Abstract

Introduction

To improve quality across levels of care, we developed a standardized care pathway (SCP) integrating palliative and oncology services for hospitalized and home-dwelling palliative cancer patients in a rural region.

Methods

A multifaceted implementation strategy was directed towards a combination of target groups. The implementation was conducted on a system level, and implementation-related activities were registered prospectively. Adult patients with advanced cancer treated with non-curative intent were included and interviewed. Healthcare leaders (HCLs) and healthcare professionals (HCPs) involved in the development of the SCP or exposed to the implementation strategy were interviewed. In addition, HCLs and HCPs exposed to the implementation strategy answered standardized questionnaires. Hospital admissions were registered prospectively.

Results

To assess the use of the SCP, 129 cancer patients were included. Fifteen patients were interviewed about their experiences with the patient-held record (PHR). Sixty interviews were performed among 1320 HCPs exposed to the implementation strategy. Two hundred and eighty-seven HCPs reported on their training in and use of the SCP. Despite organizational cultural differences, developing an SCP integrating palliative and oncology services across levels of care was feasible. Both HCLs and HCPs reported improved quality of care in the wake of the implementation process. Two and a half years after the implementation was launched, 28% of the HCPs used the SCP and 41% had received training in its use. Patients reported limited use and benefit of the PHR.

Conclusion

An SCP may be a usable tool for integrating palliative and oncology services across care levels in a rural region. An extensive implementation process resulted in improvements of process outcomes, yet still limited use of the SCP in clinical practice. HCLs and HCPs reported improved quality of cancer care following the implementation process. Future research should address mandatory elements for usefulness and successful implementation of SCPs for palliative cancer patients.

Plain language summary

When a patient has incurable cancer, it is beneficial to introduce palliative care early in the disease trajectory along with anti-cancer treatment. A standardized care pathway is a method to improve quality and reduce variation in healthcare. It can promote integrated healthcare services in palliative care, e.g. by specifying action points when the patient’s situation is changing. In this study, a standardized care pathway for cancer patients with palliative care needs was developed in a rural region of Norway. The pathway focused on patients’ needs and symptoms and on smooth transition between levels of care. An educational program and an information strategy were developed to ensure implementation. To evaluate the implementation, all activity regarding the implementation process was registered. Cancer patients and healthcare professionals were interviewed and answered questionnaires. One thousand three hundred and twenty healthcare professionals were exposed to the implementation strategy. One hundred and twenty-nine cancer patients were followed up according to the standardized care pathway. Despite different perspectives of care, it was feasible to develop a standardized care pathway for palliative cancer patients across care settings. A paper-based patient-held record was only found to be useful by a limited number of patients. An extensive implementation process was completed and resulted in improvements regarding healthcare professionals’ experience with the quality of cancer care in the region, but limited use of the care pathway in clinical practice. Further research should identify the most important elements for usefulness and successful implementation of the care pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Early integration of palliative care into oncology services and improved care coordination across levels are beneficial interventions. |

A standardized care pathway (SCP) can promote integrated healthcare. |

What was learned from the study? |

Developing an SCP across care levels in a rural region was feasible and improved healthcare professional-reported palliative cancer care. |

An extensive implementation process yielded limited use of the SCP in clinical practice. |

Elements for successful implementation need to be further investigated. |

Introduction

The benefits of early integration of palliative care into cancer care are evident [1,2,3]. However, the optimal content of early palliative care in oncology is not established, and little research has addressed services coordination across levels of care [4, 5]. For patients with complex medical conditions and functional decline, the transition between organizational levels is demanding and sometimes unsuccessful [6].

A standardized care pathway (SCP) is a method for planning and managing healthcare services [7,8,9]. Despite varying definitions, a care pathway aims to describe the service and the interventions, and the time frames and criteria for their use [8]. It aims to implement guidelines or evidence into practice, with the overall intent to improve treatment quality, reduce practice variations, and optimize resource utilization [8, 10]. Even rarely used in palliative medicine, an appropriately designed SCP has the potential to promote integrated healthcare services [5]. The method may improve services and facilitate integration of oncology and palliative care, e.g. by specifying compulsory actions at transition points of care [11,12,13]. The patient perspective in general, and patient-reported outcome measures specifically, are important elements of modern cancer and palliative care and recommended included in a care pathway [5]. Developing SCPs across healthcare levels can be challenging due to differences in organizational structures, competence, and perspectives of care [14].

Implementation research addresses both the intervention and the implementation strategy [15]. The goal of an implementation strategy is to change the behavior of healthcare personnel [16]. Any aspect of implementation may be considered, including factors influencing implementation, the implementation process, and results of the implementation [17]. Implementation outcomes include acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, coverage, and sustainability [17]. Thus, implementation research includes the perceived relevance, the actual fit, and the incorporation of an intervention into clinical practice [18].

Based on international, national, and regional initiatives to improve cancer care, the research project “The Orkdal Model: Development, implementation and evaluation of collaboration between specialist and community care within palliative cancer care” was launched (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02170168) [19, 20]. The project investigated full integration between oncology and palliative care, and between specialist and community healthcare services in a rural region of Mid-Norway [21]. The purpose was to improve quality of care for cancer patients and their families in this region, whether the patients were hospitalized, in community care, or in transition between the two levels. The intervention was an SCP, including both specialist and community care, and the current paper evaluates its implementation, addressing local government, provider organizations, front-line workers, and the public [18]. The following research questions were addressed:

-

1.

Was the standardized care pathway integrated in clinical practice and used as intended?

-

2.

Did the implementation strategy work, and which challenges were identified?

Methods

Context

The project was conducted between 2013 and 2019 [21]. An integrated oncology and palliative care outpatient clinic (hereafter: Integrated Clinic) was established in November 2012 in a hospital serving 97,000 inhabitants in rural municipalities. Founded on ideas conceived by authors of the current paper, the clinic was organized to treat patients at all stages of cancer and to integrate cancer and palliative care [21]. Its structure is described in Brenne/Knudsen et al., 2020 [21]. An agreement between the hospital and 13 municipalities described the collaboration for improved cancer care. The municipalities had between 980 and 11,000 inhabitants, and the longest driving time from the municipalities to the hospital was 2 h (130 km). At project start, there was no electronic communication between the levels, or within the municipalities.

Participants

For the collection of quantitative outcome variables, adult cancer patients diagnosed with advanced locoregional or metastatic disease, treated with non-curative intent, inhabited in one of the participating municipalities, and able to read and write Norwegian, were consecutively screened and recruited between November 2014 and December 2017, and followed up until death or December 2019 [21]. Healthcare leaders (HCLs) and healthcare professionals (HCPs) exposed to the implementation strategy and eligible for receiving questionnaires were identified by their leaders. Eligibility was fulfilled if being employed in one of the participating municipalities or at Orkdal Hospital, at least 18 years of age, and able to sign an electronic informed consent. Questionnaires were distributed in December 2014 (by email) and January 2017 (by mail). In the fall of 2015, questionnaires on the use of patient-held records (PHRs) were sent by mail to 102 nurses and nurse assistants, identified by their leaders to be working with cancer patients with palliative care needs. For the qualitative evaluation, HCLs and HCPs were interviewed in the spring of 2014 (during the development process of the SCP) and in the fall of 2015 (1 year after the SCP was launched). Patients were interviewed on their use of PHRs in the fall of 2015.

The intervention

Development of the intervention

We developed an SCP that described the activity at the Integrated Clinic at Orkdal Hospital and the interaction with hospital departments and community care [21]. The work was conducted in collaboration with the involved healthcare services and a patient representative (Table 1). Experiences from a previous pathway across levels of care were utilized [22]. Agreement on the current situation, description of patient flow and content of services, and identification of bottlenecks and challenges were essential steps in the development process (Fig. 1, Table 2). Because of different requirements at different stages of the disease trajectory, three sub-pathways were developed: (1) a pathway for referral to the Integrated Clinic, (2) a pathway during treatment and follow-up, and (3) a pathway for end-of-life care (Table 3). Each sub-pathway was adapted to each setting of care (home or nursing home, integrated outpatient clinic, hospital ward) and described actions to be taken depending on the patient’s situation. Extra emphasis was put on optimizing communication and transfer of medical information at care transitions. Trondheim University Hospital’s web-based comprehensive quality-and enterprise management tool for quality assurance, Extend Quality System (EQS), was applied [23].

Content of the intervention

The SCP guided treatment and care for all cancer patients with palliative care needs, regardless of cancer diagnosis and place of care (Table 3). Heterogeneous disease trajectories and inclusion of both community and specialist healthcare services necessitated focus on symptom burden, functional status, and individual needs [14]. Available palliative care tools were collected and adopted to the care pathway. Symptoms were assessed systematically, and the functional status and individual needs were evaluated interdisciplinarily in the light of the patients’ disease stage. Checklists and predefined medical chart templates were used to ensure quality and safety in care transitions and transfer of medical information. Telephone communication was used to secure the availability of HCPs with palliative care competence around the clock. Both patients’ and carers’ needs were assessed [5, 21, 24]. Nurse checklists were applied to facilitate use of the SCP. PHRs were introduced and included contact information, treatment plans, and medications [25]. The interaction between the three teams (palliative care, oncology and community care) is previously described [21]. The degree of involvement from each team depended on the identified care needs. The Integrated Clinic coordinated the care and the oncologist defined the appropriate treatment plan. The general practitioner (GP) and community health services were responsible for follow-up of the patient after discharge, with support from hospital palliative care personnel as needed. The SCP was linked to evidence-based guidelines and was accessible on public internet. The referral criteria to the SCP were: Cancer patients receiving life-prolonging treatment for locally advanced and/or metastatic disease, in need of symptom treatment and palliative care, and with Orkdal Hospital as their local hospital.

The implementation strategy

The implementation was conducted on a system level. The implementation strategy consisted of an information plan, appointment of local facilitators, and an education program (Fig. 2) [18]. The planning of the intervention started in 2013 [21]. Between 2014 and 2018 the implementation strategy was directed towards political and HCLs, HCPs, and the public. Political leaders were informed and attended public meetings to increase project focus. HCLs were committed through personal meetings and written information. HCPs were engaged in the development of the SCP and recruited as process facilitators. The facilitators promoted the use of the SCP and identified barriers hampering its use. An educational program was conducted for hospital and community HCPs (Supplementary Material). The program included comprehensive cancer care delivered by the means of an SCP and education on essentials of oncology and palliative care. Physicians, nurses, and other professionals with expertise in oncology and palliative care administered the program. To maximize knowledge dissemination, similar events were held at different locations. After participating in the education program, the HCPs were encouraged to teach their colleagues at their own workplace. In addition, a network of resource nurses facilitated care competence and collaboration [21]. The public, including patients and carers, were informed at meetings, by leaflets and newspaper articles, and online. Due to the slow inclusion rate of patients, the education program was prolonged with 2 years (from 2016 to 2018) without extra funding.

Evaluation of the intervention and implementation strategy

The intervention and the implementation strategy were evaluated according to implementation outcome variables and reported in line with standards for implementation studies [15, 17]. A mixed methods design was applied [26]. Nature and number of activities related to the intervention and implementation strategy were registered prospectively. Semi-structured interviews were performed with three different groups of informants. (1) Patients and HCPs were interviewed individually regarding their experiences with the PHR. The interview guide was developed by two of the authors (TIB and AKK). The questions were formed to explore patients’ and HCPs’ experience with the PHR and how it was used (Table 4, interview guide 1). TIB conducted the interviews. (2) HCLs and HCPs were interviewed individually on the intervention and the implementation strategy. The interviews were conducted during the development process and focused on implementation challenges. MNN and KR developed the interview guide (Table 4, interview guide 2) and conducted the interviews. (3) HCPs were interviewed individually regarding their experiences with the implementation of the SCP. MHJ and AKK developed this interview guide, and topics were HCPs’ experiences regarding success criteria and barriers for implementation, management anchoring and the SCP’s role in reaching central goals in palliative care (Table 4, interview guide 3). MHJ conducted these interviews. The sampling was purposive for all three groups to include a selection of patients, leaders, and representatives from different healthcare professions affected by the project [27]. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a stepwise-deductive induction approach (MNN and KR) [28] or systematic text condensation (TIB and MHJ) [29]. For the interviews where systematic text condensation was used for analysis, data collection was stopped when saturation was reached.

Acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, and feasibility

HCLs and HCPs were interviewed on the credibility, perceived fit, and practicality of the intervention and the implementation strategy, and on their intention to try the intervention as described above.

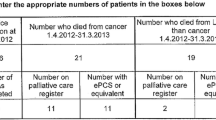

Fidelity, coverage, and sustainability

Both patients and HCPs reported on adherence to the use of PHRs. In addition to the semi-structured interviews, HCPs answered a questionnaire on knowledge and use of the PHR. Thus, the use of PHRs was analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively [26]. The delivery, reach, impact, and durability of the implementation strategy was evaluated by review of the conducted activities, written agreements, and by repeated interviews of HCLs and HCPs, as described above. At 2 months and 2.5 years after start of implementation, HCLs and HCPs answered a questionnaire on training in and use of the SCP, collegial teaching, confidence with opioid treatment and end-of-life care and use of symptom assessment tools (Table 5). Hospital admissions were registered prospectively. Use of nurse checklists in community care was evaluated after 3 years by personal contact with the respective municipalities.

Costs

Estimated costs of the intervention and the implementation strategy were based on knowledge of funding and structure of the local healthcare services.

Statistics

Change over time in healthcare providers’ knowledge and skills, and implementation and use of the SCP for palliative care, were secondary and exploratory outcomes of the Orkdal Model Study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02170168; primary outcomes published elsewhere). Therefore, power calculations for these outcomes were not done. Pre study, approximately 1300 HCPs were estimated to be asked for study participation, and with an anticipated response rate of up to 50%, a maximum of 650 healthcare providers would be included [30]. Descriptive statistics calculating frequencies were performed, and the Fisher’s exact test was used for group comparison. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) and Stata Statistical Software (Release16.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was applied.

Ethics and consent

The regional committee for medical research ethics approved the study (2014/212). All participants gave their consent to participate. HCLs and HCPs interviewed during the spring of 2014 did not provide written consent, as these interviews were part of a quality assurance project at St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital [31, 32]. The participants signed separate consent forms for the quantitative and qualitative data collection.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

Three hundred and nine cancer patients were potentially eligible for the SCP. Of these, 231 were approached for inclusion. One hundred and one patients declined participation and one withdrew consent. For data analysis, 129 patients were included. By the time of inclusion, 106 (82%) received anti-cancer treatment. Mean age was 70 years (range 38–92) and 81 (63%) were men. One hundred and eleven (86%) had metastatic disease, and 99 (77%) had a Karnofsky performance status of 80% or more [33]. Most common cancer diagnoses were prostate (23%), colorectal (13%), urinary organs except prostate (11%), upper gastrointestinal except pancreas (10%) and pancreas (9%). By the end of follow-up, 23 patients were alive.

Fifteen patients were interviewed regarding their experience with the PHR, six men and nine women. Mean age was 76 years, and all had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status I or II [34].

Characteristics of the professionals

In total, 1320 HCPs were identified by their leaders to be exposed to the implementation strategy and received questionnaires, of which 119 (9%) were employed in specialist care. Seventy-six (5.8%) were leaders, 69 (5.2%) physicians, 391 (30%) nurses, and 784 (59%) nurse assistants. Three hundred and fifty-five (of which 318 (87%) were from community care) signed informed consent to participate (response rate 27%). There were 21 drop-outs after the first round and 36 drop-ins after 2.5 years (Table 5). Thirteen percent of the participants from community care worked in Orkdal municipality, the municipality where the hospital was located. To assess adherence to PHR, separate questionnaires were sent to 102 HCPs working with cancer and palliative care in the region.

Altogether 60 HCPs were recruited as informants for semi-structured interviews, of which 43% were employed in specialist care. Fifteen percent were leaders, 35% physicians, 42% nurses, and 8% nurse assistants. Of these, 19 HCPs (10 from specialist care and nine from community care) involved in the development of the SCP underwent semi-structured face-to-face or telephone interviews in the spring of 2014. In the fall of 2015, 21 HCPs (eight from specialist care and 13 from community care) were interviewed face-to face regarding their experience with PHR, and 20 HCPs were interviewed (8 from specialist care and 12 from community care) about the implementation of the SCP.

Evaluation of the intervention

Prior to the implementation of the SCP, HCLs and HCPs identified three factors potentially limiting its success: organizational cultural differences, organizational factors, and decentralized decision-making (Supplementary Material). Organizational cultural differences included different perspectives on care and the purpose of an SCP. Organizational factors, such as different information and communications technology (ICT) systems, might represent a challenge for standardization. A community HCL reflected on this, “Our view of a patient is that the patient is primarily an inhabitant, who lives in the community, lives his life here, and will, independently of if he has cancer or chronic obstructive lung disease or whatever he has, have a good life here, both before and after treatment, and during treatment as well. But in hospital, you have, in a way, from ‘A to Z’ while the patient is admitted. So you don’t in a way see the world outside of the hospital. And then I think you deal with the patent in a different way, that our interaction with the patient is different”. An HCP in the community said it like this regarding the ICT systems, “ I do not see that I will go into St. Olavs Hospitals’ public and look at… click at home death, and then I’m supposed to find it all there. It must be a system in the community. […] It is different if you sit in an office, you know, very different. You have to think about that we’re out in the field large parts of the day.” Ultimately, decentralized decision-making and different priorities in specialist and community care were anticipated to reduce the commitment. As a GP said, “Our municipality has substantially bigger challenges regarding other patient groups. […] It is the municipality itself that has to decide what should be given priority, not specialist care.”

Both hospital and community HCPs acknowledged the SCP as a method to improve palliative cancer care and reported improved quality of care after the implementation. A GP said, “It has improved, it is probably because of the pathway, also for us who live outside of Trondheim, it is because the cancer outpatient clinic is here. Then they manage to implement this pathway much better.” In specialist care, the relevance and perceived fit were related to increased competence and improved structure. In community care, this view was counterbalanced by a worry for decreased attention to other diagnoses and needs for local adaptations. However, personnel in community care endorsed the patient-centered focus on function and individual needs. The workgroup agreed on a common strategy for the development and content of the SCP, and on the suitability both for everyday use and for reaching central goals in palliative care. Furthermore, the SCP was accounted feasible, provided sufficient training in its use. Factors facilitating the practicality included safe admission and discharge routines and patient involvement. The use of checklists and instant transfer of medical information were considered important factors for the intervention’s actual fit, whereas incompatible ICT systems were regarded as a challenge.

Fifteen cancer patients were interviewed on their experiences with the PHR. The patients reported limited use and limited benefit of the PHR. They preferred to use systems they were familiar with or did not feel the need to write. A patient said, “You take so good care of me that there is nothing special to follow up, so far”. Still, some patients appreciated the availability of an updated medication list.

Forty-five HCPs responded to a questionnaire regarding their experience with PHR, of which 32 were nurses and 13 nurse assistants (response rate 44%). Sixty-one percent were familiar with the PHR, but only one third took care of patients using it. The PHR use was restricted by a perception of limited benefit and uncertainty regarding accuracy, especially for medication lists.

Two hundred and eighty-seven HCPs (response rate 22%) reported on SCP use 2 months after project start and 152 HCPs (response rate 41%) after 2.5 years (Table 5). Fifty-three (18%) used the SCP at 2 months and 43 (28%) at 2.5 years (p = 0.02). During the same period, data from 325 hospital admissions were registered for the 129 patients. For 158 admissions (49%), relevant medical information was transferred the same day as discharge. At 3 years (in 2017), five out of 13 municipalities reported that they used the SCP nurse checklists.

The SCP was developed without dedicated funding. A task force revised the SCP three times during the study period based on revised guidelines and practices, user feedback, and personal experiences.

Evaluation of the implementation strategy

Interviews with HCLs and HCPs revealed that the implementation strategy was perceived as agreeable and relevant (Supplementary Material). Because of different perspectives, structures, and priorities in hospital and community care, dissimilar components of the implementation strategy were emphasized. Still, understandable relevant information, access to local experts, and SCP-related education were perceived useful. In addition, the informants considered purposeful interaction across levels of care and user involvement important for the feasibility of the implementation strategy. Local facilitators were regarded important for promoting patient safety through smoother transitions between places of care and more predictability for the patient and carer. Finally, the patient-centered focus was considered important for the actual fit of the implementation strategy.

Three major themes contributing to success or failure with the implementation of the SCP emerged from analysis of interviews with HCPs: “competence”, “coordination”, and “patient and carer” (Supplementary Material). HCPs reported increased competence, coordination, and quality of care after the implementation. The network of resource nurses and decentralized education were considered important for the successful dissemination of the SCP. However, the degree of implementation strategy success varied at different locations. Factors related to lack of success were suboptimal competence in palliative care, lack of process ownership, fear of giving one patient group priority, and limited involvement from the management. In addition, restricted funding and lack of an electronic SCP search function hampered the implementation.

Prospectively registered data regarding activities related to the intervention and implementation strategy showed that the implementation strategy was delivered as intended. The invited HCLs and HCPs attended the meetings, and the education program was conducted as planned. The number of participants of the education program was given in Supplementary Material. The majority of the participants were from community care and all municipalities had HCPs attending the education program. GPs from seven of 12 municipalities (the smallest municipality was served by GPs from the neighbor municipality) attended the education program. Thirty-seven process facilitators were recruited, five from hospital and 32 from community care. The SCP was revised yearly, because every 6 months turned out to be too resource demanding.

Two hundred and eighty-seven HCPs reported on training in use of the SCP 2 months after project start and 153 after 2.5 years (Table 5). Response rates were 22% and 41%, respectively. Eighty-three (29%) reported that they were trained in using the SCP at 2 months and 63 (41%) at 2.5 years (p = 0.01). One hundred and eight HCPs (response rate 8.2%) reported on collegial teaching 2 months after project start and 155 (response rate 42%) after 2.5 years. Thirty-four (31%) had performed collegial teaching at two months and 31 (20%) at 2.5 years (p = 0.04). For confidence with opioid treatment, 168 HCPs reported at two months and 95 after 2.5 years (nurse assistants excluded; response rates 37% and 47%, respectively). Seventy-two percent felt confident after 2 months and 85% after 2.5 years, respectively (p = 0.02), and for confidence with end-of-life care, 77% and 84%, respectively (p = 0.06; response rates 22% and 41%). Two hundred and ninety-three HCPs (response rate 22%) reported on use of symptom assessment tools 2 months after project start and 152 (response rate 41%) after 2.5 years. One hundred and forty-six (50%) applied symptom assessment tools at 2 months and 94 (62%) at 2.5 years (p = 0.02, Table 5).

The costs of the implementation strategy included grants for hospital employment of two nurses and one assistant for 12 months and two community care physicians for 19 months. In addition, community care nurses from ten municipalities received job training at the local hospital.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

An SCP across levels of care represented the intervention introduced to palliative cancer patients in a rural region of Mid-Norway by a comprehensive implementation strategy. Aspects of the intervention and the implementation strategy were evaluated using a mixed method approach. SCP as a method to improve palliative cancer care was found to be feasible among the HCPs. Despite different perspectives of care in specialist and community care, there was agreement on a common strategy for the SCP. Focus on patients’ function and needs, and not diagnoses, were endorsed. Sufficient training in its use was regarded important for the success of the SCP. Different organizational structures and ICT systems challenged implementation. The implementation strategy, running over a period for 4 years, was delivered as intended. Information and educational plans, appointment of local facilitators, and close collaboration with the regional network of resource nurses were essential parts of the strategy. Elements facilitating care integration were access to assessment tools, nurse checklists for care coordination, patient-held records, available treatment recommendations, and internet access. Nearly one third of the HCPs reported use of the SCP 2.5 years after the intervention was implemented. The use of essential elements of the SCP varied, and for only half of the admitted patients, medical information was transferred the same day as discharge. Forty-one percent of the HCPs reported that they had received training in using the SCP 2.5 years after the implementation was launched. Both HCLs and HCPs reported improved quality of care in the wake of the implementation. Limited project involvement and knowledge seemed to restrict the success of the implementation strategy.

Comparison with previous work

Already eleven years ago, the beneficial effects of early palliative care in cancer care were reported [1]. However, these first reports were from specialist care [1, 3, 35]. Since then, there has been a growing attention to the need of strengthening community palliative care to reach all in need of palliative care [36]. In our model, specialist care and community care cooperated through active use of the SCP making the trajectories as seamless as possible. The GPs, together with the community nurses, played an essential role in providing palliative care to the patients at home, strongly supported by the decentralized Integrated Clinic [21].

There is little research on care pathways in palliative medicine [12]. A clinical care pathway for palliative cancer patients may result in reduced symptom intensity [37]. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence to support end-of-life care pathways [38], and a cluster randomized trial on a generic care pathway for elderly patients in need of home care services was inconclusive [22]. Integrating care pathways into clinical practice is complex and depends on contexts both inside and outside of the organization [39]. To measure how and why a care pathway is working may be difficult [39]. In our study, the education program was pointed out as an important part of the implementation strategy. Participation in the education program was high. A Canadian project evaluating integration of early palliative care into routine oncology also highlighted the importance of training of HCPs to succeed with integration [40].

In addition to improved patient outcomes, an SCP may enhance competence and quality of care [41]. A systematic review and meta-analysis on integrated outpatient oncology and palliative care services reported improved quality of life, symptom burden, and survival [4]. In the current study, even with the low response rates, the quantitatively evaluated implementation strategy outcomes indicated an increase in HCP-reported confidence with opioid treatment and use of assessment tools. However, increase in confidence with end-of-life care did not reach statistical significance and there was a decrease in collegial teaching during the study period. Pre-study level of confidence and competence might influence the results.

A multinational cluster randomized trial studying an in-hospital care pathway found no significant effect on the primary outcome, which measured the communication and relationship between HCPs [41]. This may be explained by the time and complexity of interventions needed to improve interprofessional relations [41]. In our study, after implementation medical information was transferred at discharge only for half only the evaluated patients. This despite the emphasis put on communication in transitions of care in the SCP.

Study strengths and limitations

We applied a mixed methods design. A mixed methods design combines quantitative and qualitative approaches and is considered particularly suitable for implementation research [17]. The combination of methods provided opportunities for measuring the implementation of the intervention and for understanding the process [26]. The design also made possible a comparison of data collected by different methods [26]. In addition, the design gave an opportunity to monitor the implementation process over time and to compare anticipated and experienced challenges regarding the implementation strategy [42]. Our study described recommended intervention and implementation strategy outcomes, according to standards for reporting implementation studies [15]. However, the evaluation was conducted among small fractions of the included patients and affected HCPs, and self-reported data were used. This raises the question whether the samples were representative for the populations from which they were drawn, as few measures were made to reduce the risk of selection bias [43, 44]. Additionally, the relative response rates dropped during the study period. The questionnaire response rate was 27% at the first survey, and only those who signed informed consent received the second survey. Retrospective review of patient records regarding the use of the SCP may have provided a more reliable result [45]. The number of HCPs was tenfold the number of patients, limiting the plausible contact with patients included in the SCP for each respective HCP. Furthermore, less than one percent of the nurse assistants were interviewed. This group of HCPs constituted almost 60% of the recipients of the implementation strategy. Nurse assistants may represent HCPs benefiting from the implementation of the SCP. Finally, no carers were included in the evaluation of the intervention or the implementation strategy.

Implications and further work

The effectiveness of a patient-held record is dependent on it being used both by patients and HCPs [25]. In our study, patients and HCPs reported limited use of the PHR. Based on these findings, no definitive recommendations regarding the benefit of PHRs in integrated oncology and palliative care pathways can be provided. With electronic transfer of medical information, the benefit of a paper-based PHR could further be questioned.

Checklists are applied to improve standardization and reduce preventable errors, and the use of palliative care checklists may improve documentation [46]. Effective implementation of checklists is dependent on a coordinated effort from both HCLs and HCPs [47]. In the current study, only five out of 13 municipalities reported use of the nurse checklists after 3 years. Thus, the implementation strategy provided limited sustainability on this matter. Possible reasons for this attrition were that the municipalities had their own checklists or an incompatible ICT system. Future work must address the creating of more enduring structures supporting the implementation of new standards [47]. This may be challenging due to different priorities and standards in specialist and community healthcare services, as reported in our study and by others [14].

Efforts to implement complex interventions interact with individuals, collectives, organizations, and political and economic systems [48]. Reasons for failure may be related to lack of effect within the context tested, not meeting the needs of the stakeholders, or related to contextual instability, such as key staff replacement and insufficient funding [48]. In our study, the SCP was developed bottom-up, which one could believe would increase its use [49]. We observed an overall absolute improvement in the quantitatively collected implementation strategy outcomes of about 10% (except for collegial teaching). The clinical relevance of these improvements can be questioned. We did not predefine a satisfactory program fulfilment rate. A retrospective study evaluating the process of implementing a care pathway integrating oncology and palliative care at Oslo University Hospital found that the care pathway was not used as intended in terms of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [45]. The authors of this study recommended a more complex strategy to implement the use of PROMs in oncology. In our study, interviews with HCPs revealed that especially different ICT systems and variable management anchoring were barriers that should be more strongly addressed in the future. Enhanced follow-up of the process facilitators may also have improved the outcome, and one may speculate if change in key staff and lack of funding contributed negatively. The SCP was created mainly by staff from specialist care (Table 1), another factor possibly contributing negatively to implementation. Still, both HCLs and HCPs reported quality improvements after the implementation of the SCP, underlining the potential benefits of the approach. Future research must address the essentials of an integrated pathway in palliative cancer care, the necessary content of a successful implementation strategy, and measurement properties of instruments measuring integrated care [50].

Almost 40% of the included municipalities reported interest in continuing the project after formal closure (ATB, personal communication, 2020). In the aftermath of the current study, a national cluster randomized controlled trial with a complex intervention of compulsory early integration of palliative care was developed in Norway [9]. An SCP, an education program, and systematic symptom assessment constitute the essentials of the intervention. Looking further into the future, an SCP with integrated decision support may represent a promising approach [37].

Conclusion

A comprehensive SCP, integrating oncology and palliative care across levels of care, was developed and implemented in a rural region of Mid-Norway. The SCP was found to be a feasible approach to improve palliative cancer care, despite different perspectives of care in specialist and community care. With an extensive implementation strategy, improvements were demonstrated for HCLs' and HCPs’ experiences with the quality of cancer care in the region. However, limited use of the SCP in clinical practice was reported. Limitations in knowledge and project involvement regarding the implementation strategy may have restricted the incorporation and clinical use of the SCP. Further research must address what are the most important elements for usefulness and successful implementation of a care pathway for palliative cancer patients in clinical practice.

References

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):394–404.

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–30.

Fulton JJ, LeBlanc TW, Cutson TM, et al. Integrated outpatient palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33(2):123–34.

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):e588–653.

Mesteig M, Helbostad JL, Sletvold O, Røsstad T, Saltvedt I. Unwanted incidents during transition of geriatric patients from hospital to home: a prospective observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):1.

Schrijvers G, van Hoorn A, Huiskes N. The care pathway: concepts and theories: an introduction. Int J Integr Care. 2012;12(Spec Ed Integrated Care Pathways):e192.

Kinsman L, Rotter T, James E, Snow P, Willis J. What is a clinical pathway? Development of a definition to inform the debate. BMC Med. 2010;8:31.

Hjermstad MJ, Aass N, Andersen S, et al. PALLiON - PALLiative care Integrated in ONcology: study protocol for a Norwegian national cluster-randomized control trial with a complex intervention of early integration of palliative care. Trials. 2020;21(1):303.

Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, Machotta A, Steyerberg EW. The quality of the evidence base for clinical pathway effectiveness: room for improvement in the design of evaluation trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:80.

Albreht T, Kiasuwa R, Van den Bulcke M. EUROPEAN Guide on Quality Improvement in Comprehensive Cancer Control (electronic source): Ljubljana: National Institute of Public Health ; Brussels: Scientific Institute of Public Health; 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 24]. Available from: https://cancercontrol.eu/archived/uploads/images/Guide/pdf/CanCon_Guide_FINAL_Web.pdf.

Finn L, Malhotra S. The Development of Pathways in Palliative Medicine: Definition, Models, Cost and Quality Impact. Healthcare (Basel). 2019;7(1).

Collins A, Sundararajan V, Burchell J, et al. Transition points for the routine integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(2):185–94.

Rosstad T, Garasen H, Steinsbekk A, Sletvold O, Grimsmo A. Development of a patient-centred care pathway across healthcare providers: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:121.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795.

Robertson R, Jochelson K. Interventions that change clinician behaviour: mapping the literature National Institute of Clinical Excelence (NICE). 2006:1–37.

Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2013;347:f6753.

Peters DT, N; Adam, T, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization. Implementation research in health: a practical guide: World Health Organization; 2013 [cited 2021 March 18]. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/implementationresearchguide/en/.

Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Jannert M, Kaasa S. A palliative-care intervention and death at home: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9233):888–93.

Morita T, Miyashita M, Yamagishi A, et al. Effects of a programme of interventions on regional comprehensive palliative care for patients with cancer: a mixed-methods study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):638–46.

Brenne AT, Knudsen AK, Raj SX, et al. Fully integrated oncology and palliative care services at a local hospital in mid-norway: development and operation of an innovative care delivery model. Pain Ther. 2020;9(1):297–318.

Rosstad T, Salvesen O, Steinsbekk A, Grimsmo A, Sletvold O, Garasen H. Generic care pathway for elderly patients in need of home care services after discharge from hospital: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):275.

Extend Norway [cited 2020 Oct 15]. http://www.extendnorway.com/about-extend/.

Ewing G, Grande G, National Association for Hospice at H. Development of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for end-of-life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2013;27(3):244–56.

Sartain SA, Stressing S, Prieto J. Patients’ views on the effectiveness of patient-held records: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2666–77.

Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):44–53.

Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–8.

Tjora A. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis, 2. utgave (Norwegian). Oslo, Norway: Gyldendal akademisk; 2012.

Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(8):795–805.

Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, Yennu S, Bruera E. Attrition rates, reasons, and predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1098–105.

St. Olavs Hospital HF. Forbedringsprogram 2013 (Norwegian). 2013 [cited 2017 Dec 12]. https://ekstranett.helse-midt.no/1010/Sakspapirer/41-12%20Vedlegg%202%20Forbedringsprogram%20for%202013.pdf.

Norwegian Government. Veileder til lov 20. juni 2008 nr. 44 om medisinsk og helsefaglig forskning (helseforskningsloven)(Norwegian): Norwegian Government; 2010 [updated March 25, 2010; cited 2021 July 1]. Available from: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/hod/hra/veileder-til-helseforskningsloven.pdf.

Yates JW, Chalmer B, McKegney FP. Evaluation of patients with advanced cancer using the Karnofsky performance status. Cancer. 1980;45(8):2220–4.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–55.

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–9.

Mitchell S, Tan A, Moine S, Dale J, Murray SA. Primary palliative care needs urgent attention. BMJ. 2019;365:l1827.

Lohre ET, Thronaes M, Brunelli C, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. An in-hospital clinical care pathway with integrated decision support for cancer pain management reduced pain intensity and needs for hospital stay. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(2):671–82.

Chan RJ, Webster J, Bowers A. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD008006.

Seys D, Panella M, VanZelm R, et al. Care pathways are complex interventions in complex systems: New European Pathway Association framework. Int J Care Coord. 2019;22(1):5–9.

Evans JM, Mackinnon M, Pereira J, et al. Integrating early palliative care into routine practice for patients with cancer: a mixed methods evaluation of the INTEGRATE Project. Psychooncology. 2019;28(6):1261–8.

Seys D, Deneckere S, Lodewijckx C, et al. Impact of care pathway implementation on interprofessional teamwork: An international cluster randomized controlled trial. J Interprof Care. 2019:1–9.

McAlearney AS, Walker DM, Livaudais-Toman J, Parides M, Bickell NA. Challenges of implementation and implementation research: learning from an intervention study designed to improve tumor registry reporting. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:1–8.

Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(1):54–60.

Tripepi G, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Zoccali C. Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;115(2):c94–9.

Hjermstad MJ, Hamfjord J, Aass N, et al. Using Process Indicators to Monitor Documentation of Patient-Centred Variables in an Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care Pathway-Results from a Cluster Randomized Trial. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9).

de la Cruz M, Reddy A, Vidal M, et al. Impact of a palliative care checklist on clinical documentation. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(2):e241–7.

O’Brien B, Graham MM, Kelly SM. Exploring nurses’ use of the WHO safety checklist in the perioperative setting. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(6):468–76.

Luig T, Asselin J, Sharma AM, Campbell-Scherer DL. Understanding implementation of complex interventions in primary care teams. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):431–44.

Evans-Lacko S, Jarrett M, McCrone P, Thornicroft G. Facilitators and barriers to implementing clinical care pathways. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:182.

Bautista MA, Nurjono M, Lim YW, Dessers E, Vrijhoef HJ. Instruments measuring integrated care: a systematic review of measurement properties. Milbank Q. 2016;94(4):862–917.

Torvik K, Kaasa S, Kirkevold O, et al. Validation of Doloplus-2 among nonverbal nursing home patients–an evaluation of Doloplus-2 in a clinical setting. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:9.

Fayers PM, Hjermstad MJ, Ranhoff AH, et al. Which mini-mental state exam items can be used to screen for delirium and cognitive impairment? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(1):41–50.

Sigurdardottir KR, Kaasa S, Rosland JH, et al. The European association for palliative care basic dataset to describe a palliative care cancer population: results from an international Delphi process. Palliat Med. 2014;28(6):463–73.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–44.

Jordhoy MS, Inger Ringdal G, Helbostad JL, Oldervoll L, Loge JH, Kaasa S. Assessing physical functioning: a systematic review of quality of life measures developed for use in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2007;21(8):673–82.

Ewing G, Brundle C, Payne S, Grande G, National Association for Hospice at H. The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):395–405.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients who participated and all HCPs who contributed to the project. The project was a cooperation between European Palliative Care Research Centre, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim University Hospital St. Olav’s Hospital, and 13 municipalities in the Orkdal region (Orkdal, Skaun, Oppdal, Rennebu, Meldal, Rindal, Surnadal, Halsa, Agdenes, Snillfjord, Hemne, Hitra and Frøya).

Funding

The project was funded by the Norwegian Foundation Dam for Health and Rehabilitation, the Norwegian Cancer Society, the Norwegian Directorate of Health [11/2341–26], and Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association Orkdal. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Anne-Tove Brenne, Erik Torbjørn Løhre, Anne Kari Knudsen, Morten Thronæs, Jo-Åsmund Lund, and Stein Kaasa designed the study. Anne-Tove Brenne, Anne Kari Knudsen, Nina Kongshaug, Marte Nilssen Neverdal, Kristina Rystad, Marianne Haug Johansen, and Tone Inga Braseth recruited participants, collected and analysed the data. Anne-Tove Brenne, Erik Torbjørn Løhre and Anne Kari Knudsen wrote the manuscript. Anne-Tove Brenne and Erik Torbjørn Løhre contributed equally.

Prior Presentation

Preliminary data of this manuscript was presented at 6th International Seminar of the European Palliative Care Research Centre (PRC) and European Palliative Care Research Network (EAPC RN) in Banff, Alberta, Canada on December 1–3, 2016. Parts of the results have earlier been published in: Neverdal, MN and Rystad, K: Collaboration in Healthcare: Establishment of a Standardized Care Pathway Across Specialist and Primary Care. Master thesis NTNU 2014 (http://hdl.handle.net/11250/266788). Braseth, TI: Patient Held Record and Individual Plan; do they support care for patients receiving palliative care? Master thesis NTNU 2016. Johnsen, M: Implementation of a standardized care pathway in palliative cancer care- healthcare professionals experiences. Master thesis NTNU 2016.

Disclosures

Anne-Tove Brenne, Erik Torbjørn Løhre, Anne Kari Knudsen, Morten Thronæs, Jo-Åsmund Lund, Nina Kongshaug, Marte Nilssen Neverdal, Kristina Rystad, Marianne Haug Johansen, Tone Inga Braseth and Stein Kaasa have nothing to disclose. New affiliations: Marte Nilssen Neverdal, MsC, Sopra Steria Trondheim, Powerhouse, Brattørkaia 17, 7010 Trondheim, Norway; E-mail: marteneverdal@gmail.com; Kristina Rystad, MsC, Ernst & Young Trondheim, Havnegata 9, 7010 Trondheim, Norway; E-mail: kristrys@gmail.com.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (2014/212). All participants gave their informed consent before participation. HCLs and HCPs interviewed during the spring of 2014 did not provide written consent, as these interviews were part of a quality assurance project at St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital [31, 32]. The participants signed separate consent forms for the quantitative and qualitative data collection. The study conformed to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013, concerning human and animal rights, and Springer’s policy concerning consent has been followed.

Data Availability

The data analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brenne, AT., Løhre, E.T., Knudsen, A.K. et al. Implementing a Standardized Care Pathway Integrating Oncology, Palliative Care and Community Care in a Rural Region of Mid-Norway. Oncol Ther 9, 671–693 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-021-00176-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-021-00176-y