Abstract

The shift to emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19 brought diverse psychological, emotional, and academic challenges for second language (L2) learners. Overcoming these challenges necessitated the utilization of grit, a personality trait signifying perseverance and passion to sustain academic progress. While grit and emotions have been explored in English language learning, their interaction remains underexplored in other languages. Despite Mandarin Chinese being widely learned globally, little previous work has been done to investigate learners’ psychological experiences, the function of L2 grit, and the relationship between them in online learning from the perspective of positive psychology. This might lead to an incomplete understanding of this pattern across domains and contexts, thus impeding the development of this discipline. This study uses a structural equation model to analyze the relationship between L2 grit, anxiety, boredom, and enjoyment based on 204 valid responses from Chinese as a Second Language learners in mainland China. Results underscore the importance of one facet of L2 grit, perseverance of effort in online Chinese language learning, and highlight the domain-specific nature of emotions. It also suggests that educators need not be overly concerned about negative emotions in online education, as they can be overridden by positive emotions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been widely acknowledged that non-cognitive factors, such as grit (personality strength) and emotion, play a significant role in second language (L2) learning (Dewaele et al., 2023a, 2023b; Sudina & Plonsky, 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Grit, defined as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals” (Duckworth et al., 2007, p. 1087), is believed to be an important factor that enables learners to overcome challenges in the long-term goal-oriented L2 learning. The surge of recent research on grit has promoted a new research agenda in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research, particularly among the growing number of studies on emotions. It is, therefore, vital to examine the interplay of grit and frequently experienced emotions across specific domains and contexts (Khajavy & Aghaee, 2022; Li & Yang, 2023; Zhao & Wang, 2023c; Zhao et al., 2023).

Many studies acknowledged the merit of grit in L2 learning across settings (MacIntyre & Khajavy, 2021; Mehdi et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021). For example, grit and the classroom environment influenced Chinese learners’ anxiety in online English learning (Li & Dewaele, 2021). The facilitating role of grit on enjoyment and English achievement has also been substantiated in the face-to-face classroom (Zhao & Wang, 2023a). However, a deeper knowledge of psycho-emotional factors and personality traits in L2 learning is constrained to three particular aspects. First, the exclusive focus on offline classes suggests little is known about how grit and emotions are experienced in online L2 learning (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). The Covid-19 pandemic has caused learners to experience diverse obstacles beyond physical aspects, such as internet disconnection, emotional isolation, and insufficient participation (MacIntyre et al., 2020; Wang & East, 2020; Wang & Zhao, 2020; Wang, 2023), and thus L2 achievement. This necessitates the utilization of grit and emotions to sustain their language success and emotional well-being. Ensuring the quality of online learning is also a new task in the post-pandemic era. Furthermore, the overly dominant attention on L2 English learning means insufficient understanding of this pattern in languages other than English (LOTE) (Zhang & Tsung, 2021; Zhao & Wang, 2023c; Zhao et al., 2023). As emotions are domain-specific, diverse emotion patterns and the relationship between L2 grit and emotions may emerge in different ways, warranting further investigation (Li & Yang, 2023; Pekrun, 2006; Wen et al., 2022). Lastly, adapting and validating instruments in LOTE should be encouraged because appropriate instruments with suitable reliability and validity are a prerequisite for conducting research (Elahi Shirvan et al., 2021).

The context and domain of this study are different from previous studies. Chinese as second language (CSL) learning has increased in popularity in China and abroad (Wang & Zhao, 2020). However, Mandarin Chinese has been noted to cause difficulties for learners due to the particular pronunciation and writing system (Kane, 2006; Wen et al., 2022). Such challenges negatively influence Chinese learners’ emotions, motivation, and determination. To better address this, obtaining a fulsome picture of the diverse emotional state that learners experience and the pattern of effects between grit and emotions is paramount to progressing their L2 learning.

To bridge these gaps, the current study seeks to understand university CSL learners' emotional profiles and advance the pattern between grit, enjoyment, boredom, and anxiety in online learning by employing structural equation modeling (N = 204). This attempt is significant as the robust empirical evidence provides a solid rationale for further investigating domain-specific grit in L2 learning across different populations, languages, and contexts.

Literature Review

Grit

Recent years have witnessed a proliferation of research into personality strength in L2 learning, yet the focus on grit remains in its infancy in SLA (Credé & Tynan, 2021). Grit has been considered a higher-order two-factor construct with two facets: perseverance of effort (POE) and consistency of interest (COI) (Duckworth et al., 2007). This concept encompasses three aspects. Firstly, a grittier person will invest time and continuous effort and stick to their goals for years no matter what challenges they may encounter. Secondly, they will retain a strong interest in the learning marathon. Thirdly, they need to have an explicit, well-defined goal that is not easily realized. Currently, there are two domain-general scales, Grit-O (six items for each dimension) and G-S (four items for each dimension), and one domain-specific L2 grit scale (five items for POE and four for COI) that have been adopted extensively in the literature (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009; Duckworth et al., 2007; Teimouri et al., 2020).

Numerous studies have confirmed grit’s facilitating role in L2 learning. For example, Zhao and Wang (2023a) identified the significant predictive power of POE and COI on foreign language enjoyment, boredom (FLE and FLLB), and English language achievement among ethnic-minority Chinese learners (n = 504). Analogously, Bensalem et al. (2023) found that a higher level of grit was followed by a more enjoyable learning experience among college-level Saudi Arabian (n = 228) and Moroccan (n = 218) learners. The merit of grit has also been substantiated among German language learners. For instance, Li and Yang (2023) indicated that domain-general grit and L2 grit were positively correlated with L2 English achievements (n = 700). However, in the Iranian context, Khajavy and Aghaee (2022) observed that only POE predicted English achievement (n = 226). A recent study by Zhao et al. (2023) found that grit indirectly predicts online Chinese learning through the role of FLE among Arabic learners (n = 169). Informed by prior studies, we argued that the merit of grit in L2 learning has yet to reach a consensus, necessitating further endeavors (Zhao & Wang, 2023c).

One question that needs to be resolved is the validation and promotion of the domain-specific grit scale across domains and contexts. Duckworth & Quinn (2009) have noted the maladaptive interpretation of reverse-coded items and statistical errors of the general grit scales. In addition, the psychometric properties of the domain-specific L2 grit scale have been confirmed to be better than the domain-general grit scale (Teimouri et al., 2020). Despite the call to substantiate the utility of the L2 grit scale in SLA (MacIntyre & Khajavy, 2021), few studies appear to have been published that examine L2 grit in LOTE (Li & Yang, 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Hence, addressing the gap across languages with a tailored instrument is a prerequisite for the promotion of grit-related research.

The other fundamental question that needs to be addressed is the structure of grit. Khajavy et al. (2021), Khajavy and Aghaee (2022), and Zhao and Wang (2023a) reported grit was a first-order two-factor structure for Chinese and Iranian English learners. Credé et al. (2017) and Credé and Tynan (2021) argued that the original higher-order two-factor model of grit should be overturned due to statistical errors. Yet, other researchers have considered or adopted grit as a higher-order two-factor structure in English language learning (Duckworth et al., 2007; Li & Dewaele, 2021). Such a divergence might lead to an inadequate understanding of the utility of grit (Credé et al., 2017). It is also dangerous to adopt L2 grit as a unitary construct without the preliminary factor structure validation as it might conceal the strength of POE and COI. Therefore, the factor structure of L2 grit in the online CSL learning context will be investigated first before involving it into the mechanism.

Anxiety, Boredom, and Enjoyment

Driven by the development of positive psychology, emotion has been viewed as a vital and unavoidable part of the L2 learning journey in SLA (Derakhshan et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023; Tsang & Dewaele, 2023). This development has shifted the focus from foreign language anxiety (FLA) to positive emotional constructs such as foreign language enjoyment (FLE), and it has also inspired an expanding body of literature regarding diverse negative emotions, specifically, foreign language learning boredom (FLLB) (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Wang, 2023; Zhao & Wang, 2023b). In addition, grounded in the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), the investigation of both positive and negative emotions such as FLE, FLLB, and FLA has gradually shed light on their facilitating or hindering effects on L2 learning across different contexts (Dewaele et al., 2023a, 2023b; Li et al., 2023; Shao et al., 2023).

The control-and-value theory has laid a solid foundation for diverse emotional research (Pekrun, 2006). According to the three-dimensional taxonomy, achievement-related emotions can be well defined from valence (positive or negative), activation (activating or deactivating), and object-focused (activity emotion or outcome emotion) perspectives. That is, FLE can be defined as a positive, activating, and activity-related emotion, FLA as a negative, deactivating, and outcome-related emotion, and FLLB as a negative, deactivating, and activity-related emotion (Li & Li, 2023). In addition, as an achievement emotion, enjoyment has been assumed to reinforce the learner’s learning motivation and academic achievement, while FLLB and FLA have the reverse effect in the L2 learning setting.

In terms of the instruments, eleven items covering three dimensions (FLE-private, FLE-teacher, and FLE-atmosphere) from the Chinese version of the FLE scale (Li et al., 2018) have been widely adopted to assess the enjoyment level of language learners. These items were originally adapted from the 21-item scale created by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) for the English language learning context. Thirty-two items have been widely used to measure the perception of boredom in language learning (seven types: foreign language class boredom; under-challenging task boredom; PowerPoint presentation boredom; homework boredom; teacher-dislike boredom; general learning trait boredom; and over-challenging or meaningless task boredom) (Li et al., 2023). To investigate anxiety levels, eight items were taken from the short version of the foreign language classroom anxiety scale developed by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014), which was developed from the 33-item anxiety scale (Horwitz et al., 1986). To our knowledge, items in these instruments have been widely adopted and validated in L2 English learning except for several items in the CSL learning field. For example, Wen et al. (2022) found that FLLB was a three-dimensional structure (classroom boredom, content boredom, and teacher boredom) in online Chinese learning (n = 348). Zhang and Tsung (2021) identified the three-factor structure of FLE (personal fulfillment, interpersonal relations, and social bonds) in university L2 Chinese learners (n = 216).

Understanding of the interconnections between FLE, FLLB, and FLA has recently flourished, influenced by the adoption of a more holistic view (Dewaele et al., 2023a, 2023b; Li & Li, 2023). For example, Dewaele et al. (2023a, 2023b), Li and Li (2023), Shao et al. (2023), and Tsang and Dewaele (2023) reported FLE was negatively correlated with FLLB and FLA, but FLLB and FLA were positively associated with each other in English learning among Chinese university students (n = 1,021), Chinese secondary school students (n = 954), international samples (n = 332), and Chinese (Hong Kong) primary school students (n = 111). The complex interaction between those emotions appears to have been established, considering the evidence across languages, domains, and contexts. Yet, underexplored contexts remain, and one such is the CSL online learning context during the pandemic.

Grit and Emotions

Personality traits, emotions (both positive and negative), and institutions act as three fundamental pillars in positive psychology, promoting the development of an individual (Seligman, 2012). In recent years, grit and emotion have been empirically considered two significant non-cognitive factors that interplay and interconnect to predict a learner’s success in L2 learning (Khajavy & Aghaee, 2022; Li & Yang, 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

Robust evidence shows the complex relationship between grit and emotion in English learning. Li and Dewaele (2021, n = 1526) and Zhao and Wang (2023a, n = 504) found grit positively predicted FLE but negatively predicted FLLB and FLA in the Chinese English as a foreign language (EFL) learning context. Of the three emotions, grit was considered a positive predictor of joy but a negative predictor of FLA (Teimouri et al., 2020). Pawlak et al. (2022) stated that FLA negatively predicted COI and perceived language competence, and FLE positively predicted motivated behavior, POE, and COI among Iranian university learners (n = 238). However, unexpectedly, L2 boredom positively predicted COI. In the same context, Khajavy and Aghaee (2022) revealed that both POE and COI predicted L2 anxiety, while only POE positively predicted L2 enjoyment and personal-best goals among university learners.

It is clear that the intricate association between grit components and a constellation of emotions (FLA, FLLB, and FLE) in online learning has yet to reach a consensus in the currently published literature. Furthermore, existing studies mainly focus on EFL learning in Chinese and Iranian contexts, no evidence has yet been provided on this pattern in CSL learning, specifically in the online context. As emotion is domain-specific (Pekrun, 2006), we thus argue that the perception and the pattern between emotion and L2 grit may vary in online L2 Chinese learning, requiring further investigation to improve the current knowledge.

Online Language Learning Context

The unexpected Covid-19 pandemic has substantially affected face-to-face classroom instruction. Alongside the sudden transition to online learning, noted difficulties, such as isolation, internet disconnection, and lack of support, occurred in academic learning and teaching (MacIntyre et al., 2020; Wang, 2023). These difficulties unavoidably affected L2 learners’ emotional state and language achievement (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023), warranting further investigation to deepen our understanding due to the domain-specificity of emotions.

Some empirical research confirmed the adverse conditions of online L2 learning. In EFL learning context, Resnik and Dewaele (2023) discovered that students perceived more enjoyment and anxiety offline as sufficient emotional resonance based on 510 international university learners. Analogously, by comparing the emotional difference between 168 Arabian and Kurdish EFL learners, Dewaele et al. (2022) found that remote online learners perceived less enjoyment and anxiety, but a higher level of boredom. A recent study by Zhao et al. (2023) revealed an intriguing finding. They observed that students’ perceptions of enjoyment and anxiety were close to the online English learning in online CSL learning. From English teachers’ perspectives, Wang (2023) suggested that the online learning context caused more boredom. Additionally, task-related, IT-related, and teacher-related factors were significant antecedents of online boredom. In a mixed-method study, Yuan (2023) found that Chinese university learners had a moderately elevated level of FLE and FLA in English online learning.

As demonstrated by previous research, only a handful of studies have examined the relationship between grit and emotions in English language learning in the online context, let alone sought to validate this pattern in CSL online learning. As findings may vary across languages, participants, and domains (Zhao & Wang, 2023a), this study aims to increase understanding of Chinese learners’ emotional states and how grit and emotions work in the online CSL learning context. By doing so, L2 learners could be more receptive to blended learning and e-learning (Wang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023), and their language learning might progress more smoothly and swiftly.

The Present Study

To address the identified gaps, this study poses the following research questions:

-

RQ1: What are participants’ L2 grit and emotional profiles in Mandarin Chinese online learning?

-

RQ2: Does L2 grit significantly predict enjoyment, boredom, and anxiety in Mandarin Chinese online learning?

Methodology

Participants and Contexts

This study adopted a convenience sampling approach by collecting valid responses from 204 university students from 11 intact classes at a public university in Mainland China. Participants were those studying Chinese as L2, aged between 18 and 55 (M = 21.1, SD = 6.21). Chinese language classes were compulsory for all participants, with eight 60-min classes per week. Detailed information is presented in Table 1.

The university is located in a coastal city in southern China. It is one of the key universities that supports the training of teachers for CSL teaching in neighboring countries, and is one of the universities with the largest number of international students learning the Chinese language in China (MOE, 2013). This university features an immersion environment for students to learn Chinese through a large amount of input and output in in-person classes. However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic emergency, in-person learning was forced to move online in China in early 2020, with courses delivered via an online teaching platform (ClassIn). Therefore, during the data collection phase, participants of the present study were learning Chinese in their home country through the online platform. The sudden transfer of teaching and learning to virtual online classrooms undoubtedly led to an array of physical, psychological, technical, and academic difficulties, which deserve further attention.

Instruments

A composite questionnaire was employed when collecting data. Section one collected participants’ demographic information, including age, gender, nationality, and university major. Section two measured the variables (L2 grit, enjoyment, boredom, and anxiety) through four Likert scales, where the possible range for each item is from 1 (the lowest) to 5 (the highest). Mean values below 3 indicate a low level of emotion, 3 to 4 represents a medium level, and scores above 4 indicate a high level of emotion (Zhao & Wang, 2023a). To enhance accessibility and comprehension of the questionnaire, all items were written in both Mandarin Chinese and English. This study adds “in the L2 Chinese online learning” to each statement to fit the current context. All items featured in the instrument for this study are provided in the Appendix.

L2 Grit

The L2 grit scale consists of two facets (POE and COI) with six items, extracted and adapted from the previous L2 grit scale (Teimouri et al., 2020), which has good reliability and validity across various contexts (Lee & Taylor, 2022; Sudina & Plonsky, 2021). The sample item is, “I often set a goal but later choose to pursue a different one in learning Chinese online”. Four items of the POE facet were reverse-coded, whereby a higher score indicates a lower level of grit. The Cronbach α coefficient was 0.722, which was above the cut-off value of 0.70, indicating a good internal consistency of the L2 grit scale.

Enjoyment

To measure participants’ perception of enjoyment, this study extracted and adapted ten items from Li et al. (2018), originally adapted from a 21-item scale by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014). It contains three dimensions, including FLE-private, FLE-teacher, and FLE-atmosphere. A sample item is “I don’t get bored in online Chinese learning”. A higher score on this scale represents a higher perception of enjoyment in learning Chinese. The Cronbach α coefficient was 0.849.

Boredom

Thirteen items were adopted to explore participants’ perceptions of boredom in L2 Chinese learning. The current study adopted two dimensions, language class boredom and teacher-dislike boredom, based on the scales used by Li et al. (2023). We added a peer-related dimension after considering the possibility that learners may be prone to affective effects from their peers in the classroom learning. A higher rating score indicates a more robust perception of boredom in the online CSL learning. The L2 boredom scale has an excellent internal consistency, with the Cronbach α coefficient reaching as high as 0.905.

Anxiety

To investigate participants’ perception of anxiety, four items were extracted and adapted from the eight original items of the scale developed by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014), which itself was a condensed version of the 33-item FLA scale (Horwitz et al., 1986). A sample item is “I can feel nervous when I’m going to be called on in Chinese class”. A higher score on this scale represents a higher perception of anxiety in CSL online learning, in addition to two reverse coded items. The Cronbach α coefficient was 0.873, indicating an excellent internal consistency.

Data Collection

This study was approved by the Human Participants Ethics Committee of the author’s university. After obtaining the official approval document, the first author contacted the target university’s dean and classroom instructor for their support and permission to conduct the current study. We informed instructors and volunteer participants of the study’s aim, procedure, time duration, anonymity, and confidentiality. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the current research without any consequences.

To collect the quantitative data, the online questionnaire was distributed by each classroom instructor through Wenjuanxing (an online data collection tool) from October 20th to December 5th, 2022, due to differences in the participants’ mid-term examinations’ schedule. Before answering the questionnaire, 209 students signed the consent form and indicated their willingness to voluntarily participate in the questionnaire survey.

Data Analysis

SPSS 24 and Amos 24 were utilized to process the quantitative data and investigate the two research questions. After receiving the responses, a series of preliminary steps, such as removing outliers (n = 5) who responded to the questionnaire within a short timeframe and answered consecutive questions with the same response, were employed. A check for normal distribution was conducted, which indicated 204 valid responses could be used in the following analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the current study’s construct validity and measurement model. Each scale’s discriminant and convergent validity (the composite reliability, CR; average variance extracted, AVE) was also calculated.

To explore research questions, descriptive analysis (M and SD) was used to assess participants’ grit and emotional level (RQ1). The structural equation model (SEM) was adopted to examine the relationships between L2 grit, enjoyment, boredom, and anxiety in online CSL learning (RQ2).

Results

Good preliminary results ensured the following analysis. The skewness and kurtosis of all the scales ranged from − 0.591 to 0.806 and − 0.434 to 0.845, which fell well between ± 2, indicating the normal distribution of the current data (Roever & Phakiti, 2017). The Cronbach α coefficient was 0.737, above the cut-off value of 0.70, indicating a good internal consistency of this study (Hair et al., 2019). Nine items were removed (three items from L2 grit, one item from enjoyment, two items from boredom, and three items from anxiety) due to the lower factor loading based on the results of CFA (Hair et al., 2019).

This study identified L2 grit as a first-order two-factor model (POE and COI), enjoyment as a second-order three-factor model (FLE-private, FLE-teacher, and FLE-atmosphere), boredom as a second-order three-factor model (Classroom boredom, teacher-related boredom, and peer-related boredom), and anxiety as one-factor model. A series of indices of CFA indicated the model fit was adequate to the data, with Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.931 > 0.90), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI = 0.912 > 0.90), Root Means Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.071 < 0.80), and Standardized Root Means Squared Residual (SRMR = 0.064 < 0.80) (Kline, 2011). Illustrated in Table 2, each variable demonstrated good convergent and divergent validity (the square root of the AVE is greater than the correlation among factors) (Hair et al., 2019).

The L2 Grit and Emotions Level

Table 3 illustrates the descriptive statistical analysis of Chinese language learners’ grit and emotional level in online learning. The results demonstrate a higher level of enjoyment, grit, anxiety, and a lower perception of boredom during the learning process. A subset (n = 124) of Chinese learners had a moderate-high and high level of COI (60.8%), and 186 learners reported a moderate-high and high level of POE (91.2%). It is worth noting that all Chinese learners reported a moderate-high and high level of enjoyment. As for the perception of negative emotions, half of all Chinese learners felt moderate-high and high-level anxiety, while only 0.05% of learners experienced the same level of boredom in online Chinese learning.

The Relationship Between L2 Grit and Emotions

To investigate the relationship of the different factors, correlation analysis among factors was statistically evaluated (see Table 4). The results indicate that students’ POE was positively correlated with enjoyment (r = 0.539, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with boredom (r = − 0.325, p < 0.01) and anxiety (r = − 0.193, p < 0.01). Conversely, there was no significant correlation between COI and those factors. In addition, enjoyment was negatively correlated with boredom (r = − 0.400, p < 0.01) and anxiety (r = − 0.163, p < 0.05). Anxiety was positively correlated with boredom (r = 0.327, p < 0.01).

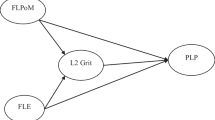

Subsequently, an advanced statistical analysis, SEM, was employed to further capture the intricate relationship among factors in online CSL learning, that is, the predictive effect of POE and COI on enjoyment, boredom, and anxiety, and the relationship among emotional factors. Based on a first-order two-factor model of grit, POE and COI were separately entered into the proposed SEM (Fig. 1).

The goodness-of-fit indices of the proposed SEM model indicated that it was adequate for the data (χ2/df = 2.013; CFI = 0.931; TLI = 0.912; RMSEA = 0.071; SRMR = 0.064), which indicated that further path analysis was appropriate (Hair et al., 2019).

After further investigation of the relationship between factors in online CSL learning, we found that only POE significantly and positively predicted enjoyment (t = 8.457, p < 0.001), and it significantly and negatively predicted anxiety (t = − 2.62, p = 0.006) in CSL online learning. Enjoyment significantly and negatively predicted boredom (t = − 3.27, p = 0.001). Anxiety significantly and positively predicted boredom (t = 3.5, p < 0.001). Notably, no paths were statistically significant from COI to the three emotions in online Chinese learning (see Table 5 and Fig. 2).

Discussions

The current study investigated the emotional profile of CSL university learners, and the relationship between grit and three frequently experienced classroom emotions in CSL online learning.

Regarding RQ1, we found a very high level of enjoyment, a moderate to high level of anxiety and grit, and a low level of boredom in the online CSL learning context. This corroborates previous results that language learning is a complex emotional activity. That is, diverse classroom emotions might appear simultaneously at the same time. In addition, a high level of positive emotion does not equate to the non-appearance of negative emotions (Li & Li, 2023; Zhao & Wang, 2023a).

However, it is interesting that CSL learners in the present context felt more enjoyment compared to online English language learners (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Yuan, 2023). This might be attributed to the domain-specificity of emotions (Pekrun, 2006; Shao et al., 2023). In other words, the features and patterns of emotions will differ across subjects and domains (Wen et al., 2022; Zhang & Tsung, 2021; Zhao et al., 2023), validating the control-and-value theory in the Chinese learning sphere. Furthermore, students’ enjoyable experience in online learning may result from their satisfaction toward teacher, which regarded as the main source of enjoyment (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Yuan, 2023). Given this, distance online learning does not necessarily add a negative emotional burden and cause disastrous experiences but instead has the potential to maintain a joyful learning experience in L2 learning.

RQ2 aimed to uncover the predictive effect of POE and COI on three emotions in online CSL learning. The findings pointed out that only POE significantly predicted FLA and FLE, indicating that an individual who expends committed effort will likely perceive more enjoyment and less anxiety and persist in the face of difficulties. Such a result converged with the findings of Credé et al. (2017) and Khajavy and Aghaee (2022) in that POE promoted students’ achievement and enjoyment, while COI had a weak or no statistical effect. A possible explanation for this might be that participants of the current study mainly come from Asian countries and regions along the “One Belt One Road” initiative. This Chinese program aims to develop students’ language talent and facilitate their job hunting after graduation from this university. Thus, participants are strongly motivated to pursue further study or make a living through learning Chinese, encouraging them to invest time and effort in a distance remote learning context despite their perception of boredom or anxiety. As such, an important finding is that POE may be the core to promoting the L2 success of adult learner; that is, pure learning interest is futile without continued effort in language learning (Credé et al., 2017; Khajavy & Aghaee, 2022). External motivation might be the key to fueling adult Chinese learners to stick to the goal in L2 learning. Future studies could further validate or expand this result across domains and subjects.

In addition, POE failed to predict learner boredom as the perception of boredom was far lower than that of other emotions. It is also not as debilitative as anger and anxiety in impeding L2 learning experiences and outcomes within a short period (Pawlak et al., 2020). However, enjoyment and anxiety significantly predicted boredom in CSL online learning, corroborating previous empirical findings (Dewaele et al., 2023a, 2023b; Shao et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). Based on the broaden-and-build theory, positive emotion has merit in expanding the ‘momentary thought-action repertoire’ (Fredrickson, 2001, p. 1367), while negative emotion acts in the opposite fashion. In L2 learning, the experience of anxiety may narrow learner’s classroom engagement and intellectual resources, further inducing a greater perception of boredom in the learning process. Additionally, positive emotions have a dissimilating effect on their negative counterparts (Fredrickson, 2001). That is, enjoyment has merit in counteracting the negative effects of boredom. In addition to the above, the current study adapted and validated the L2 grit and emotion scales in the Chinese language sphere, lending support for the future related research.

Conclusions, limitations, and implications

The shift from the in-person context to an online learning environment has produced multiple challenges for language learners (Li & Dewaele, 2021; Resnik & Dewaele, 2023). The current study was typically conducted to better understand the pattern between L2 grit and frequently appeared emotions, to cope with special challenges in the unique CSL context (Wang & East, 2020; Wang & Zhao, 2020). The results here demonstrated that the adapted scales utilized had adequate reliability and validity in this context. The psychological state of CSL learners in the online context is similar to the traditional classroom profile, with a high level of enjoyment, a low or moderate to high level of boredom and anxiety while learning Chinese. In addition, POE, rather than COI, was the only significant predictor of enjoyment and anxiety. Enjoyment negatively predicted boredom, while anxiety positively predicted boredom in online CSL learning.

The current research was limited from several perspectives. Firstly, participants mainly came from Asian countries, leading to an incomplete picture of L2 grit in the online environment due to the somewhat monocultural context. Future studies are necessary in order to validate this pattern across different contexts and participants. Secondly, this purely quantitative research fails to confirm the reasons why the effect of POE was stronger than COI in online CSL learning. Mixed-method studies are needed to explore the reasons for this through the addition of qualitative data. Thirdly, novel approaches, as Derakhshan et al. (2023) argued, multilevel modeling, time series analysis, and latent growth curve modeling could also be employed to capture the nature of multifaceted emotions in L2 learning. In addition, it would be more interesting and groundbreaking if future research would consider the third pillar of positive psychology, the positive institution in the mechanism, especially through a longitudinal study design (Elahi Shirvan et al., 2021).

This study also provides pedagogical and theoretical implications for teachers’ professional development and the growth of the discipline. To start with, L2 learning is a complex psychological activity. Positive and negative emotions are intertwined and co-exist, whether in an online class or an offline class. Therefore, language teachers do not need to feel distressed about learners’ perception of diverse emotions in unfamiliar distance learning. In addition, online L2 learning does not mean a lower perception of positive emotion than a face-to-face class. The teacher plays a crucial role in influencing learners’ experience and language achievement (Fan & Wang, 2022; Wen et al., 2022). Given this, employing interesting teaching content and thought-provoking topics, applying related videos, giving appropriate praise and encouragement, being friendly, and equipping themselves with technology ability are essential to providing an enjoyable L2 experience (Resnik & Dewaele, 2023; Yuan, 2023). Moreover, it appears that only one facet of grit, POE, fosters learners’ emotions in CSL learning, dwarfing the role of COI. Given this, inspiring learners to make continuous effort through external motivations in the learning process should be prioritized as it is essential for adult learners to continue learning.

Researchers are advised to carefully consider the separate role of grit dimensions and the factor structure of grit. In addition, the high perception of enjoyment in the context of the current study echoed the domain-specificity of emotions (Pekrun, 2006), encouraging in-depth discussion and validation of the different patterns of emotion as well as the relationship between L2 grit and emotions, across domains and contexts, in order to progress the contribution of positive psychology to SLA (MacIntyre & Khajavy, 2021).

References

Bensalem, E., Thompson, A. S., & Alenazi, F. (2023). The role of grit and enjoyment in EFL learners’ willingness to communicate in Saudi Arabia and Morocco: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2200750

Credé, M., & Tynan, M. C. (2021). Should language acquisition researchers study “Grit”? A cautionary note and some suggestions. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 3(2), 37–44.

Credé, M., Tynan, M. C., & Harms, P. D. (2017). Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000102

Derakhshan, A., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). Towards innovative research approaches to investigating the role of emotional variables in promoting language teachers’ and learners’ mental health. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 25(7), 823–832. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029877

Dewaele, J. M., Albakistani, A., & Ahmed, I. K. (2022). Levels of foreign language enjoyment, anxiety and boredom in emergency remote teaching and in in-person classes. The Language Learning Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2022.2110607

Dewaele, J. M., Botes, E., & Greiff, S. (2023a). Sources and effects of foreign language enjoyment, anxiety, and boredom: A structural equation modeling approach. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(2), 461–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263122000328

Dewaele, J. M., Botes, E., & Meftah, R. (2023b). A Three-Body Problem: The effects of foreign language anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom on academic achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190523000016

Dewaele, J. M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 237–274. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Elahi Shirvan, M., Taherian, T., & Yazdanmehr, E. (2021). Foreign language enjoyment: A longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis–curve of factors model. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1874392

Fan, J., & Wang, Y. (2022). English as a foreign language teachers’ professional success in the Chinese context: The effects of well-being and emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.952503

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning EMEA.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125–132.

Kane, D. (2006). The Chinese language: Its history and current usage. Tuttle Publishing.

Khajavy, G. H., & Aghaee, E. (2022). The contribution of grit, emotions and personal bests to foreign language learning. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2047192

Khajavy, G. H., MacIntyre, P. D., & Hariri, J. (2021). A closer look at grit and language mindset as predictors of foreign language achievement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(2), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000480

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Lee, J. S., & Taylor, T. (2022). Positive psychology constructs and extramural English as predictors of primary school students’ willingness to communicate. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2079650

Li, C., & Dewaele, J. M. (2021). How classroom environment and general grit predict foreign language classroom anxiety of Chinese EFL students. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 3(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/3/2/6

Li, C., Dewaele, J. M., & Hu, Y. (2023). Foreign language learning boredom: Conceptualization and measurement. Applied Linguistics Review, 14(2), 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2020-0124

Li, C., Jiang, G., & Dewaele, J. M. (2018). Understanding Chinese high school students’ foreign language enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the foreign language enjoyment scale. System, 76, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.06.004

Li, C., & Li, W. (2023). Anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom in language learning amongst junior secondary students in rural China: How do they contribute to L2 achievement? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263122000031

Li, C., & Yang, Y. (2023). Domain-general grit and domain-specific grit: Conceptual structures, measurement, and associations with the achievement of German as a foreign language. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2022-0196

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System, 94, 102352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

MacIntyre, P., & Khajavy, G. H. (2021). Grit in second language learning and teaching: Introduction to the special issue. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 3(2), 1–6.

Mehdi, S., Derakhshan, A., & Ünsal, B. (2023). Associations between EFL students’ L2 grit, boredom coping strategies, and emotion regulation strategies: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2175834

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2013). http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s6192/s222/moe_1745/201308/t20130802_154989.html

Pawlak, M., Kruk, M., Zawodniak, J., & Pasikowski, S. (2020). Investigating factors responsible for boredom in English classes: The case of advanced learners. System, 91, 102259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102259

Pawlak, M., Zarrinabadi, N., & Kruk, M. (2022). Positive and negative emotions, L2 grit and perceived competence as predictors of L2 motivated behaviour. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2091579

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.583

Resnik, P., & Dewaele, J. M. (2023). Learner emotions, autonomy and trait emotional intelligence in ‘in-person’ versus emergency remote English foreign language teaching in Europe. Applied Linguistics Review, 14(3), 473–501. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2020-0096

Roever, C., & Phakiti, A. (2017). Quantitative methods for second language research: A problem-solving approach. Routledge.

Seligman, M. E. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

Shao, K., Stockinger, K., Marsh, H. W., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Applying control-value theory for examining multiple emotions in L2 classrooms: Validating the achievement emotions questionnaire–Second Language Learning. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221144497

Sudina, E., & Plonsky, L. (2021). Academic perseverance in foreign language learning: An investigation of language-specific grit and its conceptual correlates. The Modern Language Journal, 105(4), 829–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12738

Teimouri, Y., Plonsky, L., & Tabandeh, F. (2020). L2 grit: Passion and perseverance for second-language learning. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820921895

Tsang, A., & Dewaele, J. M. (2023). The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, & enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency. Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0077

Wang, Y. (2023). Probing into the boredom of online instruction among Chinese English language teachers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Current Psychology, 43(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04223-3

Wang, D., & East, M. (2020). Constructing an emergency Chinese curriculum during the pandemic: A New Zealand experience. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching, 1(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijclt.2020.06.01

Wang, D., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Introduction to the special issue of “A digital future of Chinese language teaching”. International Journal of Chinese Language Teaching, 1(1), I-V. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijclt.2020.06.06

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: The past, current status and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wang, Y., Pan, Z. W., & Wang, M. Z. (2023). The moderating effect of participation in online learning on EFL teachers’ teaching ability. Heliyon, 9(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13890

Wen, C., Peizhen, S., & Zishuo, Y. (2022). Understanding Chinese second language learners’ foreign language learning boredom in online classes: Its conceptual structure and sources. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2093887

Yuan, R. (2023). Chinese university EFL learners’ foreign language classroom anxiety and enjoyment in an online learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2023.2165036

Zhang, L., & Tsung, L. (2021). Learning Chinese as a second language in China: Positive emotions and enjoyment. System, 96, 102410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102410

Zhao, X., Sun, P. P., & Gong, M. (2023). The merit of grit and emotions in L2 Chinese online language achievement: A case of Arabian students. International Journal of Multilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2023.2202403

Zhao, X., & Wang, D. (2023a). Grit, emotions, and their effects on ethnic minority students’ English language learning achievements: A structural equation modelling analysis. System, 113, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.102979

Zhao, X., & Wang, D. (2023b). The role of enjoyment and boredom in shaping English language achievement among ethnic minority learners. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2194872

Zhao, X., & Wang, D. (2023c). Grit in second language acquisition: a systematic review from 2017 to 2022. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1238788. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1238788

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: The instruments of the current study

Appendix: The instruments of the current study

1. I am a diligent Chinese language learner in online learning. (L2 grit: POE) |

2. When it comes to Chinese, I am a hard-working learner |

3. I will not allow anything to stop me from my progress in online Chinese learning |

4. I think I have lost interest in online Chinese learning. (L2 grit: COI) |

5. I am not as interested in learning Chinese as I used to be in online Chinese learning |

6. I have been obsessed with learning Chinese in the past but lost interest recently |

7. I don’t get bored with online Chinese learning. (Enjoyment: private) |

8. I enjoy learning Chinese online |

I’ve learned interesting things in the online Chinese learning process |

9. Learning Chinese online is fun |

10. The Chinese teacher is encouraging in the online learning context. (Enjoyment: teacher) |

11. The Chinese teacher is friendly in the online learning context |

12. The Chinese teacher is supportive in the online learning context |

13. There is a positive Chinese learning environment around me in the online learning context. (Enjoyment: atmosphere) |

14. I have a good Chinese learning atmosphere in the online learning context |

15. We form a tight group in the online learning context |

16. The online Chinese class is boring. (Boredom: classroom boredom) |

17. I feel sleepy in online Chinese class |

18. I tend to be stunned in online Chinese class |

19. I am only physically in the classroom, while my mind is wandering outside the online Chinese class |

20. Time is dragging on in online Chinese class |

21. I get restless and can’t wait for the online Chinese class to end |

22. I always try to kill the time rather than focusing on the online Chinese class |

23. I am not interested in online Chinese class, because the Chinese teacher isn’t likable (e.g., tone, pitch, or facial appearance). (Boredom: teacher boredom) |

24. I dislike the Chinese teacher spending so much time making personal comments |

25. I feel agitated because the Chinese teacher spends too much time saying things that are irrelevant to the teaching material in online classes |

26. If I cannot understand what my classmates’ say, I become bored with online Chinese learning. (Boredom: peer boredom) |

27. My peers are unwilling to participate in class activities and answer questions, making me feel bored with online Chinese learning |

28. The peer is uninteresting, so the online Chinese class is dull |

29. I always think that the other students speak Chinese better than I do in online classes. (Anxiety) |

30. I get nervous and confused when speaking Chinese in an online class |

31. I start to panic when I have to speak without preparation in an online Chinese class |

32. It embarrasses me to volunteer answers online Chinese class |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, X., Wang, D. Domain-Specific L2 Grit, Anxiety, Boredom, and Enjoyment in Online Chinese Learning. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 33, 783–794 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00777-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00777-3