Abstract

Play-based interventions are gaining popularity amongst autistic children. Parents are uniquely placed to deliver these interventions as they are most familiar with their child’s strengths and challenges. Accordingly, reporting the effectiveness of play-based interventions and/or parent-delivered or mediated early-year interventions have been popular topics in the literature in the last decade. Despite this, little is known about the efficacy of parent-mediated play-based interventions on the developmental outcomes of autistic children. To close this gap in knowledge, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and quasi-experiments focusing on social communication skills, language skills, and autistic characteristics of preschool autistic children (0–6-year-old) in non-educational settings. Overall, 26 studies met the inclusion criteria 21 of which were included in the synthesis. Of the included studies, 20 studies reported social communication skills, 15 studies reported language skills, and 12 studies reported autistic characteristics. Pooling effect sizes across the included studies showed that parent-mediated play-based interventions were effective on social communication (d = .63) and language skills (d = .40) as well as autistic characteristics (d = − .19) of preschool autistic children. Our findings suggest that parent-mediated play-based interventions hold promise for improving social functioning and related autistic characteristics for preschool autistic children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by differences in social communication and interaction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Globally, approximately 1% of children have an autism diagnosis (Zeidan et al., 2022) but actual prevalence rates are likely to be higher (Maenner et al., 2021). Autistic children have poorer social communication and language skills compared to their neurotypical peers, which often start to manifest in early childhood with autistic characteristics being observed in children from as young as 6 to 18 months (Kjelgaard and Tager-Flusberg, 2001; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2009; Tanner & Dounavi, 2021; Volkmar et al., 2004). During this period, children usually spend considerable time with their parents or caregivers and engage in playful interactions with objects or people in their surroundings. Although playful interactions may present differently for autistic children, play is widely recognised as an effective medium for scaffolding the development of autistic children’s social communication and language skills through parent–child interactions (Kuhaneck, et al., 2020). Many parent-mediated interventions are designed using play as their delivery framework to teach important skills to autistic children. Though, the efficacy of such interventions on the developmental skills of autistic children has somewhat stayed ambiguous. In this study, we looked to see whether parental involvement in play-based interventions is effective in improving social communication and language skills of autistic preschoolers.

Social communication and language skills refer to a broad range of interrelated skills. Children need to master social communication skills (e.g., joint attention, social anticipation, eye contact, imitation) in order to engage in social interactions with others. Such social communication skills are distinct from language skills (e.g., receptive language, vocabulary knowledge, language production) as they go beyond knowledge and the use of oral language. Instead, social communication requires an intention to use language or non-verbal skills to engage with another person. To this end, as a group, autistic children tend to have poorer social communication and language skills compared to neurotypical children (Wetherby et al., 2007). There are, however, considerable individual differences in the manifestation (Swineford et al., 2014) and onset (Landa & Garrett-Mayer, 2006) of social communication and language impairments in autistic children.

With the onset of early identification and diagnosis of autism, early interventions are recommended to increase a child’s potential to achieve optimal developmental outcomes (Tanner and Dounavi, 2021). The realisation that parents can play a critical role in delivering therapeutic programmes resulted in the popular parent-mediated interventions which involves training parents as “therapists” to work with their young children at home (Oono et al., 2013). The goal of a parenting intervention is to improve caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes, practices, and skills in order to promote optimal early child development (Jeong, et al., 2021). It involves an intentional mediator who provides instruction, as well as creates conditions for generalisation and transfer of the learning experience to individuals whose capacity to benefit from formal and informal learning is restricted (Feuerstein, et al., 1991). Parent-mediated interventions may employ principles of mediated learning where a dynamic interaction is facilitated between the mediator, the participant, and the stimuli or environment — the parent/caregiver, the autistic child, and the intervention activities, respectively (Feuerstein, et al., 1991). However, not all parenting interventions fully apply principles of mediated learning as seen in the differences between parent-implemented and mediated interventions and evidenced by strategies such as modelling or reinforcement to promote direction-following versus supporting socially motivated communication on the child’s own volition (Schertz et al., 2022). Training parents as interventionists allows intervention to begin early, with the aim that parent–child interaction strategies help enhance autistic children’s earliest social relationships, communication, language, and behaviours.

Play is an indispensable activity in children’s lives as it contributes to many areas of child development including cognitive, social communication, language, emotional, and physical development. For instance, it has been suggested that symbolic play is effective in supporting perspective-taking (Bergen, 2002), representational understanding (Vygotsky, 1967), and theory of mind skills (Lillard & Kavanaugh, 2014). Play is instrumental in supporting children’s social communication skills (So et al., 2020; Goods et al., 2013; Shire et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2018; Stagnitti et al., 2012) and language skills (Craig-Unkefer & Kaiser, 2002; Danger & Landreth, 2005; Han et al., 2010; Quinn et al., 2018). Therefore, play-based interventions have been commonly used to improve the developmental skills of autistic children. (Dijkstra-de Neijs et al., 2021; Gibson et.al., 2021; Kent et al., 2020; López-Nieto et al., 2022; Waddington et al., 2021). Some commonly applied play-based interventions include Joint Attention Symbolic Play Engagement and Regulation (JASPER; Goods et al., 2013), Developmental, Individual-differences, Relationship-based model (DIR/Floortime; Mercer, 2017), and Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT; Ona, et al., 2020; Verschuur, et al., 2014). Several other—validated or non-validated—play-based interventions have been used to improve quality of life for autistic children (e.g., Kasari et al., 2010; Schertz et al., 2013).

A high volume of systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses have been published in recent years about both parent-mediated early interventions (e.g., Althoff et al., 2019; Beaudoin et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2023; Conrad et al., 2021; Naveed et al., 2019; Nevill et al., 2018; Shalev et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2018; Trembath et al., 2019) and play-based interventions (e.g., Dijkstra-de Neijs et al., 2021; Gibson et al., 2021; Kent et al., 2020; López-Nieto et al., 2022; Tachibana, et al., 2017; Waddington et al., 2021). To date, no review has so far been focused expressly on the efficacy of parent-mediated play-based interventions on the developmental outcomes of autistic children. A few of the most recent systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses are discussed based on relevance to this paper, i.e., assessed the effect of parent-mediated and/or play-based interventions on outcomes relating to autism characteristics including social communication and language skills in preschool years. See Supplementary Table 3 for a summary of a selection of relevant recent reviews and/or meta-analyses and how each differs from the current review.

The Current Study

There are two common limitations of previously published reviews on parent-mediated early interventions and play-based interventions in this field. First, the inclusion of a variety of intervention types makes it difficult to find a common ground for effective interventions. Second, the focus on reporting the developmental outcomes of participants from a wide age range (i.e., early childhood to late adolescence) limits our understanding of how effective those interventions are in certain developmental stages. For example, Cheng et al. (2023) found an overall favourable intervention effect for social skills, language skills, maladaptive behaviours, and adaptive behaviours of autistic children aged 2 to 11 years, though they acknowledged the wide variety of interventions as a limitation. Similarly, Conrad et al. (2021) reported a significant early intervention effect on adaptive functioning, but not autism severity, for autistic children aged 1 to 17 years. However, the authors did not report whether the type of intervention was a moderating factor on the efficacy of the included trials. In another example, Naveed et al., (2019) reported significant intervention effects on various developmental outcomes of autistic children aged 2 to 17 years such as social communication skills, expressive language, joint engagement, motor skills, repetitive behaviours, self-regulation, and autism symptom severity. Though this review also reported a wide range of different types of interventions only half of which were parent-mediated interventions. Hence, previous reviews of parent-mediated early interventions as well as play-based interventions give no information regarding the efficacy of interventions that are based on a common ground—i.e., play—on the developmental needs of autistic children at a specific developmental stage.

To overcome this, we systematically screened studies (published or unpublished) reporting the efficacy of parent-mediated, play-based interventions on the social communication and language skills of autistic children. Our review focused on preschool ages (0–6 years), and we were specifically interested in interventions that were implemented in non-educational settings, to control for school-related effects’ on child-level outcomes. In doing this, we addressed the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the key characteristics of parent-mediated play-based interventions?

-

2.

How effective are parent-mediated play-based interventions in improving social communication and language skills and reducing autistic characteristics?

-

3.

What factors, if any, moderate the impact of parent-mediated play-based interventions on social communication and language skills as well as autistic characteristics?

Methods

Review Registration

The current review was designed following the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P, Shamseer et al., 2015) and pre-registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; Ref: CRD42022302220). Additionally, the design, statistical analyses, and reporting of the outcomes of the current review were based on an a priori study protocol published elsewhere (Deniz et al., 2022).

Study Design

The current review focused on locating studies that applied randomised controlled trials or quasi-experimental designs with at least one (i) non-intervention control group, with or without waitlist design, or (ii) control group that received intervention other than play-based.

Target Sample

We searched and screened for studies that focused on preschool autistic children aged 72 months old or younger. A formal autism diagnosis or the use of validated autism screening measures was defined as an inclusion criterion to make sure research participants were autistic.

Intervention Characteristics

The current review included evaluations of parent-mediated play-based interventions that were conducted in non-educational (e.g., home, clinics) settings and targeted social communication and language needs of preschool autistic children. Studies that did not report any information regarding the intervention setting were treated as conducted in a non-educational setting and included in the review as long as they were not delivered or mediated by teachers. Additionally, taking Rubin et al.’s (1983) play approach into account, studies that delivered interventions that were not solely based on play, delivered during playtime or within the playground were excluded from this review. The latter criterion was met in the following conditions:

-

I.

The intervention is a known and named play-based intervention (e.g., JASPER, PLAY).

-

II.

The intervention is a known and named therapeutic approach that uses play as a therapeutic tool (e.g., play therapy, child-centred play therapy, cognitive behavioural play therapy, Rogerian play).

-

III.

The intervention is a known and named developmental intervention that is built on the elements of play or consists of play-based activities such as joint attention, joint engagement, and parent–child play (DIR Floortime, Pivotal Response Treatment, Early Start Denver Model, etc.).

-

IV.

The intervention is not a previously validated intervention but is judged as a play-based intervention by the authors based on the characteristics of the intervention.

The last criterion was met if “play was explicitly mentioned” (Gibson et al., 2021) or if the intervention consisted of parent–child play or child-led play activities. Any interventions that did not meet the above-mentioned criteria were judged as not play-based (e.g., behavioural modification techniques, teaching and training activities, gaming) and were excluded from the current review. Accordingly, studies that delivered the following interventions were excluded from the review at the title or abstract screening stages: video modelling, video prompting, activity schedules, script fading, behavioural interventions, music therapy, virtual reality, gaming, and computer/video games, and tablet applications.

Predictor Variables

The predictor variables were parent-mediated play-based interventions that targeted social communication and language outcomes of preschool autistic children.

Outcome Variables

Initially, we set two target outcomes to report which were children’s social communication (e.g., child-parent interactions, child-peer interactions, joint attention, joint engagement, joint interest, play skills, eye contact, social responsiveness, positive social interaction, initiation of social interaction, child’s social functioning) and language skills (e.g., expressive and receptive language skills, vocabulary, the number of spoken words, the mean length of utterance). However, as we carried along with our review, it came to our attention that most researchers also reported the autistic characteristics of their samples as either a primary or secondary outcome. Therefore, we chose to report autistic characteristics if it was a target outcome in the included studies.

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following criteria were pre-defined for the inclusion of the studies during the title and abstract screening phases:

-

I.

Studies targeting preschool autistic children aged 6 years old (72 months) or younger.

-

II.

Studies with a sample of autistic children, including the ones who screened as “high likelihood for autism” on a validated autism screening measure.

-

III.

Studies that were conducted in non-educational settings (e.g., home, nursery, clinic).

-

IV.

Studies with randomised controlled trial (RCT) or quasi-experimental (QE) designs.

-

V.

Studies that delivered a play-based intervention and used parents/carers as mediators

-

VI.

Studies that are primarily focused on social communication and language outcomes.

-

VII.

Studies published between 2000 and 2023, including grey literature.

-

VIII.

Studies that are published in English.

Additionally, the following exclusion criteria were applied at the full-text screening stage:

-

I.

Pre-experimental studies with no control groups were excluded.

-

II.

Studies that compared the effectiveness of two or more play-based interventions were excluded unless they provided a control group that received a non-play-based intervention.

-

III.

Studies that delivered a play-based intervention that does not meet the concept of play, which is defined in the current review, were excluded.

-

IV.

Studies were excluded if there were multiple implementers in a single intervention group (e.g., intervention group = parent and sibling-mediated play intervention).

Study Selection Procedure

We carried out a systematic review guided by Cochrane (Higgins et al., 2019) and PRISMA-P (Shamseer et al., 2015). A systematic database search was conducted by the first author (ED) on studies published between 2000 and 2023 on the following databases: Ebscohost (including ERIC), ProQuest, PsycINFO, Pubmed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The following predefined search strings were used to capture the relevant studies that met the inclusion criteria: “Autis*,Footnote 1” “Play,” “Social,” “Language,” “Communication,” “Parent,” “Mother,” “Father,” “Carer,” “Caregiver,” “Peer,” “Joint,” “Engage*,” “Eye,” and “Recipr*.” In addition to the master terms, Boolean search strategies were also adopted by combining those pre-specified master keywords with useful operators such as “AND,” “OR,” “NOT,” “*,” and “quotation marks. Details of the use of Boolean operators with the aforementioned search terms can be found in supplementary materials. In addition, a comprehensive citation search was undertaken by the first (ED) and second (GF) authors on the previous reviews reporting parent-mediated early interventions and/or play-based interventions in autistic samples (Althoff et al., 2019; Beaudoin et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2023; Conrad et al., 2021; Dijkstra-de Neijs et al., 2021; Dyches et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2021; Harrop, 2015; Heidlage et al., 2020; Kent et al., 2020; Law et al., 2021; Lee & Meadan, 2021; Liu et al., 2020; López-Nieto et al., 2022; Naveed et al., 2019; Nevill et al., 2018; O’Keeffe & McNally, 2021; Oono et al., 2013; Shalev et al., 2020; Tachibana et al., 2017; Trembath et al., 2019; Verschuur et al., 2014; Waddington et al., 2021). The identified studies were then merged and carried into abstract and full-text screenings which were conducted by two authors (ED and GF) to make sure no eligible study was overlooked. Any discrepancies between the two coders, at the title and abstract screening, were resolved by the third author (CT).

Data Extraction

Descriptive Information

Information related to intervention types, play approaches, sample sizes, experimental designs, etc., was extracted to report the included study characteristics.

Quantified Data

Quantified outcomes including sample size, means, and standard deviations were extracted. For the meta-analyses, as stated in the study protocol (Deniz et al., 2022), we extracted one outcome for each domain—social communication, language, and autistic characteristics—using the following pre-specified algorithm: the pre-specified primary outcome(s) (where provided); the first outcome reported in text or table in the included studies. Prior to data extraction, we checked whether all reported measures were coded in the same direction. According to the characteristics of the measures, we determined increased mean scores to be indicators of improved outcomes (i.e., social communication, language, and autistic characteristics). In cases where a measure was coded in an opposite direction, (i.e., higher scores mean worse outcomes), we then reverse-coded intervention and control groups to account for this. All data were double extracted using a specially devised data extraction form (Deniz et al., 2022). The first author (ED) extracted data from all included studies, and each of the other authors (GF, CT, and UT) extracted data from a third of the first author’s sample. Any discrepancies between the coders regarding the extracted data were discussed and resolved. In cases where two coders were not able to come to an agreement, discrepancies were resolved by consultation with the third and fourth coders.

Quality Appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by all four authors with the first author assessing all (ED) and each of the others (CT, GF, and UT) assessing a third of the sample, independently. The authors used two risk of bias (RoB) tools one of which is for randomised controlled trials and the other for quasi-experimental designs (Deniz et al., 2022). Both risk of bias forms were previously adapted (Francis et al., 2022) from the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2; Sterne et al., 2019) and Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions’ (ROBINS-1; Sterne et al., 2016). Each tool has five domains that assess the following items: random allocation and concealment of allocation, blinding to the intervention, appropriate measurement, reported and selected outcomes, a prior analysis plan and a protocol. Methodological quality of the included studies was summarised as (i) low risk of bias, (ii) some concerns of bias, and (iii) high risk of bias. The overall RoB was judged as low risk of bias if the study was judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains, some concerns if the authors had some concerns in any domains, and high if any domains were judged as high risk of bias (Sterne et al., 2016, 2019). While risk of bias results were not used to exclude any studies from the current review, studies with a high risk of bias were excluded from the meta-analyses.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical software R version 4.2.1 (R Core team, 2022). Given that the data on study outcomes, in this context, was highly heterogeneous, random effects meta-analyses were performed. To do this, the reported outcome variables were categorised under three umbrella terms: (i) social communication skills, (ii) language skills, and (iii) autistic characteristics. The overall effectiveness of the interventions on the social communication, language, and autistic characteristics outcomes were reported by using standardised mean differences (Cohen’s d). Additionally, since the sample size of the current study was relatively small, the statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics. Subgroup analyses were also carried out to check whether the pooled effect sizes were predicted (moderated) by any aspects of study/intervention characteristics. As the number of subgroups increases, the probability of getting false-positive results due to underpowered samples increases (Burke et al., 2015). To prevent this, subgroup analyses were performed with the limitation that each subgroup had three or fewer groups.

Missing Data

All included studies were checked in terms of missing data. Studies with no sufficient quantified data were removed from the reported meta-analyses.

Diversions from Study Protocol

In the protocol (Deniz et al., 2022), we suggested that we would extract the total score of a measure instead of their subdomain scores where possible. However, this was not applied to all measures due to some subscales being a better indicator of the scales’ total scores for the target outcome. For instance, the VABS-total score provides a sum score of adaptive functioning including not only social communication but also daily living and motor skills. Similarly, the MSEL total score is an indicator of not only language skills but also visual perception and fine motor skills. In such cases, instead of the total score, we extracted either the communication or socialisation subdomain of the VABS and the expressive or receptive language subdomain of the MSEL, depending on which was the first reported outcome.

Position Statement

All authors are neurotypical researchers (i.e., not autistic) with a commitment to supporting the development of autistic children so that they have good opportunities to engage meaningfully and fulfillingly with both neurotypical and neurodivergent populations, as they see fit. In this work, autistic characteristics were included as one of the outcomes because they were the primary outcome in some of the included studies and some measures labelled as “autistic characteristics” in previous studies also capture aspects of social communication. We view autism as a difference in the human population without any sort of hierarchy (i.e., being autistic is not better or worse than being neurotypical, it is different). We reject the idea that autism needs to be cured or changed, and we do not intend for our work to be interpreted for this purpose.

Results

Study Selection Results

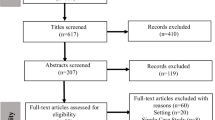

The database screening and citation searching of previously published reviews, see (Fig. 1), yielded a total of 604 studies 305 of which were duplicates. Of these, 299 (after duplicates were dropped) were included in the abstract screening 99 of which were further excluded due to not meeting one or more inclusion criteria. Hence, 200 studies were carried into full-text screening. Of the 200 full-text screened, 174 were further excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria for the following reasons: (a) upper age limit greater than 72 months; (b) no official autism diagnosis or screening; (c) study protocol or commentary, study design; (d) comparison of two or more play-based interventions; (e) no parental involvement; (f) interventions conducted in educational settings; (g) same dataset used in multiple publications; (h) full-text not available; and (i) interventions published in languages other than English. Hence, 26 studies were included in this review, 21 of which were carried into the meta-analyses. Of five excluded studies, fourFootnote 2 did not report sufficient quantified outcomes and oneFootnote 3 showed a high risk of bias. Data is synthesised for outcomes related to social communication, language, and autistic characteristics following the outcome selection procedure outlined in the study protocol. A detailed list of extracted outcomes is shown in Table S1 (supplementary materials).

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies and interventions are summarised here in brief. A detailed summary of study characteristics can also be accessed in supplementary materials (Table S2).

Study Contexts. The included papers comprised 24 peer-reviewed journal articles and two unpublished PhD dissertations. The majority of the studies were conducted in the USA (N = 18), and the remaining studies were undertaken in China (N = 2), England (N = 1), Taiwan (N = 1), Thailand (N = 1), Australia (N = 1), Canada (N = 1), and Netherlands (N = 1).

Study Designs. The included studies comprised 23 RCTs with participants being randomly allocated to intervention and control groups and three QEDs where participants were non-randomly assigned to intervention and control groups. The conditions experienced by control group participants included either being assigned to a waitlist control condition with care as usual (N = 10); treatment as usual (N = 9), which included participants receiving routine care like community services; and active controls (N = 7) utilising non-play-based interventions like a psycho-educational intervention, caregiver education module, picture exchange communication system, and community-based verbal behaviour.

Sample Characteristics. Included studies had a total sample of N = 1459 autistic children aged 12 to 72 months. Consistent with other studies conducted with autistic children, almost all studies had a significantly higher proportion of male (N = 1107) than female (N = 263) participants. This means, about 80% of the included studies’ sample, on average, were male (Note: Three studies did not report their participants’ gender).

Interventions. There were various types of parent-mediated play-based interventions delivered in the included studies some of which were validated while others were not. Researchers delivered the following pre-validated—i.e., manualised-parent-mediated play-based interventions: Pivotal Response Treatment (N = 6); Early Start Denver Model (N = 4); Joint Attention Symbolic Play Engagement and Regulation (N = 3); Developmental, Individual-Difference, Relationship-based Floortime (N = 1); Responsive Education and Prelinguistic Milieu Teaching (N = 1); Hanen More than Words (N = 2); the Family Implemented TEACCHFootnote 4 for Toddlers (N = 1); the Building Block Home Based Program (N = 1); the PLAY Project (N = 1); Parent–Child SandPlay (N = 1); Joint-Attention Mediated Learning (N = 1); Caregiver-Mediated Joint Engagement (N = 1); and Focus Parent Training (N = 1). There were also interventions that were not previously validated; Home-Based Intervention (N = 1) and Social Communication Intervention (N = 1). All validated interventions utilised manualised programs.

Interventionists. Who delivered the intervention varied amongst the included studies. Most commonly, interventions were delivered by therapists or clinicians (N = 16), though there were cases where the intervention was delivered by less professional interventionists such as trained interventionists (N = 7)—e.g., psychology/education students or graduates and psychologists, or a transdisciplinary team comprising teachers, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, and psychologists (N = 3). In general, the main role of the interventionists was to train or coach parents in how to engage in playful interactions with their child to improve their social communication and language skills.

Intervention Setting. The interventions centred around engaging children in diverse forms of play like child-initiated play (N = 6), naturalistic play (N = 6), free play (N = 5) symbolic/pretend play (N = 6), and structured play (N = 3). The interventions were mostly conducted in participants’ homes (N = 18). Additionally, four studies conducted hybrid interventions (i.e., at home and elsewhere—i.e., clinic, daycare centre), and one study held interventions in a specially arranged treatment room. Finally, details about the setting of the intervention were not specified in some studies (N = 3).

Intervention Length. A great variation was observed in the length and the frequency of delivered parent-mediated play-based interventions. The overall length of the interventions varied from approximately 6 weeks to 104 weeks. The frequency of interventions varied from 30 min a week to 20 h a week. In total, ten included studies delivered interventions longer than 6 months, and 11 trials delivered interventions shorter than 6 months. This is a great amount of variation in the intervention length and frequency which is likely to impact upon the effectiveness of the interventions on the targeted outcomes of autistic children. Therefore, we further analysed whether the total duration of the interventions (greater or shorter than 6 months) played a role in the efficacy of the interventions.

Mediator Training. All studies explicitly reported that parents acted as the mediators of the intervention they delivered. Of these, most interventions trained parents to boost the efficacy of the interventions. The mediator training involved activities like parent coaching and supervision (N = 12), modelling and video feedback (N = 1), educational training and psycho-educational workshops (N = 7), and parent group sessions (N = 3). In one study,Footnote 5 parents received no training and two studiesFootnote 6 did not report the type mediator’s training.

Social Communication Skills. The social communication outcome measures included The Griffiths Development Scales-Chinese (N = 2); Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (N = 9); the Child Behaviour Rating Scale (N = 1); the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change (N = 1); Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile (N = 1), Early Social Communication Scales (N = 1), and Social Responsiveness Scale (N = 1). Additionally, seven researchers developed or adopted systematic coding of observed social communication skills. Three studies did not report any social communication outcomes.

Language Skills. The impact of the interventions on language skills are inferred from the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (N = 3), the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (N = 8), The Griffiths Development Scales-Chinese (N = 1), the Reynell Developmental Language Scales (N = 2), and the Griffiths Developmental Scales-Chinese Version (N = 1). Additionally, four studies used observational measures in reporting language outcomes; “frequency of child’s number of total words (N = 1), structured laboratory observation (N = 2), and video coding (N = 1).” Seven studies did not report any language outcomes. There were also observational/non-valid scales.

Autistic Characteristics. The most frequently used measure of autistic characteristics was the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (N = 7). Alternatively, some studies used the Social Responsiveness Scale (N = 1), the Social Communication Questionnaire (N = 1), the Autism Behaviour Checklist (N = 1), and The Parent Interview for Autism-Clinical Version (N = 2). The remaining included studies (N = 14) did not report autistic characteristics as a primary or secondary outcome.

Quality Appraisal Results

All included studies were individually and independently appraised by authors. Separate assessments were conducted for RCTs (N = 23) and QEDs (N = 3) which ensured that the risk of bias assessment tool appropriately matched the study research design. The risk of bias results are reported for the five domains assessed along with the overall risk of bias judgement (see Tables 1 and 2).

For RCTs, all studies met the random allocation criterion. While the majority of RCTs (N = 20) met the allocation sequence concealed criterion, the allocation sequence was not concealed in five studies. Also, one study provided no information regarding the concealment of the allocation sequence. Additionally, in the majority of included RCTs, participants (N = 13) and parents/carers and interventionists (N = 11) were not aware of their assigned groups. Moreover, in the majority of the included RCTs (N = 16), outcome data were available for all/nearly all participants. Only in two RCTs, there were high rates of attrition with no evidence that results were not biased due to missing data. In terms of the use of appropriate measures, it appeared that only one study may not have used an appropriate method to measure the outcome variable, namely, an object interest measure, due to the unstandardised characteristic of the measure. Furthermore, the majority of included RCTs (N = 18) appeared to have some sort of pre-specified analysis plan (i.e., registered trial, study protocol, funding statement). There was only one study that posed the risk of reporting selected outcomes as the study did not have any kind of trial registration or a priori protocol. Overall, the majority of the RCTs were judged as having some risk of bias concerns (N = 13), eight studies were judged as low risk of bias, and two studies received a high risk of bias judgement.

For the three QEDs, there was no evidence of bias due to confounding effects or participant selection. The intervention groups of the QEDs were clearly defined, and information to define the intervention group was recorded prior to the intervention. In all three QEDs, there was low risk of attrition bias as either the outcome data were available for all or nearly all participants or there was evidence that the results were not biased due to missing data. All three QEDs used appropriate methods to measure the reported outcome variables. Although only one QED included a pre-specified analysis plan and a priori protocol, there appeared to be no risk for reported selected outcomes in either QEDs. Overall, one study was judged as having low risk of bias while the remaining two QEDs were judged as having some risk of bias concerns.

Meta-analytic Results

In total, 21 studies were included in the meta-analyses reporting the effectiveness of parent-mediated play-based interventions on social communication skills (N = 20), language skills (N = 15), and autistic characteristics (N = 12) in preschool autistic children. Random effects meta-analyses were performed to report the overall effect sizes due to the high heterogeneity found in the characteristics of the included studies. Subgroup analyses were also performed to test the moderator role of the study and intervention characteristics.

Social Communication Skills

The combined sample of 20 studies comprised 1131 preschool autistic children. Of the 20 studies, 14 trials individually reported positive effect sizes, of which eight were statistically significant, ranging from 0.66 (0.06, 1.26) to 3.34 (2.73, 3.95). Pooling individual effect sizes from 20 studies indicated a significant positive medium effect size (d = 0.63, CI = 0.21, 1.05, z = 2.94, p < 0.001; I2 = 90%, τ2 = 0.82) suggesting that autistic children who received parent-mediated play-based interventions had significantly better social communication skills than those in the control groups. Detailed results can be found in forest plot-1 (see Fig. 2).

Language Skills

In total, 15 studies reported the means and standard deviations for the language outcomes which in total comprised a sample of 845 preschool autistic children. Of these, 12 trials individually indicated positive effect sizes; five of which were statistically significant. The statistically significant effect sizes ranged from 0.61 (0.01, 1.21) to 2.55 (1.54, 3.57). A random effects meta-analysis was conducted to pool the individual effect sizes which indicated a statistically significant positive medium effect size (d = 0.40, CI = 0.09, 0.71, z = 2.52, p < 0.01; I2 = 72%, τ2 = 0.52). That said, autistic children who received parent-mediated play-based interventions significantly improved their language skills compared to the ones who did not receive such interventions. Detailed findings are shown in forest plot-2 (see Fig. 3).

Autistic Characteristics

Of the 21 studies included in this meta-analysis, 12 studies (N = 679) reported whether interventions showed any effects on the autistic characteristics of preschool autistic children. All of these, but one study, reported certain changes in the autistic characteristics of their sample (i.e., individuals scored lower on autism screening measures post-intervention compared to baseline). A pooled meta-analysis of 12 studies indicated a significant small effect size (d = − 0.19, CI = − 0.34, − 0.03, z = − 2.24, p = 0.02; I2 = 29%, τ2 = 0.002). This suggests that parent-mediated play-based interventions had a small but significant effect on the autistic characteristics of preschool autistic children (i.e., individuals scored lower on autism screening measures). More information is shown in forest plot-3 (see Fig. 4).

Heterogeneity

There was high statistical heterogeneity and between study variances in the meta-analyses of social communication (Q = 194.29, df = 19, p < 0.01, I2 = 90%, τ2 = 0.82) and language outcomes (Q = 49.29, df = 14, p < 0.01, I2 = 72%, τ2 = 0.52) potentially suggesting that the included studies may not share a common effect size. For autistic characteristics, however, there was neither statistically significant heterogeneity nor between study variance (Q = 15.58, df = 11, p = 0.16, I2 = 29%, τ2 = 0.002), indicating that included trials had similar characteristics.

Publication Bias and Influence on Findings

To assess whether the included studies posed any publication bias on the meta-analysis, we performed Egger’s test on each outcome. For the social communication outcome, Egger’s test results indicated (t = 1.55, df = 18, p = 0.14) no potential for publication bias. However, the linear regression of funnel plot asymmetry indicated potential publication bias in the meta-analyses of language skills (t = 3.42, df = 13, p < 0.01) and autistic characteristics (t = − 4.40, df = 10, p < 0.01). Funnel plots for publication bias can be seen in Figures S1-S3 (supplementary materials).

In terms of the influence of individual studies on reported pooled effect sizes, all included studies showed an average influence on the pooled effect sizes suggesting that the pooled effect sizes are not driven by any individual outlier study. Forest plots for influence analysis can be seen in Figures S4-6 (supplementary materials).

Subgroup Analyses

We also conducted subgroup analyses to test whether certain study characteristics such as study design, methodological quality, intervention provider, and intervention length moderate the efficacy of interventions on the pooled effect sizes for social communication, language, and autistic characteristics outcomes. Findings are summarised below, and detailed information is shown in Figures S7-18 (supplementary materials).

Study Design. In terms of study design, trials that randomly assigned participants to intervention and control groups were significantly effective on social communication skills (N = 18, d = 0.58, CI = 0.14, 1.01) and autistic characteristics (N = 11, d = -0.19, CI = -0.36, -0.02) of preschool autistic children while those with non-random allocation reported non-significant effect sizes, respectively (N = 2, d = 1.12, CI = -0.97, 3.21; N = 1, d = -0.23, CI = -0.86, 0.40). However, for both outcomes, the between-group differences were insignificant, respectively (Q = 0.25, df = 1, p = 0.61; Q = 0.02, df = 1, p = 0.89) suggesting that the significant pooled effect sizes found for both outcomes were not predicted by the designs of the included studies. Similarly, although both RCT (N = 14, d = 0.19, CI = 0.05, 0.33) and QED (N = 1, d = 1.38, CI = 0.71, 2.05) trials were effective in improving language skills, a significant between-group difference was found which favoured the QED trial over RCTs. This, however, could be attributed to the fact that there was only one QED trial compared to 14 RCTs. Detailed findings can be seen in forest plots S7-S9 (supplementary materials).

Methodological quality. It is important to evaluate the methodological quality of the reported effect sizes, especially when they are significant and promising. In the current study, we found that parent-mediated play-based interventions have significant effects on improving social communication and language skills and autistic characteristics of preschool autistic children. Subgroup analyses revealed that pooling effect sizes across trials with high methodological quality (i.e., low risk of bias) did not indicate any significant effects on either social communication (N = 9, d = 0.38, CI = -0.21, 0.96) or language skills (N = 7, d = 0.54, CI = -0.15, 1.24) while those with some methodological concerns pooled significant intervention effects for both outcomes, respectively (N = 11, d = 0.85, CI = 0.25, 1.43; N = 8, d = 0.24, CI = 0.05, 0.43). However, these between-group differences were not statistically significant for either social communication (Q = 1.22, df = 1, p = 0.26) or language (Q = 0.65, df = 1, p = 0.42) outcomes. Despite this, studies with high methodological quality pooled a significant effect size for autistic characteristics outcomes while those with some methodological concerns were not effective and this difference was statistically significant (Q = 4.23, df = 1, p = 0.04).

Intervention Provider. There was a degree of range in terms of who delivered the intervention amongst the included studies, therefore, it appeared important to test whether this had any impact on the efficacy of interventions. In terms of social communication outcomes, interventions that were delivered by therapist/clinicians or trained interventions were significant while those delivered by an interdisciplinary team were not. In regard to language skills and autistic characteristics, however, only the interventions that were delivered by therapists/clinicians were significantly effective. It is, however, important to acknowledge that the between-group differences in the effectiveness of interventions were not significant for either social communication (Q = 0.51, df = 2, p < 0.77), language (Q = 4.26, df = 2, p < 0.12), or autistic characteristics (Q = 2.03, df = 2, p < 0.36) outcomes. That is, although therapist/clinician-delivered interventions may look more promising, statistically, the efficacy of such interventions does not seem to depend on the provider.

Intervention Length. As stated earlier, the included studies varied in terms of the duration and frequency of the interventions they delivered. It appeared that, of the 21 studies included in the current meta-analysis, the general pattern showed interventions either lasted longer than six months (N = 10) or shorter than six months (N = 11). Taken from here, we look to see whether interventions lasting longer than six months (26 weeks) were more effective than the shorter-term interventions. On this, interventions lasting longer than six months provided a significant positive effect for both social communication (N = 10, d = 0.99, CI = 0.31, 1.68) and language skills (N = 9, d = 0.60, CI = 0.08, 1.12) while those shorter than six months were non-significant (Social communication = N = 10, d = 0.28, CI = -0.15, 0.71; Language = N = 6, d = 0.14, CI = -0.13, 0.40). Although long-term interventions seemed more promising than short-term ones, it is important to note that there were no statistically significant between-group differences in the effectiveness of interventions on social communication (Q = 2.98, df = 1, p < 0.98), language (Q = 2.43, df = 1, p < 0.12), or autistic characteristics (Q = 1.35, df = 1, p < 0.24).

Discussion

The current study systematically reviewed and evaluated the evidence on the effectiveness of parent-mediated play-based interventions on social communication skills, language skills, and autistic characteristics of autistic preschoolers. We found that parent-mediated play-based interventions had significant effects on social communication (d = 0.63) and language skills (d = 0.40) as well as autistic characteristics (d = -0.19) of autistic preschoolers. Although interventions lasting longer than six months and those delivered by clinicians/therapists seemed more promising, statistically, study and intervention characteristics (i.e., design, methodological quality, interventionist, intervention length) did not seem to play a significant role on the efficacy of the included trials.

A pooled effect size of the studies included in the meta-analysis indicated moderate improvement in the social communication skills of preschool autistic children. This aligns well with recent reports from the literature which indicate significant improvement in the social communication skills of autistic children following other types of parent-mediated early interventions (Cheng et al., 2023; Dyches et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Nevill et al., 2018; Kent et al., 2020; O’Keeffe & McNally, 2021; Tachibana et al., 2017). Additionally, our findings also indicated that interventions targeting the language skills of preschool autistic children have a positive effect, which is also well supported by previous similar meta-analyses in the literature (Cheng et al., 2023; Heidlage et al., 2020; Nevill et al., 2018; Oono et al., 2013). These findings provide further promise that play-based interventions that are delivered by parents outside of an educational setting are likely to be beneficial for autistic children’s social communication and language skills in the preschool years.

We chose to include an evaluation of intervention effects on autistic characteristics, as it is difficult to disentangle some of these from social communication and language skills, the primary focus of this study. Nearly all studies included in the meta-analysis indicated somewhat improved behaviours related to the autistic characteristics of autistic preschoolers. A pooled effect size further indicated that play-based interventions are effective in modifying the autistic characteristics of autistic preschoolers. Our findings are also supported by previous reviews which reported that parent-mediated early interventions (Dyches et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Nevill et al., 2018; Oono et al., 2013) and play-based interventions (Dijkstra-de Neijs et al., 2021) are effective in improving autistic characteristics of young autistic children. It is also important to note that, in the current meta-analysis, the interventions suggesting improved autistic characteristics had high methodological quality. This is promising as it minimises the chances for false-positive results (Higgins et al., 2019) and suggests that such interventions may actually be effective in improving the quality of life for autistic preschoolers.

We are confident that our findings were not subject to confounding effects. The subgroup analyses indicated no significant moderator effects for the methodological quality,Footnote 7 intervention provider, and intervention duration for either reported outcome. This added to the confidence of our reported results, as it demonstrates that the significant effect sizes reported for social communication skills, language skills, and autistic characteristics were not dependent on such study or intervention characteristics. However, although there were no statistically significant between-group differences, similar to what Cheng et al., (2023) reported, studies with high methodological quality indicated non-significant effect sizes for social communication and language skills, while studies with some methodological concerns indicated significant effect sizes. The replication of this previously reported finding in our meta-analysis raised concerns over whether the significant effect sizes for such interventions are predicted by methodological biases. Adding to this, we found a significant subgroup difference between the RCT and QED studies, favouring the QED sample, for language skills which further increased our concerns over the prior mentioned issue. Therefore, it strikes important to draw scientific attention to the methodological quality of interventions aiming to improve the social communication and language skills of autistic children. Lastly, findings for social communication and language outcomes should be evaluated cautiously as there was high statistical heterogeneity and between-study variance not only in the current study but also in similar previous meta-analyses (Cheng et al., 2023; Nevill et al., 2018; Oono et al., 2013; Tachibana et al., 2017). Based on our findings as well as the past reports, we believe that high heterogeneity may be a common issue in meta-analyses of studies reporting the social communication and language skills of autistic children.

Caveats and Further Considerations

It is important to consider that the current review indicated a publication bias for studies reporting the efficacy of parent-mediated play-based interventions on the language skills and autistic characteristics of autistic preschoolers. There may be several reasons why publication bias occurred in this review. For example, it may be that trials reporting significant treatment effects on language skills and autistic characteristics may be more likely to get published compared to those reporting non-significant outcomes (Thornton & Lee, 2000). Additionally, although the current study included the grey literature, i.e., unpublished studies—published trials have a higher likelihood of identification and inclusion compared to non-published ones due to their greater visibility. Furthermore, the detected publication bias may as well be due to the poor methodological quality of studies delivering such interventions in this field, for example, most trials conducted with autistic children have very small sample sizes (i.e., n < 50 in intervention and control groups) which limits the ability for random allocation (Higgins et al., 2019; Rothstein et al., 2005). Hence, the publication bias found for language skills and autistic characteristics is concerning as it suggests that the reliability of the significant effect sizes for both outcomes may have been affected by publication bias, and, therefore, need to be cautiously interpreted.

A major strength of the current review is that the study design, statistical analyses, and reported outcomes are in accordance with a pre-registered study protocol. This eliminates the selective reported outcome bias in the review. Additionally, the methodology of the current review (design, conduct and reporting of the outcomes) was guided by the PRISMA statement and adapted versions of the widely used Cochrane quality assurance tools in evaluating the risk of bias in the included studies. Furthermore, excluding studies with a methodologically high risk of bias from the meta-analyses potentially increased the reliability of reported findings and decreased the probability of false positive results.

The study findings should be interpreted with a number of caveats in mind. The focus of the current work was on child-level outcomes. This does not tell us anything about why interventions work. That is, parental training and involvement are likely to also improve parents’, as well as children’s social communication and language skills. Therefore, future research should also focus on parent-level outcomes to understand the mechanisms through which interventions might exert their influence. Additionally, we only reported one outcome per target domain per study (i.e., social communication skills, language skills, and autistic characteristics). This is common practice in the field (e.g., Borairi et al., 2021) but does not rule out the possibility that applying a different data extraction strategy could provide different results in the current study. We were also concerned by the sample sizes used in many of the studies included in the current analysis. We recognise the difficulties with recruiting autistic populations. It remains the case that randomisation only works in a large enough sample and that randomisation using small sample sizes may not create unbiased groups. However, we chose not to classify studies as high risk of bias based solely on sample size, as this would mean almost all studies would be high risk of bias. It is important to note that studies published by non-native English speakers or those from non-English speaking countries may have slightly different wording for the search strings used in the current study which may have been missed in the review. Therefore, future researchers may wish to take a different screening approach to capture such studies. Finally, some other child-level variables such as age and gender that could not be tested in the current review have the potential to moderate the intervention effects. It seems perfectly plausible that interventions might work differently for different stages of development. All findings should be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

Moreover, we have provided a synthesis on the intersection of interventions with pre-school aged autistic children using parent training and play-based interventions under the umbrella of parent-mediated play-based interventions. Our findings illuminate the efficacy of parent-mediated play-based interventions to both practitioners/therapists and parents who grapple with making decisions about which interventions are better suited for supporting the young autistic children in their care. There are an increasing number of interventions for autistic children that use parents as interventionists; hence, our attempt at using a homogeneous grouping of these interventions (e.g., play-based and with preschoolers) will likely make it easier for practitioners to navigate the evidence from these techniques.

Conclusions

Parent-mediated play-based interventions have gained popularity in recent years; 25 of the 26 studies included in this review were conducted after 2010. In summary, our meta-analysis demonstrates that parent-mediated play-based interventions have positive effects on autistic children’s social communication and language skills as well as on their autistic characteristics during the preschool years. These findings provide further impetus to empower parents in supporting their autistic children’s development. Interventions delivered by trained professionals in educational settings can be resource intensive and not well received by autistic children as educational environments can be particularly stressful for autistic children. Parent-mediated interventions can be provided outside educational environments, in low resource settings, and in environments where autistic children are more likely to engage and benefit.

Data Availability

The raw data for this meta-analysis can be found on the relevant OSF project page (https://osf.io/yz3se/).

Notes

This is to capture the following search terms: autism an d autistic.

Lieberman, 2011, Oosterling et al., 2010, Pajareya & Nopmaneejumruslers, 2011, Stock et al., 2013.

Greenfield, 2020.

FITT is based on the University of North Carolina TEACCH Autism Program - Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH).

Liu et al., 2023

Mcduffie et al., 2012, Stock et al., 2012.

Except for the outcome “autistic characteristics,”—i.e., studies with higher methodological quality provided significant improvement-

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- QED:

-

Quasi-experimental design

- SCE:

-

Single-case experimental

- ESDM:

-

Early Start Denver Model

- PRT:

-

Pivotal response treatment

- JASPER:

-

Joint Attention, Symbolic Play, and Engagement Regulation

- DIR/Floortime:

-

Developmental, Individual-Difference, Relationship-Based Model

- RPMT:

-

Responsive Education and Prelinguistic Milieu Teaching

- HMTW:

-

Hanen More Than Words

- FITT:

-

Family Implemented TEACCH for Toddlers

- HB:

-

Building Block Home-Based Program

References

References with asterisks are those included in the performed meta-analyses

*Aldred, C., Green, J., & Adams, C. (2004). A new social communication intervention for children with autism: Pilot randomised controlled treatment study suggesting effectiveness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(8), 1420-1430https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00338.x.

Althoff, C. E., Dammann, C. P., Hope, S. J., & Ausderau, K. K. (2019). Parent-mediated interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(3), 7303205010p1-7303205010p13. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.030015

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

*Barrett, A. C., Vernon, T. W., McGarry, E. S., Holden, A. N., Bradshaw, J., Ko, J. A., ... & German, T. C. (2020). Social responsiveness and language use associated with an enhanced PRT approach for young children with ASD: Results from a pilot RCT of the PRISM model. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 71, 101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101497.

Beaudoin, A. J., Sébire, G., & Couture, M. (2014). Parent training interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism research and treatment, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/839890.

Bergen, D. (2002). The role of Pretend Play in Children’s Cognitive Development. Childhood Education; Olney, 85(3), 210.

Borairi, S., Fearon, P., Madigan, S., Plamondon, A., & Jenkins, J. (2021). A mediation meta-analysis of the role of maternal responsivity in the association between socioeconomic risk and children’s language. Child Development, 92(6), 2177–2193. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13695

Burke, J. F., Sussman, J. B., Kent, D. M., & Hayward, R. A. (2015). Three simple rules to ensure reasonably credible subgroup analyses. Bmj, 351. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5651.

*Carter, A. S., Messinger, D. S., Stone, W. L., Celimli, S., Nahmias, A. S., & Yoder, P. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of Hanen’s ‘More Than Words’ in toddlers with early autism symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(7), 741–752.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02395.x.

Cheng, W. M., Smith, T. B., Butler, M., Taylor, T. M., & Clayton, D. (2023). Effects of parent-implemented interventions on outcomes of children with autism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05688-8.

*Chiang, C. H., Chu, C. L., & Lee, T. C. (2016). Efficacy of caregiver-mediated joint engagement intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 20(2), 172-182https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315575725.

Conrad, C. E., Rimestad, M. L., Rohde, J. F., Petersen, B. H., Korfitsen, C. B., Tarp, S., ... & Händel, M. N. (2021). Parent-mediated interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 2067. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.773604.

Craig-Unkefer, L. A., & Kaiser, A. P. (2002). Improving the social communication skills of at-risk preschool children in a play context. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112140202200101

Danger, S., & Landreth, G. (2005). Child-centered group play therapy with children with speech difficulties. International Journal of Play Therapy, 14, 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088897

*Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., ... & Varley, J. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125(1), e17-e23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0958.

Deniz, E., Francis, G., Torgerson, C., & Toseeb, U. (2022). Parent-mediated play-based interventions to improve social communication and language skills of preschool autistic children: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0270153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270153

Dijkstra-de Neijs, L., Tisseur, C., Kluwen, L. A., van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A., Swaab, H., & Ester, W. A. (2021). Effectivity of play-based interventions in children with autism spectrum disorder and their parents: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05357-2.

Dyches, T. T., Smith, T. B., Korth, B. B., & Mandleco, B. (2018). Effects of parent-implemented interventions on outcomes of children with developmental disabilities: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Early Childhood Psychology and Education, 3(1), 137–168.

Feuerstein, R., Klein, P. S., & Tannenbaum, A. J. (1991). Mediated Learning learning Experience experience (MLE): Theoretical. Freund Publishing House Ltd.

Francis, G., Deniz, E., Torgerson, C., & Toseeb, U. (2022). Play-based interventions for mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis focused on children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and developmental language disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969415211073118.

*Gengoux, G. W., Abrams, D. A., Schuck, R., Millan, M. E., Libove, R., Ardel, C. M., ... & Hardan, A. Y. (2019). A pivotal response treatment package for children with autism spectrum disorder: An RCT. Pediatrics, 144(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0178.

Gibson, J. L., Pritchard, E., & de Lemos, C. (2021). Play-based interventions to support social and communication development in autistic children aged 2–8 years: A scoping review. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 6, 23969415211015840. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F23969415211015840

Goods, K. S., Ishijima, E., Chang, Y.-C., & Kasari, C. (2013). Preschool based JASPER intervention in minimally verbal children with autism: Pilot RCT. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(5), 1050–1056.

*Greenfield, E. (2020). Pilot RCT of an online pivotal response treatment training program for parents of toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. [Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of California]. Santa Barbara.

Han, M., Moore, N., Vukelich, C., & Buell, M. (2010). Does play make a difference? How play intervention affects the vocabulary learning of at-risk preschoolers. American Journal of Play, 3(1), 82–105.

*Hardan, A. Y., Gengoux, G. W., Berquist, K. L., Libove, R. A., Ardel, C. M., Phillips, J., ... & Minjarez, M. B. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of Pivotal Response Treatment Group for parents of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(8), 884–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12354.

Harrop, C. (2015). Evidence-based, parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder: The case of restricted and repetitive behaviors. Autism, 19(6), 662–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314545685

Heidlage, J. K., Cunningham, J. E., Kaiser, A. P., Trivette, C. M., Barton, E. E., Frey, J. R., & Roberts, M. Y. (2020). The effects of parent-implemented language interventions on child linguistic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 50, 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.006

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 978–0–470–69951–5 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604.

Hu, X., Zheng, Q., & Lee, G. T. (2018). Using peer-mediated LEGO® play intervention to improve social interactions for chinese children with autism in an inclusive setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(7), 2444–2457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3502-4

Jeong, J., Franchett, E. E., de Oliveira, C. V. R., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021). Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 18(5), e1003602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602

*Kasari, C., Gulsrud, A. C., Wong, C., Kwon, S., & Locke, J. (2010). Randomized controlled caregiver mediated joint engagement intervention for toddlers with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 40(9), 1045-1056https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0955-5.

*Kasari, C., Lawton, K., Shih, W., Barker, T. V., Landa, R., Lord, C., ... & Senturk, D. (2014). Caregiver-mediated intervention for low-resourced preschoolers with autism: An RCT. Pediatrics, 134(1), e72-e79. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3229.

*Kasari, C., Gulsrud, A., Paparella, T., Hellemann, G., & Berry, K. (2015). Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 554–563https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039080.

Kent, C., Cordier, R., Joosten, A., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Bundy, A., & Speyer, R. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to improve play skills in children with Autism autism Spectrum spectrum Disorderdisorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00181-y

Kjelgaard, M. M., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2001). An Investigation investigation of Language language Impairment impairment in Autismautism: Implications for Genetic genetic Subgroupssubgroups. Language and Cognitive Processes, 16(2–3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960042000058

Kuhaneck, H., Spitzer, S. L., & Bodison, S. C. (2020). A systematic review of interventions to improve the occupation of play in children with autism. OTJR: Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 40(2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449219880531

Landa, R., & Garrett-Mayer, E. (2006). Development in infants with autism spectrum disorders: A prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(6), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01531.x

Law, M. L., Singh, J., Mastroianni, M., & Santosh, P. (2021). Parent-mediated interventions for infants under 24 months at risk for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05148-9.

Lee, J. D., & Meadan, H. (2021). Parent-mediated interventions for children with ASD in low-resource settings: A scoping review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00218-7

*Lieberman, R. G. (2011). Effects of a parent-mediated intervention on object play and play’s association with communication in young children with autism spectrum disorder [Doctoral thesis, Vanderbilt University]. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. (1467749192). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-parent-mediated-intervention-on-object/docview/1467749192/se-2.

Lillard, A. S., & Kavanaugh, R. D. (2014). The contribution of symbolic skills to the development of an explicit theory of mind. Child Development, 85(4), 1535–1551. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12227

Liu, Q., Hsieh, W. Y., & Chen, G. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent-mediated intervention for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Autism, 24(8), 1960–1979. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320943380

*Liu, G., Chen, Y., Ou, P., Huang, L., Qian, Q., Wang, Y., ... & Hu, R. (2023). Effects of Parent-Child Sandplay Therapy for preschool children with autism spectrum disorder and their mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 71, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2023.02.006.

López-Nieto, L., Compañ-Gabucio, L. M., Torres-Collado, L., & Garcia-de la Hera, M. (2022). Scoping Review review on Playplay-Based based Interventions interventions in Autism autism Spectrum spectrum Disorderdisorder. Children (basel, Switzerland), 9(9), 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091355

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., et al. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ, 70(No. SS-11), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1

*Mcduffie, A. S., Lieberman, R. G., & Yoder, P. J. (2012). Object interest in autism spectrum disorder: A treatment comparison. Autism, 16(4), 398-405https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361309360983.

Mercer, J. (2017). Examining DIR/FloortimeTM as a Treatment treatment for Children children With with Autism autism Spectrum spectrum Disordersdisorders: A Review review of Research research and Theorytheory. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(5), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515583062

Naveed, S., Waqas, A., Amray, A. N., Memon, R. I., Javed, N., Tahir, M. A., Ghozy, S., Jahan, N., Khan, A. S., & Rahman, A. (2019). Implementation and effectiveness of non-specialist mediated interventions for children with Autism autism Spectrum spectrum Disorderdisorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0224362. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224362

Nevill, R. E., Lecavalier, L., & Stratis, E. A. (2018). Meta-analysis of parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(2), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316677838

O’Keeffe, C., & McNally, S. (2021). A systematic review of play-based interventions targeting the social communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorder in educational contexts. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00286-3.

Ona, H. N., Larsen, K., Nordheim, L. V., & Brurberg, K. G. (2020). Effects of Pivotal pivotal Response response Treatment treatment (PRT) for Children children with Autism autism Spectrum spectrum Disorders disorders (ASD): A Systematic systematic Reviewreview. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00180-z

Oono, I. P., Honey, E. J., & McConachie, H. (2013). Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(6), 2380–2479. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1952

*Oosterling, I., Visser, J., Swinkels, S., Rommelse, N., Donders, R., Woudenberg, T., ... & Buitelaar, J. (2010). Randomized controlled trial of the focus parent training for toddlers with autism: 1-year outcome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 40, 1447–1458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1004-0.

*Pajareya, K., & Nopmaneejumruslers, K. (2011). A pilot randomized controlled trial of DIR/Floortime™ parent training intervention for pre-school children with autistic spectrum disorders. Autism, 15(5), 563-577https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310386502.

Quinn, S., Donnelly, S., & Kidd, E. (2018). The relationship between symbolic play and language acquisition: A meta-analytic review. Developmental Review, 49, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.05.005

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

*Roberts, J., Williams, K., Carter, M., Evans, D., Parmenter, T., Silove, N., ... & Warren, A. (2011). A randomised controlled trial of two early intervention programs for young children with autism: Centre-based with parent program and home-based. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1553–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.001.

*Roberts, M. Y., Stern, Y. S., Grauzer, J., Nietfeld, J., Thompson, S., Jones, M., ... & Kaiser, A. P. (2023). Teaching caregivers to support social communication: Results from a randomized clinical trial of autistic toddlers. American journal of speech-language pathology, 32(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-22-00133.

*Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J., Fitzpatrick, A., ... & Dawson, G. (2012). Effects of a brief Early Start Denver Model (ESDM)–based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1052–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003.

*Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Munson, J., Rocha, M., Winter, J., ... & Talbott, M. (2019). A multisite randomized controlled two-phase trial of the Early Start Denver Model compared to treatment as usual. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(9), 853–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.01.004.

Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2005). Publication bias in meta‐analysis. Publication bias in meta‐analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470870168.

Rubin, K. H., Fein, G. G., & Vandenberg, B. (1983). Play. In P. H. Mussen & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology vol. 4 Socialization, personality, and social development (Vol. 4, pp. 693–774). Wiley.

Schertz, H. H., Liu, X., Odom, S. L., & Baggett, K. M. (2022). Parents’ application of mediated learning principles as predictors of toddler social initiations. Autism, 26(6), 1536–1549. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211061128

*Schertz, H. H., Odom, S. L., Baggett, K. M., & Sideris, J. H. (2013). Effects of joint attention mediated learning for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: An initial randomized controlled study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 249-258https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.06.006.

Shalev, R. A., Lavine, C., & Di Martino, A. (2020). A systematic review of the role of parent characteristics in parent-mediated interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-018-9641-x

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., ... & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj, 349. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647.

Shire, S. Y., Gulsrud, A., & Kasari, C. (2016). increasing responsive parent-child interactions and joint engagement: Comparing the influence of parent-mediated intervention and parent psychoeducation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(5), 1737–1747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2702-z

So, W.-C., Cheng, C.-H., Lam, W.-Y., Huang, Y., Ng, K.-C., Tung, H.-C., & Wong, W. (2020). A robot-based play-drama intervention may improve the joint attention and functional play behaviors of Chinese-speaking preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder: a pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04270-z

*Solomon, R., Van Egeren, L. A., Mahoney, G., Huber, M. S. Q., & Zimmerman, P. (2014). PLAY Project Home Consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(8), 475https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000096.

Stagnitti, K., O’Connor, C., & Sheppard, L. (2012). Impact of the Learn to Play program on play, social competence and language for children aged 5-8 years who attend a specialist school. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 59(4), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2012.01018.x