Abstract

Purpose of Review

This paper analyses the options to broaden the base of climate finance provided by countries in a mixed-methods review. It (1) reviews Non-Annex II countries’ commitments in international agreements, declarations, and agendas; (2) provides and applies a literature-based review of criteria to identify countries’ responsibilities and capabilities to provide finance; (3) reviews institutional affiliation; and (4) reviews countries’ willingness to provide finance through their contributions to 27 relevant multilateral funds.

Recent Findings

Scaling up climate finance has been a political and operational priority for the UN climate negotiations. However, the Annex II list of countries that commit to support developing countries financially with mitigation and adaptation has hardly changed since 1992. Given countries’ diverse emission pathways and economic development as well as geopolitical dynamics, Annex II is turning into a weakness of the UNFCCC in times when developing countries’ climate finance needs are increasing.

Summary

Our largely qualitative analysis indicates that Eastern European countries, Russia, South Korea, Türkiye, Monaco, and Gulf States (including Saudi Arabia) meet many justifications for further negotiations about the expansion of the climate finance provider base. However, we argue against a continued rigid dichotomy of providers and recipients. We recommend four innovations going forward, including establishing ‘net recipients’ as a third category; this 1) broadens the base; 2) increases climate finance; and 3) could increase effectiveness and cooperation. More research is needed on the role of countries’ vulnerability and debt levels in discussions on climate finance provision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scaling up ‘climate finance’ to support developing countries with mitigation and adaptation efforts has been a political and operational priority for the UN climate negotiations since 2009. In Copenhagen at the time, developed countries committed to mobilising US$100 billion of climate finance annually by 2020. At the negotiations in Paris (2015) it was decided to set a new collective quantified goal before 2025 [1, Decision 1/CP.21, paragraph 53] signifying and further increasing this importance [2].

The topic of climate finance has been studied extensively. Ample research exists on subtopics such as accountability [3,4,5,6], justice [7, 8] and the allocation of finance [9,10,11]. Less research exists on effort-sharing among climate finance provider countries [see e.g. 12 ,13]. As a subtopic, broadening the climate finance provider base receives even less attention. Three notable exceptions are Colenbrander et al. [14], Beynon [15] and Qi and Qian [16]. The former evaluates quantitative approaches for identifying countries’ responsibilities and capabilities to provide more climate finance. Beynon also quantifies these based on cumulative emissions and Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. In a journal publication, Qi and Qian analyse the shortcomings of the current climate finance architecture as well as China’s potential role in a new architecture.

The list of climate finance providers, ‘Annex II’ of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), has not changed since it was agreed on in 1992, with the exception of the removal of Türkiye in 2001 and indirectly with the succession of the European Economic Community (EEC) by the European Union (EU). Annex II contains 23 developed countries and the EU, a subset of the list of 43 Annex I Parties that assumed quantified mitigation commitments under the UNFCCC’s Kyoto Protocol. Just like the dichotomy between Annex I and Non-Annex I countries became increasingly dysfunctional over time [17, 18], the dichotomy between climate finance providers and recipients is turning into a weakness of the UNFCCC in addressing the climate crisis.

On the one hand, finance needs are increasing. The gap between the costs of mitigation and the available finance is particularly large in developing countries [19]. Similarly, the adaptation finance gap continues to widen [20]. Failure on mitigation and adaptation will raise costs of loss and damage (ibid.). This can partly be explained by Annex II countries not living up to their promises. The US$ 100 billion per year goal was only met in 2022 with two-year delay [21], according to the most optimistic account [3, 5, 22]. The US, Australia, Canada, Italy and Spain are ‘notable laggards’ in terms of delivering their share to the collective climate finance commitment [13].

On the other hand, the Annex II list is outdated and imprecise for three main reasons: countries’ shifting greenhouse gas (GHG) emission pathways and evolving economies, and a changing political order.

First, even though the GHG emissions of Annex II countries on average remain above Non-Annex II countries, most Annex II countries have been reducing their emissions in both absolute and per capita terms [23], including by transferring fossil fuel-driven emissions-intensive production to developing countries. The fast industrialization of some emerging economies has contributed to the share of global anthropogenic GHG emissions of developing countries from less than half in 1990 to almost three-quarters in 2019 [24]. Overall, global emissions have continued to rise, thus increasing the need for climate finance.

Second, national incomes have changed dramatically since 1992. Annex II countries held around four-fifth of the global GNI in 1992, but by 2020 this reduced to around half of the global GNI. Projections to mid-century show an inversion of economic power from the Group of 7 countries (G7: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, US), all in Annex II, to developing ‘Emerging 7’ countries (Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, Türkiye), with the latter economies representing up to twice the total size of the earlier group by 2050 [25]. Other developing countries such as Vietnam and Nigeria are also expected among the group of the 20 largest economies. Absolute GNI numbers do not necessarily reflect the relevance of countries’ larger population sizes (see also Supplementary Material). For instance, India ranks as the 5th largest economy in current US$ in the world in 2022, but still has almost 200 million people living in extreme poverty [26]. However, absolute GNI numbers can point to macroeconomic and political realities in which countries with large GNIs engage more actively in power dynamics, international cooperation, and potentially climate finance, in the context of setting and consolidating global agendas (see Sect. 3.2) [27, 28].

The point above has stimulated decentralisation and changes of power and decision-making structures that should come with a shift of some of the responsibility to deal with global issues such as climate change. On the one hand, initiatives such as the Bridgetown Initiative [29] and the Paris Pact for the People and the Planet [30] have pushed for the reform of the global financial architecture by largely focusing on institutions that precede the Convention, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), while others have contested that architecture by forming coalitions and alliances to reflect a changing order from the one in 1992, such as the G20, African Union, the (expansion of the) BRICS and others under the umbrella of South-South cooperation. On the other hand, international institutions use different classifications for groups of countries that seem unmoored from each other, complicating countries’ access to finance (including through eligibility), clarity of commitment and obligations, and allowing for venue shopping. For example, Israel, South Korea and Singapore do not have a developing country status under the IMF. Meanwhile, nineteen Non-Annex I countries are classified by the World Bank as high-income countries and therefore non-eligible to receive official development assistance (ODA). Among these, nine have an industrialised country status under UNIDO, including Trinidad and Tobago and Qatar [31].

This paper aims to identify potential countries to broaden the climate finance provider base through a mixed-methods review. First, based on an analysis of the Paris Agreement and seven other key international agreements, declarations and agendas (‘instruments’) on climate, environment and development, it reviews Non-Annex II countries’ commitments to provide finance.

Second, this paper reviews and applies the literature on potential criteria to identify countries’ responsibilities and capabilities to provide climate finance.

Third, it looks at institutional affiliation. In line with Michaelowa et al. [32], membership of the EU, the OECD, and/or the G20 is associated to larger political and economic power, and therefore considered as an indicator for increased responsibility to provide climate finance.

Finally, this paper reviews countries’ willingness to provide finance by analysing existing contributions to climate finance and other relevant international funds with a global reach, such as the Multilateral Fund of the Montreal Protocol and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

The aim of this study is explicitly not to identify fair shares of climate finance provision which, in the end, is always arbitrary and dependent on assumptions on criteria and how to apply them. However, aggregating review outcomes does point at potential Non-Annex II countries to broaden the future climate finance provider base in a changing global geopolitical context (see Table 5).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides more background on negotiations on climate finance and broadening its provider base under the UNFCCC. Section 3 provides the four reviews and summaries of the related methods (for a detailed explanation of the method, see the online Supplementary Material) and results. Section 4 aggregates the results and points at potential countries to broaden the climate finance base with. Section 5 concludes with a recommended way forward.

Climate Finance under the UNFCCC

Climate finance has been one of the most contentious issues in the UN climate negotiations. In the 1992 Convention, ‘developed country Parties and other developed Parties’ included in Annex II ‘shall provide new and additional financial resources’ to support developing countries in preparing their national communications to the UNFCCC, as well as the implementation of measures to combat climate change [33, Art. 4.3]. Further provisions on support in the Convention recognize that giving effect to the notion of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) involves more than a simple binary distinction between developed and developing countries, and encompasses multiple forms of differentiation according to countries’ circumstances [34, 28]. However, these provisions relate to climate finance recipients rather than its providers. For example, the Convention calls on developed countries to assist particularly vulnerable developing countries in meeting the costs of adaptation (Article 4.4) and to ‘promote, facilitate and finance’ technology access and transfer to ‘other Parties, particularly developing country Parties’ (Article 4.5). In the 2009 Copenhagen Accord, developed countries for the first time quantified pledges to mobilize climate finance: US$30 billion fast-start finance for the period 2010–2012 and US$100 billion annually by 2020 [35]. Ever since, scaling up climate finance towards this $100 billion target and the accounting of financial flows have been high political and operational priorities for the negotiations [3].

In Paris in 2015, developed countries signalled their intention to continue the collective goal to mobilise climate finance through 2025, and to establish a new collective quantified goal from a floor of US$100 billion per year prior to the 2025 UN climate conference (UNFCCC, 2015b, Decision 1/CP.21, paragraph 53). Negotiations on the size and nature of this new, quantified climate finance target happen in a context of developed countries failing to meet the annual target mobilisation of US$100 billion even by the most optimist account [5, 6]. While developed countries should continue to take the lead because of their historic GHG emissions and their high capabilities, there is an opportunity to discuss overall shortcomings of the current static system of climate finance, which includes the option to in-build some dynamism in reflection of present and future global contexts, leading to the invitation of more climate finance providers to the Table [2].

Broadening the Climate Finance Provider Base

Apart from two exceptions, the Annex II list has not been adjusted since 1992. First, as an OECD member, Türkiye was included under both Annex I and Annex II in the 1992 Convention. It only ratified the Convention in 2004 after it was taken off the Annex II list in 2002 considering its ‘early stage of industrialisation’ [36; decision 26/CP.7, 37]. Second, the EU succeeded the EEC that was originally listed as Annex II. Through the latter’s expansion, new members that were neither Annex I nor II such as Cyprus, Czechia, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco and Slovakia requested an amendment to the Convention to be included in the list of Annex I countries [38; dec. 4/CP.3, 39; Dec. 10/CP.17]. While no changes were made to Annex II, nine of the thirteen new EU members provided climate finance bilaterally in the period 2002–2021, totalling US$138.6 million and varying from US$0.034 million (Latvia) to US$ 77.8 million (Poland) [40]. In addition, these new EU member states have committed climate finance through the EU (around US$6 billion in 2021 [41]).

In the negotiations, Annex II countries have been attempting to broaden the climate finance provider base. For example, the Cancun Agreements of 2010 repeatedly refer to the provision of climate finance by ‘developed countries’ rather than ‘Annex II countries’ [42; e.g. paragraph 95 and 98]. It was also decided that financial resources for capacity-building should be provided by Annex II countries and by ‘other Parties in a position to do so’ (ibid, paragraph 131). However, the tension here is demonstrated by simultaneously noting that Annex I countries undergoing the process of transition to a market economyFootnote 1 are not included in Annex II to the Convention and as such are not subject to the provisions of Article 4.3 (ibid., Decision VI).

In negotiations that led to the Paris Agreement, country submissions by the EU and by the Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) in 2013 sought to include the broadening of countries contributing to climate finance and the national responsibility of all countries to mobilize finance [43]. These efforts were opposed on the grounds that a new agreement should not deviate from the Convention, which maintained the binary divide under the justifications that developing countries should not bear additional responsibilities and that developed countries should not weaken their commitments to provide climate finance. Terms to describe the role of other parties were also negotiated in Paris, including ‘voluntary contributions,’ ‘contributions by others in a position/willing/able to do so,’ and South-South cooperation [44]. As some countries expressed strong reservations, calling for consistency with existing provisions and principles of the Convention, it was in the end decided to encourage ‘Other Parties’ to ‘provide or continue to provide’ climate finance voluntarily [1; Art 9.2]. Meanwhile, the agreement states that developed countries (rather than Annex II countries) shall provide climate finance ‘in continuation of their existing obligations under the Convention’ (UNFCCC, 2015, art. 9.1) - even though under the Convention only Annex II countries shall provide such finance. In theory, this change in terminology broadens the climate finance provider base. In practice, however, the lack of formal agreement on which countries are ‘developed’ introduced additional ambiguity.

Meanwhile, discussions on broadening the climate finance provider base continue and expand to related topics. For example, in 2022 in Sharm-El Sheikh during the negotiations for a new funding to help address loss and damage, EU lead negotiator Timmermans said that ‘the pool of contributors should be broader than the list of countries defined by UN Climate Change as “developed” in the 1990s’ [45]. At the UN climate conference in Dubai in 2023 a dedicated loss and damage fund was established. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), presiding these negotiations, announced that it will commit $100 million to the fund, declaring that it was ‘paving the way for other nations to make pledges to the critically important Fund’ [46].

However, EU members Estonia and Slovenia were the only other Non-Annex II countries to make a pledge. This recent case with the loss and damage fund clearly demonstrated that a normative framework is lacking on who should contribute and why. This paper contributes to academic literature on global environmental governance, in particular the changing dynamics of the developed- developing country dichotomy. It also directly supports ongoing discussions and negotiations on expanding the current, static climate finance provider base. In doing so, the aim is to increase the volume of available climate finance with the help of new climate finance providers rather than to dilute existing responsibilities of developed countries.

Although private finance and domestic expenditure are increasingly relevant sources of finance to implement climate action [20], this paper only focuses on international public climate finance. Also, since this paper aims to contribute to ongoing negotiations under the UNFCCC, the analysis is limited to UNFCCC party countries only.

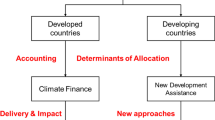

Four Ways to Identify Potential New Climate Finance Contributors

This section provides four reviews to identify potential Non-Annex II climate finance provider countries: commitments under international instruments (3.1); responsibility and capability (3.2); institutional affiliation (3.3); and willingness (3.4). The section ends with aggregated outcomes to point at potential Non-Annex II countries with which the climate finance provider base could be broadened in some form. The methods are explained in detail in the online Supplementary Material.

Changing Commitments under International Instruments

International agreements, declarations and agendas in the fields of development, environment and climate have always been characterised by a strong division between the Global North and the Global South. Since the 1970s, such international instruments have typically included clauses that describe how developed countries financially support developing countries with implementation [47]. Key examples include the 1970 agreement by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) that ‘economically advanced countries’ will progressively increase their ODA towards 0.7% of their gross national income [48; § 43]; the 1972 Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment and the 1989 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (ibid.). [47]. However, the developed- versus developing country dichotomy is fading. In a chronological order, this section analyses the most important international instruments on environment, climate and development. It only analyses instruments agreed since 2011 in order to capture most recent developments (for an explanation of the method, see the online Supplementary Material).

The outcome document of the fourth High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness (2011) states that ‘the world has changed profoundly since development co-operation began over 60 years ago’ (§ 4), referring to ‘a more complex architecture for development co-operation’ with co-operation among countries at different stages in their development, many of them middle-income countries. It mentions forms of cooperation that are complementary to North-South flows, such as South-South and triangular co-operation (§ 5). It also indicates that ‘a number of emerging economies have become important providers of South-South development co-operation’ (§ 14). However, the principles, commitments and actions agreed at the High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness ‘shall be the reference for South-South partners on a voluntary basis’ [50; paragraph 2]. Based on this outcome, Mawdsley et al. [51] argue that the ‘era of Western-dominated aid institutions and regimes is far from dead, but it is certainly starting to rupture’.

The outcome document of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) in 2012 also describes the changing aid architecture (UNGA, 2012). It reiterates support for South-South cooperation and triangular cooperation, as it provides ‘much-needed additional resources to the implementation of development programmes’. It also acknowledges the role played by middle-income developing countries as providers and recipients of development cooperation [52; § 260].

Apart from the Paris Agreement, three other important international instruments were agreed on development, environment and climate in 2015. First, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 states that ‘North-South cooperation, complemented by South-South and triangular cooperation, has proven to be key to reducing disaster risk and there is a need to further strengthen cooperation in both areas’ [53; § 44]. At the third Financing for Development conference in Adis Abeba [53; § 44]. At the third Financing for Development conference in Adis Abeba, it was agreed that South-South cooperation is complementary, not a substitution North-South cooperation. It labels South-South cooperation as ‘important’ and, in contrast to Rio + 20 where it was ‘supported’, it ‘encourages’ such cooperation.

Finally, the language is less strong on South-South cooperation in the Agenda 2030 and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). South-South cooperation is mentioned under technology (goal 17.6) and capacity building (goals 17.9), but the finance subgoals (17.1–17.5) only state that developed countries are to implement fully their ODA commitments (goal 17.2) and that additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources are to be mobilised (goal 17.3), without further explanation of these sources.

In 2016, countries agreed to the Kigali amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. A number of Non-Annex II countries are indicated as developed countries (i.e. not included in Article 5) (see Table 1). No changes were made on the provision of finance to the Multilateral Fund, which continues to be capitalised through voluntary contributions from non-Article 5 parties. Such contributions are requested on the basis of the United Nations scale of assessments [54]. As of 8 November 2023, these contributions totalled over US$ 4.7 billion, with additional voluntary contributions from other countries amounting to US $25.5 million [55].

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) of 2022 builds on the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, of 1992). In the CBD, countries can self-identify as developed countries and assume the related responsibilities. However, this list has not changed since 2006 [49]. Developed country Parties should provide new and additional financial resources to help developing country Parties to implement the CBD (ibid.). In GBF it was agreed to ‘substantially and progressively increase the level of financial resources’. In this context, Target 19a mentions developed countries (including through ODA) and developing country Parties that ‘voluntarily assume obligations of developed country Parties’.

Our review demonstrates that with exception of the Agenda 2030, recent international instruments on climate, environment and development consequently mention developing countries as complementary providers of finance to support other developing countries. While this is explicitly on a voluntary basis, the language gets stronger and more focused over time.

With exception of the UNFCCC, the CBD and the Montreal Protocol, none of the reviewed international instruments includes any Non-Annex II countries explicitly as developed countries, and none of the instruments specify particular Non-Annex II countries as finance providers (see Table 1). The UNCSD does acknowledge ‘Middle-income countries’ as climate finance recipients and providers. This is a diverse and dynamic group of countries, classified by the World Bank as having a GNI per capita (p.c.) between US$1,086 and US$13,205, and home to 75% of the global population [56].

Responsibilities and Capabilities

In sharing a common atmosphere, countries have contributed in different ways to causes and impacts of the global climate crisis. This has been at the core of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities [18], first inscribed in the Rio Declaration (1992) and further developed in the Convention and the Paris Agreement [1; Art. 2.2] to also include and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances. However, there is no agreed-upon approach to determine individual countries’ ideal levels of responsibility and capability for addressing climate change. Neither the literature nor political consensus provides a general answer on this. Based on a non-comprehensive literature review, this section first identifies ways in which responsibilities and capabilities are being measured in the literature, and then applies these to identify Non-Annex II countries with larger potential responsibilities and capabilities to provide climate finance.

Responsibility is generally associated with a country’s contribution to the climate crisis, deriving from its use of the global emission budget as a shared resource [57,58,59] and efforts to stay within these budgets as contributions to climate mitigation efforts [60, 61]. Countries’ use of the common atmosphere has been typically measured in terms of GHG emissions, which reflect historical factors such as the start year and speed of a country industrialisation, geographic factors such as climatic conditions, countries’ size and related needs in transportation, and availability of renewable resources [62], as well as socio-economic ones such as development and consumption patterns [63]. Complex interactions between these different factors have made responsibility an issue of climate justice, with a vast literature looking into different approaches that aim at reaching a ‘fair share’ level of emissions by each country based on principles such as equality and other principles of environmental law [64], climate liability [65] or national accountability [13].

Some of these studies are concerned with ideal levels of mitigation efforts, as it was essential for defining decarbonization under Kyoto Protocol’s system (e.g. [66,67,68]). Yet, responsibility from over-use of the global carbon budget also indicate a debt by overusing countries or need to compensate countries that have underused and by consequence had their budgets appropriated [69, 70]. The literature typically determines countries’ responsibility by using GHG emissions (total or per capita) and by applying various reference parameters. These can be categorised by time, absolute, and relative dimensions (see online Supplementary Material). In terms of time, GHG emissions are considered at current levels in a specific year (e.g., 2019), and as cumulative emissions starting from a certain year (e.g., 1990 [13]). Some studies analyse emissions since 1960 [69] or 1890 [71]. The choice of the starting year is important as it affects the relative cumulative emissions of early industrialized countries and emerging economies like China, India, and Brazil. In terms of scope, most studies focus on CO2 emissions. Some also include other GHGs like CH4, N20 [71] and SO2 [69]. Finally, the relative dimension describes the relationship of emissions to either population size or national income. Studies consider emissions per capita and emission intensity per unit of GNI [13] or gross domestic product (GDP) [32, 72]. Relative emissions based on population size or national income typically consider territorial emissions, which do not account for emissions embedded in traded goods. This generally underestimates the GHG emissions from countries with high consumption patterns. For example, in Europe, CO2 emissions per capita were 20% higher for consumption-based emissions compared to production-based emissions, whereas in Eastern Asia consumption-based emissions are 20% lower compared to production-based emissions in 2018 [24].

No single indicator covers all facets of “responsibility”. For example, countries’ relative shares derived from cumulative historic emissions do not reflect potentially relevant country aspects, including smaller population sizes and the type of economy. On the other hand, only looking at relative emissions ignores economic and political realities. For instance, Russia and Luxembourg, both emitting around 12tCO2 p.c. in 2022, have an almost a 200-fold difference in absolute emissions.Footnote 2 In order to cover all facets, this study uses three indicators (Table 2, column 1, 2, 3) for our comparative analysis in Sect. 4, incl. cumulative CO2 emissions in metric tons per capita between 1990 and 2019, CO2 emissions in tons per capita in 2019, and CO2 emissions in tons in absolute values in 2019. This is based on territorial emissions, and emissions from international aviation and shipping are excluded (see online Supplementary Material).

Countries’ capability to provide climate finance are not often discussed in the literature. The most common criterion used to reflect capability is the per capita income level expressed GNI [13, 70]. Other factors likely to be considered are the stage of development of capital markets [73], high capital costs [74], and financing constraints [75], incl. level of debt service, but the literature does not yet discuss these in the context of providing climate finance. Qian et al. [76] confirmed that economic development, measured by real income growth over time, significantly affects the potential to provide of international climate finance. In order to keep the approach comparable, we replicate the indicators for responsibilities by exchanging emissions with income. The identified parameters are: GNI as annual mean value for the reference period 1990–2019 (Table 2, column 4); GNI p.c. in 2019 (column 5), and GNI in absolute value in 2019 (column 6).

Following recent studies [13], we assign the decision “Yes”, for Non-Annex II countries in Table 2 when their values are above the median Annex II values (p50). Only countries with at least one positive decision (e.g., one parameter is above the median Annex II value (p50) are shown in Table 2.

It is important to note that there is always subjectivity in choosing which criteria should be used and why [49]. Our approach does not make any assumptions about the relative importance of indicators and weights them equally. However, the emission indicators (1, 2, and 3) also partially capturing capabilities to provide finance as emissions are largely associated with income levels [13].

Table 2 lists 47 Non-Annex II countries that meet at least one of the seven qualifiers. From a regional perspective, nine out of thirteen Middle Eastern countries are listed, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Kuwait, all of which have higher responsibility indicators (1–3) than the median Annex II emissions. Seven new EU member states and all BRICS countries are also listed.

On the three capability indicators (4–6), however, only a few Non-Annex II countries demonstrate values higher than the Annex II median. The annual average GNI of Annex II countries between 1990 and 2019 (column 4, threshold: current US$ 397 billion) is exceeded by all BRICS countries and Mexico, Indonesia and Türkiye. When only looking at 2019 values, Poland and Saudia Arabia score higher than the Annex II median. Only three countries (Qatar, Singapore, and Liechtenstein) had a higher GNI per capita in 2019 than the median Annex II (US$ 48,88 thousand), highlighting ongoing economic dominance of Non-Annex II countries. Saudi Arabia (US$ 45 thousand) and Israel (US$ 44 thousand) are slightly below the Annex II median.

Overall, the 47 Non-Annex II countries in Table 2 score 3.8x times more frequent on the responsibility (emissions) than on capability (income).Footnote 3 This means that Non-Annex II countries’ higher responsibility to provide climate finance might be inconsistent with their lower capability, and probably even more so when taking debt service levels or climate vulnerability into account.

Institutional Affiliation

While Sect. 3.2 analyses countries responsibility and capability quantitatively, these issues can also be analysed qualitatively through institutional affiliation (see [32]). For example, membership of the EU, OECD, or the G20 demonstrates considerable economic and political power which translates into interest to set and consolidate agendas [27, 28, 77] and can be considered as an indicator for increased responsibility to provide climate finance.

The G20 in its most recent communique recalls and reaffirms developed countries’ commitment to jointly mobilizing US$ 100 billion climate finance per year. However, it also recognises the ‘need for increased global investments to meet our climate goals of the Paris Agreement, and to (…) scale up investment and climate finance from billions to trillions of dollars globally from all sources’ (emphasis added) [78]. And while OECD membership as such does not entail an obligation to provide climate finance, new OECD member countries often join the OECD DAC – the list of countries that provide ODA. For example, South Korea became the first major ODA recipient to turn into an ODA donor after becoming a DAC participant in 2010. Slovenia (2012), Czechia, Iceland, Poland and Slovakia (2013), Hungary (2016), Lithuania (2022) and Estonia (2023) also joined the DAC. Such accession demonstrates these countries’ increasing responsibility in global development efforts and could set a precedent for climate finance provision.

This review only addresses institutional affiliation. Countries’ scores on, for example, the Human Development Index (HDI), the World Bank country classifications by income level, or the list of developed countries that is used for statistical purposes by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) are excluded here.

Figure 1 shows those Non-Annex II countries that are members of the G20, the OECD and/or the EU. None of the Non-Annex II countries are members of all three country groupings. However, Mexico, South Korea and Türkiye are both members of the OECD and the G20, and eight Eastern European countries have joined both the EU and the OECD in recent years. Finally, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile and Israel are member of only group (the OECD).

Willingness

This final review analyses countries’ willingness to provide climate finance. As a proxy, we evaluated previous contributions by Non-Annex II countries to 27 multilateral climate- environment- and development funds with openness to global contributions. That means that even when regionally focused, they can equally receive contributions from countries around the world. This data can be considered a proxy to countries’ willingness to contribute financially to global cooperation and the global commons. Meanwhile, since not corrected for countries’ population or the size of the economy, the data would not suffice for ranking countries, but only establishing as nominal data.

The data was sourced from Climate Funds Update, which includes cumulative data from 2003 up to January 2022 from 23 funds including the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF)Footnote 4. In addition, data from the Environment Fund (from 2010 to 2023), the Multilateral Fund (from 1991 to 2023), the Joint SDG Fund (2017 to 2023) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (or ‘Global Fund’, from 2001 to 2023) was included to gauge countries’ willingness to contribute to development and environment objectives in general – two topics that are highly related to climate change [79, 80]. Data comparability is constrained by three factors. First, these funds are a subset of all potentially relevant funds. For example, relatively new funds such as the public-private Global Fund for Coral Reefs (launched in 2020) were not included.

More importantly, public development banks (PDBs) - including national (NDBs) and multinational (MDBs) ones – are excluded from the analysis, even though they have been central for the global development and climate finance agendas [21] and although they receive contributions from various Non-Annex II countries [14]. This has two main reasons. First, contributions to different public development banks are normally limited to a closed group of shareholders. Second, the variety of PDBs in terms of access and funding mechanisms would require a specific methodology to classify and derive the willingness of Non-Annex II countries to contribute, falling out of the scope of this review to identify willingness to finance, rather than finance amounts provided.

Second, different data sources were used, which might cause inconsistencies (e.g. in exchange values of pledges in non-dollar currencies). Third, timeframes of funds are sometimes inconsistent. For example, some funds are replenished on an ad hoc basis (e.g. Adaptation Fund) and others in multi-year cycles (e.g. the GCF and the GEF). Similarly, the cut-off date for the Climate Funds Update data (January 2022) means, for example, that the second replenishment of the GCF is not included. However, the data quality is sufficiently high for this analysis given that the aim is to understand countries’ willingness to contribute, rather than to compare and rank such contributions.

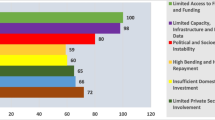

A total number of 168 countries and the EU/European Commission made contributions to at least one of the abovementioned funds, indicating a high willingness across countries to contribute financially to address global problems related to climate, development and environment. Amounts varied from Solomon Islands and Somalia (US$ 1000 to the Environment Fund) to the United States (US$ 23 billion to the Global Fund). Given the wide range, we differentiate between significant contributions (cumulatively > US$ 5 million) and symbolic contributions (cumulatively < US$ 5 million).

Significant Contributions

Twenty-five Non-Annex II countries provide significant contributions, twelve of which are high-income countries according to the World Bank classification (see Table 3). At an aggregate level, the top five contributing countries are: Russia (US$ 388 million), South Korea (US$ 259 million), Saudi Arabia (US$ 131 million), China (US$ 119 million), and India (US$ 94 million). While a ranking of countries contributions is impossible without further context as explained earlier, the quantities of contributions can be put in perspective by noticing that these contributions by Russia, South Korea, Saudi Arabia and China are higher aggregate contributions than the bottom five Annex II contributing countries: Iceland (US$ 7 million), Greece (US$ 37 million), Portugal (US$ 54 million), New Zealand (US$ 61 million) and Luxembourg (US$ 177 million).

The majority (68–99%) of the contributions by Russia, Saudi Arabia, China and India went to the Global Fund. South Korea channelled more than half of its contributions to the GCF, which has its headquarters there. The second-largest recipient of these contributors varies: Russia also contributed to the Multilateral Fund (12%), Saudi Arabia to the Environment Fund (1%), and China and India to the GEF (21% and 18% respectively). There seems to be hesitance among the top five providers towards climate finance. Indeed, only one country (South Korea) provides more to the GCF than the five Annex II countries with the lowest GCF contribution. For The GEF, there are four such countries (China, India, Mexico and Pakistan) and for the Global Fund even ten.

Symbolic Contributions

In addition to the significant contributions analysed above, 120 Non-Annex II countries make symbolic contributions (< US$ 5 million) in aggregate to the analysed funds (See Table 4). Note that a symbolic contribution can be large in volume for the country that provides it, especially when this is a poorer country. Eighteen low-income countries provided symbolic contributions. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo provided US$ 4 million to the Global Fund and Afghanistan provided US$ 0,005 million to the Environment Fund.

On the other hand, there are also countries where institutional affiliation indicates a certain level of responsibility that is not reflected in the demonstrated willingness to provide finance. G20 countries Brazil and Indonesia only provide symbolic contributions. Similarly, relatively new OECD member countries Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica all provide less than US$ 1 million.

Although limited in volume, symbolic contributions can be important. For example, the symbolic contributions of e.g. Chile, Indonesia and Mexico provided impetus to the Green Climate Fund during its initial resource mobilisation in 2014 and in the run up to the UN climate negotiations in Paris. Similarly, pledges by Scotland ($2.3 and $5.7 million) to support action against loss and damage were small in volume but have helped in paving the way for a dedicated fund on loss and damage under the UNFCCC.

Comparative Results

Table 5 aggregates the results of the four reviews (Sect. 3.1 to 3.4) in a qualitative way. The number of justifications per country provide insights in the potential countries to broader the climate finance provider base with. This outcome is partly dependent on assumptions. For example, significant financial contributions are not put in the perspective of contributors’ GNI or population; and it looks at the period 1990–2019 for per capita emissions and GNI. Under the UNFCCC, however, countries never reached agreement on how responsibility or capability should be expressed.

Table 5 is nevertheless a discussion starter for two reasons. First, it provides insight in the arguments based on which a long-list of 63 countries could become climate finance providers. Second, the more justifications behind an individual country, the stronger the case to add it as a climate finance provider under the New Collective Quantified Goal and/or in the context of the new fund on Loss and Damage. A number of countries stand out.

Eastern European countries, in particular Czechia, Poland, Estonia and Slovenia are logical additions to the climate finance provider base. Institutionally, these Annex I countries under the UNFCCC have joined both the OECD and the EU and have shown willingness to provide climate finance either voluntary or as part of the EU in recent years.

Russia is a developed country under the UNFCCC and the Montreal Protocol with a large responsibility for climate change but a lower capability. It has demonstrated willingness to provide significant financial contributions.

South Korea justifies as a new climate finance provider because of the institutional affiliation (G20 and OECD membership), its responsibility and capability and its demonstrated willingness to provide climate finance, in particular to the GCF with its headquarter in South Korea.

Türkiye, the country that was taken off Annex II in 2001, is a large economy as reflected in its G20 and OECD membership and its high capability and its rising GHG emissions could surpass the median Annex II GHG emissions per capita in the near future.

Monaco is a developed country under three international agreements and its (aggregated) per capita emissions are higher than the Annex II median. It demonstrated willingness to provide significant financial contributions. At the same time, its economy and population are relatively small, implicitly meaning that absolute contributions will be modest. The European countries San Marino and Liechtenstein have similar circumstances.

Gulf States Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have both high emissions and per capita GNIs. These countries have already demonstrated willingness to make significant contributions, including to the Environment Fund and the Global Fund. Saudi Arabia is also part of the G20.

At the same time, some countries appear less likely to broaden the climate finance provider base. The G20 member India has larger absolute emissions and a larger economy than the Annex II median and have shown the willingness to provide significant support, but do not score on any of the other justifications. Other emerging economies such as Argentina, Brazil and Indonesia (all G20 countries), as well as Chile and Colombia (both OECD member countries) also only meet two or three justifications based on the large-population related size of their economy.

Conclusion and Way Forward

This paper reviewed international instruments, countries’ responsibilities and capabilities, institutional affiliation as well as countries’ willingness to provide climate finance, in order to identify potential countries to broaden the climate finance provider base under the UNFCCC.

Our findings underscore that any way forward requires a nuanced dialogue (see also Colenbrander et al. [13]). It shows that there are some natural candidates to broaden the base with, such as new EU member states (in particular, Czechia, Poland, Estonia and Slovenia), Russia, South Korea, as well as Gulf states (in particular Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates). This is based on a largely qualitative assessment. This paper explicitly refrains from suggesting climate finance quantities that these countries should provide as fair shares based on particular assumptions on responsibility and/or capability. While such analyses are helpful to generate insights (see e.g. [15]), UNFCCC negotiations on countries’ fair shares in climate change mitigation have proven a dead end because countries will never be able to agree on how to measure responsibility and how to measure capability. Similarly, it is highly unlikely that countries will ever agree on ‘fair shares’ for climate finance provision.

Our analysis also demonstrates that any broadening will to a certain extent be arbitrary and therefore subject to discussion at the UNFCCC. This level of arbitrariness makes it even more important that Annex II countries deliver on existing climate finance pledges as a means for building trust in the system. Non-compliance will strengthen the negotiation position of Non-Annex II countries that oppose becoming a climate finance provider [81].

This point is also underlined by the fact that only a small number of countries rank positively against Non-Annex II countries in terms of GNI (Table 2). Economic inequality between Annex II and non-Annex II countries continues to persist, despite the ongoing economic and political development of emerging economies (as explained in the introduction). If we are to timely address the pressing global needs of emissions reductions; adaptation; and averting, minimising and reducing losses and damages, the contribution of developed countries should remain central to any type of agreement around the NCQG.

Only a limited number of potential countries can be justified consistently as potential new climate finance providers in our analysis. We have not addressed the question how new climate finance providers could be integrated in the financial architecture of the UNFCCC. Broadening the provider base could be formalised by including additional countries in a new formal list that builds on Annex II. Weaker forms such as a separate list that names (potential) new providers or increased transparency or reporting requirements on current voluntary support would also be an advance. We would warn against continued bifurcation and rigidity, and recommend four innovations going forward.

First, we suggest establishing ‘net recipients’ as a third category next to the current ‘providers’ and ‘recipients’ in UNFCCC negotiated text. A net recipient is a country that makes either symbolic or significant financial contributions to climate finance but is able to receive finance as well. This has three main benefits. First, it will increase the total pool of resources. For example, if ten countries make contributions of 10 million on average annually, this already adds up to 1 billion per decade. Second, net recipients can help improve the quality and effectiveness of climate finance. On the one hand, they can finance projects on issues they excel in (for example, China in renewable energy) and would only receive finance in sectors or regions where they need it most. Third, it moves the discussion from the highly political developed- versus developing country dichotomy towards a more balanced climate finance system in which willingness and collaboration become more important and the notion of CBDR-RC is better reflected. In the same vein, an additional category of ‘net providers’ could be thought of for new providers of climate finance. These countries would continue to be eligible to receive climate finance and not have the same responsibilities as the Annex II countries currently have.

Second, it is important to acknowledge contributions that are small relative to the total amount of mobilised climate finance (‘symbolic’ in Sect. 3.4.2), but substantial for the countries who provide them. They demonstrate such countries’ willingness to contribute to addressing the global problem that climate change has become. Given that symbolic contributions can stimulate global cooperation on climate change (see the examples on the GCF and loss and damage in Sect. 3.4.2), the climate finance architecture should be more open and more graceful towards such contributions.

Third, certain countries can be excluded from providing climate finance [15]. In its simplest form, this could be done based on countries’ low emissions (per capita or total, aggregate or actual), GNI (per capita or absolute) and/or institutional affiliation (e.g. membership of the LDCs or SIDS). For example, Bangladesh would be excluded from Table 5 as an LDC, and Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan would be excluded when taking their eligibility for support by the International Development Association (IDA) as a proxy. As more comprehensive criteria for exclusion, issues such as countries’ level of climate change vulnerability or countries’ debt service levels could also be considered. Exclusion of particular countries will probably increase such countries’ support for reform of the climate finance provider base.

Finally, it is important to look forward. Finance needs for mitigation and adaptation continue to increase; and mid-century economic power might be inversed from the G7 countries - all Annex II countries with declining emissions- to emerging economies [25]. Bringing in new climate finance providers will be necessary at some (arbitrary) point in time and the setting of the NCQG provides an important window of opportunity to do so. If this is currently still a bridge too far, negotiators should at least agree on a year or a basis on which this decision will be reconsidered.

While our analysis can help to spur the debate on broadening the climate finance provider base, it is by no means comprehensive. More research should be conducted on at least three issues. First, an assessment of contributions to Public Development Banks, including NDBs and MDBs, would shed more light on Non-Annex II country willingness to provide climate finance. Second, an inverse analysis of what this paper has done could clarify which countries could be excluded from becoming climate finance providers. And finally, additional arguments for becoming or not becoming a climate finance contributor could be examined, such as countries’ level of vulnerability to climate change, countries’ debt levels, debt service rates, as well as their long-term debt ratings. Countries with high credit ratings, such as AAA or AA, have better access to financial markets and potentially excess savings. This allows them to follow counter-cyclical climate investment paths and provide international climate finance. Conversely, countries with lower credit ratings, such as BBB or lower, have lower access to global savings pools due to higher risk perceptions.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

Fourteen countries undergoing the process of transition to a market economy in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse: Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine.

Total CO2 emissions in million tons in 2019: 1,792.02 in Russia and 9.74 in Luxembourg [82].

The 47 countries have 79 times a positive (“Yes”) decision across the 3 emission indicators; and 21 times a positive (“Yes”) decision across the 3 income indicators: 73/21 = 3.8x.

Data includes the following funds: Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme (ASAP) and ASAP+, Adaptation Fund, Amazon Fund, BioCarbon Fund, Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), Clean Technology Fund (CTF), Congo Basin Forest Fund (CBFF), Forest Carbon Partnership Facility – Readiness Fund (FCPF-RF), Forest Carbon Partnership Facility – Carbon Fund (FCPF-CF), Forest Investment Program, Global Environment Facility (GEF), Global Climate Change Alliance, Global Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fund, GCF, Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (ICCTF), Least Developed Countries Fund, MDG Achievement Fund, Partnership for Market Readiness, Pilot Program for Climate Resilience, Scaling-Up Renewable Energy Program for Low Income Countries, Special Climate Change Fund, UN-REDD Programme.

References

UNFCCC. Adoption of the Paris Agreement [Internet]. 2015. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf.

Pauw WP, Moslener U, Zamarioli LH, Amerasinghe N, Atela J, Affana J-PB et al. Post-2025 climate finance target: how much more and how much better? Clim Policy [Internet]. 2022; https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2114985.

Weikmans R, Roberts JT. The international climate finance accounting muddle: is there hope on the horizon? Clim Dev [Internet]. 2019;11:97–111. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tcld20.

Roberts JT, Weikmans R, Robinson S ann, Ciplet D, Khan M, Falzon D. Rebooting a failed promise of climate finance. Nat Clim Chang [Internet]. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00990-2.

Oxfam. Climate Finance shadow Report 2023 [Internet]. 2023. https://www.oxfamnovib.nl/Files/rapporten/2020/Climate Finance Shadow Report - English - Embargoed 20 October 2020.pdf.

OECD. Aggregate Trends of Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013–2020. Paris, France; 2022.

Khan M, Robinson S, ann, Weikmans R, Ciplet D, Roberts JT. Twenty-five years of adaptation finance through a climate justice lens. Clim Change. 2019;251–69.

Gifford L, Knudson C. Climate finance justice: international perspectives on climate policy, social justice, and capital. Clim Change. 2020;161:243–9.

Halimanjaya A. Allocating climate mitigation finance: a comparative analysis of five major green donors. J Sustain Financ Invest [Internet]. 2016;6:161–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1201412.

Schwager S. Allocating climate finance: a contributor’s view. In: Michaelowa A, Sacherer A-K, editors. Handb Int Clim Financ. Edward Elgar Publishing; 2022. pp. 318–32.

Klöck C, Molenaers N, Weiler F. Responsibility, capacity, greenness or vulnerability? What explains the levels of climate aid provided by bilateral donors? Env Polit [Internet]. 2018;27:892–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1480273.

Pickering J, Jotzo F, Wood PJ. Sharing the Global Climate Finance Effort fairly with limited coordination. Glob Environ Polit. 2015;15:39–62.

Colenbrander S, Pettinotti L, Cao Y. A fair share of climate finance? An appraisal of past performance, future pledges and prospective contributors [Internet]. London, UK: ODI; 2022. https://odi.org/en/publications/a-fair-share-of-climate-finance-an-appraisal-of-past-performance-future-pledges-and-prospective-contributors/.

Colenbrander S, Pettinotti L, Cao Y, Robertson M, Hedger M, Gonzalez L. The New Collective Quantified Goal and its Sources of Funding - How could a ‘collective effort’ be operationalized in the NCQG? London, UK; 2023.

Beynon J. Who Should Pay? Climate Finance Fair Shares [Internet]., Washington DC. 2023. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/who-should-pay-climate-finance-fair-shares.

Qi J, Qian H. Climate finance at a crossroads: it is high time to use the global solution for global problems. Carbon Neutrality. 2023;2.

Depledge J, Yamin F. The global climate change regime: a defence. In: Helm D, Hepburn C, editors. Econ Polit Clim Chang. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 433–53.

Pauw P, Bauer S, Richerzhagen C, Brandi C, Schmole H. Different Perspectives on Differentiated Responsibilities [Internet]. Discuss. Pap. Bonn, Germany; 2014. http://mitigationpartnership.net/sites/default/files/dp_6.2014._0.pdf.

UNEP. Emissions gap Report. Nairobi, Kenya; 2022.

UNEP. Adaptation Gap Report 2023. Adapt. Gap Rep. 2023. Nairobi, Kenya; 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2016–2020 [Internet]. OECD. Paris, France. 2024. https://www.oecd.org/environment/climate-finance-provided-and-mobilised-by-developed-countries-in-2016-2020-286dae5d-en.htm.

Mitchell I, Wickstead E. Has the $ 100 Billion Climate Goal Been Reached ? Washington D.C.; 2024.

UNFCCC. Compilation and synthesis of fourth biennial reports of Parties included in Annex I to the Convention. Online. Bonn, Germany; 2020.

IPCC. Climate Change 2022, Mitigation of Climate Change Summary for Policymakers (SPM) [Internet]. Cambridge Univ. Press. 2022. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/.

PwC. The Long View: How will the global economic order change by 2050? Pwc. 2017.

the World Bank. Poverty and Inequality Platform [Internet]. 2024. https://pip.worldbank.org/home.

van Noort C. The Construction of Power in the Strategic Narratives of the BRICS. Glob Soc [Internet]. 2019;33:462–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2019.1581733.

Rinaldi AL, Apolinário Júnior L. Uma análise comparativa dos países do BRICS no campo de cooperação internacional para o desenvolvimento. Conjunt Austral. 2020;11:8–27.

Barbados B. 2022. https://pmo.gov.bb/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-2022-Bridgetown-Initiative.pdf.

Paris Pact for the People and the Planet. Paris Pact for the People and the Planet [Internet]. 2024. https://pactedeparis.org/en.php.

Farias D. Developing Countries Database (version 2022.1). [Internet]. 2022. https://www.developingcountries.info/.

Michaelowa A, Butzengeiger S, Jung M, Dutschke M. Beyond 2012–Evolution of the Kyoto Protocol Regime [Internet]. Berlin; 2003. http://www.globalrat.de/wbgu_sn2003_ex02.pdf%5Cnpapers2://publication/uuid/3DDBAE83-0240-4500-891A-3CF09941B263.

United Nations. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992.

Bodansky D, Brunnée J, Rajamani L. International Climate Change Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

UNFCCC. Report of the Conference of the Parties on its fifteenth session, held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009. UNFCCC. Bonn, Germany; 2009.

UNFCCC. Report of the conference of the parties on its seventh session, held at Marrakesh from 29 october to 10 november 2001. Bonn, Germany; 2001.

UNFCCC, Proposal to amend Annexes I. and II to remove the name of Turkey and to amend Annex I to add the name of Kazakhstan [Internet]. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-convention/history-of-the-convention/proposal-to-amend-annexes-i-and-ii-to-remove-the-name-of-turkey-and-to-amend-annex-i-to-add-the-name.

Conference of the Parties. Parties C of the. Report of the Conference of the Parties on its third session, held at Kyoto from 1 to 11 December 1997. Addendum Part Two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its third session. Methodol. issues Relat. to Kyoto Protoc. Bonn, Germany; 1998.

UNFCCC. Report of the Conference of the Parties on its seventeenth session, held in Durban from 28 November to 11 December 2011. Bonn, Germany; 2012.

Atteridge A, Savvidou G, Sadowski S, Gortana F, Meintrup L, Dzebo A. Aid Atlas [Internet]. Stock. Environ. Inst. 2019. https://aid-atlas.org.

European Council. Council approves 2021 climate finance figure [Internet]. 2022. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/10/28/council-approves-2021-climate-finance-figure/.

UNFCCC. Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of the Parties session. held in Cancun from 29 November to Part Two : Action taken by the Conference of the Parties The Cancun Agreements : Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Coo. Bonn, Germany; 2010.

Zamarioli LH, Pauw WP, Koenig M, Chenet H. The climate consistency goal and the transformation of global finance. Nat Clim Chang [Internet]. 2021;11:578–583. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-021-01083-w.

IISD. Summary of the Paris Climate Change Conference: 29 November – 13 December 2015 [Internet]. Earth Negot. Bull. 2015. http://www.iisd.ca/download/pdf/enb12663e.pdf.

Farand C. EU opens the door to a loss and damage facility – if China pays [Internet]. Clim. Home News. 2022. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2022/11/16/frans-timmermans-eu-is-open-to-loss-and-damage-fund/.

COP28. COP28 Presidency unites the world on Loss and Damage [Internet]. 2023. https://www.cop28.com/en/news/2023/11/COP28-Presidency-unites-the-world-on-Loss-and-Damage.

Pauw WP. From public to private climate change adaptation finance adapting finance or financing adaptation? Utrecht University; 2017.

UN General Assembly. International Development Strategy for the Second United Nations Development Decade. Resolution 2626 (XXV), 24 October 1970 [Internet]. New York, USA. 1970. http://www.un-documents.net/a25r2626.htm.

Barros Leal Farias D. Unpacking the. ‘developing’ country classification: origins and hierarchies. Rev Int Polit Econ [Internet]. 2023;0:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2246975.

Busan Partnership. Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation [Internet]. 2011. https://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/49650173.pdf.

Mawdsley E, Savage L, Kim SM. A post-aid world? Paradigm shift in foreign aid and development cooperation at the 2011 Busan High Level Forum. Geogr J. 2014;180:27–38.

UN General Assembly. The Future We Want. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 27 July 2012. New York, USA; 2012.

UN General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [Internet]. New York, USA. 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld.

Patlis JM. Multilateral Fund of the Montreal Protocol: A Prototype for Financial Mechanisms in Protecting the Global Environment, The. Cornell Int Law J [Internet]. 1992;25. http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/cintl25&id=191÷=&collection=.

Multilateral Fund. Welcome to the Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol [Internet]. 2023. http://www.multilateralfund.org/default.aspx.

The World Bank. The World Bank in Middle Income Countries [Internet]. 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mic.

Ostrom E, Dietz T, Dolšak N, Stern PC, Stonich S, Weber EU, editors. The drama of the commons. The drama of the commons. Ostrom, Elinor: Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Center for the study of institutions, Population and Environmental Change. Indiana University, IN, US: National Academy; 2002.

Messner D, Schellnhuber J, Rahmstorf S, Klingenfeld D. The budget approach: a framework for a global transformation toward a low-carbon economy. J Renew Sustain Energy. 2010;2.

Young O. Does fairness matter in international environmental governance? Creating an effective and equitable climate regime. In: Cherry TL, Hovi J, McEvoy DM, editors. Towar a New Clim Agreem. 2014.

Barrett S, Dannenberg A. Climate negotiations under scientific uncertainty. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Feb 8];109:17372–6. Available from: www.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1208417109.

Stone RW. Risk in International politics. Glob Environ Polit. 2009;9:40–60.

Neumayer E. National carbon dioxide emissions: geography matters. 2004 [cited 2024 Feb 8];36:33–40. https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00317.x.

Raupach MR, Marland G, Ciais P, Le Quéré C, Canadell JG, Klepper G, et al. Global and regional drivers of accelerating CO2 emissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10288–93.

Holz C, Kartha S, Athanasiou T. Fairly sharing 1.5: national fair shares of a 1.5°C-compliant global mitigation effort. Int Environ Agreements Polit Law Econ [Internet]. 2018;18:117–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-017-9371-z.

Grasso M, Heede R. Time to pay the piper: Fossil fuel companies’ reparations for climate damages. One Earth [Internet]. 2023;6:459–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.04.012.

Aldy JE, Barrett S, Stavins RN, 13 + 1:. A Comparison of Global Climate Change Policy Architectures. Resour. Futur. 2003.

Michaelowa A, Tangen K, Hasselknippe H. Issues and Options for the Post-2012 Climate Architecture – An Overview. Int Environ Agreements Polit Law Econ [Internet]. 2005;5:5–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-004-3665-7.

Torvanger A, Godal O. An Evaluation of Pre-Kyoto Differentiation Proposals for National Greenhouse Gas Abatement Targets. Int Environ Agreements [Internet]. 2004;4:65–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:INEA.0000019056.43577.b2.

Matthews HD. Quantifying historical carbon and climate debts among nations. Nat Clim Chang [Internet]. 2016;6:60–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2774.

Fanning AL, Hickel J. Compensation for atmospheric appropriation. Nat Sustain [Internet]. 2023;6:1077–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01130-8.

Müller B, Höhne N, Ellermann C. Differentiating (historic) responsibilities for climate change. Clim Policy. 2009;9:593–611.

Callahan CW, Mankin JS. National attribution of historical climate damages. Clim Change [Internet]. 2022;172:40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03387-y.

Prince Modugu K, Dempere J. Monetary policies and bank lending in developing countries: evidence from Sub-Sahara Africa. [cited 2024 Feb 8]; http://creativecommons.

Ameli N, Dessens O, Winning M, Cronin J, Chenet H, Drummond P et al. Higher cost of finance exacerbates a climate investment trap in developing economies. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 27];12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24305-3.

Mertzanis C. Financialisation, institutions and financing constraints in developing countries. Cambridge J Econ [Internet]. 2019;43:825–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez015.

Qian H, Qi J, Gao X. What determines international climate finance? Payment capability, self-interests and political commitment. Glob Public Policy Gov [Internet]. 2023;3:41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43508-023-00062-5.

Skovgaard J. The economisation of Climate Change: how the G20, the OECD and the IMF. Econ. Clim. Chang. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

G20. G20 New Delhi leaders’ declaration. India: Ne Delhi; 2023.

Schipper ELF, Tanner T, Dube OP, Adams KM, Huq S. The debate: Is global development adapting to climate change? World Dev Perspect [Internet]. 2020;18:100205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100205.

Liu J, Hull V, Godfray HCJ, Tilman D, Gleick P, Hoff H et al. Nexus approaches to global sustainable development. Nat Sustain [Internet]. 2018;1:466–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0135-8.

Walsh S, Tian H, Whalley J, Agarwal M. China and India’s participation in global climate negotiations. Int Environ Agreements Polit Law Econ. 2011;11:261–73.

Crippa M, Guizzardi D, Muntean M, Schaaf E, Solazzo E, Monforti-Ferrario F et al. Fossil CO2 emissions of all world countries [Internet]. Luxemb. Eur. Comm. 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their time and effort. Their comments and suggestions have helped tremendously in improving this paper. We thank the Dutch ministry of Foreign Affairs for their financial support to conduct this study.

Funding

This research was funded through the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ARVODI 395430.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The method was conceptualised by the team as a whole. W.P.P. was responsible for Sect. 3.1. M.K. was responsible for Sect. 3.2. W.P.P was responsibile for Sect. 3.3. M.V was responsible for the Sect. 3.4. W.P.P and L.H.Z. were responsible for the other sections. All authors provided comments and suggestions on the paper moving forward.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pauw, W.P., König-Sykorova, M., Valverde, M.J. et al. More Climate Finance from More Countries?. Curr Clim Change Rep 10, 61–79 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-024-00197-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-024-00197-5