Abstract

Aims

The aim was to translate and culturally adapt the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 (YFAS 2.0) to the Chilean population, evaluate its psychometric properties in a non-clinical sample, and assess the correlations between symptoms count of food addiction (FA) with demographic and anthropometric variables.

Methods and participants

We evaluated 301 participants (59.1% women) with a mean age of 29.7 ± 12.4 years recruited from two universities and two businesses (non-clinical sample). The Chilean YFAS 2.0 was administered, and anthropometric measurements were carried out. The internal consistency of the items was estimated, and factor structure was tested by confirmatory factor analysis. Test–retest reliability was also examined. The correlations between symptoms count of FA and weight, waist circumference (WC), Body Mass Index (BMI), percentage of body fat (BF%), and lean mass were evaluated.

Results

The Chilean YFAS 2.0 presented good internal consistency, and confirmatory factor analysis supported the one-factor structure, in accordance with the original version. The ICC indicated excellent test–retest reliability. The prevalence of FA was 10.3%, and the symptom count of FA was 2.1 ± 2.8. A small positive correlation between WC, BMI, and BF % and FA symptom count was found.

Conclusion

The Chilean YFAS 2.0 may be a useful tool to investigate FA in Chile.

Level of evidence Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chile is one of the Latin American countries with the highest rates of non-communicable chronic diseases associated with the consumption of foods and beverages high in critical nutrients (salt/sodium, sugar, saturated fats, and trans fats) and sedentary lifestyles, such as hypertension, obesity, or diabetes [1]. These diseases affect the quality of life and life expectancy and are related to health complications and mortality. In addition, they have a high cost of treatment for the health system [2]. There is particular concern about the high levels of overweight/obesity (74% in the adult population) [3]. These data have led to consider obesity a public health problem.

There is evidence that overconsumption of highly processed foods/beverages (i.e., refined carbohydrates and/or added fats), one of the main causes of obesity, could be explained, at least in part, by the presence of food addiction (FA) [4,5,6,7]. The construct of FA refers to the idea that the consumption of hyperpalatable, highly processed foods activate an addiction-like response in vulnerable individuals, which can lead to excessive intake [8, 9]. While FA is not currently recognized as an official diagnosis, the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) operationalizes the construct by applying the substance use disorder diagnostic criteria, from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to the intake of hyperpalatable, highly processed foods [10]. Other versions of the YFAS are available. The modified version of the YFAS (mYFAS) was developed for use in large epidemiologic cohorts by adapting the validated YFAS to a core of 9 questionnaire items [11]. Similarly, the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 (mYFAS 2.0) is an abbreviated, 13-item version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0 (YFAS 2.0) [12]. The modified versions of the YFAS perform similarly on psychometric indicators as the full versions of the scale and are useful brief assessment tools for food addiction. The YFAS 2.0 demonstrates excellent psychometric properties [8] and has been validated in different countries, including Spain, Italy, Denmark, Malaysia, France, Germany, China, and Portugal [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The YFAS 2.0 has not been validated in Chile or other Spanish-speaking Latin American countries.

A strong association between FA as measured by the YFAS and weight status has been reported, with a greater likelihood of FA diagnosis in individuals with obesity [9, 21, 22]. A systematic review indicated that FA prevalence was double in participants with BMI ≥ 25 compared to those with lower BMIs (24.9% and 11.1%, respectively) [23].

Considering the significant public health problem that overweight and obesity represent for Chilean population and the strong association described between FA and obesity [9, 21], the current study aimed to translate the YFAS 2.0 to local Spanish and culturally adapt it to the Chilean population and to evaluate its psychometric properties in a non-clinical sample. In addition, to explore the prevalence of FA and evaluate the associations of FA with demographic and anthropometric variables in a non-clinical sample.

Methods

Procedures

A cross-sectional study was conducted with a non-probabilistic sample in two cities of Chile, from August to October 2022. Students were recruited to participate in a study on the different causes of overweight and obesity from two universities, one in Santiago and one in Valparaíso. In addition, administrative workers were recruited to participate in this study from two companies in Santiago. A total of 301 subjects participated in this non-clinical sample (61.5% students; 38.5% administrative workers). The inclusion criteria were that participants had to be over 18 years of age, who were not on medication for weight loss because of the effects on appetite inhibition. Participants who presented any limitation, either language or cognitive ability, that prevented self-administration of the questionnaire were excluded from the study. In addition, pregnant or breastfeeding women were excluded. The university students were invited to participate while walking near the measurement area installed on both campuses. In the case of companies, human resources departments were contacted, who agreed to set up a room for measurements. They sent an invitation email to their employees. Those who wanted to participate came to the measurement room voluntarily. In both cases, the participants were told that participation in the study was voluntary, without financial compensation, but that they would obtain their anthropometric measurements.

Measures

Participants were asked to provide basic demographic information, including gender, age, education level, employment status, marital status, and if they were currently undergoing psychological treatment. Weight and height were measured using a SECA® brand scale (0.1 kg precision) and a height rod (0.1 cm precision). The nutritional status was determined by calculating the Body Mass Index (BMI). It was classified according to the criteria of the World Health Organization as low weight (BMI ≤ 18.5), normal nutritional status (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), or obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [24]. Waist circumference (WC) was measured using a flexible tape at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the last rib. The participant remained standing with the arms next to the body and the trunk free of clothing. The measurement was made with the abdomen relaxed at the end of expiration [25]. The InBody® Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) was used to measure body composition, determining the percentage of body fat mass (%BF) and fat-free mass (FFM) [26]. Trained and standardized evaluators performed the measurements. The privacy of the participants was protected during the anthropometric measurements.

Translation and adaptation of the YFAS 2.0 for a Chilean population

The YFAS 2.0 is a 35-item self-report scale scored on an eight-level Likert scale (from 0 = never to 7 = every day), designed by Gearhardt et al. [27] to assess FA symptoms over the previous 12 months, based on 11 diagnostic criteria for substance-related and addictive disorders proposed in the DSM-5 [10]. These scores produce two measurements: (a) a continuous symptoms count score that reflects the number of fulfilled diagnostic criteria (ranging from 0 to 11) and (b) a food addiction threshold based on the number of symptoms (at least 2) and self-reported clinically significant impairment or distress. This final measurement allows the dichotomous classification of FA (FA vs No FA). Based on the revised DSM-5 taxonomy, the YFAS 2.0 also provides severity cutoffs for patients surpassing the threshold for food addiction: mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), and severe (6–11 symptoms).

The YFAS 2.0 translation and culturally adapted procedure was conducted by the primary author. The translation was conceptual and not literal. The language used was natural and acceptable to be understood by Chilean adults. The blind back translation was performed to verify conceptual equivalence between the translated version and the original scale. This process was carried out by a bilingual professional with excellent command of the Spanish language but a native English speaker. To reduce information bias, the professional had no prior knowledge of the scale. Subsequently, an independent professional, native English speaker and fluent in Spanish, verified the similarity between the reverse translation and the original English version. A comparison was then made between the two versions. In this process, some differences were found in the use of the past tense. A judgment was carried out by a panel of five experts (three clinical psychologists who work in eating disorders, a psychologist PhD in Population Health, and a nutritionist specializing in eating disorders in adults). The objective of the panel was to detect expressions or concepts that were not appropriate for understanding the scale and to detect any discrepancy between the original scale and the translated one. Small modifications were introduced mainly in the verb tenses of some items. Then, a pilot test of the scale translated into Chilean Spanish was carried out in a convenience sample of 15 adults with different educational levels. Participants completed the scale in approximately 9 min. According to this administration, the wording of the three questions #6, #11, and #14 caused comprehension difficulties and were revised for clarity. Two adjacent questions had very similar content (#31: I tried to reduce or not eat certain types of foods but was unsuccessful; and #32: I tried and failed to reduce or stop eating certain types of foods), which caused confusion. Therefore, the order of these questions was altered so that they were not asked immediately after each other. The final Chilean YFAS 2.0 maintained the 35 questions of the original YFAS 2.0 (see Supplementary material).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) and MPlus software (Muthén & Muthén version 8, April 2017, CA.USA) for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The distribution of quantitative variables was evaluated by histograms and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. The sample characteristics were represented with absolute values, percentages for qualitative variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables.

As in the original article, clinically significant impairment/distress was not included in the psychometric properties and factor structure analysis as they reflect clinical significance of the full syndrome rather than indicators of individual criteria [27]. CFA was conducted based on the tetrachoric correlations among the 11 diagnostic criteria to compare a 1-factor and a 2-factor (dependence and abuse) model. The comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were used to evaluate the model. Given that all items were dichotomous, Kuder–Richardson alpha (KR-20) and McDonald’s ω [28] were used to assess the internal consistency of the Chilean version of YFAS 2.0. The following cutoffs were used as indicators of excellent validity and reliability of the psychometric model: KR-20 internal reliability coefficient > 0.7, McDonald’s ω > 0.7, CFI > 0.90, TLI > 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.08 [29, 30].

To evaluate the test–retest reliability of the Chilean YFAS 2.0 the scale was administered 7 to 10 days apart between the first and second application. The 88 participants who answered the retest corresponded to 29% of the sample. Of these participants, 63.6% were female, students (62.5%), single (90.0%), obese (22.7%), and 6.8% had FA in the first application. There were no significant differences in the variables of interest in this study between participants who responded to the retest and those who did not respond (all p values > 0.05). The test–retest correlation coefficient (intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC) was used to evaluate the test–retest reliability. The values of ICC were interpreted as follows: > 0.75 was excellent, between 0.40 and 0.75 was fair to good, and < 0.40 was poor. To detect demographic differences, anthropometric and body composition measurements between the subjects with or without FA, χ2, Fisher's Exact, or T-Student test was used, depending on the type of variable. Spearman correlations between symptom count of FA and anthropometric and body composition measurements were evaluated.

Ethics

The study protocol followed the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad del Desarrollo—Facultad de Medicina–CAS. All participants provided electronic informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

In our study, the largest proportion of participants were female (59%), mainly university students (87%), and single (85%). The median age was 29.7 ± 12.4. More than 50% of the sample was in a weight status of overweight or obese. Other demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1.

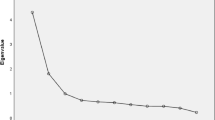

Table 2 shows a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the Chilean version of YFAS 2.0 in a non-clinical sample. The 1-factor model had adequate fit indices where CFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.985, SRMR = 0.063, RMSEA = 0.040, with all factor loadings greater than 0.69. Consistently with the YFAS 2.0 validation study (25), we retained a 1-factor solution because the 2-factor model did not result in a markedly improved fit (CFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.984, SRMR = 0.062, RMSEA = 0.041). In addition, factor 1 and factor 2 in the 2-factor model were highly correlated (r = 0.96, p < 0.001). The Kuder–Richardson alpha for the unidimensional model was 0.85, and McDonald’s ω was 0.88, which suggested satisfactory internal consistency reliability, and the ICC (0.96) for the test–retest of the Yale 2.0 Chilean version was excellent.

The prevalence of FA was 10.3%, and the median symptom count was 2.1 ± 2.8. Regarding the severity of FA, 0.3% met the mild criteria, 2.0% met the moderate criteria, and 8.0% met the severe threshold. The most frequently reported symptoms were: 28.2% “consumed food in larger quantities or for a longer period than planned”; 27.9% “withdrawal”; and 24.3% “persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control consumption of certain foods” (Table 3).

Table 4 shows demographic and anthropometric characteristics according to No FA or FA. There were no significant differences in any demographic or anthropometric variables by FA status.

There were no significant differences between the symptom count and demographic characteristics, but there was a significant difference (p < 0.001) according to weight status, with individuals with obesity having higher FA symptoms than individuals with either normal or overweight (Table 5).

A small significant (p < 0.05) correlation was observed between symptoms count and WC (rho = 0.12), BMI (rho = 0.15), and BF % (rho = 0.17) (Table 6).

Discussion

The construct of FA indicates that certain foods (hyperpalatable, highly processed, foods) may have an addictive potential, similar to addictive substances like drugs and alcohol [31]. The YFAS 2.0 is a widely used validated measure to evaluate FA based on the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders [27] and it has been adapted for dozens of other languages and cultures [32]. However, no Chilean version currently exists despite rising rates of obesity and diet-related diseases in the country [3]. To develop a Chilean version of the YFAS 2.0, a strict process of translation, back translation, expert judgment, and piloting was carried out and modifications were made to culturally adapt the scale. In a non-clinical sample, the Chilean version of YFAS 2.0 exhibited good psychometric properties comparable to those obtained in the validation of the original version of the YFAS 2.0 [27]. Specifically, the Chilean YFAS 2.0 had good internal reliability, excellent test–retest reliability, and a single-factor model was supported, which is consistent with the results from validation studies of other language versions of the YFAS 2.0 [13, 17, 33].

In our non-clinical sample, the prevalence of FA was 10.3%, which is similar to the prevalence from other non-clinical samples around the world. For example, 10.0% in the validation study of the German version of YFAS 2.0 (10.0%) [18], 10.3% of Canadian university students [34], and 11.4% in undergraduate participants of a private university in the original study of YFAS [8]. This result is also similar to the prevalence of 14.0% found in non-clinical samples based on a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [32].

The most endorsed FA symptoms were “food consumed in larger quantities or over a longer period than intended”, “withdrawal” and “persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control consumption of certain foods”. The first most endorsed symptom, “food consumed in larger quantities or over a longer period than intended”, refers to consumed more than planned or loss of control [10], which is often the most reported symptom in the FA literature [15, 17, 35]. Loss of control over intake is a relevant mechanism in both substances use disorders and eating-related problems [10], such as binge eating [36]. The second most endorsed symptom, “withdrawal”, refers to characteristic withdrawal symptoms (i.e., negative emotional experiences such as irritability or physical experiences such as headaches after the substance is removed from the system); or substance taken to relieve withdrawal [10]. This symptom was the most endorsed in the original validation study (29.7%) [27] and in a sample of Italian general population (12.5%) [14]. Withdrawal in the context of highly processed food consumption has been less studied than in addictive drugs use and may be an important area for future research with clinical relevance. The third most endorsed symptom, “persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control the consumption of certain foods”, refers to an inability to cut down or stop [10]. This symptom was endorsed by 25.0% of the sample in the original YFAS 2.0 validation study [27]. This symptom is also common in eating-related problems, and it could be triggered by the availability of hyperpalatable highly processed foods [37].

Our study did not find differences in weight status by FA diagnosis. Individual’s BMI also did not differ by FA diagnosis. Previous literature presents mixed results. Some cross-sectional design studies have reported that the likelihood of FA in participants with obesity is higher than in normal-weight participants [38,39,40]. In contrast, other studies do not observe these differences by weight status [33, 41]. However, there were differences in the FA symptoms count score by weight status. Specifically, individuals with obesity had higher FA symptoms on the Chilean YFAS 2.0 than individuals with overweight or normal-weight status. The FA symptoms count was also positively associated with BMI. Similar results have been reported in the literature [14, 17, 20, 38, 42, 43]. In the current study, the FA symptoms count (relative to the diagnostic scoring option) was more strongly associated with differences in weight status and BMI. It will be important to investigate differences between the two FA scoring options in clinical samples where FA diagnosis and obesity may both be more prevalent. However, the current study suggests that individuals with obesity are more likely to experience symptoms of addiction related to their food intake, which has been associated with poorer quality of life, deficit in emotional regulation [44] and a poorer response to behavioral weight-loss treatment [45]. Future research is needed to see if these associations are also present and clinically relevant in Chilean participants with different characteristics.

The FA symptoms had a positive small correlation with WC and BF%. Our study is the second one, to our knowledge, to investigate the correlation between FA symptom counts with WC, and BF%. In a non-clinical Canadian sample, FA symptoms were significantly correlated with all obesity-related measurements including body weight, waist and hip circumferences, BF%, and trunk fat percentage determined by DXA [46]. This finding has clinical relevance since it provides evidence of an association between FA symptoms and the cardiovascular and metabolic risk associated with fat accumulation at abdominal level, as well as whole body composition [47]. This is also relevant given that elevated WC has clinical significance in predicting mortality risk beyond BMI [48].

Strengths and limitations

Our results should be interpreted taking into account the following limitations. First, the limitations of cross-sectional studies do not allow us to make causal inferences. Second, a convenience non-clinical sample was used and future validation in clinical samples and nationally representative samples are needed to test the generalizability of the findings. However, the current study provides important evidence on the strong psychometric properties of the Chilean YFAS 2.0, to set the foundation for that research. Third, the YFAS 2.0 has commonly been validated against other psychological measures of compulsive eating, but those have not been validated in Chilean population and this will be an important knowledge gap to fill. Fourth, in the current study we do not have participants with potential eating disorder diagnosis. Prior research has found that FA is related to, but distinct from existing eating disorders [49]. However, future research investigating the overlap between FA and eating disorders in Chilean samples will be important.

What is already known on this subject?

FA refers to a condition characterized by addiction in relation to some high-fat and refined carbohydrate foods. Assessed through YFAS 2.0, FA it is associated with reward-related neural dysfunctions, impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and poor physical and mental health, which validates its clinical relevance.

What does this study adds?

To our knowledge, this is the first study that validates the YFAS 2.0 in the Chilean population. The Chilean version of the YFAS 2.0 has good psychometric properties and is therefore valid for use in food addiction research in the Chilean population. The use of this instrument would provide more evidence of AF in the Chilean population and thus identify individuals who could require targeted treatment for this condition.

Conclusion

Developing countries, like Chile, are in a period of fast transition in their food environment with a prompt increase in the availability and accessibility of hyperpalatable and highly processed foods that may have an addictive potential. However, until now, there were no tools to study the presence of FA in Chile. The current study showed that the Chilean YFAS 2.0 has adequate psychometric properties, which provides an important tool to advance the research of FA at a crucial time in Chile. Future studies should test the validity of the Chilean version of YFAS 2.0 in a clinical sample, which could experience more significant deterioration in their health related to FA. Furthermore, this study is the first to report prevalence of FA in a non-clinical sample of the Chilean population using YFAS 2.0 and is the second to report a correlation between the number of symptoms and fat accumulation at abdominal level, as well as at global body level. These findings suggest the importance of future research into FA and cardiometabolic health.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.The data used in this article is available upon reasonable request directed to the corresponding author

References

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Obesity Update. 2017. https://www.oecd.org/health/obesity-update.htm. Accessed 21 Oct 2022.

Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D et al (2020) Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 192(31):E875–E891

Ministry of Health of Chile. Department of epidemiology. Health planning division. Sub-secretariat of Public Health. National Health Survey 2016–2017. Available on: https://minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ENS-2016-17_PRIMEROS-RESULTADOS.pdf. Accessed 25 Oct 2020.

Barry D, Clarke M, Petry NM (2009) Obesity and its relationship to addictions: is overeating a form of addictive behavior? Am J Addict 18(6):439–451

Gearhardt AN, Grilo CM, DiLeone RJ, Brownell KD, Potenza MN (2011) Can food be addictive? Public Health Policy Impl Add 106(7):1208–1212

Wilson GT (2010) Eating disorders, obesity and addiction. Eur Eat Disord Rev 18(5):341–351

Lerma-Cabrera JM, Carvajal F, Lopez-Legarrea P (2016) Food addiction as a new piece of the obesity framework. Nutr J 15:5

Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD (2009) Preliminary validation of the Yale food addiction scale. Appetite 52(2):430–436

Davis C, Curtis C, Levitan RD, Carter JC, Kaplan AS, Kennedy JL (2011) Evidence that “food addiction” is a valid phenotype of obesity. Appetite 57(3):711–717

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, D.C, American Psychiatric Association

Flint AJ, Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD, Field AE, Rimm EB (2014) Food-addiction scale measurement in 2 cohorts of middle-aged and older women. Am J Clin Nutr 99(3):578–586

Schulte EM, Gearhardt AN (2017) Development of the modified Yale food addiction scale version 2.0. Eur Eat Disord Rev 25(4):302–308

Granero R, Jiménez-Murcia S, Gearhardt AN, Agüera Z, Aymamí N, Gómez-Peña M et al (2018) Validation of the Spanish version of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 (YFAS 2.0) and clinical correlates in a sample of eating disorder. Gambling Dis Healthy Cont Partic Front Psyc 9:208

Manzoni GM, Rossi A, Pietrabissa G, Mannarini S, Fabbricatore M, Imperatori C et al (2021) Structural validity, measurement invariance, reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the Italian version of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 in patients with severe obesity and the general population. Eat Weight Disord 26(1):345–366

Horsager C, Færk E, Lauritsen MB, Østergaard SD (2020) Validation of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 and estimation of the population prevalence of food addiction. Clin Nutr 39(9):2917–2928

Swarna Nantha Y, Kalasivan A, Ponnusamy Pillai M, Suppiah P, Md Sharif S, Krishnan SG et al (2020) The validation of the Malay Yale food addiction scale 2.0.: factor structure, item analysis and model fit. Public Health Nutr 23(3):402–409

Brunault P, Courtois R, Gearhardt AN, Gaillard P, Journiac K, Cathelain S et al (2017) Validation of the French version of the dsm-5 Yale food addiction scale in a nonclinical sample. Can J Psychiatry 62(3):199–210

Meule A, Müller A, Gearhardt AN, Blechert J (2017) German version of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0: Prevalence and correlates of “food addiction” in students and obese individuals. Appetite 115:54–61

Zhang H, Tong T, Gao Y, Liang CG, Yu HT, Li SS et al (2021) Translation of the Chinese version of the modified Yale food addiction scale 2.0 and its validation among college students. J Eat Dis 9(1):13

Gonçalves S, Moreira CS, Machado BC, Bastos B, Vieira AI (2022) Psychometric properties and convergent and divergent validity of the Portuguese Yale food addiction scale 2.0 (P-YFAS 2.0). Eat Weight Disord 27(2):791–801

Gearhardt AN, Boswell RG, White MA (2014) The association of “food addiction” with disordered eating and body mass index. Eat Behav 15(3):427–433

Romero-Blanco C, Hernandez-Martinez A, Parra-Fernandez ML, Onieva-Zafra MD, Prado-Laguna MD, Rodriguez-Almagro J (2021) Food addiction and lifestyle habits among university students. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041352

Pursey KM, Stanwell P, Gearhardt AN, Collins CE, Burrows TL (2014) The prevalence of food addiction as assessed by the Yale food addiction scale: a systematic review. Nutrients 6(10):4552–4590

CDC. Center for diseases control and prevention. Healthy, weight, nutrition, and physical activity. About Adult BMI.. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html. Accessed 29 Sep 2021.

CDC. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). Anthropometry Procedures Manual. 2007. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar 2022.

Inbody H20B User Manual. 2020. https://www.manualslib.com/manual/2849057/Inbody-H20b.html. Accessed 20 Mar 2022.

Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD (2016) Development of the Yale food addiction scale version 2.0. Psychol Addict Behav 30(1):113–121

Green SB, Yang Y (2009) Reliability of summed item scores using structural equation modeling: an alternative to coefficient alpha. Psychometrika 74(1):155–167

Lt Hu, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Mod A Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55

Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V (2014) From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol 105(3):399–412

Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN (2015) Which foods may be addictive? the roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS ONE 10(2):e0117959

Praxedes DRS, Silva-Júnior AE, Macena ML, Oliveira AD, Cardoso KS, Nunes LO et al (2022) Prevalence of food addiction determined by the Yale food addiction scale and associated factors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Eat Disord Rev 30(2):85–95

Khine MT, Ota A, Gearhardt AN, Fujisawa A, Morita M, Minagawa A et al (2019) Validation of the Japanese version of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 (J-YFAS 2.0). Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030687

Lacroix E, von Ranson KM (2021) Prevalence of social, cognitive, and emotional impairment among individuals with food addiction. Eat Weight Disord 26(4):1253–1258

Hauck C, Weiß A, Schulte EM, Meule A, Ellrott T (2017) Prevalence of “food addiction” as measured with the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 in a representative German sample and its association with sex. Age Weight Categ Obes Facts 10(1):12–24

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE (2008) Loss of control is central to psychological disturbance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity 16(3):608–614

Ayton A, Ibrahim A (2020) The Western diet: a blind spot of eating disorder research?-a narrative review and recommendations for treatment and research. Nutr Rev 78(7):579–596

Yu Z, Indelicato NA, Fuglestad P, Tan M, Bane L, Stice C (2018) Sex differences in disordered eating and food addiction among college students. Appetite 129:12–18

Moghaddam SAP, Amiri P, Saidpour A, Hosseinzadeh N, Abolhasani M, Ghorbani A (2019) The prevalence of food addiction and its associations with plasma oxytocin level and anthropometric and dietary measurements in Iranian women with obesity. Peptides 122:170151

Bourdier L, Fatseas M, Maria AS, Carre A, Berthoz S (2020) The psycho-affective roots of obesity: results from a French study in the general population. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12102962

Koball AM, Borgert AJ, Kallies KJ, Grothe K, Ames G, Gearhardt AN (2021) Validation of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 in patients seeking bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 31(4):1533–1540

Rostanzo E, Aloisi AM (2022) Food addiction assessment in a nonclinical sample of the Italian population. Eur J Clin Nutr 76(3):477–481

Şengör G, Gezer C (2019) Food addiction and its relationship with disordered eating behaviours and obesity. Eat Weight Disord 24(6):1031–1039

Minhas M, Murphy CM, Balodis IM, Samokhvalov AV, MacKillop J (2021) Food addiction in a large community sample of Canadian adults: prevalence and relationship with obesity, body composition, quality of life and impulsivity. Addiction 116(10):2870–2879

Fielding-Singh P, Patel ML, King AC, Gardner CD (2019) Baseline psychosocial and demographic factors associated with study attrition and 12-month weight gain in the DIETFITS trial. Obesity 27(12):1997–2004

Pedram P, Wadden D, Amini P, Gulliver W, Randell E, Cahill F et al (2013) Food addiction: its prevalence and significant association with obesity in the general population. PLoS ONE 8(9):e74832

Frank AP, de Souza SR, Palmer BF, Clegg DJ (2019) Determinants of body fat distribution in humans may provide insight about obesity-related health risks. J Lipid Res 60(10):1710–1719

Staiano AE, Reeder BA, Elliott S, Joffres MR, Pahwa P, Kirkland SA et al (2012) Body mass index versus waist circumference as predictors of mortality in Canadian adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 36(11):1450–1454

LaFata EM, Gearhardt AN (2022) Ultra-processed food addiction: an epidemic? Psychothera Psychosom. https://doi.org/10.1159/000527322

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Cecilia Barros, Viviana Assadi, Miguel Cordero Vega, Magdalena Farías, and Gonzalo Ríos for their valuable contribution to the expert judgment process for this validation process. Thank the undergraduate students Macarena Jorquera, Renata De Martino, Sofía Dabovich, Edith Arancibia, Martina Fernández, Diomar Mancilla, and Katherine Medina for their help collecting university data. Special thanks to the Instituto de Ciencias e Innovación en Medicina (ICIM) of the Facultad de Medicina-CAS of the Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile, for the access to use the REDCap platform to collect and store the data.

Funding

This research was funded by Scholarship Leading to Degree from the Universidad del Desarrollo, and Scholarship Program/Doctorado Nacional # 21211599 from National Agency for Research and Development (ANID). This work was supported by the Centro de Micro-Bioinnovación, grant DIUV-CIDI 15/2024, Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, XDT; Writing—original draft preparation, XDT, AP; Methodology, XDT, ANG; Data collection, XDT, AP, CV; Formal analysis, XDT, AV, ANG, and Funding acquisition, XDT.; Writing—review and editing, XDT, AP, CV, AV, ANG.; All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Also, all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad del Desarrollo—Facultad de Medicina–CAS (record number 2022/65, dated August 23, 2022).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Díaz-Torrente, X., Palacio, A., Valenzuela, C. et al. Validation of the Chilean version of the Yale food addiction scale 2.0 in a non-clinical sample. Eat Weight Disord 29, 62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01691-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01691-3