Abstract

Most medical schools have transitioned from discipline-based to integrated curricula. Although the adoption of integrated examinations usually accompanies this change, stand-alone practical examinations are often retained for disciplines such as gross anatomy and histology. Due to a variety of internal and external factors, faculty at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine recently began to phase out stand-alone histology practical examinations in favor of an integrated approach to testing. The purpose of this study was to evaluate this change by (1) comparing examination performance on histology questions administered as part of stand-alone versus integrated examinations and (2) ascertaining whether students alter their approach to learning histology content based on the examination format. Data from two courses over a period ranging from 2018 to 2022 were used to evaluate these questions. Results indicated histology question performance initially dropped after being included on integrated examinations. Stratification of students by class rank revealed this change had a greater impact on lower-performing students. Longitudinal data showed that performance 2 years after the change yielded scores similar to previous standards. Despite the initial performance drop, survey results indicate students overwhelmingly prefer when histology is included on integrated examinations. Additionally, students described alterations in study approaches that align with what is known to promote better long-term retention. The results presented in this study have important implications for those at other institutions who are considering making similar changes in assessment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most significant changes to take place in the approach to teaching the first 2 years of medical education (pre-clerkship) in the last several decades is the conversion of discipline-based to integrated curricula. Teaching basic science content in conjunction with clinical disciplines provides medical students motivation to learn important basic science content and encourages faculty to organize material in a way that is beneficial to future physicians [1]. Although curricula at individual institutions vary, in many cases, curricular integration includes integrated examinations. Assessing content that traditionally involves a laboratory component, such as gross anatomy and histology, is often an exception and retains its own stand-alone, practical examination (e.g., [2]).

In parallel with curricular changes, technological advances have made a significant impact on medical education. In particular, histology (microscopic anatomy) instruction has transformed dramatically over the past 20 years due to the near universal implementation of virtual microscopy to supplement or replace study of histology using glass slides viewed through microscopes [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Although the implementation was gradual, by 2017, most medical schools in the USA had incorporated virtual microscopy into the teaching of histology [14].

Evolution of Histology Education at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Histology instruction at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine (UCCOM) underwent a substantial shift following the transition from stand-alone courses to an integrated, organ-systems-based curriculum in 2011. By that point, the implementation of virtual microscopy had already begun, starting with the use of virtual slides as a supplement to glass slides and microscopes. Alongside this change was a shift from histology being taught in a traditional, lecture/laboratory format to histology instruction being almost entirely virtual via self-study modules. Previous research has assessed the impact of this alteration, which was largely positive in terms of student outcomes and preference [15]. When this change occurred around 2016, histology was taught within the integrated courses, but still tested independently on stand-alone, practical examinations. As the curriculum continued to evolve, there were several factors that led to a push for histology content to be included on the integrated, computer-based lecture examinations. First, a declining emphasis on microscope-related skills resulted in digital slides being used more frequently on histology examinations. This brought up the question of whether histology needed a separate examination when digital images of slides could easily be included on the computer-based, integrated examinations. Second, having histology tested separately allowed students to study a large volume of material over a short period of time leading up to the examination. Pedagogically, this approach is not favorable for long-term retention [16, 17]. Including histology on integrated exams would, in theory, require students to consistently review the material and integrate it with related lecture content. Lastly, including histology on integrated examinations would eliminate the former stand-alone practical examination, providing both students and course directors with greater flexibility in scheduling.

When making a substantial change in assessment strategy, it is critical to evaluate how student learning outcomes are influenced. The purpose of this study is to determine how student performance, study approach, and student preference were impacted when histology was assessed as part of integrated versus stand-alone examinations. In addition to overall trends, this study also investigates whether students at different levels of academic achievement were affected equally and if any temporal trends in student performance exist across the transition in assessment strategy.

Materials and Methods

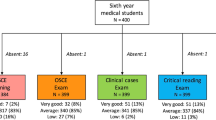

To investigate the transition from stand-alone to integrated histology examinations, several different cohorts and two different courses at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine were considered (Table 1). The academic years investigated ranged from 2018 to 2022. Over this period, the examination format of histology changed from stand-alone to integrated examinations. The first course to incorporate this transition in 2020 was the Gastrointestinal, Endocrine, and Reproduction (GER) course, which is part of the second-year medical school curriculum. In 2022, the Musculoskeletal-Integumentary (MSK) course, which is part of the first-year medical school curriculum, also shifted from stand-alone to integrated histology examinations. To evaluate whether student performance was impacted by this change in assessment format, data from stand-alone examinations that occurred 2 years prior to these transition points were included.

While similar changes occurred in other courses in the curriculum, the GER and MSK courses were selected for this study because the assessment items over this transitional period were the most comparable in these courses. Only questions that were exactly the same before and after the assessment format change were included since that provides the most direct comparison. In total, 18 questions in the GER course and 16 questions in the MSK course met this criterion. When histology was included on integrated examinations, both courses employed assessment strategies that spread the histology content out over three examinations that were each separated by 2-week time periods.

Study Design

Examination data were investigated using several different approaches. The first was to compare overall student performance on histology questions when delivered as a stand-alone versus part of an integrated examination within each course. Next, class rank was used to group students in each cohort into an upper and lower 50%. This was done to determine if the change in examination format disproportionally affected higher- or lower-performing students. For this study, class rank reflects a calculation that took place at the end of the academic year a given class was enrolled in either the MSK or GER course. This calculation includes all course grades leading up to that point in time. Lastly, student performance was investigated by year to determine if there were any temporal trends that might be obscured with pooled data.

In addition to examination data, students enrolled in the 2022 MSK course were surveyed to elicit their feedback on the change in assessment strategy. This group of students was selected because the course that occurs just prior to MSK, Fundamentals of Cellular Medicine, still tests histology as a stand-alone examination. At the end of the MSK course, students were given an open-ended question asking them to comment on whether their approach to studying histology changed when it was tested on an integrated versus stand-alone examination.

Statistical Methods

All examination data were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with scores on the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) used as a covariate. This was done to account for the possibility that differences in student aptitude could impact the results. When applicable, a Bonferroni post hoc test was used to evaluate pairwise comparisons. The effect size for ANCOVA results are reported as eta squared n2, which was calculated by dividing the sum of squares between by the sum of squares total [18]. Cohen [19] suggests that values should be interpreted as follows: 0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, and 0.14 = large. All quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Cort., Armonk, NY). The student survey results were analyzed and reported using thematic analysis [20]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine (IRB#2021–1061).

Results

Overall Comparison

The mean score for the two cohorts that took the stand-alone histology examination in the GER course was 90.8 ± 8.8%. In contrast, when the same questions were asked as part of integrated examinations, the average was 86.4 ± 11.8%. ANCOVA results indicated this difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01) with a small to medium effect size n2=0.043 (Table 2). In the MSK course, similar results were observed. The class average for students who took stand-alone histology examinations was 92.2 ± 8.2% whereas students who were assessed on histology as part of the integrated examinations averaged 81.8 ± 11.1%. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01) with a large effect size n2=0.201 (Table 2).

Comparison by Class Standing

To further investigate the difference in performance, students within each course and cohort were divided into an upper and lower 50% according to class rank. In the GER course, this revealed that students in the upper 50% of the class who were tested on histology as a stand-alone examination averaged 94.7 ± 5.1% whereas students in the upper 50% who were tested as part of an integrated examination averaged 91.0 ± 7.4%. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01) with a medium effect size n2=0.068. A similar pattern was also present among students who ranked in the lower 50% of the class, where the stand-alone examination average was 87.1 ± 10.1% compared to an integrated examination average of 81.8 ± 13.4%. This difference was also statistically significant (p < 0.01) with small-medium effect size n2=0.044 (Table 3).

In the MSK course, students in the upper 50% who took stand-alone histology examinations averaged 95.2 ± 5.5% whereas students in the upper 50% who took an integrated histology examination averaged 88.5 ± 9.2%. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01) with a large effect size n2=0.160.Students in the lower 50% who took stand-alone examinations averaged 89.2 ± 9.3%, while students in the lower 50% who took integrated histology examinations averaged 74.7 ± 13.2%. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01) with a large effect size n2=0.284 (Table 3).

Comparison by Cohort

Examination averages by cohort were considered to determine if there were any patterns in the data over time. Within the GER course, ANCOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in examination scores between the five cohorts (p < 0.01) with a medium effect size (n2 = 0.074). While there were significant differences between several post hoc comparisons, the most notable finding was that the examination averages the initial year histology was integrated were significantly different than every other year that was analyzed (Table 4). The longitudinal trend of scores in the GER course is also visualized in Fig. 1. This illustrates how the initial decline in performance during the first year of integrated examinations is followed by results in the two most recent years that are comparable to when the examinations were delivered in a stand-alone format.

In the MSK course, there was a statistically significant difference between the three cohorts that were compared (p < 0.01) with a large effect size n2=0.202 Post hoc tests revealed that both groups who took the stand-alone histology examination performed significantly better than those who took the integrated examination (Table 4).

Student Survey

The response rate for the survey was 70% (40/57). When students were asked for feedback on histology being assessed as part of a stand-alone versus integrated examination, two themes emerged. The first had to do with study habits. Of the twenty-nine students who specifically commented on their study routine, 69% indicated that having histology as part of an integrated examination forced them to review the content more frequently, whereas the remaining 31% indicated that their study habits did not change. The second theme that emerged was related to overall preference. In this case, 86% of the twenty-one students who commented on this theme indicated they preferred when histology was tested on integrated examinations. Those who preferred the integrated format often commented that it forced them to continuously review the material, and while causing more work initially, it was less stressful than “cramming” neglected material shortly before a stand-alone examination. Those who preferred stand-alone examinations commented that this format allowed them to better organize their time and focus on histology content when preparing for an examination that assessed the material all at once.

Discussion

This study explored outcomes related to testing histology on integrated versus stand-alone examination formats. Results indicate that overall, student performance on histology questions was higher when they were delivered on a stand-alone examination. Investigation by cohort revealed temporal trends in the GER course that show an improvement over time in the average scores of histology questions on integrated examinations. Another aspect considered in this study was whether the change in testing format of histology impacted students differently based on their academic class rank. While significant differences were identified among both the upper and lower 50% of the class, the decrease in performance was larger among the lower 50% after histology was included on integrated examinations. This finding was particularly evident in the MSK course, where students in the lower 50% of the class performed 14.5% lower on integrated examinations compared to 6.7% lower among those in the upper 50% of the class.

On the surface, these results appear to suggest that testing histology in a stand-alone format produces better learning outcomes. However, academic performance is only one aspect of a much larger picture. Survey data collected from this study show that students overwhelmingly prefer when histology is included on integrated examinations. Numerous students commented how testing histology on integrated examinations forced them to revisit the material on a regular basis, which, pedagogically, has benefits from the standpoint of long-term retention [16, 17]. Assessment integration may also influence student preparation strategies, subsequently impacting performance [21]. Beyond material retention, an integrated approach has also been shown to facilitate the transfer of conceptual knowledge to clinical applications when assimilated in a longitudinal manner [22, 23].

When contextualizing the performance outcomes presented in this study, it is important to consider the larger picture of whether the observed differences translate to large knowledge gaps. To keep the comparisons as consistent as possible, only examination questions that were identical and asked every year were included in this study. This resulted in a relatively small number of overall questions that were investigated. This point is critical for interpreting the results because it means that a statistically significant difference of a 4.4% lower average performance on integrated examinations in GER translates to less than a single examination question. While the difference is slightly more notable in MSK, it begs the question of whether the slight drop in immediately observable performance might be outweighed by potential long-term benefits. Most agree that student study habits are driven by assessment [24,25,26,27,28]. Thus, including histology as part of an integrated examination encourages students to integrate material, which has been shown to have a positive influence on learning [29].

Comparing the results of this study to previous findings is challenging since there are few examples in the literature that evaluate the impact that shifts from stand-alone to integrated testing have on student performance. Thompson et al. [30] found that student performance decreased when discipline-integrated assessments were introduced among second-year medical students. However, further inquiry revealed that the integrated examinations tested a greater proportion of higher-order concepts, which likely explained the difference in performance. The current study avoided confounding factors such as this by only including identical questions. Hudson and Tonkin [31] investigated the impact of a move from discipline-specific to integrated examinations and found overall positive outcomes. However, the authors focused on examination validity rather than student performance. In a recent paper, a decrease in the amount of time dedicated to histology and a reduction in the number of histology questions included on assessments was shown to negatively impact student performance, particularly among students in the lower quartile of the class [32]. The authors offer two possible explanations for their overall findings: students spent less time studying histology, and students were no longer informed of their histology-specific performance on integrated examinations, which may have made it difficult to self-identify areas in need of improvement. The latter point is relevant to this study since students went from receiving a separate histology practical examination score to a histology score that was a relatively small component of a larger examination. While students were provided with a score report that included a breakdown of histology question performance, it is unclear whether they use this information to modify their study strategies.

This study focused on two different courses, one of which takes place in the first year of the curriculum (MSK) whereas the other course (GER) is in the second year. While the results from these courses were not distinctly different, the decrease in performance was more pronounced in the MSK course. When comparing the performance of first-year to second-year medical students, it is important to note that educational experience may impact student preparation and outcomes on the integrated examinations. For example, the level of a student’s previous exposure to coursework can have a substantial influence on the understanding of the material and assessment outcomes [33, 34]. Therefore, second-year students, having significant experience with medical school course materials and a greater appreciation for integrated assessments, may have an increased ability to perform well on integrated examinations when compared to their first-year counterparts. Another possibility that could explain the improvement in scores over time in the GER course is updated study materials. To improve the subsequent cohorts’ academic performance, students often create and “pass down” study resources. It is possible that changes in curricular content or assessment strategies might not be immediately reflected in these materials. As a result, students who rely heavily on these resources may not allocate enough time studying content that is different from the previous year. Additional years of data from the MSK course could provide further insight into whether this could explain the temporal trends observed in the GER course.

A finding from the present study that is difficult to explain is why students in the lower 50% of the class were differentially impacted by the histology assessment strategy change. Previous studies have suggested several potential factors that differentiate lower- and higher-performing learners, including differences in anxiety, test-taking strategies, study strategies, and motivation [35,36,37,38]. However, these only serve as general explanations for potential sources of the difference. Why the gap between upper- and lower-performing students would increase with integrated histology examinations requires further inquiry. At present, the most logical explanation is that students who are struggling to keep up with course material choose to place less emphasis on studying histology when it is on integrated examinations because it represents only a small portion of a larger examination. Student survey comments lend some support to this possibility, as two different students specifically stated that studying histology was not a priority when tested on an integrated examination because there was so much additional material they needed to learn. A more targeted study is needed to further explore this theory.

Limitations

Despite attempts to create a controlled study design, there are a number of factors that limit the interpretation of the findings presented in this study. First, this study focused on two courses that are part of a much larger curriculum. While this was done because these courses provided the most direct comparison, any other curricular changes that occurred over the study period could not be accounted for in the results. This includes external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and its influence on the delivery of the curriculum. Since histology was assigned as self-study modules over the entire study period, COVID-19 likely had less of an effect than other areas. Nonetheless, there are implications related to this that extend beyond the delivery of material that could have impacted the results. Another issue is the relatively small number of questions included in this study. Previous research suggests that 25–30 examination items are needed to reach adequately reliability [39]. Thus, it is not certain how well the identical items selected for use in this study represent overall histology knowledge. In addition, the study period for the MSK course was short, with only a single year of integrated examination data that were available. Additional data points will help further evaluate the trends observed in this study. Lastly, survey data was retrospective in the sense that students were asked to compare experiences that occurred months apart. It is possible that students did not accurately remember, for example, the way they studied months prior for a stand-alone compared to an integrated examination.

Conclusion

Evaluating the impact that changes in assessment strategy have on student performance is a critical step in quality control and improvement. Results from the present study indicate that student performance on histology questions declined when they were included as part of integrated examination. Trends observed in the longitudinal data in the GER course showed that the initial drop in student performance was followed by improvement that resulted in averages that reached levels similar to previous standards within 2 years. While the reason for the initial decline in scores is not entirely clear, several factors are suggested, including shifts in the amount of time devoted to studying histology as well as a transitional period where student-generated study resources do not align with curricular/assessment changes. Although the shift to integrated histology examinations did not produce evidence of benefits from a student performance standpoint, the change was viewed as largely positive from a student perspective and eliminating the stand-alone examination provided both students and course directors more flexibility in scheduling. It is hoped that this study will provide insight for those at other institutions who are considering a similar change in assessment strategies.

Availability of Data and Material

Data used in this study are available upon request.

References

Brauer DG, Ferguson KJ. The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):312–22.

Klement BJ, Paulsen DF, Wineski LE. Anatomy as the backbone of an integrated first year medical curriculum: design and implementation. Anat Sci Educ. 2011;4(3):157–69.

Harris T, Leaven T, Heidger P, Kreiter C, Duncan J, Dick F. Comparison of a virtual microscope laboratory to a regular microscope laboratory for teaching histology. Anat Rec. 2001;265(1):10–4.

Heidger PM Jr, Dee F, Consoer D, Leaven T, Duncan J, Kreiter C. Integrated approach to teaching and testing in histology with real and virtual imaging. Anat Rec. 2002;269(2):107–12.

Blake CA, Lavoie HA, Millette CF. Teaching medical histology at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine: transition to virtual slides and virtual microscopes. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2003;275(1):196–206.

Krippendorf BB, Lough J. Complete and rapid switch from light microscopy to virtual microscopy for teaching medical histology. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2005;285(1):19–25.

Bloodgood RA, Ogilvie RW. Trends in histology laboratory teaching in United States medical schools. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2006;289(5):169–75.

Braun MW, Kearns KD. Improved learning efficiency and increased student collaboration through use of virtual microscopy in the teaching of human pathology. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1(6):240–6.

Husmann PR, O’Loughlin VD, Braun MW. Quantitative and qualitative changes in teaching histology by means of virtual microscopy in an introductory course in human anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2(5):218–26.

Paulsen FP, Eichhorn M, Bräuer L. Virtual microscopy-the future of teaching histology in the medical curriculum? Ann Anat. 2010;192(6):378–82.

Helle L, Nivala M, Kronqvist P. More technology, better learning resources, better learning? Lessons from adopting virtual microscopy in undergraduate medical education. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6(2):73–80.

Mione S, Valcke M, Cornelissen M. Evaluation of virtual microscopy in medical histology teaching. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6(5):307–15.

Drake RL, McBride JM, Pawlina W. An update on the status of anatomical sciences education in United States medical schools. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7(4):321–5.

McBride JM, Drake RL. National survey on anatomical sciences in medical education. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(1):7–14.

Thompson AR, Lowrie DJ Jr. An evaluation of outcomes following the replacement of traditional histology laboratories with self-study modules. Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10(3):276–85.

Karpicke JD, Roediger HL. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science. 2008;319(5865):966–8.

Karpicke JD, Roediger HL. Repeated retrieval during learning is the key to long-term retention. J Mem Lang. 2007;57(2):151–62.

Levine TR, Hullett CR. Eta squared, partial eta squared, and misreporting of effect size in communication research. Hum Commun Res. 2002;28(4):612–25.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1988.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Husmann PR, Gibson DP, Davis EM. Changing study strategies with revised anatomy curricula: a move for better or worse? Med Sci Edu. 2020;30(3):1231–43.

Lim-Dunham JE, Ensminger DC, McNulty JA, Hoyt AE, Chandrasekhar AJ. A vertically integrated online radiology curriculum developed as a cognitive apprenticeship: impact on student performance and learning. Acad Radiol. 2016;23(2):252–61.

Di Salvo DN, Clarke PD, Cho CH, Alexander EK. Redesign and implementation of the radiology clerkship: from rraditional to longitudinal and integrative. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):413–20.

Wormald BW, Schoeman S, Somasunderam A, Penn M. Assessment drives learning: an unavoidable truth? Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2(5):199–204.

Wood T. Assessment not only drives learning, it may also help learning. Med Educ. 2009;43(1):5–6.

McLachlan JC. The relationship between assessment and learning. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):716–7.

Jensen JL, McDaniel MA, Woodard SM, Kummer TA. Teaching to the test … or testing to teach: exams requiring higher order thinking skills encourage greater conceptual understanding. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):307–29.

Kromann CB, Jensen ML, Ringsted C. The effect of testing on skills learning. Med Educ. 2009;43(1):21–7.

Van der Veken J, Valcke M, De Maeseneer J, Schuwirth L, Derese A. Impact on knowledge acquisition of the transition from a conventional to an integrated contextual medical curriculum. Med Educ. 2009;43(7):704–13.

Thompson AR, Braun MW, O’Loughlin VD. A comparison of student performance on discipline-specific versus integrated exams in a medical school course. Adv Physiol Educ. 2013;37(4):370–6.

Hudson JN, Tonkin AL. Evaluating the impact of moving from discipline-based to integrated assessment. Med Educ. 2004;38(8):832–43.

Gribbin W, Wilson EA, McTaggart S, Hortsch M. Histology education in an integrated, time-restricted medical curriculum: academic outcomes and students’ study adaptations. Anat Sci Educ. 2022;15:671–84.

McNulty MA, Lazarus MD. An anatomy pre-course predicts student performance in a professional veterinary anatomy curriculum. J Vet Med Educ. 2018;45(3):330–42.

Forester JP, McWhorter DL, Cole MS. The relationship between premedical coursework in gross anatomy and histology and medical school performance in gross anatomy and histology. Clin Anat. 2002;15(2):160–4.

Khalil MA-O, Williams SE, Hawkins HG. The use of Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI) to investigate differences between low vs high academically performing medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2019;30(1):287–92.

Albaili MA. Differences among low-, average- and high-achieving college students on learning and study strategies. Educ Psych. 1997;17:171–7.

Biggs J, Kember D Fau - Leung DY, Leung DY. The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br J Educ Psychol. 2001;71(0007–0998 (Print)):133–49.

May W, Chung E-K, Elliott D, Fisher D. The relationship between medical students’ learning approaches and performance on a summative high-stakes clinical performance examination. MedTeach. 2012;34(4):e236–41.

Byram JN, Seifert MF, Brooks WS, Fraser-Cotlin L, Thorp LE, Williams JM, et al. Using generalizability analysis to estimate parameters for anatomy assessments: a multi-institutional study. Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10(2):109–19.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andi Oaks for the assistance in collecting the data used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: ART and DL; data analysis: ART; manuscript text: ART, DL, and MU; figures and tables: ART. All of the authors have reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine (IRB#2021-1061). Informed consent was not required for this study.

Consent for Publication

Only deidentified, aggregate data were used in this study. Per institutional IRB guidelines, consent for publication was not required for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, A.R., Lowrie, D.J. & Ubani, M. The Effect of Histology Examination Format on Medical Student Preparation and Performance: Stand-Alone Versus Integrated Examinations. Med.Sci.Educ. 33, 165–172 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01731-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01731-0