Abstract

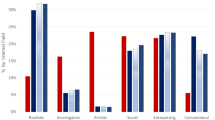

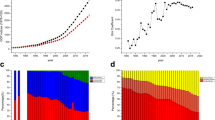

In this paper, we examine gender difference effects of education on first occupational achievement after completing final education in South Korea. Although numerous researchers have examined women’s labor market outcomes, few studies have focused systematically on the impacts of gender on occupational achievement. Using the 1998 and 2001 Korean Labor and Income Panel Survey data sets, we found better performance for women than men except for junior secondary level and below education. We also found a disruption of gap years between starting jobs and graduation to occupational prestige score for women only, and that the negative effect was worse for tertiary-educated women. We further found that women entering the labor market much later after graduation obtained fewer benefits than their peers. We suggest that our specific focus on Korea actually adds to the understanding of all women’s education and occupational achievement internationally. We therefore conclude that the interrelationship between gender, education, and the time gap should be considered when studying occupational achievement. The implication of these interrelationships is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A primary market offers relatively high-paying, stable employment with good working conditions; a secondary market is less attractive in all of these respects.

However, it has been found that income and interpersonal power are less for women than for men (England 1979).

Note that the sampling criteria in the KLIPS data are based on respondents living in relatively urbanized areas; therefore, the number of respondents giving farming class for their first occupation is somewhat smaller than the national figure. Information about the survey design and sampling procedure is available in both Korean and English at http://www.kli.re.kr/klips/en/research/study_design.jsp.

After final education graduation, the work experience rate is higher for men (98 %) than women (88 %). Women’s lower work experience may cause a sample selection effect, but since the relationship between education and work experience is not systematic and indeed slightly less than 90 % of all female respondents who had work experience, we expect that the result will not cause a serious problem.

The educational attainment has increased, and in 2011 the proportion of junior secondary and below, upper-secondary, and tertiary education are 20.4, 38.3, and 41.4 % for men and 33.7, 35.6, and 30.6 % for women, respectively, among the adult population aged 25 years and above (Statistics Korea 2012).

Military service (2 or 3 years) is compulsory for Korean men.

References

Amsden, A. H. (1989). Asia’s next giant: South Korea and late industrialization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arum, R., & Hout, M. (1998). The early returns: The transition from school to work in the United States. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 471–510). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special references of education. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bose, C. E., & Rossi, P. H. (1983). Gender and jobs: Prestige standings of occupations as affected by gender. American Sociological Review, 48(3), 316–330.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity, and social inequality: Changing prospects in western society. New York, NY: Wiley.

Breen, R., & Whelan, C. T. (1998). Investment in education: Educational qualifications and class of entry in the Republic of Ireland. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 189–219). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Bridges, J. S. (1989). Sex differences in occupational values. Sex Roles, 20, 205–211.

Brinton, M. C., & Lee, Y. (2001). Women’s education and the labor market in Japan and South Korea. In M. C. Brinton (Ed.), Women’s working lives in East Asia (pp. 125–150). Standford, CA: Standford University Press.

Brinton, M. C., Lee, Y., & Parish, W. L. (2001). Married women’s employment in rapidly industrializing societies: South Korea and Taiwan. In M. C. Brinton (Ed.), Women’s working lives in East Asia (pp. 38–69). Standford, CA: Standford University Press.

Cameron, L. A., Dowling, M., & Worswick, C. (2001). Education and labor market participation of women in Asia: Evidence from five countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49(3), 459–477.

Chang, S. S. (1999). Educational credentials and labor market entry in Korea: Transition from school to work. The Korean Journal of Sociology, 33, 751–787.

Chang, S. S. (2001). Social mobility in South Korea. Seoul: Seoul National University Press.

Chen, R. S., & Tsai, C. C. (2007). Gender differences in Taiwan university students’ attitudes toward web-based learning. Cyber-Psychology & Behaviors, 10, 645–654.

Cheng, S. S., Liu, E. Z. F., & Chen, N. S. (2012). Gender differences in college students’ behaviors in an online questions-answer discussion activity. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 21(2), 245–256.

Chin, S. H. (1995). The determinant and patterns of married women’s labor force participation in Korea. Korea Journal of Population and Development, 24(1), 95–129.

Chosun D. (2008). Illiteracy rate. Retrieved June 10 2012 from http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2008/12/23/2008122300050.html.

Dahlma, C. J., & Andersson, T. (2000). Korea and the knowledge-based economy: Making the transition. Washington, DC: World Bank, OECD.

England, P. (1979). Women and occupational prestige: A case of vacuous sex equality. Signs, 5(2), 252–265.

Erikson, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (1998). Qualifications and the allocation process of young men and women in the Swedish labour market. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 369–406). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Fox, J., & Suschnigg, C. (1989). A note on gender and the prestige of occupations. The Canadian Journal of Sociology, 14(3), 353–360.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., & Treiman, D. J. (1996). Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1998 International Standard Classification of Occupation. Social Science Research, 25, 201–239.

Garćia-Aracil, A. (2007). Gender earnings gap among young European higher education graduates. Higher Education, 53, 431–455.

Goux, D., & Maurin, E. (1998). From education to first job: The French case. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 369–406). Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press.

Goyder, J. (2005). The dynamics of occupational prestige: 1975–2000. The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 42(1), 1–23.

Graaf, P. M. D., & Ultee, C. W. (1998). Education and early occupation in the Netherlands around 1990: Categorical and continuous scales and the details of a relationship. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 337–367). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hakim, C. (2004). Key issues in women’s work: Female diversity and the polarisation of women’s employment. London: The GlassHouse Press.

Heath, A. F., & Cheung, S. Y. (1998). Britain: Education and occupation. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 71–101). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hwang, S. K. (2003). Women’s job choices and the structure of employment. Seoul: KLI.

Hwang, S. K., & Chang, J. (2004). Female labor supply and labor policies for female workers. In W. Lee (Ed.), Labor in Korea, 1987–2002 (pp. 333–370). Seoul: Korea Labor Institute.

Ishida, H. (1998). Educational credentials and labour-market entry outcomes in Japan. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 287–309). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Jacobsen, J. P. (1998). The economics of gender (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Jang, H. K. (2008). Reviews on studies on occupational prestige scores. International Labor Brief, 6(4), 119–124.

Jung, Y. K. (2003). Women’s lives and work. Seoul: Sigma Press.

Kalleberg, A. L., & Sorensen, A. B. (1979). The sociology of labor markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 5, 351–379.

Korea Labor Institute (KLI). (2004). KLIPS user guide. Seoul: KLI.

Korea Ministry of Culture & Education. (1988). 40 years of education and culture. Seoul: Korea Ministry of Culture & Education.

Korea Women’s Development Institute (KWDI). (1991). Status of women in Korea. Seoul: Korean Women’s Development Institute.

Kum, J. H. (2002). The situations and issues of the female labor market. Seoul: KLI.

Lee, M. J. (1997). The meaning of women’s education as human capital. The Korean Journal of Population, 20(2), 135–159.

Lee, S. H. (2001). Women’s education, work, and marriage in South Korea. In M. C. Brinton (Ed.), Women’s working lives in East Asia (pp. 204–232). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Mastekaasa, A., & Smeby, J. C. (2008). Educational choice and persistence in male- and female-dominated fields. Higher Education, 55(2), 189–202.

Mincer, J., & Ofek, H. (1982). Interrupted work careers: Depreciation and restoration of human capital. Journal of Human Resources, 17(1), 3–24.

Müller, W., & Shavit, Y. (1998). The institutional embeddedness of the stratification process: A comparative study of qualifications and occupations in thirteen countries. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 1–48). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

OECD. (2006). Employment outlook 2006: Boosting jobs and incomes. Paris: OECD.

Okamoto, D., & England, P. (1999). Is there a supply side to occupational sex segregation? Sociological Perspectives, 42(4), 557–582.

Park, S. M. (2002). The effect of Korean women’s human capital on the employments. The Korean Journal of Populations, 25(1), 113–143.

Park, H. J. (2003). Education and first occupational attainment among Korean women: Trends in the association. The Korean Journal of Population, 26(1), 143–170.

Piore, M. J. (1969). On-the job training in the dual labor market. In A. R. Weber, F. H. Cassell, & W. L. Ginsberg (Eds.), Public-private manpower policies (pp. 101–132). Wisconsin: Industrial Relations Research Institute, University of Wisconsin.

Reich, M., Gordon, D. M., & Edwards, R. C. (1973). A theory of labor market segmentation. The American Economic Review, 63(2), 359–365.

Rubery, J., Smith, M., & Fagan, C. (1999). Women’s employment in Europe: Trends and prospects. London: Routledge.

Sandefur, G. D., & Park, H. J. (2007). Educational expansion and changes in occupational returns to education in Korea. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 25(4), 306–322.

Seong, M. (2009). Gender comparison in the effect of education on the labor market. Journal of Women’ Discussion, 26(1), 109–134.

Song, B. N. (1994). The rise of the Korean economy. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Standing, G. (1976). Education and female participation in the labour market. International Labour Review, 114(3), 281–297.

Statistics Korea. (2000). Annual report on the economically active population. Daejeon: Statistics Korea.

Statistics Korea. (2005). Social indicators. Daejeon: Statistics Korea.

Statistics Korea. (2012). Social Indicators. Daejeon: Statistics Korea.

Treiman, D. J. (1977). Occupational prestige in comparative perspective. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Treiman, D. J., & Terrell, K. (1975). Sex differences in the process of status attainment. American Sociological Review, 40(2), 174–200.

Tsai, Shu.-Ling. (1998). The transition from school to work in Taiwan. In Y. Shavit & W. Müller (Eds.), From school to work: A comparative study of educational qualifications and occupational destinations (pp. 443–470). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Yoo, H. J., & Kim, W. H. (2006). The occupational status scores in Korea: Past and present. Korean Journal of Sociology, 40(6), 153–186.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this paper was provided by Namseoul University. This study was developed based on Seong (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seong, M. Gender Comparison of the Effect of Education on Occupational Achievement in South Korea (1960s–1990s). Asia-Pacific Edu Res 23, 105–116 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0091-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0091-z