Abstract

The notion of interculturality is complex and polysemous in global research and education. Considering the turbulent times that the world has experienced in recent years, it is increasingly important to confront and enrich this significant scientific notion to make it more inclusive and epistemologically diverse. This paper has two main objectives. First, it reviews the current state of the global literature on the notion of interculturality in education published in English, observing how different ideologies occupy the field—from dominating voices to ‘minor’ ones which are more glocalized (global + local). On the basis of this review calling for more ‘minor’ voices to be heard, the core of the paper is based on the analysis of discussions between Chinese students at a specific institution of higher education (a ‘minority-serving institution’ or Minzu University) in China, where students from the 56 different Minzu groups of China live, study and cooperate together. The glocal ideology of Minzu (often mistranslated as ‘ethnic’ in English), a form of interculturality, is specific to this context and has not been systematically researched. Three groups of students with different ‘Minzu/ethnic’, linguistic and study profiles were paired together to discuss what interculturality could mean and entail. Three interrelating layers of discourses were identified through a dialogical discourse analysis of what the students co-constructed together: glocality, politics and philosophy of life for all. In general, the students demonstrated a nuanced understanding of interculturality that intersected partly with global academic discourses of interculturality. Their insights contributed advanced reflections and critical thoughts on the notion, highlighting the need for a collaborative and innovative approach to its understanding and utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although the notion of interculturality has been omnipresent in the global educational and academic literature over the past decades, there is still an infinite amount to say about it, especially in turbulent times like ours with wars, economic-political conflicts and generalized polarization (Zembylas, 2023). Since diversity and plurality are the foundations of interculturality, one should rejoice at the apparent multipolarity and polysemy of its ‘geopolitics of thought’ (Mignolo, 2002). However, there are some signs that the global academic system of interculturality as discussed in the English language might be ‘blocked’—see saturated—at the moment, regardless of current calls for decolonizing (R’boul, 2020; R’boul et al., 2023) and interculturalizing interculturality (Dervin, 2021).

This paper has two main objectives. First, it briefly reviews the current state of the global literature on interculturality in education, observing how different ideologies (understood here as ‘orders’ to conceptualize interculturality in certain ways based on e.g. specific economic-political beliefs in different contexts) occupy the field—from dominating voices to ‘minor’ ones which are more glocalized (global + local)—to reflect on the potential complementarity of these perspectives (Dervin, 2023). The core of the paper is based on the analysis of discussions between Chinese students at a specific institution of higher education, a so-called ‘minority-serving institution’ or a Minzu university in China, where students from the different 56 Minzu (‘ethnic’) groups of China live, study and cooperate together. Our interest is in exploring how, by listening to these students, who do not specialize in the notion of interculturality but experience it daily at their institution, we might renegotiate and enrich what the notion of interculturality could be about and entail. The paper is not about judging if the students are right or wrong (or something else) in the way they co-construct interculturality but to contribute to and stimulate further discussions on the notion, especially beyond dominating takes (see Atay & Chen, 2020). We note that the glocal Chinese ideology of Minzu, a form of interculturality which could be reminiscent of other takes on minority/majority in some parts of the world, is specific to this context and has not been systematically researched. Three groups of students from the Chinese minority-serving institution with different ethnic and linguistic profiles were paired together to discuss what interculturality could mean and entail. We ask the following questions: How do the students construct the notion of interculturality? How similar and different might it be from global perspectives? How do they define and suggest ‘doing’ interculturality based on their experiences of living and studying at a ‘minority-serving institution’ in China?

The Notion of Interculturality as a Complex but Dominated Range of Ideologies in Education and Research Globally and in English

In this paper, we deal with interculturality as a notion used in research and education to make sense of and set educational agendas for encounters between e.g. people, knowledge, things, rather than interculturality as a concrete phenomenon whose complexities can be done and understood in highly inter-personal and (often) indescribable ways. This important distinction made by Dervin (2023) reminds us that a scientific notion (interculturality here) may not always correspond to the complex realities experienced by multilingual and (potentially) ideologically divergent individuals. Dervin (2022) has also argued that focusing on the multifaceted ways interculturality is ‘put into words’ multilingually and ideologically can help interculturalists revise, increase epistemological diversity and enrich their takes on the notion.

While intercultural communication education and research may appear to be unpolitical, see depoliticized, or independent from e.g. governments and economic agendas, it is often deeply intertwined with the interests and ideologies of some dominating ‘Western’Footnote 1 countries (Atay, 2019; Servaes & Carpentier, 2012). Therefore, we note that the notion of interculturality cannot escape from ideology (Roucek, 1944) and that it systematically relates to the market and politics. (Dervin & Simpson, 2020). As such, the notion cannot but be embedded in ‘governance’ by economic forces, symbolized by the trio of the powerful, the consumer, the excluded (Augé, 2017). Thus, any assertion, position and construction of interculturality and what it means (or not) and entails (or not) in educational and research contexts relate to these elements. We also argue that there is a danger in not recognizing this important aspect of the scholarship on the notion, pretending that geo-economic-political forces have nothing to do with education and research of interculturality (Atay, 2019).

When one observes publications in English from the broad field of intercultural communication education and research one notes, maybe without any surprise, that the most influential conceptual and theoretical ones are produced by scholars located in the ‘West’ (mostly the UK and US, see Peng et al., 2019; R’boul & Dervin, 2023). These publications tend to disseminate ideological orders and features about interculturality to other systems of thought located in e.g. the Global South, which do not necessarily have the power to resist or to return the favour (R’boul, 2022; Monceri, 2019). This seems to generate a somewhat unipolar order of interculturality in the global production, consumption and dissemination of intercultural knowledge in research and education, especially in the English language. In fact, the dominant voices about the notion of interculturality might ignore or disqualify ‘minor voices’, while, at times, showing signs of sympathy and generosity towards them (Mignolo, 2002; Zembylas, 2023). It is fair to say that the grounds do not appear level in research and education about interculturality. How this status quo is handled and changed is one important question addressed in this paper by giving the floor to unheard voices in the field.

At the moment, for instance, there are clear signs that the ideologies of non-essentialism, non-culturalism, intercultural citizenship and democratic culture, which were put forward and circulated by the ‘West’, dominate the way interculturality is discussed in global research in education (Dervin, 2023; Simpson, 2023). One important point, represented by what could be referred to as ‘dominating figures’ of interculturality, relates to an article published by Peng et al. (2019) where the authors propose a bibliometric analysis of the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research—one central concept and ideology in intercultural communication education and research. What the authors find is that the dominating figures in the literature (1. Byram, 2. Deardorff, 3. Kramsch, 4. Hammer, 5. Bennett) are all white, Anglo-Saxon, English-speaking scholars, based in American and/or British universities. It is important to note that some of these scholars also work with supra-national institutions which promote how interculturality should be defined, done (taught) and evaluated, defining dominating ideologies about the notion, on the basis of ideologemes constructed by the ‘West’ (e.g. intercultural citizenship; democratic culture). This is the case of the first two scholars identified by Peng et al. (2019), Byram and Deardorff, who produce reports, frameworks and even textbooks in the English language for e.g. the Council of Europe, the UNESCO and the OECD, which are used as reference documents around the world.

We note that dialogues might appear between differing minor/major ideologies of interculturality such as multiculturalism and interculturalism (Meer & Moodood, 2012); interculturalidad from South America and ‘western’ interculturality (Guilherme & Menezes de Souza, 2020); interculturality and Minzu (Dervin & Yuan, 2022). Sometimes, overlaps and linkages between these ideological positions are attempted, but, to our knowledge, very few such actions have been successful, either because they are opposed politically (like multiculturalism vs. interculturalism) or the forms of knowledges that are borrowed are stripped of their ‘real’ tunes and/or textures and become at times tokenistic (see Song, 2022; Chemla & Keller, 2017).

The dominance of the field has some clear consequences on the usefulness and relevance of the notion of interculturality. As stated earlier some voices remain unheard and not given the floor in international publications, dominants tend to cocoon together and to promote their own ‘tribes’; minor voices also tend to be looked down upon and lectured about what is ‘right’ interculturality, the ‘right’ way of approaching it (R’boul, 2022; Zembylas, 2023). In recent years, research on interculturality in e.g. language education has been increasingly politicised—while pretending not to be. Concepts and notions such as democratic culture, human rights, citizenship have been introduced in the field by dominant figures, who work with supranational institutions such as the Council of Europe (Porto, 2014). These highly political, but also glocal, notions and concepts are polysemic, and they might turn a ‘localized’ ideology from e.g. Europe into potentially dominant refrains in education and research. They tend to be used as ideological orders as to what and how interculturality should be. Only certain ways of understanding and ‘doing’ them are then put forward as acceptable, thus neglecting the opinion and conceptualizations of the ‘Other’—other ideologies. When these are used by the ‘Other’ in research and education, they can produce what we could call schizophrenic perspectives, whereby opposed politico-economic perspectives might be combined. Finally, the dominants tend to treat interculturality in English as a lingua franca beyond multilingualism i.e. as if the English language was transparent and the connotations of words were the same cross-linguistically (Liu et al., 2021).

Moving forward with both intercultural research and education might thus entail recognizing and accepting that the way we conceptualize, problematize and use the notion of interculturality is (only) one of the ways to engage with it globally. Interculturalizing interculturality was proposed by Dervin (2021) and Dervin and Jacobsson (2022) to discuss the need to expand the notion, enriching the way we think about interculturality, identifying the problems that we face in/directly through confronting our ideologies with other ideologies (as a reminder: the ‘orders’ we have been given about how to research and educate for interculturality). It is not about ‘swallowing’ blindly other influences but about weighing consciously the pros and cons of other ways of engaging with the notion intellectually, emotionally, politically, economically, scientifically, etc. and to decide what to take (or not). More importantly, interculturalizing is about viewing one’s own ideologies from a ‘stranger’ position—to step back and to look into one’s ‘own interculturality’ through the reflection of an other’s interculturality. Interculturalizing is thus also about asking questions, without always providing answers (especially just one answer). Actually, problems of interculturality tend to be somewhat similar around the world (for example, how to treat someone who appears different from/similar to me?) and yet the solutions to these problems will be very different depending on the ideologies one follows, the ways one conceptualizes self, other, the world, difference and similarity, etc. (Dasli & Diaz, 2017; Zembylas, 2023).

Working on the notion of interculturality in education and research might then wish to focus on (see Dervin & R’boul, 2022; R’boul & Dervin, 2023):

-

Realizing that any take on the notion contains ideological positioning, which might lead to misinterpreting and judging others’ positions when interacting with them around it.

-

Giving space to and understanding these other positions to enrich our own ways of dealing with interculturality that are fairer and more inclusive.

-

Languaging around the concepts and notions used to problematize and discuss interculturality in research is necessary since these might mean and/or be connoted differently. Exploring the ways things are said and constructed multilingually has to be part and parcel of interculturality.

In intercultural communication education, reviewing and analysing the different ways interculturality are constructed linguistically and discursively could make students more eager and curious to discover other perspectives while learning to weigh their pros and cons. The ultimate goal could be to help students think about how they wish to ‘do’ interculturality privately and in their professional context by making (changing) informed choices while engaging with others. In what follows, we get to listen to unheard voices in the broad field of intercultural communication education: Chinese students based at a ‘minority-serving institution’ in Mainland China who do not specialize in the notion of interculturality but experience it as a complex phenomenon on a daily basis at their university.

Research Design

Research Purpose and Background

This paper derives from and is embedded in the second author’s long-term and international engagement with how the notion of interculturality can be problematized, diversified and taught in higher education in different parts of the world (amongst others: Canada, China, France, Finland, India, Malaysia, Sweden, see Dervin, 2016, 2022). Our goal with this paper is not to define what interculturality is or what it is not. It is not about giving ‘ideological orders’ (Althusser, 2020) about how it should be ‘done’, especially in the way we meet the ‘Other’. The paper aims to examine how Chinese students at a ‘special’ university (Minzu University of China, Beijing), who do not specialize in interculturality, co-construct the very notion of interculturality, how similar and different it is from global takes on the notion and what it is that we can learn from their takes. University students play a crucial role in knowledge creation and dissemination, which is often disregarded in research. Our aim is to listen to and analyse their views on the notion of interculturality, how they interpret it and their suggestions on its implementation. In the existing literature, it is common for scholars and educators to provide sets of guidelines on how to practice interculturality and what actions are deemed essential for being ‘intercultural’ (Tan et al., 2022). However, in this study, we seek to break away from this pattern and amplify the voices of Chinese students who possess diverse experiences, which are often undocumented and under-explored. By listening to the students, we aim to encourage questioning the idea that interculturality is a universally applicable concept in today’s world.

Let us now say a few words about the notion of Minzu (民族) and about the specific type of minority-serving institution under review. Minzu is a complex yet central notion to Chinese ‘interculturality’ (Dervin, 2022). Systematically mistranslated as ‘ethnic groups’ or ‘nationalities’ in English, Minzu refers to a diverse range of cultural and linguistic groups amongst the Chinese. Throughout its history, the Middle Kingdom (translation of the name of China in Chinese) witnessed interactions between multiple Minzu groups. 56 Minzu group identities and memberships are officially recognized by the Chinese State today. The Han group represents about 91.5% of the population while the other 55 Minzu groups 8.5% (Zang, 2016: 1). Minzu status appears on people’s identity documents and depends on their parents’ own status (such as Chinese Han, Chinese Korean, Chinese Uighur). Different Minzu groups are scattered in different territories of the country, with many concentrated on border regions with e.g. Kazakhstan, Korea, Mongolia and Russia. There are also five provincial-level ethnic autonomous regions such as the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Sude et al., 2020). It is important to bear in mind with Wang and Du (2018: n.p.) that “ethnic minorities [Minzu] are not a group of homogenous people. The differences within ethnic minorities should not be ignored as well”. It is also critical to note that some Minzu groups have different first languages on top of Mandarin Chinese, the common language of Mainland China and that some of their languages were divided politically at some point but might be very similar to other Minzu languages.

Minzu institutions like the one under review here were established in China in the 1940s, now including six Minzu institutions directly affiliated to the Central Ministry of Minzu Affairs and nine institutions managed by local governments at the provincial and autonomous regional levels. These institutions of higher education for Minzu represent a kind of microcosm of China’s multiculturalism (Dervin & Yuan, 2022). They aim to promote local knowledge, Minzu unity and prosperity, improve the overall degree of education for all and balance regional development. Founded in 1941, Minzu University of China (MUC) is an institution located in Beijing, with a focus on multidisciplinary research on Minzu. At the university, members of all Minzu groups, coming from all over the country, study, work and live together in multidisciplinary schools ranging from linguistics to traditional medical studies. MUC is one of the 38 key Chinese universities and has a teaching faculty of about 2,000 members for 14,000 students. About two third of the students are Minzu ‘minority’ students. In this paper, it is not our interest to evaluate how successful Chinese ‘minority-serving institutions’ are (see e.g. Ye et al., 2023) but to focus on how students from such institutions engage with the notion of interculturality as potential examples of interculturalizing interculturality.

Methodology

The 21 participants for this study were selected from MUC School of Education (year three bachelor’s general program). None of the students had had any course on or any background in interculturality/intercultural communication education research. They were divided into seven discussion groups, with each group consisting of three students. The composition of the groups is intentionally diverse, incorporating students from three different Minzu groups (Han, Qiang and Uyghur) and regions of China to ensure varied representation (see Table 1).

During the study, the participants were tasked with engaging in discussions related to their understanding of interculturality. Three carefully phrased questions in Chinese were provided to them on paper as prompts: How do you understand the notion of interculturality? How does it relate to your experiences at MUC? Do you have any advice as to how to do interculturality? The translation of the very word interculturality from English into Chinese required discussions between us since different words could refer to the notion in Chinese. We decided to use the word 跨文化 (kuà wénhuà), bearing in mind that the root 跨 could be translated as cross-, see trans- in English. We accept that this might influence the students in their co-construction of the notion.

Each group discussion lasted for about one hour and a half. The students worked by themselves with their peers while the researchers assumed the role of observers during data collection, keenly documenting the dynamics, interactions and content of the group discussions without actively participating or exerting any influence on the conversation. We argue that this method, close to focus groups (see Markova et al., 2007), creates a space for students to engage in open and independent discussions on interculturality, facilitating a potentially more comprehensive exploration of the subject matter. The data were collected in Chinese, transcribed and then translated into English by the authors, applying a joint critical and reflexive approach to data translation (see Dervin, 2023).

In the following analysis, we make use of a qualitative research method called dialogical discourse analysis, a strong method that has been used by the second author for two decades to decipher discourses on the notion of interculturality in multiple languages and contexts (Markova et al., 2007; Angermuller, 2014; Dervin, 2016). Based on Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s dialogism (e.g. Bakhtin, 1984), a theoretical framework that examines the ways in which language is used in various contexts and the meanings/connotations it produces, this analytical perspective helps us emphasize the significance of dialogue and interaction in shaping research participants’ understanding and co-construction of (here) interculturality. Bakhtin’s dialogism posits that language is inherently dialogic, shaped by multiple voices and perspectives (Bakhtin, 1984). During the discussion groups, we consider that our participants thus engage in ongoing conversations with others, both real and imagined, which influence their language use and thus the way they discuss the notion of interculturality. When concretely applied to analyse what people say, dialogical discourse analysis attempts to uncover the underlying meanings/connotations, power dynamics and ideologies that are present within language (Markova et al., 2007). This type of analysis involves examining both the linguistic features of what people say (e.g. use of particular pronouns, evaluative terms, modals), as well as the broader social and historical context in which the communication occurs (here: Chinese ‘Minzu’). By doing so, we aim to comprehend e.g. the hidden and social ideologies as well as shifts and potential contradictions present in the participants’ discourses about interculturality (see Dervin, 2023). It is important to note that while the students’ experiences and discourses of interculturality cannot be generalized to the entirety of MUC or even ‘China’, we argue that they offer valuable insights that can broaden our understanding of interculturality and reveal potential similarities and differences with approaches in other (dominating) contexts.

Analysis

Based on the dialogical discourse analysis of the seven group discussions, the following elements were identified in the data: discourses about the institution as a place of (‘Chinese’) interculturality (3.1) and interculturality as glocality, politics and philosophy of life for all (3.2.). Because of space limitation, a total of 14 excerpts were carefully selected as being representative of the students’ diverse voices.

MUC as a Place of (‘Chinese’) Interculturality

As stated before, the participants did not specialize in interculturality and had never taken any courses on the notion. We start the analysis by looking into how they seem to describe systematically their experiences at MUC through what could be described as typical intercultural terms—although the term intercultural is not systematically used by the participants in Chinese to do so. It is important to highlight that starting from year 1 of their undergraduate studies, MUC students, who come from various regions and belong to different Minzu groups, encounter a campus environment that they describe as ‘superdiverse’. To gain insights into the participants’ campus experience and how this might indicate their takes on the notion of interculturality, we listen to their own accounts of daily interactions with others in what follows.

Excerpt 1 represents typically how the students first discuss differences that they have observed in terms of (regional) habits, preferences and language use on campus between themselves and others before evaluating the kind of learning opportunities that these represent:

Excerpt 1

Upon enrolling at Minzu University, I noticed that students hailed from diverse regions and belonged to various Minzu groups, each with their own unique cultural backgrounds and influences they had acquired since childhood. It became evident that certain aspects that seemed commonplace to some were not easily comprehensible to others. For instance, students from northeast China might refer to a tomato using a different name, leading to communication obstacles. Similarly, students from the southern regions initially expressed their discomfort with the university public bathhouse, which they were unfamiliar with. However, through effective communication, a sense of understanding and respect for each other’s cultures gradually emerged among all the students (Li (NB: all names are pseudonyms), group 1).

Interestingly in the students’ utterances about MUC as a place of (‘Chinese’) interculturality, similar patterns in the construction of their discourses appear. As such, at the end of excerpt 1, Li inserts some type of coda (a kind of conclusion offering a ‘moral’ or a ‘piece of advice’, see De Fina & Johnstone, 2015) to evaluate what the interculturality as difference described in the excerpt brings to the students: ‘a sense of understanding and respect for each other’s cultures’, accompanied by a generic formulation that includes ‘all the students’ at MUC. Xiu from group 5 and Hao from group 7 operate very similar discursive strategies, while focusing on an in-group voice (‘we’ in Xiu) and a more personal one (‘I’ in Hao):

Excerpt 2

By taking the time to explore and appreciate these treasures [cultural differences], we can expand our knowledge and understanding of different cultures. As a result, we will develop a more inclusive mindset, fostering a conducive environment for meaningful intercultural exchange to thrive. (Xiu, group 5)

Excerpt 3

Surrounded by a diverse community of students, including many from minority backgrounds, I have become intimately acquainted with the concept of Minzu diversity. This exposure has enabled me to develop a deeper understanding of both the similarities and differences between various Minzu groups, fostering a sense of familiarity and respect for one another. (Hao, group 7)

For Xiu, interculturality at MUC leads to ‘developing a more inclusive mindset’ while, for Hao, ‘develop(ing) a deeper understanding of both the similarities and differences between various ethnic groups, fostering a sense of familiarity and respect for one another’. One finds in excerpts 1–3, what could be labelled as very typical discourses of interculturality as have been identified in the international literature (e.g. Byram, 1997). There thus seems to be intertextuality and dialogism (Markova et al., 2007) in the ways interactions between representatives of different Minzu groups and e.g. international–intercultural encounters are described here.

What seems to differ from global takes on the notion includes the ways the diversity of other students is formulated and discoursed in Chinese. For example, when De talks about important events at MUC, he uses many positive evaluative devices (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2008) when he refers to others’ ‘cultural’ practices:

Excerpt 4

Every gathering or celebration at Minda University is akin to a vibrant and enriching multicultural feast. Our university takes great pride in commemorating festivals from various Minzu groups. For instance, we joyously partake in the Dai’s exhilarating Water Splashing Festival and the Yi's mesmerizing Torch Festival [NB: Dai and Yi are Minzu ‘Minorities’ respectively]. These festive occasions offer us a remarkable opportunity to delve into the essence and splendor of diverse Minzu cultures. As we immerse ourselves in these festivities, we gain a profound appreciation for the unique traditions, customs, and historical significance that each Minzu group brings forth. It is through these celebrations that we witness the depth and beauty that lies within the tapestry of intercultural diversity. (De, group 5)

The list of positive evaluatives in Excerpt 4 seems to serve the purposes of both praising the ‘other’ while determining the students’ attitudes towards this diversity (in alphabetical order): depth and beauty, enriching, (taking) great pride in, joyously partake in, mesmerizing, profound appreciation, a remarkable opportunity, splendor of diverse Minzu cultures, vibrant. Based on our knowledge of the institution’s own discourse on Minzu diversity and official takes on the ideology of ‘unity in diversity’, central to Minzu in Mainland China, one could hear the influence of such voices on De’s description of MUC interculturality (Wang & Du, 2018; Dervin & Yuan, 2022).

Glocality, Politics and Philosophy of Life for All: Students’ Entries into the Notion

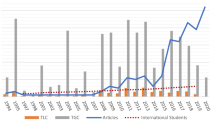

The previous analytical section focused on how discoursing on the specific characteristics of MUC reveals similar and specific takes on the notion of interculturality. In what follows, through the analysis of the students’ collective reflections in their discussions, it becomes evident that their perspectives on the notion interculturality itself are multifaceted. As such, they often incorporate and blend in specific ideologies, while also presenting contradictions and engaging in critical questioning. As shown in Fig. 1, for the students, interculturality represents three different layers of discourses: Glocality, politics and philosophy of life for all.

Glocality (global + local) has to do with how, as a complex notion, interculturality should always be considered under the lenses of both the international and the local in research and education. Through their experiences at MUC, the students seem well able to problematize these different influences on how they perceive the notion. As far as politics is concerned, many of the students discuss the influences of interculturality on self and other, for example when political decisions are made towards specific cultures (Cheng, 2004). Interestingly, the students are also very much aware of the issue of ‘knowledge colonization’ and discuss politics of knowledge, calling for individuals to move beyond e.g. Eurocentric positions on interculturality. To our knowledge, this kind of positioning amongst Chinese students in intercultural communication education has not been systematically noted before (see exceptions in Song, 2022; Xu, 2022). The last aspect of the triangle is entitled interculturality as a philosophy of life for all and has to do with the ways the students reflect on what interculturality means and entails beyond the economic-political, focusing on everyday aspects. This includes accepting the omnipresence of interculturality and questioning the problematic divide between intercultural and the rest, the need for individuals to treat the way they ‘do’ the notion together in equal and innovative ways and, finally, to develop specific skills to use interculturality as a tool for understanding the world.

Interculturality as Glocality

In their discussions, most of the students discuss the dialectics of global versus local interculturality—an aspect that is most certainly influenced by the very special context of Minzu University. In the following excerpts, the students are very clear about this dichotomy, referring to their experiences at e.g. the university dormitories (references to different languages and living habits):

Excerpt 5

I mainly think there are two kinds of interculturality: global interculturality and local interculturality. For example, the people in our dormitory are from different regions, including Sichuan, Xuzhou, Shandong, Hebei, Hunan and Hubei, and what we talk about is the different food and eating habits of each place, which is also a kind of intercultural exchange, but this is local interculturality. (Ai, group 3)

Excerpt 6

Here are some examples from our dormitory: there are a total of eight people in our dormitory, and I am the only one from the north, so my feelings are quite obvious. There are some differences in living habits, eating habits, and lifestyles between me and other students from the South; on the other hand, there are also some differences in intonation between their dialects and ours. I feel that their southern dialects (my roommates are mostly from the southwestern region) have some similarities, for example, they may not understand my dialect, and sometimes I can’t understand what they are speaking in dialects. (Ya, group 4)

Here again, the local corresponds to interculturality, whereby differences need to be negotiated amongst people who share the same nationality.

One student even goes as far as recounting two ‘difficult’ events that she experienced at the university to illustrate the dichotomy of local and international interculturality, with the first one concerning ‘local’ interculturality with other Minzu students, and the second about the ‘international level’ (with an Afro-American student). By introducing these two narratives, Fang wishes to make the point that intercultural experiences are not always ‘pleasant’, thus moving away from ideolizing the notion.

Excerpt 7

As I am a Manzu [a Minzu group from Northeast China], we have no taboos and eating pork is quite normal. Once I was in a room, I went in with pork intestines. In fact, I thought it was OK to eat pork intestines, just because there were Kazakh students in the room. One of my classmates’ reaction made me realize that he cannot accept this. He said: “why do you eat intestines? is it not the same as the taste of excrement?” He didn’t eat it himself, but his cultural influence made him think he couldn’t eat pork, he couldn’t eat pork sausage, he thought it was dirty. In fact, I did not want to eat pork in front of them, I was very careful, but I did not know he was in the room, but then I thought I have to change my attitude in the future. As a person without taboos, I am willing to understand and respect their habits. But at that time, if he asked me to leave the room and eat outside, it would have been OK, but he used sarcasm, which was to use his own culture to deny another person’s living habits. I thought this was inappropriate, which was a very unpleasant intercultural experience. (Fang, group 5)

In Excerpt 7, Fang re-enacts a dialogue she had with a student who shares her dormitory, about what she refers to as the ‘taboo’ of eating pork. The other student who was a Muslim used black humour to make her understand that eating pork is ‘problematic’ to her. This makes Fang feels uncomfortable and evaluate the situation as ‘inappropriate’ and ‘a very unpleasant intercultural experience’.

Fang’s second anecdote concerns her interaction with a Black student from the USA who was studying at MUC:

Excerpt 8

And then the second one is with an international student of our school, which is also interesting, he is an international student from the United States, a Black man. In fact, we have seen a lot of bad comments about black students looking for Chinese girlfriends on the Internet. Therefore, I would pay more attention to getting along with this student. However, my own personality makes me willing to make friends. However, in the process of getting along with the Black student, I found that his way of communicating was really different from ours. He would act very close. But I don’t think we knew each other that well. For example, after we had dinner together, he invited me to watch a movie in his dormitory, which is in the international student’s apartment, where other people can go. I thought it was intimate to go to someone’s room and watch a movie, so I said no. I said next time, but I was so surprised that the student directly deleted me on WeChat [a Chinese social media application]. I didn’t understand why, I just wondered whether he had some purpose, when I wasn’t up to his wishes, he directly deleted me. I am very confused. Then I added his WeChat again, and I tried to figure out what was going on. And then the Black student told me that he felt that he was being belittled, that I was rejecting him because he was black. Therefore, what this experience gives me is that when we look at the same problem from different perspectives, we actually have different feelings. If we can’t think about what the other party thinks on the basis of the other party’s culture, there may cause great misunderstanding (Fang, group 5)

This excerpt appears to be formulated candidly, with Fang admitting to her biases towards a Black student and analysing a misunderstanding she experienced with the international student. In the excerpt, Fang navigates between different positions. The first-person pronoun seems to be used to tell the story proper while the generic form of the third-person pronoun (as in: “we have seen a lot of bad comments about black students looking for Chinese girlfriends on the Internet” and in the learning coda of the excerpt) appears to generalize about a group of undefined people with whom Fang seems to identify (Chinese students? Individuals involved in intercultural encounters? See Kerbrat-Orecchioni, 2008). Unlike Excerpt 7, the narrative is not evaluated negatively in the coda but it seems to serve as a ‘collective lesson’ (‘when we look at the same problem from different perspectives, we actually have different feelings’) to deal with interculturality in better ways. Although the two narratives concern different individuals—one from the same country, but from different Minzu groups—and one from the USA, both appear to be intercultural in the sense that the student’s attitude and/or behaviour has led to strong reactions from her interlocutors. At the same time, these events appear to have led her to rethink her engagement with them—although, in the Minzu case, she seems to find it difficult to accept the other’s reaction.

Interculturality as Politics

Interestingly, while in global research the idea that the notion of interculturality is (also) political is not widespread (most scholars still focus on the broad and polysemic concept of ‘culture’, see Holliday, 2011), our participants do not seem to shy away from stating the politicality of the notion. In the data, the aspect of interculturality as politics seems to revolve around the topics of influencing others, making political decisions towards other cultures and the politics of knowledge (beyond Eurocentrism).

By allowing people to see and understand the world in certain ways, many students claim that interculturality can lead to ideological domination. In Excerpt 9, Cheng attempts to illustrate her point with an example from the film industry that she finds interesting:

Excerpt 9

When different cultures interact and influence each other, it leads to the creation of new cultural forms. In the context of American fiction movies entering the Chinese market, it indeed had an impact on the development of Chinese fiction movies. Chinese filmmakers were exposed to different storytelling techniques, visuals, and narrative styles from the West, which influenced their work. During the development of Chinese fiction movies, elements from both Eastern and Western cultures were incorporated. This blending of cultural elements allowed for the creation of a unique style that reflects both Chinese traditions and Western influences. However, the Western influence might also limit the Chinese fiction movies within a certain framework or structure. (Cheng, group 7)

The topic of power imbalance in interculturality has been increasingly discussed in intercultural research over the past decade (e.g. Dai, 2023; Tian & Dervin, 2023). In this excerpt, Cheng engages with the example of the power and influence of American fiction movies in the Chinese market, impacting Chinese filmmakers positively. For Cheng, knowledge transfer through Western films can also equip Chinese filmmakers with new techniques and skills. The power interplay allows for resistance as Chinese filmmakers find their own ways of expression and incorporate Chinese elements. Politics here has to do with balancing influence and creativity interculturally.

In Excerpt 10, Guo includes politics in a list of macro aspects that influence what we do and the way we identify:

Excerpt 10

Intercultural communication exists in politics, economy, diplomacy and every aspect of daily life. Even the communication between any two people is intercultural, because it is very likely that they have different class cultures, different family cultures, different knowledge structures and so on, which will cause people to communicate interculturally. (Guo, group 1)

After listing important macro-contexts, politics included and considering the intersection of multiple identities (e.g. Collins, 2019), Guo maintains that interculturality cannot but affect everyone.

Some other students comment on the fact that interculturality (and (maybe) a lack of it) can be constructed as a ‘strong’ political tool. In the following excerpt, Xiu discusses with two other students a decision that they claim had been made by the Chinese authorities concerning Korean culture:

Excerpt 11

Xiu: I have one more small question. Although intercultural exchanges are now promoted in our country, why does our country still have policies that restrict the import of other countries’ cultures, such as the restriction on Korea?

De: I don’t think it’s a question of interculturality, it’s a political question, because actually we can still go abroad or come into contact with the culture of those countries, it’s not a completely restricted state.

Yang: I remember that the restriction on Korea was mainly issued because there were advertisements in Korea that blatantly insulted our Great Wall, which I think is understandable. (Group 5)

For these students, it is not interculturality that is to be blamed for e.g. blocking access to other cultures and imposing restrictions (probably cultural productions here such as Korean films and music) but politics. The discussed retaliations to ‘insults’ to China (see ‘our great Wall’) against Korea serve as an illustration of interculturality as politics (see Lee, 2019).

Interestingly, for another group of students, interculturality refers to the politics of knowledge production and dissemination (Lawless & Chen, 2021). Chun recounts a discussion he had with a roommate about his own field and how this field is somewhat ‘directed’ by knowledge from the ‘West’. The end of this excerpt asks very original questions as far as this kind of interculturality is concerned:

Excerpt 12

This is a discussion between me and my dormitory roommate not long ago: When multiple different cultures meet, they will sometimes merge and sometimes cause huge contradictions. What is the reason? Is the culture we are now accepting more of a natural development or more of artificial guidance? For example, several of us are studying different subjects, but the classification of modern subjects and the theoretical basis of many subjects all come from Europe. Does our current culture also reflect European culture to a certain extent? With the theoretical foundation of a discipline coming from the outside world, how can our culture achieve cultural self-reliance and build cultural self-confidence? (Chun, group 6)

The excerpt falls into the increasingly popular category of postcolonial critique in interculturality (e.g. R’boul, 2020, 2022; Zembylas, 2023). As such, if we summarize the list of questions posed by Chun in the excerpt, we could formulate them as: When our academic knowledge is so much influenced by the ‘West’ (synonymous with Europe in the excerpt), how can we become more independent theoretically and culturally?

Interculturality as a Philosophy of Life for All

The final aspect of interculturality discussed by the students is labelled here as ‘a philosophy of life for all’. This has to do with the fact that, in the data, most students argue that interculturality is in everything and touches everyone, that it can lead to e.g. innovation, co-construction in daily life for all and that interculturality can serve as a tool/means to understand our shared world.

Let us begin by listening to a student who raises an important argument regarding interculturality while offering a cautionary insight. This perspective serves as a valuable reminder of the complexities associated with intercultural interactions and highlights potential challenges that may arise in navigating diverse contexts (Holliday, 2011):

Excerpt 13

I find interculturality to be quite complex. It encompasses numerous fields, making it challenging for me to come up with its definition. However, I believe it would be fitting to approach interculturality from a philosophical perspective. To me, interculturality is more than just a concept. It serves as a comprehensive means or tool that individuals employ to gain a deeper understanding of the world around them. It enables people to navigate diverse cultural landscapes, fostering mutual respect, empathy, and the exchange of ideas. (Hao, group 7)

In this viewpoint, interculturality is acknowledged as a phenomenon, beyond a ‘mere’ concept, that cannot be easily defined due to its complexity and multidisciplinarity. In the discussion, the student proposes approaching interculturality from a philosophical standpoint, highlighting its practical significance in understanding and making sense of our shared world. Hao views interculturality as a holistic tool that individuals use to navigate diverse cultural contexts, promoting some of the elements usually found in the global literature such as mutual respect, empathy, and the exchange of ideas. Overall, Hao underscores the importance and (maybe) the universality of interculturality as a means of fostering understanding and harmonious interactions between individuals. The fact that she uses the present tense to describe interculturality seems to add to its claimed universality.

Beyond the usual dichotomy of local and international (see 3.2.1.), some students go as far as claiming that interculturality is omnipresent, occurring in and influencing every single individual. This is the case of Ya in Excerpt 14:

Excerpt 14

Interculturality exists in every aspect, in every corner of the world. Every act of communication may be intercultural. So we can learn interculturality in our daily life, or in every communication with friends, families, or colleagues. (Ya, group 4)

The way Ya formulates her thoughts here, by integrating a generic third-person pronoun to express them, seems to aim to convince us of the universality of interculturality.

Interculturality as a philosophy of life for all seems to represent a simple take on interculturality that brings us back to the core of who we are as human beings. For some of the students, interculturality seems to correspond to a contemporary Chinese ideologeme, A community with a shared future for mankind (每日一词∣人类命运共同体, see Staiano, 2023).

Discussion and Conclusion

Based on the second author’s long-term engagement with the notion of interculturality in research and education in different languages and contexts, this paper aimed to problematize interculturality by looking into how it could be ‘interculturalized’ by listening to voices of students with no prior theoretical and conceptual knowledge about interculturality, from a context which has been under-researched—a ‘minority-serving institution’ in China. We opened the paper by reviewing the current domination and limitations of the global field of intercultural communication education and research available in the English language, asking for more epistemological and multilingual diversity to be included in the way the notion of interculturality is expressed, constructed and used. The following research questions were asked: How do the students construct the notion of interculturality? How similar and different might it be from global perspectives? How do they define and suggest ‘doing’ interculturality based on their experiences of living and studying at a ‘minority-serving institution’ in China?

When the students described their observations of and experiences of a Minzu university in Beijing, they showcased its specificities and often focused on the differences between MUC students. These differences were positively evaluated, often reminding us dialogically of official discourses and takes on e.g. the ‘beauty’ of the different Minzu groups and of the ideology of ‘unity in diversity’ (see Yuan et al., 2022). What these differences teach the students was often formulated in very similar terms as in the global literature on interculturality (respect, mutual understanding…). Since the students did not engage in interrogating the potential polysemy of such terms in Chinese and other languages (see Liu et al., 2021), it was impossible to determine what these meant for them. This aspect of interculturalizing interculturality would deserve our full attention to enrich takes on the notion of interculturality further.

Three interrelating layers of discourses were also identified in the data through the dialogical discourse analysis of what the students co-constructed together (Markova et al., 2007): glocality, politics and philosophy of life for all. In general, the students seemed to have demonstrated a nuanced understanding of interculturality. In opening up these three aspects of how the students perceive and construct the notion of interculturality, we noticed that the students did not always refer to idealistic perspectives. For example, some students shared ‘unpleasant intercultural experiences’ from MUC with both local and international students, reminding us of the difficulties one might face in ‘doing’ interculturality. Other students insisted on the politics behind interculturality, referring for example to international ‘clashes’ between China and Korea, having led to bans on Korean ‘cultural imports’ in China. Some students also demonstrated that they were aware of the potential ideologization of interculturality and of the limitations imposed on e.g. knowledge production and dissemination (see Xu, 2022). Finally, many students wished to expand understandings of interculturality beyond the dichotomy of the local/global, by claiming that interculturality is in fact the essence of everything and everyone. References to the intersectionality of identities in people served as a powerful argument to support this argument (Collins, 2019). While we noted some interesting overlaps with dominating takes on the notion of interculturality globally in what the students maintained about it, some elements such as the need to consider interculturality beyond the inter-national were somewhat unique and might have to do with the specific Minzu context represented by their institution (see Dervin & Yuan, 2022).

This is to our knowledge one of the first papers to consider the topic of interculturality with Chinese students while focusing on metadiscourses of interculturality rather than on the notion as a phenomenon that one experiences (see contrasting perspectives in Borghetti & Qin, 2022; Holmes et al., 2022). Although most research on minority-serving institutions from China published internationally tend to use incompatible ‘scientific’ constructs (e.g. the ideologeme of ‘culturally responsive’ derived directly from ‘American’ multicultural education) to look into such institutions—which often leads to overly negative results (Yang, 2017)—our paper represents an attempt to listen to students’ complex takes on the polysemous and complex notion of interculturality rather than ‘judging’ them and their institutions for what they say and do.

Through our analysis of what the students had to say about the thorny, polysemous and highly ideological notion of interculturality we realized that students from this specific university had a lot to say about interculturality and that their complex takes on the notion show what we could qualify as advanced reflections and critical thoughts on it, highlighting the need for a inclusive, collaborative and innovative approach to its understanding and utilization. This is only a case study and in future studies it would be interesting to confront these students from a Chinese Minzu institution with students from another mainstream Chinese university about the notion of interculturality in order to observe how they engage similarly and differently around it. A more long-term perspective (upon graduation and beyond) whereby one would analyse how the students fare, for example, abroad would also be of major interest (Kirshner & Kamberelis, 2021; Moloney, 2023).

Notes

In the paper, we use the words ‘West’ and ‘Western’ between inverted comas to hint at their generalizing and somewhat imaginary nature and to discuss how the notion of interculturality is dominated in global research by scholars located in the ‘West’, who produce publications in the English language in e.g. top international journals. Our intention is not to oppose the ‘West’ to the ‘East’ (and vice versa) in this paper but to problematize imbalanced epistemic power relations in academia. By giving a voice to Chinese students from a specific kind of institution, we hope to contribute to giving hope to those who feel voiceless in the broad field of intercultural communication education.

References

Althusser, L. (2020). On ideology. Verso.

Angermuller, J. (2014). Poststructuralist discourse analysis. Palgrave MacMillan.

Atay, A. (2019). The discourse of special populations: Critical intercultural communication pedagogy and practice. Routledge.

Atay, A., & Chen, Y.-W. (Eds.). (2020). Postcolonial turn and geopolitical uncertainty: Transnational critical intercultural communication pedagogy. Lexington Books.

Augé, M. (2017). The future. Verso.

Bakhtin, M. (1984). The Bakhtin Reader: Selected Writings of Bakhtin, Medvedev, & Voloshinov. (E. Liapunov & M. Holquist, Eds.; A. Morson & C. Emerson, Trans.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Borghetti, C., & Qin, X. (2022). Resources for intercultural learning in a non-essentialist perspective: An investigation of student and teacher perceptions in Chinese universities. Language and Intercultural Communication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2022.2105344

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

Chemla, K., & Fox Keller, E. (2017). Cultures without culturalism: The making of scientific knowledge. Duke University Press.

Cheng, A. (2004). Can China think? Seuil.

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press.

Dai, X. (2023). The development of intercultural communication theories in China. In J. Henze, S. J. Kulich, & Z. Wang (Eds.), Deutsch-Chinesische Perspektiven interkultureller Kommunikation und Kompetenz (pp. 35–57). Springer.

Dasli, M., & Díaz, A. R. (Eds.). (2017). The critical turn in language and intercultural communication pedagogy: Theory, research and practice. Routledge.

De Fina, A., & Johnstone, B. (2015). Discourse analysis and narrative. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis 2 (pp. 152–167). Wiley.

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education. London: Palgrave.

Dervin, F., & Simpson, A. (2020). Interculturality and the political within education. London: Routledge.

Dervin, F. (2021). Critical and reflexive languaging in the construction of interculturality as an object of research and practice (19 April 2021). University of Copenhagen.

Dervin, F. (2022). Interculturality in fragments: A reflexive approach. Springer.

Dervin, F. (2023). Communicating around Interculturality in Education and Research. Routledge.

Dervin, F., & Jacobsson, A. (2022). Intercultural communication education. Broken realities and rebellious dreams. Springer.

Dervin, F., & R’boul, H. (2022). Through the looking-glass of Interculturality: Autocritiques. Springer.

Dervin, F., & Yuan, M. (2022). Revitalizing interculturality in education. Routledge.

Guilherme, M., & Menezes de Souza, L. M. T. (Eds.). (2020). Glocal languages and critical intercultural awareness: The south answers back. Routledge.

Holliday, A. (2011). Intercultural communication and ideology. Sage.

Holmes, P., Ganassin, S., & Song, L. (2022). Reflections on the co-construction of an interpretive approach to interculturality for higher education in China. Language and Intercultural Communication, 22(5), 503–518.

Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (2008). L’énonciation: De la subjectivité dans le langage. Armand Colin.

Kirshner, J., & Kamberelis, G. (2021). Decolonizing transcultural teacher education through participatory action research: Dialogue, culture, and identity. Routledge.

Lawless, B., & Chen, Y.-W. (2021). Teaching social justice: Critical tools for the intercultural communication classroom. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Liu, F., Han, D., House, J., & Kadar, D. Z. (2021). The expressions “(M)minzu-zhuyi” and “Nationalism”: A contrastive pragmatic analysis. Journal of Pragmatics, 174, 168–178.

Markova, I., Linell, P., Grossen, M., & Orvig, A. (2007). Dialogue in focus groups: Exploring socially shared knowledge. Equinox.

Meer, N., & Modood, T. (2012). How does interculturalism contrast with multiculturalism? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33, 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2011.618266

Mignolo, W. (2002). The geopolitics of knowledge and the colonial difference. South Atlantic Quarterly, 101(1), 56–96.

Moloney, R. (2023). Teaching interculturality: Changes in perspective (A story of change). In F. Dervin, M. Yuan, & Sude (Eds.), Teaching interculturality ‘Otherwise.’ London: Routledge.

Monceri, F. (2019). Beyond universality: Rethinking transculturality and the transcultural self. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 14(1), 78–91.

Peng, R.-Z., Zhu, C., & Wu, W.-P. (2019). Visualizing the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research: A bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 74, 58–68.

Porto, M. (2014). Intercultural citizenship education in an EFL online project in Argentina. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14, 245–261.

R’boul, H. (2020). Postcolonial interventions in intercultural communication knowledge: Meta-intercultural ontologies, decolonial knowledges and epistemological polylogue. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 15(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2020.1829676

R’boul, H. (2022). Epistemological plurality in intercultural communication knowledge. Journal of Multicultural Discourses. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2022.2069784

R’boul, H., Barnawi, O. Z., & Saidi, B. (2023). Islamic ethics as alternative epistemology in intercultural education: Educators’ situated knowledges. British Journal of Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2023.2254373

Roucek, J. S. (1944). A history of the concept of ideology. Journal of the History of Ideas, 5(4), 479–488.

Servaes, J., & Carpentier, N. (Eds.). (2012). Participatory communication for social change. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Simpson, A. (2023). Reconfiguring Intercultural Communication Education through the dialogical relationship of Istina (Truth) and Pravda (Truth in Justice). Educational Philosophy and Theory, 55(4), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2022.2098109

Song, Y. (2022). Does Chinese philosophy count as philosophy?: decolonial awareness and practices in international English medium instruction programs. Higher Education, 85, 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00842-8

Staiano, M. F. (2023). Chinese law and its international projection: Building a community with a shared future for mankind. Springer.

Tan, H., Ke, Z., & Dervin, F. (2022). Experiences of and preparedness for Intercultural Teacherhood in Higher Education: Non-specialist English teachers’ positioning, agency and sense of legitimacy in China. Language and Intercultural Communication, 22(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2021.1988631

Tian, X., & Dervin, F. (2023). Power relations and change in intercultural communication education: Zhongyong as a complementary analytical framework. Language and Intercultural Communication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2023.2256310

Wang, W., & Du, L. (2018). Education of ethnic minorities in China. In M. A. Peters (Ed.). Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory (pp. 1–6). Springer.

Xu, X. (2022). Epistemic diversity and cross-cultural comparative research: Ontology, challenges, and outcomes. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1932438

Yang, M. (2017). Learning to Be Tibetan: The Construction of Ethnic Identity at Minzu University of China. London: Lexington Books.

Ye, J.-H., Zhang, M., Yang, X., & Wang, M. (2023). The relation between intergroup contact and subjective well-being among college students at Minzu universities: The moderating role of social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043408

Yuan, M., & Dervin, F. (2020). An introduction to ethnic minority education in China: Policies and practices. Springer.

Yuan, M., Dervin, F., Sude, B., & Chen, N. (2022). Change and exchange in global education: Learning with Chinese stories of interculturality (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Zang, X. (Ed.). (2016). Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China. London: Elgar.

Zembylas, M. (2023). A decolonial critique of ‘diversity’: Theoretical and methodological implications for meta-intercultural education. Intercultural Education, 34(2), 118–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2023.2177622

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Helsinki (including Helsinki University Central Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any interest conflict.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, M., Dervin, F., Mi, J. et al. Negotiating the Complexities and Polysemy of the Notion of Interculturality in Higher Education: Views from Students at a Minority-Serving Institution. Asia-Pacific Edu Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-024-00834-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-024-00834-5