Abstract

Students who have remained classified as English Learners (ELs) for more than six years are often labeled “Long-term English Learners” (LTELs). The present study examined the English Language Development (ELD) test scores and demographic information in a group of 560 students identified as LTELs. Despite assumptions that these students are still learning English, results showed many students who are labeled LTELs exhibited advanced English skills, especially on measures of expressive and receptive oral language (i.e., speaking and listening subtests). At the same time, ELD assessments showed many of these students struggled with literacy skills, especially reading. Perhaps due to these overlapping circumstances, we found many LTELs were also identified with learning disabilities. Based on these findings, we explored the impact of restricting domains needed for reclassification as English proficient on reclassification rates. Compared with existing decision rules in the students’ state, proposed models allow many more LTELs to reclassify as English proficient, and most LTELs not reclassifying are students in special education. Discussion focuses on interpreting ELD scores for students who have remained classified as ELs for more than a few years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many children enter schools in the United States speaking a language other than English. In 21% of American households, a language other than English is spoken (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). Some children from these households have fluent bilingual skills in English and the home language reported, but those students not already proficient in English at school entry are designated as English Learners (ELs) following formal language testing. About 4.8 million, approximately 10% of all American public school students, are identified ELs (McFarland et al., 2018). Some states have much higher rates of ELs. In California, for instance, the percentage of students who are ELs is around 18%, over one million students (California Department of Education [CDE], 2021). ELs usually need between four and eight years of instruction to become academically proficient in English (Collier, 1987; Hakuta et al., 2000). Compared to students who have never been ELs, ELs who are reclassified as English proficient often have the same, or even better, academic outcomes (Hill et al., 2014). These higher academic outcomes are at least partially due to the fact that ELs must perform at a high level of academic achievement as part of the reclassification criteria. These advantages may also be due to the substantial benefits associated with bilingualism (e.g., Adesope et al., 2010).

The EL status is meant to be a temporary designation, used until the student becomes English proficient, which generally happens in elementary school (Slama, 2014). However, some students enter kindergarten as ELs and remain ELs into middle and high school. Students who remain classified as ELs for more than six years are often referred to as Long-term English Learners (LTELs; Menken & Kleyn, 2010; Olsen, 2010). In some large, urban areas, more than half of ELs in secondary schools are designated LTELs (Callahan, 2005; Menken et al., 2012; Olsen, 2010; Yang et al., 2001), which suggests many thousands of American students have this label. (Exact numbers of students who are designated LTELs are not collected by state education agencies.)

Studies on LTELs' academic achievement show a general pattern of low achievement—low grades, low scores on standardized tests, and low graduation and college attendance rates (Callahan, 2005; Kanno & Cromley, 2013; Menken & Kleyn, 2010; Olsen, 2010). More nuanced examinations into students who are LTELs’ academic achievement, however, show these students’ academic stories are much more complex. Qualitative studies show some students designated as LTELs comprehend and analyze high school level texts in meaningful ways (Brooks, 2015, 2016). Additionally, Hernandez’s (2017) case studies of LTELs included a description of a student who did not understand why she had an LTEL label. Her confusion stemmed from the fact that her English was similar to her White, monolingual peers’ English, her Spanish was much better than their Spanish, and she was born in the U.S. (Hernandez, 2017). These studies also highlight a common but often ignored strength, these students’ translanguaging skills. Studies have described how LTELs skillfully and frequently use translanguaging skills as they switch back and forth between two or more languages while at school (Kibler et al., 2018; Menken & Kleyn, 2010). To summarize, students designated as LTELs are a complex, yet understudied, group of students.

Relationships between EL/LTEL Status and Demographic Characteristics

The vast majority of LTELs are Spanish-speaking Latinx students. Nationally, across all grades, 80% of ELs are Latinx and 77% speak Spanish (McFarland et al., 2018), and these students disproportionally attend schools where many, if not most, students are ELs and racial and ethnic minorities from low-income families (Cosentino de Cohen et al., 2005). Taken together, many Latinx students face a “triple segregation” where they are segregated in schools by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and language (Gandara, 2010). Because of this segregation, many Spanish-speaking Latinx students have limited exposure to standard, academic, American English, which may be an important factor in opportunity to learn and eventual reclassification as proficient in English.

Another factor related to language proficiency is gender. Girls identified as ELs, for example, have been shown to perform better than EL boys on measures of oral language and literacy in both English and their home language (Linklater et al., 2009; Rojas & Iglesias, 2013). Given this relationship, it is not surprising that EL identification rates differ by gender, and there are more boys than girls identified as ELs. Taken together, Latinx students, students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and boys are likely to be overrepresented in groups of students identified as ELs or LTELs.

LTELs in Special Education

Across all grades, nationally, 14% of students who are ELs are eligible for special education services due to a disability, and the most common identified disability for all students, and students who are ELs, is a learning disability (LD; U.S. Department of Education, 2017). There is minimal research on LTELs in special education. One exception is Thompson’s (2015) mixed method study which reported around 35% of LTELs in one district were also in special education, with most identified with an LD. Thompson’s study also reported that in seven other California school districts between 25 and 33% of LTELs were in special education. These rates are much higher than the national average of public school students in special education, which is around 13% (McFarland et al., 2018). Additionally, Shin (2020) found that students in special education in kindergarten were at increased risk of being classified as LTELs several years later.

Kim and García’s (2014) study of LTELs found, out of the 13 LTELs studied, three were referred to special education in 4th or 5th grade. Despite the fact these students went on to fail both mathematics and reading state assessments in high school, none of the three were found eligible for special education services (Kim & García, 2014). Another well-documented case study of a student identified as an LTEL with an LD showed her teachers were concerned she might have an LD as early as 2nd grade (Thompson, 2015). However, because of her EL status, there were delays in her formal assessments, and she was not identified as a student with an LD until 8th grade. In this student’s case, the LD label, and not the LTEL label, was linked to academic support services in middle and high school.

These studies highlight the challenge of teasing apart the cause of school struggle in ELs in older grade levels. For these students, it is often unclear if their academic challenges are due to their needing more time to acquire English, or an underlying language or learning disability is to blame (Klingner et al., 2006; Shore & Sabatini, 2009). Adding to the confusion, most schools do not have clear policies for identifying ELs with LDs, so teachers are hesitant to refer ELs for special education testing (Zehler et al., 2003). Consequently, compared to their monolingual peers with an LD, ELs with an LD can be delayed getting into special education for several years (Samson & Lesaux, 2009). This is troubling because, compared to similar students who enter special education later, students who enter into special education earlier benefit from additional services and end up with higher academic achievement (e.g., Ehrhardt et al., 2013).

Services and Supports for LTELs

The EL or LTEL label is intended to be tied to helpful services. However, this is not always the case for LTEL students. Few middle and high schools have programs especially designed for LTELs, and up to three-quarters of LTELs spend several years with no English language support services (Kim & García, 2014; Menken & Kleyn, 2010; Thompson, 2015). When LTELs do receive EL services in upper grades, they are likely to be placed in classes created for newcomer English Learners (Menken & Kleyn, 2010; Olsen, 2010; Thompson, 2015; Yang et al., 2001). Although these classes can be helpful for recent immigrants, they are inappropriate for LTELs (Callahan et al., 2010; Menken & Kleyn, 2010). Slightly more advanced “sheltered classes” are also meant to support LTELs’ linguistic challenges, but qualitative studies show that high school sheltered classes for LTELs are often stigmatized, and students believe these classes are for students who are less intelligent (Dabach, 2014). Not surprisingly, high school programs for LTELs are not associated with improved English skills (Callahan et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2001). Additionally, these required classes can prevent LTELs from taking college preparatory courses and other more rigorous classes, which are necessary for college admission (Callahan et al., 2010; Kanno & Kangas, 2014; Kim & García, 2014). Callahan (2005), for example, found less than 2% of the LTELs in her study had taken the necessary classes required for admission to a 4-year college, and only 15% had taken one or more college preparation courses. To avoid the pitfalls associated with the LTEL label, ELs must reclassify as proficient in English.

Reclassification as English Proficient

Screening assessments and criteria to determine proficiency levels and eventual reclassification as English proficient vary from state to state (Linquanti & Cook, 2013), but generally, LTELs must pass a test of basic skills in English and a grade level, standards-based English content assessment to leave their label behind. Other requirements for reclassification as English proficient are less clearly related to English proficiency. Many school districts use Math proficiency, as measured on a state-wide assessment, as a required component of English proficiency, and Math scores have been shown to prevent some LTELs from being reclassified as proficient in English (Hill et al., 2014; Thompson, 2015). Additionally, 16% of school districts in a sample of California school districts report using “discipline” as part of their reclassification criteria (Hill et al., 2014). These requirements, not directly related to English acquisition, highlight the fact that many school districts have stricter reclassification criteria than what is recommended by state departments of education. Although well-intentioned, these stricter reclassification criteria for LTELs are negatively associated with students graduating from high school with a diploma (Hill et al., 2014). There are also concerns that some of these policies might keep students classified as ELs longer than necessary (Carroll & Bailey, 2016).

In addition, it is important to point out that prior studies have shown, in some schools, a significant proportion of monolingual English-speaking students would not meet the criteria ELs must meet to be reclassified (CDE, 2011; Carroll & Bailey, 2016; Yang et al., 2001). Further, even when LTELs meet the criteria for reclassification, bureaucratic issues related to tracking student performance on multiple assessments coupled with frequently changing criteria for reclassification can leave students designated as ELs long after they have met current criteria for reclassification (Carroll & Bailey, 2016; Hill et al., 2014; Thompson, 2015).

Reclassifying is especially difficult for those students dual identified as LTELs in special education. Compared to students who are ELs without disabilities, ELs with disabilities have been shown to have lower scores on literacy assessments (Solari et al., 2014). Thus, the requirement for LTELs to pass the reading and writing sections of the assessment is likely to disproportionately impact LTELs with disabilities.

Research Questions

In sum, quantitative studies on LTELs tend to narrowly focus on the gaps between LTELs and their non-LTEL peers. Qualitative case studies, on the other hand, have provided a rich portrait of students who are LTELs’ academic experiences and perceptions (e.g., Brooks, 2015; Flores et al., 2015; Hernandez, 2017; Thompson, 2015). Some of these qualitative studies include assessment data (e.g., Kibler et al., 2018; Kim and García, 2014), but the sample sizes are generally small. Hill and colleagues (2014) completed a secondary data analysis on a large number of students identified as LTELs’ English language assessment data, but they excluded students in special education. A nontrivial number of LTELs are in special education with language and learning challenges (Thompson, 2015), so these students should be included in an analysis of students who are labeled LTELs. Thompson’s (2015) study on LTELs included the test scores of students in special education but did not include an analysis of special education students’ test scores or an overall analysis of English skills by domain (i.e., reading, speaking). To address these gaps in the literature, the present study analyzes domain-specific (i.e., reading, writing, listening, and speaking) English Language Development skills of more than 500 students identified as LTELs, and we include students who are identified as LTELs in special education. In doing so, we aim to provide a more complete view of students with the LTEL designation.

The current study examines important correlates of LTEL status in order to better understand the needs of this population of students. Specifically, we ask:

-

What are the demographic characteristics of students identified as LTELs? Are these demographic characteristics associated with English Language Development (ELD) test performance?

-

What are the profiles of LTELs in terms of domain subtest performances (i.e., listening, speaking, reading, writing) on a measure of their ELD? How are these profiles different for LTELs in special education or with LDs?

-

What is the impact of changing cut points, or removing domains, on the percent of LTELs who are eligible for reclassification? After changing the criteria for reclassification, what percent of the remaining LTELs are students in special education?

Method

Participants

This study conducted an analysis of an existing dataset collected by a large charter school organization in California and made available for this study. Most students attending these schools, about 70%, are Latinx and 17% are Black. Eight percent of students attending schools in this organization are students with disabilities, 28% are English Learners, and 78% of students attending these schools are from low-income families. The organization reports that they provide all legally required supports and programming for students identified as ELs or LTELs. More specific information about programming for ELs/LTELs at each school was not available.

Participants (N = 560) in this study were in grades 6th–12th. All students in the study were initially identified as ELs by their schools. In California, an EL is a student who meets the following criteria: his/her parent indicated a language other than English on a home language survey, and he/she does not meet proficiency on an English language proficiency test (CA Education Code Sect. 60810(d)). Additionally, the students in this study met the criteria to be identified as LTELs. In California, an LTEL has been enrolled in an American school for more than six years, has remained at the same English proficiency level on an English language development test for two or more years, and has scored below basic on a state-adopted English language arts standards-based test (California Assembly Bill No. 2193).

The dataset included school-reported LTEL status, grade level, gender, race/ethnicity, and eligibility for free/reduced-price lunch (FRL; an indicator of socioeconomic status, see Harwell & LeBeau, 2010). Data also included each student’s eligibility for special education and primary disability, if the student was in special education. Performance on the state-adopted ELD assessment at the time of data collection was also made available. Because this study conducted a secondary analysis of anonymized data collected by schools, it was considered exempt by the researchers’ Institutional Review Board.

Measure

Federal policy requires all students who are identified as ELs, including LTELs, take an annual test of English language development. In California, at the time of this study, this test was the California English Language Development Test (CELDT). The CELDT has four sections (i.e., Listening, Speaking, Reading, Writing), and students receive a score on each section, along with an overall score for the entire test. The CELDT is designed to measure the construct of English language proficiency, and it is aligned to the California ELD standards (CDE, 2013). The CELDT has five different versions for students in various grades: kindergarten/first grade, second grade, third through fifth grade, sixth through eighth grade, and ninth through twelfth grade. The entire test is untimed (CTB/McGraw-Hill, 2009). Students take the Listening, Reading, and Writing domains in a group administration, but the Speaking section of the test is administered one-on-one and scored by the examiner (CTB/McGraw-Hill, 2009).

For each student in the study, performance levels on each CELDT domain subtest were reported. CELDT performance levels range from 1 to 5 and are interpreted as follows: 1: Beginning, 2: Early Intermediate, 3: Intermediate, 4: Early Advanced, and 5: Advanced. Scale scores were not available. A Beginning level means the student has very limited receptive and/or productive English skills, ability to respond to communication, or use of oral and written language. Early Intermediate, Intermediate, Early Advanced, and Advanced levels indicate increasingly more accurate and complex receptive and/or productive language skills with reduced errors, with Advanced being the equivalent of a native English speaker.

Results

Relationships Between Performance and Student Characteristics

More than half (61%) of the LTELs in this study were male, and most students in the sample were eligible for FRL (84%). Almost all the LTELs in this study, 97%, were Latinx. Table 1 shows, in grades 6th–12th, the grade with the most LTELs was sixth grade (n = 172). With the exception of a slight rise in the number of LTELs in 10th grade, the number of LTELs dropped each year. Across all grades, 29% of LTELs (n = 160) were in special education, and most LTELs in special education, about 71%, were in special education identified with an LD (n = 113). The second most common category of disability for LTELs was Speech and Language Impairment (15%, n = 24). Table 1 also shows the percentage of LTELs with an LD increased most years. In 6th grade, only 15% of LTELs were students with an LD. However, by 12th grade, 47% of LTELs were also identified with an LD.

To examine the relationship between performance level on the ELD assessment and student gender, FRL status, and LD status, chi-square tests of homogeneity of groups were used. Specifically, we used a Pearson’s chi-square test with Yates’ continuity correction. Due to small cells with less than five students in some performance levels, two groups (i.e., 1: performance level 4 or 5, and 2: performance level 1, 2, or 3) of scores for each subtest were created.

A chi-square test of homogeneity of groups showed the relationships between gender and performance on the Reading (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 9.59, p < .01) and Writing (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 10.38, p < .01) subtests were significant. Gender was not significant for the Listening (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 1.05, p = .31) or Speaking (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 0.17, p = .68) subtests. Similarly, chi-square tests of homogeneity of groups showed significant relationships between eligibility for FRL and Reading (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 4.66, p < .05) and Writing (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 9.14, p < .01) subtests. The relationship between FRL and subtest performance levels was not significant for the Listening (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 2.64, p = .10) or Speaking (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 1.86, p = .17) subtests. To summarize, LTEL gender and eligibility for FRL are associated with performance on the Reading and Writing subtests but not associated with performance on the Listening or Speaking subtests.

To examine the relationship between performance level on this ELD assessment and LD status, we again used chi-square tests of homogeneity of groups. The analysis showed there were significant differences between LTELs with and without LDs on the ELD assessment subtests. On the Reading subtest, the relationship between LTEL LD status and Reading performance was significant (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 27.79, p < .001). Students’ results on the Writing subtest showed there was also a significant relationship between LD status and performance level (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 17.34, p < .001). Additionally, results of the Listening subtest showed there was a relationship between LD status and ELD performance level (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 4.82, p < .05), and there was also a significant relationship on the Speaking subtest (χ2 (1, N = 560) = 8.96, p < .01). Overall, these results indicate performance levels on this ELD assessment and LD status are not independent, and the performance levels on all four subtests are statistically associated with LD status.

LTEL ELD Performance by Domain

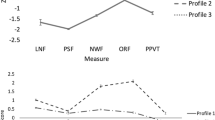

As shown in Fig. 1, for all students in the sample (N = 560), students performed best on the Listening and Speaking subtests, and many students were at a performance level 4 (Early Advanced) on these two subtests. On the other subtests, the most frequent performance level for all LTELs was 3, indicating many of these students were at an intermediate level on these skills. LTELs in special education (n = 160) differed from all LTELs on the most frequent performance level only on the Reading and Speaking subtests, and the most frequent score on these subtests was one performance level lower than the whole group of LTELs. As a group, LTELs with LDs scored poorly on the Reading subtest. On the Reading subtest, the most frequent performance level for LTELs with LDs was 1 (Beginning), indicating many of these students (37%) had Reading scores in the lowest performance level.

Impact of Restricting Domains on Reclassification Rates

For students to reclassify as English proficient, according to California Education code, students must have had an overall, or average, performance level of 4 or 5 on the State ELD assessment. Students may have a performance level 3 on one subtest, but the overall performance level must sum to higher. An analysis of the ELD scores in this study showed the school district used a compensatory model, rather than a conjunctive model, which allows some subtest scores to be below the standard (see Carroll & Bailey, 2016 for review). With this model, some LTELs who meet criteria for reclassification had a performance level 3 on one subtest, but all LTELs who meet reclassification criteria had an overall performance level of 4 or 5. In this sample, 35% of LTELs met the testing requirement to reclassify. Out of students who did not reclassify, 40% of these students were in special education.

As shown in Table 2, we explored the impact if there were to be a change in the requirements for reclassification. Given the overlap between reading and writing skills, and eligibility for special education with an LD, we explored the possibility of omitting the Reading and Writing subtests from the assessment. We found, for example, if students only needed to be at performance level of 3 or higher on both the Listening and Speaking subtests, most would reclassify. Of those who do not reclassify in this scenario, the majority of these students are in special education. In another scenario, if the test were again limited to Listening or Speaking, and students needed a performance level of 3 or above on either of these subtests, 97% would pass. In this scenario, out of the 18 students who do not meet these criteria, again, a majority of these students are in special education.

Discussion

This study examined a large data set from a single educational organization in one state to determine the second language development profiles of students who are LTELs. This study adds to the limited research on older students who remain classified as ELs (i.e., LTELs) during their middle and high school careers. Several important findings emerged from this study, and we summarize the results in the context of the three research questions below.

LTELs in Special Education

The percentage of LTELs in special education is worth discussing, especially since these rates are often unexamined or unreported in studies on students who are LTELs. The overall percentage of special education students in this sample of LTELs, 29%, is more than double the national percentage of 13%. This rate is similar to the rates found in the Thompson (2015) study, and this rate is especially high in these schools because only 8% of students in the charter school organization as a whole are in special education. A unique finding from this study is that the percentage of LTELs with an LD, as a proportion of all LTELs in a given grade, increased from sixth grade to twelfth grade. As a result, nearly 50% of LTELs who were still in the school system in twelfth grade were identified with an LD. The significant association between LD status and performance on all four ELD subtests suggests that characteristics common with LD status, dyslexia, for example, might explain why LTELs with LDs have a more difficult time meeting the criteria for reclassification.

Average ELD Scores on Subdomains

We found that LTELs are likely to perform better on assessments related to their listening and speaking abilities in English than on assessments related to their reading and writing abilities in English. These findings are consistent with other studies indicating that most LTELs have strong oral skills and relatively weaker reading and writing skills (e.g., Menken & Kleyn, 2010; Olsen, 2010). High average scores on the Listening and Speaking subtests suggest many LTELs have the necessary academic skills in oral language to reclassify, but their reading and writing skills are preventing them from being reclassified based on this assessment. Research has shown malleable factors such as instruction and reading strategies determine second language learners’ long-term literacy outcomes, but less so their oral language skills (Huang & Bailey, 2016). As a result, the lower literacy scores, but not the lower oral language scores, in this study are likely related to inadequate or inappropriate literacy instruction. Further, we know that many students who are not LTELs have a wide range of performances on English Language Arts (ELA) assessments, and so high levels of proficiency in English literacy may be indistinguishable from the constructs captured by ELA instruction and assessment. Thus, LTELs might perform similarly to students who are not LTELs on an ELD assessment, which undermines the utility and any unique contribution of the literacy subsection of ELD assessments with LTELs.

Impact of Changing Reclassification Criteria

ELD test scores at one time point indicate that about one-third of LTELs who take the ELD test meet criteria for reclassification each year. Narrowing the skills required for English proficiency to intermediate or higher levels of receptive and expressive oral language (i.e., limiting the assessment to the CELDT Listening and Speaking domains) has the effect of reclassifying most LTELs. Further supporting the idea of removing literacy from the assessment, the listening and speaking domains have been shown to differentiate ELs from English-only students much better than the reading and writing domains (CDE, 2011). The finding that most of the students who do not meet the criteria when the test only measures their listening and speaking skills in English are in special education suggests an underlying disability, and not exposure to English, is likely preventing more than a few LTELs from meeting the requirements for reclassification.

Implications

From a theoretical perspective, the number of students with an LTEL label suggests widely accepted theories of second language acquisition, which suggest ELs need between four and eight years of instruction to become academically proficient in English (Collier, 1987; Hakuta et al., 2000), may grossly underestimate the length of time it takes to acquire advanced proficiency in English. Possibly either theories of the academic English acquisition timeline are inaccurate or current methods for identifying LTELs are inadequate. Either way, the results from our study have important implications for instruction, assessment, and social justice.

Instructional Implications

The large number of LTELs in this study, and the growing number of LTELs in U.S. schools, indicate that ELD programs are not sufficient to help many ELs reach their academic potential. One reason for this might be that schools ignore students’ abilities in their home language, but this should not be the case. Instruction in the child’s home language is likely to reduce the achievement gap between ELs and their monolingual peers. However, most American schools only provide language instruction in English.

Cummins’ (1979) theory implies that, if American students have the opportunity to develop their first language, often Spanish, they are likely to transfer these skills to their second language, English. In fact, a long-standing review of research on language and reading instruction for ELs found that bilingual instruction leads to the best outcomes for ELs (Slavin & Cheung, 2005). Because students who are ELs can transfer their reading and language skills in their first language to English, first language development for native speakers, beginning in elementary school is beneficial (Klingner, et al., 2006; Olsen, 2010). Additionally, there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of bilingual interventions for elementary school students who are ELs (e.g., Calderón et al., 1998; Ginns et al., 2019).

Further, dedicated times for ELD are important. A study by Tong Lara-Alecio et al. (2008) showed that teaching ELD during a separate dedicated time improved ELD more than structured English immersion or teaching ELD integrated with content instruction throughout the day. Consequently, it might be necessary for schools to offer supplemental ELD classes outside of the school day (i.e., afterschool or over the summer) so ELs can narrow the gap between EL student achievement and non-EL student achievement (Hakuta et al., 2000).

For ELs who become LTELs, different interventions and instructional strategies are needed for these older students. Programs for LTELs need to be noticeably different from EL programs for new immigrants or ELs in elementary school (Olsen, 2010). These programs should include developmentally appropriate curriculum, and they should focus on both basic reading and writing, and more advanced skills like English grammar and syntax.

LTELs are likely to benefit from grade level, academic courses with their peers where their bilingualism is valued. Rather than ignoring their multilingual and translanguaging skills, which courses for LTELs tend to do, these skills should be leveraged in all classrooms to promote students’ academic language and literacy (e.g., Martínez, 2010) and take account of their linguistic, social, and cognitive development more broadly (Bailey & Orellana, 2015). These classes could also include discussions about the arbitrariness of Standard English, while also teaching the history and bias inherent in “curricularized” English (Delpit, 2006; Flores & Rosa, 2015; Kibler & Valdés, 2016).

Implications for School Psychologists

Another reason why LTELs might appear that they are still learning English is that they have an underlying disability, such as an LD. The results of this study suggest that LTELs are often students who struggle with reading and may have an LD, like dyslexia. It is possible that some students who come from a home where a language other than English is spoken end up labeled ELs and then become LTELs when they are unable to reclassify due to an undiagnosed LD.

Children are typically identified as ELs in kindergarten, but they are often not identified as students with LDs by a team that includes a school psychologist until several years later (Zehler et al., 2003). Despite later identification of an LD, there is evidence that children who go on to develop LDs show signs of this disability, especially on measures of phonological awareness and/or rapid naming, when they enter school (e.g., Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2017). Thus, ELs should be screened on these early predictors, and at-risk students should be provided early interventions starting in kindergarten or first grade (Lovett et al., 2017), before students are referred to special education.

For some ELs who are later identified with an LD, their challenges are primarily in reading—in any language, so an LD classification is likely more meaningful for receiving commensurate services than an EL classification alone. Although differentiating ELD issues from LDs can be difficult in early grades, it can be done. Researchers have expressed valid concerns about the assessments used to identify students who are ELs with LDs (Abedi, 2006; Artiles & Klingner, 2006; Ortiz, 2019). Addressing these concerns by deliberately choosing and interpreting assessments carefully (e.g., assessing students in both their home language and in English), and including an overview of students’ cultural assets (i.e., information from The Cultural Assets Identifier; Aganza et al., 2015) would allow students who are ELs to be holistically assessed for special education in early grades. Further, addressing the shortage of school psychologists who are specifically trained as bilingual school psychologists should be a priority (see Harris et al., 2020).

Implications for Testing English Learners

When children first enroll in school, they are typically identified as potential ELs by a home language survey (Bailey & Kelly, 2013). These surveys prompt parents to indicate which language their child most often hears at home, but it is important to note that these surveys are not designed to collect information on language proficiency. Instead, they serve to narrow down the pool of candidate students who are subsequently assessed for English proficiency at school intake (Bailey & Carroll, 2015). Because home language surveys and subsequent language proficiency assessments focus primarily on English, they provide incomplete information on children’s language skills, namely their proficiency in their first language. Proficiency in the first language is important because it is a predictor of proficiency in the student’s second language, in these cases, English (e.g., Anthony et al, 2009). Thus, for potential ELs, assessing their language skills in their home language would be helpful to identify students who are most at risk of becoming LTELs, because this may reveal, years sooner through their home language performance, whether a student could potentially have a diagnosis of an LD.

Although assessing students in their first language sounds like an insurmountable task for large school districts where students speak many different languages, assessing students in one or two additional languages might be sufficient. For example, in Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the student population speaks 93 different languages other than English. However, more than 93% of ELs in LAUSD speak Spanish (LAUSD, 2018). Thus, for most students in Los Angeles, assessing in both English and Spanish is not only more meaningful than testing in English only, it is also likely to be feasible.

Further, annual ELD testing for LTELs should be reevaluated. In this study, we found most LTELs have intermediate, or better, listening and speaking skills, so these skills might not need to be tested annually. LTEL reading and writing skills should be monitored, but it may not be necessary to do this using the annual summative ELD assessment. Rather than testing reading and writing skills on an ELD test, these skills could be measured and tracked using the same reading and writing classroom, formative assessments all the other students take, or more appropriately, with a specialized diagnostic tool if a disability is suspected, as mentioned previously. These skills can also be measured by portfolios filled with standards-based assessments (Siordia & Kim, 2021).

Implications for Social Justice

The vast majority of LTELs are marginalized, Spanish-speaking Latinx students. Even so, some LTELs’ first and most frequently used language is English (Flores et al., 2015; Hernandez, 2017; Kim and García, 2014). Nearly all, 97% in this study, of students with the LTEL label are Latinx students. To our knowledge, there is no other school-mandated test or label tied so closely to race/ethnicity. A stigmatizing label tied to testing that is so tightly linked to ethnicity and immigration status could add unnecessary stress for Latinx students. This kind of stress has been shown to negatively impact academic achievement (e.g., Vasquez-Salgado et al., 2018).

Although there are challenges when it comes to reclassifying LTELs, schools must rise to this challenge. Not only is the quality education of ELs ethically important, it is legally required. At the federal level, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR), requires schools to ensure that ELs “can participate meaningfully and equally in educational programs” (OCR, 2015). Additionally, the OCR requires that schools “ensure they achieve English language proficiency and acquire content knowledge within a reasonable period of time” (OCR, 2015). Even though ELs, and LTELs, are provided these protections by OCR, there is no guarantee that they will reach a level of English language proficiency suited to academic settings. This study provides some evidence that a significant number of ELs, who may already be part of a marginalized group, do not reach this level of proficiency in a timely manner. This is a social justice issue.

Limitations

Results of this correlational study must remain suggestive, and there are limitations to the data presented here. The students in this study all attended public charter schools, and students who attend charter schools might be different from students who attend traditional public schools. However, the number of students attending charter schools is growing rapidly. The percentage of students enrolled in public charter schools has more than tripled since 2000 (McFarland et al., 2018), which highlights the importance of examining the performance of students who attend these schools. Another limitation of this study is the language measure. The CELDT is specific to California, and ELD tests vary from state to state. Thus, these results might not hold for other states. Additionally, ELD assessments are often in a state of flux with next-generation assessments being developed by states and assessment consortia. In California, for example, the CELDT has been replaced with a different standardized test of English Language development. Although new test formats and questions are different, these tests continue to measure the same skills (i.e., expressive and receptive language skills in English), which are aligned with state ELD standards and federal requirements. Further, many states (i.e., the 39 states using the ACCESS for ELs 2.0 ELD assessment) put even more emphasis on reading and writing skills than the California assessment examined here. In these states, ELs and LTELs reading and writing skills make up 70% of the students’ overall assessment score, while listening and speaking are only weighted 30% of the overall score (Bauman et al., 2007). This highlights the importance of the current findings for reexamining the role of literacy on the impact of reclassifying ELs elsewhere as well. Despite some limitations, this study is unique in that the sample size is fairly large, which is uncommon for a study of students who are LTELs, and the sample includes students in special education. Special education students are often excluded from studies of ELs and LTELs, and the findings here add to the limited research on students who are identified as both LTELs and students in special education.

Conclusion

Like much of the research on students who are acquiring English in school that has focused on achievement gaps, rather than on the linguistic and academic assets of these students (Jensen et al., 2018), the research on LTELs tends to focus primarily on their academic failures and ignores their strengths (Callahan, 2005; Short & Fitzsimmons, 2007). This study aims to shift the focus to these students’ strengths. In doing so, we acknowledge the limitations of the LTEL label. We agree with Callahan and Shifrer (2016) that, “[i]t would be a stretch to suggest that long-term EL status indicates limited familiarity with the English language or the U.S. educational system….[instead] this phenomenon may be the result of a particularly onerous equity trap” (p. 488). We also agree with Kibler and Valdés (2016), who push back against the use of this label—a term that, among other things, “does not reflect the complexity of current language acquisition theories [and] places the focus on ‘English’ to the exclusion of other factors influencing the learner in a minoritized context” (p. 110).

The fact that most LTELs are proficient in understanding and speaking English, as shown by scores on ELD tests here, suggests that these students could be considered largely fluent in oral English, and the lower reading and writing scores are probably better explained by subtractive schooling and inadequate interventions that can impact most students in high poverty schools, not just students who come from a home where a language other than English is spoken. For a significant number of students labeled LTELs, their learning disabilities are the likely reason they continue to struggle on the reading and writing ELD subtests grade after grade, which prevents them from being reclassified. In either of these situations, classes and supports where students’ culture and home language are valued would be helpful. With this kind of effective support, many more students who are ELs are likely to avoid the LTEL label and better reap the cognitive and social benefits associated with bilingualism (Adesope et al., 2010).

References

Abedi, J. (2006). Psychometric Issues in the ELL Assessment and Special Education Eligibility. Teachers College Record, 108(11), 2282–2303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00782.x

Adesope, O. O., Lavin, T., Thompson, T., & Ungerleider, C. (2010). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Cognitive Correlates of Bilingualism. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 207–245. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310368803

Aganza, J. S., Godinez, A., Smith, D., Gonzalez, L. G., & Robinson-Zañartu, C. (2015). Using cultural assets to enhance assessment of Latino students. Contemporary School Psychology, 19(1), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-014-0041-7

Anthony, J. L., Solari, E. J., Williams, J. M., Schoger, K. D., Zhang, Z., Branum-Martin, L., & Francis, D. J. (2009). Development of bilingual phonological awareness in Spanish-speaking English language learners: The roles of vocabulary, letter knowledge, and prior phonological awareness. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(6), 535–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430903034770

Artiles, A. J., & Klingner, J. K. (2006). Forging a Knowledge Base on English Language Learners with Special Needs: Theoretical, Population, and Technical Issues. Teachers College Record, 108(11), 2187–2194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00778.x

Bailey, A. L., & Carroll, P. E. (2015). Assessment of English language learners in the era of new academic content standards. Review of Research in Education, 39(1), 253–294. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X14556074

Bailey, A. L., & Kelly, K. R. (2013). Home language survey practices in the initial identification of English learners in the United States. Educational Policy, 27(5), 770–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904811432137

Bailey, A., & Orellana, M. F. (2015). Adolescent development and everyday language practices: Implications for the academic literacy of multilingual learners. In D. Molle, E. Sato, T. Boals, & C. A. Hedgspeth (Eds.), Multilingual learners and academic literacies: Sociocultural contexts of literacy development in adolescents (pp. 53–74). Routledge.

Bauman, J., Boals, T., Cranley, E., Gottlieb, M., & Kenyon, D. (2007). Assessing comprehension and communication in English state to state for English language learners (ACCESS for ELLs®). English language proficiency assessment in the nation: Current status and future practice, 81–91. Retrieved from https://www.nsbsd.org/cms/lib/AK01001879/Centricity/Domain/781/ACCESS%20Interpretive%20Guide%202012.pdf

Brooks, M. D. (2015). “It’s Like a Script”: Long-Term English Learners’ Experiences with and Ideas about Academic Reading. Research in the Teaching of English, 49(4), 383–406.

Brooks, M. D. (2016). “Tell me what you are thinking”: An investigation of five Latina LTELs constructing meaning with academic texts. Linguistics & Education, 35, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2016.03.001

Calderón, M., Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., & Slavin, R. (1998). Effects of bilingual cooperative integrated reading and composition on students making the transition from Spanish to English reading. The Elementary School Journal, 99(2), 153–165. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1002107

California Department of Education (2011) A Comparison Study of Kindergarten and Grade 1 English-Fluent Students and English Learners on the 2010–11 Edition of the CELDT. Morgan Hill, California: Educational Data Systems. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/be/pn/im/documents/imadaddec11item02a1.pdf

California Department of Education (2013). California English Language Development Test Item Alignment to the 2012 English Language Development Standards Report. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/el/

California Department of Education. (2021) English Learner Population in California Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sg/englishlearner.asp

Callahan, R. M. (2005). Tracking and High School English Learners: Limiting Opportunity to Learn. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 305–328. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312042002305

Callahan, R., & Shifrer, D. (2016). Equitable Access for Secondary English Learner Students. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(3), 463–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X16648190

Callahan, R., Wilkinson, L., & Muller, C. (2010). Academic Achievement and Course Taking Among Language Minority Youth in U.S. Schools: Effects of ESL Placement. Educational Evaluation & Policy Analysis, 32(1), 84–117. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373709359805

Carroll, P., & Bailey, A. L. (2016). Do decision rules matter? A descriptive study of English language proficiency assessment classifications for English-language learners and native English speakers in fifth grade. Language Testing, 33(1), 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532215576380

U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). Quick Facts: Language other than English spoken at home, percent of persons age 5 years+, 2013–2017. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US#

Collier, V. P. (1987). Age and rate of acquisition of second language for academic purposes. TESOL Quarterly, 21, 617–641. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586986

Cosentino, d. C., Deterding, N., & Clewell, B. C. (2005). Who’s left behind? immigrant children in high and low LEP schools.The Urban Institute, 2100 M St., NW, Washington, DC 20037. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED490928.pdf

CTB/McGraw-Hill. (2009). Technical report for the California English Language Development Test (CELDT) 2008–09 Edition. Report submitted to the California Department of Education on October 30, 2009. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/el/techreport.asp

Dabach, D. B. (2014). “I Am Not a Shelter!”: Stigma and Social Boundaries in Teachers’ Accounts of Students’ Experience in Separate “Sheltered” English Learner Classrooms. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 19(2), 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2014.954044

Delpit, L. (2006). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. The New Press.

Ehrhardt, J., Huntington, N., Molino, J., & Barbaresi, W. (2013). Special education and later academic achievement. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e31827df53f

Flores, N., Kleyn, T., & Menken, K. (2015). Looking holistically in a climate of partiality: Identities of students labeled long-term english language learners.Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 14(2), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2015.1019787

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149–171.

Gandara, P. (2010). Overcoming Triple Segregation. Educational Leadership, 68(3), 60–64.

Ginns, D. S., Joseph, L. M., Tanaka, M. L., & Xia, Q. (2019). Supplemental phonological awareness and phonics instruction for Spanish-speaking English Learners: Implications for school psychologists. Contemporary School Psychology, 23(1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-018-00216-x

Hakuta, K., Butler, Y. G., & Witt, D. (2000). How Long Does It Take English Learners To Attain Proficiency? University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute. Policy Report 2000–1. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED443275.pdf

Harris, B., Vega, D., Peterson, L. S., & Newell, K. W. (2020). Critical Issues in the Training of Bilingual School Psychologists. Contemporary School Psychology, 1-15.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00340-7

Hernandez, S. J. (2017). Are They All Language Learners?: Educational Labeling and Raciolinguistic Identifying in a California Middle School Dual Language Program. CATESOL Journal, 29(1), 133–154.

Hill, L. E., Weston, M., & Hayes, J. M. (2014). Reclassification of English learner students in California. Public Policy Institute of California. Retrieved from https://www.ppic.org/publication/reclassification-of-english-learner-students-in-california/

Huang, B. H., & Bailey, A. L. (2016). The Long-Term English Language and Literacy Outcomes of First-Generation Former Child Immigrants in the United States. Teachers College Record, 118(11).

Jensen, B., Grajeda, S., & Haertel, E. (2018). Measuring cultural dimensions of classroom interactions. Educational Assessment, 23(4), 250–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2018.1515010

Kanno, Y., & Cromley, J. G. (2013). English language learners’ access to and attainment in postsecondary education. Tesol Quarterly, 47(1), 89–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.49

Kanno, Y., & Kangas, S. E. N. (2014). “I’m not going to be, like, for the AP”: English language learners’ limited access to advanced college-preparatory courses in high school. American Educational Research Journal, 51(5), 848–878. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214544716

Kibler, A. K., & Valdés, G. (2016). Conceptualizing language learners: Socioinstitutional mechanisms and their consequences. Modern Language Journal, 100, 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12310

Kibler, A. K., Karam, F. J., Ehrlich, V. A. F., Bergey, R., Wang, C., & Elreda, L. M. (2018). Who Are “Long-term English Learners”? Using Classroom Interactions to Deconstruct a Manufactured Learner Label. Applied Linguistics, 39(5), 741–765. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw039

Kim, W. G., & García, S. B. (2014). Long-term English language learners’ perceptions of their language and academic learning experiences. Remedial and Special Education, 35(5), 300–312.

Klingner, J. K., Artiles, A. J., & Barletta, L. M. (2006). English Language Learners Who Struggle With Reading Language Acquisition or LD? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(2), 108–128.

Linklater, D. L., O’Connor, R. E., & Palardy, G. J. (2009). Kindergarten literacy assessment of english only and english language learner students: An examination of the predictive validity of three phonemic awareness measures. Journal of School Psychology, 47(6), 369–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2009.08.001

Los Angeles Unified School District (2018) 2018 Master Plan for English Learners and Standard English Learners. Los Angeles, California: Los Angeles Unified School District Division of Instruction, Multilingual and Multicultural Education Department. Retrieved from https://achieve.lausd.net/cms/lib/CA01000043/Centricity/domain/22/el%20sel%20master%20plan/2018%20Master%20Plan%20for%20EL%20and%20SEL.pdf

Lovett, M. W., Frijters, J. C., Wolf, M., Steinbach, K. A., Sevcik, R. A., & Morris, R. D. (2017). Early intervention for children at risk for reading disabilities: The impact of grade at intervention and individual differences on intervention outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(7), 889–914. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000181

Martínez, R. A. (2010). “Spanglish” as Literacy Tool: Toward an Understanding of the Potential Role of Spanish-English Code-Switching in the Development of Academic Literacy. Research in the Teaching of English, 124–149.

McFarland, J., Hussar, B., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Wang, K., Rathbun, A., Barmer, A., Forrest Cataldi, E., and Bullock Mann, F. (2018). The Condition of Education 2018 (NCES 2018–144). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018144.pdf

Menken, K., & Kleyn, T. (2010). The long-term impact of subtractive schooling in the educational experiences of secondary English language learners. International Journal of Bilingual Education & Bilingualism, 13(4), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050903370143

Menken, K., Kleyn, T., & Chae, N. (2012). Spotlight on “long-term English language learners”: Characteristics and prior schooling experiences of an invisible population. International Multilingual Research Journal, 6(2), 121–142.

Office for Civil Rights. (2015). Ensuring English Learner Students Can Participate Meaningfully and Equally in Educational Programs [Fact sheet]. U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/dcl-factsheet-el-students-201501.pdf

Olsen, L. (2010). Reparable Harm: Fulfilling the Unkept Promise of Educational Opportunity for California’s Long Term English Learners. Long Beach, CA: Californians Together. Retrieved from http://www.ctdev.changeagentsproductions.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ReparableHarm2ndedition.pdf

Ortiz, S. O. (2019). On the measurement of cognitive abilities in English learners. Contemporary School Psychology, 23(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-018-0208-8

Ozernov-Palchik, O., Norton, E. S., Sideridis, G., Beach, S. D., Wolf, M., Gabrieli, J. D., & Gaab, N. (2017). Longitudinal stability of pre-reading skill profiles of kindergarten children: Implications for early screening and theories of reading. Developmental Science, 20(5), e12471. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12471

Rojas, R., & Iglesias, A. (2013). The Language Growth of Spanish-Speaking English Language Learners. Child Development, 84(2), 630–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01871.x

Samson, J. F., & Lesaux, N. K. (2009). Language-minority learners in special education: Rates and predictors of identification for services. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(2), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219408326221

Shin, N. (2020). Stuck in the middle: Examination of long-term English learners. International Multilingual Research Journal, 14(3), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2019.1681614

Shore, J. R., & Sabatini, J. (2009). English language learners with reading disabilities: A review of the literature and the foundation for a research agenda. ETS Research Report Series, 2009(1), i-48.Retreived from https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-09-20.pdf

Short, D., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2007). Double the work: Challenges and solutions to acquiring language and academic literacy for adolescent English language learners: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education. Retrieved from https://www.carnegie.org/publications/double-the-work-challenges-and-solutions-to-acquiring-language-and-academic-literacy-for-adolescent-english-language-learners/

Siordia, C., & Kim, K. M. (2021). How language proficiency standardized assessments inequitably impact Latinx long‐term English learners. TESOL Journal, e639. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.639

Slama, R. B. (2014). Investigating whether and when English learners are reclassified into mainstream classrooms in the United States: A discrete-time survival analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 51(2), 220–252. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214528277

Slavin, R. E., & Cheung, A. (2005). A synthesis of research on language of reading instruction for English language learners. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 247–284. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075002247

Solari, E. J., Petscher, Y., & Folsom, J. S. (2014). Differentiating literacy growth of ELL students with LD from other high-risk subgroups and general education peers: Evidence from grades 3–10. Journal of Learning Disabilities (austin), 47(4), 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219412463435

Thompson, K. D. (2015). Questioning the Long-Term English Learner Label: How Categorization Can Blind Us to Students’ Abilities. Teachers College Record, 117(12), n12.

Tong, F., Lara-Alecio, R., Irby, B., Mathes, P., & Kwok, O. M. (2008). Accelerating early academic oral English development in transitional bilingual and structured English immersion programs. American Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 1011–1044. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208320790

U.S. Department of Education, Office of English Language Acquisition. (2017) “Our Nation’s English Learners.” Retrieved January 15, 2022. https://www2.ed.gov/datastory/el-characteristics/index.html#datanotes

Vasquez-Salgado, Y., Ramirez, G., & Greenfield, P. M. (2018). The impact of home-school cultural value conflicts and president trump on Latina/o first-generation college students’ attentional control. International Journal of Psychology : Journal International De Psychologie, 53(Suppl 2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12502

Yang, H., Urrabazo, T., & Murray, W. (2001). How Did Multiple Years (7+) in a BE/ESL Program Affect the English Acquisition and Academic Achievement of Secondary LEP Students? Results from a Large Urban School District. Dallas, TX: Dallas Independent School District. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED452709.pdf

Zehler, A. M., Fleischman, H. L., Hopstock, P. J., Stephenson, T. G., Pendzick, M. L., & Sapru, S. (2003). Descriptive study of services to LEP students and LEP students with disabilities. Policy report: Summary of findings related to LEP and SPED-LEP students. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ncela.ed.gov/files/rcd/BE021199/special_ed4.pdf

Funding

Partial financial support was received from the University of California, Los Angeles in the form of a Graduate Summer Research Mentorship Program stipend.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rhinehart, L.V., Bailey, A.L. & Haager, D. Long-term English Learners: Untangling Language Acquisition and Learning Disabilities. Contemp School Psychol 28, 173–185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-022-00420-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-022-00420-w