Abstractdata

Crossword puzzles have been utilised as a means of health professions education (HPE) gamification. A systematic review conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines was performed to evaluate the educational impact and describe the characteristics of crosswords in HPE contexts. Twenty-nine studies fulfilled inclusion criteria. Crossword puzzles are an enjoyable learning activity and provide positive educational impact. The available evidence suggests crossword puzzles increase student knowledge on objective measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

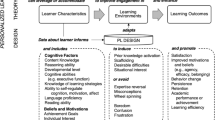

Health professions education (HPE), particularly in the setting of high-stakes standardised tests, may result in learners undertaking many practice questions. Gamification has been investigated as means by which to enhance the delivery of such content. Gamification involves “the application of elements of game playing (such as point scoring, competition with others, etc.) to other areas of activity, typically to encourage engagement” [1]. Studies in this area have provided promising results suggesting an increase in knowledge from educational games [2]. While the relative merits of gamification in medical education have been reviewed previously [3], different gamification styles present unique learning advantages and educators may benefit from nuanced information pertaining to the specific formats and delivery.

Crossword puzzles are word games in which numbered written clues or ‘stems’ are provided to the participant, and correspond to a grid in which the answers are written horizontally (across) or vertically (down), in a pattern such that shared letters intersect. Crossword puzzles are a widely used and familiar form of entertainment, appearing in newspapers, such as The New York Times since 1942 [4], and other popular periodicals. The linguistic morphology of crosswords may provide additional clues to answers beyond the information directly provided in the stem. These additional clues include the knowledge as to the number of letters in the answer, as well as any letters in the answer on the basis of previously solved stems for which answers intersect [5]. For HPE, crosswords can be used as a type of gamification to present information in a novel manner distinct from that of routine revision strategies, such as practice exam questions. The most effective means of delivery for the use of crosswords in HPE is unclear.

In view of this, we sought to answer the following question: in HPE students, what impact does the utilisation of crossword puzzles as a gamification strategy have on learning? In order to examine this question, we conducted a systematic review of the available literature. The primary aim of this study was to synthesise the evidence regarding the effectiveness of crosswords as a means of HPE. The secondary aim was to describe the characteristics of previously investigated crosswords (length, style, content & delivery) in the context of HPE.

Methods

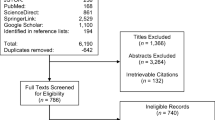

The development and reporting of this systematic review were in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see checklist in Supplementary Information) [6]. The protocol was registered prospectively with the PROSPERO registry (CRD42022378280). The databases PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library were searched from database inception to 25 November 2022. Search terms included: (crossword) AND (healthcare OR education OR teaching OR learning OR profession OR medical). Individual database search strings are available in Supplementary Information. Additionally, reference lists of included articles were searched for relevant studies.

Determination of whether studies met inclusion criteria was performed with a standardised form and in duplicate. Inclusion criteria were (1) Studies published in English; (2) Primary peer-reviewed research article (reviews and abstracts were excluded); (3) Delivered crossword puzzle(s) to individuals in a HPE pathway (including medical, nursing, pharmacy, and allied health, at the undergraduate or postgraduate level); (4) Presented data on the effectiveness of crosswords as a means of health profession education; and (5) Full-text of the article was available. Articles were screened for inclusion suitability based upon titles and abstracts. Studies that were likely to fulfil inclusion criteria, and in cases of uncertainty, were reviewed in full-text. Eligibility determination was conducted in duplicate (M.A., S.T., T.P., and S.B.). Instances of disagreement were resolved through discussion and consensus with a third author.

Data were extracted using a standardised spreadsheet, and included the following—participant characteristics: profession (e.g., medical, nursing, allied health), stage of training; study information: number of participants, response rate; crossword characteristics: topic/content (e.g., specifiers around anatomy, pharmacology, or specialty), length (i.e., number of rows/columns), stem style (e.g., question vs fill in the blank, full sentences vs sentence fragments), answers provided or not, circumstances of delivery (e.g., in teaching session vs during own time), undertaken individually or in group (or not specified), timing of delivery (e.g., relative to summative assessments); comparator characteristics (if relevant); and outcomes (educational impact, and student experience). The data are highlighted in the Supplementary Information. Methodological quality analysis and risk of bias assessment was performed using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) [7, 8]. The MERSQI tool was specifically designed for medical education contexts in which multiple study designs required appraisal, and considers the domains of study design, sampling, type of data, validity of evaluation, data analysis & outcomes [8]. Each domain is scored according to defined criteria, with a total score ranging from a minimum of 5 to maximum of 18, with a higher score indicating increasing methodological quality [8]. The MERSQI tool has been validated for use in medical education research [7], and is recommended for use in systematic reviews in medical education in an Association for Medical Education in Europe (AMEE) guide [9]. Methodological quality analysis utilising MERSQI was performed in duplicate with instances of disagreement resolved through discussion and consensus with a third investigator.

Results

Initial searches returned a total of 220 records. Of these, 29 fulfilled eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review, with others excluded as indicated in the flow diagram provided in Fig. 1. Included studies were from a diverse array of countries, including 14 from India [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], 4 from the United States of America [24,25,26,27], 2 from Malaysia [28, 29], 2 from Saudi Arabia [30, 31], 2 from Oman [32, 33], 2 from Iran [34, 35], and one from each of Canada [36], the United Arab Emirates [37] and Palestine [38]. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 38 [10] to 425 [21]. The structure and delivery of crosswords employed varied substantially. Methodological quality varied with MERSQI scores ranging from 5.5 to 15.5 (mean score 10.1). The most common methodological limitations were studies being conducted at a single institution [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] and utilising only cross-sectional or post-test-only methodologies [10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, 36, 37], and a number of studies also had unclear response rates [13, 15, 16, 19, 22, 24, 28, 30, 31, 34, 36, 37] (see Table 3, Supplementary Information D).

There were seven studies that report of the conduct of randomised trials [11, 12, 15, 20, 33, 35, 38]. Six examined student performance on knowledge-based assessments in the crossword groups compared to another group [11, 12, 15, 20, 35, 38]. In the study of speech therapy students by Zamani et al., both groups had similar performance prior to the intervention, and one month after the educational intervention the group that received crosswords had a significantly higher test score than the traditional teaching group (18.26 vs 16.10, P = 0.001) [35]. Similarly, in Gaikwad & Tankhiwale, the interventional group had an absolute learning gain of 33.9% as compared to the control group having an absolute learning gain of 18.55% (statistical significance not presented) [11]. These improvements in knowledge as evaluated through test scores were supported by other studies that examined trainees’ perceptions of their knowledge gain. For example, in Sannathimmappa et al. the proportion of students who "strongly agreed" with a statement that "Solving crossword puzzles improved my examination scores" was 69.3% [33]. Conversely, Shenoy & Rao compared crosswords to student led tutorials, and demonstrated improved test scores in the tutorial group, compared with that of the crossword group [20], though there was no control group who received traditional teaching methods to allow for comparison with standard practice. In the five studies that presented results regarding student experience, the responses were consistently positive with students reporting they enjoyed crosswords and would like to undertake further crosswords in future [11, 15, 20, 33, 35].

Eight studies fulfilled inclusion criteria that employed either single-group pre- and post-test analyses [16, 17, 19, 23, 24, 27, 37] or non-randomised two group studies [34]. Four studies presented data on the educational impact on test scores. Three studies demonstrated an increase in test scores following the application of crossword puzzles [23, 24, 34], noting that in one of these, crossword puzzles were not the sole intervention [24]. One study did not show an increase in test scores following crossword puzzle application [27]. Six studies presented results regarding student perceptions of educational effect, with all reporting that students felt that crossword puzzles had a positive impact on their learning [16, 17, 19, 23, 27, 37]. In the six studies that presented results regarding student experience, the responses were consistently positive in five [16, 17, 19, 23, 37], with one study reporting a range of responses from equivocal to positive [24].

There were 14 studies that conducted cross-sectional or post-test only evaluation [10, 13, 14, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 28,29,30,31,32, 36]. While these studies are generally of a lower quality of evidence to the previously described methodologies, the results of these studies were generally similar. The evidence that could be gleaned from these studies was typically more limited than those with randomised study designs. Only one study of this design reported the effect of crosswords on test performance, with that study reporting a positive effect in a cohort of learners in nursing programs [26]. The majority of these studies evaluated educational effect as reported by students. These reports were positive in all studies that evaluated such outcomes. The majority of trainees endorsed statements regarding the effect of crosswords on memory [10, 29], understanding [18, 29], and learning [13, 18, 29,30,31,32, 36]. The reported student experience was positive for the majority of participants in all studies of this type [10, 14, 18, 21, 25, 28,29,30,31,32, 36].

The length of examined crosswords varied substantially across the 19 studies which reported these characteristics [12, 16, 19, 23, 24, 27, 33, 37] ranging from 10 stems through to 60 stems, with the majority being 20 stems or fewer. Stems were most commonly presented as sentences or sentence fragments [10, 16, 22,23,24,25, 28, 30,31,32,33, 36, 37], with other methods including questions [24, 25] or fill-in the blanks [16, 23,24,25, 30, 32]. The majority of studies administered crosswords during teaching sessions [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 22,23,24,25, 28,29,30,31, 33, 35,36,37], as opposed to in students’ own time [26, 32, 34, 38]. The majority also administered the crosswords in groups ranging from two to twelve students in size [12,13,14, 16,17,18, 20, 22, 24, 25, 27,28,29, 31, 32, 36, 37], with fewer studies administering crosswords individually [10, 11, 15, 19, 23, 30, 33, 35]. Several studies commented on the collaborative nature of crossword completion as a significant positive factor relating to enjoyment [14, 23, 25, 30, 36]. Notably, studies also reported that having a competitive element to crosswords facilitated learning [10, 17, 28, 32], and it is noted that these implementation strategies are not mutually exclusive. Crosswords were most commonly administered via printed paper copies [10,11,12,13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 22, 25, 29, 30, 33, 35,36,37,38,39]. Several studies did not clearly specify whether delivery was via printed or digital copies [17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 28, 31]. Two studies described fully digital crossword delivery, utilising a web-based platform [32] or an Android app [34], designed by the respective research teams. The remaining two studies described hybrid approaches, with one study [21] utilising a combination of printed copies in addition to Google Forms & Google Classroom platforms, and the other [14] providing electronic PDF documents which students could elect to either print or edit digitally.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesised the available evidence, and found that crosswords have shown utility as an educational tool in a diverse array of learners, both with respect to HPE program and geography. Published studies have found generally positive results with respect to educational impact as evaluated through knowledge-based tests and student perceptions of knowledge gain. It was consistently reported that the majority of participants found crossword completion enjoyable. However, optimal crossword design for HPE has not been established. Knowledge of the ideal characteristics of crossword design can provide educators seeking to utilise this strategy with guidance as to how to develop these teaching materials. Examined crossword structures have included stems utilising sentences, sentence fragments, and fill-in-the-blank structures. The ideal method for crossword administration is uncertain, and is likely to vary based on local context. However, most studies have administered crosswords in group settings during teaching sessions. Participants have described collaborative completion as enjoyable, whilst also noting that the incorporation of competitive aspects to crosswords increased perceived effectiveness. Administration of crossword puzzles where learners compete in groups may therefore leverage the benefits of both strategies.

Efforts to make HPE more enjoyable may encourage the engagement and passion of learners, and have been explored through multiple avenues [40, 41]. It is evident that health professions students find crossword puzzles to be an enjoyable teaching method. However, it is relevant to consider the needs of learners at different stages. In the single included study (Dittus et al.) where the target group for crossword puzzles was practicing clinicians, the magnitude of overall satisfaction for the crossword puzzles themselves was reduced relative to traditional small group problem-based learning sessions, which may indicate less applicability of crosswords as a learning strategy with increasing levels of seniority [24]. The issues faced by practising health professionals in their daily work are likely to be of higher complexity, and thus, simpler education strategies such as crossword puzzles may be viewed as less relevant in this context, or there may be a perception that gamification is not a serious academic pursuit. However, the findings of this single study of 43 trainees should not be generalised too broadly without further research.

In evaluating outcomes, a modified Kirkpatrick four-level model can be utilised, which considers outcomes at the levels of reaction (satisfaction), learning (change in knowledge), behaviour and results (change in organizational practice) [42, 43]. The studies reviewed thus far have focussed on either reaction (level 1) or learning (level 2) based outcomes. Regarding level 1 outcomes on reactions, multiple studies reported that students subjectively judged crossword puzzles to have a positive impact on learning/educational outcomes, and felt that they should be included in courses/curriculum. Naturally, the subjective nature of these finding is an important limitation to consider. Furthermore, in the study by Sumanasekera et al. which compared crosswords with other active learning strategies, whilst 60–65% of respondents perceived that crossword puzzles helped retain concepts, only 6–7% of participants felt crosswords to be the most valuable learning method (with web-based interactive quizzes scoring the highest at 69–86%) [27]. Collaborative groupwork was described as contributing to the enjoyable nature of crosswords in multiple studies [14, 25, 30, 36]. Seemingly at odds with this result, several studies reported that students reported that a competitive aspect contributed to effectiveness [10, 17, 28, 32], although another noted more equivocal findings in this regard [37]. For medical students, there is other literature to support improved academic outcomes with competitive learning techniques [44]. However, a difference between professions may be a possible explanation, with a preference for collaboration in some cases, as two of the papers describing a benefit from collaboration involved pharmacy students [25, 30]. Further research could look further at the impact of crosswords in a competitive learning environment.

Regarding level 2 outcomes on learning [43], relatively fewer studies sought to assess the educational impact of crossword puzzles with regards to effects on knowledge as measured by objective test scores. Of those studies analysed, the majority indicate that crossword puzzles have a positive impact on student knowledge, though it is noted that this was not a unanimous finding [20, 27]. The study by Sumanasekera et al. did not demonstrate improved test scores following crossword puzzle administration, instead finding that videos and fill-in-the-blank tables were most effective in improving exam scores [27]. Further to this, Shenoy & Rao found that test scores were statistically significantly higher when learning was supported by student-led objective tutorials, compared with crossword puzzles [20]. These findings suggest a need for further high-quality research which compares crossword puzzles to other learning methods, looking specifically at objective measures of impact such as test scores.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Studies were limited to those published in English. Given the lexical nature of the topic of the review, the exclusion of non-English studies may limit the external generalisability of the findings for non-English speaking educators. Publication bias may have influenced the results of the review. The exclusion of an article due to the inability to retrieve such articles in full-text is also a limitation.

Future research in this area may also seek to examine the utility of crosswords at different stages of training. Such studies may be conducted comparing the utility of crosswords for junior medical students as compared to senior students, or postgraduate trainees. Additional studies examining different settings in which crosswords may be administered would also be useful. For example, no studies were identified that examined the use of crosswords for students specifically during clinical placements. Research examining the influence of different crossword structures (e.g., with respect to stem number) and designs (e.g., with respect to stem style, length & complexity) may also be useful, in order to determine if these variables impact upon learner reactions and outcomes from crossword administration. Such research should ideally seek to utilise robust randomised methodologies and evaluate effects on knowledge at least through the use of tests.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that crossword puzzles provide positive educational impact for learners in HPE contexts, particularly in terms of enjoyment. Learners find crossword puzzles to be an enjoyable learning activity, and have a positive perception regarding the impact on their learning. The available evidence suggests that crossword puzzles also have a positive educational impact as measured by knowledge-based assessments, though further research is warranted, given this finding was not unanimous, and was limited by methodological quality. The most commonly evaluated method of administration is in groups during teaching sessions. However, individual use and administration during students’ own time has also provided benefits. Further research may seek to examine variations of crosswords and crossword delivery to optimise potential educational gains.

References

Oxford English Dictionary: “Gamification". (https://www.oed.com) Accessed 7th April 2024.

Abdulmajed H, Park YS, Tekian A. Assessment of educational games for health professions: a systematic review of trends and outcomes. Med Teach. 2015;37(Suppl 1):S27-32. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1006609.

van Gaalen AEJ, Brouwer J, Schönrock-Adema J, Bouwkamp-Timmer T, Jaarsma ADC, Georgiadis JR. Gamification of health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(2):683–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-10000-3.

Dunlap DW. Birth of the Crossword, In: Times Insider, The New York Times (online). 2022. (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/17/insider/first-crossword.html) Accessed 21st April 2024.

Nickerson RS. Five down, Absquatulated: Crossword puzzle clues to how the mind works. Psychon Bull Rev. 2011;18(2):217–41. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-011-0069-x.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647.

Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1067–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000786.

Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1002–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.9.1002.

Sharma R, Gordon M, Dharamsi S, Gibbs T. Systematic reviews in medical education: A practical approach: AMEE Guide 94. Med Teach. 2015;37(2):108–24. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.970996.

Agarwal H, Singhal A, Yadav A. Crossword Puzzle: An Innovative Assessment Tool to Improve Learning of Students in Forensic Medicine. Medico-Legal Update. 2020;20:18–22.

Gaikwad N, Tankhiwale S. Crossword puzzles: self-learning tool in pharmacology. Perspect Med Educ. 2012;1(5–6):237–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-012-0033-0.

Gilani R, Niranjane P, Daigavane P, Bajaj P, Mankar N, Vishnani R. Crossword puzzle: An effective self-learning modality for dental undergraduates. J Datta Meghe Institute Med Sci Univ. 2020;15(3):397–401. https://doi.org/10.4103/jdmimsu.jdmimsu_233_20.

Gupta U, Gupta N, Sinha P, Gupta S, Mahdi F. Creative learning using crossword puzzle as learning tool for undergraduates in obstetrics and gynecology. J Contemp Med Edu. 2015. https://doi.org/10.5455/jcme.20150508051013.

Hirkani M, Hegde G, Kamath R, Sonwane T, Angane E, Gajbhiye R. Strategies to foster group cohesion in online learning environments: use of crossword and Hybrid Medical Pictionary. Adv Physiol Educ. 2022;46(1):30–4. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00116.2021.

Kolte S, Jadhav PR, Deshmukh YA, Patil A. Effectiveness of crossword puzzle as an adjunct tool for active learning and critical thinking in Pharmacology. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2017;6(6):1431–1436. https://doi.org/10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20172236.

Kumar L, Bangera S, Thalenjeri P. Introducing innovative crossword puzzles in undergraduate physiology teaching- learning process. Archives Med Health Sci. 2015;3:127. https://doi.org/10.4103/2321-4848.154964.

Malini M, Sudhir K, Narasimhaswamy N. Crossword puzzle as a tool to enhance learning among students in a medical school. Nat J Physiol, Pharmacy Pharmacol. 2019;9(8):1–797. https://doi.org/10.5455/njppp.2019.9.0620304062019.

Nazeer M, Sultana R, Ahmed M, Asad M, Sami W, Hattiwale H, et al. Crossword puzzles as an active learning mode for student directed learning in anatomy teaching: Medical undergraduate perceptions. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2018;7(10):12–9.

Patrick S, Vishwakarma K, Giri VP, Datta D, Kumawat P, Singh P, et al. The usefulness of crossword puzzle as a self-learning tool in pharmacology. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2018;6(4):181–5.

Shenoy D, Rao D. Crossword puzzles versus Student-Led Objective Tutorials (SLOT) as innovative pedagogies in undergraduate medical education. Scientia Medica. 2021;31:e37105. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-6108.2021.1.37105.

Singh Matreja P, Kaur J, Yadav L. Acceptability of the use of crossword puzzles as an assessment method in Pharmacology. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2021;9(3):154–9. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2021.90517.1413.

Chitturi R, Krupal V, Potti R, Inuganti R. A Study on perception of students regarding newer teaching methods in medical education. J Clin Diagn Res. 2020;14(8):1–4. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2020/44221.13925.

Patel J, Dave D. Implementation and evaluation of puzzle-based learning in the first MBBS students. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2019;9(6):519–23. https://doi.org/10.5455/njppp.2019.9.0309628032019.

Dittus C, Grover V, Panagopoulos G, Jhaveri K. Chief’s seminar: turning interns into clinicians. F1000Res. 2014;3:213. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.5221.1.

Shah S, Lynch LM, Macias-Moriarity LZ. Crossword puzzles as a tool to enhance learning about anti-ulcer agents. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):117. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7407117.

Torres ER, Williams PR, Kassahun-Yimer W, Gordy XZ. Crossword Puzzles and Knowledge Retention. J Eff Teach High Ed. 2022;5(1):18–29. https://doi.org/10.36021/jethe.v5i1.244.

Sumanasekera W, Turner C, Ly K, Hoang P, Jent T, Sumanasekera T. Evaluation of multiple active learning strategies in a pharmacology course. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2020;12(1):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2019.10.016.

Htwe TT, Sabaridah I, Rajyaguru KM, Mazidah AM. Pathology crossword competition: an active and easy way of learning pathology in undergraduate medical education. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(2):121–3.

Saran R, Kumar S. Use of crossword puzzle as a teaching aid to facilitate active learning in dental materials. Med Sci. 2015;5(4):456–7.

Bawazeer G, Sales I, Albogami H, Aldemerdash A, Mahmoud M, Aljohani MA, et al. Crossword puzzle as a learning tool to enhance learning about anticoagulant therapeutics. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):267. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03348-0.

Agarwal A, Rao S. Creative pathology teaching with word puzzles until students learn: a study in a medical university. Asian J Res Med Pharmaceut Sci. 2017;2:1–7. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJRIMPS/2017/38416.

Qutieshat A, Al-Harthy N, Singh G, Chopra V, Aouididi R, Arfaoui R, et al. Interactive crossword puzzles as an adjunct tool in teaching undergraduate dental students. Int J Dent. 2022;2022:8385608. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8385608.

Sannathimmappa M, Nambiar V, Gowda S, Arvindakshan R. Crossword puzzle: a tool for enhancing medical students’ learning in microbiology and immunology. Int J Res Med Sci. 2018;6:756. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20180591.

Katebi MS, Leilimosalanejad BL. Development of midwifery emergency curriculum by the clinical case-based crossword games simulation and learning in midwifery students. Pakistan J Med Health Sci. 2020;14:1126–30.

Zamani P, BiparvaHaghighi S, Ravanbakhsh M. The use of crossword puzzles as an educational tool. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2021;9(2):102–8. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2021.87911.1330.

Saxena A, Nesbitt R, Pahwa P, Mills S. Crossword puzzles active learning in undergraduate pathology and medical education. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1457–62.

Bryant JD. Crossword Puzzles - Entertaining tool to reinforce lecture content in undergraduate physiology teaching. Int J Biomed Res. 2016;7:346–9.

Shawahna R, Jaber M. Crossword puzzles improve learning of Palestinian nursing students about pharmacology of epilepsy: Results of a randomized controlled study. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;106:107024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107024.

Sumanasekera W, Turner C, Ly K, Hoang P, Jent T, Sumanasekera T. Evaluation of multiple active learning strategies in a pharmacology course. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;12(1):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2019.10.016.

Howarth-Hockey G, Stride P. Can medical education be fun as well as educational? BMJ. 2002;325(7378):1453–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1453.

Gifford H, Varatharaj A. The ELEPHANT criteria in medical education: Can medical education be fun? Med Teach. 2010;32(3):195–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421591003614866.

Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600902976.

Kirkpatrick DL. The Four Levels of Evaluation. In: Brown SM, Seidner CJ, editors. Evaluating Corporate Training: Models and Issues. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands; 1998. p. 95–112.

Corell A, Regueras LM, Verdú E, Verdú MJ, de Castro JP. Effects of competitive learning tools on medical students: A case study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0194096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194096.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arnold, M., Tan, S., Pakos, T. et al. Evidence-Based Crossword Puzzles for Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review. Med.Sci.Educ. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02085-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02085-x