Abstract

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience social communication difficulties which can be compounded by increased social demands and expectations of the school environment. Play offers a unique context for social communication development in educational settings. This systematic review aimed to synthesize play-based interventions for the social communication skills of children with ASD in educational contexts and identified nine studies. Overall, studies in this review provided a promising evidence base for supporting social communication skills through play in education for children with ASD. The review also highlighted gaps in research on play-based interventions for the social communication skills of children with ASD within naturalistic educational settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social communication skills are a complex set of skills highlighted as difficult for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Balasubramanian et al., 2019; Howlin, 2000; Laugeson & Ellingsen, 2014). Social communication is an ‘umbrella term’, as described by Kossyvaki (2018, p.7), for both (1) social interaction, defined as the reciprocal exchange of information (Dijkstra, 2015; Shores, 1987) as well as relational components including relationships and friendships (Burk, 1996; Winstead & Derlega, 1986), acceptance and belonging (Duck & Montgomery, 1991; Goffman, 1963) and isolation and loneliness (Laursen & Harup, 2002; Samp, 2009), and (2) communication, defined as an interactive process in which information is exchanged between partners through multiple means such as body language, speech, facial expressions and gestures (Gould, 2009; Mehta, 1987; Nilsen, 1957; Rogoff, 1990; Schlosser, 2003). This inherent overlap between social interaction and communication is reflected within the literature (Conn, 2016; Fuller & Kaiser, 2019; Wetherby, 2006; Wetherby et al., 2007) and has been adopted within the latest diagnostic criteria for ASD (DSM-V) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As a result, this review will adopt an all-encompassing approach to social communication and include studies which target any aspect of social communication, in line with the above criteria.

Despite heterogeneity in the experiences and characteristics of individuals with ASD, challenges in social communication are experienced by all children across the spectrum (Anderson et al., 2014; APA, 2013; Balasubramanian et al., 2019; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2001) throughout all stages of life (Plimley et al., 2007; Prizant & Fields-Meyer, 2019; Tomaino et al., 2014; Volkmar et al., 2014) in areas including social-emotional reciprocity and non-verbal communication and in the development and understanding of relationships (APA, 2013). Differences are apparent from early infancy and include difficulties initiating (Franchini et al., 2018; Mundy et al., 2016; Sasson & Touchstone, 2014) and responding to joint attention (Chawarska et al., 2016; Sullivan et al., 2007) as well as differences in understanding non-verbal communication including eye contact (Muzammal & Jones, 2017; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2013), imitation (Ornstein-Davis & Carter, 2014; Rogers & Williams, 2006), body language, gestures and facial expression (Chawarska et al., 2014; Wetherby, 2006; Wetherby et al., 2004). Such differences often become more obvious among school-age children with ASD due to increased social demands (Bauminger-Zviely, 2014; Einfeld et al., 2018; Loveland & Tunali-Kotoski, 2005) in particular surrounding peer relations and include reduced levels of peer interactions (Bauminger-Zviely, 2014; Hansen et al., 2014; Wetherby, 2006) as well as quality (Bauminger et al., 2008; Kasari et al., 2011; Petrina et al., 2014) and quantity (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Kuo et al., 2013) of friendships and peer relationships.

As a result of these social communication challenges, children with ASD often remain on the periphery of classroom social networks (Chamberlain et al., 2007; Kasari et al., 2011; Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2010). Difficulties persist throughout the school years and extend into adolescence as children with ASD attempt to navigate the complex social world and subtle social cues of the hidden curriculum (Jordan, 2019; Myles & Simpson, 2001). These include differences forming and maintaining friendships (Bauminger & Shulman, 2003; Locke et al., 2010; Shea & Mesibov, 2005) and, in turn, associated loneliness (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Deckers et al., 2017; Lasgaard et al., 2010), bullying and victimization (Cappadocia et al., 2012; Symes & Humphrey, 2012; Van Roekel et al., 2010). Although schools may be regarded as the prime context for relationships to flourish (Blatchford et al., 2015; Blatchford et al., 2010; Juvonen, 2018), without sufficient support, such settings may in fact further isolate children with ASD.

Evidence of greater risk of increased social difficulties as children with ASD progress through formal schooling (Bauminger-Zviely, 2014) highlights the need for intervening early to support social communication development among children with ASD within educational contexts (Fuller & Kaiser, 2019; Koegel et al., 2014). Additionally, increasing numbers of children with ASD are accessing inclusive education (European Agency for Special Needs & Inclusive Education, 2018; National Council for Special Education, 2016) and spend the majority of their time in educational settings (Callahan et al., 2008; Parsons et al., 2013). As a result, research now emphasizes the importance of enhancing social communication skills of children with ASD within naturalistic educational contexts (Boyd et al., 2019; Goldberg et al., 2019; Sutton et al., 2019) which may also support generalization (Carruthers et al., 2020; Ostmeyer & Scarpa, 2012; Rao et al., 2008) and maintenance effects (Bellini et al., 2007; Neely et al., 2016; Rogers, 2000). Highly controlled clinical interventions may fail to capture authentic interactions within children’s everyday environment (Loveland, 2001; Loveland & Tunali-Kotoski, 2005) whereas a shift towards practice-based research (Barry et al., 2020; Boyd et al., 2019; Locke et al., 2019; Suhrheinrich et al., 2019) within a new ‘era of translational research’ (Boyd et al., 2019, p.595) in real-world educational settings allows for naturalistic peer interactions (Hume & Campbell, 2019; Kent et al., 2020b; Wolfberg, 2003) and, in turn, may close the research to practice gap (Guldberg, 2017; Kasari & Smith, 2013; Wood et al., 2015) and increase application to real-world contexts (Locke et al., 2015, 2019; Watkins et al., 2019a; Weisz et al., 2004).

One authentic context for social communication interactions embedded within the classroom is play (Balasubramanian et al., 2019; Reifel, 2014; Shire et al., 2020). Described as the primary medium of social interaction in early childhood (Boucher, 1999; Coelho et al., 2017; Harper et al., 2008), play offers a naturalistic platform for social communication development and learning within educational contexts. It has therefore been used as a practice-based intervention in supporting social communication skills for children with ASD. However, despite its centrality in early childhood, play is a multifaceted construct (Eberle, 2014; Sutton-Smith, 2001) which has been construed in different ways including objective criteria such as active engagement and open-endedness (Christie & Johnsen, 1983; Garvey, 1990; Rubin et al., 1983; Wolfberg, 1995, 1999) as well as subjective qualities described as playfulness (Barnett, 1990; Bundy, 1997; Eberle, 2014; Youell, 2008). Types of play include object play, symbolic or pretend play and games with rules (Piaget, 1952; Whitebread et al., 2012, 2017) as well as modern play types including digital play (Marsh et al., 2016). Others describe play in terms of social interaction with another, be it a peer, sibling, or adult (Parten, 1932; Vygotsky, 1978). Finally, play can also be defined in terms of the extent to which an adult is involved: for example, as free (no adult involvement), guided (adult is involved but child leads the play), or structured (adult directs the play interaction) (Rubin et al., 1978; Weisberg et al., 2016; Wood, 2014). As there is no single agreed-upon definition of play (Jensen et al., 2019; Zosh et al., 2018), for the purpose of this review all play-based approaches, self-identified by the relevant authors, were accepted.

Researchers have emphasized the potential of play in supporting the social communication skills of pupils with ASD within educational contexts (Jordan, 2003; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Manning & Wainwright, 2010; Wolfberg et al., 2015) and called for a move away from clinical settings (Guldberg, 2017; Papoudi & Kossyvaki, 2018, 2018; Whalon et al., 2015). Across varying contexts, the relationship between play and multiple aspects of social interaction has been highlighted including turn-taking and sharing (Anderson-McNamee & Bailey, 2010; Stanton-Chapman & Snell, 2011), collaboration (Rowe et al., 2018; White, 2012; Yogman et al., 2018), negotiation (Bergen & Fromberg, 2009; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2009; Mraz et al., 2016), social reciprocity (Carrero et al., 2014; Wolfberg, 1995) and theory of mind (Qu et al., 2015). Play also provides a natural context for the development of social relationships and has been described as children’s ‘natural means of making friends’ (Gray, 2011, p.457). Multiple researchers highlight the relationship between social play interactions and the development of friendships (Coelho et al., 2017; Humphreys & Smith, 1987; Scott & Panksepp, 2003) and peer acceptance (Chang et al., 2016a; Coelho et al., 2017; Flannery & Watson, 1993). The relationship between play and communication skills has also been identified including joint attention (Lillard & Witherington, 2004; Mateus et al., 2013; Quinn et al., 2018), joint engagement (Adamson et al., 2004, 2014; Moll et al., 2007; Perra & Gattis, 2012) and gestures and body language (Carlson, 2009; Cochet & Guidetti, 2018; Qing, 2011). Whilst much of the literature has focused on the relationship between pretend play and social communication development (Farmer-Dougan & Kaszuba, 1999; Fung & Cheng, 2017; Lillard et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016; Uren & Stagnitti, 2009; Vygotsky, 1978), in recent years there has been increasing consensus towards the socially interactive nature of many different types of play and their contribution to social communication development (Pellegrini et al., 2002; Veiga et al., 2017; Whitebread et al., 2017).

The Current Study

Previous reviews of the play of children with ASD have focused on the use of interventions to improve play skills (Jung & Sainato, 2013; Kent et al., 2020a; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Kuhaneck et al., 2020; Lang et al., 2011; Lory et al., 2018) or on the promotion of playful engagement among children with ASD (Godin et al., 2019) or therapeutic approaches such as Lego therapy (Lindsay et al., 2017). Fewer reviews have focused on play as a means to develop the social communication skills of children with ASD (Gibson et al., 2020; Mpella & Evaggelinou, 2018), and none have examined play-based interventions for social communication skills in educational contexts. For example, Gibson et al.’s (2020) scoping review of early play-based interventions for supporting social communication development of children with ASD, aged 2–7 years, found support for play in contributing to social developmental outcomes across multiple contexts. Our study contributes to the review literature on play-based interventions for the social communication skills of children with ASD (aged 3 to 13 years) by addressing an important gap on evidence synthesis of research conducted within the primary school classroom. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and synthesize research on play-based interventions for the social communication skills of children with ASD in educational contexts. The review was guided by four research questions: (1) What practice-based research has examined the impact of play-based interventions on the social communication skill development of children with ASD in educational contexts? (2) What are the characteristics of play-based interventions that target social communication skills of children with ASD in educational contexts? (3) What is the quality of research on play-based interventions for the social communication skills of children with ASD in educational contexts? and (4) What recommendations can be drawn from a review of the existing literature for future practice-based research in the field of autism, play and social communication development?

Methods

Protocol and Registration

The planning, organization and implementation of this systematic review was based on the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) and PRISMA-P statement (Shamseer et al., 2015). The review was pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FYEQS) to ensure transparency and reproducibility (Munafó et al., 2017; Sullivan et al., 2019) and reduce the risk of publication bias (van't Veer & Giner-Sorolla, 2016).

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the study reported empirical research (single-case or group research) examining the impact of play-based interventions on social communication skills; (2) play (self-defined by authors and included recognizable characteristics as outlined previously in this review) was identified as the independent variable and primary intervention; any additional strategies used in the intervention were supplementary and incorporated within the play session; (3) at least one outcome measure targeted social communication skills; (4) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal between the years 2000 and 2020; (5) participants included children, of primary-school age, between 3 and 13 years; (6) the sample population included at least one participant with a diagnosis of ASD; (7) data on dependent variables could be isolated for participants with and without ASD; (8) the study was conducted, at least partially, within educational contexts. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) the article was written in a language other than English; (2) the study design was a case study; (3) the play intervention was a form of play therapy; (4) participants included children outside of the pre-defined age range (3–13 years) who could not be isolated from the overall sample with regard to the effect of the intervention; and (5) play was used as part of a multi-component intervention approach alongside strategies including peer training sessions (e.g. Brock et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2018; Kamps et al., 2014; Katz & Girolametto, 2013; Kuhn et al., 2008; Laushey & Heflin, 2000; Lee et al., 2007; Maich et al., 2018; Thiemann-Bourque, 2012; Whitaker, 2004), direct teaching sessions (e.g. Szumski et al., 2016, 2019) or other naturalistic classroom activities including snack or toilet (e.g. Bauminger-Zviely et al., 2020; Boyd et al., 2018; Dykstra et al., 2012) or play was used as the context for the implementation of alternative interventions (e.g. Garfinkle & Schwartz, 2002; Harper et al., 2008; Owen-DeShryver et al., 2008; Simut et al., 2016). Single-case studies were excluded in order to reduce the risk of bias (Schünemann et al., 2013). Studies based on therapeutic interventions such as play therapy, Lego therapy and drama therapy were excluded given that these approaches are based on the therapeutic properties of play (Association for Play Therapy, 2020; Drews & Schaeffer, 2016) and extend beyond the definition of play in this review and have been systematically examined within other literature (Hillman, 2018; Lindsay et al., 2017).

Systematic Search Procedures

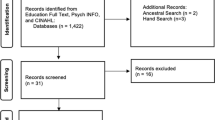

The search string was informed by key words and subject terms within sample seminal research in the field (Barber et al., 2016; Boyd et al., 2018; Chester et al., 2019; Dykstra et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2018; Kasari et al., 2012; Katz & Girolametto, 2013; Stagnitti et al., 2012; Vousden et al., 2019; Watkins et al., 2019b; Wolfberg et al., 2015; Wong, 2013; Yang et al., 2003), extensive pilot searching alongside subject librarian consultations and exploration of the thesaurus function across relevant databases. The final comprehensive search was conducted on 9 January 2020 across multiple academic databases including PsychInfo, CINAHL, Education Research Complete and ERIC. Searches across databases were based on the following identical search string: (‘Autism Spectrum Disorders’ OR ‘ASD’ OR Autis*) AND Play AND (‘Social Skills’ OR ‘Social Interaction’ OR ‘Social Communication’ OR ‘Social Competence’) AND (Education OR School* OR Class*). This process resulted in the return of 911 citations. Complementary backward chaining was also conducted given that database searching is not exhaustive (Evans & Benefield, 2001). The reference lists of the seminal articles identified (and listed) above were searched for eligible studies alongside the examination of the bibliographies of previous systematic reviews in the area (Alagendran et al., 2019; Cornell et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2020; Godin et al., 2019; Jung & Sainato, 2013; Kent et al., 2020a; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Kuhaneck et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2018; Lang et al., 2011; Lindsay et al., 2017; Lory et al., 2018; Mpella & Evaggelinou, 2018; Pyle et al., 2017). Overall, this process yielded an additional 130 citations resulting in a total of 1041 articles for potential inclusion. Finally, searches were re-run on 10 November 2020 to ensure all recently published material were included and the review was as current as possible, as recommended within the Cochrane guidelines (Lefebvre et al., 2020). This resulted in the inclusion of one additional full-text study based on eligibility criteria (Bauminger-Zviely et al., 2020). Following title and abstract screening, 88 studies were identified by the first author as meeting eligibility criteria. The full text of each article was then screened against the inclusion criteria which resulted in the identification of 29 full-text studies involving the use of play-based interventions to target the social communication skills of children, aged 3–13, with ASD within educational contexts. However, play was the primary independent variable in only nine of these interventions. As a result, the authors segregated these studies into (a) those that were multi-component interventions (i.e. play was one of several independent variables but was not the primary intervention variable) (n = 20) and (b) those that strictly met criteria for this review (n = 9). Figure 1 displays the results of each stage of the screening process.

Inter-Rater Reliability

Inter-rater coding was conducted throughout abstract and full-text screening stages. The first author screened all articles for inclusion. The second author blindly and independently screened 10% of the sample at the abstract stage and 20% at the full-text stage. Inter-rater agreement for inclusion was 84% when screening at the abstract stage and 100% when screening full texts in the final stage of the study search. Disagreements were resolved through discussions related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Narrative Synthesis

Data were extracted by the first author for the purpose of narrative synthesis. Studies included in this review were summarized in terms of: (1) participant characteristics including number, gender, age and diagnostic information; (2) research designs including design and types of methods used; and (3) intervention characteristics including components, frequency, intensity, duration, intervention setting, intervention agent, type of play, social communication outcomes and findings (three-point system outlined in the following section). Data were extracted and reported in tabular form, and a narrative synthesis of the extracted data was conducted to address the four research questions underpinning this systematic review. The second author blindly and independently extracted data from two of the nine selected texts (corresponding to 20% of the sample) according to identical characteristics. Inter-rater reliability was calculated and demonstrated 97% agreement, and discrepancies were solved through discussions.

Study Findings

A three-point classification system was used to indicate the type of findings from each study: positive, mixed or negative. A similar approach has been implemented across other systematic reviews where diversity of study designs has meant that it is difficult to compare study results (Gunning et al., 2019; Tupou et al., 2019; Verschuur et al., 2014). Single-case design studies were classified as positive if all participants demonstrated an increase across all social communication dependent variables, mixed if only some participants increased performance across social communication dependent variables and negative if no participant demonstrated an increase in any social communication dependent variables. Findings from group designs were classified as positive if statistically significant results were reported across all social communication dependent variables, mixed if statistically significant results were reported across some but not all social communication dependent variables and negative if no statistically significant results were reported across any social communication dependent variable.

Quality Appraisal

The quality of each study was assessed according to the Evaluative Method for Determining Evidence Based Practice in Autism (Reichow et al., 2008). This appraisal tool was selected given its specific reference to research within the field of autism, widespread use across other systematic reviews in the field (Ke et al., 2018; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Watkins et al., 2015) and reports of validity within the literature (Cicchetti, 2011; Wendt & Miller, 2012). Furthermore, the framework distinguishes between single-case and group research and was, thus, deemed suitable for the diverse range of research designs included in this review.

Single-case and group research studies were evaluated according to specific primary and secondary quality indicators including participant characteristics, clarity with which the independent variable was described, inter-observer agreement, fidelity, generalization and/or maintenance, and social validity. Studies subsequently received a quality rating of high, acceptable or unacceptable. Following this process, studies were categorized as strong, adequate or weak research. The first author independently evaluated all full-text reviews. The second author blindly and independently rated two of the nine selected texts (corresponding to 20% of sample) according to identical primary and secondary quality indicators. Inter-rater reliability was calculated and demonstrated 92% agreement. Discrepancies were solved through discussion as well as reference to the original documentation. The empirical strength of each study was categorized as promising or established based on the outcome of the quality rating process.

Results

Overall, a total of 29 full-text play-based interventions were identified following application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, only nine of these studies strictly met all eligibility criteria proposed within this review, specifically in relation to the use of play as the independent variable or primary intervention in improving social communication skills of children with ASD in educational settings. The remaining 20 articles used play as part of a multi-component social intervention package involving strategies outside of scheduled play sessions such as peer training, direct teaching and pre-teaching (see Table 1). As it was difficult to isolate the impact of play on social communication outcomes in these studies, they are excluded from the data extraction and narrative synthesis reported below.

Data on participant characteristics, study design and intervention characteristics were extracted from the nine eligible studies for inclusion and are first reported in tabular form (see Table 2). Data are further examined in narrative synthesis here.

Participant Characteristics

Overall, 107 children with ASD received treatment interventions within included studies with an additional 43 children with ASD included in wait-list control groups (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). The vast majority of research samples comprised of male participants with a total of 103 male and 16 female participants included across studies, with the exception of Goods et al. (2013) and Lawton and Kasari (2012) who did not report sample participants’ gender. Overall, the age range of participants was 3 to almost 13 years with a mean age of approximately 6.21 years (this is approximate as some studies did not specify age in months). This does not include participants within Thomas and Smith’s (2004) study given that information was only provided in relation to age range as opposed to mean. All participants had a professional diagnosis of ASD with some studies reporting IQ levels (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005), mental age scores (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012) or severity of ASD (Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Watkins et al., 2019b). Five of the studies excluded respondents with co-occurring needs (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005); however, it is unclear if the remaining interventions included children with co-occurring needs.

Play-Based Intervention Characteristics

Play-based interventions were employed as the independent variable across all nine full-text studies. Play-based interventions varied in their presentation across studies in terms of social partners, types of play used and level of child autonomy and adult involvement. This is unsurprising based on the multi-faceted nature of play. Given the focus on social communication outcomes, all studies involved social play, ranging from play with a single peer (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Watkins et al., 2019b) to play in peer groups (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Vincent et al., 2018) and play with adults (Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004) as well as the combination of both adult and peer play (Chang et al., 2016b) with the exception of Goods et al. (2013) whereby it is unclear whether adult play was combined with peer play. Furthermore, studies varied in their approach to peer play with some interventions employing peers with ASD (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005) and others utilizing typically developing peers (Chang et al., 2016b; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b). The majority of play sessions involved a semi-structured or guided play approach and balance between adult and child agency (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) whilst others focused on adult-led structured play (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004). Although Watkins et al. (2019b) described their play intervention as structured, it involved minimal adult direction and was very much child-led and has consequently been classified as a semi-structured or guided play approach within this review. Finally, the majority of studies adopted an individualized approach to play whereby play types were often selected based on the developmental level of the child (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012) as well as the incorporation of interests and preferences within object play (Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al., 2019b) or game play (Vincent et al., 2018). Chang et al. (2016b) implemented multiple types of play (cause and effect or object play, functional and symbolic play) with a similar approach adopted across other play-based interventions (Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). Although Goods et al. (2013) or Lawton and Kasari (2012) do not specify types of play employed, reference is made to previous publications which clearly indicate types of play used (object, functional and symbolic play) which are shown in Table 2. The remaining studies focused specifically on symbolic or imaginative play (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005) and digital play (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012).

Play-based intervention programs were employed across all nine full-text articles included within this review, for example JASPER (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012), as well as individualized adapted interventions (Watkins et al., 2019b). Despite heterogeneity in approaches to play, none of the nine studies explicitly discussed or stated the theory of play which underpinned the intervention. However, upon examination of theoretical underpinnings based on intervention components, the majority of studies were based on naturalistic behavioural approaches (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018). These approaches combine behavioural and developmental principles within a natural context (Schreibman et al., 2015; Tiede & Walton, 2019), in this case through play interactions. Naturalistic behavioural approaches also combine traditional behavioural components including adult modelling (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018), imitation (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004), prompting (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Vincent et al., 2018), positive reinforcement (Goods et al., 2013; Vincent et al., 2018) and visual supports (Thomas & Smith, 2004) with developmental approaches including individualized strategies and support (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013), incorporation of interests and preferences (Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012) and environmental arrangement (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Vincent et al., 2018). Watkins et al. (2019b) also drew on such developmental approaches involving individualization of play sessions and use of children’s interests. Finally, Beadle-Brown et al.’s (2018) intervention was child-led which incorporated immersive environments, multiple stimuli and scenario based learning whilst Loncola and Craig-Unkefer (2005) employed a social cognitive approach involving instruction of social behaviours, rehearsal or repeated practice, feedback and reinforcement of social behaviours as well as skill maintenance and generalization.

Characteristics of the Educational Contexts for Play-Based Interventions

All nine studies conducted play-based interventions within educational settings, as stipulated within the eligibility criteria. Three of the nine studies were carried out within special schools (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Goods et al., 2013; Watkins et al., 2019b) with the remaining interventions conducted within mainstream schools (Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018) and special classes (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2016b; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). Four of the interventions were conducted within authentic classroom play areas (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Watkins et al., 2019b) whilst the remaining four studies were implemented outside of the classroom context within an area of the school hallway (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005), isolated quiet room (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012) or playground recess (Vincent et al., 2018) with the exception of Thomas and Smith’s study (2004) whereby the context of the intervention is not specified. Selected studies were carried out across a limited range of geographical locations including the USA (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) UK (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Thomas & Smith, 2004) and Israel (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012). Although all studies were conducted within educational settings, only two of the nine included interventions employed existing school teachers or paraprofessionals as interventionists (Chang et al., 2016b; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). The remaining studies involved members of the research team (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al., 2019b) or trained independent interventionists (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Goods et al., 2013; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018).

Intervention Characteristics Regarding Frequency, Intensity and Duration

Play-based interventions ranged from daily intervention techniques (Chang et al., 2016b; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) to weekly (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018), two times weekly (Goods et al., 2013), three times weekly (Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005) or twice monthly (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012). Interventions also varied in terms of the intensity of intervention sessions from 5–10 min (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al., 2019b) to 15–20 min (Chang et al., 2016b; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018) and 30–45 min (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). The average intensity of intervention was 21 min with the exception of Ben-Sasson et al. (2012) who did not specify intervention intensity. The duration of intervention periods also varied widely from a minimum of 2 weeks (Thomas & Smith, 2004) to a maximum of 34 weeks (Vincent et al., 2018).

Type of Social Communication Outcomes Targeted

All nine full-text reviews targeted social communication outcomes, as stipulated within eligibility criteria. The majority of studies provided a clear operational definition of target outcomes based on the measurement of social initiations (Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) and responses (Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Watkins et al., 2019b) by target participants with ASD towards peers or adults within play. Ben-Sasson et al. (2012) also examined the frequency of positive and negative social interactions alongside social responsive scales whilst other studies focused specifically on initiations of joint attention behaviours (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). However, social communication outcomes were less clear within some studies (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Thomas & Smith, 2004) in particular when dependent measures were based on generic social communication subscales (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018) and social interaction (Thomas & Smith, 2004).

Given that social communication skills did not have to be the exclusive outcome, eight of the nine included studies incorporated additional outcome measures. These included evaluation of teacher implementation of play-based interventions (Chang et al., 2016b; Lawton & Kasari, 2012); impact of play-based interventions on additional areas of development including language skills (Chang et al., 2016b; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005), play behaviours (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al., 2019b), cognitive skills (Chang et al., 2016b) and the effect of interventionist support during play-based interventions (Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005); and impact of the level of social communication deficits on intervention outcomes (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012).

Study Findings

Results of studies were classified as positive, mixed or negative as outlined in ‘Methods’. Two single-case design studies reported an increase in all social and communication outcomes across all participants and were thus classified as providing positive findings (Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al., 2019b) with a further group research study also exhibiting significant findings across all social communication dependent variables (Chang et al., 2016b). The remainder of study outcomes were classified as mixed due to demonstration of positive results across some but not all participants (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018) or across some but not all social communication dependent variables (Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012).

Study Quality

The quality of included articles was examined using Reichow et al.’s (2008) evaluative framework; however, studies were not excluded based on evaluations of rigor. Given the limited research in this area, each of these studies was valuable in contributing to the evidence base. However, the majority of studies were classified as weak based on primary and secondary quality indicators (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004) with the remainder classified as adequate (Chang et al., 2016b; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b). Following implementation of Reichow et al.’s (2008) criteria, play-based interventions are regarded as a promising evidence-based practice given identification of at least three single-subject or at least two group experimental designs of at least adequate research report strength, conducted by at least two different research teams in at least two different locations, involving a total sample size of at least nine different participants across studies.

Generalization, Maintenance and Social Validity

According to Reichow et al.’s (2008) criteria, two of the included full texts collected data on generalization of social communication outcomes within free-play sessions (Chang et al., 2016b) and as part of a formal generalization assessment (Goods et al., 2013). A further three studies implemented generalization measures (Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al. 2019b) however, these were implemented throughout the intervention as opposed to upon its completion, as stipulated within Reichow et al.’s (2008) criteria. Watkins et al. (2019b) measured generalization of social communication skills to novel peer partners. In addition, Thomas and Smith (2004) incorporated generalization measures to ascertain the generalization of play behaviours to free-play contexts and Lawton and Kasari (2012) examined teachers’ generalization of JASPER strategies within the classroom. Three of the included studies also completed maintenance measures following the termination of the intervention. Watkins et al. (2019b) conducted follow-up sessions 6 weeks post-intervention whilst Chang et al. (2016b) conducted a 1-month follow-up assessment and Beadle-Brown et al. (2018) conducted three follow-up sessions up to 12 months post-intervention. Watkins et al. (2019b) was the only study to explicitly collect data in relation to social validity based on classroom teacher evaluations, comparisons with typically developing peers and observer ratings. However, using Reichow et al.’s (2008) criteria for social validity, a further five studies included at least four out of seven social validity measures (Ben-Sasson et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b). These related to socially important outcomes, comparisons conducted between individuals with and without disabilities, clinically significant target behaviour, consumer satisfaction with the results, implementation in natural contexts and by those who typically come into contact with participants and time and cost effectiveness (ends justified the means) of the intervention. Finally, treatment or procedural fidelity was reported by the majority of included studies using pre-defined checklists and criteria with statistical tests all reaching 80% or over, as stipulated within Reichow et al.’s (2008) criteria (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b). Table 3 presents a summary of results based on Reichow et al.’s (2008) criteria for generalization, maintenance, social validity and fidelity.

Recommendations for Future Practice-Based Research in the Field of Autism, Play and Social Communication Development

This review identified nine promising research studies on play-based interventions in supporting social communication skills of children with ASD within education contexts, a field very much in its infancy. There are several implications for future research in this area. Firstly, future research should explicitly report participant characteristics including IQ, functioning levels and presence of co-occurring needs in order to ascertain if results can generalize across all students with ASD given the heterogeneity of the spectrum, as recommended within similar reviews (Gibson et al., 2017, 2020; Hansen et al., 2017; Kent et al., 2020a; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016). Secondly, although all studies were conducted within educational contexts, future practice-based research may benefit from examining play-based interventions as part of classroom practice as opposed to isolated educational settings, as recommended within previous systematic reviews in the field (Bellini et al., 2007; Hansen et al., 2017; Jung & Sainato, 2013; Kent et al., 2020a) and broader research literature (Kasari & Smith, 2013; Koegel et al., 2012; Laugeson et al., 2014; Mazurik-Charles & Stefanou, 2010). Given the diversity and heterogeneity of the classroom environment, this will also enable researchers to identify the influence of contextual variables such as inclusive classroom practices (Woodman et al., 2016), teacher support (Pintrich et al., 1993) and activity types (Vitiello et al., 2012) on social communication outcomes (Gibson et al., 2017; Hume et al., 2019; Kent et al., 2020a). Furthermore, further research is needed to examine the role of educators as interventionists in play-based interventions, as previously recommended (Bellini et al., 2007; Hansen et al., 2017; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016). In addition, future research should incorporate measures of generalization and maintenance, in line with previous reviews in the field (Brady et al., 2020; Gunning et al., 2019; Hansen et al., 2017; Kent et al., 2020a). This is especially important given the reported generalization (Carruthers et al., 2020; Ostmeyer & Scarpa, 2012; Rao et al., 2008) and maintenance (Bellini et al., 2007; Neely et al., 2016; Rogers, 2000) benefits of practice-based research. Thirdly, future research should consider seeking input from teachers, peers and also children with ASD, as reflected within broader participatory research recommendations (den Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Houting et al., 2020; Jivraj et al., 2014; Lau & Stille, 2014) and, consequently, add to the social validity of this evidence base. Fourthly, given that the vast majority of play-based interventions included in this review were based on predominately male samples across the UK and USA, future research may consider including more geographical and gender representative samples, as identified within other systematic reviews in the field (Gibson et al., 2020; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Stiller & Mößle, 2018). Fifthly, using Reichow et al.’s (2008) quality criteria, the vast majority of studies in this review were classified as weak or adequate. This finding supports recommendations by Gibson et al. (2020) in their recent scoping review of play-based interventions to support social communication development of children, aged 2–7, with ASD in which they highlighted the need for increased rigor in research on play-based interventions for the social communicative development of children with ASD. Finally, given the multi-faceted nature of both play and social communication, future research should provide an account of the theoretical approaches underpinning the play interventions, as recommended within similar reviews (Gibson et al., 2020; Ke et al., 2018; Lindsay et al., 2017).

Discussion

The present review aimed to identify practice-based research on play-based interventions for the social communication skills of children with ASD in educational contexts. The relationship between play and social communication development within early childhood education is widely recognized (Barnett, 2018; Beazidou & Botsoglou, 2016; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2009). However, this is an emerging field for children with ASD, as reflected in the results of this review whereby a total of just nine studies were identified, with seven of these studies conducted in the last 8 years.

Research on Play-Based Interventions for the Social Communication Skills of Children with ASD in Educational Settings

Play-based interventions varied widely in terms of intervention characteristics, for example, in types and contexts of play, social communication measures, settings, intensity, frequency, duration and intervention agents. There were, however, commonalities across studies including the selection of types of play and materials based on children’s developmental level or interests (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b), in line with research recommendations (Jordan, 2003; Kasari et al., 2006; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Papoudi & Kossyvaki, 2018). Guided play appeared to form a key part of play-based interventions with the majority of studies involving adult involvement and child autonomy (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Vincent et al., 2018), reflecting broader recommendations in terms of the provision of support during play for children with ASD (Kok et al., 2002; Papoudi & Kossyvaki, 2018, 2018; Sherratt & Peter, 2002; Wolfberg et al., 2012). This also aligns with increasing emphasis on the importance of guided play in educational contexts in order to support learning and development (Weisberg et al., 2013, 2016; Yu et al., 2018; Zosh et al., 2017, 2018). The majority of studies incorporated authentic peers within play-based interventions (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2016b; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b), a key benefit of conducting research within educational contexts (Hume & Campbell, 2019; Kent et al., 2020b; Wolfberg, 2003). These included both typically developing peers (Chang et al., 2016b; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) and peers with ASD (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005), with the selection of peers often dependent on the nature of the educational setting.

Although play-based interventions across all studies involved a social element, they varied greatly in terms of the varieties of play employed from object play (Thomas & Smith, 2004; Watkins et al., 2019b) and game play (Vincent et al., 2018) to symbolic or imaginative play (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005) and digital play (Ben-Sasson et al., 2012) highlighting the potential value of all types of play in supporting social communication outcomes (Pellegrini et al., 2002; Veiga et al., 2017; Whitebread et al., 2017).

Commonalities were evident across targeted social communication outcomes specifically frequency of social initiations and responses (Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) alongside joint attention and engagement (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012). This is surprising given the vast array of social communication skills associated with play for typically developing children including turn-taking and sharing (Anderson-McNamee & Bailey, 2010; Stanton-Chapman & Snell, 2011), collaboration (Rowe et al., 2018; White, 2012; Yogman et al., 2018), negotiation (Bergen & Fromberg, 2009; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2009; Mraz et al., 2016), theory of mind (Qu et al., 2015) and relational components such as friendships (Coelho et al., 2017; Humphreys & Smith, 1987; Scott & Panksepp, 2003) and peer acceptance (Coelho et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2016a; Flannery & Watson, 1993) as well as communication outcomes such as gestures and body language (Carlson, 2009; Cochet & Guidetti, 2018; Qing, 2011), all skills in which children with ASD may benefit from assistance and support.

Finally, the majority of studies consisted of naturalistic behavioural approaches (e.g. Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018) similar to findings reported in other systematic reviews in the field (Gibson et al., 2020; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016). This is unsurprising given the current shift within the literature towards an integrated approach to learning involving both behavioural and developmental approaches for children with ASD (Frost et al., 2020; Hume et al., 2021; Schreibman et al., 2015). However, with the exception of Loncola and Craig-Unkefer (2005), philosophies were inferred in this review from the strategies and approaches used, thus highlighting the need to report on theoretical underpinnings going forward within future research, as recommended by Vivanti (2017).

Implications for Practice in the field of Autism, Play, and Social Communication Development

Given that this review focused on examining play-based interventions for social communication of children with ASD in educational contexts, findings can offer unique practical implications. Although findings are not conclusive, they demonstrate promising evidence for the potential of play for social communication of children with ASD that extend beyond the clinical context and offer support to those currently implementing play within the classroom, of particular importance given the international promotion of play-based curricula (Aistear, Enriched Curriculum/Early Years Foundation, High/Scope, Reggio Emilia, Te Whãriki) and increasing endorsement of play within education for children with ASD (Jordan, 2003; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, 2016; Manning & Wainwright, 2010; Papoudi & Kossyvaki, 2018, 2018; Wolfberg et al., 2015). However, given the diversity of interventions included, it proves difficult to evaluate how best to use play to support social communication skills of children with ASD in terms of intervention setting, intensity, frequency, duration and intervention agents. There are however commonalities across included play-based interventions which may offer guidance for practitioners in the field including consideration of the child’s developmental level and interests (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b), use of guided play or adult support and involvement during play (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Vincent et al., 2018) and involvement of authentic peers (Beadle-Brown et al., 2018; Ben-Sasson et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2016b; Loncola & Craig-Unkefer, 2005; Vincent et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2019b) as well as the potential value of naturalistic developmental approaches (Chang et al., 2016b; Goods et al., 2013; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Thomas & Smith, 2004; Vincent et al., 2018). Further research involving practitioners is very much warranted in order to fully determine the feasibility and effectiveness of practitioner-implemented play-based interventions within educational contexts and work towards bridging the gap between research and practice (Guldberg, 2017; Hume et al., 2021; Kasari & Smith, 2013; Wood et al., 2015).

Limitations

This review offers a unique and timely insight into current practice-based evidence surrounding the impact of play on the social communication outcomes of children with ASD within educational contexts. There are, however, several limitations which need to be acknowledged. Firstly, a diverse range of study types were included involving both single-case and group research which restricted subsequent analysis to narrative synthesis as opposed to meta-analysis. Although this allowed for an overview of relevant studies to be synthesized, it prevented effective comparisons to be drawn between research; thus, the extent to which play-based interventions impacted social communication skills is unknown. Secondly, studies were only included if they met strict eligibility criteria. As a result, it is possible that meaningful papers were excluded that did not fit these specific criteria. Whilst every effort was made to conduct searches across multiple databases and types, including the implementation of hand searching and updated follow-up searches, this search was not exhaustive and it is not possible to ensure all relevant studies were included. Thirdly, quality appraisal was conducted based on strict interpretation of criteria outlined by Reichow et al. (2008). This was selected following careful consideration of quality frameworks given the diverse range of single-case and group research included in this review. However, appraisal ratings were based on the level of detail outlined within studies and it is possible details may have been omitted which subsequently may have influenced appraisal ratings. In addition, such studies may have received alternative ratings if different appraisal tools were selected.

Conclusion

Overall, this review identified the emerging evidence base of practice-based research that has examined the potential of play-based interventions in supporting the social communication outcomes of children with ASD within educational contexts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate the impact of play on the social communication skills of children with ASD in naturalistic educational contexts. As a result, this review significantly contributes to the emerging literature surrounding practice-based research in supporting the social communication development of children with ASD (Barry et al., 2020; Boyd et al., 2019; Locke et al., 2019) and, in particular, provides support for the potential of play-based interventions in contributing to the social communication skills of children with ASD within educational contexts as part of a new ‘era of translational research’ (Boyd et al., 2019, p.595). This is important given the increasing number of children with ASD accessing inclusive education (European Agency for Special Needs & Inclusive Education, 2018; National Council for Special Education, 2016) and associated demands and expectations of formal schooling (Bauminger-Zviely, 2014; Einfeld et al., 2018; Loveland & Tunali-Kotoski, 2005). However, as highlighted by the limited number of studies in this review, there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding the mechanisms by which play-based interventions might be especially beneficial for the social communication skills of children with ASD in educational contexts. Further rigorous research is warranted to expand on this emerging evidence base.

References

*Study included in the review

Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., & Deckner, D. F. (2004). The development of symbol-infused joint engagement. Child Development, 75(4), 1171–1187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00732.x

Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Deckner, D. F., & Nelson, P. B. (2014). From interactions to conversations: The development of joint engagement during early childhood. Child Development, 85(3), 941–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12189

Alagendran, K., Hitch, D., Wadley, C., & Stagnitti, K. (2019). Cortisol responsivity to social play in children with autism: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 12(4), 427–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2019.1604285

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; DSM-V (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, D. K., Liang, J. W., & Lord, C. (2014). Predicting young adult outcome among more and less cognitively able individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(5), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12178

Anderson-McNamee, J.K. & Bailey, S.J. (2010). The importance of play in early childhood development. Montana State University Extention, http://msuextension.org/publications/HomeHealthandFamily/MT201003HR.pdf. Accessed 9 Jun 2020

Association for Play Therapy (2020). What is play therapy. Association for Play https://www.a4pt.org/ Accessed 4 Dec 2020

Balasubramanian, L., Blum, A. M., & Wolfberg, P. (2019). Building on early foundations into school: Fostering socialization in meaningful socio-cultural contexts. In R. Jordan, J. M. Roberts, & K. Hume (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of autism and education (pp. 134–253). Sage.

Barber, A. B., Saffo, R. W., Gilpin, A. T., Craft, L. D., & Goldstein, H. (2016). Peers as clinicians: Examining the impact of Stay Play Talk on social communication in young preschoolers with autism. Journal of Communication Disorders, 59, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2015.06.009

Barnett, L. A. (1990). Playfulness: Definition, design, and measurement. Play & Culture, 3, 319–336.

Barnett, J. H. (2018). Three evidence-based strategies that support social skills and play among young children with autism spectrum disorders. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(6), 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-018-0911-0

Barry, L., Holloway, J., & McMahon, J. (2020). A scoping review of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of interventions in autism education. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 78, 101617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101617

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71(2), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00156

Bauminger, N., & Shulman, C. (2003). The development and maintenance of friendship in high-functioning children with autism: Maternal perceptions. Autism, 7(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361303007001007

Bauminger, N., Solomon, M., Aviezer, A., Heung, K., Gazit, L., Brown, J., & Rogers, S. J. (2008). Children with autism and their friends: A multidimensional study of friendship in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9156-x

Bauminger-Zviely, N., et al. (2014). School age children with ASD. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (4th ed., pp. 148–175). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

Bauminger-Zviely, N., Eytan, D., Hoshmand, S., & Ben-Shlomo, O. R. (2020). Preschool peer social intervention (PPSI) to enhance social play, interaction, and conversation: Study outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 844–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04316-2

*Beadle-Brown, J., Wilkinson, D., Richardson, L., Shaughnessy, N., Trimingham, M., Leigh, J., Whelton, B. & Himmerich, J. (2018). Imagining autism: Feasibility of a drama-based intervention on the social, communicative and imaginative behavior of children with autism. Autism, 22(8), 915–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317710797

Beazidou, E., & Botsoglou, K. (2016). Peer acceptance and friendship in early childhood: The conceptual distinctions between them. Early Child Development and Care, 186(10), 1615–1631. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1117077

Bellini, S., Peters, J. K., Benner, L., & Hopf, A. (2007). A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 28(3), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280030401

*Ben-Sasson, A., Lamash, L. & Gal, E. (2013). To enforce or not to enforce? The use of collaborative interfaces to promote socialskills in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 17(5), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312451526

Bergen, D., & Fromberg, D. P. (2009). Play and social interaction in middle childhood. Phi Delta Kappan, 90(6), 426–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170909000610

Blatchford, P., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2010). Peer relations in school. In K. Littleton, C. Wood, & J. K. Staarman (Eds.), International handbook of psychology in education (pp. 227–274). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Blatchford, P., Pellegrini, A. D., & Baines, E. (2015). The child at school: Interactions with peers and teachers. Routledge.

Boucher, J. (1999). Editorial: Interventions with children with autism – Methods based on play. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 15, 1–5.

Boyd, B. A., Watson, L. R., Reszka, S. S., Sideris, J., Alessandri, M., Baranek, G. T., Crais, E. R., Donaldson, A., Gutierrez, A., Johnson, L., & Belardi, K. (2018). Efficacy of the ASAP intervention for preschoolers with ASD: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(9), 3144–3162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3584-z

Boyd, B. A., Dykstra Steinbrenner, J. R., Reszka, S. S., & Carroll, A. (2019). Research in autism education: Current issues and future directions. In R. Jordan, J. Roberts, & K. Hume (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of autism and education (pp. 595–605). SAGE.

Brady, R., Maccarrone, A., Holloway, J., Gunning, C. & Pacia, C. (2020). Exploring interventions used to teach friendship skills to children and adolescents with high-functioning autism: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00194-7

Brock, M. E., Dueker, S. A., & Barczak, M. A. (2018). Brief report: Improving social outcomes for students with autism at recess through peer-mediated pivotal response training. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(6), 2224–2230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3435-3

Bundy, A. (1997). Play and playfulness: What to look for. In L. D. Parham & L. S. Fazio (Eds.), Play in occupational therapy for children (pp. 52–66). Elsevier.

Burk, D. I. (1996). Understanding friendship and social interaction. Childhood Education, 72(5), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.1996.10521867

Callahan, K., Henson, R. K., & Cowan, A. K. (2008). Social validation of evidence-based practices in autism by parents, teachers, and administrators. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(4), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0434-9

Cappadocia, M. C., Weiss, J. A., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x

Carlson, F. (2009). Rough and tumble play. Exchange, 188, 70–73.

Carrero, K. M., Lewis, C. G., Zolkoski, S., & Lusk, M. E. (2014). Research based strategies for teaching play skills to children with autism. Beyond Behavior, 23(3), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/107429561402300304

Carruthers, S., Pickles, A., Slonims, V., Howlin, P., & Charman, T. (2020). Beyond intervention into daily life: A systematic review of generalization following social communication interventions for young children with autism. Autism Research, 13(4), 506–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2264

Chamberlain, B., Kasari, C., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2007). Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4

Chang, Y. C., Shih, W., & Kasari, C. (2016a). Friendships in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder: What holds them back, child characteristics or teacher behavior? Autism, 20(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314567761

*Chang, V.C., Shire, S.Y., Shire, W., Gelfand, C. & Kasari, C. (2016b). Preschool deployment of evidence-based social communication intervention: JASPER in the classroom, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2211–2223https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2752-2

Chawarska, K., Macari, S., Volkmar, F. R., Kim, S. H., & Shic, F., et al. (2014). ASD in infants and toddlers. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (4th) (pp. 121–147). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

Chawarska, K., Ye, S., Shic, F., & Chen, L. (2016). Multilevel differences in spontaneous social attention in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Child Development, 87(2), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12473

Chester, M., Richdale, A. L., & McGillivray, J. (2019). Group-based social skills training with play for children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2231–2242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03892-7

Christie, J. F., & Johnsen, E. P. (1983). The role of play in social-intellectual development. Review of Educational Research, 53(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543053001093

Cicchetti, D. V. (2011). On the reliability and accuracy of the evaluative method for identifying evidence-based practices in autism. In B. Reichow, P. Doehring, D. V. Cicchetti, & F. R. Volkmar (Eds.), Evidence-based practices and treatments for children with autism (pp. 41–51). Springer.

Cochet, H., & Guidetti, M. (2018). Contribution of developmental psychology to the study of social interactions: Some factors in play, joint attention and joint action and implications for robotics. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01992

Coelho, L., Torres, N., Fernandes, C., & Santos, A. J. (2017). Quality of play, social acceptance and reciprocal friendship in preschool children. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(6), 812–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1380879

Conn, C. (2016). Observation, assessment and planning in inclusive Autism education: Supporting learning and development. Routledge.

Cornell, H. R., Lin, T. T., & Anderson, J. A. (2018). A systematic review of play-based interventions for students with ADHD: Implications for school-based occupational therapists. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(2), 192–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1432446

Deckers, A., Muris, P., & Roelofs, J. (2017). Being on your own or feeling lonely? Loneliness and other social variables in youths with autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48(5), 828–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0707-7

Dijkstra, J. (2015). Social exchange: Relations and networks. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 5(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-015-0301-1

Drews, A. A., & Schaefer, C. E. (2016). The therapeutic powers of play. In K. J. O’Connor, C. E. Schaefer, & L. D. Braverman (Eds.), Handbook of play therapy, (2nd) (pp. 35–60). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

Duck, S., & Montgomery, B. M. (1991). The interdependence among interaction substance, theory and methods. In B. M. Montgomery & S. Duck (Eds.), Studying interpersonal interaction (pp. 3–15). Guilford Press.

Dykstra, J. R., Boyd, B. A., Watson, L. R., Crais, E. R., & Baranek, G. T. (2012). The impact of the Advancing Social-communication and Play (ASAP) intervention on preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 16(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311408933

Eberle, S. G. (2014). The elements of play: Toward a philosophy and a definition of play. American Journal of Play, 6(2), 214–233.

Einfeld, S. L., Beaumont, R., Clark, T., Clarke, K. S., Costley, D., Gray, K. M., Horstead, S. K., Redoblado Hodge, M. A., Roberts, J., Sofronoff, K., & Taffe, J. R. (2018). School-based social skills training for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1326587

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018). European agency statistics on inclusive education: 2018 dataset cross-country report, https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/european-agency-statistics-inclusive-education-2018-dataset-cross-country. Accessed 10 Mar 2020

Farmer-Dougan, V., & Kaszuba, T. (1999). Reliability and validity of play-based observations: Relationship between the PLAY behavior observation system and standardised measures of cognitive and social skills. Educational Psychology, 19(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341990190404

Flannery, K. A., & Watson, M. W. (1993). Are individual differences in fantasy play related to peer acceptance levels? The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 154(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1993.10532194

Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., Leekam, S., Milton, D., Parr, J. R., & Pellicano, E. (2019). Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism, 23(4), 943–953. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721

Franchini, M., Duku, E., Armstrong, V., Brian, J., Bryson, S. E., Garon, N., Roberts, W., Roncadin, C., Zwaigenbaum, L., & Smith, I. M. (2018). Variability in verbal and nonverbal communication in infants at risk for autism spectrum disorder: Predictors and outcomes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(10), 417–3431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3607-9

Frost, K. M., Brian, J., Gengoux, G. W., Hardan, A., Rieth, S. R., Stahmer, A., & Ingersoll, B. (2020). Identifying and measuring the common elements of naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for autism spectrum disorder: Development of the NDBI-Fi. Autism, 24(8), 2285–2297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320944011

Fuller, E. A. & Kaiser, A. P. (2019). The effects of early intervention on social communication outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–18.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03927-z

Fung, W. K., & Cheng, R. W. Y. (2017). Effect of school pretend play on preschoolers’ social competence in peer interactions: Gender as a potential moderator. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0760-z

Garfinkle, A. N., & Schwartz, I. S. (2002). Peer imitation: Increasing social interactions in children with autism and other developmental disabilities in inclusive preschool classrooms. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F027112140202200103

Garvey, C. (1990). The modals of necessity and obligation in children’s pretend play. Play & Culture, 3(3), 206–218.

Gibson, J. L., Cornell, M., & Gill, T. (2017). A systematic review of research into the impact of loose parts play on children’s cognitive, social and emotional development. School Mental Health, 9(4), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9220-9

Gibson, J. L., Pritchard, E. J., & de Lemos, C. (2020). Play-based interventions to support social and communication development in autistic children aged 2–8 years: A scoping review., PsyArXiv, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mp2xc

Godin, J., Freeman, A., & Rigby, P. (2019). Interventions to promote the playful engagement in social interaction of preschool-aged children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A scoping study. Early Child Development and Care, 189(10), 1666–1681. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1404999

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

Goldberg, J. M., Sklad, M., Elfrink, T. R., Schreurs, K. M., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Clarke, A. M. (2019). Effectiveness of interventions adopting a whole school approach to enhancing social and emotional development: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(4), 755–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0406-9

*Goods, K. S., Ishijima, E., Chang, Y. C. & Kasari, C. (2013). Preschool based JASPER intervention in minimally verbal children with autism: Pilot RCT, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1050–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1644-3

Gould, J. (2009). There is more to communication than tongue placement and ‘show and tell’: Discussing communication from a speech pathology perspective. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 29(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268600802516384

Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Play, 3(4), 443–463

Guldberg, K. (2017). Evidence-based practice in autism educational research: Can we bridge the research and practice gap. Oxford Review of Education, 43(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2016.1248818

Gunning, C., Breathnach, Ó., Holloway, J., McTiernan, A., & Malone, B. (2019). A systematic review of peer-mediated interventions for preschool children with autism spectrum disorder in inclusive settings. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(1), 40–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-018-0153-5

Hansen, S. G., Blakely, A. W., Dolata, J. K., Raulston, T., & Machalicek, W. (2014). Children with autism in the inclusive preschool classroom: A systematic review of single-subject design interventions on social communication skills. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(3), 192–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0020-y

Hansen, S. G., Frantz, R. J., Machalicek, W., & Raulston, T. J. (2017). Advanced social communication skills for young children with autism: A systematic review of single-case intervention studies. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4(3), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-017-0110-8

Harper, C. B., Symon, J. B., & Frea, W. D. (2008). Recess is time-in: Using peers to improve social skills of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0449-2

Hillman, H. (2018). Child-centered play therapy as an intervention for children with autism: A literature review. International Journal of Play Therapy, 27(4), 198. https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000083

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Berk, L. E., & Singer, D. (2009). A mandate for playful learning in preschool: Applying the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press.

den Houting, J., Higgins, J., Isaacs, K., Mahony, J. & Pellicano, E., 2020. ‘I’m not just a guinea pig’: Academic and community perceptions of participatory autism research. Autism,1–16, https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320951696

Howlin, P. (2000). Outcome in adult life for more able individuals with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism, 4(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361300004001005

Hu, X., Zheng, Q., & Lee, G. T. (2018). Using peer-mediated LEGO® play intervention to improve social interactions for Chinese children with autism in an inclusive setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(7), 2444–2457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3502-4

Hume, K., & Campbell, J. M. (2019). Peer interventions for students with autism spectrum disorder in school settings: Introduction to the special issue. School Psychology Review, 48(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2018-0081.V48-2

Hume, K., Sam, A., Mokrova, I., Reszka, S., & Boyd, B. A. (2019). Facilitating social interactions with peers in specialized early childhood settings for young children with ASD. School Psychology Review, 48(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0134.V48-2

Hume, K., Steinbrenner, J. R., Odom, S. L., Morin, K.L., Nowell, S. W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Ӧzkan, S. & Savage, M. N. (2021). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism: Third generation review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–20.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04844-2

Humphreys, A. P., & Smith, P. K. (1987). Rough and tumble, friendship, and dominance in schoolchildren: Evidence for continuity and change with age. Child Development, 58(1), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130302

Jensen, H., Pyle, A., Zosh, J. M., Ebrahim, H. B., Scherman, A. Z., Reunamo, J., & Hamre, B. K. (2019). Play facilitation: The science behind the art of engaging young children. The LEGO Foundation.

Jivraj, J., Sacrey, L. A., Newton, A., Nicholas, D., & Zwaigenbaum, L. (2014). Assessing the influence of researcher–partner involvement on the process and outcomes of participatory research in autism spectrum disorder and neurodevelopmental disorders: A scoping review. Autism, 18(7), 782–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314539858

Jordan, R. (2003). Social play and autistic spectrum disorders: a perspective on theory, implications and educational approaches. Autism, 7(4), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361303007004002

Jordan, R. (2019). Particular learning needs of individuals on the autism spectrum. In R. Jordan, J. M. Roberts, & K. Hume (Eds.), The sage handbook of autism and education (pp. 12–23). Sage.

Jung, S., & Sainato, D. M. (2013). Teaching play skills to young children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 38(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.732220

Juvonen, J. (2018). The potential of schools to facilitate and constrain peer relationships. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 491–509). The Guilford Press.

Kamps, D., Mason, R., Thiemann-Bourque, K., Feldmiller, S., Turcotte, A., & Miller, T. (2014). The use of peer networks to increase communicative acts of students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(4), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614539832

Kasari, C., & Smith, T. (2013). Interventions in schools for children with autism spectrum disorder: Methods and recommendations. Autism, 17(3), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312470496

Kasari, C., Freeman, S., & Paparella, T. (2006). Joint attention and symbolic play in young children with autism: A randomized controlled intervention study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(6), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01567.x

Kasari, C., Locke, J., Gulsrud, A., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2011). Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x