Opinion statement

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability in the USA. Numerous clinical practice guidelines specify non-pharmacological strategies as the core management approach for OA. Although several of these strategies are efficacious, clinical practice remains primarily focused on analgesic use and invasive treatments such as joint replacements. This practice gap may be due to several factors such as a lack of accessibility or awareness of non-pharmacological interventions in clinical care, concentration on pain alone—which neglects other disability-related symptoms such as fatigue, and sleep difficulty, and placement of prevention and wellness with this lifelong disease as lower priority on the part of providers and payers. As referral patterns to rehabilitation for OA are scant, future research should focus on how to package established non-pharmacological interventions and increase accessibility at the point of care when patients are seeking services. Providers then would have the means to link patients to the plethora of community resources for OA management. Furthermore, a more holistic approach to symptom management that targets physical activity, diet, education, and behavior change is needed, with interdisciplinary healthcare professionals playing a larger role in tailoring non-pharmacologic interventions to individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, affecting approximately 27 million adults in the USA [1]. It is a disease of the joint and joint structures that has no cure and most often affects the hands, knees, and hips. People with OA often experience joint-specific pain and functional limitations. However, OA pain is not necessarily limited to the joint. An emerging heterogeneous phenotype of OA includes joint pathology, psychological distress, and neurological processing of pain [2–4]. Within this complex pain model, centralized pain has been associated with additional health-related issues such as insomnia, depression, and fatigue [4–6].

Typical treatments for OA are focused on reduction or elimination of joint pain through medications or total joint replacement surgery. Unfortunately, these treatment options are most likely to occur in advanced stages of the disease and may not adequately serve the needs of many people with OA who can live for years, or even decades, with this chronic condition. As evidenced by the new phenotype of OA that is inclusive of psychological distress, the effects of OA often extend well beyond the joint. Patients may experience disability in their usual daily activities, reduced participation in valued activities, and diminished social roles (e.g., reduced capacity to work, volunteer, or caregiving) [7, 8]. Disability in OA may also vary depending on which joint or joints are affected (knee or hip OA). The risk of disability due to knee OA in particular is greater than that of any other chronic condition [9]. As OA increases in prevalence with age, comorbidities also have an effect on overall pain and disability. Specifically, OA is highly comorbid with obesity and type II diabetes [10–12]. Considering the inherent risks associated with pharmacological management of multiple comorbidities and surgical intervention for management of OA, it then follows that clinical practice guidelines recommend utilization of non-pharmacological approaches as fundamental to the treatment of OA [13, 14].

Integrating non-pharmacological interventions into OA care supports the key areas of exercise and physical activity, weight management and healthy nutrition, rehabilitation, and self-management education. The following article will focus on ideal practice and the state of the science in OA management using non-pharmacological approaches.

Non-pharmacological treatment options

Exercise

Exercise is one of the most extensively researched non-pharmacological interventions in OA. Among people with knee OA, there is strong evidence that any type of exercise has small to moderate positive effects on pain and physical function [15, 16] and small effects on quality of life [15]. These effects equated to absolute improvement of 12 % for pain, 10 % for physical function, and 4 % for quality of life for people in exercise groups compared to those who were not in exercise groups [15]. Further, these effects have been sustained between two and six months post-cessation of the intervention. No differences have been found for the types of exercise (e.g., aerobic vs. resistive) [17]. A recent meta-analysis of exercise dose and type for knee OA showed that although all types of exercise were effective at reducing pain and improving reported physical function, stronger effects were shown when one type of exercise was the focus, when the program was supervised, and for programs that involved three sessions per week [18]. Fewer clinical trials are available evaluating the effectiveness of exercise in hip OA. In two recent meta-analyses, one examined effectiveness of land-based exercise, aquatic exercise, and manual physical therapy involving 19 studies [19] and the other examined effectiveness of land-based exercises involving ten studies [20]. Both meta-analyses concluded that exercise had at least small effects on pain in the short-term compared to a control condition [19]; although one meta-analysis concluded that pain and physical function only improved slightly among people with hip OA (8 and 7 % improvement, respectively) [20]. Like exercise, weight loss and dietary interventions have also been shown to reduce pain and improve function.

Weight loss/diet interventions

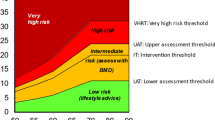

A large prospective study [21] found that BMI, weight, waist-hip ratio, and percent body fat was associated with increased incidence of both knee and hip OA. Accordingly, weight loss is recommended for people with lower extremity OA who are overweight [22, 23]. Most studies have included people with knee OA only [24], and in high quality studies, the effects on pain and physical function were small [25, 26]. Nevertheless, the combination of weight loss plus exercise has led to the greatest improvements in symptoms and function [26, 27]. Messier and colleagues [28••] examined the effects of an 18- month intervention of intensive weight loss (with a goal to lose 10 % of body weight), aerobic exercise, or a combination of the two on pain, physical function, inflammation (IL-6), and knee compressive forces. The combination of diet plus exercise led to greater weight loss (11 % of body weight compared to 10 % in the diet alone group and 2 % in the exercise alone group). The combined group also showed the largest improvements in pain and function compared to the other groups. Additionally, knee compressive forces improved in all three groups. More weight lost, regardless of group assignment at baseline, was associated with better knee compressive force, lower IL-6, decreased pain, and improved function at 18 months.

Unsurprisingly, animal models have linked high-fat diets in particular to increased obesity, increased IL-6, Type II diabetes, and accelerated progression of OA [29–31]. Although biomechanical factors such as elevated BMI have been noted to play a role in knee and hand OA, some studies suggest that metabolic dysfunction in particular, as evidenced by elevated HgA1c levels, may play an even greater role in accelerated OA progression compared to weight alone [32–34]. Therefore, specific dietary recommendations should focus on reducing intake of foods with a high glycemic index [35] (potatoes, rice, sugar, processed foods, and foods with high trans-fat) and increasing intake of proteins, fruits, vegetables, monounsaturated fats (such as olive oil), and polyunsaturated fats (like flaxseed oil). Olive oil especially has demonstrated some evidence of reducing cartilage degeneration when combined with exercise [36].

Weight loss and dietary interventions for OA can be challenging for individuals to implement as food choices are often reflective of culture, income, and habit. Providers should advise all overweight patients on weight loss and dietary modifications, suggesting some daily physical activity and setting small weight loss goals such as an initial loss of 10 % of total goal at a safe rate. In addition to weight loss and dietary interventions, some individuals may require a more hands-on approach for OA management as offered through rehabilitation programs.

Rehabilitation interventions (physical and occupational therapy)

Manual therapy

Manual therapy is used in rehabilitation and may also be provided by chiropractors or other practitioners. This therapy involves mobilization of affected joints, muscle massage, and stretching. Although this is a recommended intervention from clinical practice guidelines [37, 38]; there is limited evidence to support its effectiveness. Problems with synthesizing the evidence base include the heterogeneity in trials which differ not only in terms of practitioners, but also in terms of dose and type of manual intervention (such as Swedish body massage, knee manipulation, or specific therapeutic approach), comparison group, and type of OA (knee or hip) [39]. Although trials may make a joint-specific distinction of including people with knee or hip OA, another potential confounder in examining effectiveness in trials is the extent of OA, as people may have multiple joints involved that include both the hip and knee. Compared to knee OA, recently, more high-quality trials have investigated hip OA and evidence is conflicting.

Two recent trials have evaluated manual therapy provided by physical therapists. Abbott and colleagues [40] investigated the use of manual therapy alone, exercise alone, or the combination of manual therapy and exercise in comparison to a usual care group of participants with knee or hip OA. They found that both exercise and manual-therapy-alone groups showed significant improvements in total WOMAC score at 9 weeks and 1 year, and the combination group did not show additional benefit [40]. In contrast, a trial by Bennell and colleagues [41••] compared manual therapy plus other physical therapy strategies (home exercise, education, and assistive device prescription) to a sham therapy which included the use of ultrasound and application of an inert gel to the affected joint. In this highly controlled trial, both the treatment and sham groups experienced significant benefits in reported pain and physical function following treatment, and there were no significant differences between groups in objective physical measures. This finding calls into question the effectiveness of these techniques in hip OA and demonstrates the need for more highly rigorous trials in this area.

Bracing

A common form of bracing in knee OA is the use of a valgus brace which is designed to offset joint load in people who have OA in the medial compartment of the tibiofemoral joint and is recommended in clinical practice guidelines [42]. A recent meta-analysis of six trials concluded that valgus bracing had small to moderate effects on pain and function, and the effect depended on study design. Optimal practices for bracing are not known as instructions on wearing the brace varied widely in these studies and there were differences in type of brace (off the shelf versus custom fit) used [43]. Lateral wedge insoles are another treatment used to treat medial knee OA. A recent meta-analysis of 12 trials showed no statistically or clinically important improvement in pain in higher quality studies and using a control condition of a neutral insole [44]. The findings do not support the use of lateral insoles as a treatment for medial knee OA.

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) has been a recommended treatment for pain relief in OA in many clinical practice guidelines [14, 37]. This involves applying electrodes to the skin using a small battery-operated unit that provides low-voltage electrical stimulation to the painful area. A meta-analysis of 18 trials in 2009 was inconclusive in its evidence to support TENS. The trials included in the analysis were small and of variable quality. Similar, modest improvements in pain were found across all treatment groups, those receiving TENS, a sham condition, or usual care [45]. A large clinical trial involving 224 participants was conducted in 2014 to determine the added effects of TENS for knee OA in combination with standard rehabilitation treatment which involved group education and exercise program. Participants were randomized into three arms: TENS + standard treatment, sham TENS + standard treatment, or standard treatment alone. In all groups, pain and physical function on the WOMAC improved after 6 weeks of intervention and was maintained for 24 weeks. Across the groups, 33–42 % reached clinically important improvements on physical function on the WOMAC (the primary outcome measure) and the active TENS + standard treatment group had the lowest percentage of people who reported this difference [46]. Thus, the current evidence does not support the use of TENS as a treatment in knee OA.

Assistive devices/technology

Assistive devices such as walking aids are widely recommended by many clinical practice guidelines to offset joint load in OA. In addition, other assistive devices that may reduce stress on joints may also be prescribed. There is not a strong evidence base to support these practices, although device prescription is common in clinical care. Some of these practices may be subsumed under a description of education in OA studies, but trials would be required to better understand how these devices are used and their effects.

Activity pacing

Activity pacing is the practice of regulating daily life activities or routines to meet goals [47]. This is a behavioral technique that is often taught in rehabilitation and also can be taught by psychologists. Activity pacing has been a source of conceptual confusion. In a survey of health professionals, 81 % said they teach pacing to patients, but there was not a consensus about what it entails [48]. One common form of activity pacing is called time-based activity pacing in which people are taught to adhere to a time schedule of activity and rest in order to not overdo activity which can lead to symptom flares, or to avoid long periods of rest which may also lead to symptom flares. Recently, a trial was conducted to examine time-based activity pacing delivered by occupational therapists for people with knee or hip OA. Participants were randomized into two conditions of time-based activity pacing (tailored based on physical activity and symptom patterns collected by an enhanced physical activity monitor), general activity pacing (similar instruction without the tailored feedback), and usual care. No significant group differences were found in pain or physical function; although lack of findings may be due to the brevity of the intervention (three sessions) or the low level of symptoms in the sample [49].

Physical rehabilitation interventions for OA can vary significantly. Though some patients may experience diminished pain and improved function from therapies, recent studies evidence overall effects to be minimal at best. As the OA phenotype is also inclusive of psychological components, cognitive behavioral treatment approaches rooted in psychology may appropriately address these concerns.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of psychotherapy whereby negative patterns of thinking, behavior, and emotional responses are challenged and restructured, thereby facilitating behavior change [50]. CBT has been incorporated into interventions that address pain and sleep disturbances, two common symptoms of OA that adversely impact function and mental and emotional well-being [51, 52•].

Cognitive behavioral therapy for pain (CBT-P)

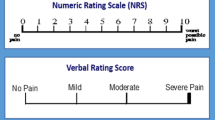

CBT that targets pain (CBT-P) may include strategies ranging from problem solving and pain coping skills training (PCST), to goal-setting and relaxation [53]. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing CBT-P to general practice primary care showed no differences between the two groups with regards to pain or function [54]. Additionally, a negative impact of the CBT-P intervention on pain self-efficacy was noted, possibly due to the participants becoming more conscious of their pain and behaviors and how pain has been impacting their lives.

In some instances, a single therapeutic strategy from CBT-P, most often PCST, has been integrated into OA management interventions, resulting in small to medium treatment effects. For example, a nurse practitioner-led program found that PCST reduced pain intensity and interference while improving pain coping and self-efficacy for controlling pain; only small effects were observed [55]. In a RCT of an automated, internet-delivered PCST program, medium effects were documented, with the intervention group showing significant improvements in pain and self-efficacy compared to an assessment-only control group [56]. Current evidence for CBT-P and use of individual strategies such as PCST is equivocal at best and likely to result in small to medium treatment effects.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT has also been used to treat insomnia (CBT-I) and may involve strategies such as sleep restriction, sleep hygiene education, stimulus control, or cognitive therapy for insomnia [57]. A study by Smith et al. [51] showed that CBT-I significantly improved objective and subjective sleep and insomnia compared to a behavioral desensitization placebo. These improvements were comparable to the meta-analytic, post-treatment effects of benzodiazepine receptor agonist sedative hypnotic [58]. Overall, CBT-I appears to improve sleep-related issues in OA.

CBT-P combined with CBT-I (CBT-PI)

A combination of CBT-P and CBT-I (referred to as CBT-PI) has been investigated. A large-scale RCT compared CBT-PI to CBT-P and included an education control group that was provided non-directive pain and sleep education [59]. Severity of insomnia and pain decreased and arthritis scores (including pain and function) improved in all groups. Adding the insomnia component to the CBT-P improved insomnia ratings compared to CBT-P and education only. CBT-P did not improve pain ratings, however, but did have indirect positive effects on sleep efficiency [52]. In a secondary analysis, regardless of group, those who showed improvements in insomnia symptoms at 2 months reported long-term, sustained sleep quality benefits at an 18-month follow-up [60]. These improvements in sleep were associated with long-term improvements in pain severity, arthritis symptoms, and fatigue. Current evidence for use of CBT-PI shows promise in addressing symptoms of pain and insomnia simultaneously.

Community-based and self-management programs

Community-based and self-management programs for arthritis shift the primary responsibility of wellness maintenance and disease management from the healthcare system to the community and to individuals with OA. A systematic review that primarily included community-delivered OA exercise programs showed that individuals who participate in such programs show more favorable outcomes related to function and health-related quality of life compared to those who only receive standard of care (i.e., attend scheduled consultation visits with a healthcare professional) [61]. Adverse outcomes have rarely been reported, aside from potential mild musculoskeletal discomfort resulting from increased exercise, suggesting that these programs are a safe non-pharmacological option for self-management of OA.

There are a number of arthritis-specific community and self-management programs available for individuals with OA (Table 1). They vary widely in terms of duration, intensity, cost, key components, instructor qualifications, targeted arthritis issues, and evidence supporting their effectiveness in improving health outcomes. For instance, the Arthritis Self-management Program (ASMP), typically taught by peers with arthritis, is a self-help education program for persons with arthritis and has been shown to significantly improve self-efficacy, health behaviors (e.g., communication with physicians), fatigue, anxiety, and depression [67]. The ASMP has multiple delivery formats ranging from in-person group sessions to a self-study toolkit. In contrast, a lesser researched program, the Arthritis Foundation Aquatic Program (AFAP), includes aquatic exercise offered by trainers at a recreational facility (e.g., YMCA), and focuses on endurance, joint range of motion, and aerobics. Participants have shown improvements in functional fitness, strength, flexibility, and quality of life [62–64]. Providing patients with a gamut of community-based program options will help to ensure that a patient can find the most suitable, sustainable program given his or her unique lifestyle and needs.

Emerging treatments and approaches

Combined patient/provider intervention

One recent OA clinical trial (n = 300) combined a telephone-based OA intervention for patients who received their care within the Veteran Affairs healthcare system with an intervention designed to assist primary care providers to tailor evidence-based treatments using clinical practice guidelines [78]. The telephone-based intervention was delivered by a trained health educator over a 12-month period and focused on weight management, physical activity, and pain coping skills training. The provider intervention was done by monitoring upcoming clinic visits and providing patient-specific recommendations in the electronic medical record to the primary care providers prior to the visit. The recommendations were provided based on an algorithm to help determine what treatment strategy may be reasonable for the primary care provider to consider and consisted of non-pharmacological options. Small improvements were found in the WOMAC, particularly in physical function (10 % improvement) at 12 months compared to a usual care group. Interestingly, while providers recommended more non-pharmacological interventions for participants in the intervention group compared to the control group, patients did not use them at a higher rate than usual care. The lack of utilization may be due to difficulty to access these treatments as they often require more frequent travel to the medical center. This intervention provides an innovative approach to help integrate evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments into clinical management for OA.

Investigation into CAM treatments

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to health practices developed outside of mainstream conventional medicine [79]. Non-pharmacological CAM therapies are extensive and inclusive of practices and treatments such as yoga, tai chi, qi gong, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, meditation, prayer, massage, acupressure, and acupuncture. Race and ethnicity appear to influence specific CAM therapy preferences. For instance, a large cross sectional study of over 9000 adults found increased use of acupuncture amongst Asians (15.8 %), increased use of prayer amongst Blacks (56.3 %), and increased use of massage amongst Whites (29.4 %) [80]. However, rather than race or ethnicity, the greatest predictors of CAM-use was presence of a chronic disease [80].

Within OA populations, CAM use is becoming increasingly prevalent, yet due to the highly individualized nature of many CAM treatment programs; large controlled studies are not typical. Interestingly, Shengelia and colleagues [81] completed a systemic review of studies testing the use of tai chi, yoga, acupuncture, and massage to manage OA and found these therapies to be effective in reducing pain and stiffness and improving physical functioning. However, when comparing CAM to exercise and conventional therapies, CAM typically underperforms [82]. For example, in evaluating the effectiveness of acupressure compared to isometric exercise and a control group, Sorour, Ayoub, and Abd El Aziz [83] found that although acupressure decreased pain the most, isometric exercise was the most effective at reducing stiffness and improving physical functioning amongst all treatment groups.

Despite the minimal treatment effects that CAM produces, Lapane and colleagues [82] observed in a study of more than 2000 patients with knee OA, that nearly 50 % of patients reported CAM use either solely or in conjunction with conventional medicine. Consequently, providers should query patients in-depth about use of CAM so as to avoid unintended negative interactions with additionally prescribed treatments, be prepared to respond to patient inquiries regarding CAM options, and recommend optimal therapies. Providers and patients may find CAM providers through the government website https://healthfinder.gov (type CAM into the search box).

Technology-based interventions

The use of technology-based interventions, particularly those that involve telehealth, or web or mobile device delivery, is increasing in popularity due to its versatility, cost-effectiveness, and potential to extend the reach of OA treatment beyond in-person contacts. Evidence supporting technology-based interventions, however, is still in its infancy compared to that which is available for more traditional delivery methods. Many published investigations of technology-based interventions are in the feasibility or efficacy testing phases. For instance, Clayton and colleagues [84] proposed a feasibility trial of a multifaceted intervention that includes a physical therapist-led educational module paired with use of a wrist-worn activity tracker and follow-up phone check-ins to increase physical activity engagement in persons with knee OA. Similarly, Bossen and team [85] are preparing an “E-Exercise” intervention comprised of visits with a physical therapist and an interactive website to improve exercise engagement in persons with lower extremity OA. Other innovative approaches under investigation include use of smartphone technology, such as an intervention prototype proposed by Ortiz et al.[86] that supplies customized TENS, electrical muscle stimulation, and iontophoresis therapy, activated by a smartphone application, and delivered through a Bluetooth-enabled knee orthosis. Although promising, substantially more evidence is required before the use of technology-based interventions for treatment of OA is empirically justified.

Conclusions

OA is a complex disease that requires interdisciplinary team support to manage pain, changes in function, and psychological correlates. Non-pharmacological treatments are the foundation of optimal OA disease management. Despite many effective interventions and strategies, non-pharmacological approaches are not well-integrated into clinical care. As the US population continues to age and experiences multiple chronic comorbidities including OA, providers need to be prepared to holistically manage OA by promoting patient self-care practices, recommending engagement in physical fitness and maintenance of healthy weight and nutrition. Furthermore, increased provider familiarity with available rehabilitative and integrative health services will likely lead to increased patient utilization and the creation of more opportunities to further evaluate efficacy of desired clinical outcomes.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Lawrence R, Felson D, Helmick C. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rehumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi:10.1002/art.23176.

Kittelson AJ, George SZ, Maluf KS, Stevens-Lapsley JE. Future directions in painful knee osteoarthritis: harnessing complexity in a heterogeneous population. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):422–32. doi:10.2522/ptj.20130256.

Sofat N, Ejindu V, Kiely P. What makes osteoarthritis painful? The evidence for local and central pain processing. Rheumatology. 2011. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker283.

Murphy SL, Lyden AK, Phillips K, Clauw DJ, Williams DA. The association between pain, radiographic severity, and centrally-mediated symptoms in women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(11):1543–9. doi:10.1002/acr.20583.

Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states—maybe it is all in their head. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):141–54. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2011.02.005.

Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in rheumatic diseases: future directions. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):291–302. doi:10.1002/art.37739.

McDonough CM, Jette AM. The contribution of osteoarthritis to functional limitations and disability. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):387–99. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2010.04.001.

Theis KA, Murphy L, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Sacks JJ. Arthritis restricts volunteer participation: prevalence and correlates of volunteer status among adults with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(7):907–16. doi:10.1002/acr.20141.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 7. Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999. MMWR. 2001;50:120–5.

New knee osteoarthritis study findings have been reported from lariboisiere hospital (diabetes is a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis progression). Obesity & Diabetes Week. 2015 2015/06/15/; p. 24.

Hawker GA. Osteoarthritis & obesity. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37 Suppl 2:S219.

Eymard F, Parsons C, Edwards MH, Petit-Dop F, Reginster JY, Bruyère O, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis progression. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(6):851–9. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2015.01.013.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):465–74. doi:10.1002/acr.21596.

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(2):137–62. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013.

Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424.

Fransen M, Marlene F, McConnell S. Land-based exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(6):1109–17. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090058.

Ettinger Jr WH, Burns R, Messier SP, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the fitness arthritis and seniors trial (fast). JAMA. 1997;277(1):25–31. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540250033028.

Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, Zhang W, Lund H. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66(3):622–36. doi:10.1002/art.38290.

Beumer L, Wong J, Warden SJ, Kemp JL, Foster P, Crossley KM. Effects of exercise and manual therapy on pain associated with hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095255.

Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2014(4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2.

Lohmander LS, Verdier MG, Rollof J, Nilsson PM, Engstro G. Incidence of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to different measures of body mass: a population-based prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):490–6. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.089748.

Bliddal H, Leeds AR, Christensen R. Osteoarthritis, obesity and weight loss: evidence, hypotheses and horizons—a scoping review. Obes Rev. 2014;15(7):578–86. doi:10.1111/obr.12173.

Zhang W. Risk factors of knee osteoarthritis—excellent evidence but little has been done. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(1):1–2. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2009.07.013.

Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):433–9. doi:10.1136/ard.2006.065904.

Christensen R, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Weight loss: the treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2005;13(1):20–7. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.008.

Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD, Morgan TM, Rejeski WJ, Sevick MA, et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the arthritis, diet, and activity promotion trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1501–10. doi:10.1002/art.20256.

Messier SP, Pater M, Beavers DP, Legault C, Loeser RF, Hunter DJ, et al. Influences of alignment and obesity on knee joint loading in osteoarthritic gait. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(7):912–7. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.05.013.

Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, DeVita P, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1263–73. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.277669. This rigorous trial involved 399 participants who underwent either an intensive weight loss intervention plus exercise, an intensive weight loss intervention alone, or exercise over 18 months. The combination of diet and exercise or diet alone had more weight loss and less inflammation (IL-6) than the exercise group. In addition, the diet group had greater reductions in knee compressive force compared to the other groups. This trial supports the importance of diet interventions in OA and an extra impact of combining diet and exercise.

Cortez M, Carmo LS, Rogero MM, Borelli P, Fock RA. A high-fat diet increases IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha production by increasing NF-kappaB and attenuating PPAR-gamma expression in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Inflammation. 2013;36(2):379–86. doi:10.1007/s10753-012-9557-z.

van der Kraan PM. Osteoarthritis and a high-fat diet: the full ‘OA syndrome’ in a small animal model. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(4):130. doi:10.1186/ar3082.

Brunner AM, Henn CM, Drewniak EI, Lesieur-Brooks A, Machan J, Crisco JJ, et al. High dietary fat and the development of osteoarthritis in a rabbit model. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2012;20(6):584–92. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.007.

Mooney RA, Sampson ER, Lerea J, Rosier RN, Zuscik MJ. High-fat diet accelerates progression of osteoarthritis after meniscal/ ligamentous injury. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011; 13(R198). doi:10.1186/ar3529.

O’Conor CJ, Griffin TM, Liedtke W, Guilak F. Increased susceptibility of Trpv4-deficient mice to obesity and obesity-induced osteoarthritis with very high-fat diet. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):300–4. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202272.

Kc R, Li X, Forsyth CB, Voigt RM, Summa KC, Vitaterna MH, et al. Osteoarthritis-like pathologic changes in the knee joint induced by environmental disruption of circadian rhythms is potentiated by a high-fat diet. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16896. doi:10.1038/srep16896.

Pereira EV, Costa JA, Alfenas RCG. Effect of glycemic index on obesity control. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2015;59:245–51.

Musumeci G, Trovato FM, Pichler K, Weinberg AM, Loreto C, Castrogiovanni P. Extra-virgin olive oil diet and mild physical activity prevent cartilage degeneration in an osteoarthritis model: an in vivo and in vitro study on lubricin expression. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:2064–75. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.07.007.

Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, Andeassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1125–35.

NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence). The care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG177;(accessed 6/17/2016).

French HP, Brennan A, White B, Cusack T. Manual therapy for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee—a systematic review. Man Ther. 2011;16(2):109–17. doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.10.011.

Abbott JH, Robertson MC, Chapple C, Pinto D, Wright AA, Leon de la Barra S, et al. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(4):525–34. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.12.014.

Bennell KL, Egerton T, Martin J, Abbott JH, Metcalf B, McManus F, et al. Effect of physical therapy on pain and function in patients with hip osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(19):1987–97. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4591. In this trial, 102 participants with hip OA underwent either 10 sessions of physical therapy or sham physical therapy. Outcomes were WOMAC pain and physical function and objective physical measures (walking, strenght, and balance). Both groups showed improvements in pain and function and little difference in effects on objective measures suggesting that this protocol of physical therapy was not effective to improve outcomes in hip OA. The use of sham treatment is uncommon in rehabilitation studies but is important in order to truly evaluate rehabilitation effectiveness.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(3):363–88. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003.

Moyer RF, Birmingham TB, Bryant DM, Giffin JR, Marriott KA, Leitch KM. Valgus bracing for knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(4):493–501. doi:10.1002/acr.22472.

Parkes MJ, Maricar N, Lunt M, LaValley MP, Jones RK, Segal NA, et al. Lateral wedge insoles as a conservative treatment for pain in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;310(7):722–30. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.243229.

Rutjes AW, Nuesch E, Sterchi R, Kalichman L, Hendriks E, Osiri M, et al. Transcutaneous electrostimulation for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;7(4):Cd002823. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002823.pub2.

Palmer S, Domaille M, Cramp F, Walsh N, Pollock J, Kirwan J, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation as an adjunct to education and exercise for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66(3):387–94. doi:10.1002/acr.22147.

Nielson WR, Jensen MP, Karsdorp PA, Vlaeyen JW. A content analysis of activity pacing in chronic pain: what are we measuring and why? Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):639–45. doi:10.1097/ajp.0000000000000024.

Beissner K, Henderson Jr CR, Papaleontiou M, Olkhovskaya Y, Wigglesworth J, Reid MC. Physical therapists’ use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for older adults with chronic pain: a nationwide survey. Phys Ther. 2009;89(5):456–69. doi:10.2522/ptj.20080163.

Murphy SL, Kratz AL, Kidwell K, Lyden AK, Geisser ME, Williams DA. Brief time-based activity pacing instruction as a singular behavioral intervention was not effective in participants with symptomatic osteoarthritis. Pain. 2016;157(7):1563–73. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000549.

Dobson KS. Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapies. New York: Guilford Publications; 2010.

Smith MT, Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Robinson M, Haque U, Quain A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, active placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67(5):1221–33. doi:10.1002/art.39048.

Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Keefe FJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: the lifestyles randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):947–56. doi:10.1111/jgs.12275. In this study, 367 individuals with osteoarthritis either received cognitive behavioral treatment for insomnia and pain or cognitive behavioral therapy for pain alone, or education. At 9 months, participants in cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and pain had the most improvement in insomnia severity, objective sleep quality, and pain compared to the other groups.

Carlson M. CBT for chronic pain and psychological well-being: a skills training manual integrating DBT, ACT, behavioral activation and motivational interviewing. Somerset: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014.

Helminen EE, Sinikallio SH, Valjakka AL, Vaisanen-Rouvali RH, Arokoski JP. Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioural group intervention for knee osteoarthritis pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(9):868–81. doi:10.1177/0269215514558567.

Broderick JE, Broderick JE, Keefe FJ, Schneider S, Junghaenel DU. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain is effective, but for whom? Pain (Amsterdam). 2016; 1. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000626.

Rini C, Porter LS, Somers TJ, McKee DC, DeVellis RF, Smith M, et al. Automated internet-based pain coping skills training to manage osteoarthritis pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2015;156(5):837–48. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000121.

Perlis M, Jungquist C, Smith M, Posner D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a session-by-session guide. New York: Springer; 2005.

Smith MT, Perlis ML, Park A, Smith MS, Pennington J, Giles DE, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatr. 2002;159(1):5–11.

Von Korff M, Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Balderson BH, Moore AL, Baker LD, et al. Group interventions for co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: the lifestyles cluster randomized trial design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(4):759–68. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.010.

Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Baker LD, Rybarczyk BD, Keefe FJ, et al. Short-term improvement in insomnia symptoms predicts long-term improvements in sleep, pain, and fatigue in older adults with comorbid osteoarthritis and insomnia. Pain. 2014;155(8):1547–54. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.032.

Desveaux L, Beauchamp M, Goldstein R, Brooks D. Community-based exercise programs as a strategy to optimize function in chronic disease: a systematic review. Med Care. 2014;52(3):216–26. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000065.

Patrick DL, Ramsey SD, Spencer AC, Kinne S, Belza B, Topolski TD. Economic evaluation of aquatic exercise for persons with osteoarthritis. Med Care. 2001;39(5):413–24.

Suomi R, Collier D. Effects of arthritis exercise programs on functional fitness and perceived activities of daily living measures in older adults with arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(11):1589–94.

Wang TJ, Belza B, Elaine Thompson F, Whitney JD, Bennett K. Effects of aquatic exercise on flexibility, strength and aerobic fitness in adults with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(2):141–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04102.x.

Callahan LF, Mielenz T, Freburger J, Shreffler J, Hootman J, Brady T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the people with arthritis can exercise program: symptoms, function, physical activity, and psychosocial outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(1):92–101. doi:10.1002/art.23239.

Minor M, Prost E, Nigh M, Ge B, Hewett J. Outcomes from the Arthritis Foundation exercise program: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:S309.

Brady TJ, Murphy L, Beauchesne D, Bhalakia A, Chervin D, Daniels B, et al. Sorting through the evidence for the arthritis self-management program and the chronic disease self-management program: executive summary of ASMP/CDSMP meta-analysis. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

Ackermann RT, Williams B, Nguyen HQ, Berke EM, Maciejewski ML, LoGerfo JP. Healthcare cost differences with participation in a community-based group physical activity benefit for medicare managed care health plan members. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1459–65. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01804.x.

Belza B, Snyder S, Thompson M, LoGerfo J. From research to practice: EnhanceFitness, an innovative community-based senior exercise program. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2010;26(4):299–309.

Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell R, Pollak N, Huber G, Sharma L. Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist. 2004;44(2):217–28.

Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell RT, Huber G, Pollak N, Sharma L, et al. Long-term impact of Fit and Strong! on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):801–14.

Seymour RB, Hughes SL, Campbell RT, Huber GM, Desai P. Comparison of two methods of conducting the Fit and Strong! program. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(7):876–84. doi:10.1002/art.24517.

Levy SS, Macera CA, Hootman JM, Coleman KJ, Lopez R, Nichols JF, et al. Evaluation of a multi-component group exercise program for adults with arthritis: fitness and exercise for people with arthritis (FEPA). Disabil Health J. 2012;5(4):305–11. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.07.003.

Bruno M, Cummins S, Gaudiano L, Stoos J, Blanpied P. Effectiveness of two arthritis foundation programs: walk with ease, and YOU can break the pain cycle. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(3):295–306.

Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M, Schoster B, Hootman J, Houenou LO, et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease Program. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(8):1098–107. doi:10.1002/acr.20490.

Wyatt B, Mingo CA, Waterman MB, White P, Cleveland RJ, Callahan LF. Impact of the Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease Program on arthritis symptoms in African Americans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E199. doi:10.5888/pcd11.140147.

Nyrop KA, Charnock BL, Martin KR, Lias J, Altpeter M, Callahan LF. Effect of a six-week walking program on work place activity limitations among adults with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(12):1773–6. doi:10.1002/acr.20604.

Allen KD, Yancy Jr WS, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Jeffreys AS, Datta SK, et al. A combined patient and provider intervention for management of osteoarthritis in veterans: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(2):73–83. doi:10.7326/M15-0378.

(NIH) NIoH. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? 2008. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health#cvsa; (Accessed June 15, 2016).

Hsiao A-F, Wong MD, Goldstein MS, Yu H-J, Andersen RM, Brown ER, et al. Variation in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use across racial/ethnic groups and the development of ethnic-specific measures of CAM use. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(3):281–90. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.281.

Shengelia R, Parker SJ, Ballin M, George T, Reid MC. Complementary therapies for osteoarthritis: are they effective? Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(4):e274–88. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2012.01.001.

Lapane KL, Sands MR, Yang S, McAlindon TE, Eaton CB. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with radiographic-confirmed knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2012;20(1):22–8. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2011.10.005.

Sorour AS, Ayoub AS, Abd El Aziz EM. Effectiveness of acupressure versus isometric exercise on pain, stiffness, and physical function in knee osteoarthritis female patients. J Adv Res. 2014;5(2):193–200. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2013.02.003.

Clayton C, Feehan L, Goldsmith CH, Miller WC, Grewal N, Ye J, et al. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a physical activity counseling intervention using Fitbit in people with knee osteoarthritis: the TRACK-OA study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2015;1:30.

Bossen D, Kloek C, Snippe HW, Dekker J, de Bakker D, Veenhof C. A blended intervention for patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis in the physical therapy practice: development and a pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(1):e32. doi:10.2196/resprot.5049.

Ortiz JM, Ruiz AT, Cuesta GS, editors. Design of a device for treatment of knee osteoarthritis with TENS, EMS and iontophoresis through an Android application on a smartphone. VI Latin American Congress on Biomedical Engineering CLAIB; 2014; Paraná, Argentina Springer International Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

SLM, SGRL, and SLSN declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

With regard to the authors’ research cited in this paper, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pain

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murphy, S.L., Robinson-Lane, S.G. & Niemiec, S.L.S. Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis Management: A Review of Current and Emerging Non-Pharmacological Approaches. Curr Treat Options in Rheum 2, 296–311 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-016-0054-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-016-0054-7