Abstract

If a decision context is completely precise, making good decisions is relatively easy. In the presence of ambiguity, rational decision-making is incomparably more challenging. We understand ambiguous situations as cases, where the decision-maker has imprecise (uncertain or vague) knowledge that is acquired from incomplete information (without limiting it to probability judgements as in common terminology). From that, we assume that imprecisions in knowledge can affect all elements of the decision field as well as the objective function. For the modeling of such decision situations, classical logics are no longer considered as means of choice, so that we suggest using approaches from the field of multi-valued logic. In the present work, we take suitable calculi from the so-called intuitionistic fuzzy logic into account. On that basis, we propose a model for the formulation and solving of decision problems under ambiguity (in the general sense). Particularly, we address decision situations, in which a decision-maker has sufficient information to specify point probability values, but insufficient information to express point utility values. Our approach is also applicable for modeling cases in which the probability judgments or both, probability and utility judgements are imprecise. Our model is novel in that we combine core elements of established approaches for the formal handling of uncertainty (maxmin and \( \alpha \)-maxmin expected utility models) with the mathematical foundation of intuitionistic fuzzy theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Theories of rational decision-making behavior under uncertainty have always been central subjects in prescriptive decision theory. Bernoulli’s work (1738)Footnote 1 with its later axiomatization by von Neumann and Morgenstern (1947) forms the theoretical basis of rational behavior in decisions under risk, the expected utility theory (EU). It proposes that if a decision-maker’s preferences concerning risky alternatives fulfill a set of well-defined axioms, a utility function can be derived. This function assigns a real number to the consequences of each alternative in every state of nature. It reflects the decision-maker’s attitude towards the consequence values as well as his or her attitude towards risk. The sum of the probability weighted single utilities for each alternative determines their respective expected utility values. According to the theory, a rational decision-maker maximizes his or her utility by choosing the alternative with the highest expected utility value. EU and the underlying axioms do not focus on the question of how the decision-relevant state probabilities are determined. This aspect is much more a subject of subjective expected utility theory (SEU). It postulates conditions, under which probabilities can be derived from preference statements. Its axiomatic foundation is attributed to Savage (1954) and is accounted as one of the most important approaches for rational decision-making under risk.

Equally as important are the innumerable studies concerning behavioral violations of corresponding axioms; primarily, because they reveal the limits of rationality-forming theories and thus claim to provide proof of irrational behavior by decision-makers, who act inconsistently to them. The latter described efforts are often to be found in the literature, especially when it comes to violations of the rationality postulates of SEU in decision situations that are (at least partially) ambiguous. The concept of ambiguity has different interpretations in the literature, whereas the most common definitions and types can be ascribed to incomplete information on probabilities (see e.g., Franke 1978; Curley et al. 1986; Frisch and Baron 1988; Camerer and Weber 1992; Fox and Tversky 1995; Ghirardato et al. 2004). This terminology receives an increased scientific attention due to the work of Ellsberg (1961), who provides evidence for violations of Savage’s axioms in decision situations under ambiguity. This kind of decision problems, which Ellsberg characterizes as situations between “complete ignorance” and “risk”, attracts many researchers and results in a tremendous follow-up research. It mainly focusses on the description of behavioral inconsistencies regarding both preference-building mechanisms and probabilistic requirements of SEU (see e.g., Slovic and Tversky 1974; Einhorn and Hogarth 1986; Kahn and Sarin 1988; Curley and Yates 1989; Kunreuther et al. 1995).

The ever-increasing amount of empirical results supporting Ellsberg’s findings gives rise to another research stream, which develops a more critical view to most of these insights. While some of the corresponding works solely question the necessity and sufficiency of common rationality axioms as foundation for rational behavior, some other try to present approaches for a formal handling of inconsistencies with the rationality axioms in decision situations with ambiguous probability assessments. Particularly, the application of non-additive measures for the modeling of ambiguity settings has achieved great recognition in decision theory since the corresponding contributions by Schmeidler (1989) and Gilboa and Schmeidler (1989). By modifying the axioms of SEU, Schmeidler (1989) elaborates a subjective, non-additive measure based approach that can be applied to define ambiguity attitudes and formally handle inconsistencies with selected axioms of rational behavior. He uses Choquet’s (1954) theoretical basis of non-additive capacities. Therefore, the corresponding theory is called Choquet expected utility theory (CEU). While in CEU the decision-maker’s beliefs regarding the occurrence of states are expressed by non-additive probability substitutes (unique priors), in Gilboa’s and Schmeidler’s (1989) maxmin expected utility model (MEU) decision-maker’s beliefs are represented by a set of probabilities (multiple priors). Under consideration of Wald’s (1949) maxmin rule, it is a pessimistic approach, which suggests selecting the alternative with the highest minimum expected utility value. By supplementing aspects of the Hurwicz criterion (1951), Ghirardato et al. (2004) have established the \( \alpha \)-maxmin expected utility model (\( \alpha \)-MEU). In accordance to MEU, \( \alpha \)-MEU assumes that decision-maker’s beliefs are represented by a set of probabilities. For decision-making, the overall expected utility is calculated as the weighted average of maximum and minimum expected utility for each alternative. Within this approach, the weights are understood as expressions of the decision-maker’s attitude towards ambiguity.Footnote 2 Al-Najjar and Weinstein (2009) provide a critical review of related approaches that were elaborated during the following two decades after Gilboa’s and Schmeidler’s initial work. A broader overview of related research contributions is given by Gilboa and Marinacci (2016).

The work mentioned previously, primarily deals with the relaxation of axiomatic demands on decision-makers, regarding the formation of their preferences and probability judgments. Other than that, there are approaches, which rather deal with the formal structure of imprecise knowledge, and its handling within corresponding decision problems. Significant theories to mention in this context are theories of fuzzy measures and fuzzy sets, initially introduced by Zadeh (1965, 1978). While fuzzy measure theory is primarily concerned with the analysis of alternative measures to the stringently axiomatized probability measure, the fuzzy set theory mainly provides tools for the mathematical modeling of imprecisions with respect to all possible components of the decision field (for discussion, see Metzger and Spengler 2017). The latter mentioned theories have great potential for the formulation of decision problems in which the decision-maker is faced with vague or incomplete information; in particular, because vague or incomplete information has a major impact on corresponding rationality considerations. We suggest not only reducing these to inconsistencies concerning probability judgements and preference statements, but rather focus on potential behavioral effects resulting from imperfect information. In this context, we want to refer to the following statement given by Gilboa and Marinacci (2016):

[…] (T)he (traditional) axiomatic foundations […] are not as compelling as they seem, and […] it may be irrational to follow this approach. […] (It) is limited because of its inability to express ignorance: it requires that the agent express beliefs whenever asked, without being allowed to say “I don’t know”. Such an agent may provide arbitrary answers, which are likely to violate the axioms, or adopt a single probability and provide answers based on it. But such a choice would be arbitrary, and therefore a poor candidate for a rational mode of behavior.

We support this statement to the fullest and are strongly convinced, that this problem also appears, when a decision-maker is asked to determine (point) utility values. Subsequently, the question arises, whether the previously presented models can actually handle these limitations of (S)EU when it comes to determine rational decision behavior. From our previous discussion it follows that they are able to handle limitations of (S)EU, but only those associated with vague probability statements. Vagueness, that affects other components of the decision field, is not treated by these approaches. Additionally, all of them generate other requirements the decision-maker has to fulfill in order to apply these models in respective decision-making contexts. In this regard, we want to extend the theoretical analysis of (ir-) rational decision-making under incomplete information. Therefore, we specify our understanding of rationality and apart from that generalize the definition of ambiguity compared to the narrow one manifested by Ellsberg (1961). On that basis, we propose an approach for the formal handling of ambiguity in the general sense, including instruments of intuitionistic fuzzy theory.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we first describe our comprehension of the rationality and ambiguity terms in relation to our approach. In Sect. 3, we provide theoretical and terminological basics for the method that underlies to our approach. In Sect. 4, we introduce our model and illustrate it with a numerical example. In Sect. 5, we conclude with a discussion on our results and implications for future research.

2 Understanding of ambiguity and rationality within our approach

Considering its etymology, rational behavior is reasonable and thoughtful behavior, while emotional behavior is one arising from intense and temporary mind movements. As long as people (and not machines) make decisions, they are always more or less emotional. Emotions thus accompany rational decisions, so that the interpretation as opposing concepts does not hit the core. In rationality concepts that are constructed bipolar, “irrational” is the opposite of “rational” et vice versa, and “rational” is the opposite of “emotional” et vice versa. In contrast to bipolar constructs, we assume here the possibility of complete independence (orthogonality) of rationality, irrationality, and emotionality, which may—but do not have to—be present within actions of an individual. Thus, it is possible for the decision-maker to show rational behavior for some components of the decision, and irrational as well as emotional behavior for others. For illustration, imagine a decision-maker that has to conduct calculations in order to obtain a reasonable solution for a decision problem. This individual accounts calculations as satisfying and generally enjoys it. During this calculation procedure, he or she makes an unconscious mistake and on that basis takes the wrong decision. In this case, the procedure itself would be rational and also emotional to some degree. Due to the mistake in the calculations, the result would be also irrational at the same time.

Constructing all three dimensions orthogonally, for which we want to plead here, the overall interrelation can be illustrated graphically in the form of a cube (Fig. 1).

The notion of ambiguity is mainly of Latin (later also French) origin and generally means equivocation (see e.g., Ries 1994). In decision-logic contexts, which we are essentially concerned with here, this addresses the equivocation of elements of the decision field and the objective function. This in turn can refer to alternatives, consequences, environmental states and probability judgements on the one hand and (above all) to the preference function on the other hand. Therefore, we propose to understand ambiguous situations as general cases, where the decision-maker has imprecise (uncertain or vague) knowledge that is acquired from incomplete information (without limiting it to probability judgements). From that, we assume that imprecisions in knowledge can affect all elements of the decision field. This understanding of ambiguity goes beyond the terminology and conceptualization as introduced by Ellsberg (1961). Extensive discourses on ambiguity in the broader sense are provided by, e.g., Furnham and Ribchester (1995), Furnham and Marks (2013), McLain, Kefallonitis, and Armani (2015) and Lauriola et al. (2016). How an individual deals with ambiguity depends on his or her ambiguity attitudes (see e.g., Budner 1962; McLain 1993). We will come back later to the particular impact of ambiguity attitudes within decision situations.

If the decision context is completely precise, making good decisions is relatively easy. In the case of ambiguity, rational decision-making is incomparably more difficult, irrespective of the degree of irrationality and emotionality. Classical logics are then no longer considered as means of choice, so that one is well advised to use approaches from the field of multi-valued logic. The term ‘multi-valued logic’ describes all logical concepts that do not satisfy the bivalence principle and therefore have more than two truth values, in contrast to two-valued logic, which allows something only being true (= 1) or false (= 0) (see e.g., Dubois and Prade 1980; Gottwald 2006). In the present work, we take suitable calculi from the so-called intuitionistic fuzzy logic into account.

3 Fuzzy theory and intuitionistic fuzzy theory and terminology basics

The foundation of our approach is Atanassov’s (1986) intuitionistic fuzzy set theory (or i-fuzzy-, for short), which in the past decades has received increasing scientific attention as extension of Zadeh’s (1965) fuzzy set theory.

The starting point of our model is the construct of a fuzzy set (in the following we call it traditional fuzzy set) as introduced by Zadeh (1965). Let \( X \) be a finite classical set with its elements \( x \). A corresponding fuzzy set \( \tilde{A} \) is determined by assigning to each \( x \in X \) a value \( \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} (x) \in \left[ {0, 1} \right] \) that expresses the membership degree of the elements \( x \) to this fuzzy set \( \tilde{A} \). The higher the membership degree \( \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} (x) \), the more element x belongs to \( \tilde{A} \). Structurally we get a set containing ordered pairs, \( \tilde{A} = \left\{ {\left( {x, \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} (x)} \right)\, |\, x \in X} \right\} \), where \( \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} \) represents a set function with \( \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} :X \to \left[ {0, 1} \right] \). We want to illustrate this approach by the following example (Spengler 2015): A manager wants to assess his or her satisfaction with potential annual profit levels. Applying the traditional fuzzy set approach, (s)he first has to formulate a classical set \( X \) with realizable profit values \( x \). This example set may contain the following elements (in thousand €): \( X = \left\{ {100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600} \right\} \). Subsequently (s)he has to assess to what extent each potential annual profit level \( x \in X \) satisfies him or her. In the sense of traditional fuzzy set theory, the manager assesses to which degree \( \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} (x) \) the annual profit values belong to the fuzzy set \( \tilde{A} \) of satisfactory profits. Here, \( \tilde{A} \) formally represents the fuzzy statement “\( x \) is a satisfactory annual profit level” and exemplarily can appear as follows:

While traditional fuzzy set theory does not specify how to interpret the inverse membership degree \( 1 - \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} (x) \), Atanassov (1986) makes this aspect to a core research subject within his i-fuzzy set theory. He proposes a further differentiation of \( 1 - \mu_{{\tilde{A}}} (x) \) by introducing a degree of non-membership and a degree of indeterminacy, which enable a decision-maker to undertake a much stronger content-related and formal information differentiation. Furthermore, this approach provides a sophisticated basis for representation of ambiguous knowledge, which allows us to describe real decision problems in a more appropriate way.

But what is intuitionistic about Atanassov’s i-fuzzy sets? The concept of intuition is essentially based on the Latin noun intuitio (= the immediate contemplation). Intuitive assessments are based more on afflatus or anticipated grasp (“from the gut”) and less on scientifically discursive justifications (see e.g., Dorsch et al. 1994). While classical logics (e.g.) are based on the bivalence principle, according to which a statement is either clearly true or clearly false, more than two (truth) values are allowed in non-classical (multi-valued) logics. The latter includes intuitionistic logic (Brouwer 1913).Footnote 3 This logic is not about truth functionality, but about the question of whether \( A \vee \neg A \) can be proved. Consequently, the law of excluded middle does not apply in it, just as it does not apply in fuzzy logic (see e.g., Dubois and Prade, 1985). An extension of the intuitionistic logic is the intuitionistic fuzzy logic (see e.g., Takeuti and Titani 1984; Atanassov 1999). In the present work, we want to use i-fuzzy sets in Atanassov’s sense, so that the interesting terminological discourse between Atanassov (2005) and Dubois et al. (2005) is only marginally mentioned here.

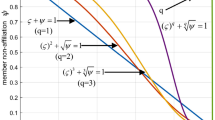

In contrast to the notation used in traditional fuzzy set theory, we denote an intuitionistic fuzzy set by \( \hat{A} \). Having a finite set \( X \) with its elements \( x \), we now can assign to each element \( x \) a membership degree \( \mu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \) \( \in \left[ {0, 1} \right] \), a non-membership degree \( \nu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \) \( \in \left[ {0, 1} \right] \), and degree \( \pi_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \), where \( \pi_{{\hat{A}}} (x) = 1 - \mu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) - \nu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \). \( \pi_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \) represents the degree of indeterminacy regarding the (non-) membership of the element \( x \) to the i-fuzzy set \( \hat{A} \). These structurally form a set of ordered triplets with the following definition: \( \hat{A} = \left\{ {(x, \mu_{{\hat{A}}} (x),\nu_{{\hat{A}}} (x)) \,|\, x \in X} \right\} \). In this standard notation, the degree of indeterminacy is not explicitly noted. It implicitly results from the subtraction mentioned above. From this notation also can be derived, that if \( \pi_{{\hat{A}}} (x) = 0 \) then \( \nu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) = 1 - \mu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \). In this case, we again have a traditional fuzzy set definition. It follows, that traditional fuzzy sets are special cases of i-fuzzy sets.

Considering the intuitionistic fuzzy approach within our previous example, in addition to assessing its satisfaction with profit levels \( x \in X \), the manager may indicate to what extent (s)he does not account them as satisfying. For this (s)he has to determine the degree \( \nu_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \), to which (s)he is dissatisfied with the single profit values. If (to a certain degree) (s)he is not sure, how (dis-) satisfying the profit levels are, (s)he also can specify a degree \( \pi_{{\hat{A}}} (x) \). The corresponding i-fuzzy set \( \hat{A} \) exemplarily can appear as follows: \( \hat{A} = \left\{ {\left( {100, 0.2, 0.8} \right), \left( {200, 0.3, 0.5} \right), \left( {300, 0.5, 0.4} \right), \;\left( {400, 0.7, 0.2} \right), \left( {500, 0.8, 0.1} \right), \left( {600, 1} \right)} \right\} \). In this paper we want to focus on constructs called intuitionistic fuzzy values (or i-fuzzy values, for short), which are strongly interrelated with the i-fuzzy set concept. Based on the above defined i-fuzzy sets, \( \alpha (x) = \left( {\mu_{\alpha } (x), \nu_{\alpha } (x)} \right) \) is called i-fuzzy value, where \( \mu_{\alpha } (x) \in \left[ {0, 1} \right] \), \( \nu_{\alpha } (x) \in \left[ {0, 1} \right] \) and \( \mu_{\alpha } (x) + \nu_{\alpha } (x) \le 1 \). The degree \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) \) with \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) = 1 - \mu_{\alpha } (x) - \nu_{\alpha } (x) \) maps the indeterminacy of the decision-maker when evaluating an element \( x \) with respect to a defined attribute. In the following, we use the triple notation of an i-fuzzy value in the form \( \alpha (x) = \left( {\mu_{\alpha } (x),\nu_{\alpha } (x), \pi_{\alpha } (x)} \right) \) (see e.g., Xu and Yager 2009).

To illustrate possible geometrical representations of i-fuzzy values, we go back to the example of the manager, who wants to assess his or her satisfaction with potential annual profit levels. In this context, we “translate” the previously deduced elements of i-fuzzy set \( \hat{A} \) into i-fuzzy values. From that we get six i-fuzzy values \( \alpha (100) = (0.2, 0.8, 0) \), \( \alpha (200) = (0.3, 0.5, 0.2) \), \( \alpha (300) = (0.5, 0.4, 0.1) \), \( \alpha (400) = (0.7, 0.2, 0.1) \), \( \alpha (500) = (0.8, 0.1, 0.1) \) and \( \alpha (600) = (1, 0, 0) \), which can be geometrically represented in an \( MNO \)-triangle (Fig. 2) as suggested by Szmidt and Kacprzyk (2010). \( M \), \( N \) and \( O \) are the corner points of the triangle, where, respectively, one of the elements \( \mu_{\alpha } (x) \), \( \nu_{\alpha } (x) \) or \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) \) equals 1 and the other two elements are equal to zero. Point \( M(1,0,0) \), where \( \mu_{\alpha } (x) \) equals 1, represents the ideal-positive element. For our example \( \alpha (600) \) is such an ideal point, because the corresponding annual profit level satisfies the manager to the fullest. Point \( N(0,1,0) \) where \( \nu_{\alpha } (x) \) equals 1, is called ideal-negative element. It is insofar “ideal” because one can argue (on the base of our example), that for the manager perfectly knowing what completely dissatisfies him is as good as perfectly knowing what satisfies him to the fullest. Point \( O(0,0,1) \), where \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) \) equals 1, expresses total ignorance concerning the positivity or negativity of the corresponding attribute referred to \( x \). In the case of our manager, e.g., selected achievable profit levels may be entailed with consequences that (s)he cannot at all assess in advance.

The line connecting point \( M \) and \( N \), with \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) = 0 \) and therefore \( \mu_{\alpha } (x) + \nu_{\alpha } (x) = 1 \), represents elements that are compatible with the traditional fuzzy set definition. In our example, point \( \alpha (100) = (0.2, 0.8, 0) \) would be such a point, because we also can find a full corresponding element in \( \tilde{A} \) from the traditional fuzzy example. Lines parallel to the line connecting point \( M \) and \( N \), capture elements with equal degrees of indeterminacy. In our example, elements \( \alpha (300) \), \( \alpha (400) \) and \( \alpha (500) \) have equal indeterminacy degrees (0.1). Graphically, they are therefore displayed on one parallel line. Generally, the closer a parallel line is to point \( O \), the higher is the degree of indeterminacy.

Finally, we want to present selected arithmetic operations on i-fuzzy values. Based on operations for i-fuzzy sets (Atanassov 1986; De et al. 2000) Xu (2007a) defines the following arithmetic operations for two given i-fuzzy values, \( \alpha (x) = (\mu_{\alpha } (x), \nu_{\alpha } (x)) \) and \( \alpha (y) = (\mu_{\alpha } (y), \nu_{\alpha } (y)) \):

For these definitions, Xu (2007a) uses the pair notation of i-fuzzy values. Here, the resulting indeterminacy degrees \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) \) are determined from the difference \( 1 - \mu_{\alpha } (x)^{'} - \nu_{\alpha } (x)' \), where \( \mu_{\alpha } (x)^{'} \) and \( \nu_{\alpha } (x)' \) are the results of the arithmetic operations.

As already discussed in previous work (Metzger and Spengler 2017), i-fuzzy sets and i-fuzzy values have similar mathematical definitions, but their applications can pursue different goals. On the one hand, i-fuzzy values are used to condense information related to an element \( x \). An example frequently presented in the literature is the group voting case. Imagine a group of 10 persons that are asked to vote on the implementation of a strategy. Three people vote for the implementation, five against and two abstain. The derived i-fuzzy value condensing these information would thus be α = (0.3, 0.5, 0.2) (see e.g., Szmidt 2014; Xu 2007b; Zhao et al. 2014). On the other hand, i-fuzzy values are often applied to model imprecision in multi-criteria decision problems. For that, e.g., one or several decision-makers are requested to (separately) assess predefined attributes of decision-relevant alternatives by use of i-fuzzy values. In this context \( \mu_{\alpha } (x) \) represents the degree of the positive and \( \nu_{\alpha } (x) \) the degree of negative assessment with respect to these attributes. Here, \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) \) can be an expression of either neutrality, undecidedness or unknowingness. To generate an overall evaluation of the respective alternative, all i-fuzzy values regarding the corresponding attributes are aggregated to a single i-fuzzy value. In this way, all decision-relevant information that is available concerning alternatives is summarized and condensed to an i-fuzzy value triple (see e.g., Atanassov et al. 2005; Xu and Yager 2008). Using different ranking methods (for overview, see Szmidt 2014), the corresponding alternatives can then be ranked and placed in a preference order. These examples show that possible applications offered by the construct of an i-fuzzy value go beyond the set-theoretic basic functions described in the beginning of this chapter. Overall, we can say that i-fuzzy theory provides powerful instruments to map uncertain knowledge acquired from incomplete information. Especially the construct of \( \pi_{\alpha } (x) \), which we can either interpret as undecidedness or as unknowingness will be the key element of our model presented in the next chapter.

4 An intuitionistic fuzzy approach for decision problems with ambiguous information

The starting point for our model is a decision matrix as presented in Table 1. We denote alternatives by \( a_{i} \left( {i = 1,2, \ldots ,n} \right) \) and states by \( s_{j} (j = 1,2 \ldots ,m) \) with corresponding probabilities \( p(s_{j} ) \). Consequences are denoted by \( c_{ij} \). In a business management context, for example \( a_{i} \) could represent investment alternatives, \( s_{j} \) various market development states and the \( c_{ij} \) cash flows, which are dependent on the respectively chosen alternative and the occurring market development state.

Within our approach, we assume that the decision-maker has sufficient information to specify point probability values for all states \( s_{j} \). Alternatively, we can assume that they are exogenously given. Other than that, (s)he is only able to present imprecise assessments on utility values for the respective consequences \( u(c_{ij} ) \). The sources for such imprecise utility assessments can be different: On the one hand, the consequences themselves may be vague and thus have ambiguous utilities for the decision-maker. On the other hand, the respective consequences may be precisely determinable, but the corresponding utilities are not clear to the decision-maker. These cases are relevant in particular, if the consequences are non-monetary. For reasons of simplicity, in the following we do not distinguish between these sources of utility ambiguity. Both can be processed equally within our approach. We rather want to focus on the formal expression and the handling of these imprecise utility assessments within ambiguous decision situations. For this, we use trivalent i-fuzzy values, which we substantially adapt for the underlying problem as follows: \( \alpha_{u} (c_{ij} ) = (\mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ),\nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ), \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} )) \). Table 2 shows the structure of imprecise utility assessments formally described by i-fuzzy values.

We interpret the single elements of \( \alpha_{u} (c_{ij} ) \) as follows: \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \) reflects the utility level, which is necessarily realized according to the decision-maker’s judgements. In other words, this degree corresponds to the lowest possible utility value that the decision-maker assigns to the corresponding consequence \( c_{ij} \). \( \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \) expresses the degree, to which \( c_{ij} \) relatively displeases him. We can also understand it as a degree of relative disutility of \( c_{ij} \). In addition, \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \) reflects the degree, to which the decision-maker is unsure about the utility assessment of \( c_{ij} \).

The following interdependencies apply: \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \in \left[ {0, 1} \right], \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \in \left[ {0, 1} \right] \) with \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) + \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \le 1 \) and \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) = 1 - \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) - \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) \). Thus, i-fuzzy values, where \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} \) equals 0 can be “translated” to point utility values. This is because in that case we presume that the decision-maker has sufficient information to precisely determine the utility and disutility degree of the corresponding consequence. I-fuzzy values with \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (c_{ij} ) > 0 \) indicate an incomplete information basis regarding utility assessment. This representation allows us to map decision-maker’s attitudes towards consequence values in a much more differentiated way, especially because it enables us to express formally his or her ignorance towards these variables.

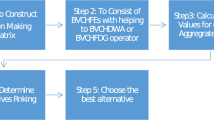

Within the next step, we aggregate the imprecise utility judgments expressed by i-fuzzy values. To do this, we first apply Formula (3) to weight the i-fuzzy utilities with the corresponding state probabilities, and then aggregate them for each alternative using Formula (1). The values thus obtained, reflect the decision-maker’s imprecise expected utility assessment for each alternative \( a_{i} \). Substantially they are also i-fuzzy values and are denoted by \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) = (\mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ), \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ),\pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} )) \). To derive meaningful interpretations of the single elements of \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) \) we define the two following sets that are interrelated with \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) \).Footnote 4 Let \( G_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} \) be a set of i-fuzzy values with \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) \) being the reference element.

This set \( G_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} = \left\{ {\alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) | \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) + \lambda_{1} \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ),\nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) + \lambda_{2} \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} )} \right\} \) with \( \lambda_{1} \in \left[ {0,1} \right] \), \( \lambda_{2} \in \left[ {0,1} \right] \) and \( \lambda_{1} + \lambda_{2} \le 1 \) describes all elements that can arise from possible (partial) redistributions of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \). Such redistributions apply in cases, where indeterminacy according to an evaluated element reduces to a certain degree.

Additionally, we define a subset \( H_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} \subseteq G_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} \) as \( H_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} = \left\{ {\alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) | \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) + \lambda \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ), \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) + \left( {1 - \lambda } \right)\pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} )} \right\} \) with \( \lambda \in [0,1] \) representing all possible total redistributions of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \). These are cases, where the indeterminacy referred to an evaluated element fully vanishes. We assume that formal redistributions of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) and therefore (partial or full) reductions of indeterminacy, resulting from improvements of the decision-maker’s information state. For illustration, let us exemplarily assume \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) \) being \( (0.3, 0.2, 0.5) \). Mapping this element into our MNO-triangle, we can see from Fig. 3, that set \( G_{{\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )}} \) is geometrically represented by the hatched triangle and from Fig. 4, that its subset \( H_{{\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )}} \) is expressed by the highlighted black line.

From Fig. 4 we can also see that all elements of \( H_{{\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )}} \) are bounded by two elements, which we denote by \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{min} \) and \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{max} \). For our example we get \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{min} = (0.3, 0.7, 0) \), which represents a full distribution of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) to \( \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) and \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{max} = (0.8, 0.2, 0) \), representing a full distribution of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) to \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \). As previously defined, i-fuzzy values with an indeterminacy degree of 0 can be interpreted as point utility values. Bringing all this together, we can sum up the following for the present case: an alternative \( a_{i} \), which overall expected utility has been evaluated by \( (0.3, 0.2, 0.5) \), is highly ambiguous and indicates a decision-maker having a relatively poor information state regarding this alternative. Improving this information state leads to a revision of the assessment, which formally results in a redistribution of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \). We assume that after the occurrence of state s the resulting consequence of the previously chosen alternative is observable. Treating this as equivalent to the instant improvement of information state, the corresponding utility value is thus also observable for the decision-maker. In this regard \( H_{{\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )}} \) represents the set of expected values, which anticipates all potential cases of the redistribution of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) and with it, all cases of realizable (point) expected utility values at the time of the decision.Footnote 5

From the ex ante perspective our example, \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) = (0.3, 0.2, 0.5) \), may take any expected utility values between \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{ \hbox{min} } = (0.3, 0.7, 0) \) (least favorable case) and \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{ \hbox{max} } = (0.8, 0.2, 0) \) (most favorable case). Translating these into point values, we would say that the actual expected utility value of \( a_{i} \) is located between \( 0.3 \) and \( 0.8 \). Hence, the decision-maker has a vague decision basis. In order to choose that alternative, which maximizes his or her overall expected utility, (s)he needs further decision support. In the following, we introduce two types of suitable approaches for the choice of alternatives in those situations.

First, we propose to make use of intuitionistic ranking functions, being the most common method for ranking i-fuzzy alternatives. The core elements of such ranking functions are similarity or distance measures. A broad overview and mathematical foundations of these concepts are presented by Szmidt (2014). For our purposes, we exemplarily apply the ranking method as suggested by Szmidt and Kacprzyk (2010). Within this approach, it is assumed that an alternative evaluated with \( (1,0,0) \) represents the ideal-positive alternative (referring to our MNO-diagram this point is denoted by M). Possible interpretations are, e.g., the alternative is fully satisfying the decision-maker regarding his or her objectives or, per se, is leading to the maximum (expected) utility for the decision maker. The corresponding ranking values, which we denote by \( R(\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )) \), are based on a normalized Hamming distance (Hamming 1950) between \( M(1,0,0) \) and the respective i-fuzzy alternative \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} ) \). We determine them as follows:

The lower the value \( R(\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )) \), the better is the respective alternative \( a_{i} \) in terms of the extent and reliability of (positive) information concerning its expected utility. To determine the relatively best alternative for the present decision situation, we propose to account \( R(\alpha (a_{i} )) \) as preference value and apply the following objective function:

As alternative approach, we propose to combine the results obtained by the i-fuzzy method with adapted decision criteria as applied in maxmin expected utility model (Gilboa and Schmeidler 1989) and \( \alpha \)-maxmin expected utility model (Ghirardato et al. 2004). First, we want to focus on the maxmin approach. Having a set of possible expected utility values, it suggests choosing the alternative with the highest minimum expected utility value. It is considered as pessimistic approach, because the decision-maker rather prefers to “play safe”, neglecting possibilities to achieve higher utility values. For our i-fuzzy alternatives we elaborated \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{ \hbox{min} } \) being the element representing the least favorable case and with it expressing the lowest achievable utility value. This represents the situation, where \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) totally redistributes to \( \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \). Therefore, \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) is accounted as the only element that is relevant for the final assessment of \( a_{i} \) and thus for the decision. On that basis, we suggest to apply the following objective function in order to determine the relatively best alternative for the corresponding decision situation:

Unlike a pessimist, an optimistic decision-maker rather focuses on the most favorable cases regarding the development of variables. Within our i-fuzzy approach, we stated that \( \alpha_{u} (a_{i} )_{ \hbox{max} } \) are elements representing the most favorable cases, and therefore the highest achievable utility values. Formally, it expresses a total redistribution of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) to \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \). Therefore, the sum of \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} \left( {a_{i} } \right) \) and \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} \left( {a_{i} } \right) \) is accounted as preference value and the following objective function is appliedFootnote 6:

Integrating the core ideas of the \( \alpha \)-maxmin expected utility model by Ghirardato et al. (2004) as explained in Sect. 1, we can further determine the overall expected utility as the weighted average of maximum and minimum expected utility for each alternative. In terms of our approach we therefore need to refer to our previously defined set \( H_{{\alpha_{u} (a_{i} )}} \), which represents all achievable combinations of the most and least favorable utility results. Formally, it expresses all possible redistribution of \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) to \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) and \( \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \).

Contrasting the interpretation of Ghirardato et al. (2004), for our approach, we do not interpret the weights as decision-maker’s ambiguity attitudes. For our approach, we regard it as more suitable to stick to the original interpretation for the weights as expressions of optimism and pessimism considerations, as suggested by Hurwicz (1951). Hence, the higher the value of \( \lambda \), the more the decision-maker believes in achieving a favorable result. Therefore, the sum of \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) and \( \lambda \)-weighted \( \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \) is accounted as preference value and the following objective function is applied:

Which of the presented decision criteria a decision-maker should choose for the solution of the formulated problem, depends on his or her ambiguity attitude. For example, a decision-maker who has a strong aversion towards ambiguity and perceives ambiguity as threat would rather choose the i-fuzzy-maxmin criterion. A decision-maker who has a strongly positive perception of ambiguity would rather apply the i-fuzzy-maxmax criterion. The i-fuzzy-Hurwicz criterion is applicable for the formal expression of combinations of extreme attitudes towards ambiguity.

In the following, we present a numerical example to illustrate our i-fuzzy approach and the application of the above elaborated decision criteria. For reasons of simplification we consider four alternatives \( a_{i} \left( {i = 1,2,3,4} \right) \) and two states \( s_{j} (j = 1,2) \). Table 3 presents the corresponding problem structure, where utility values of the underlying consequences have already been assessed by the decision-maker using i-fuzzy values.

Weighting the single i-fuzzy utility values with the given probabilities according to Formula (3), we get weighted i-fuzzy utility values (rounded to two decimal places) as presented in Table 4.

Aggregating the weighted i-fuzzy utility values for each alternative according to Formula (1), we get the following i-fuzzy expected utility values (rounded to two decimal places) for alternatives \( a_{1} - a_{4} \):

Using MNO-representation (Fig. 5), we can illustrate how the i-fuzzy values for alternatives \( a_{1} - a_{4} \) are geometrically distributed. Regarding these as reference elements as shown in Fig. 5, we can derive that the actual expected utility of \( a_{1} \) is in between 0.67 and 0.84, of \( a_{2} \) in between 0 and 0.77, of \( a_{3} \) in between 0.47 and 1 and of \( a_{4} \) is in between 0.44 and 0.66.

Finally, Table 5 presents the results we get from the application of the proposed decision criteria to the i-fuzzy expected values from the example. The bold emphasized preference values indicate which alternative is the best and hence chosen by the decision-maker, when applying the corresponding criterion. Figures 6 illustrate the geometrical solutions of the latter four results from Table 5.

The presented model is not limited to the formulation and solving of decision problems where (solely) the utility values are ambiguous. Analogously, we can use its basic concept to formalize and solve problems, where, e.g., probability assessments or both, utility and probability assessments are imprecise. The latter case has been examined in detail by Metzger and Spengler (2017). This work also presents a comprehensive discussion on interdependencies between selected fuzzy measures and i-fuzzy values, used as substitutes for probability measures.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a model for the formulation and solving of decision problems under ambiguity. Therefore, we generalize the definition of ambiguous situations, which we understand as cases, in which the decision-maker has imprecise (uncertain or vague) knowledge that results from incomplete information and can affect all elements of the decision field and the objective function. Adopting decision criteria from maxmin expected utility model (Gilboa and Schmeidler 1989) and \( \alpha \)-maxmin expected utility model (Ghirardato et al. 2004), we develop a decision model that combines elements of established approaches for the formal handling of uncertainty with instruments of intuitionistic fuzzy theory. In particular, we use intuitionistic fuzzy values as expression of decision-maker’s imprecise assessments on utility values and provide selected approaches for the solution of corresponding decision problems. The appropriateness of the applied criterion depends on the ambiguity attitude of the respective decision-maker.

In this paper, we focus on the formulation and solving of decision problems where (solely) the utility values are ambiguous. Analogously we can use its basic concept to formalize and solve problems, where, e.g., probability assessments or both, utility and probability assessments are imprecise. In order to elicit imprecise utility assessments of decision-makers, it is possible to apply an adapted version of the classical Bernoulli game [based on Ramsey’s (1926) work]. Imprecise probability values can be derived, e.g., from interval-valued probability judgements (see e.g., Metzger and Spengler 2017). Respective applications in intuitionistic fuzzy contexts can be addressed in further research projects.

The presented approach provides great potential to undertake extensive decision-supporting contribution in different (especially economic) areas. Similarly, the intuitionistic fuzzy approach offers a basis for modeling behavioral violations of rationality axioms of (subjective) expected utility theory. On this basis, we suggest to assess the predictive quality of the model by means of subsequent experimental investigations. In particular, subsequent experiments could aim an investigation of how the decision criteria choice of a “real” decision-maker is affected by his or her ambiguity attitudes.

Before that, however, it is important to further examine the model concept, which is still at an early stage of development. For example, other possible decision criteria should be considered and reviewed in terms of their impact on outcomes. In addition, it is important to examine to what extent classical and adapted axioms of rational behavior are (not) compatible with the approach presented.

Notes

For translated version, see Bernoulli (1954).

For the purposes of our approach, we will later on not refer to this interpretation of decision weights.

For reprinted version, see Brouwer (1999).

We derive these sets from two operators (\( D_{\alpha } \) and \( F_{\alpha ,\beta } \)) for i-fuzzy sets as suggested by Atanassov (1999).

There are also cases possible, in which after occurrence of state s the respective consequence of the previously chosen alternative \( a_{i} \) is observable to the decision-maker. But yet, he or she is still not able to fully determine a precise utility value. Therefore, we would have to consider all elements of set \( G_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} \) instead of its subset \( H_{{\alpha_{u} \left( {a_{i} } \right)}} \). For reasons of simplification, we do not examine such cases in this paper.

Because it applies that \( \mu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) + \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) + \pi_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) = 1 \), we equivalently can use the following objective function: \( \nu_{{\alpha_{u} }} (a_{i} ) \to \mathop {\hbox{min} }\limits_{i} ! \).

References

Al-Najjar, Nabil, and Jonathan Weinstein. 2009. The ambiguity aversion literature: A critical assessment. Economic and Philosophy 25 (3): 249–284.

Atanassov, Krassimir T. 1986. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 20 (1): 87–96.

Atanassov, Krassimir T. 1999. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets—Theory and Applications. Heidelberg: Physica.

Atanassov, Krassimir T. 2005. Answer to D. Dubois, S. Gottwald, P. Hajek, J. Kacprzyk and H. Prade’s paper “Terminological difficulties in fuzzy set Theory—The case of “Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets””. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 156 (3): 496–499.

Atanassov, Krassimir T., Gabriela Pasi, and Ronald R. Yager. 2005. Intuitionistic fuzzy interpretations of multi-criteria multi-person and multi-measurement tool decision-making. International Journal of System Science 36 (14): 859–868.

Bernoulli, Daniel. 1954. Exposition of a New Theory on the Measurement of Risk. Econometrica 22 (1): 23–36.

Brouwer, Luizen E.J. 1999. Intuitionism and Formalism. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 37 (1): 55–64.

Budner, Stanley. 1962. Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. Journal of Personality 30 (1): 29–50.

Camerer, Colin, and Martin Weber. 1992. Recent Developments in Modeling Preferences: Uncertainty and Ambiguity. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 5 (4): 325–370.

Choquet, Gustav. 1954. Theory of Capacities. Annales de l’institut Fourier 5: 131–295.

Curley, Shawn P., J.Frank Yates, and Richard A. Abrams. 1986. Psychological Sources of Ambiguity Avoidance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 38 (2): 230–256.

Curley, Shawn P., and J.Frank Yates. 1989. An Empirical Evaluation of Descriptive Models of Ambiguity Reactions in Choice Situations. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 33 (4): 397–427.

De, Supriya K., Ranjit Biswas, and R.Roy Akhil. 2000. Some operations on intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 114 (3): 477–484.

Dorsch, Friedrich, Hartmut Haecker, and Kurt H. Stapf. 1994. Dorsch Psychologisches Wörterbuch. Bern: Hans Huber.

Dubois, Didier, and Henri Prade. 1980. Fuzzy sets and systems: theory and applications. San Diego: Academic Press.

Dubois, Didier, and Henri Prade. 1985. A review of fuzzy set aggregation connectives. Information Sciences 36 (1–2): 85–121.

Dubois, Didier, Siegfried Gottwald, Peter Hajek, Janusz Kacprzyk, and Henri Prade. 2005. Terminological difficulties in fuzzy set theory—The case of “Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets”. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 156 (3): 485–491.

Einhorn, Hillel J., and Robin M. Hogarth. 1986. Decision Making under Ambiguity. Journal of Business 59 (4): 225–250.

Ellsberg, Daniel. 1961. Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 75 (4): 643–669.

Fox, Craig.R., and Amos Tversky. 1995. Ambiguity Aversion and Comparative Ignorance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (3): 585–603.

Franke, Guenther. 1978. Expected Utility with Ambiguous Probabilities and ‘irrational’ Parameters. Theory and Decision 9 (3): 267–283.

Frisch, Deborah, and Jonathan Baron. 1988. Ambiguity and Rationality. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 1 (3): 149–157.

Furnham, Adrian, and Joseph Marks. 2013. Tolerance of ambiguity: A review of the recent literature. Psychology 4 (9): 717–728.

Furnham, Adrian, and Tracy Ribchester. 1995. Tolerance of ambiguity: A review of the concept, its measurement and applications. Current Psychology 14 (3): 179–199.

Ghirardato, Paolo, Fabio Maccheroni, and Massimo Marinacci. 2004. Differentiating ambiguity and ambiguity attitude. Journal of Economic Theory 118 (2): 133–173.

Gilboa, Itzhak, and Massimo Marinacci. 2016. Ambiguity and the Bayesian Paradigm. In Readings in Formal Epistemology, ed. Horacio Arló-Costa, Vincent Hendricks, and Johan van Benthem, 385–439. Cham: Springer International.

Gilboa, Itzhak, and David Schmeidler. 1989. Maxmin expected utility with a non-unique prior. Journal of Mathematical Economics 18 (2): 141–153.

Gottwald, Siegfried. 2006. Many-Valued Logics. In Philosophy of logic, ed. Dale Jacquette, 675–722. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Hamming, Richard W. 1950. Error detecting and error correcting codes. Bell System Technical Journal 29 (2): 147–160.

Hurwicz, Leonid. 1951. Optimality criteria for decision making under ignorance, 370. Cowles Commission Discussion Paper: Statistics, No.

Kahn, Barbara E., and Rakesh K. Sarin. 1988. Modeling Ambiguity in Decisions Under Uncertainty. Journal of Consumer Research 15 (2): 265–272.

Kunreuther, Howard, Jacqueline Meszaros, Robin M. Hogarth, and Mark Spranca. 1995. Ambiguity and underwriter decision processes. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 26 (3): 337–352.

Lauriola, Marco, Renato Foschi, Oriana Mosca, and Joshua Weller. 2016. Attitude toward ambiguity: Empirically robust factors in self-report personality scales. Assessment 23 (3): 353–373.

McLain, David L. 1993. The MSTAT-I: A new measure of an individual’s tolerance for ambiguity. Educational and Psychological Measurement 53 (1): 183–189.

McLain, David L., Efstathios Kefallonitis, and Kimberly Armani. 2015. Ambiguity tolerance in organizations: definitional clarification and perspectives on future research. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 344.

Metzger, Olga, and Thomas Spengler. 2017. Subjektiver Erwartungsnutzen und intuitionistische Fuzzy Werte. In Entscheidungsunterstuetzung in Theorie und Praxis, ed. Thomas Spengler, Wolf Fichtner, Martin J. Geiger, Heinrich Rommelfanger, and Olga Metzger, 109–137. Berlin: Springer.

Von Neumann, John, and Oskar Morgenstern. 1947. Theory of games and economic behavior, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ramsey, Frank P. 1926. Truth and Probability. In The Foundations of Mathematics and Other Logical Essays (1960), ed. Richard B. Braithwaite, 156–198. Paterson: Littlefield, Adams and Co.

Ries, Horst. 1994. Ambiguität. In Dorsch Psychologisches Wörterbuch, vol. 27, ed. Friedrich Dorsch, Hartmut Haecker, and Kurt H. Stapf. Bern: Hans Huber.

Savage, Leonard J. 1954. The Foundations of Statistics. New York: Wiley.

Schmeidler, David. 1989. Subjective probability and expected utility without additivity. Econometrica 57 (3): 571–587.

Slovic, Paul, and Amos Tversky. 1974. Who accepts Savage’s axiom? Behavioral Science 19 (6): 368–373.

Spengler, Thomas. 2015. Ambiguitätssensitivität im Szenariomanagement. In Entscheidungstheorie und –praxis, ed. Heike Y. Schenk-Mathes and Christian Köster, 55–70. Berlin: Springer.

Szmidt, Eulalia. 2014. Distances and Similarities in Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets. Berlin: Springer.

Szmidt, Eulalia, and Janus Kacprzyk. 2010. On an Enhanced Method for a More Meaningful Ranking on Intuitionistic Fuzzy Alternatives. In Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing, Part I, ed. Leszek Rutkowski, Rafal Scherer, Ryszard Tadeusiewicz, Lofti A. Zadeh, and Jacek M. Zurada, 232–239. Berlin: Springer.

Takeuti, G., and Satoko Titani. 1984. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Logic and Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set Theory. Journal of Symbolic Logic 49 (3): 851–866.

Wald, Abraham. 1949. Statistical decision functions. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 20 (2): 165–205.

Xu, Zeshui. 2007a. Intuitionistic preference relations and their application in group decision making. Information Sciences 177 (11): 2363–2379.

Xu, Zeshui. 2007b. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Aggregation Operations. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 15 (6): 1179–1187.

Xu, Zeshui, and Ronald R. Yager. 2008. Dynamic intuitionistic fuzzy multi-attribute decision making. International Journal of Approximate Reasoning 48 (1): 246–262.

Xu, Zeshui, and Ronald R. Yager. 2009. Intuitionistic and interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy preference relations and their measures of similarity for the evaluation of agreement within a group. Fuzzy Optimization and Decision Making 8 (2): 123–139.

Zadeh, Lotfi A. 1965. Fuzzy Sets. Information and Control 8 (3): 338–353.

Zadeh, Lotfi A. 1978. Fuzzy sets as a basis for a theory of possibility. Fuzzy Sets and Systems 1 (1): 3–28.

Zhao, Hua, Xu Zeshui, and Zeqing Yao. 2014. Intuitionistic fuzzy density-based aggregation operators and their applications to group decision making with intuitionistic preference relations. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzzyness and Knowledge-based Systems 22 (1): 145–169.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Metzger, O., Spengler, T. Modeling rational decisions in ambiguous situations: a multi-valued logic approach. Bus Res 12, 271–290 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-019-0087-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-019-0087-5