Abstract

The identification of psychological strengths that foster healthy development in youth has become a major topic of exploration in the field of positive psychology. Gratitude is a trait-like characteristic with qualities indicative of a potential psychological strength that may serve as a protective factor for early adolescents in the face of stressful life events (SLEs). This two-wave longitudinal study utilized data from a sample of 830 middle school students from the Southeastern United States. Path analysis was employed to investigate gratitude’s role as a moderator in the relations between prior SLEs and early adolescents’ frequencies of externalizing and internalizing coping behaviors. The interaction between SLEs and gratitude significantly predicted early adolescents’ subsequent frequencies of externalizing behaviors, but not internalizing behaviors. The results provided support for gratitude as a key psychological strength in early adolescents. The results also implied the benefits of promoting youths’ gratitude in efforts to prevent externalizing behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Positive psychology focuses on the study of optimal psychological functioning, including personal strengths (e.g., hope, gratitude, prosocial behavior) and environmental assets (e.g., social support; positive school climate) that may serve as protective factors for individuals facing difficult life events (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). One of the primary propositions of positive psychology is that the most effective way to prevent psychological problems is by fostering human strengths and adaptive behaviors (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

Although most early research in positive psychology focused on adults, the role of positive psychology in the lives of children and adolescents has become a topic of widespread interest. Early in the positive psychology movement, Roberts et al. (2002) advocated for the movement’s adoption of a developmental perspective by suggesting that childhood and adolescence represent optimal stages to promote well-being. The third edition of the Handbook of Positive Psychology (Allen et al., 2022) illustrates the fruits of the subsequent increased attention to research with children and youth, including summaries of a large body of research on children’s and adolescents’ strengths and environmental assets, particularly those pertinent to their schooling.

One barrier to optimal youth functioning is the occurrence of stressful life events (SLEs). SLEs are specific traumatic or additive experiences of stressors, which can disrupt an individual's adaptive functioning and lead to immediate and long-term adverse consequences (Cook et al., 2005). For the purposes of our study, we focused on major, discrete life events (e.g., death of a family member, birth of a sibling) that are perceived as negative (see Nunez-Regueiro et al., 2022). Exposure to SLEs has been associated with diminished affect regulation, behavioral control, self-concept, and interpersonal relatedness, leading to an increased risk of both internalizing (i.e., anxious or depressive) and externalizing (i.e., aggressive) responses (Cook et al., 2005; Petruccelli et al., 2019). Both cumulative measures of major SLEs and intensely stressful experiences (e.g., parental divorce, poverty) predict increases in internalizing and externalizing behavior (Grant et al., 2004). Research also suggests that early adolescents (i.e., middle school students) are especially vulnerable to the effects of SLEs (Mann et al., 2014). Early adolescents are just beginning the transition from childhood's relative simplicity to adulthood's complexity (Steinberg, 2005). Many early adolescents are exposed to adult experiences for the first time before developing mature emotional regulation or impulse control and, thus, are more likely to experience heightened sensitivity to SLEs compared to older adolescents (Mann et al., 2014). However, not all adolescents who experience SLEs subsequently demonstrate adverse outcomes, and some may even experience positive outcomes, such as post-traumatic growth (Nishikawa et al., 2018; Shoshani & Slone, 2016). Given the fragility and malleability of early adolescence, such a sensitive period offers a window of not only vulnerability, but also opportunity. As such, investigations on the adaptive characteristics of early adolescents that protect against the adverse impact of SLEs on the well-being of this unique population are warranted.

Character Strengths as Buffers against Stressful Life Events

In the field of positive psychology, personal or character strengths are stable, fulfilling, and valued personality characteristics that, when expressed, lead to positive outcomes for individuals and others (Niemiec, 2018). Studies of possible strengths have included such relatively stable personal characteristics, such as courage, hope, life satisfaction, gratitude, and social skills.

Niemiec (2020) outlined specific functions of character strengths. Although character strengths are pivotal in catalyzing, fostering, and appreciating the positives in life, character strengths also help individuals re-interpret, manage, and buffer the negatives (Niemiec, 2020). In other words, character strengths should moderate the effects of SLEs (Niemiec, 2013, 2020; Suldo & Huebner, 2004). Considering the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), character strengths may permit individuals to appraise and cope adaptively with stressful situations. In this manner, higher levels of a strength, would alter the relation between a risk factor (e.g., SLEs) and an adverse outcome (e.g., externalizing behavior), such that the presence of relatively high levels of the strength (versus low levels) would reduce the relation between the risk factor and the outcome. Thus, the identification of strengths and associated intervention techniques should be a staple in preventing youth maladaptive behaviors.

Gratitude as a Character Strength and Buffer against Stressful Life Events

Gratitude has been proposed as one such character strength (Niemiec, 2018; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Peterson & Seligman (2004) described gratitude as the joy and happiness in response to receiving a gift; the gift may be a tangible one from a benefactor or merely a circumstance. Gratitude has been studied as both a state and a trait. Given our interest in gratitude as a buffer against SLEs, we focused on gratitude as an affective trait-like characteristic; that is, an individual’s somewhat stable, overall disposition to feel grateful.

The importance of gratitude has been considered within main effects models and stress-buffering models. With respect to main effects models, trait gratitude is directly related to many positive outcomes in both adults and youth. For example, recent meta-analytic studies have led to the conclusion that gratitude is negatively associated with depression (Iodice et al., 2021) and positively associated with various indicators of positive well-being (Portocarrero et al., 2020). Furthermore, trait gratitude is associated with positive attributions and motivation, and these processes likely in turn, protect adolescents from developing behavior problems and promote success in school (King & Datu, 2018).

Considering youth specifically, Sun and colleagues (2019) demonstrated that middle school students’ gratitude significantly negatively related to internalizing behavior (e.g., depression, anxiety) as well as externalizing behaviors, (e.g., physical aggression, verbal aggression). Furthermore, of the 24 strengths identified by Peterson & Seligman (2004), gratitude was the only one that predicted an increase in positive emotions over four months in a sample of adolescents (Datu & Mateo, 2020). In addition to better intrapersonal outcomes, gratitude appears to lead to positive interpersonal outcomes. For example, Bono and colleagues (2017) found that early adolescents’ growth in gratitude over a 4-year period positively predicted prosocial behaviors and negatively predicted antisocial behaviors. As a parallel, gratitude also predicts increased social integration in high school students (Bono & Sender, 2018). Finally, Froh and colleagues (2009) observed that early adolescents displaying higher levels of gratitude perceived more peer and familial support and reported more satisfaction with their family, friends, and teachers.

Substantial research supports the main effects model of trait gratitude on the mental health of adults and adolescents. However, much less research has addressed the stress-buffering models of gratitude, which posit that gratitude acts as a moderator of the relation between SLEs and mental health indicators, such as externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Furthermore, such research has focused on adults and adolescents, neglecting early adolescents who are especially vulnerable to the effects of stress.

In a sample of trauma-exposed young adults, while Senger & Gallagher (2023) found that both hope and gratitude predicted resilience, higher levels of gratitude were a more robust predictor of reduced psychological distress and increased well-being than were levels of hope, another character strength. The buffering effect of gratitude has also been supported in college students. For example, Gungor and colleagues (2021) studied the moderating effects of gratitude on the association between SLEs and psychological distress in college students, finding that gratitude moderated the association in that participants with higher levels of gratitude reported weaker levels of psychological distress than those with lower levels of gratitude for both high and low numbers of SLEs. Further, gratitude buffered against developing internalizing behavior (i.e., anxiety and depression) in a sample of college students with ill parents (Stoeckel et al., 2015). Deichert and colleagues (2019) also found that college students who endorsed a greater sense of appreciation of others reported lower levels of depression and physical symptoms when experiencing stress. Such findings have been replicated in older adolescents. Specifically, in a sample of adolescents with a mean age of 16.35 years, higher levels of gratitude buffered the association between SLEs and risk behaviors, such as self-injury and deviant peer affiliation (Wei et al., 2022).

Although the extant studies provide some suggestions of stress-buffering effects of gratitude in adolescents, they are limited in several ways. First, most studies have investigated the effects of exposure to a single SLE (e.g., earthquake, abuse) precluding the effects of multiple, accumulated SLEs. Second, most studies have employed cross-sectional designs; few have employed the longitudinal designs that are preferred in the study of stress-buffering effects. Third, compared to studies of the stress-buffering effects of gratitude in adults and older adolescents, studies of early adolescents (i.e., those under 15 years of age) are very scarce; although, as noted above, middle school students are more vulnerable to experiencing anxiety, depression, and anger associated with SLEs (Mann et al., 2014). Thus, there is a need for investigations of robust, but malleable personal strengths that can buffer early adolescents from the negative influences of accumulated SLEs. Given the positive correlations between gratitude and a host of adaptive outcomes, gratitude seems like a plausible buffer. Such knowledge should provide useful implications for the development of empirically supported mental health promotion programs during early adolescence.

Theoretical Orientations

Algoe’s (2012) find-bind-and-remind theory of gratitude provides a rationale for the investigation of gratitude as a psychological strength; that is, why and how gratitude would act as a buffer for early adolescents faced with SLEs. Given the expanding interpersonal network of early adolescents, the social utility of gratitude is likely implicated in the role of gratitude. As early adolescents begin to socialize more frequently and widely, especially among peers; they should be more likely to seek out social resources to cope with the problems of life (Mitic et al., 2021). According to Gariépy (2016), supportive relationships and social resources protect against the impact of stressors. Through the socially contextualized lens of Algoe's (2012) find-bind-and-remind theory, gratitude functions to initiate, maintain, and strengthen social bonds. More specifically, being grateful for another person's kindness increases one's likelihood of being socially responsive to that person, such as through verbally communicating thanks. Further, this social responsiveness aids one in finding new relationships, reminds them of the value of existing relationships, and binds them to these relationships. Because Algoe (2012) theorizes that gratitude strengthens social bonds and increases the likelihood of receiving social support from others, it would be expected to buffer against stressful experiences by facilitating the social bonds needed by early adolescents to cope with adversity.

The Current Study

The purpose of our study was to evaluate whether gratitude operates as a character strength as proposed by Niemec (2020) and others (e.g., Valle et al., 2006); specifically, whether it buffer the adverse effects of SLEs on early adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behavior. According to Niemiec (2020), character strengths not only are associated with positive outcomes but also serve as protective factors for an individual’s psychological health. Thus, if gratitude is to be considered a viable character strength to foster in early adolescents, relatively high levels of gratitude in this population (versus low levels) should reduce the relation between a risk factor (e.g., SLEs) and an adverse outcome (e.g., externalizing, internalizing behavior). Although some evidence has been provided to support the notion that gratitude buffers against major SLEs in adults and older adolescents, the potential moderating role of gratitude in the relations between SLEs and adverse outcomes has yet to be explored in early adolescents. For this study, we selected externalizing and internalizing behavior as criterion variables because they represented the two most prevalent behavior problems in youth. Moreover, we evaluated both behaviors because some studies have shown differential effects of strengths. For example, Valle et al. (2006) found that hope moderated the effects of SLEs on adolescents’ subsequent internalizing but not externalizing behavior. The identification of buffers against externalizing and/or internalizing behavior at the stage of early adolescence is crucial because as adolescents develop, not only do SLEs predict later internalizing and externalizing behavior, but higher frequencies of maladaptive behaviors, in turn, predict more SLEs the following year (Suldo & Huebner, 2004). Thus, finding that higher levels of gratitude reduce the effects of SLEs in early adolescents would elucidate an additional way to disrupt this harmful cycle and support the early implementation of gratitude-related interventions. Based on Algoe’s (2012) theory, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis One

Early adolescents’ levels of gratitude will moderate the relation between prior SLEs and frequencies of internalizing behavior such that adolescents reporting higher levels of gratitude will display weaker associations between SLEs and internalizing behavior than those reporting lower levels of gratitude.

Hypothesis Two

Early adolescents’ levels of gratitude will moderate the relation between prior SLEs and frequencies of externalizing behavior such that adolescents reporting higher levels of gratitude will display weaker associations between SLES and externalizing behavior than those reporting lower levels of gratitude.

Method

Participants

The participants for this two-wave longitudinal study consisted of students from four public middle schools in the one school district in a southeastern U.S. state. Data were collected over two time points, once in spring 2015 and one year later in spring 2016. A total of 1,216 students from the 6th and 7th grades participated in data collection at Time 1, with 830 of those students also participating at Time 2 as 7th and 8th graders (retention rate = 68%). The attrition rate may be partially attributed to the relatively high student mobility in the school district throughout the course of a school year. Students for whom there were missing data at either time point were subjected to an attrition analysis that involved comparing students who were retained in the study to those who were not. Demographic information (sex, age, grade level, and SES) and variables of interest in the study (internalizing/externalizing behaviors and gratitude) were used to predict the likelihood of being retained in the study via a logistic regression. The results of this regression suggested that grade level was a significant predictor of retention (B = 0.077, SE = 0.038, t = 2.012, p = 0.045), while none of the other variables predicted retention. Specifically, students who were in the 6th grade at Time 1 were more likely to be retained in the study. As such, grade level was included as a covariate in all of the primary analyses.

Of the 830 students who participated at both time points, 42.4% were in the 6th grade and 54.7% were in the 7th grade at Time 1; their ages ranged from 11 to 15 (M = 12.19, SD = 0.75) at Time 1. The sample was composed of approximately the same number of males (48.6%) and females (51.4%). Of the students, 55.8% were Caucasian, 21.9% were African American, 7.9% were biracial, 7.8% were Hispanic/Latino, and 6.7% were of other races, including Native American and Asian American. A student's socioeconomic status (SES) was indicated by qualification for a free or reduced-rate lunch. Students who qualified for free or reduced-rate lunch (36.8%) were classified as low SES, while students who did not qualify for free or reduced-rate lunch (63.2%) were classified as average or above-average SES. Students placed in special education programs were excluded from the study to generalize the results to typical, non-clinical student populations.

Procedure

The data were drawn from an archival dataset, which has been employed in previous research (e.g., Reckart et al., 2017); however, these analyses were novel. Data were collected by school professionals as part of an in-house, districtwide paper and pencil survey of school climate and student well-being. Before collecting data, a letter was distributed to parents that described the survey and instructed the parents to return the letter only if they did not wish their child to participate. Then, during 30-min homeroom periods, teachers administered the various self-report measures together in a packet in one session to the students whose parents gave consent; the same measures were administered on both occasions. Prior to administering the measures, teachers read aloud a script that informed the students of the instructions and purpose of the survey. In addition to the self-report measures of interest, demographic information, including race, sex, age, school grade level, and SES, was collected from the students. To ensure the anonymity of the students and to enable tracking them across the two waves of data collection, students provided their ID numbers rather than their names on the surveys.

Measures

Self-Report Coping Scale

The Self-Report Coping Scale (SRCS) is a 34-item self-report measure that assesses five different types of behaviors in children (Causey & Dubow, 1992). For our purposes, only the Internalizing subscale and Externalizing subscales were used as measures of maladaptive behaviors. The Internalizing subscale of the SRCS consists of seven items; example items are Go off by myself and Worry that others will think badly of me. The Externalizing subscale consists of four items; example items are Yell to let off steam and Get mad and throw or hit something. Children reported how often they engage in each behavior in response to a hypothetical, stressful interpersonal situation at school (i.e.,”…have an argument or fight with a friend”) by rating each of the items on a 5-point response format that ranged from never (1) to always (5). Higher scores on these subscales indicated higher frequencies of behaviors. Given time and space limitations, the version of the SCRS used in the current study did not include items from the original version that addressed an academic situation at school.

The construct validity of the SCRS is supported by various criterion indices, which include peer ratings of the children's behavior and self-reports of self-competence and anxiety (Causey & Dubow, 1992). The internal consistencies of the subscales of the ranged from 0.66 to 0.76 (Causey & Dubow, 1992; Roecker Phelps, 2001). Two-week test–retest coefficient ranged from 0.59 to 0.78 for the subscales (Causey & Dubow, 1992; Roecker Phelps, 2001). The coefficient alphas for the Internalizing and Externalizing subscales of this abbreviated version of the SCRS with this sample at both time points were 0.78/0.79 and 0.79/0.75, respectively.

Life Events Checklist

The Life Events Checklist (LEC) is a 46-item self-report checklist in which children of ages 8 to 18 indicate the occurrence of SLEs during the previous year (Johnson & McCutcheon, 1980). Only the first 18 items of the LEC were administered, which were those that referred to uncontrollable SLEs. Examples of these items included parental divorce, death of a close friend, changing schools, and birth of a sibling (see the Supplementary Information for the complete list of items). These items can be differentiated from controllable events because uncontrollable events may be more likely to elicit problem behaviors and because controllable events might reflect symptoms of distress as opposed to independent sources of distress (Grant et al., 2004). Consistent with Brand and Johnson’s (1982) method of scoring the LEC and with the conclusion of Nunez-Regueiro et al. (2022) that measures of both occurrence and valence are essential to support the validity of SLE measures, participants indicated the presence or absence of the events during the past year and whether the events were experienced as negative or positive. Each student's score thus could range from 0 to l8, with higher scores indicating a greater occurrence of uncontrollable SLEs that were rated as negative.

The 46-item LEC has received support for its reliability and validity. Regarding test–retest reliability, Brand & Johnson (1982) reported that the LEC's two-week test–retest coefficient was 0.72 for negative SLEs. Furthermore, significant correlations have been reported between the LEC and other measures of SLEs, such as the Stressful Life Events Schedule for Children and Adolescents and the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule, indicating good convergent validity (Duggal et al., 2000). Significant correlations between the LEC and measures of related youth outcomes, such as depression, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder, have also supported its validity (Johnson & McCutcheon, 1980; Meade et al., 2001; Tiet et al., 2001).

Suldo & Huebner (2004) provided evidence for the psychometric properties of a modified version of the LEC used in their study with middle and high school students. Their version of the LEC was based on the same 18 items as the version of the LEC employed in the current study; however, the scoring procedures differed. Suldo and Huebner instructed students to indicate the occurrence versus non-occurrence of the events but, unlike the current study, they did not also instruct the students to indicate whether the event was experienced as negative or positive. Using their scoring system, they reported a 1-year test–retest coefficient of 0.40. Furthermore, because the LEC consisted of separately occurring events that would not be expected to intercorrelate, they did not calculate its internal consistency reliability. Finally, Suldo and Huebner reported statistically significant correlations between Time 1 SLE scores and internalizing and externalizing behaviors at Time 1 and Time 2, supporting the concurrent and predictive validity of the measure.

Regarding the current study, the 1-year test–retest reliability coefficient for our modified version of the LEC was 0.56., and Time 1 SLE scores correlated significantly with internalizing and externalizing behavior at Time 1 and Time 2. These findings provide some support for the reliability and validity of our modified version of the LEC.

Gratitude Questionnaire-6

The Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6) is a 6-item self-report questionnaire that measures a person's trait gratitude (McCullough et al., 2002). Example items are I have so much in life to be thankful for and I am grateful to a wide variety of people. According to Froh et al. (2011), the GQ-6 is a more effective measure of gratitude in youth and adolescents when only the first five items are administered due to the inappropriateness of the sixth question (i.e., Long amounts of time can go by before I feel grateful to something or someone) when considering the developmental level of youth. In their sample, the sixth item displayed a low factor loading, and youth reported the item was “difficult to understand” and “very abstract.” Thus, only the first five items were administered. Students responded to each item using a 7-point response format that ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) with higher scores indicating greater gratitude.

The GQ-6 has received support for its validity. Its internal consistency reliability has been reported as 0.70 or higher for various age groups (Froh et al., 2011). Furthermore, significant convergent validity correlations have been reported between the GQ-6 and the Gratitude Adjective Checklist (GAC; McCullough et al., 2002) as well as the Gratitude Resentment Appreciation Test-short form (GRAT-short; Watkins et al., 2003). The coefficient alpha for the abbreviated GQ-6 with this sample was 0.81.

Data Analysis Plan

Descriptive analyses and correlations among the predictor and criterion variables are displayed in Table 1. The correlations suggested no issues of multicollinearity (i.e., no correlations above 0.7). Mardia’s (1970) test indicated significant multivariate skewness (β = 18, p < 0.01) and kurtosis (β = 89, p < 0.01) in the data. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was thus used in the primary analyses to combat departures in multivariate normality. Robust indications of fit were also used to evaluate goodness-of-fit for the model. Little’s (1988) Test was performed to determine if data were missing completely at random (MCAR) in the sample. Given that the data were determined to be MCAR (χ2 = 91.29, df = 77, p = 0.127), we utilized full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to address missing data in the primary analyses. FIML is a model-based approach for addressing missing data that involves directly estimating parameter estimates and standard errors from the data, rather than imputing missing values (Enders, 2010). FIML procedures tend to outperform other methods for handling missing data in terms of power (Nicholson et al., 2017).

The primary analyses were performed via path analysis using the Lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) for R (v4.2.2; Core Team 2022). First, it was determined whether the data fit the model as indicated by the Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Standardized Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The chi-square goodness-of-fit test was also considered but given less weight in decisions regarding fit due to its sensitivity to large sample sizes (Kline, 2010). CFI and TLI values greater than 0.90–0.95 (Kline, 1998), RMSEA values less than 0.06, and SRMR less than 0.08 were considered indicators of acceptable fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Once model fit was established, the significant paths were identified via significance testing of the regression coefficients. Significant moderation effects were subjected to graphing and significance probing to understand the nature of the moderating effects. Moderation effects were probed using the “pick-a-point” or “simple slopes” approach (Rogosa, 1980) and a Johnson-Neyman interval (Johnson & Fay, 1950). Graphical representations of these analyses were also included. Nonsignificant moderating effects were not evaluated further. Moderation probing analyses were performed via the “interactions” package (Long, 2019) for R (v4.2.2; Core Team 2022). Control variables were included in the primary path model and in the mediation probing analyses. The control variables (i.e., child sex, SES, racial identity, and grade level) were selected based on their known association to the criterion variables (i.e., externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior) (e.g., Causey & Dubow, 1992) and/or to the predictor variables (e.g., Reckart et al., 2017) in the model.

Results

Correlational Analyses

These negative SLEs displayed a significant inverse correlation with gratitude at Time 1 and significant positive correlations with internalizing and externalizing behavior at Time 1 and Time 2. Furthermore, the correlations between gratitude and internalizing and externalizing behavior at both times were also significantly negative. Externalizing and internalizing behaviors were also significantly positively correlated with each other at both times.

Path Modeling of Main and Moderating Effects

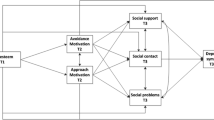

Standardized and unstandardized results of the path analysis testing the statistical significance of the associations between SLEs and internalizing and externalizing behavior, as well as the moderating effect of gratitude, are displayed in Table 2 as well as in Fig. 1. Model fit was acceptable, χ2(22) = 52.71 (p < 0.001), CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.042, 90% CI [0.028, 0.055], SRMR = 0.038. The model explained 36.3% of the variance in externalizing behavior as well as 35.7% of the variance in internalizing behavior. A significant association was found between SLEs and internalizing behavior (β = 0.072, p = 0.026), but not between SLEs and externalizing behavior (β = 0.049, p = 0.140). Gratitude was also significantly associated with both internalizing (β = -0.090, p = 0.003) and externalizing behaviors (β = -0.094, p = 0.005). Of the two moderating effects examined, only the interaction between gratitude and SLEs in predicting externalizing behaviors was statistically significant (β = -0.079, p = 0.005).

For these students, more frequent experiences of stressful life events were prospectively associated with more frequent internalizing behavior, while higher levels of gratitude were prospectively associated with fewer internalizing behaviors. Given the significance of the interaction between gratitude and SLEs in predicting externalizing behavior, the main effects were not interpreted. Rather, this interaction effect was subjected to probing analyses to better understand the underlying relation between these variables.

Probing and Graphing of Significant Moderation Effects

To fully understand the moderating effect of gratitude on the relation between SLEs and externalizing behavior, “pick-a-point” or “simple slopes” analysis (Rogosa, 1980) and a Johnson-Neyman interval (Johnson & Fay, 1950) were employed. These analyses were also graphically represented to increase interpretability. To further aid in interpretability, variables were left unstandardized for these plots, although standardized estimates and squared semi-partial correlations (sr2) were also generated to yield information about effect size.

For the simple slopes analysis, the significance of the association between SLEs and externalizing behavior was examined at three levels (16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles) of the moderating variable of gratitude. The association between SLEs and gratitude was only significant when the moderator variable (gratitude) was set to the 16th percentile (β = 0.118, p = 0.008, sr2 = 0.01). So, for students reporting relatively low gratitude (mean score = 4.8), SLEs were significantly related to externalizing behavior, while this was not true of students with higher levels of gratitude (see Fig. 2).

The Johnson-Neyman interval (Johnson & Fay, 1950) complemented the simple slopes analysis by indicating for which values of gratitude, the association between SLEs and externalizing behavior was significant in a more continuous manner. The association between SLEs and externalizing behavior was significant at p < 0.05 outside of the interval [5.463, 8.782]. A negative trend was observed in the strength of the association between SLEs and externalizing behavior as levels of gratitude increased (see Fig. 3). The false discovery rate was controlled using the procedure described in Esarey & Sumner (2018).

Discussion

Identifying and fostering psychological strengths in youth is imperative to prevent maladaptive behavior and develop healthy outcomes. According to some researchers (e.g., Niemiec, 2020; Suldo & Huebner, 2004), for a psychological characteristic to be considered a psychological strength, it must serve as a buffer in the relation between SLEs and maladaptive behavior. Although studies have supported the role of positive, trait-like characteristics, such as life satisfaction and hope, as psychological strengths in youth (Suldo & Huebner, 2004; Valle et al., 2006), gratitude is a positive, trait-like characteristic that has yet to be explored in this manner with early adolescents. Therefore, we aimed to determine if gratitude acts as a psychological strength by investigating its ability to buffer against the adverse effects of SLEs in early adolescents. Specifically, the study examined whether gratitude moderated the relations between prior SLEs and early adolescents’ frequencies of subsequent internalizing behavior and externalizing behavior using a longitudinal design.

Our study confirmed findings from previous studies and yielded novel discoveries. First, zero-order correlations revealed significant negative relations among gratitude and SLEs, internalizing behavior, and externalizing behavior. These results are commensurate with previous studies (e.g., Froh et al., 2011; Hasemeyer, 2013; Reckart et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2019). Not surprisingly, youth who experienced more SLEs were less likely to report higher levels of gratitude. Furthermore, youth who reported higher gratitude also reported fewer internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Consistent with Algoe’s (2012) find-bind-and-remind theory of gratitude and Fredrickson’s (2013) broaden-and build theory of emotions, frequent gratitude appears to lead to more resources, perhaps including increased social ties and a broadened array of adaptive behaviors, likely reducing the emergence of maladaptive behaviors.

Second, our study provided partial support for the hypothesized model of gratitude as a moderator of the relations between SLEs and maladaptive behavior. Specifically, the interaction between prior SLEs and gratitude significantly predicted early adolescents’ externalizing behavior, but not internalizing behavior. Thus, grateful youth may be less likely to experience increases in externalizing behavior when confronted with SLEs. Therefore, our study provided evidence that the experience of gratitude promotes the relative absence of externalizing behavior by buffering against the harmful effects of stress. As noted previously, this mechanism is likely due to gratitude, as a positive emotional characteristic, broadens and builds the personal resource available in varying situations (Algoe, 2012; Fredrickson, 2013).

Third, that gratitude buffered against externalizing, but not internalizing behavior, strengthens the discriminant validity of the constructs of gratitude and hope. In a prior study investigating hope as a psychological strength, Valle et al. (2006) observed that unlike gratitude, adolescents’ hope buffered against increases in internalizing behavior, not externalizing behavior (Valle et al., 2006). Although the reason for the differences in effects across the behaviors is unclear, one explanation may involve fundamental temporal differences. Whereas gratitude involves the appreciation of benefits that have already been received, hope consists of the anticipation of achieving a desired, future outcome (Snyder et al., 2002). Gratitude thus represents a past-oriented construct, whereas hope represents a future-oriented construct. Future-orientation is defined as the degree to which adolescents think about the future, anticipate future consequences, and plan before acting (Steinberg et al., 2009). A future-orientation has been suggested to protect against the development of internalizing behavior; specifically depressive, anxious, and suicidal behavior (Anagnostopoulos & Griva, 2012). Thus, adolescents who are less hopeful may be less likely to envision their future as being different from their present, leading to internalizing behavior. On the other hand, given that the expression of gratitude involves being appreciative of prior experiences, those individuals who are ungrateful are more likely to harbor anger and resentment towards others, engaging in externalizing behavior (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Another possible reason may be related to Algoe’s (2012) theory of gratitude in that externalizing behavior may be more socially contextualized than internalizing behavior, reflecting the social nature of gratitude.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

To the authors’ knowledge, our study was the first to evaluate gratitude as a buffer against the association between accumulated SLEs and externalizing and internalizing behavior in young adolescents. Accordingly, the results provided preliminary evidence that gratitude is a psychological strength that protects against the development of externalizing behavior in the face of prior SLEs. The finding that gratitude buffers externalizing, but not internalizing behavior is intriguing and warrants further exploration. Nevertheless, the study reflected important limitations. First, the sample was not representative of the nation, especially regarding race and geographic location, or other countries. Future research should employ more representative and international samples and include differing age groups to strengthen the generalizability of findings. Second, data were collected exclusively from self-reports. Although there is some evidence for the validity of the measures, student responses may have reflected social desirability responding, resulting in measurement error. Future research should incorporate multiple methods of assessment, such as parent and teacher reports, to enhance the validity of measurements. Third, although statistically significant, the effect size for the relation between SLEs and externalizing behavior at the 16th percentile was small (Cohen, 1988); nonetheless, the effect reflected the significant, unique variance explained over and above the effects of the baseline level of externalizing behavior and the selected demographic variables. Furthermore, small effects may accumulate over time to become large effects (e.g., Ellis, 2010). Fourth, although the prevalence of SLEs in early adolescents using our scoring procedure is unknown, the exposure to SLEs seemed fairly low in this sample; the mean number of SLEs experienced by the participants was 2.0. However, when re-scoring our measures for the total number of occurrences (negative + positive), we obtained means of 3.76 (SD = 2.76) and 3.23 (SD = 2.80) at Time 1 and 2 respectively. Our means were thus somewhat similar to those reported for the adolescent sample of Suldo & Huebner (2004) in which the mean numbers of total occurrences were 4.99 (SD = 3.23) and 3.57 (SD = 2.69) at Time 1 and Time 2 respectively, suggesting some comparability of the samples. The restricted ranges of SLEs, particularly in our study when measured as the number of negative experiences, may have attenuated the magnitude of the associations between the LEC scores and the other variables, yielding spuriously low estimations of the effects of the SLEs. Thus, the generalizability of the results should be interpreted cautiously. With samples displaying more dispersion of SLEs, larger effect sizes might be expected. On the other hand, at higher levels of stress, gratitude may not be sufficient to mitigate the adverse consequences. Thus, future research is needed to examine gratitude as a moderator between SLEs and behavior in a variety of populations, especially more vulnerable populations. Finally, studies of the interactions between gratitude and differing types of life events (e.g., negative versus positive, chronic versus acute, uncontrollable versus controllable) would be beneficial to clarify gratitude’s effectiveness across varying conditions.

Implications for Professionals

The findings suggest implications for professional practice. As early adolescents who reported higher levels of gratitude were less at risk for experiencing increases in externalizing behavior when faced with SLEs, the early implementation of gratitude-related assessments and interventions should be encouraged. One example of a developmentally appropriate school-wide mental health screener that incorporates a brief measure of gratitude is the Social and Emotional Health Survey (Furlong et al., 2014; also see https://www.covitalityucsb.info/research/html). Regarding interventions, because it is impossible to shelter youth from all adverse experiences in life, professionals should consider recommending interventions to develop gratitude, especially for youth who exhibit early signs of externalizing behavior. According to Lomas et al. (2014), activities that foster gratitude can be easily integrated into reading and writing programs in the school setting, especially due to the recent infusion of social-emotional learning. For more information, interested school professionals could consult Suldo et al. (2021) for a summary of relevant empirically supported school-based programs to promote gratitude and Allen et al. (2022) for research on a variety of potential student strengths and environmental assets that may serve as buffers against challenging life experiences.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, E.S.H.

References

Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x

Allen, K.A., Furlong, M.J., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Suldo, S.M. (2022). Handbook of positive psychology in schools: Supporting processes and practice. Routledge.

Anagnostopoulos, & Griva, F., (2012). Exploring time perspective in Greek young adults: Validation of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory and relationships with mental health indicators. Social Indicators Research, 106(1), 41–59https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9792-y

Bono, G., Froh, J. J., Disabato, D., Blalock, D., McKnight, P., & Bausert, S. (2019). Gratitude’s role in adolescent antisocial and prosocial behavior: A 4-year longitudinal investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(2), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1402078

Bono, G., & Sender, J. T. (2018). How gratitude connects humans to the best in themselves and in others. Research in Human Development, 15(3–4), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2018.1499350

Brand, A. H., & Johnson, J. H. (1982). Note on reliability of the life events checklist. Psychological Reports, 50(3_suppl), 1274–1274. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1982.50.3c.1274

Causey, D. L., & Dubow, E. F. (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2101_8

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., DeRosa, R., Hubbard, R., Kagan, R., Liautaud, J., Mallah, K., Olafson, E., & van der Kolk, B. (2005). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20050501-05

Datu, J. A. D., & Mateo, N. J. (2020). Character strengths, academic self-efficacy, and well-being outcomes in the Philippines: A longitudinal study. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, Article 105649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105649

Deichert, N. T., Chicken, M. P., & Hodgman, L. (2019). Appreciation of others buffers the associations of stressful life events with depressive and physical symptoms. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 20(4), 1071–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9988-9

Duggal, S., Malkoff-Schwartz, S., Birmaher, B., Anderson, B. P., Matty, M. K., Houck, P. R., Bailey-Orr, M., Williamson, D. E., & Frank, E. (2000). Assessment of life stress in adolescents: Self-report versus interview methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(4), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200004000-00013

Ellis, P. D. (2010). The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes. Cambridge University Presshttps://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511761676

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guildford.

Esarey, J., & Sumner, J. L. (2018). Marginal effects in interaction models: Determining and controlling the false positive rate. Comparative Political Studies, 51(9), 1144–1176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017730080

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In P. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 1–53). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Froh, J. J., Fan, J., Emmons, R. A., Bono, G., Huebner, E. S., & Watkins, P. (2011). Measuring gratitude in youth: Assessing the psychometric properties of adult gratitude scales in children and adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021590

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006

Furlong, You, S., Renshaw, T. L., Smith, D. C., & O’Malley, M. D. (2014). Preliminary Development and Validation of the Social and Emotional Health Survey for secondary school students. Social Indicators Research, 117(3), 1011–1032https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0373-0

Gariépy, G., Honkaniemi, H., & Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: A systematic review of current findings in Western countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 209(4), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094

Grant, K. E., Compas, B. E., Thurm, A. E., McMahon, S. D., & Gipson, P. Y. (2004). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Measurement issues and prospective effects. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(2), 412–425. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23

Gungor, A., Young, M. E., & Sivo, S. A. (2021). Negative life events and psychological distress and life satisfaction in US college students: The moderating effects of optimism, hope, and gratitude. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPR.2021472963

Hasemeyer, M. D. (2013). The relationship between gratitude and psychological, social, and academic functioning in middle adolescence. [Unpublished Doctoral Thesis]. University of South Florida.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Iodice, J. A., Malouff, J. M., & Schutte, N. S. (2021). The association between gratitude and depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.23937/2643-4059/1710024

Johnson, J. H., & McCutcheon, S. (1980). Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the Life Events Checklist. In I. G. Sarason & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Stress and Anxiety (Vol. 7, pp. 111–125). Hemisphere Press.

Johnson, P. O., & Fay, L. C. (1950). The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika, 15(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02288864

King, R. B., & Datu, J. A. D. (2018). Grateful students are motivated, engaged, and successful in school: Cross-sectional, longitudinal, and experimental evidence. Journal of School Psychology, 70, 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.08.001

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guildford.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guildford.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Lomas, T., Froh, J. J., Emmons, R. A., Mishra, A. and Bono, G. (2014). Gratitude interventions: A review and future agenda. In A. C. Parks & S. M. Schueller (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Positive Psychological Interventions (pp. 3- 19). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118315927

Long, J.A. (2019). Interactions: Comprehensive, user-friendly toolkit for probing interactions. R package version 1.1.0, https://cran.r-project.org/package=interactions.

Mann, M. J., Kristjansson, A. L., Sigfusdottir, I. D., & Smith, M. L. (2014). The impact of negative life events on young adolescents: Comparing the relative vulnerability of middle level, high school, and college-age students RMLE Online. Research in Middle Level Education, 38(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2014.11462115

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57(3), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/57.3.519

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

Meade, J. A., Lumley, M. A., & Casey, R. J. (2001). Stress, emotional skill, and illness in children: The importance of distinguishing between children’s and parents’ reports of illness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(3), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00733

Mitic, M., Woodcock, K. A., Amering, M., Krammer, I., Stiehl, K. A. M., Zehetmayer, S., & Schrank, B. (2021). Toward an integrated model of supportive peer relationships in early adolescence: A systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 589403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.589403

Nicholson, J. S., Deboeck, P. R., & Howard, W. (2017). Attrition in developmental psychology: A review of modern missing data reporting and practices. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415618275

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (the first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives from positive psychology (pp. 11–29). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4611-4_2

Niemiec, R. M. (2018). Character strengths interventions: A field guide for practitioners. Hogrefe Publishing.

Niemiec, R. M. (2020). Six functions of character strengths for thriving at times of adversity and opportunity: A theoretical perspective. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9692-2

Nishikawa, S., Fujisawa, T. X., Kojima, M., & Tomoda, A. (2018). Type and timing of negative life events are associated with adolescent depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 41–41. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00041

Nunez-Regueiro, F., Archambault, I., Bressoux, P., & Nurra, C. L. (2022). Measuring stressors among children and adolescents: A scoping review 1956–2020. Adolescent Research Review, 7(14), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00168-z

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Gratitude. In Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Petruccelli, K., Davis, J., & Berman, T. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104127–104127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127

Portocarrero, F. F., Gonzalez, K., & Ekema-Agbaw, M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 164, 110101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110101

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/

Reckart, H., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2017). A preliminary study of the origins of early adolescents’ gratitude differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.020

Roberts, M. C., Brown, K. J., Johnson, R. J., & Reinke, J. (2002). Positive psychology for children: Development, prevention, and promotion. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 663–675). Oxford University Press.

Roecker Phelps, C. E. (2001). Children’s responses to overt and relational aggression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 30(2), 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_11

Rogosa, D. (1980). Comparing nonparallel regression lines. Psychological Bulletin, 88(2), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.307

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Senger, A. R., & Gallagher, M. W. (2023). The unique effects of hope and gratitude on psychological distress and well-being in trauma-exposed Hispanic/Latino adults. Psychological Traumahttps://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001550

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2016). The resilience function of character strengths in the face of war and protracted conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 2006–2006. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02006

Snyder, Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Mann Pulvers, K., Adams, V. H., & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 820–826https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.820

Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005

Steinberg, Graham, S., O’Brien, L., Woolard, J., Cauffman, E., & Banich, M. (2009). Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development, 80(1), 28–44https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01244

Stoeckel, M., Weissbrod, C., & Ahrens, A. (2015). The adolescent response to parental illness: The influence of dispositional gratitude. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(5), 1501–1509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9955-y

Suldo, S., & Huebner, E. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? School Psychology Quarterly, 19, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.19.2.93.33313

Suldo, S. M., Mariano, J. M., & Gilfix, H. (2021). Promoting students’ positive emotions, character, and purpose. In P. J. Lazarus, S. M. Suldo, & B. Doll (Eds.), Fostering the emotional well-being of our youth: A school-based approach (pp. 282–312). Oxford University Press.

Sun, P., Sun, Y., Jiang, H., Jia, R., & Li, Z. (2019). Gratitude and problem behaviors in adolescents: The mediating roles of positive and negative coping styles. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1547. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01547

Tiet, Q., Bird, H., Hoven, C., Moore, R., Wu, P., Wicks, J., Jensen, P., Goodman, S., & Cohen, P. (2001). Relationship between specific adverse life events and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(2), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005288130494

Valle, M. F., Huebner, E. S., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). An analysis of hope as a psychological strength. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.03.005

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 31(5), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2003.31.5.431

Wei, C., Wang, Y., Ma, T., Zou, Q., Xu, Q., Lu, H., Li, Z., & Yu, C. (2022). Gratitude buffers the effects of stressful life events and deviant peer affiliation on adolescents’ non-suicidal self-injury. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 939974–939974. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.939974

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271–1288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1271

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Mimi S. Webb, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Webb, M.S., Whitmire, J.B., Hills, K.J. et al. Gratitude Buffers Against the Effects of Stressful Life Events on Adolescents’ Externalizing Behavior but Not Internalizing Behavior. Contemp School Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-024-00497-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-024-00497-5