Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapies targeting the CD19 antigen have been associated with high and durable response rates in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). CAR-T cell therapies are commonly administered in the inpatient setting due to the average onset of cytokine release syndrome within the first 3 days post infusion, but there has been growing interest in delivering CAR-T cell therapies in the outpatient setting to overcome frequent hospital bed shortages and the high cost of inpatient care. Although this approach could improve access whilst catering to patient preference, it requires a multidisciplinary approach as well as careful patient selection. Herein, Dr. Foley and Dr. Kuruvilla discuss the case of a patient presenting with the ideal profile for CAR-T cell therapy referral whilst also determining the key attributes for eligibility from a clinician’s perspective. Solutions for successful outpatient management include proper education, caregiver support, and early referral to ensure a timely infusion. In conclusion, outpatient administration of CAR-T cell therapy in patients with DLBCLs should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

A vodcast feature is available for this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) that are refractory to primary and second-line therapies or that have relapsed after stem-cell transplantation could be candidates for CAR-T cell therapy. |

Administration of CAR-T cell therapy in the outpatient setting requires the introduction of rigorous monitoring programs incorporating healthcare professional education and caregiver support. |

Patients need to meet specific criteria to be eligible for outpatient treatment. |

Further referral programs need to be established to ensure timely infusion for eligible patients. |

Identification of a patient suitable for CAR-T therapy in the outpatient setting: A vodcast and case example. (MP4 487,305 KB)

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a vodcast feature, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25305859.

Vodcast Attendees and Introduction

Ronan: Welcome to our session entitled “Identification of a patient suitable for CAR-T therapy in the outpatient setting: A vodcast and case example.” My name is Ronan Foley. I’m a hematologist and professor at Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Center in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. I’m joined by my colleague, Dr. John Kuruvilla, who is at the Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto, Canada.

The Rationale behind Outpatient Management of CAR-T Therapy

Ronan: Today we’re talking about outpatient management of chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) cell therapy. And I would just start with two aspects that led to our commitment to setting up CAR-T exclusively in the outpatient setting. The first was that we were one of two sites in Canada that participated in the pivotal JULIET trial looking at the Kymriah product published by Stephen Schuster [1]. Interestingly, in that trial, even back in the beginning, outpatient care was allowable (permitted) on that trial. And because of our experience with outpatient autografts, we embraced that and in our commercial setting have continued to have outpatient CAR-T cell therapy. I think the second important thing that happened over time was that as we looked at real-world evidence using 4-1BB products, there was an interesting reduction in side-effects such that in the JULIET trial grade three/four cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was around 23% [1]. But in the real world, it plummeted down to just 5% [2]. Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) was even lower. And so, I think with that safety profile, we felt very comfortable in proceeding to an outpatient setup. And I’ll just ask you, John, what’s your sense about why did we see a reduction in some of these important side-effects?

John: Yeah. I think there are a couple of reasons for that, Ronan. I mean, first and foremost, we had increasing experience with managing these patients coming from the clinical trials’ data in certain settings, and maybe this was initially more with CD28 products, but showing that earlier administration of tocilizumab or corticosteroids could be done and could be done safely and wouldn’t result in any impairment of the effectiveness of CAR-T cells. And so that, along with, I think, some standardization of assessment for CRS and ICANS and harmonizing grading criteria, that really gave clinicians a lot of confidence with managing these patients and seeing that data that was very reassuring about lower rates of high-grade toxicity.

Ronan: The important reasons to consider this, certainly bed capacity and resource issues. And with so many CAR-T newer indications, one can envision there will be a lot of CAR-T as well as bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) activity happening. Cost. There is a paper referenced here by Lyman in JAMA 2020 suggesting that up to 40% cost saving can be achieved by establishing an outpatient CAR-T cell therapy [3]. So again, cost, as always, being an important thing. I think there is an element of patient preference. And certainly, patients prefer to be sleeping in their own bed and being managed as an outpatient if they can. But the really critical thing here is that you have a dedicated suitable caregiver that can take on all the tasks. And most importantly, being able to recognize early signs of toxicity to immediately seek medical attention. In terms of efficacy, I think CAR-T therapy is very exciting for its remission rates and the very durable, likely cured responses. And of course, that would happen whether they’re outpatient or inpatient. I think the elephant in the room here is the adverse events (AEs) and specifically the immune'specific AEs that you want to be able to recognize very early and act upon them. And so, strategies, aside from having a very good caregiver, additional strategies are being looked at to monitor heart rates and temperatures in the outpatient setting so you can get an early recognition of when problems are starting. And I think in the setup, really as we’re finding in CAR-T in general, identification/ patient selection is a critical thing that we engage a multidisciplinary team to be part of the outpatient CAR-T infrastructure. This is, as said, is an extension from what we do with autografts. And then the feasibility of outpatient administration I think we’ve been able to show. And, of course, there are publications to confirm that developing [1, 2, 4].

Case Report on DLBCL

Ronan: So, to talk about outpatient CAR-T cell therapy and to discuss with John, we have a case. And the case is of a patient in their 50s. So somewhat young. Refractory diffuse large germinal center B cell (BGC) subtype. They present with extranodal kidney and other non-lymphoid (stage 4B) disease. And they have a MYC translocation identified by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Limited comorbidities, some hypertension previous on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. And with that, John, I would just ask you in this presentation where do you see the FISH MYC mutation fitting into this patient’s care?

John: So, this is one of those patients you may need to worry a little bit more about, Ronan. Increasingly, FISH has been used to stratify patients for treatment. And MYC does potentially identify a higher risk subset of patients. Historically, even a single translocation might have been associated with inferior outcome. What we see now typically in the modern practice of managing large cell lymphoma, we’re largely being driven by two factors. And so, if these are patients that have either dual expression by immunohistochemistry of MYC along with B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) typically seen in activated B cell-like (ABC) subtype, those are patients that we know may have an inferior outcome with treatment. But the patient population that we still continue to worry a little bit more about are patients that not only have a MYC translocation but typically have a BCL2 translocation. So, the so-called double-hit. That might have implications for how you give primary treatment. You might prefer a regimen like dose-adjusted EPOCH-R. But, in a patient like this, you’ll often be using other clinical variables to drive your decision making about number of cycles of treatment and other things looking at still trying to give curative standard front'line treatment.

Ronan: At presentation, the patient presented with obstructive uropathy, widespread adenopathy. Core biopsies confirmed a DLBCL phenotype. The Ki-67 was 50–60%. So probably not a high grade or dual hit, as John suggests. The MYC was positive in 20–30% of cells. I think when it comes to CAR-T cell therapy, knowing that the lesions are CD19 positive in my mind is important, although maybe not absolutely necessary. But we certainly find that immunohistochemistry for CD19 can be variable. But using flow cytometry can give you a nice sturdy signal of CD19 positivity. So, a diagnosis of diffuse large B advanced stage. The positron emission tomography (PET) scan at diagnosis showed extranodal disease, kidney, pancreas, bladder, and colon. So, a very certainly extranodal disease, which would be quite worrisome. Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). I think a diagnostic lumbar puncture (LP) is required. Not sure if I’d use central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis, but I’d at least want to ensure that there’s no tumor in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). OK. So, this patient immediately required a nephrostomy tube and high-dose corticosteroids with tumor lysis monitoring. But then once stable, proceeded to six cycles of R-CHOP with interim computerized tomography (CT). Unfortunately, the end of therapy PET scan showed regrowth of peritoneal sites indicating primary disease. And so, at that point, transitioned to salvage therapy with platinum-based gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin (GDP), which is what we use here in Canada. The plan at that point was to head towards an autograft. After two cycles of GDP, the PET had a mixed response. And unfortunately, one area was showing signs of progression. And so, at that point, the patient was pivoted from autograft towards CAR-T cell therapy and Kymriah or tisagenlecleucel was chosen for this patient. John, can you just—at your site when you have a patient who’s heading to auto, pivoting to CAR-T, obviously you want to move quickly. But what sort of things come to mind in that scenario?

John: Yeah. I mean, it’s always a tough conversation, Ronan, to, in one aspect have to tell a patient that they just went through 6 weeks of therapy and unfortunately it didn’t accomplish what it was supposed to accomplish in terms of generating response, and then being able to present stem cell mobilization and moving towards a curative auto, potentially. But the other advantage to the clinician in this setting is this is a patient that’s known to you. You’ve got imaging available. Your transplant team knows the patient. And if, like in many of our practices, that team is often very closely integrated with the people that give CAR-T cell therapy as well, the pivot for the clinician is straightforward. So, your imaging is up to date. You’re aware of the patient. You’ve probably done baseline studies to reassure yourself about their fitness to go through with a more intensive therapy. You might actually have an apheresis booking already for those peripheral blood stem cells and may still be able to use that with a manufacturing slot to get your CAR-T cells made. So, knowing about the patient a little earlier always makes this easier. And it’s a more controlled situation, in a way, than that patient that may have been sent in from a local transplant program to you for CAR-T where you have to get up to speed much more quickly, as well as meet the patient and try to establish that therapeutic relationship.

Ronan: Anything you can do to reduce the time to get to CAR-T is absolutely critical.

Clinician’s Perspective: Patient Selection for Possible Outpatient CAR-T Cell Therapy

Ronan: Now, thinking about this case, and specifically is this a patient that we should be doing as an outpatient? There’s a few factors to consider. And the same is true for CAR-T in general. Ideally, we’re looking at patients with a low tumor bulk with a normal LDH. And they’re not patients who are having fast paced growth. Also, patients that are asymptomatic from the disease that we’ve identified by PET. John brought up an extremely important point about early referrals. In this case, really it’s as early as it can be, because it’s pivoting from the auto in the same institution. But sometimes they’re coming from one institution to another. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) is critical. In this case, ECOG is 0. We do check the inflammatory state of patients with C-reactive protein (CRP) in ferritin at least, sometimes other biomarkers. We have a very good look at the caregiver and whether the caregiver is going to be able to serve all the roles that are required in an outpatient setting. This patient hasn’t had a lot of prior therapy in a normal platelet count. Where we get nervous or perhaps pause perhaps with some of the older patients is if their functional capacity is somewhat reduced. If there’s a lot of comorbidities, we may elect to have the person stay in hospital. And anything that would point toward a risk for ICANS also may make us think about patients staying in. We do like to look at the T cell fitness of patients in general, but that really doesn’t apply to the decision of inpatient or outpatient. More so the decision to move forward with CAR-T. So again, patient selection is absolutely critical in CAR-T therapy in general, but sort of an added layer to this when you’re thinking about the outpatient. So we are seeking patients that are ideally set up for this.

Patient Case Study Management

Ronan: Now, in terms of this patient, we did decide to go outpatient. The patient was asymptomatic. So we did not need bridging. So, heading into it, hemoglobin 119 g/L, white count 2.8 × 109/L, platelets 123 × 109/L, a normal LDH, normal inflammatory markers, and a borderline creatinine at 125 μmol/L (49 mL/min/1.73 m2 glomerular filtration rate (GFR)). The ejection fraction was 68%. Really, there were no comorbidities heading in. ECOG 0. This patient lives out of town. So, they were booked into a hotel close to our institution with daily visits from days 1 to 10 helped by their caregiver, who in this case was excellent. The arrangements were made by the multidisciplinary team. The patient received (lymphodepletion) LD in the standard fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) dosing as it goes along with the Kymriah product. And on day 0 received 2.5 × 108 per kg of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) cells. No problems with the infusion. Again, of note, historically there has been some data from Schuster and the team that higher doses of CAR-T cells (range of 0.6 to 6 × 108 CAR-positive viable T cells/kg), may be associated with more toxicity [1]. But in this case, this dose of cells is fine. On day plus two with daily visits, patient developed new neck swelling. And CT demonstrated a new clot. We have central lines in place. And the patient required a Fragmin. And I just ask, John, how would that, as a clinician, what would you have thought about this and the ability to remain as an outpatient?

John: Yeah, so I think every time you’re assessing that patient daily in the clinic, there’s that decision of what is changed and what may be feasible in terms of managing someone in the outpatient setting. So, I think the key question you had shown earlier on a previous slide that blood counts had been pretty good at baseline. And I’d hope that the platelet count was still in a decent range. There’s tons of experience, as everyone knows, in being able to manage venous thrombosis in the outpatient setting with low-molecular-weight heparin or other agents. And so, I think you could feel pretty confident at this point in letting that patient go home with close follow-up and the usual warnings about monitoring for bleeding now on top of the other things to watch out for around the CAR-T procedure.

Ronan: I agree with John. That’s exactly what happened. And day plus four, they did get a temperature of 38.1 °C , which, of course, we all know is the hallmark of potential CRS. But of course, the other issue is, if they’re neutropenic, could it be a fever? So, this was really the test for us in this scenario. Had a temp. An hour later, it had come down. No hypotension. Patient wasn’t symptomatic otherwise. It maybe made a grade one CRS. And the markers were not really tremendously elevated at that point. We decided because the patient’s already on prophylactic antibiotics to leave it at that but with really aggressive surveillance while the patient was back home. So, we made that point. John, how would you have seen this playing out?

John: Agreed, Ronan. I think this is one of the most common situations we’re now dealing with in that patient, is this just routine fever post chemotherapy potentially associated with infection? Could this be the beginnings of CRS and ICANS? And I think even with that clot, is it just a little inflammation potentially from that even? And so, the reassuring improvement very quickly thereafter, being able to monitor for a couple of hours in the clinic, not associated with other worrisome symptoms, yeah, I think you’d feel pretty comfortable letting that patient go home again with close monitoring that caregiver at home and the ability to see them more quickly and certainly reevaluate them the next day as needed.

Ronan: Would you give them a dose of tociluzimab and send them home?

John: I think that’s always the question. I think with this specific example, when you look at the short duration of the fever, it only hit 38.1 °C. Nothing else to suggest any organ compromise or blood pressure issue. The markers as well seem to be pretty low at baseline and were continuing to be well managed. I think you'd feel quite comfortable with holding therapy and observing.

Ronan: So, throughout the journey, no ICANS. The immune effector cell encephalopathy (ICE) scores were 10 out of 10 throughout. This is a patient who, standardly, would receive acyclovir, fluconazole, levofloxacin up to day 30. They’d stay on Septra and acyclovir for up to a year. This case remained as an outpatient from days 1 to 10, transitioned to Monday, Wednesday, Friday to day 21, and actually back to their local referring institution by day 22. Just note there, and there’s a reference for a recent paper by Park and Nature Medicine, looking at anakinra as a potential prophylactic for ICANS [5]. But certainly in this case, that wasn’t ever an issue. In terms of outcome, a day 30 PET, which we like to use, had a near complete metabolic response (CMR). That was one lesion that was graded three, four. Probably a Deauville 3. But certainly a remarkable response. The patient, of course, has since gone on to be in complete remission (CR) for over 2 years. The IgG dropped a bit, it went under 4 g, so patient was started on prophylactic gamma globulin for the first 6 months, which we set up at home. So, this case highlights the feasibility of outpatient and aspects of the case, which are, as we know, in CAR-T extremely important. The LDH, the ECOG, inflammatory state were all very important.

A Brief Mention of Other Patients in the Outpatient Setting

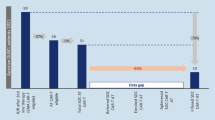

Ronan: I’ll just mention other patients who entirely exclusively were outpatient in our setting. Of course, it’s been many more. This was just in our beginning. But again, patients who really had no CRS or ICANS with the 4–1 BB Kymriah product. They all had low LDHs. They had low inflammatory markers. And, interestingly, of the patients shown here, I’m showing you five cases, all very kind of diverse in a way. Four out of five, 80% of them were in a complete metabolic remission by day 30. So interestingly, picking patients for outpatient may actually be picking patients who are destined to do very well at the same time.

Concluding Remarks

Ronan: So, in summary, you really have to think about your setup in your institution. And you have to set it up with outpatient in mind. The points of entry for education as patients come back. Does the emergency department, are they educated? Is the intensive care unit educated? The caregiver is absolutely critical if you’re going to do this. And that very much is working with our social work colleagues to assess the caregiver. You have to have dedicated bed on hold, as we did in autograft. Patient selection and early referrals are highly recommended. And, as John and I have said in the past, speed wins. So, you really want to get the CAR-T cells into the patient as soon as possible and really have a time-efficient process. I will bring this session now to a close. I want to thank my colleague, Dr. John Kuruvilla, for joining me today and for his important insights. I’d like to also thank the organizers for setting this up. Thank you very much.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this podcast as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the podcast.

References

Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56.

Bachier CR, Godwin JE, Andreadis C, Palomba ML, Abramson JS, Sehgal AR, et al. Outpatient treatment with lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) across a variety of clinical sites from three ongoing clinical studies in relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). Transplant Cell Ther. 2020;26(3):S25-26.

Lyman GH, Nguyen A, Snyder S, Gitlin M, Chung KC. Economic evaluation of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy by site of care among patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4): e202072.

Alexander M, Culos K, Roddy J, Shaw JR, Bachmeier C, Shigle TL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy: a comprehensive review of clinical efficacy, toxicity, and best practices for outpatient administration. Cell Ther Transplant. 2021;27(7):558–70.

Park JH, Nath K, Devlin SM, Sauter CS, Palomba ML, Shah G, et al. CD19 CAR T-cell therapy and prophylactic anakinra in relapsed or refractory lymphoma: phase 2 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2023;29:1710–7.

Editorial Assistance.

Editorial assistance with the preparation of the podcast discussion guide and abstract was provided by Chloe Schon and Jonathon Ackroyd, Springer Healthcare Ltd., UK. Funding for this assistance was provided by Sanofi.

Funding

Novartis Pharma AG provided funding for the creation and publication of the vodcast commentary. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was also funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ronan Foley and John Kuruvilla meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work, and have given their review and approval for the final podcast recording, discussion guide and transcript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Ronan Foley: Honoraria: Janssen, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Novartis Canada; Scientific Advisory Boards: Novartis, Roche Canada. John Kuruvilla: Honoraria: Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Beigene, Genmab Gilead, Incyte, Janssen, Karyopharm, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Seattle Genetics; Research support: Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI), Canadian Institutes of Heath Research (CIHR), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Canada, Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation, AstraZeneca, Kite, Merck, Novartis; Consultant: Abbvie, BMS, Gilead/Kite, Merck, Roche, Seattle Genetics; Scientific Advisory Board: Lymphoma Canada (Chair); Data Safety Monitoring Board: Karyopharm.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foley, R., Kuruvilla, J. Identification of a Patient Suitable for CAR-T Cell Therapy in the Outpatient Setting: A Vodcast and Case Example. Oncol Ther 12, 239–245 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-024-00272-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-024-00272-9