Abstract

Purpose of the Review

The review synthesises the current knowledge of post-windstorm management in selected European countries in order to identify knowledge gaps and guide future research.

Recent Findings

Despite the differences in forest ownership and national regulations, management experiences in Europe converge at (1) the need for mechanization of post-windthrow management to ensure operator safety, (2) the importance to promote operator training and optimise the coordination between all the actors involved in disturbance management and (3) the need to implement measures to consolidate the timber market while restoring forest ecosystem services and maintain biodiversity.

Summary

Windstorms are natural disturbances that drive forest dynamics but also result in socio-economic losses. As the frequency and magnitude of wind disturbances will likely increase in the future, improved disturbance management is needed. We here highlight the best practices and remaining challenges regarding the strategic, operational, economic and environmental dimensions of post-windthrow management in Europe. Our literature review underlined that post-disturbance management needs to be tailored to each individual situation, taking into account the type of forest, site conditions, available resources and respective legislations. The perspectives on windthrown timber differ throughout Europe, ranging from leaving trees on site to storing them in sophisticated wet storage facilities. Salvage logging is considered important in forests susceptible to bark beetle outbreaks, while no salvage logging is recommended in forests protecting against natural hazards. Remaining research gaps include questions of balancing between the positive and negative effects of salvage logging and integrating climate change considerations more explicitly in post-windthrow management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Windstorms are natural agents of forest disturbance. They shape forest ecosystem structure and composition and account for more than 50% of the timber disturbed in European forests [1]. Recent findings confirm that storms have already increased in Europe in the past decades [2], and an increase in wind disturbances is expected in the coming decades [3]. The storms that occurred in December 1999, for instance, had a critical impact on the forests of several European countries, e.g. Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland [4]. The estimated total damage of these storms was 180 million m3, i.e. three quarters of the planned annual harvest in Europe [4], resulting in an economic loss of approximately ten billion euros [5]. In January 2005, storm Gudrun hit southern Sweden with average wind speeds of 33 m s−1 and gusts of up to 42 m s−1 [6]. Approximately 70 million m3 of timber was disturbed which was almost as much as the average annual cut for the whole of Sweden [7]. In Poland, the severe weather event of 11 August 2017, when peak gust wind speeds exceeded 42 m s−1, was one of the most severe storms in the history of the country [8]. It was initially estimated, that 79,700 ha of forest was disturbed, with damage of 9.8 million m3 of timber [8]. In 2018, storm Vaia hit northeastern Italy with winds blowing at 55.6 m s−1, affecting 42,000 ha in three regions and disturbing over 8 million m3 of timber [9]. An overview of the regions affected, wind speed and volume of timber disturbed is presented in Table 1 [10, 11].

From the point of view of forest operations, wind disturbances lead to significant challenges mainly due to the organisation of salvage logging and work safety. They also affect forest management at strategic (e.g. logistics, labour and storage capacities, etc.) and economic levels (e.g. reduced timber prices, additional costs for re-planting, etc.). In addition, post-disturbance management also needs to consider the environmental impact such as decreased carbon sequestration, growing stock and variable biodiversity response. Trade-offs between the recovery of economic losses via salvage logging and the resulting impact on the environment due to harvesting operations potentially lead to conflicts between forest managers, people seeking recreation in forests, conservationists and policy-makers [12•]. At larger spatial scales, dealing with the potential collapse of the wood market after a large-scale storm event is of major concern to decision-makers [4]. There is a growing body of information regarding the impact of windstorms on European forests, and a number of best practice examples have been developed for responding to wind disturbances in management. However, this information is scattered and often published in languages other than English [1]. Previous efforts to synthesise experiences of managing wind disturbances across Europe date back several years [4]. An update on viable strategies for post-disturbance forest management [13••, 14••] is needed, in particular considering the context of climate change and the resulting change in the frequency and magnitude of extreme events.

To compile a state of the art in operational responses to wind disturbances in Europe, the literature from six European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Sweden and Switzerland) was reviewed. The current knowledge of post-management practices in four key management dimensions was synthesised, analysing the (i) strategic, (ii) operational (including safety), (iii) economic and (iv) environmental aspects of managing wind disturbances. This review is intended to help forest managers and policy-makers to establish benchmarks and respond efficiently to future windstorm events in European forests.

Methods: Systematic Literature Review

The aim of this literature review was to summarise existing experiences in the post-disturbance management of windstorms published in primary, secondary and tertiary sources. Primary sources provide first-hand evidence published in the scientific literature, while secondary sources describe, analyse and interpret information obtained from primary sources (e.g. review and synthesis papers). Tertiary sources represent the grey literature that is not included in the previous two categories (e.g. research reports, documents of governments and management bodies). The focus of the analysis was on European countries with strong forest economies which are frequently affected by wind disturbances, namely, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Sweden and Switzerland. In general, systematic reviews are preferred since they use the full range of available evidence to analyse the state of the art in a specific field [15].

A literature search was carried out in English on the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus in July 2020, and updated in January 2021. In each search string, a disturbance term (e.g. “windthrow”) and an intervention term (e.g. “salvage logging”) were included (Table S1). The logical (Boolean) search operators “AND” as well as “OR” were used to filter records based on more than one condition, while the “*” operator was used to include all derivatives of the key search terms. A search was made for terms in the title, abstract and keyword fields. To complete the bibliography, the reference list of relevant articles was screened, and grey literature sources in all five languages (French, German, Italian, Polish and Swedish) were included. Specific searches were also conducted using country-specific search engines (e.g. HAL for French publications) and forestry-related websites, namely, FCBA (https://www.fcba.fr/), the Austrian, German and Swiss platform “Waldwissen” (www.waldwissen.net), the Italian Academy of Forest Science and the Compagnia delle Foreste publishing database (https://italianforestscience.academy/), the State Forests in Poland (www.lasy.gov.pl), the Swedish Forest Agency (https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/en/) and the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment FOEN (https://www.bafu.admin.ch/).

Relevant references were filtered in a stepwise selection procedure. First, the titles were screened and irrelevant references (e.g. fire disturbances) were discarded. Second, the abstracts were read and those referring to strategic, operational (including safety), economic or environmental aspects of post-windstorm management were retained. Furthermore, studies with global and European coverage were retained as long as they were related to the above-mentioned countries. Any references not connected to the six focal countries were discarded. The relevant information was extracted and stored in an Excel spreadsheet (i.e. DOI, title, journal, author, year, source, country, language, keywords, search algorithm and search engine (Table S1)). The final list of relevant literature was sent to all the authors to assess its completeness. From the retained references, 68% were from primary sources, 13% from secondary and 19% from tertiary sources.

The references were categorised into four important dimensions of post-disturbance management: (1) strategy, (2) operations and safety, (3) economics and (4) environment. Strategic aspects refer to those addressing the long-term consequences, e.g. post-disturbance management decisions such as “clearing or keeping” as well as those discussing organisational aspects at the national level (e.g., central humidity-controlled storage capacities, organised by the state and open for all forest owner). “Operations and safety” summarises literature addressing issues related to field operations, machinery, work safety, transportation, timber storage and the conservation of timber quality. The “economic” category included studies on economic repercussions and the marketing of timber disturbed by wind. Finally, the category “environment” summarised papers dealing with the environmental impact of the disturbance and secondary damage such as that related to salvage logging and bark beetle outbreaks. Each reference could address one or several topics, as presented in the supplementary material (Table S2).

Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2019) was used to store the key information from the reviewed papers (Table S1) and to facilitate descriptive analysis.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

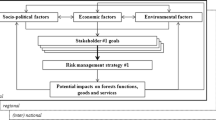

The literature from the six countries covered the four dimensions of post-windthrow management well: strategy (n = 89), operations and safety (n = 73), economy (n = 36) and environment (n = 74) (Fig. 1). Regarding language, 49% of the selected articles were published in English while 17% were in French, 11% in German and 11% in Italian, 10% in Swedish and 3% in Polish. The key topics emerging from the review are presented as a conceptual diagram across spatial and temporal dimensions in Fig. 2. The figure provides an overview on which spatial and temporal scales individual topics are discussed. In other words, when and where do the different activities of windthrow disturbance occur. Topics such as adaptive silviculture, salvage logging and emergency plans, for instance, are usually addressed at the regional level while the marketing of windthrown timber and the response of market prices are topics of national and international concern. A synthesis of the experiences in post-disturbance management is presented in the following sub-sections.

Strategic Aspects of Post-windstorm Management

Across the six focal countries, several common objectives in post-windstorm management emerged, regardless of region or forest type:

-

1. The main priority is the safety of the general population and of forest users and workers engaged in clearing the windthrown trees [16,17,18]. Immediately after a storm event, power lines and roads should be cleared to facilitate the reestablishment of the power supply, to help prevent accidents and enable access for rescue and salvage teams. Injuries and accidents can be avoided by restricting access to disturbed areas. Direct risks that are associated with windthrows (e.g. leaning trees) should be identified, clearly marked (e.g. road closures) and, when necessary, communicated to the public (e.g. via news media).

-

2. The overall extent of the disturbance and the areas affected need to be identified swiftly in order to develop appropriate response strategies [19]. It is essential to estimate (as accurately as possible) the timber volume disturbed as well as to identify the areas affected by the disturbance in order to make decisions how to respond to the event (e.g. processing and marketing of timber). Forest owners should ideally contact the forest administration and inform them of the extent of the disturbance within the first three days after a storm, so that the overall extent of the event can be gauged and measures at the policy level can be considered.

-

3. Measures should be taken to mitigate a disruption of the timber market [17]. It is common for governments to temporarily restrict regular harvesting at the national level after a major windstorm in order to mitigate oversupply. For the same reason, it is recommended that timber disturbed by wind is retained in the forest for as long as possible (if forest health is not negatively affected) and is salvaged only when its utilization by the timber industry is ensured. When windthrown timber must be harvested, high-quality timber should be put on the market first. Adequate storage facilities should be implemented to buffer the market from peaks in timber supply and conserve timber quality. Moreover, stakeholders should negotiate a fair market price after a storm event and set the term of the agreement.

Two more elements emerged from literature review but are only relevant under specific conditions (e.g. in the case of a protective forest or a conservation area):

-

4. The protective effect of a forest against gravitational natural hazards should be maintained or restored as quickly as possible to bridge the “protective gap” after a windstorm. Planting and temporary engineering measures are frequently recommended in areas where the protective function of forests is vital and regeneration is relatively slow, e.g. in mountain forests [20,21,22]. A recommendation for protective forests is to refrain from removing windthrown timber which is still rooted so as to protect against floods and avalanches during the regeneration stage [23, 24].

-

5. Biodiversity must be conserved and promoted [12•, 17, 25•]. Post-disturbance management decisions, such as whether to “salvage” or “not to salvage”, can have long-term consequences on timber markets as well as on forest biodiversity. What constitutes a good approach in this regard remains an intensively discussed question [25•, 26], yet biodiversity often benefits if at least some disturbed trees are retained. Nevertheless, researchers and practitioners agree that this decision is strongly dependent on the main objectives of forest management (e.g. conservation or production) and on the risk of secondary disturbances (e.g. beetle infestation, wildfires, avalanches, etc.) that might affect post-disturbance forest development [14••].

In addition to the above-mentioned objectives, it is essential to prepare emergency plans in advance and define the different roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder to efficiently address future large-scale disturbance events [27]. To that end, amongst other things, a better coordination between the state and local authorities is needed [28].

Operational and Safety Aspects of Post-windstorm Management

Damage Assessment

The first premise of post-windthrow management is to ensure people’s safety. The next important step in responding to a storm event is damage assessment, which should be completed shortly after the storm [17, 19, 29]. The aim of damage assessment is to give an overview of the situation and the extent of the event, providing essential information for strategic decisions regarding immediate action at national and regional levels [17]. It also includes assessing if the available resources such as machinery and workforce are sufficient or whether external help is needed. Foresters can carry out damage assessments through ground-based observations or aerial surveys based on satellite imagery and drone flights [9]. Aerial surveys can be used for strategic planning, whereas tactical planning generally requires direct visits to the affected sites [30, 31].

Salvage Logging and Safety

Salvage logging carries a high risk of accidents due to time pressure, stress, poor weather conditions, entangled trees and damp soils, as well as a limited workforce and resources. The main factors influencing the degree of risk during salvage operations are the level of experience and training of the workers; the operation status and maintenance of the machinery being used, the logging technique and degree of mechanisation; and the coordination between concurrent tasks [17, 32]. Good practice examples for carrying out salvage logging operations and reducing the risk of accidents have been presented recently [18]. One general recommendation is to conduct salvaging operations in a highly mechanised system, using cut-to-length (CTL) technology. Furthermore, it is important to ensure that the machinery used complies with all safety standards, such as laminated safety glass to protect the operator in the cabin, and a positioning system for GPS tracking. Occupational safety can also be supported by electronic devices and software, e.g. delineating accessible areas for machine traffic or providing information on the nearest rescue meeting points [33, 34]. After large-scale storms, formalised routines of decision-making [17, 35] can help to prioritise actions and thus reduce the risk of accidents.

When motor-manual work needs to be performed, at least one machine (commonly crawler excavators with flexible steel tracks and equipped with a grapple or heavy harvester machines) should be on site to support the operation [16]. Motor-manual work should be limited to separating stems from the root plate, while all further processing steps should be performed by a harvester or machinery situated outside the windstorm area, e.g. at a central landing. In steep terrain or on wet soils that are inaccessible to machines, cable yarding systems are recommended. They can support motor-manual work and reduce the risk of accidents. Where a general system of skid roads exists as part of regular forest management (e.g. skid roads every 20 to 40 m), the driving on site is limited also during salvage logging [16]. Moreover, temporary timber landings and roads can be built to ease the mobilisation of timber [19].

Transport and Storage

The effective clearing of windthrown Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst) stands is a delicate balance between a moderate supply of timber to the market to keep timber prices stable and the necessary salvage logging to avoid secondary disturbances (e.g. insect outbreaks). Immediately after tree processing, the logged timber should be transported to the industry for processing, or stored outside the forest to reduce breeding material for bark beetles [36]. However, transportation capacities are often a limiting factor in post-windthrow management. Improved communication between forest managers, machine operators, logistics providers and the timber industry is required to reduce delays. When immediate transportation and processing is not possible, several storage options exist [36], namely: (i) log yards outside the forest (> 500 m from the forest, if bark beetle infestations are of concern), (ii) humidity-controlled storage, (iii) debarking and (iv) the application of pesticides to protect against biotic risks. Humidity-controlled storage facilities (also known as wet storage) represent a promising alternative for the storage of high-quality spruce and pine timber for between 2 and 5 years [16, 37•]. However, they are cost-intensive, time-consuming to initiate and have to fulfil a number of legal regulations (e.g. regarding water quality). Studies show that the application of this storage method generally has low environmental impact, particularly when combined with a system to recover and recycle water [23, 38]. Timber quality does not significantly decrease for a storage duration of less than 3 years for spruce and up to 5 years for pine [16, 23, 37•]. Other species, such as European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.), do however decrease considerably in their quality [39].

Economic Impact of Post-windstorm Management

The management of storm-damaged stands in order to mitigate economic losses is complex and often not intuitive [40]. With pulses of timber entering the market, timber prices drop, while the cost of (salvage) logging greatly increases after a windstorm. Salvage logging after extreme disturbance events is thus often not economically viable [41]. Consequently, there is a low economic motivation for forest owners to salvage and sell timber. An alternative option is the storage of salvaged timber until market prices consolidate, yet storage incurs further costs. Large storm events can lead to the need for additional administrative staff and the purchasing of new machines (harvesters or forwarders). Therefore, financial support for post-disturbance management, e.g. supporting the wet storage of timber and the reforestation of disturbed areas, is crucial.

Environmental Concerns of Post-windstorm Management

There is an ongoing debate about the influence of salvage logging of disturbed sites on biodiversity, stand regeneration and subsequent stand development. Both negative and positive impacts on biodiversity have been reported. The removal of deadwood can reduce the biodiversity of saproxylic species dependent on this resource, and heavy machinery can lead to soil compaction. A recent review showed that harvester-forwarder systems cause less damage to soil, regeneration and residual stands during salvaging operations than a system using skidders or cable yarders for extraction [42••]. Pits and mounds from fallen trees as well as disturbances from salvage logging may have positive effects on seed germination after windthrow, particularly for pioneer species [43•, 44, 45]. But also retained windthrown logs can provide a good germination substrate as they decay [21]. Retaining tree tops and small-diameter trees helps to sustain heliophilous beetle species [46]. In addition, novel debarking approaches (e.g. bark scratching, where only strips of bark are removed to prevent bark beetles from completing a successful brood) can help to support deadwood-dependent populations [47]. Snags (i.e. standing dead trees) can serve as future habitat trees and foster biodiversity. Some authors recommend that forest managers should retain several habitat trees per hectare also after salvage logging—similar to regular harvesting operations—in order to conserve biodiversity [17, 24, 48, 49]. Moreover, scattered windthrows and less severe disturbances offer the opportunity to create conservation islands [50] and increase the structural diversity of ecosystems [51].

Country-Specific Experiences

France

In France, 31% of the land area is covered by forests and three-quarters of the French forests belong to private owners. Forests close to the Atlantic are particularly susceptible to windstorms. After storms Lothar (in the north of the country) and Martin (in the south-west) in 1999, France decided to delay the supply of the timber to the market and spread it out geographically [52]. A commercialisation network for windthrown timber was established to help coordinate harvest, storage and transport operations. As a consequence, the average timber prices did not decrease by more than 35–38%, instead of the 50% that were predicted without such measures [52]. Moreover, stakeholders agreed on the set timber prices to be maintained until supply exceeded demand [52] while a government relief programme offered financial support for clearing disturbed stands, improving road networks and purchasing new machinery [53]. In France, salvage logging after the storms of December 1999 was performed in a hurry and, according to the literature, often with little concern for the impacts on soil and biodiversity [54]. From this experience, a decision was taken that in the future only necessary action would be taken and heavy operations that may increase environmental impact and costs would not be rushed [54, 55]. Long-term wet storage was well established in France after the 1999 storms [23]. According to Hermeline [56], the role of transportation and storage was essential for the preservation of timber value after the windthrows in 1999 [52].

Germany

In Germany, 32% of the land area is covered by forests with an average growing stock of 336 m3 ha−1. Almost half of this forest area is privately owned with predominantly small and fragmented holdings with an average size of below 20 hectares. While no official national strategy exists to promote post-windstorm management, large wind disturbances in the past decades have resulted in a number of projects addressing disturbance management and leading to clear recommendations for practitioners [16, 36]. Specific recommendations have been developed following the emergency management cycle, including management measures for the dimensions preparedness, intervention, recovery and prevention [57]. With regard to salvage logging, one recommendation is to prioritise the tree species most vulnerable to bark beetle infestation, i.e. to first salvage Norway spruce and then other softwoods, leaving deciduous trees to be salvaged last [36]. Furthermore, salvage operations should be prioritised by disturbance size and the expected environmental impact: single trees and small clusters of windthrown trees should be given priority (to be cleared until mid of May after a winter storm), while larger disturbed areas should be managed after that (ideally until the beginning of June, but at least until the next spring) [36]. Practitioners often receive financial or administrative support from the federal forest administrations shortly after a windstorm event, for example, by increasing the admissible total weight for log transportation in the affected area from 40 to 44 t. Moreover, after storm “Kyrill” in 2007, one of the state forest administrations published a handout aiming to minimise the infestation of remaining stands by bark beetles. To store windthrown timber, the mechanical debarking of logs with modified harvester heads was also attempted in Germany: this approach succeeded in reducing the risk of bark beetle infestations and improving transportation efficiency, but also proved costly [58,59,60]. Therefore, instead of complete debarking, bark scratching was suggested as a cost-effective alternative, achieving the same goals at 28% lower cost [61].

Italy

In Italy, 31% of the country is covered by forest, of which 66% is privately owned [62]. The windstorm events experienced in Italy can be categorised according to their frequency and geographical characteristics. In particular, windstorm events can be (1) frequent (endemic) (e.g. typical for littoral stands where windstorms occur almost every winter, [63]), (2) infrequent and small-scale (e.g. in March 2015 in the area of Tuscany, [64]) or (3) infrequent and large scale (e.g. the 2018 storm “Vaia” that hit northeastern Italy [9, 63]). The different scales and characteristics of these three event types imply different post-disturbance management. Endemic disturbances are generally managed locally by small-scale contractors [65]. In contrast, local firms are usually not able to cope with large-scale disturbances and help must be sought from neighbouring regions and countries [66]. The challenges of massive and rapid salvage operations have favoured the application of mechanised harvesting technology among Italian logging companies [67]. However, limited investment capacity, uncertainty about future use and terrain constraints hamper the country’s mechanisation progress [68]. Before the latest windthrow event in 2018, the mechanization of salvage operations was introduced mainly to littoral stands in central Italy, where wind damage is frequent and favourable terrain conditions facilitate the use of machines [65, 69]. Because of the high costs of storage—and the limited availability of suitable storage sites—Italian experts estimate that only 5 to 10% of the total windthrown timber volume can be effectively stored [70].

Poland

Forests in Poland (30% of the land area) are mainly managed by the state forest administration, which is responsible for 77% of the total forest area [71], while the remaining areas are public (3.8%) and private (19.3%) forests. Therefore, when a large storm event occurs, the state forest administration takes most of the decisions. Cut-to-length (CTL) technology is a popular system and is used in the harvesting of ca. 40% of timber in Poland [71, 72]. It is recommended for post-windthrow salvage logging [73,74,75] because of considerations of work safety and efficiency. Motor-manual and chainsaw-based operations may also be used for clearing windthrown areas, as combined approaches where trees are separated from the stump with a chainsaw before being processed by a harvester [76]. When CTL-technology is used for clearing disturbed areas, lower productivity can be expected compared to conventional operations [74, 77] leading to higher harvesting costs [78,79,80,81]. Extra costs can occur when stumps have to be removed [82] after windthrow or when broadleaved species are processed due to difficulties in delimbing [83] and challenges of keeping accurate lengths [80]. Uncleared windthrow of Norway spruce can provide breeding material for insects and may therefore trigger outbreaks of bark beetles [84, 85]. Data concerning spruce stands in the Tatra Mountains (Tatra National Park) showed that, in the last century, bark beetle outbreaks followed all major wind or snow disturbances. However, infestations were avoided or contained when timber was salvaged [86] as, for example in the summer of 1963 in the Tatra Mountains, after the clearing of timber previously damaged by snow [84].

Sweden

Sweden is dominated by forests (69% of the land area), most of which are privately owned (72% of the forest area) [87]. Swedish forest policy is characterised by “freedom with responsibility” and the forest sector is based on free-market mechanisms. Windstorm events are frequent in the country, and despite the absence of an official post-windstorm strategy, guidelines are available on how to proceed after a windstorm [88]. After storm “Gudrun” in 2005, the Swedish Forest Agency’s overall assessment was that the forest industry’s performance in post-windthrow management had been excellent, despite the severity of the damage [89, 90]. The processing and handling of the timber disturbed by wind proceeded better than expected, thanks to the active participation of forest owners and the good communication between actors and authorities [91]. Moreover, a study showed that, after 10 years, the forest area affected by storm Gudrun had almost recovered its pre-storm conditions, suggesting that foresters had made good choices when aiming to restore the forest area [92•]. Generally, the state does not give subsidies to forest owners affected by windstorms [92•]. Yet, the government made an exception for Gudrun and, with the help of the EU, provided a financial support package of more than 3 billion Swedish crowns (corresponding to approx. 300 million euros). This included a tax reduction for storm-damaged timber, a diesel tax exemption, reforestation support, road support, storage support and abolished track and fairway fees [91]. Storm “Gudrun” also highlighted the importance of risk management awareness in forestry practices [93]. Indeed, many forest owners had no insurance against wind damage prior to the event in 2005 [7].

Switzerland

Swiss forests cover one-third of the country, are mainly owned by the public (ca. 70%) and extend across a wide range of topographies, from lowlands to mountainous regions, forcing managers to adapt their logging practices and post-windstorm management accordingly. Taking stock of the lessons learned from storms “Vivian” (1990, in the mountainous regions) and “Lothar” (1999, in the lowlands), the Swiss government published an official handbook in 2008 to advise foresters and other actors affected by storm disturbances [17]. Surveys showed a lower rate of accidents after “Lothar” compared to “Vivian”, as salvage logging was mainly mechanised and was performed in the lowlands [94, 95]. The Swiss timber industry was only able to process a fraction of the large quantities of timber salvaged from these two wind disturbance events due to insufficient transportation capacities, which resulted in a loss of timber quality [17]. As a result, high volumes of deadwood were left in the forest, averaging 275 m3 ha−1 for both storms [96], and thus considerably exceeding the minimum deadwood volumes proposed by Müller and Bütler [97] in a conservation context (20–50 m3 ha−1). A total of 49% of the Swiss forests are defined as protective forests against natural hazards, such as avalanches and rockfall, which highlights the importance of quickly recovering the functions of these forests after a storm event [17, 22]. Studies showed that at least 20 to 30 years are needed to restore the protective function after wind disturbance [20, 44, 98].

Outlook

Choosing between “clearing” and “keeping” windthrown timber after a storm event remains an intensively discussed question as this post-disturbance management decision has long-term consequences for timber markets, forest biodiversity and other ecosystem goods and services. The strategies applied in post-windthrow management need to be adapted to local conditions such as the severity of the disturbance, the growing stock and age of the disturbed stand and its accessibility. Yet, three commonly adopted strategies for post-windthrow management in Europe emerging from our review are (1) clearing, including windthrown trees and standing survivors, (2) salvaging a fraction of the windthrown timber but leaving standing trees and retaining some dead trees on site or (3) not salvaging at all [26]. Which post-disturbance management strategy is chosen strongly depends on the legal framework, but also on the type of forest, its topography and vulnerability to other disturbances, the resource availability to clear a site, as well as the prioritisation of management goals (e.g. production forest vs. high conservation value forest). The countries investigated here differed in their management response to windthrow, with differences being explained, in part, by various management objectives. Swiss forests, for instance, are managed for multiple uses and have a strong protective function against natural hazards, while roundwood production is the primary objective in a significant fraction of Swedish forests. These differences are reflected in national legislation for timber harvesting and biodiversity conservation, which inter alia guided decisions regarding salvage logging. Moreover, the further pathways of salvaged timber differed among countries. Long-term wet storage is well established in France, while in Germany also mechanical debarking of logs was adopted to address the storage needs in the context of pulses of disturbed timber. In Italy, the limited investment capacity in forestry also resulted in limited storage of windthrown timber (e.g. 5–10% of the total volume salvaged can be stored). Limited transport and storage capacities in Switzerland (e.g., compared to France) led to large amounts of timber being left on site. In Sweden, the forest legislation prohibits the storage of freshly felled roundwood in the forest and along forest roads during summer; thus, timber storage mostly takes place in mills. In Poland, large shares of windthrow timber are salvage logged while planned harvesting is put on standby to avoid a timber surplus on the market.

The ecological consequences of salvage logging remain unclear and are the subject of ongoing policy debates [14••, 99]. One consequence of salvage logging is the removal of disturbance legacies (i.e. the remaining structures of the original forest, which includes standing and downed dead wood, live trees and seed banks; [100]). There is increasing evidence of the role of biological legacies in forest resilience [21, 101], providing seed sources and substrate for the regeneration after disturbance and creating habitat for a wide range of species [97]. Moreover, not removing logs after a storm can temporarily protect against natural hazards (e.g. rockfall and avalanches) during a period in which the regenerating forest cannot fulfil its protective role [22]. However, it is not clear to which extent retaining disturbance legacies is in conflict with forest management for other ecosystem services such as provisioning (e.g. food and wood production), regulating (e.g. climate regulation) and cultural services (e.g. recreation) [102••]. Future research should thus focus on how to better include disturbance legacies in multifunctional forest management [102••]. Thorn et al. [25•] found that 75% of a disturbed area needs to be left unlogged to maintain 90% of its species richness. Consequently, more research is needed on how to manage deadwood (e.g. amount and spatial–temporal distribution) to promote forest recovery and biodiversity without compromising the economy of forest management or increasing the risk of secondary disturbances (e.g. wildfires or bark beetle outbreaks [12•],).

Storm events in Norway spruce forests often trigger bark beetle outbreaks [103] and can make forests more vulnerable to further wind damage [104] or other natural disturbances such as drought and wildfires [105]. Clearing windthrown areas is recognised as one of the most effective control measures for bark beetle (Ips typographus (L.)) outbreaks [85]. However, the efficiency of salvage logging for dampening bark beetle outbreaks is greatly reduced by climate change and salvage logging might not be able to prevent a climate-related intensification of bark beetle infestations (i.e. resulting from an increasing reproduction rate and decreasing winter mortality) [99]. Furthermore, not clearing windthrow in some parts of the landscape (e.g. because of conservation goals) does not seem to negatively impact the rest of the landscape [106]. Different post-disturbance management strategies thus can be applied at the landscape scale, yet need to consider successive interacting disturbances [102••]. This is particularly important in the context of climate change which will most likely amplify both the individual and combined impact of interactive natural disturbances [3]. In this regard, it is also important to note that disturbances such as major storms can be important drivers of changes in forest ecosystems and can facilitate their adaptation to climate change [107, 108]. To better quantify the potential of disturbances to facilitate adaptation, long-term data is required. Existing field experiments should thus be maintained to monitor the effects of different post-disturbance management strategies and how these affect forests resilience.

Stand regeneration is influenced significantly by post-windstorm management. Notable differences in succession have been observed for cleared and uncleared stands [109]. A current debate in European forest management is about whether to replant disturbed areas or not, with what species and where. Studies showed that advanced regeneration (i.e. saplings) can accelerate regeneration after a storm event, particularly at high elevations [20, 44, 98]. Natural regeneration should be promoted [17], but sometimes this process is slow. This is especially the case at high elevations, where forests often fulfil a protective function, e.g. against avalanches and rockfall. In these instances, planting is an important tool to quickly restore the protective function of the forest. Planted species should be adapted to local site conditions, and mixed species stands should be promoted to diminish the risk of future disturbances [17, 95, 110, 111]. A higher proportion of broadleaved tree species or wind-firm conifers (e.g. silver fir, Abies alba Mill) can reduce the vulnerability to wind of monospecific Norway spruce stands by a factor of three [110]. More broadly, the choice of species to be planted after a windstorm should consider (1) vulnerability to future storm events, (2) demanded products and services and (3) resistance and resilience to climate change.

A recent global meta-analysis concluded that the degree of salvage logging should be defined on a large scale (e.g. regional policy and management plants) while considering local variations such as climate, topography and species compositions [14••]. This meta-analysis also suggested targeting specific management goals rather than aiming to address all potential ecosystem services in post-disturbance management [14••]. A diversification of management strategies in space (i.e., zoning approaches) may be a potential solution for reducing trade-offs between management objectives. Changes in drought periods put more stress on regeneration but changes in soil frost, snow cover and tree species composition also make forest operations more difficult [112, 113]. These aspects underline the global change is posing considerable challenges for post-disturbance management.

We conclude that general recommendations regarding post-disturbance management need to be adjusted and tailored to each situation and context. Salvage logging might be essential in forests susceptible to bark beetle outbreaks while no salvage logging is recommended in protective forests and forests of high conservation value. Moreover, decisions on salvage logging will depend strongly on the amount of windthrown timber sawmills are able and willing to process, highlighting the importance of storage capacities (which vary by country) and timber prices (affected by the international market). We here suggest an integrative approach to post-disturbance management that considers strategic, operational, economic and ecological dimensions. A further important aspect is to align short-term operational considerations and long-term strategic goals. This can, however, only be achieved by an increased understanding of natural disturbances by the general public and support at the policy level. Remaining research gaps that should be tackled in future studies include (1) how to strike a balance between the positive and negative effects of salvage logging, (2) how to integrate climate change considerations more explicitly in post-windthrow management and (3) how to plan post-disturbance management in interactive disturbance regimes (e.g. with disturbances from bark beetles, windthrow and drought) rather than focusing on individual disturbance agents.

Change history

14 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Gardiner B, Blennow K, Carnus J, Fleischer P, Ingemarson F, Landmann G, et al. Destructive storms in European forests: past and forthcoming impacts. Final Rep to Eur Comm - DG Environ. 2010;138.

Senf C, Seidl R. Storm and fire disturbances in Europe: Distribution and trends. Glob Change Biol. 2021;27:3605–19.

Seidl R, Thom D, Kautz M, Martin-Benito D, Peltoniemi M, Vacchiano G, et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nat Clim Chang. 2017;7:395–402.

Pischedda D, Stodafor. Technical guide on harvesting and conservation of storm damaged timber [Internet]. Centre technique du bois et de l’ameublement; 2004. Available from: https://books.google.ch/books?id=n1oQv9ghOSkCAccessed 5 July 2020

Fink AH, Brücher T, Ermert V, Krüger A, Pinto JG. The European storm Kyrill in January 2007: Synoptic evolution, meteorological impacts and some considerations with respect to climate change. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2009

Valinger E, Fridman J. Factors affecting the probability of windthrow at stand level as a result of Gudrun winter storm in southern Sweden. For Ecol Manage. 2011;262:398–403.

Valinger E, Kempe G, Fridman J. Forest management and forest state in southern Sweden before and after the impact of storm Gudrun in the winter of 2005. Scand J For Res. 2014;29:466–72.

Taszarek M, Pilguj N, Orlikowski J, Surowiecki A, Walczakiewicz S, Pilorz W, et al. Derecho evolving from a Mesocyclone-A Study of 11 August 2017 severe weather outbreak in Poland: Event analysis and high-resolution simulation. Mon Weather Rev. 2019;147:2283–306.

Chirici G, Giannetti F, Travaglini D, Nocentini S, Francini S, D’Amico G, et al. Stima dei danni della tempesta “Vaia” alle foreste in Italia [Forest damage inventory after the “Vaia” storm in Italy ]. For - Riv di Selvic ed Ecol For. 2019;16:3–9.

Motta R, Ascoli D, Corona P, Marchetti M, Vacchiano G. Selvicoltura e schianti da vento. Il caso della tempesta “Vaia” [Silviculture and wind damages. The storm “Vaia”]. For - Riv di Selvic ed Ecol For. 2018;15:94–8.

XWS Datasets. Extreme Wind Storms Catalogue [Internet]. Met Off. Univ. Read. Univ. Exet. under Creat. Commons CC BY 4.0 Int. Licence. 2020. Available from: http://www.europeanwindstorms.org/cgi-bin/storms/storms.cgi?storm1=XynthiaAccessed 11 April 2021

• Thorn S, Bässler C, Brandl R, Burton PJ, Cahall R, Campbell JL, et al. Impacts of salvage logging on biodiversity: a meta-analysis. J Appl Ecol. 2018;55:279–89. This paper is a meta-analysis on the effects of salvage logging on biodiversity. It concludes with the need of future research to assess the amount and spatio-temporal distribution of retained dead wood needed to conserve biodiversity.

•• Leverkus AB, Lindenmayer DB, Thorn S, Gustafsson L. Salvage logging in the world’s forests: interactions between natural disturbance and logging need recognition. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2018; This systematic review reveals that most studies on salvage logging are not able to test interactions between natural disturbance and logging. It concludes that disentangling the pathways producing disturbance interactions is crucial to guide management and policy regarding naturally disturbed forests.

•• Leverkus AB, Gustafsson L, Lindenmayer DB, Castro J, Rey Benayas JM, Ranius T, et al. Salvage logging effects on regulating ecosystem services and fuel loads. Front Ecol Environ. 2020;18:391–400. This global meta-analysis reveals that salvage logging has a negative effect on regulating ecosystem services (e.g. regulation of water conditions and soil quality). However, as individual studies on salvage logging report variable effects; management can be adjusted to address case-specific ecological conditions and management goals.

Torgerson C. Systematic Reviews. A&C Black. 2003.

Odenthal-Kahabka. Handraichur Sturmschadenbewältigung. [Internet]. Landesforstverwaltung Baden-württemb. und Landesforsten Rheinland-Pflaz. 2005 [cited 2020 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.waldwissen.net/de/technik-und-planung/forsttechnik-und-holzemte/waldarbeit/arbeitsverfahren-im-sturmholzAccessed 5 July 2020

OFEV. Aide-mémoire en cas de dégâts de tempête. Aide à l’exécution pour la maîtrise des dégâts dus à des tempêtes en forêt classées d’importance nationale [Storm damage handbook. Implementation aid for dealing with storm damage events of national importance in. Bern; 2008.

SUVA. Sécurité lors de l’exploitation des chablis! [Safety during operation windfall!] [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.suva.ch/de-CH/material/Dokumentationen/sturmholz-sicher-aufruesten-44070d2375223752Accessed 6 July 2020

Tomaszewski K. Decision 211 by Director General of the State Forests from 11 August 2017 – in order to specify extraordinary procedure due to windbreaks on the areas of the State Forests taking place on 11 and 12 August 2017. Warszawa, DGLP; 2017.

Schönenberger W. Post windthrow stand regeneration in Swiss mountain forests: the first ten years after the 1990 storm Vivian. For Snow Landsc Res. 2002;77:61–80.

Rammig A, Fahse L, Bebi P, Bugmann H. Wind disturbance in mountain forests: simulating the impact of management strategies, seed supply, and ungulate browsing on forest succession. For Ecol Manage. 2007;242:142–54.

Wohlgemuth T, Schwitter R, Bebi P, Sutter F, Brang P. Post-windthrow management in protection forests of the Swiss Alps. Eur J For Res. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2017;136:1029–40.

Flot J-L, Vautherin P. Des stocks de bois à conserver en forêt ou hors forêt [Timber stocks to be stored in forests or elsewhere]. Rev For Française. 2002;54:136–44.

Gosselin M, Paillet Y. Mieux intégrer la biodiversité dans la gestion forestière. Guide pratique. Quae E, editor. 2010; p 156.

• Thorn S, Chao A, Georgiev KB, Müller J, Bässler C, Campbell JL, et al. Estimating retention benchmarks for salvage logging to protect biodiversity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–8. This is the first scientific article that has estimated a retention benchmark to protect biodiversity during salvage logging. They estimated that 75% of a naturally disturbed area of a forests needs to be left unlogged to maintain 90% richness of its unique species, whereas retaining 50% maintains 73%.

Petucco C, Andrés-Domenech P, Duband L. Cut or keep: what should a forest owner do after a windthrow? For Ecol Manage. 2020;461:117866.

Drouineau S, Laroussinie O, Birot Y, Tettrasson D, Formery T, Roman-Amat B. Expertise collective sur les tempêtes, la sensibilité des forêts et sur leur reconstitution [Collective expertise on storms, the sensitivity of forests and on their reconstitution]. Courr l’environnement l’INRA. 2000;57–77.

Rosenberg P-E, Barthod C, Barrillon A. Conclusion en forme de premières réflexions [Conclusion in the form of early reflections]. Rev For Française [Internet]. 2002; Available from: http://documents.irevues.inist.fr/bitstream/handle/2042/4988/217_223.pdf?sequence=1Accessed 11 April 2021

Hycza T, Ciesielski M, Zasada M, Bałazy R. Application of Black-Bridge Satellite Imagery for the Spatial Distribution of Salvage Cutting in Stands Damaged by Wind. Croat J For Eng. 2019;40:125–38.

Chirici G, Bottalico F, Giannetti F, Del Perugia B, Travaglini D, Nocentini S, et al. Assessing forest windthrow damage using single-date, post-event airborne laser scanning data. Forestry. 2018;91:27–37.

Zanrosso C, Lingua E, Pirotti F. GS. Progetto InForTRac: innovazione e gestione forestale anche a seguito di Vaia [InForTRac project: innovation and forest management also following Vaia]. Sherwood For e Alberi Oggi. 2019;243:29–32.

Danguy des Déserts D, Bigot M, Cacot E, Gérard S, Collet F, Estève L. Exploitation des chablis: attention danger! [Salvage logging: Warning danger!]. Rev. For. Fr. 2002.

Picchio R, Latterini F, Mederski PS, Venanzi R, Karaszewski Z, Bembenek M, et al. Comparing accuracy of three methods based on the gis environment for determining winching areas. Electron. 2019;8:53.

Picchio R, Latterini F, Mederski PS, Tocci D, Venanzi R, Stefanoni W, et al. Applications of GIS-based software to improve the sustainability of a forwarding operation in central Italy. Sustain. 2020;12:5716.

Forster B, Meier F. Sturm, Witterung und Borkenkäfer: Risikomanagment im Forstschutz. [Storm. Wheather and bark beetles. Risk management in forest protection]. Eidg Forschungsanstalt WSL. 2008;44.

Huber S, Gößwein S, Bork K. Zeitnahe Aufarbeitung des Sturmholzes minimiert Folgeschäden durch Borkenkäfer - Blickpunkt Waldschutz [Timely processing of storm wood minimizes consequential damage from bark beetles - focus on forest protection]. Bayer Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft [Bavarian State Inst For For [Internet]. 2020; Available from: http://www.lwf.bayern.de/waldschutz/monitoring/241397/index.phpAccessed 11 April 2021

• Zimmermann K, Schuetz T, Weimar H. Analysis and modelling of timber storage accumulation after severe storm events in Germany. Eur J For Res. 2018;137:463–75. This paper explored the determinants of forest enterprises’ timber storage accumulation after severe storm events. r central fnding of our study is that the timber price drops after storm events act as a moderator variable on the relation between damaged and stored timber quantities.

Moreau J, Chantre G, Vautherin P, Gorget Y, Ducray P, Leon P. Conservation de bois sous aspersion [Wood storage under misting systems]. Rev For Française. 2006;58:377–87.

SIA. Dauerhaftigkeit von Holz und Holzprodukten - Prüfung und Klassifikation der Dauerhaftigkeit von Holz und Holzprodukten gegen biologischen Angriff [Durability of wood and wood products - testing and classification of the durability of wood and wood product. 2016.

Deegen P, Matolepszy K. Economic balancing of forest management under storm risk, the case of the Ore Mountains (Germany). J For Econ. 2015;21:1–13.

Knoke T, Gosling E, Thom D, Chreptun C, Rammig A, Seidl R. Economic losses from natural disturbances in Norway spruce forests–A quantification using Monte-Carlo simulations. Ecol Econ. 2021;185:107046.

•• Picchio R, Mederski PS, Tavankar F. How and how much, do harvesting activities affect forest soil, regeneration and stands? Curr For Reports. 2020;6:115–28. This review identifies the state of the art in forest utilisation, identifying how and how much forest operations affect forest soil, regeneration and the remaining stand. It concludes that a decrease in damage is possible by optimising skid trail and strip road planning, careful completion of forest operations and training for operators.

• Leverkus AB, Rey Benayas JM, Castro J, Boucher D, Brewer S, Collins BM, et al. Salvage logging effects on regulating and supporting ecosystem services — a systematic map. Can J For Res. 2018;48:983–1000. This paper has developed a systematic map to provide an overview of the primary sources studying the effects of salvage logging on regulating and supporting ecosystems services and created a database with the retrieved publications.

Wohlgemuth T, Kull P, Wüthrich H. Disturbance of microsites and early tree regeneration after windthrow in Swiss mountain forests due to the winter storm Vivian 1990. For Snow Landsc Res. 2002;77:17–47.

Kramer K, Brang P, Bachofen H, Bugmann H, Wohlgemuth T. Site factors are more important than salvage logging for tree regeneration after wind disturbance in Central European forests. For Ecol Manage. 2014;331:116–28.

Thorn S, Bässler C, Gottschalk T, Hothorn T, Bussler H, Raffa K, et al. New insights into the consequences of post-windthrow salvage logging revealed by functional structure of saproxylic beetles assemblages. PLoS One. 2014;9.

Hagge J, Leibl F, Müller J, Plechinger M, Soutinho JG, Thorn S. Reconciling pest control, nature conservation, and recreation in coniferous forests. Conserv Lett. 2019;1–8.

Werner SAB, Müller J, Heurich M, Thorn S. Natural regeneration determines wintering bird presence in wind-damaged coniferous forest stands independent of postdisturbance logging. Can J For Res. 2015;45:1232–7.

Thorn S, Werner SAB, Wohlfahrt J, Bässler C, Seibold S, Quillfeldt P, et al. Response of bird assemblages to windstorm and salvage logging - Insights from analyses of functional guild and indicator species. Ecol Indic. 2016;65:142–8.

Mao B. Tempête Klaus : quel impact écologique ? [Klaus storm: what is the ecological impact?]. GEO [Internet]. 2012; Available from: https://www.geo.fr/environnement/tempete-klaus-33104

Senf C, Mori AS, Müller J, Seidl R. The response of canopy height diversity to natural disturbances in two temperate forest landscapes. Landsc Ecol. 2020;35:2101–12.

Badré M. La commercialisation des chablis dans les forêts publiques: résultats et enseignements [Marketing of State Forest Windthrows - Some Innovative Methods]. Rev For Française. 2002;54:94–102.

Barthod C, Barrillon A. L’état au secours de la forêt: le plan gouvernemental[Government support for forests: the government relief program]. Rev For Française. 2002;54:41–65.

Vallauri D. Restoring forests after violent storms. For. Restor. Landscapes Beyond Plant. Trees. 2005.

Mortier F, Rey B. L’Office National des Forêts guide la reconstitution des forêts publiques [The Office National des Forêts leads the Way in State Forest Reforestation]. Rev Bois Forêts des Trop. 2002;54:190–203.

Hermeline M. Le rôle essentiel du transport dans la valorisation des bois [The essential role of transportation in maximising timber value]. Rev For Française. 2002;54:123–35.

Tillmann F, Aaron W. Der 4–3–2-Krisenmanagement-Zyklus [Internet]. Waldwissen. 2019. Available from: https://www.waldwissen.net/de/waldwirtschaft/schadensmanagement/praeventivmassnahmen-bei-krisen-mit-schadpotential

Hauck A, Pruem H-J. Debarking Head im Hunsrück - Vollmechanisierte Holzernte bei gleichzeitiger Entrindung [Debarking Head in the Hunsrueck - Fully mechanized Harvesting Operations with Simultaneous Debarking]. Forsttechnische Informationen (FTI). 2019;71:14–5.

Heppelmann JB, Labelle ER, Wittkopf S. Static and sliding frictions of roundwood exposed to different levels of processing and their impact on transportation logistics. Forests. 2019;10:1–18.

Bennemann, C., Heppelmann, J.B., Wittkopf, S., Hauck, A., Grünberger, J., Heinrich, B., Seeling U. Debarking Heads. LWF aktuell. 2021;44–6.

Thorn S, Bässler C, Bußler H, Lindenmayer DB, Schmidt S, Seibold S, et al. Bark-scratching of storm-felled trees preserves biodiversity at lower economic costs compared to debarking. For Ecol Manage. 2016;364:10–6.

Mongabay. Italy Forest Information and Data [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/deforestation/2000/Italy.htm

Cantiani MG, Scotti R. Le fustaie coetanee di pino domestico del litorale tirrenico: studi sulla dinamica di accrescimento in funzione di alcune ipotesi selvicolturali alternative [The contemporary stone pine forests of the Tyrrhenian coast: studies on the growth dynamics as a. Ann dell’Istituto Sper per l’Assestamento For e per l’Alpicoltura. 1988;11:1–54.

AA.VV. Stima dei danni da vento ai soprassuoli forestali in Regione Toscana a seguito dell’evento del 5 Marzo 2015 [Estimation of wind damage to forest stands in the Tuscany Region following the event of March 5, 2015]. LAMMA, CFS, Accad Ital di Sci For BURT 49 del 09/12/2015. 2015;

Magagnotti N, Picchi G, Spinelli R. A versatile machine system for salvaging small-scale forest windthrow. Biosyst Eng. 2013;115:381–8.

AA.VV. Piano d’azione Vaia in Trentino: L’evento, gli interventi, i risultati [Vaia Action Plan in Trentino. The event, the interventions, the results]. Prov Auton di Trento. 2020;72.

Marchi E, Magagnotti N, Berretti L, Neri F, Spinelli R. Comparing terrain and roadside chipping in mediterranean pine salvage cuts. Croat J For Eng. 2011;32:587–98.

Spinelli R, Magagnotti N, Jessup E, Soucy M. Perspectives and challenges of logging enterprises in the Italian Alps. For Policy Econ. 2017;80:44–51.

Kleibl M, Klvač R, Lombardini C, Porhaly J, Spinelli R. Soil compaction and recovery after mechanized final felling of Italian coastal pine plantations. Croat J For Eng. 2014;35:63–71.

Fioravanti M, Zanuttini R. Strategie di conservazione del legname abbattuto da tempeste di vento. l’italia For e Mont. 2019

Mederski PS, Borz SA, Đuka A, Lazdiņš A. Challenges in Forestry and Forest Engineering. Croat J For Eng. 2021;42:117–34.

Mederski PS, Karaszewski Z, Rosińska M, Bembenek M. Dynamika zmian liczby harwesterów w Polsce oraz czynniki determinujące ich występowanie [Dynamics of harvester fleet change in Poland and factors determining machine occurrence]. Sylwan. 2016;160:795–804.

Szewczyk G. Variability of the harvester operation time in thinning and windblow areas. Technol Ergon Serv Mod For. Starzyk RJ. Kraków: Publishing House of the University of Agriculture in Krakow; 2011; p. 183–196.

Szewczyk G, Sowa JM, Grzebieniowski W, Kormanek M, Kulak D, Stańczykiewicz A. Sequencing of harvester work during standard cuttings and in areas with windbreaks. Silva Fenn. 2014;48:1159. 16 p.

Giefing DF. Użytkowanie lasu w drzewostanach poklęskowych [Forest utilisation in stands after natural disaster]. Poznań: PULS Press; 2015.

Brzózko J, Kaluga T. Investigations on technological process of after-calamity site preparation to logging with the harvester. Ann Warsaw Univ Life Sci – SGGW, Agric. 2010;56:79–87.

Brzózko J, Szereszewiec B, Elżbieta Szereszewiec. Productivity of machine timber harvesting at the wind-damaged site. Ann Warsaw Univ Life Sci – SGGW, Agric. 2009;54:41–9.

Mederski PS. A comparison of harvesting productivity and costs in thinning operations with and without midfield. For Ecol Manage. 2006;224:286–96.

Mederski PS, Bembenek M, Karaszewski Z, Łacka A, Szczepańska-Álvarez A, Rosińska M. Estimating and modelling harvester productivity in pine stands of different ages, densities and thinning intensities. Croat J For Eng. 2016;37:27–36.

Mederski PS, Bembenek M, Karaszewski Z, Pilarek Z, Łacka A. Investigation of log length accuracy and harvester efficiency in processing of Oak trees. Croat J For Eng. 2018;39:173–81.

Magagnotti N, Spinelli R, Kärhä K, Mederski PS. Multi-tree cut-to-length harvesting of short-rotation poplar plantations. Eur J For Res. 2021;140:345–54.

Laitila J, Poikela A, Ovaskainen H, Väätäinen K. Novel extracting methods for conifer stumps. Int J For Eng. 2019;30:56–65.

Bembenek M, Mederski PS, Karaszewski Z, Łacka A, Grzywiński W, Węgiel A, et al. Length accuracy of logs from birch and aspen harvested in thinning operations. Turkish J Agric For. 2015;39:845–50.

Grodzki W, Guzik M. Wiatro- i śniegołomy oraz gradacje kornika drukarza w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym na przestrzeni ostatnich 100 lat. Próba charakterystyki przestrzennej [Windbreaks, snowbreaks and outbreaks of bark beetle in Tatra National Park in the last 100 years. Spatial characteristic.]. In: Guzik M. (Ed.), Długookresowe zmiany w przyrodzie i użytkowaniu TPN. Tatra National Park Press; 2009; p. 33–46.

Nikolov C, Konôpka B, Kajba M, Galko J, Kunca A, Janský L. Post-disaster forest management and bark beetle outbreak in tatra national park, slovakia. Mt Res Dev. 2014

Grodzki W, Fronek WG. Occurrence of Ips typographus (L.) after wind damage in the Kościeliska Valley of the Tatra National Park. For Res Pap. 2017;78:113–9.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Agriculture and Forestry. Forests and forestry in Sweden. GeoJournal. 2015;24:432.

Skogsstyrelsen. Swedish Forest Agency. 2020.

Klasson A. Tio skogsägares erfarenheter av stormen Gudrun [Ten forest owners’ experiences of storm Gudrun]. 2005.

Fridh M. Stormen 2005 - en skoglig analys. Meddelande 1 - 2006 [Stormen 2005 - a forest analysis. Message 1 - 2006 ]. Skoggstyrelsen [Internet]. 2006;208. Available from: ISSN 1100–0295

Svensson SA, Bohlin F, Bäcke J-O, Hultaker O, Ingemarson F, Karlsson S, et al. Ekonomiska och sociala konsekvenser i skogsbruket av stormen Gudrun [Economic and social consequences of the storm Gudrun on forestry ] [Internet]. Jönköping; 2006. Available from: www.skogsstyrelsen.se

• Valinger E, Kempe G, Fridman J. Impacts on forest management and forest state in southern Sweden 10 years after the storm Gudrun. For An Int J For Res. 2019;92:481–9. This study assessed how the Gudrun Forest area recovered ten years after the storm. The affected area presented almost the same condition prior the storm, meaning that forest owners and managers took rational choices when aiming to restore the disturbed forest.

Blennow K, Olofsson E. The probability of wind damage in forestry under a changed wind climate. Clim Change. 2008;87:347–60.

Raetz P (Bundesamt für UW und L. Erkenntnisse aus der Sturmschadenbewältigung. Synthese des Lothar-Grundlagenprogramms [Findings from storm disturbance management. Synthesis of the Lothar general program]. Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft. 2004;86.

WSL, BUWAL. Lothar. Der Orkan 1999. Ereignisanalyse [Lothar. The hurricane 1999. Event analysis]. Eidg. Forschungsanstalt WSL, Bundesamt für Umwelt, Wald und Landschaft BUWAL. Birmensdorf, Bern; 2001.

Wohlgemuth T, Kramer K. Waldverjüngung und Totholz in Sturmflächen 10 Jahre nach Lothar und 20 Jahre nach Vivian. Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Forstwes. 2015;

Müller J, Bütler R. A review of habitat thresholds for dead wood: a baseline for management recommendations in European forests. Eur J For Res. 2010;129:981–92.

Schwitter R, Sandri A, Bebi P, Wohlgemuth T, Brang P. Lehren aus Vivian für den Gebirgswald - im Hinblick auf den nächsten Sturm [Lessons from Vivian for mountain forests - regarding the next storm]. Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Forstwes. 2015;3:159–67.

Dobor L, Hlásny T, Rammer W, Zimová S, Barka I, Seidl R. Is salvage logging effectively dampening bark beetle outbreaks and preserving forest carbon stocks? J Appl Ecol. 2020;57:67–76.

Johnstone JF, Allen CD, Franklin JF, Frelich LE, Harvey BJ, Higuera PE, et al. Changing disturbance regimes, ecological memory, and forest resilience. Front Ecol Environ. 2016;14:369–78.

Leverkus AB, Gustafsson L, Rey Benayas JM, Castro J. Does post-disturbance salvage logging affect the provision of ecosystem services? A systematic review protocol. Environ Evid. BioMed Central; 2015;4.

•• Taeroe A, de Koning JHC, Löf M, Tolvanen A, Heiðarsson L, Raulund-Rasmussen K. Recovery of temperate and boreal forests after windthrow and the impacts of salvage logging. A quantitative review. For Ecol Manage. 2019;446:304–16. This quantitative review has investigated the recovery processes in forests severely damaged by windthrow. The conclude that there is a lack of research on how disturbance should be managed and to which degree it conflicts with other ecosystem services such as wood production and recreation.

Marini L, Økland B, Jönsson AM, Bentz B, Carroll A, Forster B, et al. Climate drivers of bark beetle outbreak dynamics in Norway spruce forests. Ecography (Cop). Wiley Online Library; 2017;40:1426–35.

Mezei P, Grodzki W, Blaženec M, Jakuš R. Factors influencing the wind-bark beetles’ disturbance system in the course of an Ips typographus outbreak in the Tatra Mountains. For Ecol Manage. 2014;312:67–77.

Kolb, Thomas, et al. "Drought-mediated changes in tree physiological processes weaken tree defenses to bark beetle attack." Journal of chemical ecology; 2019; 45.10: 888–900.

Dobor L, Hlásny T, Rammer W, Zimová S, Barka I, Seidl R. Spatial configuration matters when removing windfelled trees to manage bark beetle disturbances in Central European forest landscapes. J Environ Manage. 2020;254:109792.

Seidl R, Aggestam F, Rammer W, Blennow K, Wolfslehner B. The sensitivity of current and future forest managers to climate-induced changes in ecological processes. Ambio. 2016;45:430–41.

Thom D, Rammer W, Seidl R. Disturbances catalyze the adaptation of forest ecosystems to changing climate conditions. Glob Chang Biol. 2017;23:269–82.

Fischer A, Fischer HS. Individual-based analysis of tree establishment and forest stand development within 25 years after wind throw. Eur J For Res. 2012;131:493–501.

Dvorak L, Bachmann P, Mandallaz D. Sturmschäden in ungleichförmigen Beständen [Storm damage in uneven stands]. Schweiz Z Forstwes. 2001;152:445–52.

Schütz J, Götz M, Schmid W, Mandallaz D. Vulnerability of spruce ( Picea abies ) and beech ( Fagus sylvatica ) forest stands to storms and consequences for silviculture. Eur J For Res. 2006;125:291–302.

Kellomäki S, Maajärvi M, Strandman H, Kilpeläinen A, Peltola H. Model computations on the climate change effects on snow cover, soil moisture and soil frost in the boreal conditions over Finland. Silva Fenn. 2010;44:213–33.

Schweier J, Ludowicy C. Comparison of a cable-based and a ground-based system in flat and soil-sensitive area: A case study from Southern Baden in Germany. Forests. 2020;11:611.

Acknowledgements

We thank Poznań University of Life Sciences for proofreading the manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers whose valuable comments and suggestions greatly enhanced the quality of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Lib4RI – Library for the Research Institutes within the ETH Domain: Eawag, Empa, PSI and WSL. This manuscript was written within the framework of the WSL project “Impact of climate change induced extreme windstorm events on forest management and economy of European forest enterprises”. The publication was co-financed within the framework of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education’s programme: “Regional Initiative Excellence” in the years 2019–2022, Project No. 005/RID/2018/19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Forest Engineering

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanginés de Cárcer, P., Mederski, P.S., Magagnotti, N. et al. The Management Response to Wind Disturbances in European Forests. Curr Forestry Rep 7, 167–180 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-021-00144-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-021-00144-9