Abstract

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell (CAR-T) therapy has revolutionized advanced blood cancer treatment. However, preparation, administration, and recovery from these therapies can be complex and burdensome to patients and their care partners. Utilization of an outpatient setting for CAR-T therapy administration could help improve convenience and quality of life.

Methods

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with 18 patients in the USA with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma or relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 10 of whom had completed investigational or commercially approved CAR-T therapy and 8 of whom had discussed it with their physicians. We aimed to better understand inpatient experiences and patient expectations regarding CAR-T therapy and to ascertain patient perspectives on the possibility of outpatient care.

Results

CAR-T offers unique treatment benefits, particularly high response rates with an extended treatment-free period. All study participants completing CAR-T were very positive about their inpatient recovery experience. Most reported mild-to-moderate side effects; two experienced severe side effects. All said that they would opt to undergo CAR-T therapy again. Participants felt that the primary advantage of inpatient recovery was immediate access to care and on-going monitoring. Perceived advantages of the outpatient setting were comfort and familiarity. Because immediate access to care was seen as crucial, patients recovering in an outpatient setting would seek either a direct contact person or phone line for assistance if needed.

Conclusion

As institutions become more experienced with CAR-T therapies, outpatient care may help reduce financial strain. Patient input can help institutions improve the outpatient experience and ensure safety and effectiveness of CAR-T programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell (CAR-T) therapies hold promise for the treatment of hematological malignancies; however, preparation, administration, and recovery from these therapies can be complex and burdensome to patients and their care partners. |

Outpatient administration of CAR-T therapies may provide flexibility in the care setting, but implementation requires improved understanding of patient experiences during and after CAR-T administration. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients who had completed CAR-T therapy or had discussed it as an option with their healthcare providers had a positive perception of CAR-T therapy and highlighted the importance of immediate access to care and ongoing monitoring during recovery. |

Institutions interested in administering CAR-T therapies in an outpatient setting should incorporate patient input into their approach to ensure the safety and effectiveness of CAR-T programs. |

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell (CAR-T) therapy involves collecting and modifying patients’ T cells to attack specific antigens on cancer cells. These modified cells are expanded to a dose of several million copies and then reinfused several weeks later. Several CAR-T immunotherapies have now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration [1] and have revolutionized therapy for advanced blood cancers such as lymphoma, myeloma, and leukemia. CAR-T centers have been challenged with optimizing the treatment administration process for patients who face a new and daunting treatment modality that includes complicated procedures, life-threatening or debilitating toxicities, coordination of care between local providers and distant specialists, disruptive travel and lodging logistics, and burden on caregivers. CAR-T centers must also find ways to ease the financial burden on patients [2]. Most CAR-T therapies have been carried out in an inpatient setting. However, outpatient administration of CAR-T therapies may impact convenience and quality of life, and there is an emerging trend toward transitioning CAR-T therapy administration to an outpatient setting in the USA [3, 4]. We sought to understand patients’ perspectives related to inpatient care and a possible outpatient approach.

The site of care for the administration of CAR-T therapy—either inpatient or outpatient—is typically dependent on several product, patient, and institutional factors. The most common side effect of CAR-T therapy is cytokine release syndrome (CRS) [5], an immune response characterized by symptoms ranging from mild (fever, chills, fatigue, etc.) to severe (alterations in blood pressure and heart rate, organ damage, and possible death). Because CRS is potentially life threatening, patients must be monitored closely by healthcare providers or caregivers who can initiate supportive treatment immediately if needed. The average onset of CRS after CAR-T infusion varies among products from approximately 2 to 7 days [6,7,8,9,10,11], and this delay allows patients to recover initially for several days in a nearby, lower-cost setting, such as a hotel, before symptoms require admission. Patient factors also play a role in determining the appropriate care setting [12]. Comorbidities, age, fitness, and disease burden may be correlated with CRS severity, and availability of capable caregivers and insurance coverage may also influence decisions about the care setting. Furthermore, institutions must be capable of supporting CAR-T patients in either setting [13]. Efficient processes and adequate resources to oversee patients outside of an inpatient setting must be established, and inpatient capacity must be carefully calculated. Because of these various factors, institutional policy, rather than patient choice, currently dictates decisions about the CAR-T care setting.

The objective of this qualitative research was to better understand patients’ experiences and expectations regarding CAR-T therapy care in an inpatient setting and to obtain their perspectives on possible outpatient care. These insights can help guide other patients and caregivers who are contemplating CAR-T therapy and inform CAR-T centers that are pursuing alternative care settings to improve patient experience and quality of life.

Methods

This study was exploratory in nature, designed to gather information about the experiences and needs of patients across multiple centers in the USA. Inclusion criteria included adult patients diagnosed with either relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma or relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Two types of patients participated in this study: (1) patients who had recently completed CAR-T therapy through a clinical trial or in a commercial setting (n = 10; 7 completed therapy in 2021, 3 completed before 2021) and (2) patients who had discussed CAR-T therapy with their providers as a potential treatment option (n = 8). All participants spoke English and resided in the USA. Participants were predominately female (n = 13), white (n = 15), and college-educated (n = 15).

This study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study protocol was reviewed by Sterling Institutional Review Board (IRB), and a certificate of exemption was issued as nonhuman subjects research (IRB ID #9112). All patients signed an informed consent form for participation in the interviews and publication of responses. In addition, patients received a stipend ($100 ) for their participation.

Participants were recruited on a rolling basis, with interviews taking place from 6 October 2021 to 13 January 2022. Most participants (n = 13) were enrolled via a recruitment firm (Rare Patient Voice). However, as CAR-T therapy is an emerging therapy and recruiting was difficult, we also used snowball sampling [14] to supplement our recruitment efforts (n = 5). In our case, snowball sampling involved asking individuals who had completed the study to refer us to others or to post an announcement in their local patient support groups on our behalf. These additional recruiting efforts enabled us to meet our recruitment goal of 18 total participants, which is similar to the number of patients enrolled in other qualitative studies [15, 16].

Participants took part in a 60-min individual interview conducted online (using the platform Discuss.io). A professional moderator conducted the sessions. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed, and transcripts were thematically analyzed by a senior qualitative researcher.

During the sessions, participants who had completed CAR-T therapy were asked to describe their overall timeline for and experiences regarding CAR-T therapy, with a particular emphasis on the recovery period. Participants who had discussed CAR-T therapy with their physician but not undergone it were asked to describe their understanding of CAR-T therapy recovery options. Both groups were asked to identify perceived differences in recovery settings (inpatient versus outpatient), to discuss their decision-making processes related to recovery options, and to identify helpful supports for outpatient recovery.

Results

Three main topical themes emerged from these patient conversations: (1) high expectations for CAR-T therapy, (2) positive recovery experiences with limited experience of outpatient recovery, and (3) the importance of safety considerations and close monitoring for outpatient recovery.

Theme 1: High Expectations for CAR-T Therapy

Participants who had discussed CAR-T therapy with their physicians noted that they were in frequent conversation with providers about their next treatment option. One noted, “I’m always looking ahead at what the next possible therapy might be, because I assume that I’m going to have another relapse.” Typically, they had been discussing CAR-T with their providers for several years.

CAR-T was seen as offering some unique treatment benefits, mainly the lack of ongoing therapy in the period immediately after receiving CAR-T therapy. Participants considering CAR-T called it “successful,” “effective,” and “fantastic,” and noted that it created a “deep response,” allowing patients to be “maintenance free.” One participant said, “I’m looking forward to having a pause in treatment and some quality of life come back to me.”

These participants noted that it is a complex procedure that requires monitoring (similar to stem cell transplantation), though a few said that the side effects from stem cell transplantation are more severe. They were aware of possible side effects, including seizures, tiredness, neurotoxicity/neurologic issues, and CRS, with most noting that patients who receive CAR-T therapy are typically admitted to the hospital for observation.

Study participants who had discussed CAR-T therapy with their physicians and those who had completed therapy reported typical travel times from their home to the CAR-T center of approximately an hour (though some traveled much farther); travel to a center is anticipated as a part of therapy. Those who had completed therapy reported making three to five visits (over approximately 3 months) to their CAR-T center before receiving the infusion.

Immediately before receiving the infusion, participants reported feeling either excited or nervous: excitement related to their hopes for CAR-T therapy’s effectiveness, whereas nervousness related to uncertainty over what might happen. In contrast, the actual infusion was described as “anticlimactic” or a “nonevent.” One participant said: “It’s the most anticlimactic thing ever, because you’re preparing for this all this time, and you put so much hope into it. … And as soon as they put it there and they plug in the intravenous therapies, the volume is basically lost in the tubing.”

Theme 2: Positive Recovery Experiences and Limited Experience with Outpatient Recovery

Participants who had completed CAR-T therapy noted that their center dictated their recovery options; inpatient recovery was most common, with only two participants reporting that they had the option for outpatient recovery. Only one participant began the recovery period in an outpatient setting (and was admitted on day 4 because of a fever). Most were required to be admitted for 1–2 weeks after receiving their initial infusion. After discharge, many were told that they needed to stay close to the center (e.g., in a nearby hotel) for an additional period of time.

All participants were very positive about their inpatient recovery experience and reported a high level of care. They said that nurses checked on them every 1–4 h (more often initially or if they were experiencing side effects) and that they were seen by a physician at least once a day. Although they were pleased overall with their inpatient experience, their most consistent complaint related to sleep, as frequent monitoring interrupted their rest. Participant comments about their care included “Top-notch. I have a really good care team…literally 24/7, monitoring me, checking up on me,” and “When I was in the hospital, it was pretty much anything I needed. I mean, if you’re hungry, thirsty, hot, cold—whatever you need, they take care of it.”

Of the ten participants who had undergone CAR-T, most (n = 8) reported mild-to-moderate side effects and hospital stays of 9–15 days. Mild side effects included fatigue, weakness, and low fever; moderate side effects included low blood pressure and liver issues. Two experienced severe side effects that necessitated longer hospital stays of approximately 4 weeks.

Overall, participants reported a positive experience with CAR-T therapy. They described it as “a good experience,” “a game-changer,” “very positive,” and “smoother than anticipated.” All participants said that, based on their experiences, they would undergo CAR-T therapy again. One participant noted: “Before CAR-T therapy, I probably spent 10 h, 11 h, more, a week, traveling to and from my doctor’s office, sitting and getting infusions. … My whole life was consumed. For the most part, I couldn’t make any plans. I couldn’t go places. I couldn’t travel because I was tethered to my infusions and my doctors. I mean, this is like getting your life back.”

Theme 3: Importance of Safety Considerations and Close Monitoring for Outpatient Recovery

Although participants tended not to have an option regarding where to recover, several were open to the idea of recovery in an outpatient setting. One participant who had discussed CAR-T therapy with their physician said, “I would have probably a lot of questions. … Is it safe to go home? Is it safe to stay here? What behooves me the best? What do the professionals think? What does my doctor think?” Another who had completed CAR-T therapy with only minor side effects noted, “If I were going to do this again, I would definitely do it outpatient. … Because I’ve been down the path, I know what to expect. I know what would be concerning.” However, the majority of participants who had completed CAR-T therapy were glad to have recovered in an inpatient setting.

Participants were asked to consider the perceived advantages and disadvantages of recovery in an inpatient versus outpatient setting (Table 1). Responses indicated that the primary advantage of inpatient care recovery was immediate access to care, along with a high level of monitoring. Participants who recovered inpatient after CAR-T therapy felt very safe in this setting, and the overall quality of care was seen as very high. One participant noted, “They’re trained to recognize the issues that come out of CAR-T, and if they detect something, (a) they recognize it, and (b) they can handle it right away.” In contrast, the main advantages of the outpatient setting were considered to be comfort and familiarity. One noted, “It’s certainly much more comfortable in your own home, in your own bed, and having just the comforts of that versus being in a hospital bed and … being woken up at all hours of the day and night.”

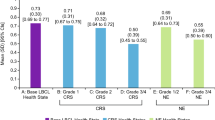

Study participants were asked to engage in a prioritization exercise to identify their primary considerations if given the option to select a recovery setting (Fig. 1). Their most important considerations related to safety, including the desire for immediate access to care and the ability to quickly address any potential side effects. A secondary concern was the overall care environment (including patient comfort) and impact on their caregiver (inpatient care was seen as less burdensome for the caregiver). Their least important considerations related to support services, as well as to cost and coverage. Although participants recognized that outpatient CAR-T therapy recovery reduces costs from a systems perspective, they saw that reduction as cost savings for the payer. One noted, “Affordable for whom? Because when you go outpatient, it’s putting a lot more burden on things that you don’t get reimbursed for.”

Participants were asked to identify key supports that they would desire in an outpatient setting. They were asked this question twice: first on an unprompted or open-ended basis and second in response to a prompted list of possible supports (Table 2). On an unprompted basis, they most often mentioned visits from providers to monitor their recovery, the necessity of a dedicated caregiver, and meal support. On a prompted basis, they were interested in almost all supports, including proper training and support for caregivers to monitor their care in an outpatient setting. Critically, they need someone with them who is trained to recognize emerging issues, and they need an immediate pathway to care should their condition necessitate a return to the inpatient setting. One commented, “I think the most important thing would be being able to access immediate medical help if it were called for. … Being able to phone somebody, a real person, and being able to talk to that person is very important.” Another noted, “You better have a nurse there for at least a couple days in the house until you stabilize. … You better have at least a caregiver in your home, someone there who knows how to dial 911 and won’t freak out or someone who knows how to help you take your temperature or whatever has to be done.”

Because immediate access to care is seen as vitally important, patients recovering in an outpatient setting would be seeking either a direct contact person they can call for assistance (e.g., a caseworker or social worker) or a direct phone line to reach a healthcare provider who could help them access care immediately if necessary. One participant noted, “I wouldn’t want to have to call in and be placed on hold. … I would want a direct line to help if I needed it.”

Discussion

This qualitative research analyzes the sentiment of 18 patients who had completed CAR-T therapy or had discussed it with their physicians. Although we focused on the recovery setting immediately after CAR-T administration (the first 2 weeks), additional insights were captured regarding their experience and expectations of CAR-T therapy.

CAR-T therapy is indicated for patients with lymphoma or myeloma who have relapsed or become refractory to a number of prior therapeutic regimens [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Participants in this study expressed understanding about CAR-T therapy as a possible treatment option. Participants who had discussed CAR-T therapy with their physicians but not received it appeared to be educated about the main side effects, procedures, and logistics, which included travel to and recovery near the CAR-T center. As a frame of reference, most participants who had received CAR-T therapy had also received prior stem cell transplantation, and they noted that the CAR-T experience was much easier and more tolerable than anticipated. All participants expressed excitement for the promise of a long treatment-free period after CAR-T therapy, understanding that it may not be a complete cure. However, few were knowledgeable about the possibility of recovery in an outpatient setting, and only one experienced recovery as an outpatient. Some participants understood that their poor health or inadequate caregiver support most likely required them to recover in the hospital, but others were unaware that outpatient recovery was even a possibility. We did not explore the root cause of these considerations and speculate that outpatient capabilities most likely had not been established at their institutions or that policies and protocols did not allow for outpatient care.

Even though only one study participant who had received CAR-T therapy experienced recovery in an outpatient setting, all participants discussed their concerns, potential benefits, foreseen challenges, and desires for optimal care in that setting. In the hospital, close oversight and support by healthcare professionals provide reassurance of safe recovery. Minor drawbacks were raised, such as sleep interruptions and visitation constraints, as well as concerns about hospital-acquired infections, but inpatient recovery was perceived quite favorably overall. Conversely, participants expressed that, although these disadvantages would be limited in the outpatient setting, the most important requirements that must be established in an outpatient setting are frequent monitoring checkpoints and clear, expedited processes to receive timely support when indicated, comparable to that received in the inpatient hospital setting.

In the original research plan, we aimed to include a small sample of interviews with caregivers to capture the perspective of another integral stakeholder in patient care. Unfortunately, recruitment of caregivers was too limited for analysis of this perspective; however, participants provided perspectives about their caregivers. Specifically, they expressed that inpatient recovery provided much-needed relief to caregivers and that the outpatient setting would most likely increase caregiver burden. Caregivers, for example, would need special training on how to monitor and identify symptoms of adverse events, such as CRS, and instruction on what actions to take when these events occur. Therefore, caregiver support in the outpatient setting is recommended.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Because few study participants had direct experience with recovery from CAR-T therapy in an outpatient setting, they were asked to project how they might feel. Although participants who had not completed CAR-T could draw on their previous experiences recovering inpatient from other treatments (e.g., many had undergone stem cell transplantation), such experiences may not be an appropriate frame of reference for CAR-T therapy recovery. Additionally, several participants who had completed CAR-T therapy did so as part of a clinical trial; therefore, their experiences may have differed from those of patients who completed CAR-T therapy outside a trial setting. Finally, because this was a difficult-to-recruit patient population, the use of snowball sampling may also have influenced our results.

Conclusion

CAR-T therapy offers new hope to patients for whom multiple prior lines of treatment have failed but who require close oversight and management to mitigate unique clinical toxicities. As institutions in the USA become more experienced with these products and seek to reduce costs, outpatient care may impact patient and caregiver experience and quality of life. This qualitative research study found that participants who were considering or who had received CAR-T therapy recalled few drawbacks to the inpatient environment, which provided high assurances of safety, very good support and comfort from staff, adequate amenities, and welcome relief to caregivers. While imagining alternative recovery in a hotel or residence close to the hospital, participants expressed that oversight and processes comparable to those provided as an inpatient (e.g., frequent monitoring, expedited transport and admission to hospital for CRS treatment, adverse-event training for themselves and caregivers) are critical and must be replicated. Additional services, such as the provision of meals, would further improve the outpatient experience. As more CAR-T therapies enter the market, and as providers become more comfortable with managing adverse events of this drug class, outpatient capabilities may provide additional options for care. Patient input will not only improve the outpatient experience but will also help institutions ensure the safety and effectiveness of their CAR-T programs.

References

Sengsayadeth S, Savani BN, Oluwole O, Dholaria B. Overview of approved CAR-T therapies, ongoing clinical trials, and its impact on clinical practice. EJHaem. 2022;3(suppl 1):6–10.

Cusatis R, Tan I, Piehowski C, et al. Worsening financial toxicity among patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy: a mixed methods longitudinal study [abstract]. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):567.

Borgert R. Improving outcomes and mitigating costs associated with CAR T-cell therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(13 suppl):S253–61.

Mikhael J, Fowler J, Shah N. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies: barriers and solutions to access. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:800–7.

Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. 2022. https://www.lls.org/treatment/types-treatment/immunotherapy/chimeric-antigen-receptor-car-t-cell-therapy. Accessed 21 April 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. KYMRIAH (tisagenlecleucel). 2021. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/kymriah-tisagenlecleucel. Accessed 21 April 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. TECARTUS (brexucabtagene autoleucel). 2022. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/tecartus-brexucabtagene-autoleucel. Accessed 21 April 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. YESCARTA (axicabtagene ciloleucel). 2022. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/yescarta-axicabtagene-ciloleucel. Accessed 21 April 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CARVYKTI. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/carvykti. Accessed 21 April 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. ABECMA (idecabtagene vicleucel). 2021. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/abecma-idecabtagene-vicleucel. Accessed 21 April 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BREYANZI (lisocabtagene maraleucel). 2021. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/breyanzi-lisocabtagene-maraleucel. Accessed 21 April 2022.

CAR-T Cell Science. Defining CAR T associated toxicities. 2022. https://www.cartcellscience.com/car-t-associated-toxicities/. Accessed 21 April 2022.

Shaw G. Hospitals still grappling with $1 M+ price tag for CAR-T Rx. Pharmacy Practice News. 2021. https://www.pharmacypracticenews.com/Clinical/Article/10-21/Hospitals-Still-Grappling-With-1-M-Price-Tag-for-CAR-T-Rx/64913?ses=ogst. Accessed 21 April 2022.

Naderifar M, Goli H, Ghaljaie F. Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev Med Educ. 2017;14(3): e67670.

Carrasco S. Patients’ communication preferences around cancer symptom reporting during cancer treatment: a phenomenological study. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2021;12:364–72.

Bryant AL, Chan Y-N, Richardson J, Foster M, Owenby S, Wujcik D. Understanding barriers to oral therapy adherence in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020;11:342–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This study, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, were funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc and Legend Biotech, Inc.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance was provided by Carolyn Farnsworth, ELS, from MedThink SciCom, with funding support from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc and Legend Biotech, Inc.

Author Contributions

Todd J. Bixby, conceptualization, writing of original draft, funding acquisition, supervision; Christine J. Brittle, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, project administration; Patricia A. Mangan, writing, review, editing, visualization; Edward A. Stadtmauer, writing, review, editing, visualization; Lisa R. Kallenbach, conceptualization, writing of original draft. Authors received no compensation for the development of this manuscript.

Disclosures

Todd J. Bixby and Lisa R. Kallenbach are currently employed by Janssen. Christine J. Brittle received consulting fees from Janssen and research funding from CorEvitas LLC. Patricia A. Mangan received honoraria from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Legend, Novartis, Sanofi, and Takeda. Edward A. Stadtmauer received honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, GSK, Janssen, and Sanofi.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study protocol was reviewed by Sterling IRB, and a certificate of exemption was issued as nonhuman subjects research (IRB ID #9112). This study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All patients signed an informed consent form for participation in the interviews and publication of responses. In addition, patients received a stipend ($100) for their participation.

Data Availability

Data supporting this manuscript include recorded interviews and their transcripts. These materials are not publicly available for participant confidentiality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bixby, T.J., Brittle, C.J., Mangan, P.A. et al. Patient Perceptions of CAR-T Therapy in the USA: Findings from In-Depth Interviews. Oncol Ther 11, 303–312 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-023-00232-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-023-00232-9