinib 15 mg QD or adalimumab 40 mg EOW. Eligible patients were ≥ 18 years of age with active RA (≥ 6 swollen joints [of 66 examined] and ≥ 6 tender joints [of 68 examined], high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP] ≥ 5 mg/L, and evidence of erosive disease and/or seropositivity for rheumatoid factor or anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies), on a stable dose of MTX (15–25 mg/week for ≥ 4 weeks prior to the first dose of study drug or ≥ 10 mg/week if intolerant to ≥ 12.5 mg/week) for ≥ 3 months. Patients with inadequate response to a prior bDMARD, or prior exposure to a JAK inhibitor or adalimumab, were excluded.

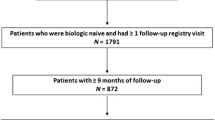

Patients were randomized 2:2:1 to receive upadacitinib 15 mg QD, placebo, or adalimumab 40 mg EOW while remaining on background MTX, and they could also continue oral glucocorticoids (GCs). Patients could be blindly switched within the first 26 weeks from placebo to upadacitinib, upadacitinib to adalimumab, or adalimumab to upadacitinib if one of two switch criteria were met (Fig. 1). Patients who did not achieve ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in TJC68 and SJC66 (non-responders) were switched at weeks 14, 18, or 22. Patients who did not achieve CDAI ≤ 10 (incomplete responders) were switched at week 26. Patients still on placebo at week 26 were switched to upadacitinib. Switch was immediate (without washout): upadacitinib was administered 2 weeks after the last dose of adalimumab, and adalimumab was administered 1 day after the last dose of upadacitinib. Only one treatment switch was permitted per patient. From week 48 onwards, modification or initiation of csDMARDs and oral GCs was allowed at the investigator’s discretion (csDMARD use was restricted to up to two of the following: MTX, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, or leflunomide; the combination of MTX and leflunomide was not permitted) [24, data on file].

Patient disposition and reasons for study drug discontinuation by treatment sequence. Patients who discontinued the study drug are counted under each reason given for discontinuation, and thus the sum of the counts given for the reasons may be greater than the overall number of discontinuations. ADA adalimumab, AE adverse event, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, DC discontinued, EOW every other week, f/u follow-up, inf infection, IR incomplete responders (patients who switched at week 26), l/c logistical restrictions, LoE lack of efficacy, LTE long-term extension, MTX methotrexate, NR non-responders (patients who switched at week 14, 18, or 22), PBO placebo, QD once daily, UPA upadacitinib. aNo rescue was allowed after week 26. bAll patients on PBO not previously rescued (at weeks 14, 18, or 22) were switched to upadacitinib at week 26

The study is being conducted according to the International Council for Harmonization guidelines, local regulations and guidelines governing clinical study conduct, and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study protocol and consent forms were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site. Approval was received from the master ethics committee, the Advarra Institutional Review Board (Pro00034396).

Assessments

Efficacy was evaluated up to week 228 post-switch using validated outcome measures including CDAI LDA and remission (defined as ≤ 10 and ≤ 2.8, respectively); 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28[CRP]) ≤ 3.2 and < 2.6; ≥ 20%/50%/70% improvement in ACR response criteria (ACR20/50/70); and percentage change from baseline in ACR core components, including physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index [HAQ-DI]), disease activity (Patient’s Global Assessment of disease activity [PtGA]; 0–100 mm visual analog scale [VAS], and Physician’s Global Assessment of disease activity [PhGA]; 0–100 mm VAS), patient’s assessment of pain (PtPain; 0–100 mm VAS), markers of inflammation (hsCRP; mg/L), and affected joint counts (TJC68 and SJC66). Response criteria and change from baseline to week 228 post-switch were evaluated as change from original baseline value at randomization.

Safety was assessed up to week 264. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were summarized in patients who had switched to the alternate therapy by week 26. Safety assessments were performed as have been described previously, and TEAEs were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 25.0 [17, 20, 24, 25]. TEAEs are presented as exposure-adjusted event rates (EAERs; events per 100 patient-years [E/100 PY]).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis is descriptive, and data are reported as observed with no imputation for missing data. As switch groups were not randomized for this subset of patients, no direct statistical comparison was made between groups. The efficacy data are presented descriptively, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for safety are based on the exact method for the Poisson mean.

Results

Of the patients initially randomized to upadacitinib 15 mg QD (n = 651) and adalimumab 40 mg EOW (n = 327), a total of 252 (38.7%) and 159 (48.6%) patients, respectively, were switched to the alternate therapy prior to week 26 (non-responders) or at week 26 (incomplete responders). Within each switch group, similar proportions of patients (approximately half) were switched as a result of either non-response or incomplete response [22]. Of the 252 patients who switched to adalimumab, and the 159 who switched to upadacitinib, 228 and 141 entered the LTE, and 140 and 101 completed week 228 post-switch, respectively (Fig. 1). Within the upadacitinib to adalimumab switch group, 37.3% of non-responders and 39.8% of incomplete responders discontinued treatment, while within the adalimumab to upadacitinib switch group, 22.7% of non-responders and 33.3% of incomplete responders discontinued treatment before week 228 post-switch. The most common reasons for discontinuation in both switch groups and in both non-responders and incomplete responders were adverse events (AEs; 9.1% and 11.0%; and 7.6% and 17.3%, respectively) and withdrawal of consent (8.2% and 13.6%; and 4.5% and 5.3%, respectively). Loss of efficacy was the reason for treatment discontinuation in 2.7% and 4.2% of non-responders and incomplete responders who switched to adalimumab, and in 3.0% and 0% of non-responders and incomplete responders who switched to upadacitinib (Fig. 1). Of patients who switched to adalimumab and those who switched to upadacitinib with concomitant oral GC use at baseline, 68.6% (96/140) and 63.5% (61/96), respectively, did not change their dose through week 264. Of the remaining patients, 9.3% and 16.7% decreased, 10.0% and 12.5% increased, and 14.3% and 11.5% stopped GCs at least once, respectively.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics have been reported previously [22]. Briefly, in both switch groups and in non-responders and incomplete responders, 81.7–85.7% of the patients were female, the mean age was 53.3–55.0 years, and the mean disease duration at baseline was 6.4–10.0 years.

Efficacy

Non-responders to Initial Therapy

Among patients who were non-responders to their initial therapy, 76.9% (40/52) of patients who switched to upadacitinib achieved CDAI LDA at week 228 compared with 72.9% (51/70) of those who switched to adalimumab. Of patients who switched to upadacitinib, 32.7% (17/52) achieved CDAI remission at week 228 post-switch compared with 28.6% (20/70) of those who switched to adalimumab (Fig. 2). In addition, 58.0% (29/50) of patients who switched to upadacitinib achieved DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 compared with 50.0% (35/70) of those who switched to adalimumab, and similar proportions of patients who switched to upadacitinib and to adalimumab achieved DAS28(CRP) ≤ 3.2 (76.0% [38/50] and 74.3% [52/70], respectively) at week 228 post-switch (Fig. 3).

Proportions of patients who were non-responders or incomplete responders to the initial therapy and switched to the alternate therapy by week 26, who achieved a CDAI LDA and b CDAI remission through 228 weeks post-switch (as observed). Groups are by treatment sequence as observed, without imputation for missing data. ADA adalimumab, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, LDA low disease activity, UPA upadacitinib

Proportions of patients who were non-responders or incomplete responders to the initial therapy and switched to the alternate therapy by week 26, who achieved a DAS28(CRP) ≤ 3.2 and b DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 through 228 weeks post-switch (as observed). Groups are by treatment sequence as observed, without imputation for missing data. ADA adalimumab, DAS28(CRP) 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on C-reactive protein, UPA upadacitinib

At week 228 post-switch, ACR20 was achieved by 90.4% of patients who switched to upadacitinib compared with 80.6% of those who switched to adalimumab, and ACR50 was achieved by 64.7% of patients who switched to upadacitinib compared with 59.2% of those who switched to adalimumab; ACR70 was achieved by similar proportions of patients who switched to upadacitinib and to adalimumab (44.2% and 42.3%, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Proportions of patients who were non-responders or incomplete responders to the initial therapy and switched to the alternate therapy by week 26, who achieved a ACR20, b ACR50, and c ACR70 through 228 weeks post-switch (as observed). Groups are by treatment sequence as observed, without imputation for missing data. ACR20/50/70 ≥ 20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria, ADA adalimumab, UPA upadacitinib

Improvements in most ACR core components were observed at week 228 post-switch in both switch groups (adalimumab to upadacitinib and upadacitinib to adalimumab), with the exception of hsCRP in the upadacitinib to adalimumab group. The mean percentage change from baseline through 228 weeks post-switch in ACR core components for these two groups, respectively, was as follows: HAQ-DI (− 42.7% and − 35.8%), PtGA (− 55.0% and − 48.1%), PhGA (− 82.1% and − 70.7%), PtPain (− 55.1% and − 48.2%), hsCRP (− 50.5% and + 22.6%), TJC68 (− 84.3% and − 86.8%), and SJC66 (− 93.0% and − 88.5%) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Of note, the positive mean value for hsCRP in the upadacitinib to adalimumab switch group was due to extreme observations at week 228 post-switch. The median percentage change from baseline for hsCRP in this subgroup was − 55.1% (data not shown).

Incomplete Responders to Initial Therapy

Among patients who were incomplete responders to their initial therapy, similar proportions of patients who switched to upadacitinib and to adalimumab achieved CDAI LDA (72.5% [37/51] and 72.7% [48/66], respectively) and CDAI remission (27.5% [14/51] and 27.3% [18/66], respectively) at week 228 post-switch (Fig. 2). Similar proportions of patients who switched to upadacitinib and to adalimumab achieved DAS28(CRP) ≤ 3.2 (73.3% [33/45] and 72.1% [44/61], respectively), while 48.9% (22/45) of patients who switched to upadacitinib achieved DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 compared with 52.5% (32/61) of those who switched to adalimumab (Fig. 3).

At week 228 post-switch, ACR20 and ACR50 were achieved by similar proportions of patients who switched to upadacitinib compared with those who switched to adalimumab (89.6% vs. 92.4%, and 70.8% vs. 73.8%, respectively), while ACR70 was achieved by 50.0% of patients who switched to upadacitinib and by 40.3% of those who switched to adalimumab (Fig. 4).

Improvements in all ACR core components were observed at week 228 post-switch in both switch groups (adalimumab to upadacitinib and upadacitinib to adalimumab). The mean percentage change from baseline through 228 weeks post-switch in ACR core components for these two groups, respectively, was as follows: HAQ-DI (− 38.2% and − 42.9%), PtGA (− 57.7% and − 58.7%), PhGA (− 82.0% and − 81.1%), PtPain (− 56.0% and − 60.6%), hsCRP (− 43.2% and − 42.0%), TJC68 (− 89.7% and − 89.5%), and SJC66 (− 93.1% and − 93.6%) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Safety

The overall exposure-adjusted TEAE rate at week 264 was lower among patients who switched to upadacitinib compared with those who switched to adalimumab (165.0 [95% CI: 154.6, 175.9] vs. 205.7 [196.0, 215.7] E/100 PY). The most frequent AE in both groups was infection (56.7 [50.7, 63.3] and 62.7 [57.4, 68.3] E/100 PY in patients who switched to upadacitinib and in those who switched to adalimumab, respectively). The rate of herpes zoster infection was 3.2 (1.9, 5.0) E/100 PY among patients who switched to upadacitinib and 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) E/100 PY among those who switched to adalimumab, while the rate of serious infection was 4.8 (3.1, 6.9) E/100 PY among patients who switched to upadacitinib and 2.9 (1.9, 4.3) E/100 PY among those who switched to adalimumab. The rates of lymphopenia and creatine phosphokinase (CPK) elevation were 1.8 (0.8, 3.2) and 2.5 (1.3, 4.1) E/100 PY, respectively, among patients who switched to upadacitinib, compared with 0.6 (0.2, 1.4) and 1.9 (1.1, 3.1) E/100 PY, respectively, among those who switched to adalimumab. Two cases of active tuberculosis were reported in the group that switched to adalimumab (0.2 [0.0, 0.9] E/100 PY); no cases of tuberculosis were reported in the group that switched to upadacitinib. The TEAE rates for most other AEs, including AEs leading to discontinuation, malignancies, major adverse cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolic events, and deaths, were largely similar between the two switch groups (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

The recommendations from EULAR and ACR (particularly the ACR guidelines) have highlighted that switching MoA in the event of insufficient response to the initial treatment is more logical than switching to a molecule with the same MoA, in an effort to reach patients’ treatment goals [3, 4, 13]. Yet, long-term data on the efficacy and safety of switching therapy in a treatment-refractory population within a clinical trial setting is limited. The aim of the present study was to investigate the long-term efficacy and safety of upadacitinib and adalimumab through 228 weeks following switch to the alternate therapy in patients with RA who were non-responders or incomplete responders to the initial randomized therapy. The results were similar to those observed at 6 months [22], with improvements in disease activity measures and functional outcomes in both switch groups (adalimumab to upadacitinib and upadacitinib to adalimumab) through 228 weeks post-switch. The data reported here strongly suggest that there is a long-term benefit associated with switching therapy for patients with RA not meeting treatment goals with their initially allocated treatment.

Clinically relevant improvements across disease activity measures were observed after switching in both the upadacitinib and adalimumab groups, and in both initial non-responders and incomplete responders within each switch group. These improvements were generally similar in both groups, while small numeric differences observed between switch groups were mostly in favor of patients switching from adalimumab to upadacitinib for the majority of outcome measures across timepoints, particularly among initial non-responders. Improvements from baseline were also observed in functional and patient-reported outcomes in both switch groups, and in both non-responders and incomplete responders. As observed for disease activity measures, these improvements were also largely similar between groups, although small numeric differences were mostly in favor of non-responders in both switch groups, and in favor of patients who switched from adalimumab to upadacitinib across timepoints. In addition, numerically greater proportions of patients who switched from adalimumab to upadacitinib completed treatment through week 228 post-switch (77.3% [51/66] of non-responders and 66.7% [50/75] of incomplete responders) compared with those who switched from upadacitinib to adalimumab (62.7% [69/110] of non-responders and 60.2% [71/118] of incomplete responders). Although radiographic progression (change from baseline > 0 in modified Total Sharp Score) was not analyzed in this manuscript, 5-year data from SELECT-COMPARE show that, in patients who switched from adalimumab to upadacitinib and vice versa after achieving no response or an incomplete response to the initial therapy, the proportion of patients with radiographic progression remained low at week 192 [data on file].

No new safety signals were identified through 5 years of treatment. Infection was the most frequent AE in both groups, with herpes zoster infection observed more frequently among patients who switched to upadacitinib. The rate of serious infection was also numerically higher in the group that switched from adalimumab to upadacitinib, and was also slightly higher than has been previously reported for upadacitinib in RA (3.4 and 2.8 E/100 PY including and excluding COVID-19, respectively) [26]; however, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn because of the relatively small number of patients. In the long-term safety analysis of upadacitinib across indications, there were 3209 patients exposed to upadacitinib and 579 patients exposed to adalimumab in the RA cohort [26]. These numbers are considerably larger than the 159 patients switching from adalimumab to upadacitinib and 252 patients switching from upadacitinib to adalimumab in the current analysis. In addition, the rate of serious infections reported in the group who switched from upadacitinib to adalimumab reported here (2.9 E/100 PY) was numerically lower than previously reported for adalimumab in RA (3.5 E/100 PY including COVID-19) [26]. The rates of serious infection reported in the long-term analysis of upadacitinib across indications were similar between upadacitinib and adalimumab (3.4 vs. 3.5 E/100 PY), and these rates were relatively stable over time [26]. These similar rates between upadacitinib and adalimumab suggest that the absence of washout did not appreciably impact the rates of serious infection following treatment switch. Lymphopenia and CPK elevation (transient elevation that did not lead to treatment discontinuation in the majority of patients) were also observed more frequently among patients who switched to upadacitinib. Overall, the safety profile in this population was consistent with the known safety profiles of upadacitinib and adalimumab across indications [26, 27].

In addition to the benefits of switching treatment for patients who do not achieve their treatment goals, a previously reported network meta-analysis, including nine randomized controlled trials and 16 observational studies, suggested that switching from a first-line TNF inhibitor to a drug with a different MoA (e.g., bDMARD or tsDMARD) after treatment failure is more effective [28]. However, the results of a meta-analysis can only be considered as hypothesis-generating and must be confirmed in a well-conducted trial. The results of the present trial support the hypothesis that switching MoA from a primary TNF inhibitor to a tsDMARD, and also from a tsDMARD to a TNF inhibitor, is effective following failure of the initial therapy. In addition, patients switching from adalimumab to upadacitinib had lower discontinuation rates than those switching from upadacitinib to adalimumab in the present study. However, as the study design did not include in-class switch arms, conclusions cannot be drawn on whether an MoA switch is superior to an in-class switch in terms of efficacy and withdrawal rates.

Use of a JAK inhibitor following incomplete response or failure to adalimumab was previously reported to be beneficial in a proportion of patients [7, 29]. To the best of our knowledge, however, SELECT-COMPARE is the first study to report clinical outcomes in patients switching to a TNF inhibitor after insufficient response to a JAK inhibitor, as well as a bidirectional immediate switch between a JAK inhibitor and a TNF inhibitor, with outcomes reported up to 5 years.

Limitations of this study include the fact that the results are observational, and the analysis was not powered for statistical comparisons between switch groups, or between non-responders and incomplete responders. Furthermore, the generalizability of results from a clinical trial population to patients in clinical practice should be approached with caution, as adjusting therapy in accordance with the physician’s clinical judgment may be more typical of a T2T strategy in a real-world setting, while rescue in the context of a clinical trial is performed according to prespecified criteria and at specific timepoints. In addition, analysis of treatment response did not take into consideration how modifications to background RA medications may have contributed to the ability of these patients to achieve treatment goals. Specifically, no analysis was conducted to assess whether a higher proportion of patients who switched to adalimumab also discontinued MTX, which could have affected efficacy in the upadacitinib to adalimumab switch arm. Further well-designed, prospective, properly powered studies (such as the ongoing phase 3b/4 SELECT-SWITCH study [NCT05814627]) are needed to confirm these results, and to establish whether switching to a different MoA is superior to selecting a different drug with a similar MoA in patients with prior failure or insufficient response to their initial RA treatment.

Conclusion

Disease activity measures and functional outcomes were improved in patients initially randomized to upadacitinib or adalimumab following rescue by switching to the alternate therapy in patients with an inadequate response to the initial MoA. These improvements were observed through 228 weeks post-switch, and were mostly in favor of patients who were switched from adalimumab to upadacitinib compared with those observed in the upadacitinib to adalimumab group for efficacy and patient-reported outcome endpoints. No new safety signals were identified in either switch group. These results suggest that a refractory population of patients with RA who do not initially meet their treatment goals may benefit from switching treatment using the T2T approach, and this benefit may be maintained long-term for the majority of patients.

Data Availability

The datasets supporting this study are available upon reasonable request. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis datasets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), provided the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan, and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the US and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://protect-eu.mimecast.com/s/3EcNC026RUgzQoEMswk1XL?domain=abbvieclinicaltrials.com, https://www.abbvieclinicaltrials.com/hcp/data-sharing.

References

Tanaka Y. A review of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2020;30:779–87.

van Vollenhoven R, Takeuchi T, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with moderately-to-severely active rheumatoid arthritis (SELECT-EARLY): a multicenter, multi-country, randomized, double-blind, active comparator-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:1607–20.

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:685–99.

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bergstra SA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:3–18.

Wang Z, Huang J, Xie D, He D, Lu A, Liang C. Toward overcoming treatment failure in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:755844.

Messelink MA, den Broeder AA, Marinelli FE, et al. What is the best target in a treat-to-target strategy in rheumatoid arthritis? Results from a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. RMD Open. 2023;9(2):e003196.

Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Combe B, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-BEYOND): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2513–24.

Smolen JS, Pangan AL, Emery P, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate (SELECT-MONOTHERAPY): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393:2303–11.

Rubbert-Roth A, Enejosa J, Pangan AL, et al. Trial of upadacitinib or abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1511–21.

Kerschbaumer A, Sepriano A, Smolen JS, et al. Efficacy of pharmacological treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature research informing the 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:744–59.

Bykerk VP, Massarotti EM. The new ACR/EULAR remission criteria: rationale for developing new criteria for remission. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(Suppl 6):vi16-20.

England BR, Tiong BK, Bergman MJ, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology recommended rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71:1540–55.

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:924–39.

Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:451–60.

Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1243–52.

Genovese MC, Kalunian K, Gottenberg JE, et al. Effect of filgotinib vs placebo on clinical response in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis refractory to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy: the FINCH 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:315–25.

Fleischmann RM, Genovese MC, Enejosa JV, et al. Safety and effectiveness of upadacitinib or adalimumab plus methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over 48 weeks with switch to alternate therapy in patients with insufficient response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1454–62.

Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the SELECT phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:304–11.

Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2503–12.

Fleischmann R, Pangan AL, Song IH, et al. Upadacitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1788–800.

Parmentier JM, Voss J, Graff C, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the JAK1 selectivity of upadacitinib (ABT-494). BMC Rheumatol. 2018;2:23.

Fleischmann RM, Blanco R, Hall S, et al. Switching between Janus kinase inhibitor upadacitinib and adalimumab following insufficient response: efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:432–9.

Mysler E, Tanaka Y, Kavanaugh A, et al. Impact of initial therapy with upadacitinib or adalimumab on achievement of 48-week treatment goals in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: post hoc analysis of SELECT-COMPARE. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62:1804–13.

Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Bessette L, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results through 3 years from the SELECT-COMPARE study. RMD Open. 2022;8(1):e002012.

Woodworth T, Furst DE, Alten R, et al. Standardizing assessment and reporting of adverse effects in rheumatology clinical trials II: the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria v.2.0. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1401–14.

Burmester GR, Cohen SB, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib over 15,000 patient-years across rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and atopic dermatitis. RMD Open. 2023;9(1):e002735.

Burmester GR, Gordon KB, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Long-term safety of adalimumab in 29,967 adult patients from global clinical trials across multiple indications: an updated analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37:364–80.

Migliore A, Pompilio G, Integlia D, Zhuo J, Alemao E. Cycling of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors versus switching to different mechanism of action therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720x211002682.

Tanaka Y, Fautrel B, Keystone EC, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients switched from adalimumab to baricitinib due to non-response and/or study design: phase III data in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:890–8.

Acknowledgements

AbbVie and the authors thank the participants, study sites, and investigators who are participating in this clinical trial.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance.

Medical writing support was provided by Katerina Betsista, MD, of 2 the Nth (Cheshire, UK), and was funded by AbbVie.

Funding

AbbVie are funding this trial and participated in the trial design, research, analysis, data collection, interpretation of data, and the review and approval of the publication. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this publication. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. All publication fees, including the Rapid Service Fee, were funded by AbbVie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Roy Fleischmann contributed to study conception and design. Roy Fleischmann, Ricardo Blanco, Louis Bessette, Eduardo Mysler, and Filip Van den Bosch participated in the acquisition of patient data. Roy Fleischmann, Ricardo Blanco, Filip Van den Bosch, Louis Bessette, Yanna Song, Sara K. Penn, Erin McDearmon-Blondell, Nasser Khan, Kelly Chan, and Eduardo Mysler contributed to the analysis and interpretation of patient data. All the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All the authors provided final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Roy Fleischmann has received consulting fees and/or grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, BI, Biosplice, BMS, DREN Bio, Flexion, Galapagos, Galvani, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Horizon, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Selecta, Teva, UCB, Viela, Vorso, and Vyne. Ricardo Blanco has received grant/research support from AbbVie, MSD, and Roche; and consulting fees/participated in speaker’s bureau from AbbVie, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Filip Van den Bosch has received speaker and/or consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, and UCB. Louis Bessette has received speaking fees, consulting fees, and grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Lilly, Fresenius Kabi, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, and UCB. Yanna Song, Sara K. Penn, Erin McDearmon-Blondell, Nasser Khan, and Kelly Chan are employees of AbbVie and may hold stock or options. Eduardo Mysler has received speaking fees, consulting fees, and grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Hi-Bio, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, and Sanofi.

Ethical Approval

This study is being conducted according to the International Council for Harmonization guidelines, local regulations and guidelines governing clinical study conduct, and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study protocol and consent forms were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site. Approval was received from the master ethics committee, the Advarra Institutional Review Board (Pro00034396).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fleischmann, R., Blanco, R., Van den Bosch, F. et al. Long-term Efficacy and Safety Following Switch Between Upadacitinib and Adalimumab in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: 5-Year Data from SELECT-COMPARE. Rheumatol Ther 11, 599–615 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00658-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00658-1