Abstract

Empathy is the basis of a patient-physician relationship; however, this is being lost by students throughout medical training. Immersive virtual reality that allows individuals to viscerally experience anything from another person’s point of view has the potential to reverse the erosion of empathy and improve clinical practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Empathy is arguably the “backbone” of the patient-physician relationship, as it has been shown to have numerous positive clinical outcomes for both the patient and the provider. Empathetic care giving is associated with improved patient satisfaction, compliance, and outcomes; clinical competence, career satisfaction, and burnout reduction; as well as diminished medical errors and litigation claims [1]. Unfortunately, previous studies have shown erosion in empathy and compassion during both medical school and residency training, with more recent studies showing a less bleak forecast [2]. As such, various pedagogical methods including balint groups, small groups, workshops, humanities exposure, standardized patient encounters, roleplaying, and reflection have been employed to improve empathetic skills with varying success [3]. However, there is no current standard for empathy/compassion training within medical education. Given these findings, it is timely and important to look at innovative teaching platforms for enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical and health professional education.

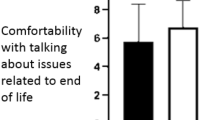

As an experiential learning platform, virtual reality has been dubbed the “ultimate empathy machine” as it has been shown to invoke empathy through a process of total embodiment which allows users to virtually step into the shoes of others and see the world from their perspective. In addition to generating empathy, virtual body transfers have been shown to reduce cognitive biases, adopt new attitudes, provoke behavioral responses, increase self-compassion, and influence career choices [4]. Compared to training with people (peers, standardized patients, or patients), virtual reality software may be more accessible, reliable, and economical in the long run. One such promising commercial software, Embodied Labs (https://embodiedlabs.com), allows users to “become” different patients with terminal lung cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or macular degeneration [5]. Using Oculus Rift virtual reality goggles, users embody these patients as they undergo the health care process, experience disease symptoms, navigate family dynamics, and engage with various care teams. Thus far, we have piloted three labs to gather feedback on the usability, feasibility, and efficacy of this tool as an overall learning platform utilizing the company’s standard pre/post survey tools and asking about overall learning experience with an internal questionnaire (Table 1). Overall, students have been greatly satisfied with the experience, rating it as a highly valuable learning experience and requesting incorporation into future curricula. Only a few students with very low visual acuity or with a severe motion sickness were unable to complete the modules using the virtual reality goggles. Results on post surveys generated by the software indicated a self-reported gain in understanding of the disease process, what patients endure, and the challenges experienced by family members. In feedback and focus groups, we noticed a high level of immersion indicated by first-person language (as if they were actually the patient), empathetic discourse about the patient and family members, and a change in emotional perspectives. Our preliminary results warrant further exploration with respect to empathy, utilization as a clinical skills training tool, and long-term benefits.

With virtual reality software and the development of artificial intelligence, the old adage of walking a mile in someone else’s shoes is now possible and should be a part of requisite medical and health professional training. As stand-alone experiences, they can provide powerful emotional responses related to understanding, empathy, and compassion towards patients and their family members. Moreover, such experiences could be coupled with clinical skills training, such as history taking and communication strategies, to determine the extent to which they can influence clinical practice. Given the portability of the technology, similar experiences could be brought into practice settings for residents, physicians, and other health care professionals. This technology could even be extended into the community and used by leaders, emergency response personnel, health care staff, informal caregivers, and support groups. Furthermore, this can be used as a distance teaching tool through software mirroring that would allows a singular user to share their user experience with a large group of distance learners. Thus, the potential of virtual reality to improve the compassion crisis within health care seems limitless.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Hojat M. Empathy in health professions education and patient care. Springer International Publishing; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27625-0.

Ferreira-Valente A, Monteiro JS, Barbosa RM, Salgueira A, Costa P, Costa MJ. [1] Ferreira-Valente A, Monteiro JS, Barbosa RM, Salgueira A, Costa P, Costa MJ. Clarifying changes in student empathy throughout medical school: a scoping review. Adv Heal Sci Educ 2017;22:1293–313. 10.1007/s10459-016-9704-7.Clarifying ch. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2017;22:1293–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9704-7.

Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, Roberts MB, Kilgannon H, Trzeciak S, et al. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221412.

Louie AK, Coverdale JH, Balon R, Beresin EV, Brenner AM, Guerrero APS, et al. Enhancing empathy: a role for virtual reality? Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:747–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-018-0995-2.

Washington E, Shaw C. The effects of a VR intervention on career interest, empathy, communication skills, and learning with second-year medical students. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27986-8_7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Carrie Elzie and Jacqueline Shaia. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Carrie Elzie and Jacqueline Shaia commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of Eastern Virginia Medical School (IRB # 19-10-WC-0246).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elzie, C.A., Shaia, J. Virtually Walking in a Patient’s Shoes—the Path to Empathy?. Med.Sci.Educ. 30, 1737–1739 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01101-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01101-0