Abstract

Purpose

Indigenous patients experience a variety of healthcare challenges including accessing and receiving needed healthcare services, as well as experiencing disproportionate amounts of bias and discrimination within the healthcare system. In an effort to improve patient-provider interactions and reduce bias towards Indigenous patients, a curriculum was developed to improve first-year medical students’ Indigenous health knowledge.

Method

Two cohorts of students were assessed for their Indigenous health knowledge, cultural intelligence, ethnocultural empathy, and social justice beliefs before the lecture series, directly after, and 6 months later.

Results

Results of paired t test analysis revealed that Indigenous health knowledge significantly improved after the training and 6 months later. Some improvements were noted in the areas of cultural intelligence and ethnocultural empathy in the second cohort.

Conclusions

It is feasible to teach and improve Indigenous-specific health knowledge of medical students using a brief intervention of lectures. However, other critical components of culturally appropriate care including social justice beliefs and actions, ethnocultural empathy, and cultural humility may require increased and immersed cultural training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“The ultimate aim of a curriculum on disparities is that learners develop a professional commitment to eliminating inequities in health care quality and understand and accept their role in eliminating racial and ethnic healthcare disparities [1].”

In the USA, IndigenousFootnote 1 people receive poorer healthcare compared to non-Indigenous people and have worse health outcomes [2]. These disparities occur due to reduced access to primary care, use of lower-quality healthcare facilities, language barriers, and economic and educational disparities [3, 4]. In addition, ethnicity and race also play a role in the quality of care and treatment patients receive within the medical system [5]. When controlling for access-related factors, stereotyping, discrimination, and implicit bias are associated with health disparities for racial and ethnic minorities [6]. For instance, a survey of implicit bias among 154 providers found that one third agreed with negative stereotypes about Indigenous people; 84% both preferred non-Hispanic White patients to Indigenous patients and believed Indigenous children were more challenging and their caregivers less compliant compared to non-Hispanic White patients [7]. These biased beliefs have consequences for patients’ outcomes [8] and negatively affects patient safety [9]. From surgery outcomes [10] to maternal mortality rates [11] and for medical students [12], residents [13], surgeons [14], and nurses [15], race plays a role in adverse health outcomes.

About half of Indigenous people say that they experience racism very often [16]. In the medical setting in particular, Indigenous people are 2.6 times more likely to report racially based maltreatment [17] and are 10 times more likely to experience discrimination compared to non-Hispanic White patients [18]. A recent study that gathered experiences of Indigenous patients reported a variety of adverse experiences [8]. These patients often felt that they were experiencing bias, treated poorly, threatened, and dismissed. They felt that their medical problems were trivialized; that they were treated unkindly, especially in discussions regarding pain; and that these experiences led to worsened care. Racism is related to health disparities in the area of mental health, cancer, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and even adverse birth outcomes [19,20,21].

The Institute of Medicine (IOM), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) have all discussed the importance of providers and healthcare organizations providing culturally competent and equitable care [22,23,24]. Lack of attention to cultural factors in the clinic is related to a number of negative outcomes, including non-adherence, unnecessary visits and tests, and longer hospital stays [6]. Further, almost half of all providers (44%) say that addressing culture in clinic settings is “somewhat to extremely stressful,” [25] indicating a poor level of confidence and competence in the area that requires further training. However, there is evidence that training healthcare professionals about cultural issues can be effective in increasing knowledge on the topic [1] and improving health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority patients [26,27,28]. In a notable example, after providers at Massachusetts General Hospital received online cross-cultural training, the proportion of African-American patients who felt they received a lower quality of care than most White, English-speaking patients decreased from 25% in 2004 to 7% in 2012 [29].

While effective methods to improve cultural competency of healthcare providers exist, many challenges remain in delivery and effectiveness. Less than half of all fourth-year medical students demonstrate competency during common cross-cultural situations; the majority feel unskilled in providing basic cross-cultural care [30]. One partially successful medical-student training program aiming to prepare them for cross-cultural healthcare found improvements in assessment skills, collaboration with an interpreter, and level of preparedness in working with ethnic and cultural minority patients. However, the training did not change how students work with patients who use complementary and alternative medicine, have non-Western medicine health beliefs, distrust the medical system, are transgender patients, are religious minorities (including an inability to identify how religious beliefs affect clinical care and treatment), or are new immigrants [26]. Clearly some content and skills around cultural learning are more effectively acquired than others, demonstrating considerable room for improvement about how to teach this material effectively. Training carried out in classrooms, discussion groups, or with online learning methods might not be sufficient. Also, it is difficult to create and maintain a program around cultural effectiveness in a medical school despite the critical need for such programs [31]. In a review of five programs that implemented cultural competency curricula during residency, only 3 remain today [32]. However, even very little effort can increase learning in the area of cultural effectiveness and social justice. For example, two students at the John A. Burns School of Medicine at University of Hawaii at Manoa in the USA created and evaluated a program that taught medical students about social justice using online discussion groups and social media. They discovered that 92% of students increased knowledge of social justice [33]. This may be the first program that has successfully improved students’ social justice beliefs and has disseminated this information.

The Society for General Internal Medicine Health Disparities Task Force recommends three critical components for training in racial and cultural health disparities. It is important to address: (1) attitudes such as unconscious bias, stereotyping, and mistrust; (2) knowledge and history of health disparities using a social determinants of health lens; and (3) skills to effectively communicate, assess, and treat across cultures [1]. These components are important because, unfortunately, unconscious bias concerning patients’ race and social class plays a role in health professionals’ (including residents, surgeons, and nurses) decision-making [13]. Even providers who are aware of the social determinants of health rate patients’ health outcomes as being 90% attributable to patient factors, and over 40% did not believe there was strong evidence of the role of race in health outcomes [34]. Unconscious bias coupled with inaccurate beliefs of the cause of health outcomes for patients is magnified for Indigenous patients who experience prevalent stereotyping and bias within the healthcare system. Therefore, training that starts with basic information about the history of local communities, their political status, and cultural beliefs can help to reduce the perpetuation of false stereotypes that may contribute to unequal care.

The purpose of this project was to evaluate whether medical students who had received an Indigenous health lecture series at a single USA medical school had improved learning at the completion of the program and 6 months after the training. The hypothesis was that training would have a positive effect on students’ learning in the areas of knowledge, social justice, cultural empathy, cultural intelligence, and cultural humility at the completion of the program and at the follow-up period.

The Intervention

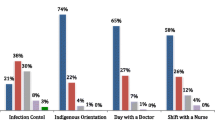

First-year medical students in 2014 (year 1) and in 2015 (year 2) received 7 h of coordinated lectures over 1 to 2 weeks about Indigenous peoples’ history, culture, and health [35]. The majority of students (year 1 = 96.66%; year 2 = 88.33%) attended these lectures, as they are part of their core curriculum, yet attendance is not taken, and therefore, the courses are not mandatory. This content was delivered mainly by Indigenous faculty from the School of Medicine, American Indian Studies and Education. There were slight differences in the curriculum from year 1 to year 2 given faculty availability and updates that were made based on feedback from the faculty and students (see Appendix Table 4).

Method

To evaluate the program, a one-group (non-randomized), pre-post-test quasi-experimental design was implemented. Students completed online questionnaires three times: 1 week before the lectures (pre-test), 2 weeks after the end of the lectures (post-test), and 6 months after the lectures (follow-up). However, in the year 1 post-test evaluation, four measures (standardized Social Justice Scale, Scale of Ethnocultural Empathy, Cultural Intelligence Scale, and Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure) of the five total measures proved unavailable due to technical errors in the survey software, which prevented retrieving the data for analysis. The pre-test also requested demographic information, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and current residence via zip code.

Instruments

Indigenous Knowledge and Beliefs

To measure the content learning of participants, the author created the Indigenous knowledge and beliefs (IKB) scale. This scale was adapted from a lesson plan assessment developed by anti-racism educators at the University of Calgary [36], and the content was tailored to focus on the Indigenous people local to the region (see Appendix Table 5). The scale consists of ten short-answer items such as “Currently, how many federally recognized American Indian nations are there in Minnesota?” or “What was the main goal of the boarding school era?” Respondents could attempt to answer the question or select “I don’t know.” This measure has two summary scores: the Indigenous knowledge and beliefs summary score and the Indigenous knowledge and beliefs attempts summary score. For the Indigenous knowledge and beliefs summary score, possible individual item scores ranged from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating an incorrect answer and 1 indicating a correct answer. The 10 items were averaged to create an IKB summary score with higher scores indicating a higher knowledge of both local and broad Indigenous knowledge and more culturally appropriate beliefs.

In order to account for self-efficacy on the lecture topics, a calculated attempt (i.e., those individuals who responded anything other than “I don’t know”) score called the Indigenous knowledge and beliefs attempts summary score was also created using the average number of “attempts” whether they answered the question correctly or not. Individual item scores ranged from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no attempt and 1 indicating an attempt.

Social Justice

The standardized Social Justice Scale (SJS) was used to capture medical student’s opinions about social justice (e.g., I feel confident in my ability to talk to others about social injustices and the impact of social conditions on health and well-being; I believe that it is important to respect and appreciate people’s diverse social identities) [36, 37]. This scale was designed to measure social justice–related values, attitudes, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and intentions based on a 4-factor conception of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Confirmatory factor analysis and analyses for reliability and validity were used to test the properties of the original scale. Internal consistency was good for all four subscales: attitudes (α = .95), subjective norms (α = .82), perceived behavioral control (α = .84), and intentions (α = .88). The original measure was shortened from 29 items down to 17, which included the original 4 subscales (see Appendix Table 6).

Ethnocultural Empathy

Students were asked to answer 16 questions (e.g., I share the anger of those who face injustice because of their racial and ethnic backgrounds) from the Scale of Ethnocultural Empathy (ECE) that includes 4 scales: empathic feeling and expression, empathic perspective taking, acceptance of cultural differences, and empathic awareness [38]. This scale was shortened from 31 to 16 questions for relevancy and brevity (see Appendix Table 7). High internal consistency and test–retest reliability estimates of the original scale have been demonstrated [38].

Cultural Intelligence–Specified Indigenous Culture

Students were asked 10 items (out of 20 questions from the original measure; see Appendix Table 8) from a standardized scale examining cultural intelligence–specified for Indigenous culture (Cultural Intelligence Scale (CIS)) [39]. Items were on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = disagree strongly” to “7 = agree strongly” (e.g., I check the accuracy of my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from Indigenous cultures; I know the legal systems of Indigenous cultures). The original measure has demonstrated good reliability (α = .70–.86) and significant convergent and discriminant validity [39].

Multicultural Ethnic Identity

Students were asked to answer the 16-question Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) [40]. Twelve items use a 4-point Likert scale (“1 = strongly agree” to “4 = strongly disagree”; e.g., I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group), and 4 items are open-ended and ask about cultural identity of self and of parents (e.g., my father’s ethnicity is?). Studies have demonstrated good reliability for both high school (α = .81) and college samples (α = .90) [40].

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were examined for all student characteristics including age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Additionally, paired t tests were conducted to examine changes in student responses between pre, post, and follow-up surveys for all study measures (i.e., Indigenous knowledge and beliefs, cultural intelligence–specified Indigenous knowledge, multicultural ethnicity identity, social justice, and ethnocultural empathy) with the exception noted above of missing data for four measures for the 2014 cohort post-test. Surveys for the three time points were linked using demographic information (birth date, zip code, gender), and a participant identification number was created. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Year 1

In year 1, there were a total of 60 students and 58 students (97%) filled out pre-lecture surveys; however, the number of participants that was used in the analysis is reduced given that the participants needed to have completed a survey in at least one other time period as is customary with paired t tests (see Table 2). Approximately half (55%) were male, 91% were White, and the mean age was 25.2 years (SD = 2.8); see Table 1. As shown in Table 2, students’ IKB summary scores increased significantly between pre- and post-lecture surveys (mean difference = 0.35, p < .0001) and between pre and follow-up (mean difference = 0.22, p < .0001). Student’s IKB summary scores, however, decreased significantly between post and follow-up (mean difference = − 0.09, p = .02). Student’s IKB summary attempt scores increased significantly between pre- and post-lecture surveys (mean difference = 0.42, p < .0001) and between pre and follow-up (mean difference = 0.36, p < .0001), but no differences were noted between post and follow-up (p = .69). Although student’s empathy, intelligence, and identity scores increased between pre and follow-up lecture, none were found to be statistically significant. Similarly, social justice scores decreased slightly between pre and follow-up, but the difference was non-significant.

Year 2

In year 2, there were a total of 60 students, of which 53 students (88%) filled out pre-lecture surveys and fewer represented in the analysis (see Table 3). Slightly less than half (45%) of the students were male, 81% were White, and the mean age was 23.8 years (SD = 1.8); see Table 1. Similar to year 1, student’s IKB summary scores at year 2 (Table 3) increased significantly between pre- and post-lecture surveys (mean difference = 0.15, p < .0001) and between pre and follow-up (mean difference = 0.09, p < .001). The decrease in IKB summary scores between post and follow-up was not significant (p = .11). Students’ IKB summary attempt scores at year 2 also increased significantly between pre- and post-lecture surveys (mean difference = 0.34, p < .0001) and between pre and follow-up (mean difference = 0.21, p < .0001). A significant decrease between student’s post and follow-up IKB summary attempt scores was noted (p = .02).

Student’s empathy (ECE) scores at year 2 (Table 3) increased significantly between pre- and post-lecture surveys (mean difference = 0.24, p < .0001) but not between pre and follow-up (mean difference = 0.01, p = .88), whereas post-ECE scores were significantly higher than follow-up ECE scores (mean difference = 0.17, p = .03). Student intelligence (CIS) post and follow-up scores were significantly higher than pre-lecture scores (pre-post mean difference = 1.02, pre-follow-up mean difference = 0.46, p < .001), while post-CIS scores were significantly higher than follow-up CIS scores (mean difference = 0.50, p < .0001). No significant differences were noted in student’ social justice and identity scores between pre, post, or follow-up lecture surveys.

Discussion

This project tested the effects of adding seven didactic hours to a first-year medical school curriculum mostly delivered by Indigenous faculty. The curriculum was nested in a university with a mission of American Indian Health and a Center for American Indian Minority Health, which houses the American Indian medical student recruitment core.

Our results suggest that Indigenous health lectures have lasting effects on students’ knowledge up to at least 6 months. Knowledge is the first component in most models of cultural effectiveness, dexterity, and humility. In fact, three recommendations to address structural racism in medicine include the following: “First, learn about, understand, and accept the United States’ racist roots. Second, understand how racism has shaped our narrative about disparities. Third, define and name racism [41].” Similarly, in an international consensus statement around medical education, colonization, racism, and privilege were named as the strongest barriers to Indigenous health [42]. Authors expressed the importance of decolonizing western medical education through changes in the medical infrastructure led by Indigenous people.

The study intervention, however, had less strong of an effect on students’ growth in other domains. For instance, cultural intelligence was approaching significance in year 1 from pre-test to follow-up (mean difference = 0.23, p = .06) and was significant in year 2 from pre-test to follow-up (mean difference = 0.46, p = .006), indicating that there was a trend of improvement in this measure. While student’s ethnocultural empathy (ECE) scores at year 1 did not reach a level of significance, in year 2 (Table 2), ECE increased significantly between pre- and post-lecture surveys (mean difference = 0.24, p < .0001) but not between pre and follow-up (mean difference = 0.01, p = .88); see Table 3. Although there were improved effects, possibly due to updated content in the second year, the intervention did not have long-lasting effects on student’s empathy. This is interesting because students continued to maintain their knowledge about Indigenous people, which, one would think, would affect beliefs and, therefore, empathy, yet it did not in the long term. It is possible that although one learns and continues to retain the information, the effect of actively learning and discussing the topic affects empathy, but not in isolation and not over time. It is also possible that the dose was insufficient for lasting effects, which requires more testing.

Other programs that have been successful at improving the knowledge, skills, and beliefs of students around Indigenous health have added additional components besides didactic learning including experiential learning opportunities. For instance, the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences Northwest campus created an interdisciplinary program to address health disparities with a focus on Marshallese patient populations [43]. This program was comprised of two didactic lectures co-created by a Native Marshallese physician, an experiential component within the clinic, and a service learning project within the community. Students who participated in this program reported significantly improved cultural competence and readiness for interpersonal learning, in addition to improved knowledge, skills, and behaviors towards working with Marshallese patients. At the John A. Burns School of Medicine, Native Hawaiian specific cultural competence training began in 2003 and now electives include a Dean’s certificate in Hawaiian Native Health as well as the Kalaupapa service learning project [44,45,46]. Evaluations of this program indicated that over 95% of medical students in the Native Hawaiian health elective either agreed or strongly agreed that they have a better understanding of tools that can be used for Native Hawaiian people to heal from cultural trauma. Students also reported that they learned about Indigenous perspectives and beliefs and it reinforced their commitment to rural and underserved areas [45]. It appears that experiential learning opportunities, whether in clinic or in community, provide a boost to the effects of teaching didactic content resulting in improved readiness and skills to work with Indigenous patients.

In the case of social justice beliefs and cultural humility in this study, neither was significantly improved at post-test or follow-up. These domains appear more difficult to change than knowledge and skills. However few, there are programs that have had success in teaching social justice, which may provide strategic examples for other developing medical curriculums. In particular, at the University of Otago in New Zealand, a study was conducted to assess social accountability within Indigenous medical education. Social accountability is a similar concept to social justice. Stakeholders including students, teachers, and community members were interviewed about how this Indigenous curriculum created social accountability to address Indigenous health disparities. They reported that they believed that the following components of the curriculum created social accountability for health professionals: (1) advocacy for Māori health in the community, university, and clinics; (2) putting social engagement into practice; and (3) creating a transformative practice around advocating for Māori health [47]. The University of Otago puts social accountability into practice through its commitment to address Māori health disparities mandated through the Treaty of Waitangi, using a strategic plan to recruit Māori students and teaching students more Indigenous health content than any other university in the world [48]. Through qualitative interviews, researchers discovered that this Indigenous health curriculum taught students how to advocate for patients and become change agents to reduce Indigenous health disparities. In other words, this curriculum has resulted in improved social justice beliefs and actions of students. In this case, a government decree, recruitment efforts, and a larger quantity of hours taught about Indigenous health resulted in improvements in social justice beliefs.

Although not Indigenous focused, a preclinical social justice program at Mount Sinai requires “a didactic course, faculty and student mentorship, research projects in social justice, longitudinal policy and advocacy service projects, and a career seminar series [49].” Students were interviewed in regard to their learning from this program, and the most common theme was that students were able to apply their learning about health disparities and social determinants of health to clinical encounters. This is an important outcome and highlights the need to teach social justice in a variety of ways (e.g., didactic, research project, and service project) with mentorship for both students and faculty.

In searching for best practices to improve social justice, an area that did not see improvement in our study, it is important to look to other programs that have had long-standing missions around social justice to guide future projects given the lack of evaluation research in this area. In particular, at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, core competencies in medical social justice cover knowledge, skills, and beliefs regarding social determinants of health, health justice advocacy, and community needs [50]. The purpose of this social justice program is to implement a student-driven curriculum to expose learners to various components of social justice in health and medicine by using their own inputs for content and design [51]. At the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, a social justice expert group convened that led to curriculum revision and improved student competencies in social justice [52]. The addition of student-led curriculum and social justice competencies creates a bar for all students to meet and also requires more faculty to put social justice content into their lectures [53] which may prove to increase the social justice competency of students.

Limitations

The purpose of the research project was to test the learning of medical students before and after they received a series of seven lectures. No other program in the USA has implemented Indigenous health content within the core curriculum for all students and tested it. Therefore, the first goal of this investigation was to determine if the training was feasible and to test the hypothesis that training has a positive effect on students’ learning in the areas of knowledge, social justice, cultural empathy, cultural intelligence, and cultural humility. A one-group (non-randomized), pre-post-test was implemented using a quasi-experimental design and a convenience sample of first-year medical students. The author recognizes that with this design, there are substantial threats to both internal and external validity given the selection of participants and the lack of control groups and randomization. Measures were condensed in this study to reduce respondent fatigue. Due to modifications to some of the measures, it is possible that the reliability and consistency of these measures were not maintained. Further, while our team tried to make improvements to the lecture during year 2, small differences to the intervention exist and therefore cohorts 1 and 2 did not receive the exactly the same intervention. A power analysis was not completed before the data was analyzed. Given this limitation, some of the analyses may have lacked power possibly explaining some of the null results.

This intervention included a lecture series created by local stakeholders and was tailored to represent tribes of the region and may not be representative to other communities and tribes. For instance, stakeholders were very outspoken about the needs of the local Indigenous community and what they wanted their healthcare professionals to know about them, which may not be the case in all other communities. It is important to note with over 570 tribes in the USA alone, one must not generalize and assume similarities exist between them.

Implications

There are many barriers for effective healthcare for Indigenous people. Without a medical provider who knows about your culture and health beliefs available at your local clinic, or an administrator that advocates for your community, healthcare is unlikely to effectively service Indigenous patients in that community. According to the AAMC, in 2015, only 0.2% of US medical school (not including osteopathic medicine programs) applicants were Indigenous, only 21 of 19,553 US medical student graduates in 2017 were Indigenous, only 0.6% are active physicians, and only 0.5% are full-time faculty [54]. Further, Indigenous representation in medical education has decreased, not increased, in the USA over the last several years and there are very few Indigenous faculty in medical schools (0.1%) or in the sciences [55]. Fewer underrepresented potential faculty are being hired as assistant professors when compared to those from well-represented groups, and simulation models suggest that this inequity will not change for the next 60 years at least [56]. Therefore, more needs to be done to include Indigenous students and faculty in the medical field. Content important to underrepresented groups should be reflected in the curriculum; however, this cannot be done without Indigenous advocates and allies.

Future Directions

The solution to addressing Indigenous health disparities is multifaceted and requires intervention at multiple points. Intentionality is important. Programs that set out to teach values and beliefs around patient-centeredness and social justice advocacy have succeeded in reaching these goals [57]. For example, to improve social justice beliefs and behaviors, successful programs create core competencies and train faculty. Further, medical school initiatives and missions focused around underserved populations increase the number of providers practicing in those areas [58]. It is important to be intentional and strategic about the goal of addressing health disparities and also address the root of the problem. For deep structural changes to happen with regard to Indigeneity, decolonizing approaches could address rebalancing of systems of hierarchy in educational systems, critically analyzing the role of colonization in medicine and healthcare, and addressing root causes of disparate outcomes like racism and inequity. Although the Indigenous curriculum in this study resulted in some positive learning outcomes, future projects will work to be more holistic in nature including engaging more Indigenous medical education experts, more patient voices, and more administrative collaboration, as well as work to create learning objectives, core competencies, and a variety of and an increased amount of learning opportunities such as mentoring, service learning, and student-led initiatives.

Conclusion

Culturally appropriate care in the USA is critical to the improved health of Indigenous people and requires a trained health workforce. This study found that medical student knowledge could be persistently increased by a lecture series, but other key values were less strongly affected. Future work should aim to discover what types of interventions (e.g., didactic vs. experiential), what amount, and at what intervals of training will produce significant improvements in healthcare providers’ knowledge, beliefs, and skills. At this intersection of health justice and education justice, Indigenous health content is critical; it is especially important for programs located on or near communities with higher rates of Indigenous patients who can work to reduce health disparities directly.

Notes

In this manuscript, the term Indigenous refers to Native people worldwide. Other commonly employed terms for Indigenous people in North America have included American Indian, Native American, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and First Nations. The word Indigenous will be capitalized in this manuscript to indicate that this group is distinct from other racial and ethnic groups and sovereign nations. Although not always possible within this manuscript, it is important to use local and tribal language when referring to specific tribes whenever possible.

Abbreviations

- AAMC:

-

Association of American Medical Colleges

- CIS:

-

Cultural Intelligence Scale

- ECE:

-

Scale of Ethnocultural Empathy

- IKB:

-

Indigenous knowledge and beliefs

- IOM:

-

Institute of Medicine

- MEIM:

-

Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- SJS:

-

Social Justice Scale

References

Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, Bussey-Jones J, Stone VE, Phillips CO, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–65.

Lewis ME, Myhra LL. Integrated care with Indigenous populations: considering the role of health care systems in health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29:1083–107.

Hasnain-Wynia R, Kang R, Landrum MB, Vogeli C, Baker DW, Weissman JS. Racial and ethnic disparities within and between hospitals for inpatient quality of care: an examination of patient-level hospital quality Alliance measures. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):629–48.

Commonwealth Fund. A review of the quality of health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Commonwealth Fund. 2004. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2004/sep/review-quality-health-care-american-indians-and-alaska-natives. Accessed Oct 5 2017.

Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. 2004. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30262.x, 19, 101, 110.

Nelson AR, Stith AY, Smedley BD. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003.

Puumala SE, Burgess KM, Kharbanda AB, Zook HG, Castille DM, Pickner WJ, et al. The role of bias by emergency department providers in care for American Indian children. Med Care. 2016;54(6):562–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000533.

Goodman A, Fleming K, Markwick N, Morrison T, Lagimodiere L, Kerr T. “They treated me like crap and I know it was because I was Native”: the healthcare experiences of Aboriginal peoples living in Vancouver's inner city. Soc Sci Med. 2017;178:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.053.

Walker R, St Pierre-Hansen N, Cromarty H, Kelly L, Minty B. Measuring cross-cultural patient safety: identifying barriers and developing performance indicators. Healthcare Quarterly (Toronto, Ont). 2010;13(1):64–71.

Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):996–1002.

Louis JM, Menard MK, Gee RE. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):690–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000704.

Haider AH, Efron DT, Swoboda S, Villegas CV, Haut ER, Bonds M, et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students. JAMA. 2011;306(9):942–51. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1248.

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, Dossick DS, Scott VK, Swoboda SM, et al. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(5):457–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4038.

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, Dossick DS, Scott VK, Swoboda SM, et al. Unconscious race and class bias: its association with decision making by trauma and acute care surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3):409–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000392.

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, Scott VK, Swoboda SM, Zogg CK, et al. Unconscious race and class biases among registered nurses: vignette-based study using implicit association testing. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:1077–86.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.01.065.

Yamashiro A, Goodyear-Ka'opua N. Achieving social and health equity in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press; 2014. p. 254.

Larson A, Gillies M, Howard PJ, Coffin J. It's enough to make you sick: the impact of racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;4:322.

Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, Waldegrave K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in New Zealand: cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2006;367:2005–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68890-9.

Kaholokula JK, Iwane MK, Nacapoy AH. Effects of perceived racism and acculturation on hypertension in Native Hawaiians. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69(5 Suppl 2):11–5.

Kaholokula JKA. Racism and physical health disparities. In: Alvarez AN, CTH L, Neville HA, editors. The cost of racism for people of color: contextualizing experiences of discrimination. Cultural, racial, and ethnic psychology book series. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2016. p. 163–88.

Kaholokula JKA, Antonio MCK, Ing CKT, Hermosura A, Hall KE, Knight R, et al. The effects of perceived racism on psychological distress mediated by venting and disengagement coping in Native Hawaiians. BMC Psychology. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-017-0171-6.

Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Cultural competence education. 2005. https://www.aamc.org/download/54338/data/culturalcomped.pdf. Accessed Oct 15 2017.

Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler WW, George SM, Elwood WN. The cultural framework for health: an integrative approach for research and program design and evaluation. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; 2015.

De Souza IET, editor. Intercultural mediation in healthcare: myths and facts. Cross Cultural Health Conference; 2017 February 17, 2017; Honolulu, Hawaii.

Weissman JS, Betancourt J, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kim M, Clarridge B, et al. Resident physicians' preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(9):1058–67.

Massachusets General Hospital, Center for Diversity and Inclusion. Cross-cultural education. 2017. http://www.massgeneral.org/mao/multiculturaled/. Accessed Oct 15 2017.

Watt K, Abbott P, Reath J. Developing cultural competence in general practitioners: an integrative review of the literature. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0560-6.

Betancourt JR, editor. Cross-cultural training for health professionals. Cross Cultural Health Conference; 2017 February 17, 2017; Honolulu, Hawaii.

Green AR, Chun MBJ, Cervantes MC, Nudel JD, Duong JV, Krupat E, et al. Measuring medical students’ preparedness and skills to provide cross-cultural care. Health Equity. 2017;1:15–22.

Chun MBJ, Takanishi DM Jr. The need for a standardized evaluation method to assess efficacy of cultural competence initiatives in medical education and residency programs. Hawaii Med J. 2009;68(1):2–6.

Shah SS, Sapigao FB, Chun MBJ. An overview of cultural competency curricula in ACGME-accredited general surgery residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(1):16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.06.017.

Porter T, Jones E, editors. Student engagement with health disparities through Facebook and video chat. Cross Cultural Health Conference; 2017 February 17, 2017; Honolulu, Hawaii.

Britton BV, Nagarajan N, Zogg CK, Selvarajah S, Schupper AJ, Kironji AG, et al. Awareness of racial/ethnic disparities in surgical outcomes and care: factors affecting acknowledgment and action. Am J Surg. 2016;212(1):102–8.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.022.

Lewis M, Prunuske A. The development of an Indigenous health curriculum for medical students. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):641–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001482.

Chagnon-Greyeyes C, Johnston B, Kelly J, Paquette D, Srivastava A, Wong T. Indigenous knowledge handout. CARED Collective, Calgary. 2015. http://www.ucalgary.ca/cared/indigenousknowledgehandout. Accessed Mar 13 2019.

Torres-Harding SR, Siers B, Olson BD. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Social Justice Scale (SJS). Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(1–2):77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9478-2.

Wang Y-W, Davidson MM, Yakushko OF, Savoy HB, Tan JA, Bleier JK. The Scale of Ethnocultural Empathy: development, validation, and reliability. J Couns Psychol. 2003;50(2):221–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.221.

Ang S, Dyne L, Koh C. Development and validation of the CQS. Routledge; 2008.

Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: a new scale for use with diverse groups. J Adolesc Res. 1992;7(2):156–76.

Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting black lives - the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1609535.

Jones, R., Crowshoe, L., Reid, P., Calam, B., Curtis, E., Green, M., ... & Milroy, J. (2019). Educating for indigenous health equity: an international consensus statement. Acad Med, 94(4): 512–519.

McElfish PA, Moore R, Long CR, Purvis RS, Rowland B, Buron B, et al. Integrating interprofessional education and cultural competency training to address health disparities. Teach Learn Med. 2017;30:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2017.1365717.

Gaddis C, editor. The dean’s certificate in Native Hawaiian Health. Cross Cultural Health Conference; 2017; Honolulu, Hawaii.

Lee WK, Harris CCD, Mortensen KA, Long LM, Sugimoto-Matsuda J. Enhancing student perspectives of humanism in medicine: reflections from the Kalaupapa service learning project. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0664-7.

Carpenter D-AL, Kamaka ML, Kaulukukui CM. An innovative approach to developing a cultural competency curriculum; efforts at the John A. Burns School of Medicine, Department of Native Hawaiian Health. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(11 Suppl 2):15–9.

Pitama, S., Beckert, L., Huria, T., Palmer, S., Melbourne-Wilcox, M., Patu, M., … & Wilkinson, T. J. (2019). The role of social accountable medical education in addressing health inequity in Aotearoa New Zealand. J R Soc New Zealand, 1–14

Pitama S. (2013) “As natural as learning pathology” the design, implementation and impact of indigenous health curricula within medical schools. Doctoral dissertation. University of Otago.

Bakshi S, James A, Hennelly MO, Karani R, Jakubowski A, Ciccariello C, et al. The Human Rights and Social Justice Scholars Program: a collaborative model for preclinical training in social medicine. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81(2):290–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2015.04.001.

Schiff T, Rieth K. Projects in medical education: “Social Justice in Medicine” a rationale for an elective program as part of the medical education curriculum at John A. Burns School of Medicine. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2012;71(4 Suppl 1):64–7.

Ambrose AJ, Andaya JM, Yamada S, Maskarinec GG. Social justice in medical education: strengths and challenges of a student-driven social justice curriculum. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014;73(8):244–50.

Coria A, McKelvey TG, Charlton P, Woodworth M, Lahey T. The design of a medical school social justice curriculum. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1442–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a325be.

Hixon AL, Yamada S, Farmer PE, Maskarinec GG. Social justice: the heart of medical education. Soc Med. 2013;7(3):161.

American Association of Medical Colleges. Total U.S. medical school graduates by race/ethnicity and sex, 2013-2014 through 2017-2018. 2018. https://www.aamc.org/download/321536/data/factstableb4.pdf. Accessed Oct 15, 2019

American Association of Medical Colleges. Distribution of U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity. 2016. https://www.aamc.org/download/475556/data/16table8.pdf. Accessed Oct 15 2017

Gibbs KD, Basson J, Xierali IM, Broniatowski DA. Decoupling of the minority PhD talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the US. eLife. 2016;5. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.21393.

Cha SS, Ross JS, Lurie P, Sacajiu G. Description of a research-based health activism curriculum for medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1325–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00608.x.

Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804–11. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jamie Smith, Solomon Trimble, David Mehr, Robin Kruse, and Melissa Walls for their assistance with this manuscript. I would also like to acknowledge all of the contributors to this curriculum and the students who participated in the lectures and the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Publish

This study was evaluated by the University of Minnesota and the University of Missouri and was determined not to meet the criteria for human subjects research given its focus on curriculum evaluation. Therefore, a need for consent was waived by the IRBs.

Informed Consent

All participants completed an informed consent in order to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis, M.E. The Effects of an Indigenous Health Curriculum for Medical Students. Med.Sci.Educ. 30, 891–903 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00971-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00971-8