Abstract

Mental accounting refers to a set of cognitive processes in which people code, categorize and evaluate money depending on where it came from and what they are going to spend it on, and this influences the way they make decisions. The concept of mental accounting violates the principles of standard economic theories, which consider money to be fungible or interchangeable. When people mentally account, they prefer to keep accounts separate and not to move money from one mental account to another. The current study aimed to investigate how people mentally account by designing a tax compliance laboratory experiment and using a variety of scenarios. In the first scenario, which involved different tax rate variations, participants were asked to pay tax on their earned and capital incomes. The results showed that participants formed separate mental accounts and treated their earned and capital incomes differently. Specifically, when faced with high tax rates of 60%, tax evasion was significantly higher for earned (labour) incomes compared to capital incomes. This willingness to cheat in order to protect labour income, suggests that individuals value their earned income more compared to income received from a given endowment (capital income). Interestingly, in subsequent scenarios involving different audit probabilities and fine rates, no mental accounting effects were found. In conclusion, this study provides initial experimental insights into the effects of mental accounting on taxpayer’s compliance, but further research is needed to explain nuanced findings and investigate tax decisions for different reference points and other sources of income.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental accounting, a concept introduced by Richard H. Thaler in 1985, explores the complex ways individuals perceive and manage their financial resources. It attempts to explain the process whereby individuals code and categorize money into different mental accounts based on criteria such as source of the money and the intended use of each account (Thaler 1985). This theory suggests that individuals organize their finances into separate mental compartments, each designated for specific purposes, thereby influencing their decision-making processes.

Over the years, many econometric models have been developed to understand how mental accounting influences decision-making in various situations. However, despite their complexity, these models often struggle to fully explain mental accounting. This is mainly because they tend to neglect the psychological aspects that are inherent in the mental accounting process. Additionally, there is a lack of empirical evidence from experimental studies to support these models. As a result, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of the complex relationship between psychological mechanisms and economic decision-making processes.

Understanding the psychological basis of mental accounting involves examining 2 fundamental economic theories: expected utility theory (formulated by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738) and prospect theory (pioneered by Kahneman and Tversky in 1979). Expected utility theory argues that individuals make decisions based on the utility they derive from various choices, regardless of the source of money (Stearns 2000). By contrast, Prospect theory assumes that decision outcomes are assessed in relation to a reference point that separates the value function into loss and gain domains (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Tversky and Kahneman 1985). Therefore, individuals’ behaviour is influenced by whether they perceive themselves to be in a domain of gains or losses, which can lead to either risk-averse or risk-seeking behaviour accordingly. The distinction between risk aversion in the domain of gains and risk seeking in the domain of losses has important implications for decision-making and behaviour in various contexts. Mental accounting potentially influences individuals to categorize their financial outcomes as either gains or losses. Consequently, it may shape aspects such as financial choices, investment decisions, and even everyday consumer behaviours (Kahneman 2002; Page et al. 2014).

One area, where the impact of mental accounting is particularly evident, is in tax compliance behaviour (Hikmah et al. 2021; Kirchler 2007; Webley and Ashby 2010). Taxes, imposed on various sources of income, prompt individuals to navigate complex decision-making scenarios. For example, research suggests that taxpayers often mentally separate taxes from their earnings, treating them differently. This cognitive separation might influence tax compliance behaviours, leading to varying levels of honesty in reporting income to tax authorities. Therefore, the current paper aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the role of mental accounting in decision-making processes, with a specific focus on its implications for tax compliance behaviour.

Theoretical background

Mental accounting can influence tax compliance behaviour, as taxes apply to different sources of income and individuals tend to treat these sources of income differently. Evidence suggests that taxpayers mentally segregate taxes from their turnovers and do not consider them as income (Olsen et al. 2019). For instance, Ashby and Webley (2008a, 2008b) conducted a qualitative study with hairdressers, beauticians, and taxi drivers to explore their compliance with reporting tips as income. Their results showed that a substantial number of participants acknowledged low compliance, mainly due to their perception of tips as gifts from customers, rather than mentally categorizing them as taxable income. In addition, Chambers and Spencer (2008) observed that when individuals receive monthly tax refunds, they usually spend them on monthly expenses. Conversely, if they receive a yearly refund as a lump sum, they are more prone to saving it or using it to settle debts. Additional research has investigated the effects of references points on tax compliance behaviour. For instance, Burt, Thorne, and Walker (2023) explored how different cognitive interpretations of reference points and tax withholdings impact aggressive tax filing. Their findings showed that the likelihood of filing taxes more aggressively is linked to how taxpayers mentally categorize whether they anticipate receiving a tax refund or owe additional taxes compared to their anticipated asset position. It was shown that aggressive filing behaviour is more common among taxpayers who are in a situation where they have incurred a tax loss compared to their expected asset position, and among those who do not differentiate between taxes owed and their personal resources.

In another study, Burt, Thorne, and Walker (2017), examined how a reference point can influence honest and dishonest behaviour in tax compliance. They categorized honest tax filing as risk-averse behaviour and dishonest filing as risk-seeking behaviour. Participants were presented with 2 tax scenarios: 1 offering a 5% chance of reduced tax liability and the other a 20% chance. Despite the varying probabilities, participants were informed of a 50% chance of detection, leading to additional taxes and penalties. Burt et al. found that taxpayers mentally framed their tax position as either a gain or loss, influencing their honesty level. In addition, their findings showed that viewing taxes as owed to authorities prompted more honest reporting. This shows how taxpayers used reference honesty points to make decisions, highlighting how prospect theory helps understand taxpayer behaviour. Mental accounting can also affect tax compliance decisions by determining the reference point (Muehlbacher et al. 2017). When taxes are mentally separated from income, individuals focus on net income after taxes, viewing tax evasion as a potential gain with the risk of penalties. On the other hand, if taxes are mentally integrated with income, gross income becomes the reference point, making tax payment feel like a loss and tax evasion less risky (Muehlbacher et al. 2017).

Maciejovsky, Kirchler and Schwarzenberger, (2001) also studied mental accounting in the context of tax compliance behaviour and examined if people form separate mental accounts for sale revenues (income gained through selling assets) and for dividend earnings (income gained through profits given to shareholders). They were also interested to see if an increase in tax penalty or audit frequency rates would lead to a higher level of tax compliance. In their experiment, participants were asked to sell and buy assets in an experimental market situation and then they had to declare taxes on their revenues and dividend incomes separately. Although findings of this experiment indicated no statistically significant difference between these 2 sources of income and showed that participants did not form separate mental accounts for their sale revenues and for their dividend earnings, the participants declared less taxes to the tax authorities when their net asset holding had been increased by purchasing assets. These findings are aligned with the framework of prospect theory, in which people normally consider tax payments related to sales revenues as a subjective loss due to the obligation of paying tax on a hard-earned income. Therefore, due to risk-seeking behaviour, individuals tend to try to increase their asset holdings by buying more assets rather than giving them up (Maciejovsky et al. 2001). In addition to the above findings, Maciejovsky et al. (2001) found a positive relationship between tax compliance behaviour and different rates of tax penalty (50% payment of evaded income versus 100% payment of evaded income) and audit frequency (17% chance of being audited versus 34% chance of being audited). With increases in the rates of tax penalty and audit frequency, people also became more committed to paying their taxes and showed greater compliance.

Maciejovsky et al.’s (2001) experiment was used to inform the design for this follow-up experiment. However, the present study differs in several aspects. Firstly, and most importantly, Maciejovsky et al. (2001) did not present any reference points in tax rate or audit probability in their experiment to their participants. In the current study, it was assumed that presenting a reference point to the participants in tax rate, audit probability and fine rate decisions provides important and precise insights into issues of mental accounting and decision-making. Therefore, the first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1

People treat their labour and capital income differently (evidence of mental accounting) when the tax rate is above the reference point compared with when it is below the reference point.

This hypothesis is 2-tailed because it anticipates 2 possible outcomes regarding how different types of income influence risk behaviour. Firstly, individuals earning labour income, which is typically hard-earned, may exhibit risk-averse behaviour to avoid losing their earnings. Conversely, those with capital income, which might feel more like a windfall, could display risk-seeking behaviour. Alternatively, the hypothesis also considers that labour income earners might view taxes as a loss, prompting risk-seeking behaviour to compensate, while capital income earners might see their earnings as a gain, leading to risk-averse actions. Thus, the hypothesis allows for opposite predictions depending on how income is perceived in terms of loss or gain. Additionally, Maciejovsky et al.’s (2001) experiment was performed about 2 decades ago and in a different setting (American taxpayers). By comparison, the current research experiment uses a different (UK based) sample and differing types of income. The design of the current study presents 2 sources of income as a hard-earned income (labour) and an endowment (capital) to participants and asks them to evaluate their tax declaration decisions based on different rates of taxes, fines and audit probabilities considering a given reference point.

Therefore, the objective of the current study is to investigate whether tax declaration decisions regarding various tax rates, fines, and audit probabilities can be influenced by mental accounting. Additionally, the research seeks to understand the underlying mechanisms driving taxpayer behaviour, particularly in response to rising tax rates, increased fines, and greater audit probabilities. Consequently, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2

with increases in the tax rate, people will declare less income for taxation (to evade tax) from both labour and capital income.

Hypothesis 3

with increases in audit probabilities and fine rates, people will declare more income for taxation (engage in less tax evasion) from both labour and capital income.

Method

This study employed an experimental approach, closely modelled upon previous designs in the context of mental accounting. Our method aligns with the nature of our research question and objectives, aiming to investigate whether tax declaration decisions regarding various tax rates, fines, and audit probabilities can be influenced by mental accounting. Our chosen sample size, validated through a power calculation, is sufficient to detect significant effects as predicted by our hypothesis and aligns with the sizes used in previous studies (e.g., Bornman and Ramutumbu 2019; Iyer and Kaszak 2022). Furthermore, the chosen experimental design was practical and feasible within the constraints of our study. Additionally, the incentives offered to participants, including course credits, free coffee, and entry into a lottery, were carefully selected to encourage participation while mitigating potential recruitment biases.

Participants

A sample of 47 peoples including university staff and students were recruited via an electronic university newsletter. 3 participants were excluded from the main study analysis as their data was not useable due to poor understanding of the task. Therefore, the sample consisted of 44 participants, 21 men and 23 women with a mean age of 29.84 years (SD = 11.06). Participants could choose between receiving course credits (EPR) and a free coffee for participation. Additionally, all participants were entered into a lottery, with an equal chance to win up to £10 if they were 1 of the 5 lucky winners selected in the raffle (the exact amount depended on their decisions in the study, see Procedure for more details). 5 other participants completed a pilot study to check the wording of the materials.

Design

The experiment used a within-subjects design with the conditions presented in a randomized order. The independent variables were: (1) variations in the tax rate, (2) the audit probability, (3) the fine rate, (4) and income sources. For the first 3 variables, participants were told and presented with representative figures (as a reference point) as follows: tax rate: 30%, Audit probability: 3%, fine rate: 1.5 times the amount of evaded tax. In each scenario, we applied a different rate for the independent variable but kept the rate for the other 2 variables constant. In order to investigate and compare decision behaviours, we included levels above and below the representative reference point. The variations in the tax rate had 5 levels: 2 levels were below the reference point for tax rate (5% and 15%), 1 at the reference point (30%) and 2 levels above (45% and 60%). For audit probability we had 3 levels below the reference point included as (0%, 1% and 2%) and 2 levels above the 3% reference point (4% and 5%). Finally for the fine rate we also considered 3 levels below the 1.5 reference point (0 times the amount of evaded tax, 0.5 times and 1 times the amount of evaded tax), and 2 levels above the reference point (2.5 and 3.5 times the amount of evaded tax). The 2 different income sources were defined as labour income and capital income. The labour income was earned on the number of mathematical matrices that participants solved correctly, and the capital income was given as an endowment from the experimenter.

The dependent variable was mean percentage of income declared for tax from the 2 income sources. Both incomes were taxed and there was an opportunity for the participants to choose the amount of income they declared for tax purposes in units of the experimental currency, EC. At the end of the experiment, the experimental currency, EC, was converted into pounds sterling by dividing it by 100. So, for instance, if a participant earned 900 units in the experiment, at the end of the experiment, this income was divided by 100 which equalled 9 pounds sterling.

Materials

The study was conducted in a large computer laboratory. Each participant was seated at a computer desk, with all desks generously spaced out to avoid any communication between participants. All participants received consent forms and an information sheet. Instruction slides were also displayed on their computer screens and participants completed the experiment using z-Tree software (Fischbacher 2007). In the first task, participants were presented with a series of 10 tables with variety of numbers in each table. Tables were presented in a random order to participants, and they were asked to correctly count the sum of numbers in each column.

After gaining the labour income from doing task 1 and gaining the capital income as an endowment from the experimenter, in the second task, participants were presented with a series of tax decision scenarios in a random order based on different rates for tax, fine and audit probability. Then they were asked to specify how much of their income, from each source of income (labour and capital), to declare for tax purposes (declaration decision).

Procedure

Each testing session lasted between 40 and 60 min and in each session, 2–6 participants completed the experiment at the same time. The participants were told not to communicate with each other and to switch off their phones. The experimenter ensured that all participants were focusing on their own computer screens and materials at all times. Each participant filled in the consent form and was briefed individually. Participants were then presented with the computerised instructions and the experimenter encouraged questions at all times and provided answers in private. In addition, prior to the start, the experimenter communicated with each participant to make sure each participant had understood the experiment correctly. First, participants were asked to complete the addition tables in a limited amount of time (90 s for each table). They were incentivised with a payment of 50 experimental currency for each correct table, and this would form their labour income in the later experiment. The capital income was an endowment from the experimenter (525 experimental currency) that was given to all participants.

Participants were told that upon study completion, 1 of their decisions in the experiment would be chosen randomly. The income they had earned in that decision (e.g., their post-tax labour and capital income) would be paid to them if they were 1 of the 5 lucky winners selected in the raffle that all participants were be entered into (up to £10). It was emphasized that every decision they made had an equal chance of being chosen.

Results

Three repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine if the independent variables (1) tax rate (5 levels), (2) audit probability (6 levels), (3) fine rate (6 levels), and (4) source of income (2 levels) had an influence on the dependent variable (amount of declared money to be taxed from each source). The role of gender was examined for potential influence, but no significant main effects or interactions with other variables were found, thus precluding further reporting on this matter.

Tax rate and declaration decision from labour and capital income

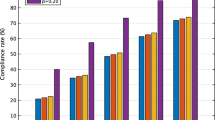

As it can be seen in Fig. 1, the tendency to declare income from labour and capital income resources decreased linearly with increasing tax rate. Notably, a large drop in tax declarations was observed for the 60% tax rate condition in labour income compared to capital income, which indicates that individuals were much less willing to declare tax for labour income when tax rates reached 60% (Table 1).

A 2-way repeated measures ANOVA compared the effect of tax rate variations and income sources on tax declaration decisions. The result showed that the experimental tax rate manipulation had a significant effect, F(4, 172) = 58.20, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.58. The income source had a significant main effect, as individuals declared less of their labour income (M = 64.83%) compared to their capital income (M = 76.30%), F(1, 172) = 72.47, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.63. Additionally, a significant interaction was found between tax rate and source, F(4, 172) = 61.01, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.587. The effects of the source varied depending on the presented tax rate, and post-hoc t-test comparisons showed that the difference in income declared for tax between labour and capital income was only significant (p < 0.001) at the 60% level and not at the lower levels of tax rates.

Audit probability and declaration decision from labour and capital income

To test the effect of audit probability on tax declarations pertaining to labour and capital incomes, we used a 2 × 6 repeated measures design. We conducted the experiment with 2 independent variables of source and audit probability. Figure 2 shows that with an increase in audit probability rate individuals declared more income from their labour and capital income sources. The percentage of declared income rises from around 45% at the 0% audit probability rate to 84% at the 5% audit rate, and percentages are very similar across the 2 sources of income. Indeed, the results of a 2-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of audit probability on participant’s income declaration decision, F(5, 215) = 22.64, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.35, with pairwise comparisons indicating significant differences between all of the different rates of audit probability (all p < 0.05). Participants’ mean income declarations did not differ significantly for labour (M = 68.53%) and capital income (M = 66.38%), F(1, 43) = 0.97, p = 0.33, η2p = 0.02. Furthermore, no significant interaction was found between income source and audit probability F(5, 215) = 0.30, p = 0.91, η2p = 0.01 (Table 2).

Fine rate and declaration decision from labour and capital income

The effects of fine rate and income source were tested using a 6 × 2 repeated measures design. The descriptive results in Fig. 3 shows that as fine rates increased, income declarations for tax purposes increased. The results of the 2-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of fine rates on participants’ tax declaration decision F(5, 215) = 62.28, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.59. Participants declared more income from both their labour and capital resources as the fine rates increased and pairwise comparisons showed significant differences between all different fine rates (all p < 0.05). Our tests of within-subject effects found no significant differences between the labour and capital income, F(1, 43) = 1.89, p = 0.176, η2p = 0.04, but there was a significant interaction between fine rate and income source, F(5,215) = 7.62, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.15. Post-hoc comparisons revealed a difference in income declared between labour and capital income (p < 0.001), but only for a fine rate of 0 when significantly less capital income than labour income was declared (Table 3).

In Table 4, a summary is presented of the experimental findings on tax declaration behaviour. The table highlights the key insights obtained across varying tax rates, audit probabilities, and fine rates. It provides an overview of how these factors influence taxpayer decisions, offering significant understanding into the complexities of tax compliance behaviour observed in the study.

Discussion

This study provided new experimental insights on the effect of mental accounting in tax liabilities. In contrast to previous studies in this field, which typically used questionnaire designs, we presented participants with experimental tasks, in which they could earn money and make monetary decisions based on their income. This represents a novel design in the context of mental accounting research and allowed for controlled analyses of tax declaration decisions across different tax rates, fine rates, audit probabilities and income sources. Furthermore, our design included consideration of reference points in tax liabilities. As discussed in Kahneman and Tversky’s (1979) prospect theory, the evaluation of outcomes is firmly dependant on a reference point, and this can determine whether outcomes are perceived as gains or losses. Based on this assumption, levels below a reference point are considered a loss and levels better than a reference point are considered as gain. We set out to explore the implications of reference points for different tax rates, audit probability and fine rates scenarios, and investigate their potential to affect financial decisions in the context of tax liabilities.

In the first scenario, which involved different tax rate variations, the results showed that participants declared less income for tax from their labour and capital income when tax rates increased. A sharp drop in tax declaration decisions related to labour income was reported when the tax rate rose to the study’s maximum 60%, which was not as pronounced for capital income. Overall, these results show that higher tax rates tempt people to engage in tax evasion. While tax evasion levels were similar across different income sources for tax rates ranging between 5–45%, tax evasion for labour income was significantly larger than for capital income when tax rates rose to 60%. This willingness to cheat in order to protect labour income, suggests that individuals value their earned income more compared to income received from a given endowment (capital income). The results reported here support the study carried out by Ashby and Webley (2008a, 2008b), who also emphasized the role of mental accounting as a determining factor in tax compliance behaviour. They found that some hairdressers or beauticians tend to put their ‘cash in hand’ payments into a separate mental account and spend it as they wish rather than declare it to the tax office.

In another study, Muehlbacher and Kirchler (2013) also found that when individuals are going to pay taxes, they usually experience loss and emotional pain, which may be reduced through tax evasion. They argued that perhaps it will be harder for individuals to pay taxes out of their pocket (gross income) because this is their actual income and they put effort into obtaining it. Therefore, when they mentally separate their tax element from their net income it will be easier for them to pay tax. Reflecting on our sample in this study, the mean age was 29 and we are confident that participants were familiar with paying taxes from their earned incomes. However it occurs to us that older people could have had more exposure to tax payments than younger people and this could be a variable of interest for future research. Also a comparison could be made of people who complete an annual tax return and then pay taxes compared to those from whom taxes are deducted from salary before it is paid to them.

With regard to audit probability rates, our results showed increasing tax declarations with increasing risks of being audited, but no differences were found between the 2 income sources. It thus appeared that participants valued labour and capital incomes similarly and that no mental accounting took place. Maciejovsky et al. (2001) reported similar findings. Their results indicated that decision-makers reported similar tax declaration levels for incomes from selling assets and dividend earnings across 17% and 34% audit probability scenarios. In contrast with the previous research, our experiment included a condition with a 0% audit probability rate to investigate if participants evaded more taxes when they were faced with no audit risk. However, our results indicated that there were significant differences in declarations between all audit rates. While declarations were lowest at the 0% audit rate, they did not reach a level of zero, as might be predicted by rational economic theory. This suggests that psychological factors such as honesty or prosociality may play a role in making tax decisions.

Our last hypothesis investigated whether increments in fine rate had the power to decrease tax evasion and whether participant choices differed between labour and capital income. We did not find a significant difference between choices pertaining to labour and capital income except at a fine rate of 0, where only 25% of capital income was declared compared to 39% of labour income. This effect could be explained as people’s tendency to show some honest behaviour regarding their labour income and declare more of it when there is no fine on their tax declaration decision. By comparison, in the capital income condition, they potentially considered this type of money as a source of windfall and preferred to declare less and keep it when there is no potential fine to pay. Our findings pertaining to fine rates are consistent with the findings of Maciejovsky et al. (2001). They also found that the tax penalty (fine rate) was positively related to tax compliance. However, Maciejovsky et al. (2001) only included a penalty of 50% payment of the evaded income versus a penalty of 100% payment of the evaded income in their study. Therefore, our study was more comprehensive and provided more detailed findings which showed that different fine rates in tax declaration resulted in significant differences of tax compliance. As tax penalty or fine rate increased, participants practiced less tax evasion from both their sources of income.

However, we did not find any evidence for the influence of reference points. Further research is required to test the effects of reference points on mental accounting more closely and assess the strength of their impact within various tax compliance settings. One particular research priority might involve assessing how people adapt their decisions to different reference points during various tax compliance choices and how easily reference points can be manipulated and measured. Additionally, forthcoming studies could expand the scope of tax decisions to encompass a broader array of income types. For instance, considerations could be extended to include windfalls and other sources of income, providing a more comprehensive understanding of tax compliance behaviours.

Taken together, mental accounting has rarely been studied in tax compliance settings (Muehlbacher and Kirchler 2013). The findings from this study make several contributions to the current literature. This study has shown that a decrease in tax rates and increase in audit rates and fine rates reduce socially undesirable behaviours of tax evasion and ensure more tax compliance among decision makers. Furthermore, nuanced effects of mental accounting were seen in the context of tax liabilities. The results of this study indicated that taxpayers might be particularly sensitive to very high tax rates in the context of labour incomes, for which they worked hard.

Conclusion

This study explored how people manage their money when it comes to taxes and within the theoretical framework of mental accounting. It was discovered that as tax rates increased, people tended to declare less of their income, especially the money they earned through hard work (labour income). However, when there was a higher chance of getting audited, people were more likely to report their income, regardless of its source. Furthermore, it was found that when the penalty for not paying taxes increased, people were more inclined to comply with tax regulations by declaring both of their sources of income. Our combined evidence provides initial support for mental accounting in tax liabilities, suggesting that the way individuals perceive tax payments relative to their overall income might influence their tax-related decisions.

Furthermore, while the study investigated tax evasion behaviours across varying tax rates, audit probabilities, and fine rates, it may not cover the entire spectrum of tax evasion strategies observed in real-world settings. Future research could address this limitation by conducting studies in real-world tax settings to observe actual taxpayer behaviour in naturalistic environments. Our findings might be the first step towards informing the design of more effective tax policies and financial education. According to Adams and Webley (2001) in order to increase tax compliance we need to educate taxpayers towards using more appropriate mental accounting strategies. A first step towards improving education is to gain better insights into successful mental accounting processes and to improve our understanding of how these might affect tax choices.

References

Adams G, Webley P (2001) Small business owner’s attitudes on VAT compliance in the UK. J Econ Psychol 22:195–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(01)00029-0

Ashby J, Webley P (2008b) "The trick is to stop thinking of it as ‘your’ money": Mental accounting and taxpaying. Paper presented at the IAREP/SABE world meeting 2008: Economics and psychology: methods and synergies, Rome, http://static.luiss.it/iarep2008/programme/programme3.php? # Paper=l 13

Ashby J, Webley P (2008a) ‘But everyone else is doing it’: a closer look at the occupational taxpaying culture of one business sector. J Communit Appl Soc Psychol 18:194–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.919

Bornman M, Ramutumbu P (2019) A tax compliance risk profile of guesthouse owners in Soweto, South Africa. South Afr J Entrepr Small Bus Manage 11(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v11i1.181

Burt I, Thorne L, Walker JK (2017) Mental accounting and taxpayer compliance: insights into the referent point that separates honest from dishonest behavior (December 25, 2017). Canadian Academic Accounting Association (CAAA) Annual Conference. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3098194

Burt I, Thorne L, Walker J (2023) Reference points, mental accounting, and taxpayer compliance: insights from a field study. In Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp 139–167

Chambers V, Spencer M (2008) Does changing the timing of a yearly individual tax refund change the amount spent vs. saved? J Econ Psychol 29(6):856–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2008.04.001

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4

Hikmah H, Adi PH, Supramono S, Damayanti TW (2021) The nexus between attitude, social norms, intention to comply, financial performance, mental accounting and tax compliance behavior. As Econ Financ Rev 11(12):938–949. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.aefr.2021.1112.938.949

Iyer GS, Kaszak SE (2022) What do taxpayers prefer: lower taxes or a better year-end position? A research note. J Account Public Policy 41(2):106902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2021.106902

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrics 47:263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Kahneman D (2002) Maps of bounded rationality: a perspective on intuitive judgement and choice. https://cmapspublic2.ihmc.us/rid=1JYQGMJ2F-12L12PD-12N9/kahnemann-lecture.pdf

Kirchler E (2007) The economic psychology of tax behaviour. Cambridge University Press

Maciejovsky B, Kirchler E, Schwarzenberger H (2001) Mental accounting and the impact of tax penalty and audit frequency on the declaration of income: An experimental analysis (No. 2001, 16). Discussion papers, Interdisciplinary Research project 373: Quantification and simulation of economic processes.

Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E (2013) Mental accounting of self-employed taxpayers: on the mental segregation of the net income and the tax due. FinanzArchiv/public Financ Anal 69(4):412–438. https://doi.org/10.1628/001522113X675656

Muehlbacher S, Hartl B, Kirchler E (2017) Mental accounting and tax compliance: experimental evidence for the effect of mental segregation of tax due and revenue on compliance. Public Finance Review 45(1):118–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142115602063

Olsen J, Kasper M, Kogler C, Muehlbacher S, Kirchler E (2019) Mental accounting of income tax and value added tax among self-employed business owners. J Econ Psychol 70:125–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2018.12.007

Page L, Savage DA, Torgler B (2014) Variation in risk seeking behaviour following large losses: a natural experiment. Eur Econ Rev 71:121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.04.009

Stearns SC (2000) Daniel Bernoulli (1738): evolution and economics under risk. J Biosci 25(3):221–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02703928

Thaler R (1985) Mental accounting and consumer choice. Mark Sci 4(3):199–214. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.4.3.199

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1985) The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. In: Tversky A, Kahneman D (eds) Behavioral Decision Making. Springer, Boston, MA, pp 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2391-4_2

Webley P, Ashby JS (2010) The economic psychology of value added tax compliance. In: Alm J, Martinez-Vazquez J, Torgler B (eds) Developing Alternative Frameworks for Explaining Tax Compliance. Routledge, Abingdon

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Javareshk, M.B., Pulford, B.D. & Krockow, E.M. Mental accounting in tax liabilities. Decision (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40622-024-00385-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40622-024-00385-0