Abstract

Introduction

This observational study evaluated response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who switched from an interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor (IL-6Ri) to a Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi) and vice versa.

Methods

Adult patients with RA, who initiated IL-6Ri or JAKi (following discontinuation of JAKi or IL-6Ri, respectively) during/after December 2012 and had a 6-month follow-up visit were enrolled. Clinical outcomes were evaluated at baseline and the follow-up visit. Continuous outcomes included Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), pain, fatigue, tender joint count, swollen joint count, Physician Global Assessment (MDGA), Patient Global Assessment (PtGA), and morning stiffness duration. Categorical outcomes included the proportion of patients achieving CDAI low disease activity (LDA), remission, and minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) for HAQ, pain, fatigue, MDGA, and PtGA. Continuous outcomes were summarized as mean changes from baseline, and categorical outcomes as response rates. Differences in the outcome measures between groups were evaluated using linear and logistic regression models.

Results

Between IL-6Ri (n = 100) and JAKi initiators (n = 129), no significant differences were noted for continuous outcomes. Within both groups, a significant proportion of patients achieved LDA, remission, and MCIDs for other measures, although the odds of achieving LDA were higher among IL-6Ri (vs. JAKi) initiators with moderate-to-severe disease (adjusted odds ratio: 3.30 [1.01, 10.78]).

Conclusions

Patients with RA can achieve improvement in response when switching between IL-6Ri and JAKi. Although both therapies affect the IL-6 pathway, there are distinct mechanisms of action, which likely contribute to their clinical improvement, when reciprocally switched as follow-on treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), clinical practice guidelines recommend switching from a biologic (b) or targeted synthetic (ts) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) to another b/tsDMARD with an alternative mechanism of action (without preference to any class) in case the treatment target is not achieved. |

Although data exist for the effect on clinical outcomes while switching from a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) to another b/tsDMARD, there is limited research on switching between an interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor (IL-6Ri) and a Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), given both classes act on the IL-6 pathway. |

What was learned from this study? |

This observational study showed improvement in clinical outcomes when switching patients with RA from an IL-6Ri to a JAKi (and vice versa), and the responses were generally comparable between the two groups, indicating that the healthcare providers may consider such switch, without concerns that commonalities in their mode of action may hamper clinical effectiveness. |

This is the first study to measure clinical outcomes when switching from an IL-6Ri to a JAKi and from a JAKi to an IL-6Ri in the same patient population and suggests that the distinct mechanisms of action of the two classes account for the observed clinical responses. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease, characterized by synovial inflammation in multiple joints, leading to progressive and irreversible joint damage. If appropriate treatment is not provided, RA can cause significant pain and swelling in the hands and feet, loss of physical function, and a deterioration in the overall quality of life [1, 2].

Conventional synthetic (cs) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have been in use for decades in RA treatment [1]. However, in the last 20 years, significant advances have been made in the treatment landscape with the advent of other DMARDs. Various biologic (b) and targeted synthetic (ts) DMARDs (b/tsDMARDs) are now available as treatment options for RA, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), interleukin-6 receptor inhibitors (IL-6Ri), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4-immunoglobulin (CTLA4-Ig), anti-CD20, and Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

Despite these advances, many patients fail to achieve or sustain the treatment target (i.e., low disease activity [LDA] or remission) and may require multiple therapies and switching between drugs. For patients with RA who fail treatment with a csDMARD, clinical practice guidelines (the American College of Rheumatology [ACR] 2021 and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology [EULAR] 2022) recommend that a bDMARD or a tsDMARD should be added to achieve the treatment target [3, 4]. Further, if a bDMARD or tsDMARD fails, treatment with another bDMARD or tsDMARD (with an alternative mechanism of action) should be considered [3, 4].

Although data exist for the effect on clinical outcomes while switching from a TNFi to other b/tsDMARDs [9], there is limited research on switching from a non-TNFi bDMARD to a tsDMARD [10], and from a tsDMARD to a bDMARD [11, 12]. In these situations, healthcare providers may particularly hesitate to switch between IL-6Ri and JAKi, since they both impact IL-6 signaling [8, 13, 14].

This US-based observational study aimed to explore the effect of switching between IL-6Ri (following discontinuation of JAKi) and JAKi (following discontinuation of IL-6Ri) on disease activity and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in patients with RA.

Methods

Data Source and Patients

The CorEvitas (formerly known as Corrona) RA Registry is a prospective, multicenter, observational disease-based registry launched in US in 2001 [15, 16]. Adult patients with RA enrolled in the registry, who initiated either IL-6Ri (i.e., sarilumab or tocilizumab) or JAKi (i.e., baricitinib, tofacitinib, or upadacitinib) during or after December 2012 (baseline visit) and had a follow-up visit at 6 (± 3) months after therapy initiation, were included in the present study. Eligible patients were divided into two groups: (1) “IL-6Ri initiators” who were initiated on an IL-6Ri following discontinuation of a JAKi and (2) “JAKi initiators” who were initiated on a JAKi following discontinuation of an IL-6Ri.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participating investigators were required to obtain full ethics or institutional review board (IRB) approval for conducting research in patients. The Sponsor approval and continuing review were obtained through central IRB, New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB No. 120160610). For academic sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to the Sponsor prior to initiating any study procedures. All registry patients were required to provide written informed consent prior to participation.

Study Assessments and Outcomes

The main objectives of the study were to assess the changes in disease activity and PROs in the patients with RA switching from an IL-6Ri to a JAKi (and vice versa), and to compare these clinical outcomes between the two groups.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and medication parameters (concurrent medications, prednisone use, prior therapy, and line of therapy) were assessed at baseline. Patient therapy patterns were evaluated between the initiation and the 6-month follow-up visit; the proportion of patients continuing the index therapy at the 6-month follow-up visit and the proportion of patients discontinuing the index therapy at or prior to the 6-month follow-up visit were assessed.

The primary outcome of the study was the mean change in the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from baseline until 6 (± 3) months post-initiation. Continuous secondary outcomes included the mean change from baseline in the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), patient-reported pain (0–100 mm visual analog scale [VAS]), patient-reported fatigue (0–100 mm VAS), tender joint count (TJC, 0–28), swollen joint count (SJC, 0–28), Physician Global Assessment (MDGA, 0–100 mm VAS), Patient Global Assessment (PtGA, 0–100 mm VAS), and morning stiffness duration. Categorical secondary outcomes included the achievement of LDA (CDAI ≤ 10) among those with moderate or high disease activity at baseline (baseline CDAI > 10), and remission (CDAI ≤ 2.8) among those with low, moderate, or high disease activity at baseline (baseline CDAI > 2.8) [17]. Further, minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) were assessed for the following outcomes: HAQ using ≥ 0.3 units improvement from baseline [18], and patient-reported pain, patient-reported fatigue, MDGA, and PtGA using ≥ 10 units improvement from baseline [17, 19,20,21,22,23].

Statistical Analyses

Outcomes after the index b/tsDMARD (IL-6Ri or JAKi) were evaluated at the 6-month follow-up visit post initiation. Patients who switched to any other b/tsDMARD prior to the follow-up visit were excluded; however, those who discontinued without starting any other b/tsDMARD prior to the follow-up were included in this analysis and their responses were evaluated at the 6-month follow-up visit.

Further, to assess the potential impact of the intercurrent event of switching to any other b/tsDMARD prior to the follow-up visit, a sensitivity analysis was performed. For the sensitivity analysis, all outcomes were reanalyzed by imputing non-response for patients who discontinued their index medication prior to the 6-month follow-up. Specifically, “non-response” was imputed for binary outcomes and last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used to impute continuous outcomes.

Disease activity measures and PROs were evaluated at baseline and the 6-month follow-up visit. Continuous outcomes were summarized as unadjusted mean changes from baseline (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]), while categorical outcomes were summarized as response rates (with 95% CIs). Differences in the outcome measures between therapy groups were evaluated using both unadjusted and covariate-adjusted linear and logistic regression models. We reported β (95% CI) for continuous outcomes and odds ratio (OR [95% CI]) for binary outcomes, with JAKi initiators as the reference group.

In the adjusted models, covariates were selected based on an imbalance (defined as |standardized difference (SDi)| > 0.1) between the groups at baseline and effects on the outcome and the primary independent variable (therapy class). |SDi| provides a measure of clinically important difference even when no statistically significant difference is present; |SDi| < 0.1 is commonly taken to indicate a negligible difference between the treatment groups.

All analyses were performed using Stata 15 and/or SAS 9.4.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

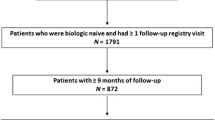

Of 55,069 patients enrolled in the registry, 340 patients initiated an IL-6Ri (following discontinuation of a JAKi; IL-6Ri initiators) and 608 patients initiated a JAKi (following discontinuation of an IL-6Ri; JAKi initiators) during or after December 2012; the enrollment period ended in March 2020. However, 218 IL-6Ri initiators and 464 JAKi initiators did not have a 6-month follow-up visit (Fig. 1). There were three primary reasons for this reduction in the sample of initiators with 6-month follow-up visit: (1) the follow-up visits for the patients occurred outside the 6-month window, (2) the patients did not accumulate 6 months of follow-up at the time of analysis, and (3) the patients were lost to follow-up. Remaining 122 IL-6Ri initiators and 144 JAKi initiators were initially considered for this study. However, 22 IL-6Ri initiators (18%) and 15 JAKi initiators (10%) were further excluded from the main analysis due to switching to a new b/tsDMARD before the 6-month follow-up. Thus, the main analysis included 100 IL-6Ri initiators (82%) and 129 JAKi initiators (90%), and the sensitivity analysis included all IL-6Ri (N = 122) and JAKi (N = 144) initiators.

Patient characteristics were balanced across various measures at baseline; however, some differences were noted in the main analysis. Those switching to IL-6Ri (vs. JAKi) were younger (mean [SD] age: 57.2 [11.3] vs. 59.2 [12.7] years; |SDi|: 0.167), had a higher baseline CDAI (mean [SD] CDAI: 23.9 [13.1] vs. 19.7 [12.9]; |SDi|: 0.324), had used more csDMARDs (prior use of 0, 1, and 2 + csDMARDs: < 5%, 22%, and 74% vs. 4.7%, 30%, and 65%, respectively; |SDi|: 0.197), and had a different concomitant therapy pattern at the time of switch (monotherapy, combination with methotrexate, and combination with other csDMARD: 42%, 24%, and 34% vs. 50%, 30%, and 20%, respectively; |SDi|: 0.317). The detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The findings from the sensitivity analysis were similar and are summarized in Supplementary Materials Table S1 and Table S2.

Among the patients included in the main analysis, 29% of IL-6Ri initiators (n = 29/100) and 25% of JAKi initiators (n = 32/129) discontinued the therapy by the 6-month follow-up visit (Table 3). In the sensitivity analysis population, 42% of IL-6Ri initiators (n = 51/122) and 33% of JAKi initiators (n = 47/144) discontinued the therapy by the 6-month follow-up visit (Supplementary Materials Table S3).

Change in Continuous Clinical Outcomes from Baseline to Follow-Up

Within each group, both IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators saw numerical improvement from baseline for all continuous outcomes, including CDAI, HAQ, patient-reported pain, patient-reported fatigue, TJC, SJC, MDGA, PtGA, and morning stiffness duration. For IL-6Ri initiators, the change from baseline to the 6-month follow-up visit was statistically significant for all outcomes, except the HAQ; for JAKi initiators, a significant improvement was observed only for the patient-reported pain (Table 4). In sensitivity analysis, the change from baseline was significant for most of the outcomes among IL-6Ri initiators, except HAQ, patient-reported fatigue and PtGA, while among JAKi initiators, a significant improvement from baseline was noted only for CDAI, patient-reported pain, and TJC (Supplementary Materials Table S4).

Although unadjusted estimates of mean change were numerically greater for IL-6Ri (vs. JAKi) initiators, both unadjusted and adjusted comparisons of IL-6Ri initiators and JAKi initiators showed no significant differences in the clinical outcomes across treatment groups (Table 4). Similarly, no significant differences were noted between treatment groups in the sensitivity analysis, except for a reduced duration of morning stiffness noted in IL-6Ri vs. JAKi initiators (Supplementary Materials Table S4).

Change in Categorical Clinical Outcomes from Baseline to Follow-Up

Within each group (for both IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators), a significant proportion of patients achieved CDAI LDA, CDAI remission, and MCID for other measures (HAQ, patient-reported pain, patient-reported fatigue, MDGA, and PtGA) (Table 5 and Supplementary Materials Table S5).

Although IL-6Ri (vs. JAKi) initiators had numerically higher unadjusted response rates for most of the clinical outcomes, there were no significant differences noted in the unadjusted comparisons between the two groups (Table 5). The odds of achieving the clinical outcomes were similar between the groups based on the adjusted analysis, except for CDAI LDA. The IL-6Ri initiators (with moderate-to-severe disease) had higher odds of achieving CDAI LDA (adjusted odds ratio, aOR [95% CI]: 3.30 [1.01, 10.78]) than JAKi initiators (Table 5 and Fig. 2).

Adjusted odds ratio for categorical clinical outcomes: change from baseline to 6 months post-initiation (IL-6Ri vs. JAKi initiators). aOdds ratio are shown for IL-6Ri initiators with JAKi initiators as the reference group (presented on a scale of log 2). CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, HAQ Health Assessment Questionnaire, IL-6Ri interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor, JAKi Janus kinase inhibitor, LDA low disease activity, MCID minimal clinically important difference

In the sensitivity analysis, there were no significant differences noted between the treatments, except for the improvement of 10 + units in MDGA (Supplementary Materials Table S5). While the absolute difference in achievement of 10 + units’ improvement in MDGA was similar between IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators (26.8% vs. 31.9%), IL-6Ri initiators reported a higher baseline disease activity based on MDGA (40.3 vs. 31.4; |SDi|= 0.41). Therefore, after adjusting for differences in baseline MDGA, the odds of achieving 10 + units’ improvement in MDGA was lower for IL-6Ri vs. JAKi initiators (OR = 0.49; 0.26–0.94).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of switching from JAKi to IL-6Ri vs. switching from IL-6Ri to JAKi in the same patient population. Our study found that a proportion of patients experienced improvement when switching from one class to the other; the responses were comparable for IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators, except for the achievement of CDAI LDA, which favored IL-6Ri (vs. JAKi) initiators.

Within each group, IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators showed improvement in continuous outcomes, although the changes were not significant for the HAQ among IL-6Ri initiators, and for all the outcomes (except patient-reported pain) among JAKi initiators. This could be due to the relatively low disease activity of the included patients at baseline, which may have made it difficult to measure any significant improvement with the available sample size [24, 25]. A significant proportion of patients still experienced improvement in categorical outcomes within each group, consistent with the well-established efficacy of IL-6Ri and JAKi [26,27,28].

Further, no difference was observed for most outcomes when comparing IL-6Ri with JAKi initiators (after adjusting for differences in the baseline characteristics). Previously, two network meta-analyses (NMAs) compared the efficacy of IL-6Ri with that of JAKi in TNF-inadequate responders (IR), and showed higher ACR20/50 responses with tocilizumab than tofacitinib [29] and higher ACR50 response with sarilumab than baricitinib [30]. However, patients included in the present study (compared with those included in the NMAs) were switching between IL-6Ri and JAKi (not switching from TNFi) and had less disease activity at baseline, history of multiple prior therapies, and longer disease duration, all of which could have made it difficult to detect any differences [24, 25, 31,32,33]. Recently, few other NMAs showed comparable efficacy (relative to placebo) of non-TNFi biologics and JAKi in patients with RA refractory to TNFi treatment, and of bDMARDs and JAKi in patients with inadequate response to bDMARDs [34, 35]. The findings of the present study are consistent with data from a cohort study (based on two observational registries), in which no significant differences were observed for CDAI remission, CDAI 50/70/85, and MCID-based CDAI improvement between tofacitinib and tocilizumab in patients with bDMARD failure [36].

In the present study, patients who switched between IL-6Ri and JAKi had failed treatment with multiple prior b/tsDMARDs and had active disease. For such patients, the ACR and EULAR guidelines recommend treatment with either a bDMARD or a tsDMARD, without preference to any class [3, 4]. This is supported by various studies, which have demonstrated better outcomes in patients with RA, when switching to an alternative mechanism of action therapy after failure of the first-line TNFi [9, 11, 37,38,39], although there is published research showing equivalent results between TNFi cycling and switching to non-TNFi [40]. Limited data exist regarding switching between non-TNFi and JAKi [10], and our study endeavors to address this gap.

While considering the alternative class to switch, there may be hesitancy to switch from an IL-6Ri to a JAKi (and vice versa) as they both work on the IL-6 pathway [8, 13, 14]. However, these therapies have unique mechanisms of action, which could account for the observed outcomes. IL-6 binds to the membrane-bound or the soluble forms of IL-6R, leading to the activation of various intracellular signaling pathways. IL-6Ri works extracellularly to block this IL-6 signaling (and thus, activation of JAK-STAT3, PI3K-PKB/Akt, and Ras/MAPK pathways) along with the regulation of CD4+ T-cells, VEGF, and NLRP3 inflammasome, which are involved in the pathophysiology of RA [14, 41, 42]. On the other hand, JAK enzymes are bound to the intracellular domains of multiple type 1 and type 2 cytokine receptors and are activated by the ligand binding, leading to auto-phosphorylation, activation of the STAT proteins, and ultimately transcription of the pro-inflammatory genes. JAKi primarily acts by interrupting the JAK–STAT signaling (and thus, activation of multiple interleukins [including IL-6], colony stimulating factors, and interferons) along with the suppression of RANKL, CD80/CD86, natural killer cells, TYK2, and NLRP3 inflammasome, which are known to be involved in RA [7, 8, 43, 44].

Although patients experienced improvements in this study (with either direction of switch), it is possible that switching to an alternative mechanism of action therapy that does not directly impact IL-6 signaling could have resulted in a better response. However, this was beyond the scope of our analyses. The main strength of this study was its dataset, based on the large US-based registry with vast geographic representation and robust evaluation [15]. However, as with every retrospective observational study, this study has a few limitations. The study outcomes were evaluated through 6 months only and less than one-third of the IL-6Ri/JAKi initiators could be included in the analyses. There could also be unidentified sources of bias and confounding in the real-world setting, and factors affecting treatment adherence, which would have impacted the study outcomes [45].

Conclusions

In this observational study, both IL-6Ri and JAKi initiators were associated with improvements in clinical outcomes, with comparable responses noted when switching from an IL-6Ri to a JAKi and vice versa. Both IL-6Ri and JAKi therapies are known to have effects on the IL-6 pathway; however, they have distinct mechanisms of action that could account for improvement in disease activity and other outcomes after switching. Overall, switching to an IL-6Ri or a JAKi can be a suitable choice in patients with RA who have an inadequate response to a previous JAKi or IL-6Ri, respectively.

Data Availability

Data are available from CorEvitas, LLC through a commercial subscription agreement and are not publicly available. No additional data are available from the authors.

References

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320:1360–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.13103.

Radu AF, Bungau SG. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Cells. 2021;10:2857. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112857.

Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bergstra SA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:3–18.

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:924–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24596.

Huang J, Fu X, Chen X, et al. Promising therapeutic targets for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:686155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.686155.

Bonelli M, Scheinecker C. How does abatacept really work in rheumatoid arthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:295–300. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0000000000000491.

Harrington R, Al Nokhatha SA, Conway R. JAK inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: an evidence-based review on the emerging clinical data. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:519–31. https://doi.org/10.2147/jir.s219586.

Morinobu A. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Med. 2020;43:148–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/25785826.2020.1770948.

Migliore A, Pompilio G, Integlia D, et al. Cycling of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors versus switching to different mechanism of action therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720X211002682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720x211002682.

Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Combe B, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-BEYOND): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2513–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31116-4.

Fleischmann RM, Genovese MC, Enejosa JV, et al. Safety and effectiveness of upadacitinib or adalimumab plus methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over 48 weeks with switch to alternate therapy in patients with insufficient response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1454–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215764.

Fleischmann RM, Blanco R, Hall S, et al. Switching between Janus kinase inhibitor upadacitinib and adalimumab following insufficient response: efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:432–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218412.

Lin YJ, Anzaghe M, Schulke S. Update on the pathomechanism, diagnosis, and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis. Cells. 2020;9:880. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040880.

Garbers C, Heink S, Korn T, et al. Interleukin-6: designing specific therapeutics for a complex cytokine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:395–412. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.45.

CorEvitas. Rheumatoid arthritis registry. https://www.corevitas.com/registry/rheumatoid-arthritis. Accessed 23 Mar 2022.

Kremer JM. The CORRONA database. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5(1):46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2005.07.006.

Anderson JK, Zimmerman L, Caplan L, et al. Measures of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: Patient (PtGA) and Provider (PrGA) Global Assessment of Disease Activity, Disease Activity Score (DAS) and Disease Activity Score with 28-Joint Counts (DAS28), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Patient Activity Score (PAS) and Patient Activity Score-II (PASII), Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID), Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI) and Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index-5 (RADAI-5), Chronic Arthritis Systemic Index (CASI), Patient-Based Disease Activity Score With ESR (PDAS1) and Patient-Based Disease Activity Score without ESR (PDAS2), and Mean Overall Index for Rheumatoid Arthritis (MOI-RA). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:S14-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20621.

Greenwood MC, Doyle DV, Ensor M. Does the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire have potential as a monitoring tool for subjects with rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:344–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.60.4.344.

Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, et al. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:S240–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20543.

Tubach F, Ravaud P, Martin-Mola E, et al. Minimum clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state in pain and function in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic back pain, hand osteoarthritis, and hip and knee osteoarthritis: results from a prospective multinational study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1699–707. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21747.

Kitchen H, Hansen BB, Abetz L, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for rheumatoid arthritis: minimal important differences review [abstract]. In: 2013 ACR/ARHP annual meeting. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/patient-reported-outcome-measures-for-rheumatoid-arthritis-minimal-important-differences-review/. Accessed 6 Apr 2022.

Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C. Measures of fatigue: Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy (Fatigue) (FACIT-F), Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF), Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), Pediatric Quality Of Life (PedsQL) Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Scale, Profile of Fatigue (ProF), Short Form 36 Vitality Subscale (SF-36 VT), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(Suppl 11):S263–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20579.

Khanna D, Pope JE, Khanna PP, et al. The minimally important difference for the fatigue visual analog scale in patients with rheumatoid arthritis followed in an academic clinical practice. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2339–43. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.080375.

Rubbert-Roth A, Aletaha D, Devenport J, et al. Effect of disease duration and other characteristics on efficacy outcomes in clinical trials of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:682–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa259.

Aletaha D, Funovits J, Ward MM, et al. Perception of improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis varies with disease activity levels at baseline. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:313–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24282.

Strand V, Gossec L, Proudfoot CWJ, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from a randomized phase III trial of sarilumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1614-z.

Strand V, Kosinski M, Chen CI, et al. Sarilumab plus methotrexate improves patient-reported outcomes in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to methotrexate: results of a phase III trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1096-9.

Toth L, Juhasz MF, Szabo L, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors improve disease activity and patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24,135 patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031246.

Lee YH, Bae SC. Comparative efficacy and safety of tocilizumab, rituximab, abatacept and tofacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis that inadequately responds to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19:1103–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.12822.

Choy E, Freemantle N, Proudfoot C, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of sarilumab combination therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors: systematic literature review and network meta-analyses. RMD Open. 2019;5: e000798. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000798.

Aletaha D, Maa JF, Chen S, et al. Effect of disease duration and prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug use on treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1609–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214918.

Kilcher G, Hummel N, Didden EM, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated in trial and real world settings: comparison of randomized trials with registries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57:354–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex394.

Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “To whom do the results of this trial apply?” Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17670-8.

Sung YK, Lee YH. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-tumour necrosis factor biologics and Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis showing insufficient response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46:984–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13380.

Weng C, Xue L, Wang Q, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720X21999564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X21999564.

Mori S, Urata Y, Yoshitama T, et al. Tofacitinib versus tocilizumab in the treatment of biological-naive or previous biological-failure patients with methotrexate-refractory active rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2021;7: e001601. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001601.

Emery P, Gottenberg JE, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Rituximab versus an alternative TNF inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed to respond to a single previous TNF inhibitor: SWITCH-RA, a global, observational, comparative effectiveness study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:979–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203993.

Harrold LR, Reed GW, Magner R, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of rituximab versus subsequent anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with prior exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies in the United States Corrona registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0776-1.

Tanaka Y, Fautrel B, Keystone EC, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients switched from adalimumab to baricitinib due to non-response and/or study design: phase III data in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:890–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214529.

Curtis JR, Kremer JM, Reed G, et al. TNFi cycling versus changing mechanism of action in TNFi-experienced patients: Result of the Corrona CERTAIN comparative effectiveness study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022;4:65–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr2.11337.

Kaur S, Bansal Y, Kumar R, et al. A panoramic review of IL-6: structure, pathophysiological roles and inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020;28: 115327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115327.

Wang H, Wang Z, Wang L, et al. IL-6 promotes collagen-induced arthritis by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the cathepsin B/S100A9-mediated pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88: 106985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106985.

Angelini J, Talotta R, Roncato R, et al. JAK-inhibitors for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a focus on the present and an outlook on the future. Biomolecules. 2020;10:1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10071002.

Yang X, Zhan N, Jin Y, et al. Tofacitinib restores the balance of gammadeltaTreg/gammadeltaT17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome. Theranostics. 2021;11:1446–57. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.47860.

Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1763–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0805-y.

Dua A, Ford K, Fiore S, et al. POS0606: disease activity and patients-reported outcomes after switching between IL-6 receptor inhibitors and JAK inhibitors: an analysis from the Corrona Registry [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:538. Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients, investigators, and associated staff for their participation in this study.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Statistical support for sensitivity analysis was provided by Page Moore of CorEvitas, LLC. Medical writing support for the manuscript was provided by Vasudha Chachra (Sanofi) and Nupur Chaubey (former employee of Sanofi), and was funded by Sanofi.

Authorship

All authors met ICMJE criteria for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

The registry is sponsored by CorEvitas, LLC. This analysis and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Access to study data was limited to CorEvitas and CorEvitas statisticians completed all the analyses; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. CorEvitas has been supported through contracted subscriptions in the last 2 years by AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Chugai, Eli Lilly and Company, Genentech, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, LEO, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc., Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun and UCB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kerri Ford, Stefano Fiore, Dimitrios A Pappas, Jud C Janak, Taylor Blachley, Kelechi Emeanuru, and Joel M Kremer contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work related to this document. Dimitrios A Pappas, Jud C Janak, Joel M Kremer, and Alan Kivitz contributed substantially to the data acquisition for the work related to this document. Anisha B Dua, Kerri Ford, Stefano Fiore, Dimitrios A Pappas, Jud C Janak, Taylor Blachley, Carla Roberts-Toler, Kelechi Emeanuru, Joel M Kremer, and Alan Kivitz contributed substantially to the data analyses or interpretation of the work related to this document. All authors reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Anisha B Dua reports consulting/advisory board for AbbVie, Novartis and ChemoCentryx; and is a board member of Vasculitis foundation and Chicago Rheumatism Society (not paid). Kerri Ford and Stefano Fiore are employees of Sanofi and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. Dimitrios A Pappas reports consulting for Sanofi, AbbVie; Gtech Roche Hellas, and Novartis; is an employee of CorEvitas LLC; has equity interest in CorEvitas, LLC; and is a member of the Board of Directors, Corrona Research Foundation. Taylor Blachley is an employee of CorEvitas, LLC and has no disclosures. Carla Roberts-Toler was an employee of CorEvitas, LLC at the time this study was conducted; currently, she is an employee of Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and has no disclosures. Jud C Janak was an employee of CorEvitas, LLC at the time this study was conducted; and has no disclosures. Kelechi Emeanuru was an employee of CorEvitas, LLC at the time this study was conducted; currently, she is an employee of Evidera and has no disclosures. Joel M Kremer is a consultant for CorEvitas, LLC. Alan Kivitz has received study funding, medical writing support, and article processing charges from Amgen; has received consulting fees from Pfizer, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, AbbVie, Flexion, Gilead, Grunenthal, Orion, Regeneron, Sun Pharma Advance Research, and ECOR1; has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Merck & Co, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Flexion, AbbVie, Amgen, Genentech, Regeneron, UCB, Horizon, and GSK; has participated in a data safety monitoring board for AbbVie and Amgen; has been part of a board or advisory board for AbbVie, Bendcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, ChemoCentryx, Flexion, Gilead, Grunenthal, Horizon, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, UCB, and Novartis; and has stock or stock options in Pfizer, GSK, Gilead, Novartis, and Amgen.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participating investigators obtained full ethics or institutional review board (IRB) approval for conducting research in patients. The Sponsor approval and continuing review were obtained through a central IRB, New England Independent Review Board (NEIRB No. 120160610). For academic investigative sites that did not receive a waiver to use the central IRB, approval was obtained from the respective governing IRBs, and documentation of approval was submitted to the Sponsor prior to initiating any study procedures. All registry patients were required to provide written informed consent prior to participation.

Additional information

Jud C Janak, Carla Roberts-Toler, Kelechi Emeanuru: Affiliation at the time of study. Carla Roberts-Toler: Currently an employee of Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA. Kelechi Emeanuru: Currently an employee of Evidera, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dua, A.B., Ford, K., Fiore, S. et al. Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis After Switching Between Interleukin-6-Receptor Inhibitors and Janus Kinase Inhibitors: Findings from an Observational Study. Rheumatol Ther 10, 1753–1768 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-023-00609-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-023-00609-2