Abstract

Objective

Effectively managing patient distress in oncology is challenging. Trainees in oncology experience distress along with their patients and patients’ families, especially during an inpatient admission. This study evaluated the physician-in-training experience while working on an inpatient hematology-oncology ward.

Methods

We collected a survey from internal medicine interns and residents at the end of a 2- or 4-week-long rotation on a hematology-oncology ward. It included the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R), a measure of distress, information about resident demography, rotation experiences with death, and personal circumstances that could affect distress levels. House officers were asked to provide comments regarding their most stressful experiences or how they were affected by dying patients.

Results

Fifty-six residents completed questionnaires (58 % overall response rate) and scored IES-R 18.7 (SD 14.2) indicating that the majority (80 %) experienced significant clinical distress (IES-R ≥8) and 20 % experienced posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) levels of distress (IES-R ≥33). Comment themes are highlighted and included general frustration and death-related events. Forty-one (73 %) reported that their IES-R event was a death-related experience, and 39 (69.6 %) reported that attending to dying patients was the most stressful part of the rotation. Residents cared for 4.28 patients at the end of life on average during the rotation, and 68 % derived a sense of meaning from such work.

Conclusions

This study suggests that physician-trainee distress is significantly elevated while working on a hematology-oncology ward and may relate to general frustration and death-related events. Further study should evaluate the etiology of medical trainee distress in oncology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

It is apparent that physicians, particularly those in training, have great difficulty in maintaining their equanimity when they must care for and relate intimately to terminal dying patients.

-Kenneth L. Artiss M.D., N Engl J Med 1973

Introduction/Background

Just as cancer patients and their families experience distress over cancer, trainees in oncology also experience distress, particularly early in their professional experience [1]. It is not possible to make our patients better without understanding them; it is not possible to make ourselves more humanistic physicians without understanding how patient-care experiences shape us.

For the medical trainee, the inpatient oncology rotation is a highly stressful experience, in part because of its proximity to dying patients and exposure to challenging family interactions that produce high levels of distress [2]. Interns and residents are often the frontline of medical personnel who manage many difficult situations within a hospital setting. Death-related distress, usually in the form of secondary traumatic stress, has been documented among oncology physician trainees and in 16 to 34 % of oncologic nurses [3–5]. Chronic conditions such as burnout, depression, and low quality of life (QOL) are highly correlated and prevalent among both medical students and physician trainees at rates higher than the general population [5–8]. These conditions are associated with an increased risk of medical and medication errors [5], unprofessional behavior [8], jeopardized patient safety [7], and decreased patient satisfaction [6] with medical care. Although burnout, depression, and low QOL have been previously described in residents as a consequence of year-long training, distress, as an acute reaction to a specific training-related stressor, has not been extensively evaluated. While intrinsic to the training environment of the hematology-oncology ward, death-related vicarious trauma may be associated with distress for the young trainee. Distress has been associated with burnout, less career satisfaction, and less patient satisfaction [6–9].

Acute physician-trainee distress has not been widely explored in selective clinical settings, such as inpatient hematology-oncology. Therefore, this study also offers an exploratory analysis of distress in relation to patient death events, personal stressors, and derived sense of meaning, which could represent a protective mechanism to counter distress.

Methods and Materials

Participants

Subjects were internal medicine house officers (i.e., interns and residents) working on a single-institution hematology-oncology ward rotation. House officers who rotated a second time during the course of the study were not included. Preliminary and categorical internal medicine interns were both included.

Procedure

In September 2013, a single-institution institutional review board approved this study. House officers who met the inclusion criteria were consented and asked to fill out the survey 3 days prior to finishing the rotation. Surveys were collected at that time and up to 2 days after finishing the rotation. The survey was administered in paper form or via RedCAP® and consisted of the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R), demographic information (age, gender, postgraduate year, previous hematology-oncology rotations, length of this rotation, absences), clinical information about the rotation and death-related events (1) “was the stressful event (the IES-R asks the participant to identify a stressful event) death-related?” (Yes/No) (2) “How many ‘actively’ dying patients did you care for during your rotation?” (3) “Were these the most stressful experiences of your rotation?” (Yes/No) (4) “If no, briefly describe the most stressful issue you’ve been facing during this rotation” (free-text). (5) “Did you derive a sense of meaning from working with dying patients?” (Yes/No) (6) “Please describe how dealing with dying patients on this rotation has affected you” (free-text), and personal situational information (e.g., personal stress, effect on personal/work life, verbal mistreatment on the wards by attending physicians, family support).

Measures

The IES-R is a 22-item scale to measure current subjective distress related to a specific event that the participant is asked to identify [10, 11]. It highlights the three most commonly reported responses to traumatic stressors, avoidance (8 questions), intrusion (7 questions), and hyperarousal (7 questions). It has proven validity in multiple settings with averaged internal consistencies of 0.86 and 0.90 for intrusive and avoidance subscales, respectively [12–15]. There is a theoretical maximum of 88 points, and scores above an 8 are considered to have clinical implications while scores under 8 are subclinical. Scores over 33 represent a high likelihood (over 90 %) of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [16, 17]. Of note, a clinical interview is necessary to make any formal psychiatric diagnosis, and therefore, a scale may only suggest its presence based on studies that have included both the scale (e.g., IES-R) and formal psychiatric evaluations.

Statistical Analysis

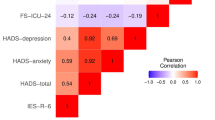

The analysis of this study involved primarily descriptive statistics. This included means, standard deviations, medians, and ranges, or percentages of several demographic variables and the scores of the scales. Univariate linear regression was performed on continuous variables, and non-parametric correlations were made using Spearman’s Rho. Statistical procedures were performed using the SPSS version 22 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, 2013), and statistical tests were two tailed with a 5 % significance level.

Results

Fifty-six out of 96 residents completed the questionnaires (58 % overall response rate). The cohort was comprised of 33 internal medicine interns (PGY I) (59 %) followed by 13 third-year residents (PGY III) (22 %) and 10 second-year residents (PGY II) (19 %), with an average age of 28.78 (SD 2.3) ranging from 26 to 35 years old (Table 1). Thirty-nine house officers spent 2 weeks (70 %) and 17 house officers spent 4 weeks (30 %) on the rotation. One resident (1.8 %) was absent for over 3 days of his 2-week rotation. On the ward, 35.7 % had rotated previously (although not during the study period).

The cohort’s distress (IES-R) averaged 18.7 (SD 14.2), and subscale results were intrusion 8.1 (SD 6.1), avoidance 7.4 (SD 6.2), and hyperarousal 3.2 (SD 3.5) (Table 1). IES-R scores indicated that the majority (80 %) experienced significant distress (≥8), and 20 % experienced PTSD levels of distress (≥33). Intern (PGY I) IES-R was 20.09 (SD 13.04) and did not differ significantly from resident IES-R (PGY II/III) 17.22 (SD 17.18) (p = 0.618). Distress scores of house officers who rotated for 2 weeks (IES-R 19.02) did not differ significantly from those who rotated for 4 weeks (IES-R 19.11) (p = 0.974).

Forty-one participants (73 %) stated that their IES-R event was related to a death-related experience on the job. This question was followed up with an additional question where 39 participants (69.6 %) reported that attending to dying patients was the most stressful part of the rotation and 28 provided comments describing how dealing with dying patients had affected them on the rotation (Table 2). On average, residents reported caring for 4.28 dying patients (SD 3.6) with a range from 0 to 20 over the course of the rotation. Only one resident reported not taking care of at least one dying patient during his 2-week rotation (his IES-R score was 18.0). Seventeen participants (30.4 %) reported that it was not the most stressful experience, and all seventeen left comments describing what they considered to be the most stressful experience of the rotation (Table 2).

Table 2 lists house officer comments based on whether they felt that death-related experiences were the most stressful of the rotation (left-hand column) or not (right-hand column). The most common themes were death-related events and general frustration and were evenly divided between both groups/columns. House officers who felt that caring for dying patients was the most stressful experience of the rotation also commented on general frustrations of the rotations, and those who did not feel that death events were the most stressful also appeared to comment on death events. Two commentators gave personal reflections of how they actually felt, “terribly, with guilt” and “made me question my actions and whether I missed anything,” which were in the death-as-most stressful column. That column garnered more positive comments as well. The frustration theme appeared to center around interactions with educators, not having enough time to adequately care for patients, and disagreement about treatment plans. Many house officers offered what they felt should have been provided for patients or families but was not offered or provided. Many chose to cite examples instead of directly answering the question about how dealing with dying patients had affected them. Although, frequently, the descriptions of events provided insight into how they actually felt, such as “seeing so many dying patients was stressful,” “made me question,” “more comfortable,” and “overwhelming experience,” for example.

Despite the majority of negative comments about death and frustrations with the rotation, 68 % of house officers replied yes to the question “do you derive a sense of meaning from working with dying patients?” One resident commented, “I felt very fulfilled by this rotation and that what I did mattered. I was able to form relationships with a few patients as they stayed throughout my two weeks on service…It is tough to juggle it all but with a positive attitude and with time, you improve in all those domains.” These words seem to indicate a perspective that finds meaning in this work based on the relationships that are made. Another commented, “patients may not die if we do everything right,” which may indicate that this resident’s sense of meaning is tied to helping patients to obtain survival. However, identifying a derived sense of meaning and correlations with both death as the most stressful experience (r = −0.079, p = 0.543) or death-related IES-R events (r = −0.149, p = 0.251) were not statistically significant.

Personal stressors, as indicated by interns and residents, were concurrently experienced by 16 % of the cohort. Characteristics of house officers who identified personal stressors versus those who did not are listed in Table 3. Stressors included issues such as moving, marriages, family illnesses, financial losses, and breakups. The personal stressor group was slightly younger (27 versus 29) and had higher median IES-R scores (24.0 versus 18.9; average 18.0 versus 17.0) with similar subscale scores.

Discussion

The inpatient hematology-oncology ward engenders multiple stressful situations for medical house staff. Treating patients with end-stage diseases, interacting with patients’ family members who are often themselves experiencing distress, and simultaneously managing myriad acute medical conditions are difficult. The levels of distress documented by the IES-R in this study are similar to distress results for nurses who may have been exposed to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Taiwan (IES 17.8, SD 12.4) and are perhaps greater than obstetric professionals who experienced a miscarriage, for example [18, 19]. The rates of PTSD-like distress echo prevalence rates that are found among civilians in an area of a natural disaster (tsunami, earthquake) [20, 21]. This may be the first study to document IES-R scores for internal medicine residents rotating on a hematology-oncology ward.

The intern or resident rotating on a hematology-oncology ward may encounter death for the first time, and it is often without the team support that is frequently encountered in an intensive care unit. Dr. Artiss appreciated the unique stressors of the hematology-oncology ward environment [1] in 1973, and they continue today. While entrenched in this environment, residents (PGY II, III) are given new responsibilities at a higher level of care for their patients and are expected to endure a greater amount of stress during this rotation compared with others. They are also given increased responsibility for a select group of hematologic and oncologic patients, adding to uncertainty in making decisions about treatments.

This study highlighted common themes of frustration and death-related events that house officers rotating on an oncology ward may face. The theme of frustration with how care is delivered brings up a moral dilemma for residents who are obligated to carry out others orders. Additionally, death-related events appear to be highly salient for the interns and residents who are experiencing those events, albeit vicariously. The majority of house officers reported that their stress was related to a death event when asked in two different ways (two separate questions). Also, residents and interns who identified personal or non-work-related reasons for their distress reported slightly higher distress symptoms. Perhaps, the perception and experience of distress are cumulative; stressors mount as residents identified caring for a greater number of dying patients as well.

Concomitantly, the majority of house officers derived a sense of meaning from working with dying patients. Although the correlation was not statistically significant, perhaps finding meaning in clinical work ameliorates or modulates the stress of working with dying patients for some of the house officers. That is, a subgroup of house officers may seek meaning in their clinical work as a coping mechanism or therapeutic perspective. Several extrapolated comments, as listed in Table 2, could be seen as reflecting a need for meaning when it is absent (i.e., comments about frustration with providing futile care or care with which the resident may not have agreed). Many of the positive comments about the rotation reflected a sense of meaning “represents an opportunity to help during a time of greatest need.” These associations would require much further analysis to understand, especially since the survey did not allow for a universally understood definition of meaning. Without more qualifying data or a universally accepted understanding of meaning, it is not possible to draw strict conclusions from how house officers answered “do you derive a sense of meaning from working with dying patients?”

There are several important limitations to this study. It is a cross-sectional study involving a relatively small cohort without a control group, making its analysis descriptive and interpretations speculative. Perhaps, most limiting is that there is no baseline comparator data from other rotations, which could engender similar levels of distress; thus, it is difficult to draw any conclusion about the uniqueness of the hematology-oncology ward environment for the medical trainee. Also, the IES-R does not make a formal psychiatric diagnosis (as discussed in the “Methods and Materials” section), and it is not clear that the house officers actually were functionally impaired, which would be necessary for a PTSD diagnosis, despite experiencing relatively high IES-R scores. The number of end-of-life patients was subjectively obtained from each house officer and was subject to their retrospective perceptions of the rotation. Work hours would have been a helpful predictor of distress but were not collected. Although work hours are restricted to 80 h per week by ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education), there could still be an association with those who work close to or over 80 h per week but has not been a consistent predictor of burnout as recent studies with new work hour restrictions have indicated [22–24]. Finally, the overall response rate was 58 % for those residents who filled out both pre/postrotation surveys; it is quite plausible that the remaining 42 % of residents who did not fill out the surveys were even more distressed. Speculative reasons for not returning surveys may have included disgruntled attitudes and time pressure.

Interventions, in the form of group support, are effective in positively changing attitudes, improving an appreciation for the humanistic side of medicine in oncology, and improving provider confidence [25–27]. Also, many internal medicine programs currently have end-of-life, hospice, and palliative care training curricula [2, 28], and trainees have reported favorably on their implementation [29]. Simply having a psychological presence is a notable component in the clinical environment and may provide a catalyst to hone coping skills [30].

Few studies postulate a specific mechanism by which their intervention affects change. An underlying causal mechanism is rarely described in various intervention studies and needs to be investigated further. A deeper understanding of physician and trainee distress is necessary in order to promote improved provider quality of life and positive health outcomes for patients. Increasingly, physicians are expected to respond to patients empathically, but there is little formal guidance on how to do so within the distress-laden environment of oncology. It appears that the medical practitioner can easily vacillate between providing open, sensitive, and compassionate care to becoming overwhelmed, burnt out, and without proper education or mechanisms to emotionally take care of ones’ self. In order to best inform educational- and therapeutic-type interventions, a guiding theory is needed.

The theory of Conservation of Resources (COR) developed by Dr. Stevan Hopfoll approaches stress as inversely proportionate to one’s perceived losses [31, 32]. Similarly, a coping reserve model, as described by Dr. Laura Dunn [33], demonstrates how people manage stressors based on resources. These theories explain how house officers with personal stressors had slightly higher distress scores while caring for the same population of end-of-life patients. Also, these theories may explain why residents who reported personal stresses also reported caring for more dying patients as they saw a diminishing of their personal resources. Additionally, the majority of house officers derived meaning from attending to dying patients on the ward, even while they also reported high rates of distress. These theoretical guides are useful to develop directed strategies to develop and reinforce residents’ emotional resources. Heightened anxiety and the concurrent assignment of meaning suggest that the hematology-oncology ward environment is filled with teachable moments. Residents are most receptive to guidance in humanistic medicine when the events are most salient to them, as indicated by the adult learning theory [34]. This moment could also be seen as a critical teaching opportunity to ensure healthy coping techniques and the avoidance of maladaptive protective behaviors, such as terse communication or the disavowal patients’ distressful symptoms that have been so commonly employed by physicians historically [35].

In summary, clinically significant distress levels were present in the majority of house officers rotating on the hematology-oncology ward. Significant content themes were frustration (i.e., with the learning experiences or providing care with which they did not agree) and salient death-related events. The majority of house officers identified a death-related event as their IES-R (distress scale) event and also felt that these were the most stressful of the rotation. At the same time, the majority also derived a sense of meaning from working with dying patients. Future directions should include further study into the mechanism of medical provider distress (e.g., death-related phenomena), interventions to lessen provider distress, and to understand the role of meaning. Interventions could experientially process routine vicarious death trauma for the medical providers and enhance a derived sense of meaning, similar to a recent successful intervention study [36]. Patient-related outcomes secondary to diminished physician distress should also be explored.

References

Artiss KL, Levine AS. Doctor-patient relation in severe illness. A seminar for oncology fellows. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(23):1210–4.

Reilly JM, Ring J. An end-of-life curriculum: empowering the resident, patient, and family. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(1):55–62.

Quinal L, Harford S, Rutledge DN. Secondary traumatic stress in oncology staff. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(4):E1–7.

Redinbaugh EM, Sullivan AM, Block SD, et al. Doctors’ emotional reactions to recent death of a patient: cross sectional study of hospital doctors. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):185.

Sinclair HA, Hamill C. Does vicarious traumatisation affect oncology nurses? A literature review. Eur J Oncol Nurs Off J Eur Oncol Nurs Soc. 2007;11(4):348–56.

Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L. Oncologist burnout: causes, consequences, and responses. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1235–41.

Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, et al. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):177–83.

Dyrbye LN, Massie Jr FS, Eacker A, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1173–80.

Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236–42.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41(3):209–18.

Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–96.

Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Impact of event scale: psychometric properties. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2002;180:205–9.

Briere J, Woo R, McRae B, Foltz J, Sitzman R. Lifetime victimization history, demographics, and clinical status in female psychiatric emergency room patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185(2):95–101.

Corcoran KFJ. Measures for clinical practice: a sourcebook. Vol 2. 3rd ed. New York: The Free Press; 1994.

Briere J. Psychological assessment of adult posttraumatic states. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 1997.

Weiss D, Marmar C. The impact of events scales-revised. Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford; 1997.

Weiss D. The impact of event scale: revised. New York: Springer; 2007.

Chen CS, Yang P, Yen CF, Wu HY. Validation of impact of events scale in nurses under threat of contagion by severe acute respiratory syndrome. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(2):135–9.

Wallbank S, Robertson N. Predictors of staff distress in response to professionally experienced miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal loss: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(8):1090–7.

Hagh-Shenas H, Goodarzi MA, Farajpoor M, Zamyad A. Post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of Bam earthquake 40 days after the event. East Mediterr Health J La Revue de Sante de la Mediterranee Orientale Al-Majallah Al-sihhiyah Li-sharq Al-mutawassit. 2006;12 Suppl 2:S118–25.

John PB, Russell S, Russell PS. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among children and adolescents affected by tsunami disaster in Tamil Nadu. Disaster Manag Response DMR Off Publ Emerg Nurses Assoc. 2007;5(1):3–7.

Education AACfGM. 2015; http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/271/GraduateMedicalEducation/DutyHours.aspx.

Ripp JA, Bellini L, Fallar R, Bazari H, Katz JT, Korenstein D. The impact of duty hours restrictions on job burnout in internal medicine residents: a three-institution comparison study. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2015;90(4):494–9.

Parshuram CS, Amaral AC, Ferguson ND, et al. Patient safety, resident well-being and continuity of care with different resident duty schedules in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Med Can. 2015;187(5):321–9.

HC L. Educating competent and humane physicians Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1990.

Sekeres MA, Chernoff M, Lynch Jr TJ, Kasendorf EI, Lasser DH, Greenberg DB. The impact of a physician awareness group and the first year of training on hematology-oncology fellows. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;21(19):3676–82.

Armstrong J, Lederberg M, Holland J. Fellows’ forum: a workshop on the stresses of being an oncologist. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2004;19(2):88–90.

Fins JJ, Nilson EG. An approach to educating residents about palliative care and clinical ethics. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2000;75(6):662–5.

Liao S, Amin A, Rucker L. An innovative, longitudinal program to teach residents about end-of-life care. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2004;79(8):752–7.

Kobasa SC. Stressful life events, personality, and health: an inquiry into hardiness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1979;37(1):1–11.

Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–24.

Alvaro C, Lyons RF, Warner G, et al. Conservation of resources theory and research use in health systems. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5:79.

Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. A conceptual model of medical student well-being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry J Am Assoc Dir Psychiatr Residency Training Assoc Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53.

Kaufman DM. Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):213–6.

Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(8):1011–5.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174(4):527–33.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McFarland, D.C., Maki, R.G. & Holland, J. Psychological Distress of Internal Medicine Residents Rotating on a Hematology and Oncology Ward: An Exploratory Study of Patient Deaths, Personal Stress, and Attributed Meaning. Med.Sci.Educ. 25, 413–420 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0159-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0159-x