Abstract

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the efficacy of psychological therapies for anxiety for people with autism and co-occurring intellectual developmental disorder (AUT + IDD). A systematic search identified 13 studies comprising 49 participants with AUT + IDD, aged between 5 and 41 years. Most studies were single-case experimental designs (n = 7) or case studies or case series (n = 4). Studies implemented cognitive behavioural therapy (n = 4) or exposure therapy techniques (n = 9). All studies reported a reduction in anxiety symptoms, as measured by either quantitative measures or defined as participants meeting end of treatment criterion. However, the conclusions are preliminary due to the methodological limitations of the current literature. The implications of these findings, as well as recommendations for future direction in the field, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety is a common concern for autisticFootnote 1 individuals, including the 33 to 55 percent of autistic individuals with co-existing intellectual disability (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018; Charman et al., 2011; Rivard et al., 2015). While many anxiety interventions have demonstrated efficacy in the general population (e.g., see Bandelow et al., 2015; Sigurvinsdóttir et al., 2020), the characteristics of autism may render these interventions less effective in treating this population, particularly for individuals with co-occurring intellectual developmental disorder (intellectual disability) (IDD) (Fynn et al, 2022). With reviews available for autism and IDD alone (Fynn et al., 2022), this systematic review aimed to specifically evaluate studies investigating the efficacy of psychological interventions for anxiety in those with autism (AUT) and co-occurring IDD (AUT + IDD).

Autism is a pervasive and heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition characterised by two diagnostic hallmark features: (1) impaired social communication and interaction, and (2) restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). These features appear in early childhood and persist across the lifespan. These features occur on a spectrum with some individuals experiencing mild impairments, while others are more severely affected.

IDD is a developmental disability characterised by marked cognitive impairments, measured as performing greater than or equal to two standard deviations below the population mean on a standardised intelligence test, as well as significant difficulties with daily living skills, as measured by a clinical interview or standardised measure of adaptive functioning in the conceptual, social, and practical domains (APA, 2022).

Individuals with AUT + IDD require increased levels of support compared to individuals with IDD or AUT alone, as the impairments of one condition compound on the other (Matson & Shoemaker, 2009). For example, individuals with AUT + IDD have more severe social and communication impairments and increased restricted and repetitive behaviours than peers with IDD or AUT only (Matson & Shoemaker, 2009), which adversely affects their quality of life (Arias et al., 2018; Howlin & Magiati, 2017; Simões & Santos, 2016). In addition, individuals with AUT + IDD are at an increased risk of developing an anxiety disorder compared to the general population. One third of individuals with AUT + IDD have a co-occurring anxiety disorder (Bakken et al., 2010; Gobrial & Raghavan, 2012), which is greater than the global current prevalence rate in the general population (7.3%; Baxter et al., 2013) and in the IDD only population (5.4% and 3.8% in youth and adults respectively; Maiano et al., 2018; Reid et al., 2011). On the other hand, the prevalence rate in the AUT + IDD population is comparable to the prevalence rates in the AUT only populations (40%, Zaboski & Storch, 2018).

Anxiety in autistic and/or IDD Populations

Anxiety disorders are characterised by excessive worry or fear in response to a perceived threat or in anticipation of a future threat. The literature suggests that AUT and IDD may predispose individuals to anxiety due to: (1) the insistence on sameness and thus difficulties with change; (2) hypersensitivity to stimuli, which may explain anxieties like specific phobias of noise; (3) increased exposure to adverse psychosocial experiences (e.g., bullying, abuse, poor social support, underachievement); and (4) poor coping skills (Cooray and Bakala, 2005; Kerns et al., 2021; Mayes et al., 2013). Anxiety can be overlooked in individuals with AUT + IDD because symptoms of anxiety may be attributed autism or IDD, a phenomenon known as diagnostic overshadowing. For example, anxiety symptoms such as compulsive checking may be mistaken for a ‘need for sameness’, and social avoidance may be attributed to social communication impairments in autistic individuals or a lack of interest in social interactions (Kerns et al., 2015). Further, anxiety disorders may also go unnoticed due to differences in presentation compared to the general population. Kerns et al. (2014) estimated that 46% of autistic children showed atypical anxiety symptoms, such as sensory-related fears and compulsive rigidity, that were inconsistent with criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (5th ed.; APA, 2013). Finally, the measures used for screening were developed and validated for the general population, and so are less sensitive to the anxiety symptoms experienced by individuals with autism and/or IDD. As many individuals with AUT and/or IDD have significant expressive communication impairments, their parents and caregivers rely on behavioural signs to identify anxiety. Despite this, measures of anxiety symptomatology often focus on internal mental states and thoughts rather than behaviours. Fortunately, a growing body of literature seeks to overcome this issue by investigating typical and atypical symptoms of anxiety in ASD (Wood & Gadow, 2010), and developing sensitive measures of anxiety that consider autistic characteristics (Rodgers et al., 2016; Scahill et al., 2019; Toscano et al., 2020).

Kerns et al. (2015) highlight the importance of diagnosing and treating co-occurring anxiety in the autistic population. Results revealed significantly greater self-injurious behaviour, depressive symptoms, and parental stress in autistic individuals with a co-occurring anxiety diagnosis compared to those without an anxiety diagnosis (Kerns et al., 2015). Other consequences of anxiety may include school refusal, difficulties accessing medical and dental care, and reduced independence as parents and caregivers take over tasks that are anxiety provoking. Overall, the literature suggests that anxiety is associated with reduced quality of life in autistic individuals (Adams et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2019; van Steensel et al., 2012). This is also likely to be true for the AUT + IDD population, although research in this specific population is lacking. Nevertheless, there is a clear need for effective treatment.

While many anxiety interventions have been developed and have demonstrated efficacy in the general population (Goncalves & Byrne, 2012; Velting et al., 2004), and, to a lesser degree, the IDD population (see Fynn et al., 2022 for a recent review) and the AUT population (Kester & Lucyshyn, 2018; White et al., 2018), the characteristics of AUT + IDD may render these interventions less effective in treating these populations. For example, some autistic individuals present with uncommon phobias (e.g., fears of loud noises, mechanical objects, and toilets) and/or atypical coping strategies (e.g., repetitive self-injurious behaviours, withdrawal, and externalising behaviours; Halim et al., 2018; Kerns et al., 2014), which may not be adequately addressed with standard interventions. Intervention is also complicated by the differences in cognitive and language abilities amongst individuals with autism and/or IDD, which necessitates a flexible and patient-centred approach to treatment. Therefore, it is important to investigate the ways in which previous studies have treated anxiety in the AUT + IDD population, and to evaluate the efficacy of these interventions, so that future modifications can be made in an evidence-based manner, which increases the likelihood of positive outcomes.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to Treat Anxiety

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the gold-standard psychological therapy within the general population for the treatment of anxiety (David et al., 2018). CBT targets the symptoms of anxiety with a combination of cognitive (e.g., identifying emotions and anxious thoughts, and challenging maladaptive thoughts and cognitive distortions) and behavioural techniques (e.g., graduated exposure or systematic desensitisation). However, there has been debate in the literature regarding the suitability of CBT for AUT (Lickel et al., 2012) and IDD (Fynn et al., 2022; Hronis et al., 2017) populations, particularly as cognitive strategies of CBT rely heavily on meta-cognitive abilities that may be impaired in both these populations, as well as general cognitive abilities such as expressive and receptive language, abstract thinking, and memory. For example, language and meta-cognitive skills are required for understanding and communicating anxious feelings and thoughts; abstract reasoning and cognitive flexibility are needed when engaging in hypothetical scenarios; memory is used to learn and implement coping strategies and metacognition is used to challenge maladaptive thoughts (Rosen et al., 2016; Rotheram-Fuller & MacMullen, 2011). Hence, researchers have proposed several modifications to better tailor CBT to AUT and/or IDD populations. These modifications (similar across AUT and ID) include delivering the intervention one-on-one rather than a group format, increasing parental involvement, focusing on physical symptoms rather than emotional symptoms when identifying anxiety, short sessions, and incorporating visual aids, stories, social skills training, and role-playing into the program (Hronis et al., 2017; Moree & Davis, 2010; Rotheram-Fuller & MacMullen, 2011).

Previous Reviews on the Treatment of Anxiety in autistic and/or IDD Populations

Systematic reviews and meta-analysis have evaluated the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety in IDD and/or autistic populations. Two systematic reviews focused on the IDD population; Dagnan et al. (2018) evaluated 19 studies and all but one reported a positive outcome, while Fynn et al. (2022) found decreases in participants’ anxiety in seven of nine included studies with mixed results in the other three studies. Overall, Fynn et al. reported that effect sizes (r) ranged from minimal (0.20), to strong (0.80) and the effect sizes for ωp2 ranged from minimal (0.04), to strong (0.64) in the nine studies reviewed.

In the autistic population, at least nine systematic reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated CBT as a treatment for anxiety (Kester & Lucyshyn, 2018; Kreslins et al., 2015; Lang et al., 2010; Perihan et al., 2020; Spain et al., 2018; Sukhodolsky et al., 2013; Ung et al., 2015; Vasa et al., 2014; Weston et al., 2016). Most of the reviews conclude that CBT is, at the very least, a promising treatment (Kreslins et al., 2015; Perihan et al., 2020; Spain et al., 2018; Vasa et al., 2014;). Other reviews have greater confidence in CBT; Ung et al. (2015) claim CBT to be “robustly efficacious”, and Kester and Lucyshyn (2018) classify CBT as an ‘empirically supported treatment’ for AUT using the Council for Exceptional Children criteria. Overall, these previous meta-analyses in the AUT population have found small, yet still notable, effect sizes (g = -0.56 and -0.47; Perihan et al., 2020; Ung et al., 2015) compared to those found in the general population (e.g., g = 0.69; Watts et al., 2015).

Other psychological therapies have also been systematically reviewed in the autistic population and have demonstrated positive outcomes, including mindfulness (Cachia et al., 2016) and acceptance and commitment therapy (Byrne and O’Mahony, 2020). Social skills therapy and social recreation programs have also been suggested to decrease social anxiety in autistic children (Delli et al., 2018) . In the IDD population, a meta-analysis of psychological therapies for children and adults with IDD found, overall, a moderate effect size (g = 0.56) across 23 studies, but the review covered other psychological conditions aside from anxiety, including depression and anger management, and when CBT was excluded, there was reportedly insufficient evidence regarding the efficacy of other psychological therapies for ID, such as role play and parental psychoeducation (Vereenooghe & Langdon, 2013). Prout and Nowak-Drabik (2003) reported a moderate treatment effect across 92 studies from 1968 to 1998 for social skills training, assertiveness training, relaxation, and other psychological therapies for those with ID, but the nature of the condition being treated was not well-specified and appeared not to cover mental health diagnoses or symptomology, per se, but rather “feelings, values, attitudes and behaviours” (p. 84).

While the aforementioned reviews have demonstrated the potential of psychological therapies, particularly CBT, in reducing anxiety in the AUT and IDD populations, the majority have either included studies with samples of AUT individuals without an IDD diagnosis (Kester & Lucyshyn, 2018; Kreslins et al., 2015; Perihan et al., 2020; Sukhodolsky et al., 2013; Ung et al., 2015; Vasa et al., 2014), or did not report information relating to intellectual functioning (Lang et al., 2010; Spain et al., 2018; Weston et al., 2016). Hence, the findings cannot be generalised to individuals with AUT + IDD.

To the authors’ knowledge, only two reviews have evaluated therapy for anxiety in individuals with “low-functioning” autism (Rosen et al., 2016; Winch et al., 2022). Rosen et al. (2016) reviewed behavioural therapies and found desensitisation and reinforcement techniques to be efficacious in the “low-functioning” autistic population. However, the authors defined “low functioning” based on impaired verbal, adaptive, intellectual, and/or developmental abilities, rather than a diagnosis of IDD. Winch et al. (2022) reviewed the literature, and described the assessment, as well as treatment, of anxiety in individuals with AUT + IDD. The authors concluded that CBT may be effective, particularly when modifications are implemented to make the intervention more accessible to this population. However, Winch et al.’s (2022) review was limited, as it did not employ systematic review methodology.

The Current Review

Considering the prevalence and effects of anxiety in the AUT + IDD population, the need for efficacious anxiety treatment is required. However, treatment of anxiety is hindered by the lack of understanding of evidence-based interventions in this group, and limited research on this topic to date. To the authors’ knowledge, no systematic reviews have investigated the efficacy of psychological therapy for anxiety in the AUT + IDD population. Hence, this systematic review aimed to investigate which psychological therapies are most effective for treating anxiety in autistic individuals with IDD. This review also discusses the modifications made to the psychological therapies that are best suited to the AUT + IDD population. These findings identified current limitations and gaps in the literature to guide future research, and described the characteristics and techniques of effective psychological therapies, which can shape future interventions and can be used to inform clinical practice guidelines for anxiety treatment in the AUT + IDD population.

Methods

Protocol Registration

In accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, this research methodology was published on PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO) prior to data collection (registration number: CRD42021237960).

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies were required to meet all the following criteria: (1) participants have a diagnosis of ASD (or previous diagnostic equivalent, e.g., autistic disorder or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified); (2) participants have a diagnosis of IDD (or previous diagnostic equivalent, or developmental delay in younger individuals); (3) participants engaged in psychological therapy to treat anxiety symptoms; (4) at least one outcome measure of anxiety; and (5) the study reports original empirical data. Psychological therapy was defined as an intervention “in which the therapist and patient(s) work together to ameliorate psychopathologic conditions and functional impairment through focus on the therapeutic relationship; the patient’s attitudes, thoughts, affect, and behaviours; and social context and development” (Brent & Kolko, 1998, p. 17). An outcome measure was defined as any tool (standardised or unstandardised) or prespecified treatment endpoint or goal(s) related to the treatment of anxiety.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) the effects of the psychological therapy could not be isolated from other treatments (e.g., pharmacotherapies), and (2) the effects on participants with AUT + IDD could not be isolated from other participant groups (e.g., other neurodevelopmental disorders or neurological conditions). No restrictions on participant age, study design, or publication date were imposed. Only peer-reviewed publications were included.

Information Sources

Electronic database searches were performed on the 20 August 2021 on six databases: PsycINFO [1806 – August Week 2], SCOPUS, EMBASE [1974 – August 19], Medline [1946 – August 19], CINAHL, and the Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection. This was supplemented by checking the reference lists of eligible studies.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was as follows: (autis* OR ASD OR pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified OR PDD-NOS) AND (((learn* or intellect*) adj2 (disorder* or impair* or disab* or dysfunction*)) OR mental retardation OR mental* handicap*) AND (anxiet* OR phobi* OR panic disorder OR agoraphobia OR mutism OR generali* anx* disorder OR GAD OR ((overanxi* OR avoidan* OR internali*) adj2 disorder*)) AND (interven* OR therap* OR psychotherap* OR treatment). The search strategy was adapted, as necessary, to suit the operators and commands of each database.

Study Selection

The first author and a research assistant [CK and QZ] independently screened, examined, and selected the studies included in the review. Search results were imported into EndNote to remove duplicates. Then, the remaining search results were imported into Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai). Screening of the search results occurred in two stages: first by title and abstract and then full text. The two screeners were blinded to each other’s decisions. Inter-rater agreement was 99.6%. The disagreements were settled by the third author [MP].

Data Extraction and Study Quality Assessment

Once the studies were identified, the first author extracted the data [CK]. Information extracted included: study design, sample size, age statistics, intelligence quotients and adaptive behaviour composite scores and/or IDD severity, type of psychological therapy intervention, mode of intervention delivery, duration of intervention, outcome measure(s), and results.

The first author and a research assistant [CK and MB] independently appraised the quality of the included studies. The single case experimental studies (n = 7) were assessed using the Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) scale (Tate et al., 2013). The RoBiNT scale is comprised of 15 items with each item rated on a 3-point scale (0, 1, or 2). There are two subscales: the internal validity subscale and the external validity and interpretation subscale. Methodological rigour was evaluated using Perdices et al.’s (2019) algorithm, which is based on the internal validity subscale; classifications include Very High, High, Moderate, Fair, Low, and Very Low. There are no established cut-off points or classifications for the external validity subscale.

The remaining studies were appraised using the National Institutes of Health quality assessment tools. These tools allow a comprehensive review of several study designs, including before-and-after studies and case studies. The before-and-after studies assessment tool is comprised of 12 items, and the case studies assessment tool is comprised of nine items. Each item was rated with either ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Not Reported’, or ‘Not Applicable’. These studies were given an overall rating based on the percentage of ‘Yes’ responses. This was calculated by dividing the number of ‘Yes’ responses with the number of items on the assessment tool minus the number of ‘Not Applicable’ responses. Ratings were ‘good’ (≥ 75%), ‘fair’ (50 – 74%), and ‘poor’ (< 50%). This rating system is similar to that used by Camm et al. (2021).

Inter-rater agreement for the studies’ ratings across all the items on the RoBiNT and NIH scales was 92.12%. Disagreements were settled through discussion with a third person [MP].

Results

Study Selection

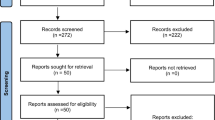

The search of the databases yielded 3,094 results, 1,351 of which were duplicates. Books and book chapters were removed (n = 239). 1,504 records were screened based on title and abstract, 1,464 of which were excluded. 43 full-text papers were assessed. A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. A PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Study Characteristics

The main characteristics of the included studies, such as the study design, sample size, participant details (e.g., ages, IQ/IDD severity, type of anxiety), intervention, measures of anxiety, and treatment outcomes, are presented in Table 1.

Study Design

Seven of the thirteen included studies were single-case experimental designs, including two concurrent multiple baseline designs (Fodstad et al., 2021; Luscre & Center, 1996), one nonconcurrent multiple baseline design (Moskowitz et al., 2017), three changing criterion designs (Chok et al., 2010; Meindl et al., 2019; Wolff & Symons, 2012), and one ABAB reversal design (Shabani & Fisher, 2006). Four of the thirteen included studies were single-case studies or case series (Burton et al., 2017; Muskett et al., 2020; Poornima et al., 2019; Wright, 2013). The remaining two studies by Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) and Gobrial and Raghavan (2018) were single-group pre-post studies with samples sizes of 23 and 7 participants, respectively.

There was variation in the primary outcome measures used. Most studies utilised observational outcome measures, such as the number of successful exposure trials or the frequency of anxious behaviours (Burton et al., 2017; Chok et al., 2010; Fodstad et al., 2021; Luscre & Center, 1996; Meindl et al., 2019; Moskowitz et al., 2017; Poornima et al., 2019; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012). Four studies administered standardised measures to quantify the severity of anxiety symptomatology pre- and post-intervention (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Gobrial and Raghavan, 2018; Muskett et al., 2020; Wright, 2013) . Anxiety measures included: the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule–Parent Version—5th Edition (ADIS-P-5; Albano & Silverman, 1996); the Anxiety Depression and Mood Scale (ADAMS; Esbensen et al., 2003); the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI, Derogatis, 1975); the Fear Survey Schedule for Children-Revised (FSSC-R; Ollendick, 1983); the Glasgow Anxiety Scale for Children with Intellectual Disabilities (GAS-ID; Mindham & Espie, 2003); and the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders – Parent version (SCARED-P; Birmaher et al., 1999).

Five of the thirteen studies included a follow-up phase, ranging from 2 weeks to 6 months post-intervention (Chok et al., 2010; Meindl et al., 2019; Muskett et al., 2020; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012). These five studies delivered exposure-based interventions, so the follow up phases typically conducted exposure trials similar to that given during the intervention. Muskett et al. (2020) was the exception; a ‘hypothetical’ exposure trial was conducted as the participant lived remote from the clinic. The hypothetical exposure trial was supplemented by re-administering the ADIS-P-5.

Participants

A total of 49 individuals (40 males) with AUT + IDD participated in psychological therapy for anxiety across the included studies. Participants were aged between 5 and 41 years, with most studies (n = 11) recruiting children and adolescents. In terms of ASD diagnosis, Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) reported that the participants’ diagnosis was determined by the results of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – 2nd edition, while Muskett et al. (2020) corroborated ASD diagnosis using symptomology questionnaires: the Social Communication Questionnaire (Rutter, et al., 2003), Short Sensory Profile (Dunn, 1999), and Repetitive Behaviour Scale – Revised (Lam & Aman, 2007). The remaining studies did not provide additional information on the participants’ ASD diagnoses.

There was significant variation in the severity of the participants’ IDD and the reporting of this information. Three studies reported IQ and/or adaptive behaviour composite scores, with scores across the studies varying from mild to severe IDD (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Burton et al., 2017; Moskowitz et al., 2017). Luscre and Center (1996, p. 549) reported the mental and adaptive ages of their participants: the participants were functioning at the “severely mentally retarded level”. Of the studies that did not report standardised test scores, one case study discussed a participant with “mild” IDD (Fodstad et al., 2021), two case studies discussed participants with “moderate” IDD (Chok et al., 2010; Meindl et al., 2019), and one group study recruited participants with “mild to moderate” IDD, but did not state the number of participants in each severity level (Gobrial & Raghavan, 2018). Five studies stated that their participants had IDD but did not indicate the severity level (Muskett et al., 2020; Poornima et al., 2019; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012; Wright, 2013).

Regarding the anxiety disorder diagnosis, two studies stated that their participants met DSM criteria (4th ed., text rev., 5th ed.; APA, 2000, 2013) for a specific phobia (Chok et al., 2010; Muskett et al., 2020), and another study stated that their participants met DSM criteria (4th ed.; APA, 1994) for an anxiety disorder but did not specify which anxiety type (Moskowitz et al., 2017). As part of their inclusion criteria, Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) required participants to have clinically significant levels of anxiety on the ADAMS (Esbensen et al., 2003) and SCARED-P (Birmaher et al., 1999). Fodstad et al. (2021) treated participants with noise hypersensitivity, which was conceptualised as a specific phobia; this was corroborated with clinically significant scores on the ADIS-P-5 (Albano & Silverman, 1996). Wright (2013, p. 285) stated that their participant “was assessed by a psychiatrist to be experiencing generalised social phobia in the context of ASD”. Gobrial and Raghavan (2018) stated that the participants recruited for phase one of their study (i.e., exploration of intervention strategies with parents and teachers) had to meet the International Classification of Diseases criteria (10th ed.; World Health Organization, 2016) for an anxiety disorder. However, it was unclear whether this criterion was also used for participants for phase two (i.e., implementation and evaluation of the intervention). The remaining six studies did not mention whether the participants were diagnosed or assessed for an anxiety disorder, although these participants were described to exhibit specific phobia symptomatology (Burton et al., 2017; Luscre & Center, 1996; Meindl et al., 2019; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012) or separation anxiety (Poornima et al., 2019).

Overall, most studies targeted specific phobia or specific phobia-like symptoms for dogs (Burton et al., 2017; Chok et al., 2010; Muskett et al, 2020), needles/blood draw (Meindl et al., 2019; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012), noise (Fodstad et al., 2021), dentists (Luscre & Center, 1996) or other idiosyncratic fears (Moskowitz et al., 2017). Social anxiety and other non-specified anxieties were also targeted (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Gobrial & Raghavan, 2018; Wright, 2013).

Most studies did not report whether participants were taking any concurrent psychotropic medications (Burton et al., 2017; Chok et al., 2010; Fodstad et al., 2021; Luscre & Center, 1996; Meindl et al., 2019; Muskett et al., 2020; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wright, 2013). Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) reported that 61.9% of their participants were on medication for anxiety, and the inclusion criteria required the dose to be stable over the duration of the study (i.e., one month prior to intervention and two months after). Gobrial and Raghavan’s (2018) exclusion criteria included other interventions for anxiety, including medication. Moskowitz et al. (2017) reported that none of their participants were taking any medication. Poornima et al. (2019) reported that their participant received pharmacological treatment in addition to psychological therapy. Wolff and Symons (2012) reported that their participant’s phobia prevented him from receiving medical treatment, including blood draws, even with anxiolytic medication. The reporting of the case study suggests that the participant was not taking anxiolytics during the intervention (Wolff & Symons, 2012).

Interventions

Studies included in this review investigated either CBT or exposure-based interventions. Although exposure is central to CBT, exposure in the absence of cognitive strategies cannot be considered CBT. Hence, the interventions are grouped in this way throughout this review.

Nine studies implemented interventions based on exposure strategies, such as systematic desensitisation, reinforced practice, stimulus fading, and differential reinforcement (Burton et al., 2017; Chok et al., 2010; Fodstad et al., 2021; Luscre & Center, 1996; Meindl et al., 2019; Muskett et al., 2020; Poornima et al., 2019; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012). These eight studies tailored the intervention to each individual participant and delivered the intervention one-on-one. Notably, Meindl et al. (2019) had a novel delivery approach by utilising virtual reality for exposure trials.

Four studies implemented interventions that were based on CBT principles (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Gobrial & Raghavan, 2018; Moskowitz et al., 2017; Wright, 2013). Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) delivered a modified version of the established group program, ‘Facing Your Fears’. Wright (2013) delivered CBT in an individualised program formulated by the researching clinician. Moskowitz et al. (2017) utilised a combination of CBT and positive behaviour support strategies (e.g., increasing predictability, providing choices, generalised reinforcement, differential reinforcement of alternative behaviour, and escape extinction) to treat their participants. Finally, Gobrial and Raghavan (2018) developed and implemented a parent-delivered program, in which parents were sent an information pack that provided psychoeducation on anxiety disorders in children with AUT + IDD and detailed strategies for managing anxiety. The CBT components utilised in the studies’ interventions are presented in Table 2.

The frequency and intensity of the CBT interventions varied. Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) delivered 14 weekly sessions with each session running for 45 to 60 min, Gobrial and Raghavan (2018) evaluated the parent-implemented program over a three-month period, Moskowitz et al. (2017) delivered between 4–10 weeks of intervention, and Wright (2013) delivered 11 weekly 60-min sessions.

Intervention Modifications to Support the AUT + IDD Population

Burton et al. (2017) and Muskett et al. (2020) argued that the cognitive components of CBT relied heavily on verbal abilities. Hence, their interventions were comprised solely on behavioural strategies. In contrast, Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) made several adaptions to CBT to accommodate participants of differing language levels. For example, emotion regulation content could be provided using pictorial-based instruction or using verbal and written instruction, and participants were taught to identify and communicate their emotions either by using a simplified scale (‘green, yellow, or red’) or by using emotive words.

Other modifications included: the use of visual scheduling (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Burton et al., 2017; Moskowitz et al., 2017); visual menus (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Fodstad et al., 2021); video modelling (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Moskowitz et al., 2017); social stories (Moskowitz et al., 2017) and alternative or augmentative communication methods (Burton et al., 2017). The child’s specific interests were also included (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Moskowitz et al., 2017), there was increased parent involvement (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Muskett et al., 2020), content was often repeated (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021) and content was activity-based to reduce didactic instruction (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021). The frequency and duration of the interventions were also amended so that session lengths were shorter (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021), group sizes were reduced (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021), and more sessions were delivered (Muskett et al., 2020). Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) also added some content to the parent curriculum of the ‘Facing Your Fears’ CBT program, so that parents learnt to identify the physical symptoms of anxiety and fears, and the importance of supporting the child’s independent use of strategies in addition to the original content.

Methodological Quality

A summary of the quality appraisal ratings for each study are found in the Supplementary Material. Amongst the single-case experimental designs, three studies were classified as having ‘moderate’ methodological rigour (Chok et al., 2010; Meindl et al., 2019; Shabani & Fisher, 2006), one study as ‘fair’ (Wolff and Symons, 2012), two as ‘low’ (Fodstad et al., 2021; Luscre & Center, 1996), and one as ‘very low’ (Moskowitz et al., 2017) . All the studies had at least reasonable interrater agreement, and clear descriptions of the participants’ baseline characteristics, setting, intervention, and the outcome measures. However, many studies did not randomise the phase sequence or phase commencement (n = 6), utilise blind assessor(s) (n = 6), measure or have adequate treatment adherence (n = 6), include systematic or intra-subject replication (n = 5), or adequately generalise the findings (n = 6).

Amongst the case studies, one study was classified as ‘good’ (Muskett et al., 2020), one study as ‘fair’ (Wright, 2013), and two studies ‘poor’ (Burton et al., 2017; Poornima et al., 2019). Methodological strengths clearly described interventions (n = 3) and results (n = 3). Some studies were also rated as utilising prespecified, clearly defined, valid and reliable outcome measures (n = 3). However, the authors note that none of the anxiety measures utilised have been validated in the AUT + IDD population. Outcomes measures were rated as valid if they were validated in the IDD or autistic populations.

Common problems included a lack of adequate follow-up (n = 3), unclear study questions or objectives (n = 2). Two studies also provided unclear descriptions of the study population. More specifically, studies often stated that their participants were diagnosed with autism and IDD, but did not report on how these diagnoses were made, the severity of the IDD diagnosis was occasionally unclear, and/or there was also a lack of information regarding participants’ medications and previously attempted interventions for their anxiety.

Both pre-post studies were rated as ‘fair’ (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021; Gobrial & Raghavan, 2018). Both studies clearly: stated the study question or objective; pre-specified and clearly described their eligibility criteria; had samples that were representative of clinical population of interest; utilised prespecified, clearly defined, valid and reliable outcome measures; and utilised statistical methods that examined changes in the outcome measures. However, both studies did not have sufficiently large sample sizes to provide confidence in their findings, did not blind the outcome raters to the participants’ interventions, and did not utilise an interrupted time-series design.

In addition to the items on the RoBiNT scale and National Institutes of Health quality rating scales, there was poor ascertainment of autism and IDD diagnoses and a lack of reporting on participant engagement in the interventions.

Results of the Included Studies

The included studies investigated either CBT or exposure-based therapy. Hence, the results have been grouped by therapy so that the efficacy of the therapies can be compared.

CBT-based Interventions

Blakeley-Smith et al.’s (2021) pilot study assessed the efficacy of a manualised group program, Facing Your Fears, which was modified for adolescents with AUT + IDD. The authors reported statistically significant reductions across several parent-reported anxiety measures including all subscales of the ADAMS: total (ω2p = 0.45), obsessive–compulsive (ω2p = 0.18), general anxiety (ω2p = 0.25), social avoidance (ω2p = 0.50), depressed mood (ω2p = 0.23), and manic/hyper (ω2p = 0.20), on the total and separation subscale of the SCARED-P (ω2p = 0.14 and ω2p = 0.18, respectively), and on the total FSSC-R score (ω2p = 0.20). These effect sizes were all large in magnitude. Similarly, Gobrial and Raghavan (2018) reported a statistically significant decrease in parent-reported GAS-ID scores (Z = -2.371, p < 0.05), with 85% of participants falling below the cut-off point of clinically significant anxiety after 3-months of the parent-implemented Calm Child Program. Moskowitz et al. (2017) evaluated an intervention based on CBT and Positive Behaviour Support strategies and found a reduction in anxiety quantified using behavioural observations (anxiety rated by blinded undergraduate research assistants, and frequency of anxious behaviours observed by study authors) and physiological measures (heart rate and respiratory sinus arrhythmia). Wright (2013) delivered an individualised program of CBT and reported a decrease on an unstandardised measure of self-rated anxiety (U = 66, z = -4.42, p = 0.000). Wright (2013) also depicted a decrease in the raw BSI anxiety score of approximately 2 points on a figure. However, the clinical significance of these scores was unclear as the corresponding standardised scores were not reported. No follow-up phases were completed by any of the CBT-based intervention studies.

Exposure-based Interventions

Burton et al. (2017), Chok et al. (2010), Fodstad et al. (2021), Luscre and Center (1996), Meindl et al. (2019), Shabani and Fisher (2006), and Wolff and Symons (2012) reported on successful treatment of specific phobias, as measured by completion of the pre-determined exposure hierarchy steps, or meeting end of treatment criterion or clinically significant criterion. Heart rate was also used as an additional measure by Chok et al. (2010) and Fodstad et al. (2021), and the results were in support of treatment success. That is, heart rate was found to decrease across trials (Fodstad et al., 2021) or remain within the participants baseline zone (Chok et al., 2010). Poornima et al. (2019) reported a decrease in the number of challenging behaviours per day and an increase in the tolerated time separated from the participant’s mother. Muskett et al. (2020) was the only exposure-based intervention study to utilise a standardised anxiety measure. Results demonstrated a clinically significant and reliable decrease in the participant’s ADIS-P-5 Clinical Severity Rating (Reliable Change Index = -3.03).

As previously mentioned, several studies included a follow up phase, ranging from 2 weeks to 6 months post-intervention (Chok et al., 2010; Meindl et al., 2019; Muskett et al., 2020; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012). All studies reported maintenance of treatment gains.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this was the first systematic review of its kind to investigate the efficacy of psychological therapy for anxiety in the AUT + IDD population. The systematic search identified 13 eligible studies, comprising of 49 participants with AUT + IDD who underwent either CBT or an exposure-based therapy to treat anxiety. Included studies typically employed single-case designs, selected children and adolescents as participants, and targeted specific phobias. Due to the preliminary nature of the studies and the variability amongst them, it is difficult to compare and generalise results. Methodological quality was variable ranging from ‘moderate’ to ‘very low’ using the RoBiNT scale and ‘good’ to ‘poor’ using the National Institutes of Health quality assessment tools. Hence, results must be interpreted with consideration of the studies’ methodological challenges, including a lack of measures validated for the AUT + IDD population, inadequate follow up, and small sample sizes. Nevertheless, the findings are, to some degree, optimistic and highlight avenues for future research. All studies reported a reduction in anxiety following intervention, as measured by either quantitative measures or defined as participants meeting end of treatment criterion. These findings are congruent to those previously reported in the literature. Lydon et al.’s (2015) review also found positive outcomes for treating fears and phobias in autistic individuals with behavioural techniques, while Jennett and Hagopian (2008) found similar outcomes for treating phobic avoidance in individuals with IDD. Cognitive behavioural therapy, including the individual elements such as psychoeducation, cognitive challenges, and exposure techniques, was also found to be generally effective, but lacking sufficient evidence (Lydon et al., 2015). Similarly, Rosen et al.’s (2016) review also concluded that behavioural interventions reduce anxiety-related difficulties in “low functioning” autistic individuals. Hence, the current literature lends tentative support for treating anxiety with exposure therapies and CBT in the AUT + IDD population.

Psychological Therapies for Anxiety in the AUT + IDD Population

In this systematic review, studies investigating exposure-based therapies alone outnumbered those investigating CBT. This likely reflects the prevalence of specific phobias in the AUT + IDD population, as exposure therapy is considered the most effective treatment for specific phobia in the general population (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). Indeed, this review has also demonstrated that exposure therapy is effective is treating specific phobias in the AUT + IDD population. Furthermore, when a follow-up session was conducted, these treatment outcomes were shown to be maintained over time (Chok et al., 2010; Meindl et al., 2019; Muskett et al., 2020; Shabani & Fisher, 2006; Wolff & Symons, 2012).

Nevertheless, there is emerging interest in utilising CBT in the AUT + IDD population. Although the use of cognitive interventions in individuals with cognitive deficits has not been viewed favourably, the current systematic review provides some grounds for questioning this notion. Findings show that CBT reduces anxiety in the AUT + IDD population, particularly when modifications are made to support the participants’ cognitive impairments. Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) successfully modified the Facing Your Fears program by using pictorial- and activity-based instruction, increasing parent involvement, shortening sessions, and reducing group sizes. It is important to note that such modifications are not limited to CBT programs, but can be applied, where appropriate, to any intervention or activity (e.g., schoolwork) to increase the engagement of individuals with autism and/or IDD. Other modifications implemented in the included studies were visual scheduling, visual menus, modelling, social stories, alternative or augmentative communication methods, the inclusion of the child’s specific interests, and repetition of content. These findings demonstrate several strategies for overcoming the challenges that arise when treating the AUT + IDD population and expands the scope for targeting non-phobia anxiety types such as generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety.

At this time, no conclusions can be drawn as to which therapy—CBT or exposure therapy—is most effective. First, studies have utilised exposure therapies for specific phobias, while CBT has been used for social anxiety, idiosyncratic fears, and unspecified anxiety. As the anxiety subtypes vary in their manifestations, it is likely that different interventions will work best for each subtype. Hence, comparisons cannot be made until different interventions are trialled for single anxiety subtypes. Secondly, while CBT has been demonstrated to be effective, it is uncertain as to which component—that is, the cognitive or behavioural techniques—is responsible for reducing anxiety. Future studies should conduct component analyses to address this gap in the literature.

The efficacy of therapies is not only influenced by the type of intervention, but also the mode of delivery. For individuals with complex needs, including those with AUT + IDD, individualised programs are popular due to the ease with which they can be modified. In contrast, group interventions are seldom used for AUT + IDD individuals. Of the thirteen studies in this review, only one study delivered an anxiety intervention in a group setting (Blakeley-Smith et al., 2021). Encouragingly, the results demonstrated that participants had significant reductions in anxiety after engaging in the group CBT program as measured by several parent-reported anxiety questionnaires. This suggests that individual and group administration of CBT may be similarly efficacious; however, this requires greater exploration using more rigorous study methodology. If this finding is replicated, this would have wide clinical implications as group interventions are generally more cost- and resource-effective, which can increase treatment access.

Quality of the Literature

The current evidence base is limited by a preponderance of case studies and the associated methodological flaws of this design. For example, small samples, a lack of control groups, and a lack of randomisation and blinding. Inadequate follow up was also noted. Aside from these limitations, the included studies did not adequately ascertain the diagnoses of their participants. In future, authors should establish ASD diagnosis using gold-standard assessment measures like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd edition (Lord et al., 2012). Alternatively, authors can ascertain diagnosis by sighting assessment reports written by a qualified clinician as a minimum. Authors should describe the method of ascertainment in their publications.

Similarly, researchers should also aim to establish IDD diagnosis using a standardised assessment of intelligence and adaptive behaviour. However, intelligence assessments may not be feasible in some individuals with ASD + IDD. In these circumstances, the individual’s language and adaptive abilities should be estimated to inform modifications for the cognitive and language-heavy components of the anxiety intervention.

Another limitation is the lack of validated anxiety measures for the AUT + IDD population (see Winch et al., 2022 for review); however, this is a wider issue rather than an oversight by the authors of the current literature. This lack of validated anxiety measures may account for the dependence on behavioural observations and number of successful exposure trials when determining the outcome of treatment in many of the included studies. For the few studies that utilised standardised anxiety questionnaires, the authors often made efforts to find a suitable measure from those available. For example, Blakeley-Smith et al. (2021) utilised the ADAMS, a questionnaire developed for individuals with IDD, and the SACRED-P, which has been demonstrated to have good sensitivity and specificity in autistic children (Stern et al., 2014), and Gobrial and Raghavan (2018) utilised the Glasgow Anxiety Scale for People with an Intellectual Disability.

It should also be noted that questionnaire measures used in the current literature are typically parent-report. Only one study (Wright, 2013) included a measure of self-rated anxiety, albeit unstandardised, to supplement the parent-report measure. Clinicians should be cautious when interpreting results that are based on a single informant. Previous reviews on psychological therapy for anxiety in the autistic population have noted differences in treatment effect size across informants. Kreslins et al. (2015) and Weston et al. (2016) found significant medium effects sizes when anxiety was measured using parent or clinician reports, while self-report measures of anxiety failed to reach statistical significance. This difference may reflect the challenges of utilising self-report anxiety measures in the autistic population; that is, impaired affect recognition, poor insight, difficulties conceptualising and verbalising their worry, and language difficulties hindering comprehension of the measure’s items (Toscano et al., 2020) . However, Weston et al. (2016) suggest that anxiety reductions reported by clinicians and parents may be due to an observer-expectancy effect. To address this, future studies should incorporate reports from multiple informants, in addition to objective physiological measures such as heart rate. Blinded assessors can also reduce bias.

Limitations of the Current Review

As previously mentioned, the variation in study designs, type and delivery of psychological therapy, and outcome measures precluded direct comparison of the studies’ results. However, rather than restricting the eligible studies based on methodology or study design, the authors agreed that a review of all available studies would be most suitable given the paucity of studies that investigate the efficacy of psychological therapy for anxiety in the AUT + IDD population. In addition, there is a possible reporting bias, as the current search did not include grey literature. Finally, included papers were limited to those published in English. Hence, the preliminary conclusions made in this review are limited in their generalisability.

This systematic review sought to summarise and evaluate the current research in psychological therapies for anxiety for autistic individuals with IDD. Overall, exposure therapy and CBT are somewhat promising, yet relatively untrialled, treatments for anxiety in the AUT + IDD population. There remains a need for more extensive research and replication across a wider range of anxiety types, interventions, and delivery styles. Nonetheless, considering the heterogeneity amongst this population, no one intervention is likely best for all individuals with AUT + IDD. Rather, a case-by-case approach is most appropriate; clinicians should make decisions that best support their patients’ interest by considering the nature of the patient’s anxiety, their cognitive and developmental level, and their treatment preferences and goals.

Notes

Identity-first language and the term ‘autism’ (rather than ‘autism spectrum disorder’) was used because it is preferred by the autistic community (Kenny et al., 2016). However, when referring to the diagnosis, appropriate nomenclature was used as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.; APA, 2022).

References

Adams, D., Clark, M., & Keen, D. (2019). Using self-report to explore the relationship between anxiety and quality of life in children on the autism spectrum. Autism Research, 12(10), 1505–1515. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2155

Albano, A. M., & Silverman, W. K. (1996). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV—Child Version: Clinician manual. Psychological Corp

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.)

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.).

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Arias, V. B., Gómez, L. E., Morán, M., Alcedo, M., Monsalve, A., & Fontanil, Y. (2018). Does quality of life differ for children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability compared to peers without autism? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3289-8

Bakken, T. L., Helverschou, S. B., Eilertsen, D. E., Heggelund, T., Myrbakk, E., & Martinsen, H. (2010). Psychiatric disorders in adolescents and adults with autism and intellectual disability: A representative study in one county in Norway. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(6), 1669–1677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.04.009

Bandelow, B., Reitt, M., Röver, C., Michaelis, S., Görlich, Y., & Wedekind, D. (2015). Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 30(4), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000078

Baxter, A. J., Scott, K. M., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 43(5), 897–910. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171200147X

Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011

Blakeley-Smith, A., Meyer, A. T., Boles, R. E., & Reaven, J. (2021). Group cognitive behavioural treatment for anxiety in autistic adolescents with intellectual disability: A pilot and feasibility study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(3), 777–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12854

Brent, D. A., & Kolko, D. J. (1998). Psychotherapy: Definitions, mechanisms of action, and relationship to etiological models. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022678622119

Burton, P., Palicka, A., & Williams, T. I. (2017). Treating specific phobias in young people with autism and severe learning difficulties. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X17000241

Byrne, G., & O’Mahony, T. (2020). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism spectrum conditions (ASC): A systematic review. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.10.001

Cachia, R. L., Anderson, A., & Moore, D. W. (2016). Mindfulness in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and narrative analysis. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-016-0074-0

Camm, S., Porter, M., Brooks, A., Boulton, K., & Veloso, G. C. (2021). Cognitive interventions for children with acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(4), 621–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1722714

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Autism Spectrum Disorder. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm.html

Charman, T., Pickles, A., Simonoff, E., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2011). IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: Data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Psychological Medicine, 41(3), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000991

Chok, J. T., Demanche, J., Kennedy, A., & Studer, L. (2010). Utilizing physiological measures to facilitate phobia treatment with individuals with autism and intellectual disability: A case study. Behavioral Interventions, 25(4), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.312

Cooray, S., & Bakala, A. (2005). Anxiety disorders in people with learning disabilities. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 11(5), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.11.5.355

Dagnan, D., Jackson, I., & Eastlake, L. (2018). A systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(11), 974–991.

David, D., Cristea, I., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychological therapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

Delli, C. K. S., Polychronopoulou, S. A., Kolaitis, G. A., & Antoniou, A. S. G. (2018). Review of interventions for the management of anxiety symptoms in children with ASD. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 95, 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.023

Derogatis, L.R. (1975). Brief Symptom Inventory. Clinical Psychometric Research

Dunn, W. (1999). Sensory Profile: Examiner’s manual. Psychological Corporation.

Esbensen, A. J., Rojahn, J., Aman, M. G., & Ruedrich, S. (2003). Reliability and validity of an assessment instrument for anxiety, depression, and mood among individuals with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:jadd.0000005999.27178.55

Fodstad, J. C., Kerswill, S. A., Kirsch, A. C., Lagges, A., & Schmidt, J. (2021). Assessment and Treatment of noise hypersensitivity in a teenager with autism spectrum disorder: A case study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(6), 1811–1822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04650-w

Fynn, G., Porter, M., Borchard, T., Kazzi, C., Zhong, Q., & Campbell, L. (2022). The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for individuals with an intellectual disability and anxiety: A systematic review. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University.

Gobrial, E., & Raghavan, R. (2012). Prevalence of anxiety disorder in children and young people with intellectual disabilities and autism. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 6(3), 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/20441281211227193

Gobrial, E., & Raghavan, R. (2018). Calm child programme: Parental programme for anxiety in children and young people with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(4), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629517704536

Goncalves, D. C., & Byrne, G. J. (2012). Interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.010

Halim, A. T., Richdale, A. L., & Uljarević, M. (2018). Exploring the nature of anxiety in young adults on the autism spectrum: A qualitative study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 55, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.07.006

Howlin, P., & Magiati, I. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder: Outcomes in adulthood. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000308

Hronis, A., Roberts, L., & Kneebone, I. I. (2017). A review of cognitive impairments in children with intellectual disabilities: Implications for cognitive behaviour therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12133

Jennett, H. K., & Hagopian, L. P. (2008). Identifying empirically supported treatments for phobic avoidance in individuals with intellectual disabilities. Behavior Therapy, 39(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2007.06.003

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

Kerns, C. M., Kendall, P. C., Zickgraf, H., Franklin, M. E., Miller, J., & Herrington, J. (2015). Not to be overshadowed or overlooked: Functional impairments associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in youth with ASD. Behavior Therapy, 46(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.005

Kerns, C. M., Winder-Patel, B., Iosif, A. M., Nordahl, C. W., Heath, B., Solomon, M., & Amaral, D. G. (2021). Clinically significant anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder and varied intellectual functioning. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(6), 780–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1703712

Kerns, C. M., Kendall, P. C., Berry, L., Souders, M. C., Franklin, M. E., Schultz, R. T., ... & Herrington, J. (2014). Traditional and atypical presentations of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 44(11), 2851–2861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2141-7

Kester, K. R., & Lucyshyn, J. M. (2018). Cognitive behavior therapy to treat anxiety among children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 52, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.05.002

Kreslins, A., Robertson, A. E., & Melville, C. (2015). The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 22–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0054-7

Lam, K. S., & Aman, M. G. (2007). The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: Independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(5), 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0213-z

Lang, R., Regester, A., Lauderdale, S., Ashbaugh, K., & Haring, A. (2010). Treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders using cognitive behaviour therapy: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518420903236288

Lickel, A., MacLean, W. E., Blakeley-Smith, A., & Hepburn, S. (2012). Assessment of the prerequisite skills for cognitive behavioral therapy in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 992–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1330-x

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services.

Luscre, D. M., & Center, D. B. (1996). Procedures for reducing dental fear in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26(5), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172275

Lydon, H. O., O’Callaghan, O., Mulhern, T., & Holloway, J. (2015). A Systematic Review of the Treatment of Fears and Phobias Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0043-4

Maiano, C., Coutu, S., Tracey, D., Bouchard, S., Lepage, G., Morin, A. J., & Moullec, G. (2018). Prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders among youth with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 236, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.029

Matson, J. L., & Shoemaker, M. (2009). Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1107–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.06.003

Mayes, C. S. L., Aggarwal, R., Baker, C., Mathapati, S., Molitoris, S., & Mayes, R. D. (2013). Unusual fears in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(1), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.08.002

Meindl, J. N., Saba, S., Gray, M., Stuebing, L., & Jarvis, A. (2019). Reducing blood draw phobia in an adult with autism spectrum disorder using low-cost virtual reality exposure therapy. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(6), 1446–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12637

Mindham, J., & Espie, C. A. (2003). Glasgow anxiety scale for people with an intellectual disability (GAS-ID): Development and psychometric properties of a new measure for use with people with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00457.x

Moree, B. N., & Davis, T. E. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: Modification trends. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(3), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2009.10.015

Moskowitz, L. J., Walsh, C. E., Mulder, E., McLaughlin, D. M., Hajcak, G., Carr, E. G., & Zarcone, J. R. (2017). Intervention for anxiety and problem behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(12), 3930–3948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3070-z

Muskett, A., Radtke, S., & Ollendick, T. H. (2020). Brief, intensive, and concentrated treatment of specific phobia in a child with minimally verbal autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Case Studies, 19(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650119880271

Ollendick, T. H. (1983). Reliability and validity of the revised fear survey schedule for children (FSSC-R). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21, 685–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(83)90087-6

Perdices, Tate, R. L., & Rosenkoetter, U. (2019). An Algorithm to Evaluate Methodological Rigor and Risk of Bias in Single-Case Studies. Behavior Modification, 145445519863035–145445519863035. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445519863035

Perihan, C., Burke, M., Bowman-Perrott, L., Bicer, A., Gallup, J., Thompson, J., & Sallese, M. (2020). Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for reducing anxiety in children with high functioning ASD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(6), 1958–1972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03949-7

Poornima, V., Poornima, M. N., Pradeep, A. J., & Kommu, J. V. S. (2019). Amenable for psychological interventions? Case report of a child with multiple developmental disabilities and challenging behaviours. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15(4), 92–103.

Prout, H. T., & Nowak-Drabik, K. M. (2003). Psychotherapy with persons who have mental retardation: An evaluation of effectiveness. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 108(2), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2003)108%3C0082:PWPWHM%3E2.0.CO;2

Reid, K. A., Smiley, E., & Cooper, S. A. (2011). Prevalence and associations of anxiety disorders in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(2), 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01360.x

Rivard, M., Terroux, A., Mercier, C., & Parent-Boursier, C. (2015). Indicators of intellectual disabilities in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2198-3

Rodgers, J., Wigham, S., McConachie, H., Freeston, M., Honey, E., & Parr, J. R. (2016). Development of the anxiety scale for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASC-ASD). Autism Research, 9(11), 1205–1215. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1603

Rosen, T. E., Connell, J. E., & Kerns, C. M. (2016). A review of behavioral interventions for anxiety-related behaviors in lower-functioning individuals with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 31(2), 120–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.1442

Rotheram-Fuller, E., & Macmullen, L. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychology in the Schools, 48(3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20552

Rutter, M., Bailey, A., & Lord, C. (2003). SCQ. The Social Communication Questionnaire. Western Psychological Services.

Scahill, L., Lecavalier, L., Schultz, R. T., Evans, A. N., Maddox, B., Pritchett, J., ... & Edwards, M. C. (2019). Development of the parent-rated anxiety scale for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(9), 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.10.016

Shabani, D. B., & Fisher, W. W. (2006). Stimulus fading and differential reinforcement for the treatment of needle phobia in a youth with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39(4), 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2006.30-05

Sigurvinsdóttir, A. L., Jensínudóttir, K. B., Baldvinsdóttir, K. D., Smárason, O., & Skarphedinsson, G. (2020). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for child and adolescent anxiety disorders across different CBT modalities and comparisons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 74(3), 168–180.

Simões, C., & Santos, S. (2016). Comparing the quality of life of adults with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60(4), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12256

Smith, I. C., Ollendick, T. H., & White, S. W. (2019). Anxiety moderates the influence of ASD severity on quality of life in adults with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 62, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.03.001

Spain, D., Sin, J., Linder, K. B., Mcmahon, J., & Happé, F. (2018). Social anxiety in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 52(C), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.04.007

Stern, J. A., Gadgil, M. S., Blakeley-Smith, A., Reaven, J. A., & Hepburn, S. L. (2014). Psychometric properties of the SCARED in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1225–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.008

Sukhodolsky, D. G., Bloch, M. H., Panza, K. E., & Reichow, B. (2013). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1341–e1350. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-1193

Tate, R. L., Perdices, M., Rosenkoetter, U., Wakim, D., Godbee, K., Togher, L., & McDonald, S. (2013). Revision of a method quality rating scale for single-case experimental designs and n-of-1 trials: The 15-item Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) Scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 23(5), 619–638.

Toscano, R., Hudson, J. L., Baillie, A. J., Lyneham, H. J., & McLellan, L. F. (2020). Development of the Macquarie Anxiety Behavioural Scale (MABS): A parent measure to assess anxiety in children and adolescents including young people with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 678–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.076

Ung, D., Selles, R., Small, B. J., & Storch, E. A. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(4), 533–547. https://doi-org.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0494-y

van Steensel, F. J., Bögels, S. M., & Dirksen, C. D. (2012). Anxiety and quality of life: Clinically anxious children with and without autism spectrum disorders compared. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.698725

Vasa, R., Carroll, A., Nozzolillo, L., Mahajan, M., Mazurek, A., Bennett, R., Wink, M., & Bernal, O. (2014). A systematic review of treatments for anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3215–3229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2184-9

Velting, O. N., Setzer, N. J., & Albano, A. M. (2004). Update on and advances in assessment and cognitive-behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.35.1.42

Vereenooghe, L., & Langdon, P. E. (2013). Psychological therapies for people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(11), 4085–4102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.08.030

Watts, S. E., Turnell, A., Kladnitski, N., Newby, J. M., & Andrews, G. (2015). Treatment-as-usual (TAU) is anything but usual: A meta-analysis of CBT versus TAU for anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.025

Weston, L., Hodgekins, J., & Langdon, P. E. (2016). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy with people who have autistic spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.08.001

White, S. W., Simmons, G. L., Gotham, K. O., Conner, C. M., Smith, I. C., Beck, K. B., & Mazefsky, C. A. (2018). Psychosocial Treatments Targeting Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents and Adults on the Autism Spectrum: Review of the Latest Research and Recommended Future Directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(10), 82–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0949-0

Winch, A. T., Klaver, S. J., Simpson, S., Calub, C. A., & Alexander, K. (2022). Identifying and treating anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorder/intellectual developmental disorder: A review. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7(1), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2021.2013139

Wolff, J. J., & Symons, F. J. (2012). An evaluation of multi-component exposure treatment of needle phobia in an adult with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26(4), 344–348.

Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Horowitz, J. D., Powers, M. B., & Telch, M. J. (2008). Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 1021–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.007

Wood, J. J., & Gadow, K. D. (2010). Exploring the nature and function of anxiety in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(4), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01220.x

World Health Organization. (2016). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (10th ed.). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en

Wright, K. P. (2013). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety in a man with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and social phobia. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-06-2013-0040

Zaboski, B. A., & Storch, E. A. (2018). Comorbid autism spectrum disorder and anxiety disorders: A brief review. Future Neurology, 13(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl-2017-0030

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the research assistants who participated in this project, Ms Qing Zhong and Ms Melindah Brunt.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazzi, C., Campbell, L. & Porter, M. Psychological therapies for anxiety in autistic individuals with co-occurring intellectual developmental disorder: A systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00371-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-023-00371-9