Abstract

The present study aimed to replicate the findings of Dounavi (Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 165–170 2014) by evaluating the effects of foreign tact and bidirectional intraverbal training on emergent verbal relations. Training involved teaching three English-speaking adults to tact visual stimuli according to their foreign (French) referents, and to vocally emit the reverse relation following the presentation of written words in native-to-foreign (English-to-French) and foreign-to-native (French-to-English) intraverbal relations. A modified multiple probe design using pre- and posttraining probes was used to assess the efficacy of each training method in teaching a small foreign language vocabulary and to probe for emergent relations following training. The findings showed that foreign tact and native-to-foreign intraverbal training was more efficient and resulted in greater emergent responding than training in the foreign-to-native relation. Follow-up probes were conducted 4 weeks after the posttraining probes to evaluate the levels of responding for each of the trained and emergent relations. Results from maintenance probes were varied across the trained and emergent relations; it is interesting that the levels of responding in the emergent relations was greater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The development of language fundamentally underpins the ability of an individual to communicate across their lifespan. The processes involved in how language comes to be acquired have been widely researched and debated (e.g., Chomsky, 1959; Skinner, 1957), but the fact is most children will readily acquire their native language without any specific instruction (Sundberg, Michael, Partington, & Sundberg, 1996). The acquisition of a second language, however, is likely to necessitate some level of specific instruction, with the learner’s age at the time of acquisition becoming a crucial factor (Flege & Liu, 2001; Lichtman, 2016). What form that instruction should take is open to debate with many different teaching methods and technology-assisted platforms reported in the literature (e.g., Chamot, 2005; Chen & Kessler, 2013; Liu, Moore, Graham, & Lee, 2002; Norris & Ortega, 2001). However, the fact that there is an increased global demand to speak a second language (Duncan, 2010; European Commission, 2006) means that greater emphasis needs to be placed on identifying the most effective teaching methods. Though the research is relatively limited, there is growing evidence to suggest that behavior analysis has much to offer in foreign language teaching. The paucity in behavior analytical research in this area is surprising given that Sundberg (1991) advocated for a behavioral approach to the acquisition of a foreign language based on Skinner’s (1957) account of verbal behavior. In fact, until very recently, only a handful of studies have been conducted on the subject.

One of the first studies to examine the efficacy of behavior analytic methods in foreign language instruction was carried out by Polson and Parsons (2000) with typically developing adults. Since then, most of the research on foreign language acquisition has been conducted with typically developing children (e.g., May, Downs, Marchant, & Dymond, 2016; Petursdottir & Hafliđadóttir, 2009; Petursdottir, Olafsdottir, & Aradottir, 2008; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Lovett, 2011). Findings from these studies are variable, mainly showing that under certain circumstances behavioral training can be effective in teaching a foreign language and facilitating emergent responding. Indeed, these effects have also been observed in a small number of recent studies conducted with adults (e.g., Dounavi, 2011, 2014). Although preliminary, results in these studies show a greater effect of training adults compared to results attained with children. It is clear that more data are required in order to unveil the underlying principles that make teaching more efficient independent of age or developmental trajectory.

In the context of acquiring a foreign language, four relations are of interest (Petursdottir & Hafliđadóttir, 2009): (1) the foreign tact (i.e., vocalizing the foreign referent of a visual stimulus); (2) the foreign listener (i.e., given a foreign word, the learner orients towards its referent); (3) the native-to-foreign (N-F) intraverbal (i.e., following the presentation of a native word the learner vocalizes its foreign equivalent); and (4) the foreign-to-native (F-N) intraverbal (i.e., opposite of N-F). Though Skinner’s (1957) analysis of these verbal operants suggested they were functionally independent (Miguel, Petursdottir, & Carr, 2005), in some circumstances they are reported to be functional interdependent (Dounavi, 2011, 2014). According to Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir (2009), this is the case when verbal operants share a stimulus or response with their native language equivalents, in which case teaching one relation is likely to facilitate the emergence of other relations. The present study focused on the foreign tact and bidirectional intraverbal relations, as social interactions that involve sharing experiences through tacting and maintaining conversations through intraverbals are more likely to be the goals of teaching with regard to adult learning. Although the listener relation allows some basic contact with a foreign language, it is less likely to be used as a teaching strategy in adult learning and it has proved to be the less efficient in terms of producing emergent responding. Likewise, the mand relation is also limited in that it only provides access to specific reinforcers whereas adults normally seek to sustain more complex social interactions followed by generalized reinforcers when speaking a foreign language.

The rationale accounting for why training one relation could result in the emergence of other relations originates due to the phenomenon of stimulus equivalence (Sidman & Tailby, 1982). However, there are other explanations for derived relations such as the relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes, Blackledge, & Barnes-Holmes, 2001) and the naming hypothesis (Horne & Lowe, 1996), which both give accounts of how language can be derived from seemingly unrelated stimuli in the absence of common formal properties. In the present study, derived responding is plausibly explained by stimulus equivalence, which is considered to have three distinct features (Hayes et al., 2001): reflexivity (i.e., A1 = A1), symmetry (i.e., if A1 = B1, then B1 = A1), and transitivity (i.e., if A1 = B1 and B1 = C1, then A1 = C1). The basic concept behind stimulus equivalence is that an untrained relation can be derived from the fact that there is a shared stimulus or shared response between this taught and an untaught relation, resulting in the shared stimulus or response facilitating the transfer of function towards the untaught relation. A plethora of studies have demonstrated this phenomenon empirically (e.g., Grannan & Rehfeldt, 2012; May, Hawkins, & Dymond, 2013).

When teaching a foreign language, speaker relations are not selection based, as in the traditional stimulus equivalence paradigm, but topography based. For instance, by teaching English to native Spanish speakers, Dounavi’s (2014) research set the premise that by teaching one relation (e.g., English tact), a native Spanish speaker can derive that the English tact is equivalent to the Spanish tact because they share a common stimulus and response with bidirectional intraverbal responses. An example of this is when a learner learns that ball is the English tact of a picture of a ball, they can then derive that ball equals pelota (ball in Spanish) and pelota equals ball.

Other studies conducted with typically developing child populations (e.g., Petursdottir & Hafliđadóttir, 2009; Petursdottir et al., 2008) have also examined the efficacy of behavioral training methods in teaching a foreign language. The Petursdottir et al. (2008) study found that despite the fact posttraining responding was greater than baseline probes, neither foreign tact nor listener responding consistently produced criterion level responding in bidirectional intraverbal relations. Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir’s (2009) findings were also similar in that greater levels of responding were found in posttraining responding compared to baseline probes, but no single training method sufficed to facilitate the emergence of all untrained relations to mastery. However, they did find that the N-F and foreign tact relations were the most efficient training methods in producing emergent responding relative to the F-N and listener relations and that emergent listener relations reached criterion most consistently following training in the other relations. Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir (2009) highlighted a number of factors that may explain their findings, but two are pertinent to discuss. First, they reported that the four probed relations, were functionally independent from each other as per Skinner’s (1957) interpretation of the verbal operants. This explains why no training method sufficed in producing emergent responding across all of the probed relations. Second, they reported that emergent responding failed to occur because insufficient exemplar training was provided in relation to the contextual cues that would be present during the posttraining probes. Indeed, evidence shows that including multiple exemplars during training can increase emergent responding (e.g., May et al., 2016; Rosales et al., 2011). A more recent study by Cortez, dos Santos, Elisa Quintal, Silveira, and de Rose (2020) also shows the variability in the efficiency of behavioral training methods in children, providing further evidence for the independence of verbal relations. Cortez et al. (2020) examined the effect of foreign tact and listener responses on the emergence of bidirectional intraverbal relations. Researchers in this study found that foreign tact training was effective in producing emergent responding bidirectionally whereas following training in foreign listener relations emergent responding in the bidirectional intraverbal relations was variable across participants, with neither emergent intraverbal relation reaching criterion even though greater levels of emergent responding were found in the N-F intraverbal relation.

Research is limited in terms of response maintenance, with the findings to date showing mixed results. Trained relations were maintained significantly higher compared to the derived relations in Rosales et al.’s (2011) study, whereas May et al.’s (2016) research found greater maintenance of the derived relation. A more recent study by Matter, Wiskow, and Donaldson (2020), however, indicates that trained and derived relations are maintained to a greater degree following tact training compared to mixed training methods (i.e., tact, N-F, F-N, and listener training). Generalization, on the other hand, does not always occur following behavioral training (e.g., Rosales et al., 2011, probed generalization using pictures instead of objects).

Evidence suggests that emergent responding is more likely to be facilitated following behavioral training within adult-based research (e.g. Dounavi, 2011, 2014; Polson & Parsons, 2000). Polson and Parsons (2000) have shown that N-F intraverbal training is effective in producing untrained relations in adults. Dounavi (2011) has shown similar effects following foreign tact training, whereas Dounavi (2014) has shown N-F relations and foreign tact training are both effective training methods. In fact, Dounavi (2014) directly compared foreign tact and bidirectional intraverbal training, and found that foreign tact and N-F intraverbal training were effective in producing emergent responding to criterion. Training in the N-F intraverbal was the most effective relative to the foreign tact and the F-N training, therefore suggesting that the efficiency of training methods was differential.

The present study aims to further evaluate the efficacy of foreign tact versus bidirectional training in teaching a small foreign language vocabulary and facilitating emergent responding by systematically replicating Dounavi (2014). In this pursuit, a number of methodological refinements have been made to the current study, as suggested by Dounavi (2014). First, Dounavi (2014) did not conduct a baseline probe in the N-F relation meaning that, although unlikely, it was possible participants correctly guessed the foreign word during probes due to prior testing on foreign tact and F-N relations. An N-F baseline probe was added to the present study to provide for an objective baseline measurement. Second, Dounavi (2014) provided feedback to participants at the end of probe sessions, which could have altered the number of correct responses in subsequent probes, therefore no feedback during probes was provided to participants in the current study. Third, Dounavi did not counterbalance posttraining probes and as such order effects might have influenced outcomes. In the present study, posttraining probes were counterbalanced. Given that this study was a replication of Dounavi, the present study added a third participant, which increases internal and external validity, and a 4-week follow-up probe for the assessment of maintenance, which increases the social validity of research findings.

Method

Participants

Two Irish adults and one Canadian adult residing in a non-French speaking province of Canada participated in the research: Niall, a 31-year-old man; Catriona, a 33-year-old woman; and Brandy, a 40-year-old woman. All participants spoke English as their first language, and scored low on a brief online French language proficiency assessment (http://testfle.campuslangues.com/). However, the three had previously studied French at secondary or high school level for approximately 5 years, and could read any unknown written French words, but could not understand them. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants, whereby people known to the experimenter were emailed an invitation to participate in the study. Prior to commencing the study, approval was obtained by the University Ethics Committee.

Setting

Sessions were conducted in a private space containing a table and at least two chairs in the participants’ homes. Distracting noises were reduced by switching off all electronic devices (e.g., television, radio, phones). The only people present during sessions were the experimenter and the participant, but for approximately one-third of the sessions a second observer was present for the purposes of collecting interobserver agreement (IOA) data.

Materials and Stimulus Sets

A list of 50 words was generated based on animals, common objects, and foods. Then three stimulus sets were generated from this list by randomly assigning 10 stimuli to each set (Table 1). The nonverbal stimuli (i.e., pictures) used in the data sets were retrieved from the internet using Google® Images; their English referents were sourced by asking participants to tact the images in English. This process was completed to eliminate any ambiguity during sessions by ensuring that all participants were using the same native referents (e.g., whether they should tact ‘Airplane’ or ‘Aircraft’ when presented with a picture of an airplane) and to incorporate these in the N-F probes. Following this process, the English words where subsequently translated into French using Google® Translator and validated using an English to French online dictionary. Data were presented on a 15” HP Pavilion® laptop computer having been integrated into Microsoft PowerPoint® 2010 using an average dimension of 11cm x 12cm for each image and Calibri font size 56 for textual data. French words ranged from four to nine letters and contained a maximum of three syllables; any words that sounded similar to English words or were familiar to participants were not used (e.g., Miroir meaning “Mirror”). All stimuli presented in Microsoft PowerPoint® were centered and positioned against a white background. A data recording sheet and black pen were used to record correct and incorrect responses during each session.

Three conditions were used in the study: baseline probes, training sessions, and posttraining probes. Following the completion of posttraining probes, a 4-week follow-up assessment was conducted to evaluate response maintenance on trained and emergent relations. The discriminative stimuli for each of the three conditions were textual (i.e., written words, a slight variation from Dounavi (2014), who presented intraverbal stimuli vocally) for F-N intraverbals for Set 1, pictorial for foreign tacts for Set 2, and textual for N-F intraverbals for Set 3. The use of a textual discriminative stimulus and vocal response differed from Dounavi’s study because common foreign language instruction involves learning from books (Dounavi, 2014). This change might make our training more effective due to the static nature of textual stimuli that allow participants to stay in contact with them for a full 3 s, as opposed to the volatile nature of auditory stimuli. Data for each set were integrated into three Microsoft PowerPoint® presentations with written French words (Set 1), pictures (Set 2), and written English words (Set 3) appearing on the screen for 3 s, which is the typical response time expected for a fluent speaker (Dounavi, 2011). For each stimulus set, a total of four to seven sessions were conducted per day, with intersession intervals ranging from 30 s to 3 min, and days between sessions ranging from 1 to 4 days. Nine response maintenance sessions were conducted on a single day for each participant at least 28 days after posttraining probes. Following Dounavi’s (2014) protocol, the order of presentation for target textual stimuli for each stimulus set across sessions was unchanged simulating common learning materials (e.g., lists of translated words in books).

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables were the number of correct responses in (1) the F-N intraverbal, defined as vocalizing the English referent when presented with a written French word, (2) the foreign tact, defined as vocally labeling a picture in French, and (3) the N-F intraverbal, defined as vocalizing the French referent after being presented with its English written equivalent. In order for a correct response to occur a participant was required to vocally emit a response within 3 s following the presentation of the discriminative stimulus. For the purposes of the present study French words were required to be articulated correctly to be deemed correct as determined by the experimenter using a phonetic spelling checklist and native language synonyms in the F-N intraverbal were recorded as correct. Incorrect responses were recorded when a participant did not emit the correct word, gave no response, and/or emitted more than one response within 3 s of the discriminative stimulus presentation. Data were recorded continuously during sessions.

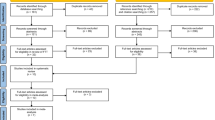

Experimental Design

A modification of the concurrent multiple probe across participants design was used, as originally described by Horner and Baer (1978), to evaluate the effect of foreign tact and bidirectional intraverbal training on the emergence of untrained responses. The modification to the original multiple probe design consisted of conducting only one probe for each relation based on the assumption that it was highly unlikely that participants would learn the untaught relations spontaneously/without any instruction. In fact, all but one first data points of the intervention condition were 0, confirming this assumption.

The effects of training on emergent responding was evaluated using pre- and posttraining probes with stimulus sets replicated across participants in accordance with Dounavi’s (2014) design; a follow-up response maintenance probe was also added as part of the systematic replication of Dounavi’s study. Baseline probes were presented in the following order: F-N, foreign tact, and N-F, and for posttraining probes the three 10-stimulus sets were counterbalanced and randomly presented to each participant. During the response maintenance probes, trained relations were probed first, followed by the emergent relations. Maintenance probes for trained relations were counterbalanced across participants, whereas probes for emergent relations used the same presentation order as the posttraining probes.

Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

Data were collected independently by a second observer across all experimental conditions. For each session, IOA was calculated on a trial by trial basis by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of trials, and multiplying by 100. IOA data for Niall were collected in 33% of baseline probe sessions (mean IOA agreement = 100%), in 33% of training sessions (mean IOA agreement = 98.5%), ranging from 97.5% to 100%, in 50% of posttraining probes (mean IOA agreement = 100%), and in 50% of response maintenance probes (mean IOA agreement = 100%). For Brandy, IOA data were collected in 33% of baseline probe sessions (mean IOA agreement = 100%), in 35% of training sessions (IOA agreement ranged from 95% to 100%, mean IOA = 98.1%), in 50% of posttraining probes (mean IOA agreement = 100%), and in 100% of response maintenance probes (mean IOA agreement = 100%). Catriona’s IOA data were collected in 33% of baseline probe sessions (mean IOA agreement = 100%), in 40% of training sessions (IOA agreement ranged from 98.3% to 100%, mean IOA was 99.6%), in 50% of posttraining probes (mean IOA agreement = 100%), and in 33% of response maintenance probes (mean IOA agreement = 100%).

Procedure

Baseline probes

Each of the three 10-stimulus sets was tested in the baseline probes and was presented to participants via PowerPoint® to identify unknown stimuli that could be used during training and posttraining probe sessions. This consisted of presenting the F-N intraverbal stimulus set to participants (i.e., written French words) and instructing them to say the equivalent English word, then presenting the foreign tact stimulus set and instructing them to label the picture in French and subsequently presenting the N-F set, which followed the reverse procedure of the F-N set. Stimulus sets were presented simultaneously in this order for all participants. As per Dounavi (2014), the N-F intraverbal probe was added to baseline probes to provide for an objective measurement of participants’ baseline repertoire. No feedback was provided by the experimenter during any of the baseline probes to eliminate the possibility of participants deducing the correct responses. Any instance where a French word was known to a participant during the baseline probes, the word was removed from the stimulus set and substituted for another French word for all participants (e.g., the French word Maison for house was removed, as two of the three participants were able to state “House” when presented with the written word Maison). A second baseline probe was consequently conducted including the newly added word.

Training

Following baseline probes, training sessions were conducted for each of the 10-stimulus sets in random order for each of the participants. All three stimulus sets were simultaneously taught to each participant with each set being presented in a random order across sessions to rule out order effects. In F-N intraverbal training, participants were taught to vocalize the English referent when presented with the written French word (e.g., to say “Candle” following the presentation of Bougie). During foreign tact training, participants were trained to label pictures in French, such as to respond Couteau to a “Picture of a Knife.” Training in the N-F direction involved teaching participants to vocalize the French referent when presented with a written word in English (e.g., to say Chapeau when presented with “Hat”). In each training trial, the correct textual response was presented on a new screen 3 s after the presentation of the discriminative stimulus, which served as feedback following correct responses and as correction following incorrect responses. Training was the only condition where feedback was provided to participants. Correct responding was praised at a random rate of approximately one in every three trials (e.g., “you got that right, great job”). At the end of every training session, if participants achieved a higher correct number of responses than the previous session they received social praise (e.g., “you scored higher than the previous session, well done”). If the correct number of responses did not improve at the end of a session, participants were encouraged to try harder (e.g., “you have been trying so hard, let’s see if you can improve your score on the next session”). Training continued until participants scored 10 out of 10 correct responses in two consecutive sessions. Then the order of presentation of the stimuli in the training sets were randomized across each subsequent session until participants scored 10 out of 10 across two consecutive sessions. Thus, the mastery criterion during training was set at 10 out of 10 correct responses across two consecutive sessions and two different orders of stimuli presentation.

Posttraining probes

Posttraining probes were conducted on the two untrained relations for each of the three 10-stimulus sets. In other words, following F-N intraverbal training, participants were probed in the foreign tact condition and the N-F condition (e.g., after being trained to vocalize “Candle” following the presentation of Bougie, participants were probed to see if they could respond Bougie when presented with a picture of a candle or the word “Candle”). For the foreign tact training, probes were conducted on the F-N and N-F intraverbal relations (e.g., participants were trained to vocalize Bougie following the presentation of a picture of a candle, and then probed to see if they could vocalize Bougie when presented with the word “Candle” or vice versa for the F-N relation). The N-F posttraining probes were conducted using the same procedure as the F-N probes but with intraverbal relations reversed. As a systematic replication of Dounavi (2014), the present study randomized and then counterbalanced the order of presentation of verbal operants during posttraining probes for each participant to control for order effects.

The mastery criterion for posttraining probes was 10 out of 10 correct responses. If participants did not achieve mastery scores, but scored 7 or greater out of 10, then a second probe was conducted to examine if they could achieve mastery. During the posttraining intraverbal probes, participants who scored fewer than 7 out of 10 in the original probe or fewer than 10 in the second probe were trained again in the reverse intraverbal relation. Following this training, the tact relation was probed again (i.e., the N-F relation was trained again when mastery scores were not met in the F-N relation or vice versa, and then the tact relation was probed). If mastery scores were not met in this probe, no further probes were conducted. In line with Dounavi (2014), the experimenter provided no feedback to participants during posttraining probes to rule out the possibility that they may deduce the correct responses.

Response maintenance probes

Follow-up response maintenance probes were conducted approximately 4 weeks after the posttraining probes for all three sets and each of the participants. In each of the stimulus sets, the relation the participants were trained in and the two corresponding emergent relations were probed (e.g., the trained F-N relation was probed first followed by the emergent foreign tact and N-F relations). This order ensured that maintenance assessment captured maintenance of the trained operant independently first, before assessing maintenance of collateral gains (i.e., emergent responses). Mastery criterion for response maintenance probes was 10 out of 10 correct responses. As per the baseline probe and posttraining probe conditions during Dounavi’s (2014) study, no feedback was provided to participants.

Results

Foreign to Native Intraverbal Training

In the F-N intraverbal condition (Figure 1), all participants scored 0 in the baseline probes across all relations. During F-N intraverbal training, mastery criterion (i.e., 10 out of 10 correct responses for two consecutive sessions) was reached after 13 sessions for Niall, 15 for Brandy, and 19 for Catriona (Table 2). In the N-F and foreign tact posttraining probes, only Niall reached criterion, whereas Brandy scored 7 out of 10 for each of the probed relations and Catriona scored 4 out of 10 for the N-F relation and 2 out of 10 for the foreign tact relation. As Brandy scored at least 7 out of 10 for each relation in the first probe, a second probe was conducted where she scored 8 out of 10 in both relations. Therefore, further training in the reverse relation (i.e., the N-F intraverbal) was provided to both Brandy and Catriona requiring 3 and 12 sessions, respectively, to meet criterion. Following the reverse intraverbal training both Brandy and Catriona’s scores met mastery criterion in the probe for the foreign tact relation.

Regarding results of response maintenance probes for the trained F-N relation and emergent foreign tact and N-F relations, none of the participants reached mastery criterion, although they all showed some level of responding. Overall, levels of responding were greater or equal to responding during the N-F relation and the foreign tact posttest.

Foreign Tact Training

In the foreign tact condition (Figure 2), baseline probes showed 0 correct responses across relations and participants. During foreign tact training, Niall reached mastery criterion after 11 sessions, Brandy after 13, and Catriona after 15 (Table 2). In posttraining probes, Niall and Brandy reached mastery criterion in probed emergent relations in one trial, whereas Catriona reached mastery criterion in two sessions.

In maintenance probes, none of the participants reached mastery criterion in both trained and emergent relations, but Brandy’s scores met criterion in the emergent F-N and N-F relations. It is interesting that responding in the trained foreign tact relation was maintained the least for Niall and Brandy compared to emergent relations, whereas it was also low for Catriona but higher than the F-N relation.

Native to Foreign Intraverbal Training

In the N-F intraverbal condition (Figure 3), zero scores were obtained in baseline probes. During training in the N-F intraverbal, Niall’s scores met mastery criterion after 13 sessions, Brandy after 11, and Catriona after 6 (Table 2). In the posttraining probes, both Niall and Brandy’s scores met criterion in the foreign tact relation at the first probe, whereas Catriona’s scores met criterion at the second probe. All participants’ scores met criterion at the second probe in the F-N intraverbal relation.

The results of maintenance probes show that Brandy’s scores met criterion at the emergent F-N intraverbal, whereas Catriona scored 9 out of 10 in the same relation. The same participants scored 9 out of 10 in the emergent foreign tact probe. Across participants, the highest levels of responding during maintenance probes were found in the emergent foreign tact relation (i.e., Niall 7, Brandy 9, and Catriona 9) and the emergent F-N relation (i.e., Niall 5, Brandy 10, and Catriona 9), except for marginal differences with one participant (Niall). It is interesting that the trained N-F relation was the least maintained (Niall 4, Brandy 8, and Catriona 3) across all participants, although marginal differences were observed compared to the tact and F-N relations with one participant (Brandy) and between the F-N and N-F relations for another (Niall). Therefore, levels of responding were greater in the emergent relations relative to the trained N-F relation.

Discussion

The present study replicated Dounavi’s (2014) research using an improved methodology to compare the effect of foreign tact and bidirectional intraverbal instruction on the acquisition of a foreign language vocabulary and assess its effect on emergent responding and maintenance of acquired relations. Results showed that all training methods were effective in teaching a foreign language vocabulary, but the efficiency of training was differential in terms of rate of acquisition, emergent responding, and response maintenance. The findings showed that criterion was reached in fewer trials following N-F intraverbal instruction for two of the three participants relative to training in the foreign tact and F-N intraverbal relations, with larger differences observed for only one participant (Catriona). In posttraining probes, foreign tact and N-F intraverbal training were effective in producing untrained responses for all participants, with a slightly greater effect found following foreign tact training. Given only one participant’s scores met mastery in post-F-N training probes, this method was the least effective in facilitating derived responding. Additional training in the reverse relation for the other two participants was shown to be effective in producing derived responding to mastery in the foreign tact posttraining probe. Follow-up response maintenance probes showed that response rates were maintained to varying degrees; however, levels of responding in the emergent relations was more likely to be higher than the trained relations. In general, responding was more likely to be maintained in the emergent relations following N-F intraverbal and foreign tact training relative to the F-N relations, an interesting finding observed in this study for the first time.

The efficiency of N-F intraverbal training in producing emergent responding as demonstrated in the present study has also been shown in a number of previous studies (e.g., May et al., 2016; Petursdottir & Hafliđadóttir, 2009; Polson & Parsons, 2000). Of these studies, however, the Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir (2009) study was the only one to directly compare the efficiency of N-F intraverbal training to the F-N relation, and like the present study found that N-F intraverbal training produced greater levels of emergent responding than the F-N relation. Yet, the present findings also conflicted with those of Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir’s (2009) study in two areas. First, the F-N intraverbal required fewer training sessions than the N-F and foreign tact relations in reaching criterion. This is in contrast to the present study, which found N-F training reached criterion in fewer trials. Second, in the present study the foreign tact relation training was also found to be effective in producing emergent responding in bidirectional intraverbal relations. Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir (2009) found that foreign tact training was only effective in one direction (the N-F relation), though they did also find it to be effective in terms of emergent listener responses. Likewise, contrary to the present findings, Petursdottir et al. (2008) also found that foreign tact training was only effective in producing emergent responding in the N-F relation. However, the differences between the present study and the studies conducted by Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir (2009) and Petursdottir et al. (2008) could be attributed to the differences in ages between participants. Nevertheless, more recent research has supported the findings of the present study in that foreign tact training was effective in producing emergent responding bidirectionally in the intraverbal relations (e.g., Cortez et al., 2020).

Given that there are only three studies that previously researched response maintenance following behavior analytical training in foreign language instruction using different methodologies, it is difficult to make comparisons with the present findings. The first study to assess response maintenance was conducted by Rosales et al. (2011) following their evaluation of foreign listener training on emergent foreign tact responding. They examined maintenance of both the trained (i.e., foreign listener) and emergent (i.e., foreign tact) relations, and found that only responding in the trained relation was reliably maintained for one participant, but not to mastery. However, the opposite effect was found in the present study where the rate of responding was maintained to a higher degree in the emergent relations relative to the trained relations. In another study, May et al. (2016) assessed response maintenance probes following their examination of native listener and N-F intraverbal training on emergent foreign tact and foreign listener relations. The study only assessed the maintenance of emergent responding conducting probes at 2-, 3-, and 4-week intervals. Maintained levels of responding were significant for all participants, except one, consistent with the findings of the present study that also showed that emergent responding was significantly maintained. Given May et al. (2016) did not compare response maintenance of trained versus emergent relations, any comparisons with their findings needs to be made tentatively. The study by Mallet et al. (2020), which assessed the maintenance of trained and derived responding following tact and mixed training (i.e., tact, N-F, F-N, and listener training), indicated that responses were more likely to be maintained for both the trained and derived relations following tact training. This differs from the findings of the present study, which found that derived relations were more likely to be maintained than the trained relations following foreign tact training.

In the present study, there were three minor procedural differences from those used by Dounavi (2014). First, there were fewer stimuli (10 vs. 30) used in the data sets during training, therefore posttraining and maintenance probes might have yielded higher results overall. Second, the present study did not conduct experimental sessions on consecutive days like Dounavi and it is possible that this affected the number of training sessions required for participants to reach mastery in training. Additionally, Dounavi used vocal verbal discriminative stimuli whereas the present study used textual verbal stimuli (i.e., we used written words on the screen vs. spoken words). These differences, however, appear to have had a minimal impact on the findings given the same pattern of responding was observed across the present and Dounavi’s studies. In addition, the present study did not conduct treatment integrity; thus, it is not possible to provide evidence in relation to the integrity of the application of the independent variable during the study.

Previous research on response maintenance did not show any potential limitations in relation to the order of presentation, but it is possible that sequential order effects affected present findings on response maintenance. That is, the present study first assessed maintenance in the trained relations and then in the emergent relations. The findings of the present study that emergent relations were maintained to a greater degree suggests that the prior exposure to the stimuli in the trained relations might have carried over to the emergent probes as there was a shared stimulus or response between the relations from each condition. For example, in a foreign tact training probe if the participant failed to say Chien following the presentation of a “Picture of a Dog,” during the emergent F-N probe when presented with the word Chien it is likely that the participant would now vocalize correctly “Dog” because this response shares a relation with the picture they were previously exposed to, for already being part of their repertoire (i.e., stimulus generalization where stimuli share a response). Thus, it is more easily evoked by new stimuli compared to responses that are not established in one’s repertoire. This explains why tacts and N-F training produce the best outcomes in terms of emergent responses (i.e., both instructional strategies establish new responses that are afterwards evoked by new stimuli). This is a common observation in real life settings as well, where individuals who in a distant past have been fluent in a foreign language but have not been exposed to the relevant contingencies for years, can regain fluency in that language soon after coming in contact with these contingencies again compared to individuals who had never acquired fluency (Higby & Obler, 2015). As such, future studies should consider randomizing probes to avoid possible carryover effects.

The most salient issue that needs to be discussed is why the effect of behavior analytic training on emergent responding differs across the literature. One of the key reasons for this, according to Dounavi (2014), is that previous studies (e.g., Petursdottir & Hafliđadóttir, 2009; Petursdottir et al., 2008) have carried out their research within child populations. According to Dounavi, the observed absence of emergent relations in child-based studies is due to children being less verbally competent than adults. In other words, children have had far fewer opportunities to transfer stimulus control from trained to emergent relations relative to adults, therefore this pivotal skill might still be weak or completely absent from their behavioral repertoire. The implications of these findings are significant in terms of developing effective teaching methods that support the acquisition of a foreign language and emergent responding. This is due to the fact that behavioral methods would be limited if they could only suffice in teaching a foreign language to adult populations. However, within the literature (e.g., May et al., 2016; Rosales et al., 2011) there is evidence to show that the inclusion of multiple exemplar training can significantly increase emergent responding following the failure of other methods to produce the same effect. It is, therefore, recommended that future studies further examine the effects of multiple exemplar training in facilitating emergent responding in child-based studies. It would also be of great value to arrange teaching procedures that provide multiple opportunities for children to engage in derived responding with a foreign language learning setting so that researchers can observe how this might increase emergent responding even further (i.e., whether there is a learn-to-learn effect).

A second issue that needs to be addressed is the observations regarding the effectiveness of the F-N intraverbal training in facilitating emergent responding. To date, research consistently shows that training in the N-F intraverbal and foreign tact relations have a greater effect on the emergence of untrained verbal relations relative to the F-N relation. It is often cited (e.g., Dounavi, 2014; Petursdottir & Hafliđadóttir, 2009) that this effect demonstrates the functional independence of the verbal operants in line with Skinner’s (1957) account of verbal behavior. Polson and Parsons (2000) highlight that the functional independence is observed in the F-N relation because of the fact that the reverse relation (i.e., N-F) requires a response in the foreign language that is less accessible than a response in the native language. In addition, Petursdottir and Hafliđadóttir (2009) suggest that studies that fail to demonstrate emergent responding may lack sufficient exemplar training. The implications of this for future studies is that further consideration needs to be given to the functional independence of the verbal operants and the effect this might have on emergent responding (Dounavi, 2014). Future studies could examine in which relations is independence observed and which stimulus–response combinations can facilitate transfer of functions across relations.

The paucity in the research examining the maintenance of foreign language responses following behavioral training is another area that requires further examination, because maintenance is key to drawing conclusions on the most efficient teaching procedures. The social validity of behavior analytic instruction in teaching a foreign language and facilitating emergent responding would also be increased if behavioral training demonstrated maintenance of acquired foreign language vocabulary. Future research should carefully consider the findings of the present study in relation to the order in which response maintenance probes were presented. Further research also needs to be conducted on stimulus generalization of acquired foreign language responses because only one previous study (Rosales et al., 2011) examined generalization, indicating behavioral training was ineffective in facilitating generalized responding.

Ethical Considerations

This study has been granted ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the University where the study was completed. All aspects adhered to the Behavior Analysts Certification Board Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2014) and University ethical standards.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Chamot, A. U. (2005). Annual review of applied linguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, X. B., & Kessler, G. (2013). Action research tablets for informal language learning: Student usage and attitudes. Language Learning & Technology, 17(1), 20–36.

Chomsky, N. (1959). A review of B. F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior. Language, 35(1), 26–58.

Cortez, M., dos Santos, L., Quintal, A. E., Silveira, M. V., & de Rose, J. C. (2020). Learning a foreign language: effects of tact and listener instruction on the emergence of bidirectional intraverbals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(1), 484–492.

Dounavi, A. (2011). A comparison between tact and intraverbal training in the acquisition of a foreign language. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 12(1), 239–248.

Dounavi, K. (2014). Tact training versus bidirectional intraverbal training in teaching a foreign language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 165–170.

Duncan, A. (2010). Education and the language gap. Foreign Language Summit, University of Maryland, Hyattsville. Retrieved January 3, 2018, from https://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/education-and-language-gap-secretary-arne-duncans-remarks-foreign-language-summit

European Commission. (2006). Europeans and their languages (Special Eurobarometer 243/Wave 64.3: TNS Opinion and Social). Retrieved September 3, 2019, from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_243_en.pdf

Flege, J. E., & Liu, S. (2001). The effect of experience on adult’s acquisition of a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 23(4), 527–552.

Grannan, L., & Rehfeldt, R. A. (2012). Emergent intraverbal responses via tact and match-to-sample instruction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(3), 601–605.

Hayes, S. C., Blackledge, J. T., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2001). Language and cognition: Constructing an alternative approach within the behavioral tradition. In S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & B. Roche (Eds.), Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition (pp. 3–20). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Higby, E., & Obler, L. (2015). Losing a first language to a second language. In J. Schwieter (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingual processing (pp. 645–664). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107447257.

Horne, P. J., & Lowe, C. F. (1996). On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 65(1), 185–241.

Horner, R. D., & Baer, D. M. (1978). Multiple-probe technique: A variation of the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(1), 189–196.

Lichtman, K. (2016). Age and learning environment: Are children implicit second language learners? Journal of Child Language, 43(3), 707–730.

Liu, M., Moore, Z., Graham, L., & Lee, S. (2002). A look at the research on computer-based technology use in second language learning: A review of the literature from 1990–2000. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 34(3), 250–273.

Matter, A. L., Wiskow, K. M., & Donaldson, J. M. (2020). A comparison of methods to teach foreign-language targets to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(1), 147–166.

May, R. J., Downs, R., Marchant, A., & Dymond, S. (2016). Emergent verbal behavior in preschool children learning a second language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(3), 711–716.

May, R. J., Hawkins, E., & Dymond, S. (2013). Brief report: Effects of tact training on emergent intraverbal vocal responses in adolescents with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(4), 996–1004.

Miguel, C. F., Petursdottir, A. I., & Carr, J. E. (2005). The effects of multiple-tact and receptive-discrimination training on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 21(1), 27–41.

Norris, J., & Ortega, L. (2001). Does type of instruction make a difference? Substantive findings from a meta-analytic review. Language Learning, 51(1), 157–213.

Petursdottir, A. I., & Hafliđadóttir, R. G. (2009). A comparison of four strategies for teaching a small foreign-language vocabulary. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(3), 685–690.

Petursdottir, A. I., Olafsdottir, A. R., & Aradottir, B. (2008). The effects of tact training and listener training on the emergence of bidirectional intraverbal relations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(3), 411–415.

Polson, D. A. D., & Parsons, J. A. (2000). Selection-based versus topography-based responding: An important distinction for stimulus equivalence? Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 17(1), 105–128.

Rosales, R., Rehfeldt, R. A., & Lovett, S. (2011). Effects of multiple exemplar training on the emergence of derived relations in preschool children learning a second language. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27(1), 61–74.

Sidman, M., & Tailby, W. (1982). Conditional discrimination vs. matching to sample: an expansion of the testing paradigm. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 37(1), 5–22.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Sundberg, M. L. (1991). 301 research topics from Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 9(1), 81–96.

Sundberg, M. L., Michael, J., Partington, J. W., & Sundberg, C. A. (1996). The role of automatic reinforcement in early language acquisition. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 13, 21–37.

Availability of Data and Materials

Raw data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daly, D., Dounavi, K. A Comparison of Tact Training and Bidirectional Intraverbal Training in Teaching a Foreign Language: A Refined Replication. Psychol Rec 70, 243–255 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-020-00396-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-020-00396-0